IN THE SUMMER of 1968, while Tony Blair was play-acting with a group called The Pseuds at Fettes College in Edinburgh (where he broke all the rules on drinking and smoking and his main interest lay in playing the guitar) and Bill Clinton was at Oxford University (where he famously “didn’t inhale, didn’t get drafted and didn’t get a degree”), Vladimir Putin took a walk down Leningrad’s Liteiny Street to the KGB offices, where he hoped his services would be enlisted.

His physique and confidence had been boosted by his prowess at judo and, like many of his generation, he was looking for a job in what were known as ‘the agencies’, the various arms of state security, membership of which represented a significant step up the Soviet career ladder. Putin already saw himself as a leader. As a member of the Komsomol, he was expected to give a lead to other pupils at Grammar School No. 281, a task he took to heart, handing out autographed pictures of himself inscribed with messages such as ‘A healthy mind in a healthy body’, and offering advice to other pupils about how they should conduct themselves.

He was a student who would speak about current affairs in weekly presentations to his class, grasping the lectern with both hands as he expounded his views. There was a lot for the young Soviet mind to take in. Khrushchev had been deposed in 1964 and the lugubrious old Ukrainian Leonid Brezhnev was at the Kremlin helm. He abandoned ‘Mr K’s’ liberal reforms, invested heavily in arms and invaded Afghanistan, ushering in a period known to Russians as zastoinoe vremya, the time of stagnation.

If some thought Putin big-headed and self-promoting, such opinions did not deter him. He developed a knack for telling improbable stories with a straight face and enjoyed it when he was believed. More importantly, he lost his desire to become a chemist when, in the flickering light of the October cinema on Moscow’s Novy Arbat Street, his life took a completely new direction.

Putin loved the cinema and his boyhood dream (or so he later confided to Hollywood film star, Jack Nicholson) was to become an actor. All that changed when he saw The Sword and the Shield (Schit i mech), a thriller about a Russian spy who infiltrated SS headquarters in Berlin and stole Hitler’s secrets. The following day he told his classmate Viktor Borisenko, ‘I am going to be a spy – they are the people who win wars, not armies. The soldiers are just servants, the brawn not the brains’. He was thrilled to learn that the KGB was known in Lenin’s day as ‘the sword and shield’ of the Revolution.

The most immediate effect of his sudden conversion was that he dropped physics and chemistry in favour of Russian literature and history, and continued with his German. ‘He was one of the rare students who had a very clear idea about his future,’ says Tamara Stelmashova, his social history teacher. ‘He was focused, determined, with a strong character, very serious, responsible and just.’ On a visit to his home, she noted that on one of the walls there was a picture of Felix Dzerzhinsky, the founder of the Bolshevik special services, the Cheka – forerunner of the KGB, now the FSB.

Volodya worked hard at his studies and spent weekends cramming for his school leaving exams at his parents’ three-room dacha at Tosno. Vera Brileva lived in the same street. She met Volodya in 1968, when she was 14 and he was 16. She became a frequent visitor to the Putins’ dacha and also to their home in Leningrad. In an interview with the Sobesednik newspaper, she portrayed the future president as a muscular student who feared no one and had a magnetic effect on women. When he arrived in Tosno, ‘girls just threw themselves at him,’ Vera said. ‘He had some kind of charm about him. To this day, I remember his hands – he had short, strong fingers.’

Vera recalls a New Year’s Eve party at the Putins’ dacha where somebody suggested playing Spin the Bottle. Volodya gave the bottle a spin and it pointed at Vera. He kissed her on the lips. ‘It was a brief kiss,’ she says, ‘but I felt so hot all of a sudden.’ She and Volodya started to see one another, although they were rarely alone: he would invite a group of friends to the dacha, and it was a rare party that did not include a rendition of his favourite song ‘The Dashing Troika This Way Comes’, which he performed with great gusto. The lyrics eulogise a bold young coachman who sings to the girl he has been forced to leave behind. His favourite Russian singers were Bulat Okudzhava and Vladimir Vysotsky.

One day an assertive young woman called Lyuda joined the group to hear the performance. After dinner, the boys asked her to wash the dishes but she refused, saying: ‘My husband will be the one to do the dishwashing for me’. At that point, Vera felt she would face no competition for Volodya’s affections from the new arrival. She knew that he was a shirker when it came to household chores: ‘And anyway, she was a brunette and I knew he preferred blondes’.

Vera also discovered that her beau preferred studying to romance. He declined invitations to accompany her to the cinema, saying he had no time for entertainment. ‘Despite his charming manner, he always wore a sombre expression on his face,’ she said. ‘Everybody would burst out laughing while Volodya just sat there, still and emotionless. And he would be amazed at some trifling matter. I would say to him “That’s the way it should be done,” and he would go, “Really? You must be kidding me!”’

Vera recalls that Volodya’s desk at home was positioned next to a sofa in the corner of the Putins’ room at the kommunalka in Baskov Lane. One day when she called he made it clear that he would prefer to be alone. As he sat writing at his desk, she tried to make conversation: ‘Volodya, do you remember the time when . . .’ Putin cut her short. ‘I remember only things I need to remember,’ he snapped. Vera was heartbroken. A proud girl, she felt her feelings for him dissolve at that moment. She walked out and never went back. ‘What can I do with a man who treats me this way?’ she asked her friends.

Now a married pensioner, Vera says, ‘Even to this day, they suggest I write to him to let him know I am still around, but I’m a full-blooded Russian and he knows it. I wouldn’t write and ask for help even if I was starving and living under a bridge. Why would he think of me now, when he didn’t think of me then?’

THE REASON FOR PUTIN’S preoccupation with study was that he had taken a short walk north of his home along Liteiny Street to the building Leningraders referred to as the Bolshoi Dom, ‘The Big House’, the ugly nine-storey Leningrad headquarters of the KGB. It turned out to be a practice run and so did the next one. It was not until his third attempt that he plucked up the courage to ask a staff officer, ‘How can I become a KGB agent?’

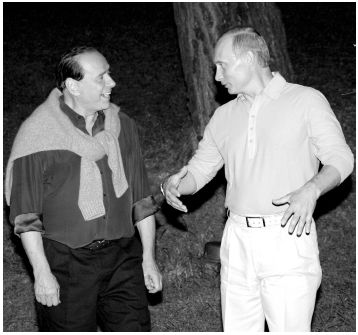

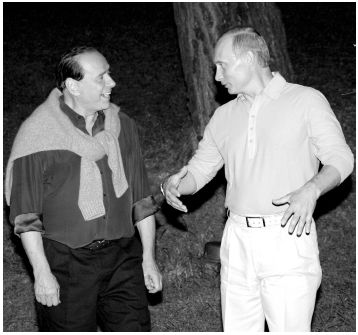

THEY WERE both prime ministers when this holiday snap was taken: Vladimir Putin with his friend, Italy’s then-leader Silvio Berlusconi.

He was not disappointed. Though used to dealing with cranks and juvenile dreamers, the officer spoke patiently to the thin, pale-faced 16-year-old and advised him to get a university degree. Putin later recalled that the man also said, ‘We don’t take people who come to us on their own initiative’. Even so, he was determined to get to university, despite the fact that there were 40 applicants for each of the small number of places and his parents doubted that he was sufficiently academic to get one. Exceeding all expectations, however, Vladimir was admitted to the Faculty of Law at Leningrad State University (LGU) in 1970, to read International Law.

At university, he studied hard and practised his judo. He was involved in numerous tough contests, which he remembers as ‘a form of torture’. Anatoly Rakhlin says he was the type of fighter who preferred training: ‘Very calm, cold-blooded and clever’. He adds: ‘As a fighter he feared no one – he would fight 100kg men. He was very good at changing his grip. It was difficult to guess where he would throw you. His favourite moves were the leg sweep and the shoulder throw.’

In the Leningrad championships, Putin faced the world champion, Volodya Kullenin. He thought he had won when he succeeded in throwing his opponent across his back in the first few minutes, but the referee allowed the fight to continue – the crowd would never tolerate the world champion being beaten so easily. The bout ended when Kullenin twisted Putin’s elbow and the referee judged him to have grunted. Since any sort of crying out was construed as signalling defeat, Kullenin was declared the winner. Putin thinks he should have won but adds: ‘I’m not ashamed to lose to a world champion’.

After attending a training camp on Khippiyarvi Lake, he travelled to matches at various venues across the Soviet Union, once to Moldavia to prepare for the Spartakiad competition, which was open to all-comers from the USSR. He was devastated in 1973 when his close friend Volodya Cheryomushkin, who had taken up the sport at his insistence, broke his neck diving head-first into the mat during a bout. Paralysed, Cheryomushkin died 10 days later in hospital. Putin, who supposedly lacked the ability to express his emotions, kept himself in check during the funeral but later broke down and wept at the graveside with Volodya’s mother and sister.

Thanks to the camaraderie of sport, Putin’s reclusive streak became less noticeable. He joined in holiday activities with other students, swimming at a Black Sea resort and cutting down trees in northern Russia (which earned him the very decent sum of 1,000 roubles for six weeks’ work). And there were other advantages. Instead of spending years as a conscript in the Russian Army, he took part in exercises run by the Institute for Military Affairs, ending up with the nominal rank of lieutenant. From an uncertain, troubled childhood he was emerging as a young man with prospects. He had learned to balance friendships and focus on his long-term aim of becoming a national hero. He was a hardworking and conscientious student, if not a particularly gifted one.

His 21st birthday came and went and he was concerned that he had still not heard from the very people he was trying to impress, the KGB. His spirits picked up when Maria won a Zaporozhets-966, a little rearengine car made in the Ukraine, after she had been given a 30-kopeck lottery ticket instead of change at a cafeteria. She could have taken the value of the vehicle – 3,500 roubles – in cash, which would have alleviated the family’s poverty for some considerable time, but instead she gave the car to her son.

Putin describes himself as ‘a pretty wild driver’. He once hit a pedestrian who jumped in front of his car, apparently with the intention of committing suicide. The man must have been injured but was able to get up and run away. The story got around that Putin had jumped out of his car and chased after him. The allegation brought a furious response: ‘What? You think I hit a guy with my car and then tried to chase him down? I’m not a beast.’

In his fourth year of university, a stranger approached him. ‘I need to talk to you about your cover assignment,’ he said. ‘I wouldn’t like to specify exactly what it is yet.’ Putin knew this was the moment he had been waiting for. He agreed to meet the man in the faculty vestibule but the man was late. Putin waited 20 minutes. Thinking he had been the victim of a practical joke, he was about to walk away when the man arrived, out of breath. ‘It’s all arranged,’ he said, ‘Volodya, how would you feel if you were invited to work in the agencies?’ Without a second’s thought, Putin replied in the affirmative. Had he left even moments earlier, the history of present-day Russia would have to be rewritten.

As explained to him, the KGB deal was that after graduation he would be accepted as a trainee agent with good opportunities for promotion. In contravention of the secrecy he had been instructed to observe, he told his father that he was joining the KGB. His friends were simply informed that he had ‘secured a job in the police force’, but since his ambition to join the secret service was pretty much an open secret, few were left in any doubt what ‘the job’ entailed.

Putin graduated as a lawyer in 1974, and the following year attended School No. 401 near the Okhta River, where he was trained in counterintelligence measures. His friends recall the ‘supreme happiness’ that lit up his face in those early days, but not everybody was prepared to accept his claim that he worked for the police. One of his closest friends, Sergey Roldugin, a soloist in the Mariinsky Theatre Symphony Orchestra, confronted him about it. ‘I’m a cellist,’ he said. ‘I know you are a spy – I don’t know what that means. Who are you? What do you do?’ Putin coolly replied: ‘I’m a specialist in human relations’.

It was a description that was actually not too wide of the mark: a KGB officer’s work was largely about letting go of self and immersing oneself in the other fellow in order to obtain information. To study human weakness, he started examining those around him. One man admits to becoming quite paranoid about Putin constantly questioning him while staring into his eyes. An instructor’s report at the end of his first six months shows that Putin had to be told repeatedly that his probing should be far more subtle if it was going to yield results.

Probably the most valuable lesson he learned about the KGB’s attitude towards ordinary people was when some of his older colleagues were creating a hypothetical case for the benefit of trainees. When one veteran agent instructing his class at school 401 suggested that a certain course of action should be taken, Putin interrupted him. ‘You can’t do that,’ he said. ‘It’s against the law.’ His KGB colleagues looked at him aghast. ‘Our instructions,’ one patiently explained, ‘are the law.’ The following year Putin started work in the KGB’s counter-intelligence department at the Big House on Liteiny Street.

Meanwhile, Putin continued with his judo training. Volodya Kullenin had taken to drink and dropped out of the sport. Putin was sorry to see his decline but in 1976 he replaced Kullenin as judo champion of Leningrad. Kullenin later died of alcoholism, but alcohol was never a serious problem for Putin, despite rumours to the contrary. He recalls getting drunk as a student ‘chasing shish kebabs down with port wine’, while Vera Brileva says he drank dry wine and champagne with his friends but adds: ‘He preferred milk’. Anatoly Rakhlin maintains his desire to win at judo was so strong that he was always sober. And Klaus Zuchold, an East German spy who knew him for almost five years in the 1980s, relates: ‘Whenever we drank together, he always made sure he was at least three glasses behind everyone else’. There was even one report that he was seen watering a pot plant with his glass of vodka.

At the Big House, he was talent-spotted by a KGB intelligence officer and sent to Moscow for a year to be trained in foreign intelligence. ‘Of course I wanted to go into foreign intelligence,’ he says. ‘Everyone did. We all knew what it meant to be able to travel abroad.’ When he returned to Leningrad, his friends noted that he no longer brimmed with boyish excitement about whatever work it was that he did. He seemed colder and more detached. He moved in a different circle, conversing with academics and foreign businessmen – people who could provide him with the very oxygen he needed: information. Speaking fluent German and passable French and English, he was chosen to show foreign visitors around the city and, for the first time, travelled abroad with Soviet groups to keep foreign agents at bay.

In his memoirs, Putin says his work involved ‘dealing with people’ but it isn’t known how successful he was at recruiting genuine informers. He also admits he disliked the way the KGB was employed to crush dissident art and harass artists. Rather clumsily, he says today: ‘The co-operation of normal citizens was an important tool for the state’s viable activity’. In other words, Leningraders were encouraged to keep an eye out for unusual behaviour. Interestingly – though under very different circumstances, clearly – U.S. citizens today are encouraged to keep a watchful eye on behalf of state authorities. Walmart runs an ‘if you see something, say something’ Homeland Security campaign and a recently launched iPhone application, PatriotApp, urges citizens to report similar information to the FBI and other federal agencies.

BACK INTO PUTIN’S life in the summer of 1979 came Lyuda, the girl who had refused to do the washing-up at his family’s dacha and who was now a medical student. His parents were pleasantly surprised to learn that he had met up with Lyuda again and was seeing her on a regular basis, especially when – eventually – he brought her home to meet them.

Lyuda took care of him in much the same way as she had always done, telling him what to eat and what to wear, impressing on him the importance of looking smart. She even polished his shoes – no mean feat for a girl who had once refused to wash the dinner plates. Even today, Putin can’t say whether he was in love with her or not. She was a trifle bossy, but he decided that quality was desirable in a wife. It was her way of getting things done, and a wife had to get things done if she was going to serve her man.

So he proposed marriage. In her practical, matter-of-fact way, Lyuda accepted and started to plan the wedding. Her parents bought a wedding dress and his parents invested in a new suit for him, along with the necessary rings. The bridegroom visited Leningrad Town Hall to apply for a marriage licence.

No one quite understood why Volodya never actually married Lyuda. Everyone thought they were well-suited and would have had wonderful children. His mother adored her and years later had the nerve to tell the woman he did marry that she would rather have had his first love as a daughter-in-law. But whether it was last-minute nerves or just the fact that he couldn’t accept becoming one half of a couple, he called off the wedding, telling the bride-to-be that he was ashamed of himself for not having ‘thought it through before it got this far’. ‘That was one of the most difficult decisions of my life. It was very hard. I looked like a total jerk. But still I decided it was better to break up now than for both of us to suffer for the rest of our lives. I didn’t run away, of course, I told her the truth and that’s all I thought I had to do.’ His friends were shocked. One of them explains: ‘The trouble with Volodya was that he could never express his feelings and from what I’ve seen of him on television he still can’t. He thinks the truth but wraps it up in a myth – that’s why he was so well suited to the KGB.’

AS ONE of his chauffeurs testifies, he loves to drive fast cars, but has to let others do the job when he’s on official business. The same does not apply when he’s on the piste: here he rides a high-speed snowmobile

PUTIN’S NEXT LOVE interest was a young woman with shoulderlength blonde hair – a prerequisite according to Vera Brileva – and big blue eyes. He was thin, short and clearly paid little thought to the style or quality of his clothes – not, as Lyudmila Alexandrovna Shkrebneva was later to admit, the sort of man she would have favoured with a second glance on the street. But it was too late now: she had agreed to go on a blind date with him. The main attraction was that Vladimir Putin had tickets to see Arkady Raikin, one of the funniest comedians of his day, at the glamorous Lensoviet Theatre – they didn’t have anything like that in her home city of Kaliningrad (the former East Prussian city of Königsberg).

Lyudmila had been born in that dull, militarised Baltic Sea enclave on 6 January 1958. Dropping out of technical college in her third year, she joined Aeroflot as a flight attendant in order to get away. Unlike another flight attendant, Irina Malandina, who went on to marry Vladimir’s sometime friend Roman Abramovich, the 22-year-old had no well-connected relative to wangle her a job with an international airline where she could meet better marital prospects.

Lyudmila was on a three-day stopover in Leningrad with another flight attendant when she agreed to make up a foursome. The date was 7 March 1980. The two girls and her friend’s current boyfriend met on Nevsky Prospect near the ticket office. Volodya, who had a reputation for always being late, was already standing on the steps. He was poorly dressed – his one good coat was now threadbare – and Lyudmila thought he looked unprepossessing. Interestingly, Putin was to maintain years later that they met when he found himself sitting next to her in the theatre – he did not like to admit that his wife had been a date arranged for him by a mutual acquaintance and that he had secured tickets for both of them without ever having set eyes on her.

The comedy of Arkady Raikin was in total contrast to the quiet, introverted man at her side, but there was something about the young Volodya that made Lyudmila agree to see him again the very next night. And the next. He seemed to be able to get tickets for almost everything.

On the second night, it was the Leningrad Music Hall and on the third, the Lensoviet Theatre again. It was a promising start, although never in her wildest dreams could she have imagined that Volodya would one day make her Russia’s First Lady.

On those first dates, Putin told his new friend that he worked in the criminal investigation department of the Leningrad police force. He says: ‘I told her I was a cop. Security officers, particularly intelligence officers, were under official cover’. Lyudmila recalls she had no qualms about going out with a policeman and was keen to keep in touch. When Putin asked for her telephone number, she told him she had no phone at home but could call him, so he wrote down his number as they were thundering along on the Metro. Lyudmila then returned to Kaliningrad, where she told friends she had met an interesting man, albeit a ‘plain and unremarkable one’. It was too soon to talk of love, but she was greatly intrigued. Determined to keep in touch, she called him almost every day from work or a public phone booth.

When friends inquired what her new boyfriend did for a living, Lyudmila told them what Putin had told her: that he was something to do with the police. She discovered the truth after she had given up her job and moved to Leningrad to be near him: ‘After three or four months I had already decided he was the man I needed’. Asked why she had reached such a momentous conclusion about the man she had described to her friends as ‘plain and unremarkable’, she says: ‘Perhaps it’s that inner strength which attracts everybody [to him] now.’

SINCE EVERYONE in the city seemed to know what they did at the Big House on Liteiny Street, it didn’t take her long to determine her sweetheart’s true profession. By then, however, she was besotted and as she had no experience of the security forces herself, she thought little of it.

Telling her that ‘everyone of our age should do something to improve themselves and broaden their minds’, Vladimir persuaded his girlfriend to enrol at Leningrad University. Since he was keen on languages, she chose French and Spanish. Almost as an afterthought, he suggested she also take a typing course – it might be helpful to him in his work – and she agreed. He also encouraged her to study the social graces acquired by some of the wives of his colleagues.

One character trait she found unattractive was his fierce temper if he thought someone was flirting with her – or, indeed, if he considered her own behaviour to be flirtatious. This was one jealous man. As he deemed right and proper, they lived separately, he in a corner of his parents’ room at their communal apartment and she in student quarters. It was hardly a passionate start to the romance, but then Putin was not known to be a passionate man. Friends say they consummated their affair only when Vladimir took her on holiday to the Black Sea resort of Sochi.

By then Lyudmila knew she was in love. She was anxious to put their relationship on a permanent footing, but the more hints she dropped, the further he seemed to withdraw from the prospect of marriage. He was, he later admitted, an expert at planning his every move and that applied to romance as well as his career. It was three and a half years before he finally raised the question of their relationship. Putin says his friends had started telling him he should get married, but it is intriguing to note that his decision coincided with a dramatic change in Russian life. Brezhnev had died in November 1982 and Putin’s hero Yuri Andropov, head of the KGB, was in the Kremlin. Andropov tackled the economic stagnation and unchecked corruption of the Brezhnev era, but also cracked down ruthlessly on any kind of dissent, all actions that were likely to generate a mood of optimism in devoted young KGB officers like Putin.

How does a man like Putin propose? Clumsily, it turns out. Lyudmila recalls the moment: ‘One evening we were at his place and he said: “My dear, now you know everything about me. All in all, I’m not an easy person to be with.” And then he described himself as a silent type, sometimes rather abrupt, who might occasionally say offensive things. In other words, a risky life partner. Then he asked: “You must have decided something for yourself in the three and a half years [we have been together]?” All I understood was that we were apparently going to break up. “As a matter of fact I have,” I said. He asked me doubtfully: “Really?” At that point I realised we were definitely breaking up. “Well, if so, I love you and propose we get married on such-and-such a date,” he said. This came totally out of the blue. I accepted and we agreed to get married three months later. Marriage was not an easy step for me. Nor was it for him,’ she concluded, before adding the cryptic remark: ‘Because there are people who take a responsible attitude to marriage’.

Other biographers have recorded the date of their wedding as 28 July 1983, when the bridegroom was in his thirty-first year, though I have been unable to find any records which substantiate these claims. However, these were Soviet times, when official ceremonies took place in registry offices rather than in church and records are not always easily obtained.

Whatever form the union took there can be no doubt about the celebrations. There were two receptions – one for family and close friends at a floating restaurant on the Neva River, and another the following day at the Hotel Moscow, which was exclusively for his KGB colleagues, who had no wish to reveal their identities to strangers. For the honeymoon they returned to the location of their first intimate encounter, Sochi, and Lyudmila later surprised their friends by confiding that her husband had made it ‘as romantic as romantic could be’.

The newlyweds went to live with his parents who, mercifully, had moved into a two-bedroom apartment on Stachek Prospect in Avtovo, a district of newly constructed apartment blocks in the south of the city. The kitchen windows were so high up that, sitting at the kitchen table, the only view was ‘the wall in front of your eyes’. Vladimir Spiridonovich had been given the flat as a disabled war veteran when he retired from the factory in 1977. The newlyweds’ room was 20 metres square, little more than half the size of the one in which he had grown up, and the insulation of the walls in the cheaply-built block afforded them little privacy. By Soviet standards of the time, however, they were relatively well off. Vladimir still had the Zaporozhets and he enjoyed driving around the city with his new wife at his side. He has always loved to drive and one of the presidential chauffeurs was later to say: ‘He would like to take the wheel of the limousine when we are travelling at high speed in the motorcade to his dacha or to the airport, but he knows he does not have the necessary training for terrorist avoidance that we have. It frustrates him though.’

PUTIN and his wife Lyudmila accompany Lyudmila Narusova (second right), the widow of St Petersburg’s first Mayor, Anatoly Sobchak, and her daughter Ksenia, to lay flowers on the grave of Putin’s mentor in the city’s Nikolskoye cemetery.

Lyudmila discovered early in their marriage that her husband had other faults apart from his temper. Describing him in an unguarded moment as a ‘bona fide male chauvinist’, she complained that he expected her to do everything around the home (while this might raise eyebrows abroad, where such behaviour would be considered ‘old school’, in Russia it remains the norm and is perfectly acceptable). He also told his friend that for a man to praise his wife was to spoil her. ‘He has put me to the test throughout our life together,’ she was to tell Putin’s biographer, Oleg Blotski. ‘I constantly feel he is watching me and checking that I make the right decisions.’ And giving an unequivocal indication of what was to cause her considerable stress later in their marriage, she added: ‘He is extremely difficult to cook for and will refuse to eat a dish if he does not like the slightest ingredient. He never praises me and that has totally put me off cooking.’

But these were the honeymoon days and she was already expecting their first child when he was sent to Moscow for further training at the Yuri Andropov Red Banner Institute in September 1984. Lyudmila moved into a bedsitter on the northern side of Leningrad and carried on with her studies. At Red Banner students were given a nom de guerre beginning with the same letter as their surname. Thus Comrade Putin became Comrade Platov. The course included tests for physical endurance and clear thinking. There were night parachute jumps, lessons in how to lose a tail and how to arrange for coded information to be left at dead-letter drops.

Lyudmila visited him once a month and he came home a couple of times. On one of those trips he managed to break his arm. ‘Some punk was bugging him in the Metro and he socked the guy,’ his close friend Sergei Roldugin says. ‘He was very concerned that those who taught and trained him might hold it against him.’

The Putins’ first child, Maria, named after Vladimir’s mother and known as Masha, was born on 28 April 1985, while her father was on leave. Sergei Roldugin picked up mother and baby from the maternity hospital and, with Putin and his own wife Irina on board, drove to his father-in-law’s dacha at Vyborg, where they celebrated the baby’s birth.

Putin graduated from the Red Banner Institute in July 1985. While his ‘analytical turn of mind’ was highly regarded, he received a negative character assessment for being withdrawn and uncommunicative, and for having what was described as ‘a lowered sense of danger’. This last characteristic was considered a serious flaw. Agents had to be pumped up in critical situations in order to react well and an inability to feel fear inhibited the flow of adrenalin. ‘I had to work on my sense of danger for a long time,’ he says.

Now in his early thirties, he was a trained foreign operative and yearned to work outside the USSR against his country’s enemies. He devoured information from older KGB colleagues who returned from abroad, not the die-hard Stalinist variety, but those who had experienced a different way of life. ‘They were,’ he noted, ‘a generation with entirely different views, values and sentiments.’

At one point he grilled one of his friends who had worked in Afghanistan about the Soviet occupation, a popular cause in Russia. Putin wanted to know if it was true that his signature was required for missile launchings against Afghan targets. The man’s reply stunned him: ‘I judge the results of my work by the number of documents that I did not sign’.

These were stirring times. Mikhail Gorbachev had been elected General Secretary of the Communist Party on 11 March 1985, just three hours after the sudden death of Konstantin Chernenko. Almost immediately he introduced perestroika (the controversial restructuring programme) to revive the stagnant Soviet economy, and within a matter of months perestroika had been joined by glasnost (openness of speech), demokratizatsiya (democratisation) and uskoreniye (acceleration of economic development).

Putin’s chance to see things clearly for himself came when he was assigned by a KGB commission to East Germany. It had been clear to him since his early days at Red Banner that he was being prepared for a German posting, because they pushed him to continue his language studies. It was just a question of whether it would be the German Democratic Republic (GDR) or the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG). To make it into the latter, the candidate had to work at Moscow Centre for up to two years. Putin says he decided it was better to travel right away and so, now a fully-fledged KGB man, he accepted the posting without complaint, packed his bags and kissed Lyudmila goodbye.