THE MEN FROM the Prosecutor’s Office and the Ministry of Internal Affairs had planned it all with military precision. When the Tupolev 154 private jet landed at five o’clock on the morning of 25 October 2003, the pilot failed to spot two minivans with smoked glass windows waiting in the darkness at the end of the runway. This was, after all, merely a refuelling stop, and at that hour of the morning there were few people around the airport at Novosibirsk, deep inside central Siberia. Not until he had shut down the engines did the vehicles begin their short but highspeed dash towards the aircraft. The first those on board knew of the arrival of the vans’ occupants was a loud bang reverberating through the cabin as the Tupolev’s door was blown off its hinges. As smoke billowed around the cabin more than a dozen men in combat fatigues clambered on board, screaming at everyone on the plane to put their hands on their heads. The men from the FSB had arrived to arrest Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Putin’s threatened war against the oligarchs had stepped up several gears at once.

AS KHODORKOVSKY was bundled down the steps of the aircraft in handcuffs – his own security men were rendered helpless by the speed of the operation – he demanded to know the reason for his arrest. His offence, he was told, was failing to turn up at short notice as a witness in a criminal trial. He knew, of course, that this was a ruse, though he could not have known the detailed planning that had gone into it. Even while Putin was denying personal involvement, Roman Tsepov, former head of the private security firm which had guarded Sobchak, and who was present at Khodorkovsky’s arrest said: ‘It wasn’t Volodya, it was us. It was a job that had to be done for him’. Tsepov died some time later in a St Petersburg clinic in highly questionable circumstances.

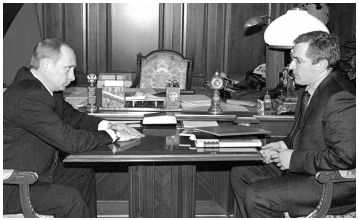

NOT at the round table: Once Russia’s richest man, Mikhail Khodorkovsky is now in prison on charges of fraud and tax evasion. Putin had warned him not to use his £15 billion fortune to meddle in politics.

It was not as simple as that, however. Although Tsepov’s men may have executed the plan it was – according to Khodorkovsky’s own superb intelligence sources – a man closer to Putin than any other who gave it the green light: Igor Sechin, the Grey Cardinal, the man who once sat in the corner of Putin’s office in St Petersburg and who had been rewarded with the job of heading Rosneft, the state oil company that subsequently acquired the huge assets of Khodorkovsky’s own oil company, Yukos.

With minimum delay, Khodorkovsky was flown back to Moscow under armed guard and deposited in a grim detention centre called the Sailor’s Silence (Matrosskaya Tishina), where he was locked in a cell with five other prisoners. Incarcerated so close to the president he had dared to provoke, the wealthiest man in the country was to breakfast each day on thin fish soup and tea, and dine on a buckwheat muffin spread with margarine. Much worse lay ahead.

The incarceration of Putin’s most powerful opponent sent shock waves through the oligarch community. Roman Abramovich, who had bought Chelsea Football Club four months earlier, was in London for the team’s match against Manchester City when he heard the news. Like everyone else, Putin was well aware that the two oil barons – Khodorkovsky of Yukos and Abramovich of Sibneft – had just agreed to merge their companies. Although Abramovich was fairly sure he was safe, Putin jailing his new business partner was just too close for comfort. One of his first actions was to place a call to Moscow, to his friend Alexei Venediktov, the maverick political commentator. He knew that Venediktov had his ears closely pressed to the Kremlin walls and had warned Khodorkovsky the previous June that he was going to be arrested sooner or later. At the time both oligarchs had laughed off the suggestion, but now Abramovich was anxious to find out if his best (probably his one and only) Russian media contact knew any more. He told Venediktov he would return to Moscow the following day and was anxious to meet with him. Venediktov was not so keen. He did not relish the prospect of journeying out of the city to Abramovich’s dacha, but the oligarch was insistent. He would be in Russia for only one day and it was very important that they talk, and in secret.

The radio journalist relented, and when he did arrive at the oligarch’s house he found it filled with flowers: it was Abramovich’s 37th birthday. When a man as rich and powerful as Abramovich celebrates his birthday, the floral tributes can be prodigious, but Venediktov was unimpressed. He suggested to his friend that he take the flowers and sell them on the street to put some food on the table for the poor.

After that inauspicious start, they got down to discussing the arrest. Seated at a table in his favourite Georgian restaurant, Venediktov told me soon afterwards: ‘Abramovich appeared stunned, nonplussed by the news. He had been sure of Khodorkovsky’s immunity. That was one of his few miscalculations. He had summoned me because he wanted to make it clear to me [and probably to Venediktov’s army of Moscow Echo radio listeners] that it was not him who had put Khodorkovsky in prison. I didn’t quite believe him and I told him so. He said, “Is there no way I can convince you?” I said he could try. He could convey his thoughts but my mind was my own and I would decide for myself.’

While Abramovich wanted everybody to know that he had nothing to do with having Khodorkovsky put behind bars, he was willing to spend only 24 hours in Moscow to clarify the matter.

The inference has been from certain critics that Putin, with his deputy Sechin’s encouragement had inspired his enemy’s arrest and the dismantling of Yukos, officially described as ‘the forced sale of assets’. The original explanation given to Khodorkovsky for his arrest came unstuck when the Prosecutor General’s office announced that he was being charged with massive tax evasion, fraud and theft amounting to $1 billion in total. It was widely rumoured that Khodorkovsky had been planning to buy the support of a considerable number of members of the Duma in advance of the elections scheduled for 7 December. The – unsubstantiated – theory goes that Putin had hoped that, like Berezovsky and Gusinsky, Khodorkovsky would flee the country if the frighteners were put on his closest executives; thus his right hand man, Platon Lebedev, had been picked up and accused of a $280-million fraud relating to the privatisation of a fertiliser company almost a decade earlier. Two other Yukos managers had been charged with tax evasion and murder. By refusing to be goaded by Putin in this way, Khodorkovsky was either demonstrating huge bravery or a colossal error of judgment.

The persecution continued. Not only were the offices of Yukos raided, but also those of the Yabloko party, for which four Yukos executives were standing as candidates for the Duma. The move ensured that the party failed to get the five per cent of the vote necessary to qualify for seats.

The President didn’t get it all his own way. The stabilisation of the Russian economy – the central plank of his policy – took a hefty blow as foreign investors rushed to get their money out. The stock market lost a tenth of its value in a single day. But if Putin had gambled on winning over the man in the street then he was definitely on to a winner. His personal popularity rose by two percent in the wake of his attack on the Yukos empire and the company’s shares leapt 4.1 per cent when, on 3 November, Khodorkovsky resigned as chief executive.

No one would deny that these events made Abramovich even richer: Putin’s favourite oligarch had first proposed the creation of Yuksi – the marriage of Yukos and Sibneft – at the beginning of the year, committing himself to the point of promising to pay a $1 billion penalty should he withdraw for any reason. But the driving force behind the company to which he was entrusting his future was now in jail, and in Putin’s Russia there are informal solutions to most issues. Abramovich had lost a close ally in the Kremlin when the President’s Chief of Staff, Alexander Voloshin, resigned in protest over the handling of the Khodorkovsky affair, but the move brought Abramovich and Putin even closer together.

WHEN the Air Landing Troops commander General Shamonov was injured in a road accident he received a surprise visit from Putin at the Burdenko Hospital – named after Nikolay Burdenko, the man who pioneered Russian neurosurgery.

Yukos had already bought 20 per cent of Sibneft’s shares for $3 billion in cash, valuing Abramovich’s company at $15 billion and giving it a 26 per cent stake in the combined group in return for the remainder of the sum. This left Abramovich in the unfamiliar position of being the junior partner and, with Khodorkovsky indisposed, leadership of the merged entity had passed, not to Sibneft’s CEO Eugene Shvidler, but to one of Khodorkovsky’s associates, Simon Kukes. This rendered the entire operation vulnerable to a political attack which it would not have to face if he – as Putin’s favoured oligarch – or Shvidler was in charge.

Just before the start of a meeting of shareholders on 28 November, Abramovich suspended the merger. Was he about to take advantage of the conglomerate’s new weakness for personal gain? Or was he acting on the President’s orders?

A core shareholder demanded that he should pay a penalty of five times the $1 billion agreed in the merger contract for unwinding it, return the $3 billion down payment with interest, and relinquish Sibneft’s 26 per cent in Yukos.

The exiled oligarch Leonid Nevzlin – a rogue Yukos shareholder – and two others subsequently offered to give up their shareholdings in return for Khodorkovsky’s freedom, but Khodorkovsky himself rejected the offer before anyone had a chance to consider it. Part of the reason was to emerge later when – incarcerated in a Siberian prison and serving an eight-year sentence – he made declarations on a website he was somehow able to maintain, proclaiming that he was Putin’s enemy and not Russia’s.

KHODORKOVSKY’S FINAL aim was – and probably still is – to achieve political power. He had made money, an unimaginable amount of money, building a business so huge that it was his country’s fourth biggest commercial enterprise. In short, he’d been there, done it, and now had other things to prove. Such success seems to have made him contemptuous of those who wielded political power but had never made their mark in business.

The extent of Putin’s control over Abramovich was made clear to me and writer Dominic Midgley when I put to the Kremlin an allegation Berezovsky had made to us in the course of research for our separate biography of Roman Abramovich.

At his heavily fortified office in Mayfair Berezovsky alleged to Midgley and me that Abramovich had made him sell his Sibneft shares for $1.3 billion when they were worth two or three times that amount (an allegation which has since become the subject of a High Court battle between the two men). Berezovsky further claimed that Abramovich turned up during his French exile and told him that unless he complied: ‘Putin will destroy our company and we will both end up with nothing.’

Back home that night, I communicated Berezovsky’s accusation to the Kremlin, making sure they knew that unless there was a swift response, the story – clearly detrimental to the President – would be published. The following morning I heard back from Moscow – not from the Kremlin but from the office of Abramovich, who had diligently refused to co-operate in any way with our biography of him. The oligarch was concerned that Midgley and I were getting ‘too much negative information’ and he was dispatching one of his most senior lieutenants forthwith to meet us in London. Abramovich was, it turned out, doing exactly what he had been told to do.

As Yukos ran deeper and deeper into trouble, Abramovich (or perhaps his Kremlin sponsors) saw a way to profit from the mess. Former Yukos manager Nevzlin’s efforts to penalise his new partner and to free his imprisoned one both having failed (his powers were greatly curtailed by the fact that he was now in self-imposed exile), Abramovich was free to forge ahead with a plan to unbundle the merger and profit from its abortion. If he thought he was being greatly helped by Putin’s dismissal of his Prime Minister Mikhail Kasyanov – whose crime had been to express his ‘deep concern’ over the way the Khodorkovsky business was handled – then Abramovich had not bargained for the appointment of his successor, Mikhail Fradkov, a former head of the Tax Police. Abramovich could expect no kid-glove handling by the new man, who was as hardline as his boss when it came to dealing with the oligarchs who, he believed, had tricked the nation out of 60 per cent of its assets.

If ever Putin had wanted an opportunity to turn up the heat on Abramovich, then this was it. He declined to take it, however. Abramovich surged ahead, using every technique in the book to get his money – and more – out of Yukos. At one point during that London meeting engineered by the Kremlin, I asked his right-hand man why the businessman didn’t simply repay Yukos the $3 billion he had received for the shares in Sibneft and call it a draw. ‘But they want more,’ he exclaimed.

The authorities were pounding Yukos for billions in taxes and penalties and the government had frozen its assets, making it unable to pay anyone.

By early September 2004 Abramovich’s holding company had clawed back 57 per cent of the 92 per cent it had transferred to Yukos, after a court ruled that the issue of the new shares Yukos had used to finance that stake was illegal. At another court hearing there was more good news for Putin’s man: the 14.5 per cent of his company he had transferred for 8.8 per cent of Yukos’ treasury sales was also rescinded. He then took further steps to start recovering the rest, for which he had received $3 billion in cash.

Why was the fate of these two oligarchs and their companies so different? In an interview with the newspaper Izvestia, Paul Klebnikov, the American editor of the Russian version of Forbes magazine, said: ‘I think one of them is simply a personal friend of the President. And the other is just an independent man. If the law is applied so strictly to one oligarch, why is it not applied in the same way to the other, who has offended public morals much more seriously?’

This point of view was widespread: if they condemned Khodorkovsky, why didn’t they condemn them all? The explanation from the powers-that-be was that if someone proved that Potanin, Aleksperov, Abramovich, Yevtushenkov, or whoever else it might be, had stolen – by failing to pay due taxes – vast sums of money from the state, and taken Yukos’ attitude of not wanting to return that money, then Putin could never forgive them. And why should he? Today, the steely-faced president is regarded as one of Russia’s strongest leaders. He would also argue that his is a policy not based on unproven generalisations, but rather on the kind of real investigations that are conducted in any other civilised state. After Khodorkovsky’s arrest, oil taxes collected rose instantly 15-fold, and although no one would claim it has stopped altogether, the misappropriation of Russia’s oil money has fallen dramatically. There are still problems: a number of companies have been extracting the cheaper oil from many of Russia’s wells, in particular in Evenkia. Of the thousands of wells containing oil, at least half have been abandoned. Barbarous methods of extraction have resulted in up to 25,000,000 tonnes of oil being left in the ground each year – that’s equivalent to the entire output of oil-rich Azerbaijan. Since his arrival in office, Putin has made it his business to challenge the companies responsible.

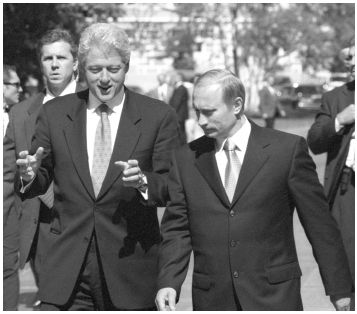

PRESIDENT (Bill) Clinton reckoned Boris Yeltsin had picked his successor when he first met Putin in September 1999 at an APEC meeting in Auckland, where Putin was standing in for his president. ‘Putin presented a stark contrast to Yeltsin,’ Clinton wrote in his diary. ‘ Yeltsin was large, stocky and voluble. Putin was measured and precise... and extremely fit from years of martial arts pratice.’

Just a few hours after he had given Izvestia his thought-provoking interview, Paul Klebnikov was murdered on a Moscow street as he walked home from the Forbes office on Ulitsa Dokukina. It was around 10 o’clock in the evening; four shots were fired at him from a passing car. It took five minutes for an ambulance to get to him and then, bleeding to death, he had to wait a further 20 minutes for the arrival of a surgeon at Municipal Hospital No. 20, a clinic with a good reputation. Putin had lost a useful media ally.

Klebnikov’s most obvious enemy was the subject of his biographical book Godfather to the Kremlin: Boris Berezovsky and the Looting of Russia. Berezovsky had sued Forbes in 1996 over an article in which Klebnikov called him ‘a mighty prince among bandits’, accusing him of the assassination of the television presented Vladislav Listyev. Only a few hours after Klebnikov’s death, Berezovsky said that he (Klebnikov) had been playing a dangerous game: ‘Obviously someone didn’t like the way he was behaving, and this someone decided to get rid of him… To publish a list of the richest people in the country [as Klebnikov had done in Forbes] was tantamount to giving their names to the Public Prosecutor. Standards are different…’