BY THE TIME Vladimir Putin started work in the presidential administration building at No. 4 Old Square in the autumn of 1996, Moscow’s brave new world was being assailed by warring politicians, mafia-style gangsters, black marketeers and the new breed of super-rich tycoon, the oligarchs, who – as we have seen – had risen to the starry heights through perestroika and the mendicant state of Boris Yeltsin’s presidency.

Putin was in charge of the legal division of the directorate of presidential affairs, whose task was to defend the Kremlin’s ownership of important buildings against the sticky fingers of other ministries, and to manage Russia’s huge portfolio of overseas properties, numbering some 715 sites in 78 countries. The directorate published no accounts and was not answerable to parliament, despite the fact that its assets were worth billions of dollars and its annual revenue from hotels, airlines and car fleets at this time amounted to $2.5 billion.

Putin’s boss Pavel Borodin had been discovered by Yeltsin in the remote Siberian city of Yakutsk, where he was the mayor. Recognising a kindred spirit (and potential drinking partner), he brought him to Moscow in 1993. Dressed in well-cut suits, with cufflinks, watch and pen, and handing out engraved, gold-rimmed business cards, Borodin lived extremely well on his official salary of $1,000 a month plus perks. To keep in touch with his empire, there was a bank of nine telephones, including hotlines to the president, prime minister and the security services on a special desk in his office, with a further dozen phones in an anteroom.

The directorate was also involved in the renovation and restoration of a couple of Kremlin buildings, including the Great Kremlin Palace, a project that would take a hefty $488 million chunk out of the national budget and would subsequently link Borodin to allegations that the Kremlin’s property empire was being used as a slush fund.

‘Putin worked for me for nine months during which he travelled widely,’ Borodin explains. ‘He proved himself a really good worker. I am not saying this because of the lofty positions he went on to reach, but because I liked and admired him a lot then and still do. You can see how highly professional he is in the way he conducts international relations.’

Putin’s rise to the top was defined as much by hard work as by opportunity. Popular legend has it that he was a nobody who emerged from the shadows to become prime minister; in fact, he was a well-travelled lawyer who spoke three languages and was used to dealing with politicians as a senior member of the apparat (the country’s top bureaucracy). On 26 March 1997 he was promoted to Alexei Kudrin’s old post as head of the main control directorate (GKU), with a brief to audit the state agencies where kickbacks of one kind or another were an accepted custom.

Putin’s work inevitably brought him into contact with Boris Yeltsin and members of the Family. He barely needed his legal training to recognise the prevailing air of corruption that hung over the Kremlin, or to notice that among those who had the President’s ear were Boris Berezovsky and his sidekick Roman Abramovich. Indeed, Berezovsky had replaced Alexander Korzhakov as Yeltsin’s chief courtier. But the person whose judgment mattered most was undoubtedly his daughter Tatyana. ‘A grimace of dislike on her face was enough to get someone fired,’ Lilia Shevtsova writes in Putin’s Russia, ‘while an approving smile could speed someone else up the ladder of success.’

There were encouraging signs that the president might serve his full second term. His health had improved markedly following multiple bypass surgery at the Moscow Cardiological Centre the previous November to circumvent five clogged arteries supplying blood to his heart. During the seven-hour operation, he had transferred his formal powers to Prime Minister Chernomyrdin, including the black attaché case carrying codes to activate nuclear weapons. After coming out of the anaesthetic, he had quickly reclaimed them. Berezovsky and Abramovich knew that Yeltsin had to find a successor before he stepped down in 2000, someone who would be acceptable to Parliament, yet pose no threat to himself. It would be very much in their long-term interests if they could suggest the successful candidate.

In his new role at the GKU Putin set up an analytical group which uncovered misconduct by many state officials. Putin also prepared a report on the mismanagement of Borodin’s directorate, which almost precipitated another heart attack when Yeltsin read it. His report was quietly shelved. Yeltsin did not like washing dirty linen in public.

With unconscious irony, Yeltsin later commented that Putin’s reports while he was with the GKU were ‘a model of clarity’. He was also impressed by his businesslike manner and ‘lightning reactions’ to interjections. ‘Putin tried to exclude any sort of personal element from our contact,’ he wrote in Midnight Diaries (which was compiled from notes made during his second term of office while suffering from insomnia). ‘And precisely because of that, I wanted to talk to him more.’

Putin’s art of detachment served him well in his work. At home, he was much more open about his feelings and he made no secret of his pride in his two beautiful daughters. His relationship with his wife was turbulent at times and Lyudmila wasn’t afraid to speak out about their differences. In a rare move of independence she spent four days in Hamburg with Irene Pietsch, the friend she had met in 1995 when Vladimir was on an official visit to St Petersburg’s sister city. Pietsch recalls that Lyudmila was angry with her husband for refusing her permission to use a credit card. ‘That’s silly. I will never be like Raisa Gorbacheva,’ said the future First Lady.

The two women developed a close friendship and Lyudmila shared intimate secrets in a series of personal emails and letters – never suspecting that Pietsch would one day profit from their publication. According to Pietsch, Lyudmila said the reason Vladimir was the right man for her was because he didn’t drink or beat her up. But it has been pointed out on Lyudmila’s behalf that she was merely quoting a Russian saying that a good man doesn’t do such things – not singling out her husband for such narrow attributes. Pietsch also made much of Lyudmila’s apparent interest in astrology, saying that Putin bracketed it with occultism and paganism ‘and shushed her whenever she started talking about the zodiac’. This gave a distorted view to the mild interest Mrs Putin – a strict Orthodox Christian – has in, say, reading her horoscope in the daily newspaper.

AGAIN ACCORDING TO Pietsch, Lyudmila admitted in her correspondence that she found some of her husband’s habits annoying. ‘He spends too much time with his friends in the evenings,’ she is said to have written, ‘and when he brings them home I have to serve them drinks with gherkins and fish.’ Bizarrely, she also revealed that her husband ‘always goes to Finland when he has something important to say – he doesn’t think there is anywhere in Russia where you can speak without being overheard’.

On another occasion Pietsch says Lyudmila confided in her: ‘It will happen that I try very hard and do something particularly well and Volodya praises me for it, but then I’m certain to be at fault some time later and my good deeds don’t count any more and I can be rehabilitated only by working on my mistakes. That hurts me.’

Pietsch also claims that when she spent a week with the Putin family at their dacha at Arkhangelskoe in 1997 – during which time Lyudmila played the good wife, cooking home-made soup in the kitchen while Vladimir, clad in pants and a pullover, was a charming host – Lyudmila joked to her guest: ‘Unfortunately, he’s a vampire’.

Clearly never intending to be invited back into the Putin home, Pietsch publicly describes the Prime Minister’s blue-green eyes as ‘two hungry, lurking predators’. Although he probably loathed his indiscreet guest, Putin accepted Pietsch as his wife’s friend and contented himself with a little leg-pulling, telling her with a straight face that she would deserve a monument if she could put up with his wife for three weeks.

Pietsch’s disclosures brought unwanted media attention to Mrs Putin. But when he was subsequently asked by a journalist about his wife’s indiscretions, he replied: ‘The citizens of Russia elected me, not my wife, as the president. I am very grateful to her; she has a difficult cross to bear.’

BACK IN ST. PETERSBURG the campaign against Putin’s friend and political mentor Anatoly Sobchak had intensified. ‘At that time there was a conflict between two major groups in the Kremlin,’ says Galina Starovoitova’s aide Ruslan Linkov, a member of the local Democratic Russia party. ‘Korzhakov and Soskovets were on one side, and Chubais was on the other. Both of them were fighting for access to Yeltsin, and St Petersburg appeared to be a part of the fight.’

Korzhakov might have been sacked as Yeltsin’s security chief, but he continued to wield power in the Interior Ministry and through his friends in the FSB. He also held sway over the prosecutor-general, Yuri Skuratov, which allowed him to continue his vendetta against his political rival. ‘They wanted to get a lot of kompromat [compromising material] on Sobchak,’ Yeltsin writes in Midnight Diaries, ‘to drag him into a serious corruption case.’

According to Yeltsin the two conspirators pursued Sobchak with further allegations of corruption, while Sobchak accused Korzhakov of fabricating evidence against him. In an interview with the St Petersburg Times, he said his phones were being tapped and that he was being tailed – a fact later confirmed by Yeltsin in his memoirs. Then, during an interrogation in November 1997, Sobchak was taken ill, apparently having suffered a heart attack. On 7 November he was smuggled out of the country in a private charter plane to Finland and from there to France, supposedly to seek medical treatment.

Until his death in 2007 Yeltsin maintained that Putin had facilitated the escape of his great friend and mentor, which cost some $10,000. ‘When I learned what Putin had done, I felt great respect and gratitude towards him,’ he wrote. Putin has always denied having anything to do with Sobchak’s escape and claims the former mayor went through the normal customs and passport procedures at the border like any other law-abiding citizen. ‘They hounded the poor guy all over Europe,’ he says. ‘I was absolutely convinced that he was a decent person – 100 per cent decent – because I had dealt with him for many years. He is a decent man with a flawless reputation.’

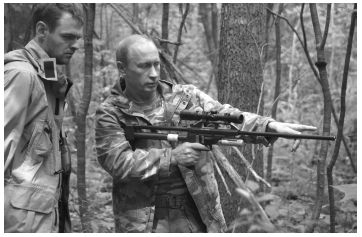

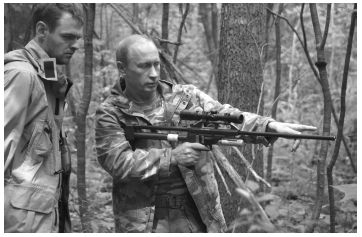

WHILE BEING shown around the Ussuri Game Reserve in Russia’s Far East corner by Moscow Zoo’s chief vet, Mikhail Shenetsky, Putin went in search of Siberian tigers, but his gun fired only tranquiliser darts.

Putin stayed with the GKU for a little over a year and was relieved when, on 25 May 1998, he received another promotion – this time to First Deputy Chief of Presidential Staff, responsible for relations with the regions. The move came just in time: while he recognised that his work at the GKU was important, Putin found it uninteresting and had toyed with the idea of resigning in order to open his own legal practice. His new boss was Yelstin’s favoured son, Valentin Yumashev, who was chairman of the Presidential Executive Office.

In his new role Putin chaired a commission drafting treaties on the division of responsibilities between central government and the 89 constituent parts of the federation. In conversations with regional governors, he developed his idea of creating a ‘new federalism’ after learning that the vertical chain of government had been destroyed during the break-up of the old Soviet system and that it would need to be restored in some new way if Russia was to be governed effectively.

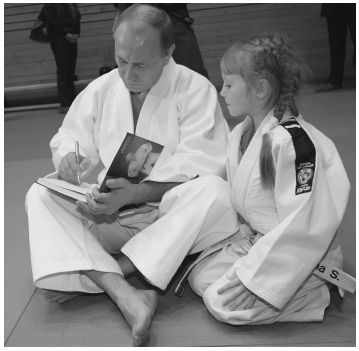

PUTIN conducted a judo session at the Top Athletic School during a visit to St Petersburg in December 2010, and found time to sign an autograph for a young admirer.

Putin had been in that ‘most interesting’ job for just three months when he received the biggest shock of his life. On 25 July 1998 he was asked to meet the new prime minister, Sergei Kiriyenko, at the airport. Kiriyenko, who had replaced Chernomyrdin in March, was returning from a visit to see Yeltsin, who was holidaying in the Karelia region on the Gulf of Finland. At the airport Kiriyenko, a self-assured 37-year-old, greeted him with the words ‘Hi, Volodya! Congratulations!’ Putin was taken aback. ‘What for?’ he asked. ‘You have been appointed Director of the FSB.’

Putin had been given no hint that he was even being considered for this forbidding office. ‘The President simply signed a decree,’ he says. ‘I can’t say that I was overjoyed. I didn’t want to step into the same river twice.’ He was now 46 years old and had set his heart on a career in regional reform. He rang Lyudmila, who was on holiday at a resort on the Baltic Sea. Conscious that such calls were monitored or could be intercepted, he told her that he had ‘returned to the place where I began’. Lyudmila thought he was saying he had been demoted to being Borodin’s deputy once more, but when she finally got the point she was devastated. It meant re-entering ‘the closed life’ which they had abandoned in St Petersburg after returning from Dresden.

The first thing that had to go was her friendship with Irene Pietsch (an act which Pietsch repaid by betraying her confidences). According to Pietsch, Lyudmila complained in a final telephone call to her: ‘It’s terrible; we won’t be allowed to contact each other again. This awful isolation – no more travelling wherever we want to go, no longer able to say whatever we want. I had only just begun to live.’

Yeltsin recalls in Midnight Diaries that he had offered Putin the rank of general, but Putin insisted he return to his old agency as a civilian, just as his hero Yuri Andropov had done when he took over the KGB in 1967. Yeltsin claims to have noticed Putin in 1997 and, once again, it was Putin’s eyes that had made such an impression: ‘Putin has very interesting eyes,’ he says. ‘They seem to say more than his words.’ He goes on to praise Putin’s intelligence and democratic instincts, his good ideas and impressive military bearing. Yeltsin ‘had the feeling that this man, young by my standards, was absolutely ready for everything in life, and could respond to any challenge clearly and distinctly’.

More important than Yeltsin’s feelings was the fact that Tatyana had been impressed by the cool way Putin got on with his work while offering no opinions about what was going on around him. The power of Tanya-Valya had become an established fact of life in the Kremlin, while their antics outside the red-brick walls were a national scandal. They drove around Moscow in armoured Mercedes, surrounded by bodyguards and fawned over by flunkeys. Yeltsin’s loyal old guard were replaced by Tatyana’s nominees; these guys took over government institutions and were handed huge chunks of state property. Anyone perceived to be an opponent could find themselves out in the cold.

The inner circle consisted of Valentin Yumashev, Alexander Voloshin, Boris Berezovsky and Roman Abramovich, with three politicians, Victor Aksenenko, Viktor Kalyuzhny, and Vladimir Rushailo in the outer circle. It was noticeable that Abramovich had become indispensable as the Family’s treasurer. He had even displaced his mentor Berezovsky in Tatyana’s affections. Berezovsky had political ambitions and saw himself as a kingmaker. He talked too much, whereas Abramovich said nothing.

Yeltsin’s biggest headache was that the Russian economy had been hit by another financial tsunami following a sudden plunge in world oil prices to just $8.50 a barrel. The crisis had begun on 27 May 1998 – Black Tuesday – when share prices plummeted more than 14 per cent, bringing the stock market slide to 40 per cent since the start of the month. Interest rates, which had fallen from 42 per cent in January to 30 per cent, were suddenly raised to 150 per cent. The government owed more than $140 billion in hard currency and $60 billion in domestically traded rouble debts, short-term state bonds.

Yeltsin summoned Anatoly Chubais (who, in a typically eccentric move, he had sacked from the Cabinet just two months earlier) to the Kremlin and asked him to go, cap in hand, to Washington. Chubais returned with a promise of financial help from President Clinton ‘to promote stability, structural reforms and growth in Russia’. No one, however, had any confidence in Kiriyenko’s ability to manage the situation and it was the oligarchs who imposed Chubais – against Yeltsin’s wishes – as the head of the government’s team in crucial talks with the IMF. The $10 billion the international bankers were offering was not enough; Russia needed $35 billion.

On his next visit to the United States Chubais was successful in persuading the IMF to raise its loan to $22.6 billion over two years. Before the end of July a down-payment of $4.8 billion had secured matters until October at least – or so they thought. Unfortunately, foreign investors decided this was the moment to get out and they withdrew so much money that by the end of August the Russian banks were not so much squeezed as crushed.

There were too many variables in the Russian economy and one of the most unpredictable was the 65-year-old President’s health. With striking miners camping out in the city and people going hungry, Moscow Mayor Luzhkov threw down the gauntlet with a statement that if Yeltsin ‘cannot work and fulfil his duties, then it is necessary to find the will and courage to say so’. The attack was acutely wounding – Yeltsin had hand-picked Luzhkov for political advancement during perestroika and they had campaigned together as recently as 1996.

As he walked into the notorious grey-stone and yellow-brick Lubyanka building that housed the FSB headquarters, Putin says he felt as though he had been plugged into an electric socket. One of his main priorities would be to inflict a series of cost-cutting measures on the service, and that would mean making enemies. He reported to the outgoing director Nikolai Kovalev, who opened his safe with the words: ‘Here’s my secret notebook. And here’s my ammunition’. Kovalev had been keen to root out corruption in banks and businesses, but had failed to see that such corruption percolated right to the top of the Kremlin. Putin’s natural inclination might have been to carry on Kovalev’s work, but he knew he had been given the job (and with it the President’s ear) to stop the FSB from interfering in the lives of the Family. If the KGB had taught him nothing else, he had learned how to obey orders.

Putin quickly discovered that the agency might have changed its name, but it had retained its traditional paranoia in what he describes as ‘a constant state of tension’. ‘They were always checking up on you,’ he says. ‘It might not happen very often, but it wasn’t very pleasant.’ There were also petty restrictions, such as expecting FSB officers to take their meals in one of the Lyubanka’s canteens because the common view was that ‘only black marketeers and prostitutes dined in restaurants’.

Nor was he welcomed with open arms: Putin had demonstrated himself to be too close to Sobchak for the liking of many of his fellow officers, and had in fact turned his back on the KGB to take a job at City Hall, where he had declined an approach to spy on the mayor. Putin’s solution to the problem was one that he would follow from now on: lacking support among the existing hierarchy, he brought in his own team from the security services in St Petersburg, notably his friends Victor Cherkasov, Sergei Ivanov and Nikolai Patrushev, all of whom he had known either from Leningrad State University or from his early days in the KGB. And as a mission statement, he restored a plaque to Yuri Andropov which had been removed from the entrance hall.

As the nation teetered on the edge of bankruptcy, Kiriyenko was forced to announce that the Government would allow the Russian currency to slide to 9.1 roubles to the dollar, a fall of more than 50 per cent, which drastically reduced imports and shattered public confidence. Yeltsin sacked Kiriyenko and his entire cabinet soon afterwards, but this did nothing to ease matters. Apparently Putin, defying the risk of associating with black marketeers and prostitutes, was overheard in an Italian restaurant blaming Alan Greenspan, chairman of the Federal Reserve, for Russia’s plight. Hundreds of thousands were losing their jobs, people’s savings were becoming worthless and the shops had little or nothing to sell.

Yeltsin wanted to replace Kiriyenko with his faithful old war horse Viktor Chernomyrdin – a man well-known for Yogi-Bear-like malapropisms, including ‘the situation is utterly unprecedented—the same old story all over again!’ and ‘I’d better not talk, or else I’m going to say something...’ – but his appointment was blocked by the Duma. Yevgeny Primakov, former head of the SVR (the foreign intelligence service), who had served as foreign minister since January 1996, took over the post in September as a compromise figure acceptable to the majority of deputies. Primakov had turned down Yeltsin’s offer, but, as he later disclosed in his memoirs Years in Big-Time Politics, on leaving Yeltsin’s office he had run into Tanya-Valya, who persuaded him to accept. ‘For a moment, reason took a back seat,’ he wrote, ‘and feelings won out.’ As we will see, Primakov was far too independent and inquisitive for his own good and in less than a year he would be deposed.

ON 20 NOVEMBER Putin heard that Galina Starovoitova had been assassinated in St. Petersburg. Dr Starovoitova and her aide Ruslan Linkov were attacked by two men on the staircase of her apartment building. The 52-year-old democrat was shot three times in the head and died on the spot. Linkov was also shot in the head but recovered. Dropping their guns on the stairs, the killers fled in a waiting car.

Dr Starovoitova was a controversial figure, who had made many enemies. On frequent visits to the West she warned that Russia’s reformers were under attack by powerful groups ‘striving to restore the old economic and political system’, which sought to exploit nostalgia for Communist times. At one point, Yeltsin had made her his adviser on ethnic minorities. They had fallen out over Chechnya in 1994, but had later been reconciled.

The problem for her enemies was that Starovoitova – a doctor of psychology – could not be bought. She was planning to present to the Duma evidence of corruption by Communist members, and had just announced that she would run for the governorship against Yeltsin’s old adversary Vladimir Zhirinovsky, the nationalist leader she accused of trying to build ‘a criminal dictatorship’, when she was killed. One of her favourite targets was the Russian army. ‘Our military is not accountable to civil society and does not answer even to the President,’ she chided. Yeltsin suggested she should run the defence ministry, but she joked that Russia was not ready for a defence minister in a skirt.

On hearing the news of her assassination, Yeltsin described his friend as ‘my closest comrade-in-arms’. He sent his interior minister Sergei Stepashin, a veteran of Russia’s security establishment, to St Petersburg to find her killers. The main suspects were thought to be hitmen hired by the GRU, the foreign military directorate of Russia’s armed forces. The murder investigation took place under the personal direction of Stepashin (a former FSB boss and future Prime Minister). In June 2005 two hitmen, Yuri Kolchin and Vitali Akishin, were convicted of murder and sentenced to 20 and 23 years in prison, respectively. A few other suspects are still wanted in the investigation into Starovoitova’s death, which re-opened in 2009.

Meanwhile, Putin had launched the eighth reorganisation of the FSB in as many years as part of an economy drive. He abolished two departments (economic counter-intelligence and defence of strategic sites) and dismissed about 40 lieutenant-generals and major-generals and about a third of the central staff, reducing it from 6,000 to 4,000. As the axe had fallen mainly on those approaching or beyond pensionable age, it was argued that the service had lost its most experi enced officers, and indeed Putin’s intention had been to weed out the ones with the strongest links to the old Soviet system.

This was a difficult time for him and his task was made no easier by the death of his adored mother Maria at the end of 1998 after a long fight with cancer. He took leave to be at her bedside for her final days. Though he closed her eyes on her deathbed, in typical Putin style he did not show much emotion. If he wept, he did it in private. Meanwhile, his efforts had not gone unnoticed at the Kremlin. Yeltsin said later he appreciated Putin’s sense of decency, in ensuring that officers dismissed from the FSB had a ‘soft landing’, a new job or a generous pension. At the time, it is doubtful that Yeltsin was too well-informed about Putin’s cost-cutting efforts or his humanitarianism, but he was about to get to know him very well. Very well indeed.

AT A CABINET MEETING on 28 January 1999 Primakov pledged war against the speculators and black marketeers who he believed were guilty of economic crimes against the state. Boris Berezovsky was top of his list. Soon afterwards prosecutors and a squad of armed men in black masks raided Berezovsky’s companies in Moscow, the Sib neft headquarters and Aeroflot in search of incriminating documents. They left the Sibneft building with several boxes of materials. Berezovsky discovered to his fury that the Prime Minister had person ally ordered the raids.

At the same time, Yuri Skuratov began investigating Pavel Borodin over allegations that he had taken massive bribes from a Swiss engineering company called Mabatex, which had carried out multi-million dollar restoration work in the Kremlin. Skuratov, the son of a police officer, had begun his career as a law professor in Yeltsin’s home province. He had supported Yeltsin as the local Communist Party boss and later as a leader of democratic reform. In 1989, he joined the staff of the law department of the Communist Party’s Central Committee in Moscow. By 1991 he was a member of Yeltsin’s team as adviser to the KGB and later drafted the 1993 Constitution with Anatoly Sobchak, another of his targets.

When he was named Chief Prosecutor in October 1995, the opposition in the Duma welcomed him as someone who was politically neutral. He was provided with a dacha on the outskirts of Moscow by Borodin’s property directorate and drove around in an armoured Mercedes. By 1999, however, the general public knew only too well that Skuratov, despite his bravado and broad powers, had failed to prosecute any major figures involved in corruption or solve any of the contract killings of politicians and other prominent citizens.

Skuratov claimed in an interview with the New York Times that he had broken with the Yeltsin regime during the 1996 elections, when he was investigating the case against Lisovsky and Yestafyev. He had quickly learned that Kremlin denials were false, while top government aides pressed him to drop the case. Now he claimed to have documentary proof from the Mabetex offices at Lugano, Switzerland, that the company had provided credit cards to Yeltsin and his two daughters, Tatyana Dyachenko and Yelena Okulova. These documents also indicated that Mabetex had footed the bill for purchases made on those cards amounting to tens of thousands of dollars.

Putin and Olympic medalist Svetlana Gladysheva visit a ski resort in Sochi.

The case was just building up a head of steam when it emerged that Skuratov was open to blackmail. A man resembling him had been filmed cavorting with two prostitutes in a sauna while apparently high on stimulants. The film was first shown on RTR state television on 16 March. It caused a sensation, with stills taken from the video published in most Russian newspapers. Skuratov’s identity was never proven, and he claimed it was a case of mistaken identity and his enemies in the Kremlin were out to destroy his reputation. Although nobody knew for sure who had made the film – nor indeed who it really featured – it bore all the hallmarks of an FSB honey-trap. Then Putin stepped forward to confirm that the moonfaced naked man in the film was indeed the Prosecutor General.

On the same day as the raids against Sibneft, legend has it that Yeltsin summoned Skuratov to his dacha in Gorky-9 where, to his surprise, he found Putin at the President’s side. In front of Putin, Yeltsin ‘suggested’ Skuratov write his letter of resignation there and then. The prosecutor had little choice. Yeltsin laughed as he held out the document and shook Putin’s hand to pile on the humiliation.

Putin’s version of the story differs in important respects. He says there were four people at the meeting: Yeltsin, Skuratov, Primakov and himself. Yeltsin had put the videotape and copies of the photographs on the table and said, ‘I don’t think that you should work as prosecutor any longer.’ Primakov agreed. ‘Yes, Yuri Ilyich, I think that you had better write a letter of resignation.’ Skuratov thought it over, then took out a piece of paper and wrote out his resignation.

But Skuratov did not give up. His most powerful ally was Yeltsin’s rival, Yuri Luzhkov. As a regional leader he was a member of the Federation Council, the upper house of the Russian Parliament, responsible for overseeing the prosecutor’s operations. The council voted to support Skuratov, who then withdrew his resignation and released details of his half-finished investigation into the Kremlin restoration contracts. Luzhkov fanned the flames as part of his own aggressive political agenda and demanded that the prosecutor be allowed to complete his work.

On 24 March Yevgeny Primakov was flying to Washington for an official visit when he heard that NATO had started to bomb Yugoslavia. Primakov ordered the plane to turn around over the Atlantic and return to Moscow. This decision was dubbed ‘Primakov’s loop’ by the Russian media and it was wildly popular with the public. In fact, Primakov had become too popular, too ambitious and too dangerous for his own good. Such was the paranoia in the Kremlin that Yeltsin believed the Prime Minister was plotting with one of his closest aides, General Nikolai Bordyuzhey, to overthrow him.

Bordyuzhey’s rise had been meteoric and his fall was equally spectacular. The former KGB officer had been chief of the Federal Border Service when on 14 September 1998 he was appointed head of the all-powerful Security Council. Four months later, he also became Yeltsin’s chief of staff, making him one of the most powerful men in Russia. Bordyuzhey lost both posts in quick succession. On 19 March the bearded economist Alexander Voloshin, one of Berezovsky’s former business partners and a man singularly suited to this Byzantine world, replaced him at the Kremlin, and a few days later Putin took over the chair of the Security Council.

Nevertheless, Primakov continued to turn the screw on Berezovsky. On 5 April a warrant for his arrest was issued by the deputy prosecutor Nikolai Volkov, accusing him of misusing Aeroflot’s revenue. Berezovsky had never owned any Aeroflot shares, but he had access to millions of dollars in hard currency from the airline’s foreign ticket sales. Berezovsky was in Paris at the time and got the warrant quashed with a phone call to his allies in the Kremlin. ‘Primakov intended to put me in prison,’ Berezovsky says. ‘It was my wife’s birthday [and] quite unexpectedly, Putin came to the party. He came and said, “I don’t care in the least what Primakov will think of me. I feel that this is right at this moment”.’

Putin either knew or guessed that he was on safe ground. On 12 May Yeltsin sacked Primakov. Three days later the Duma attempted to impeach the President, but its efforts ended in humiliating defeat when the Kremlin, or its corporate allies, allegedly paid $30,000 for each of the votes to support him. The strain was too much for Yeltsin’s fragile health. He was too sick to see Jose Maria Aznar, Spain’s prime minister, providing Luzhkov with fresh ammunition to question his fitness for office. Russia, he declared, was not being run by Yeltsin but by a ‘regime’ in the Kremlin that included Berezovsky, his confederate Alexander Voloshin and Tanya-Valya.

Yeltsin, however, recovered sufficiently to nominate Sergei Stepashin (who had previously been his interior minister) as Prime Minister. There was no further opposition from the Duma and the appointment was confirmed by 301 votes to 55. The new premier promised to crack down on gangster capitalism, impose higher taxes on alcohol and fuel, and introduce a more efficient system of tax collection. With Chubais’ support (backed by the Interior Ministry’s 180,000 troops), he pledged to enact the laws demanded by the IMF as the price for its loan of $4.8 billion that would save Russia from defaulting on its foreign debts.

Mikhail Khodorkovsky, however, took the opportunity to default on a $236 million debt to a consortium of western banks and to shake off a number of minority investors in order to gain total control of Yukos. ‘If a man is not an oligarch,’ he told one journalist, ‘there is something wrong with him. Everyone had the same starting conditions; everyone could have done it. If a man didn’t do it, it means there’s something wrong with him.’ In early 1998, he had purchased another oil company, Tomskneft, and started to extract oil from its rich fields instead of developing Yukos’ own deposits. One of Tomskneft’s investors was Kenneth Dart, an American who owned 13 per cent of the stock. He used his vote to block Khodorkovsky’s plans to consolidate the company into Yukos in the hope of being bought out with a significant profit. Khodorkovsky, however, reacted by diluting the value of Dart’s shares through a series of slick financial moves until they were virtually worthless. Dart was heir to the Styrofoam coffee cup fortune and had plenty of money behind him. He mounted an expensive public relations campaign to portray the Russian as a thief in the world’s media. The matter was settled by a secret deal, in which Khodorkovsky acquired Dart’s shares, but it did nothing to restore his reputation.

Meanwhile, Putin had quietly been making his mark. On 11 June he attended a tense meeting with an American delegation to discuss the growing crisis in Kosovo. He impressed Strobe Talbott, the US Deputy Secretary of State ‘by his ability to convey self -control and confidence in a low-key, soft-spoken manner’. According to Talbott, Putin ‘radiated executive competence, an ability to get things done without fuss or friction (which had been his reputation in St Petersburg when I’d first heard of him.)’ Talbott went on to say that there was nothing bombastic about Putin: ‘None of the mixture of bullying, pleading and guilttripping that I associated with the Russian hortatory style’. He thought Putin was ‘just about the coolest Russian I’d ever seen. He listened with an attentiveness that seemed at least as calculating as it was courteous.’

Putin let Talbott know that he had done his homework by referring to the Russian poets that Talbott had studied at Yale and Oxford: Vladimir Mayakovsky and Fyodor Tyutchev – whose philosophy is reflected in such lines as ‘One can’t grasp Russia with one’s mind/ No measurements its bounds perceive/. A special fate for her’s designed/ In Russia one must just believe.’ The American found the experience quite unnerving.

In late July the prime minister of Israel, Ehud Barak, flew to Moscow for talks with Yeltsin about the Middle East. He returned home with the news that Stepashin would be replaced within a matter of days. Yeltsin subsequently admitted that his loyal lapdog had had no chance of succeeding him. ‘Even as I nominated Stepashin,’ he writes in Midnight Diaries, ‘I knew that I would fire him.’ So who was next in line for the ill-fated premiership? ‘The replacement that was mentioned to me,’ the Israeli prime minister said in a phone call to Bill Clinton, ‘was some guy whose name is Putin.’