‘ON THE VERY DAY when he put it on for the first time, he pulled the sleeve of the shirt down over his wrist so that no one could see it, because he felt… well, a little embarrassed. Now he doesn’t give a damn,’ says Vladimir Putin’s friend, referring to his leader’s $60,000 Patek Phillipe Perpetual Calendar gold wristwatch. In August 2009 he gave this watch to the son of a shepherd during a one-day visit to Tuva.

In its place he acquired a Blancpain watch, which costs around $8,000, but was obliged to part with that too during a visit to a weapons factory in Tula. Viktor Zagaevsky, one of the factory workers, who had just asked a question about an economy problem, suddenly called out, in a fit of boldness: ‘Vladimir Vladimirovich, give me something to remember you by!’ Putin took off the Blancpain and handed it to him.

SUCH GESTURES OF generosity put Putin in danger of becoming the political equivalent of Elvis Presley, who would buy expensive cars and jewellery for some poor person he saw looking longingly into a showroom window. When Russia’s chief rabbi, Berel Lazar, went to his Novo-Ogaryovo residence to tell Putin he was setting up a fund to build a Jewish museum of tolerance, the man who once told Jewish jokes surprised him by saying without hesitation: ‘Good idea, I will donate one month of my salary to the fund’. A generous gesture; one month’s salary was equivalent to more than £8,000.

ALWAYS ONE to surprise, Putin declined his chauffeur driven Zil limousine and drove himself in his beloved 1956 GAZ-21 Volga when he attended the opening of the Adler tunnel near Krasnaya Polyana.

When I heard about the two vanishing watches I went back to mine and Putin’s mutual friend and asked him: How does Putin see fit to buy such expensive timepieces when George Bush always sported a $50 Timex? ‘Because one is Vladimir Putin and the other is George Bush. It’s as simple as that.’ When Lord Browne was asked if he believed that Putin was now a very rich man his reply was diplomatic but interesting: ‘Who isn’t? I’m sure his family is. But you never know, I don’t suppose anyone knows how much money he’s got. Who knows that...?’

SO HOW RICH is Putin and where has it all come from? One man has devoted much of his recent life to finding the answer to those questions: Stanislav Belkovsky.

Mr Belkovsky is a Russian political expert with contacts deep within the Kremlin and the White House, and he believes the Russian leader is now one of the richest men in the world, with a fortune close to $40 billion. It has to be said that not many in Russia pay attention to Belkovsky’s assertions and his frequent appearances on tabloid-type sensational television programmes do little to enhance his personal reputation.

When he was asked at a press conference on 14 February 2008 whether he was the richest person in Europe, as some newspapers claimed, and if so, to state the source of his wealth, Putin said, ‘This is true. I am the richest person not only in Europe, but also in the world. I collect emotions. And I am rich in the respect that the people of Russia have twice entrusted me with the leadership of such a great country as Russia. I consider this to be my biggest fortune. As for the rumours concerning my financial wealth, I have seen some pieces of paper regarding this. This is idle chatter, not worthy of discussion, plain bosh. They have picked all this from their noses and smeared it across their pieces of paper. This is how I view this.’

BELKOVSKY, IN HIS book (which collects dust on the shelves of all major bookstores in Moscow – contrary to assertions about all such writings being suppressed) alleges that Putin effectively controls 37 per cent of the shares in Surgutneftegaz, an oil exploration company which is also Russia’s third biggest oil producer. That shareholding alone would be worth $20 billion, but that’s not all: Belkovsky’s sources claim Putin also owns 4.5 per cent of Gazprom and at least 50% of Gunvor, a mysterious Swiss-based oil trader founded by his friend Gennady Timchenko, through which the state company Rosneft sells 30-40% of its oil.

‘He may also own or have some interests in other business that I don’t know about yet,’ says the reckless political expert. ‘Putin’s name doesn’t appear on any shareholders’ register, of course. There is a nontransparent scheme of successive ownership of offshore companies and funds. The final point is supposedly Zug.’

The liberal group struck back, granting Kommersant an interview with Oleg Shvartsman, a previously obscure businessman, who claimed that he secretly managed the finances of a group of FSB officers. The Secret Servicemen had, he said, $1.6 billion banked in various offshore accounts – not bad for men whose average pay is less than $50,000 a year. Shvartsman declared the officers were involved in ‘velvet reprivatisations’ – the forcible acquisition of private companies at below-market value with the intention of turning them into state-owned firms.

The First Deputy Chairman and CEO of Alfa Bank, Oleg Sysuev, described Shvartsman’s Kommersant interview as ‘very serious, truthful and scary’. Quoting Vladimir Putin, he said that ‘there are lots of idiots who want to rub shoulders with United Russia – and in this case – to do good turns to those in power’.

Senator Farkhad Akhmedov, co-owner of Nortgaz, on the other hand, said that ‘people like Shvartsman must be turfed out of the business community’. Akhmedov promised to ask the Prosecutor’s Office to ‘probe into the circumstances of the case’ because if ‘businessmen are stuck in their holes, there will be as many Shvartsmans as snow in the Arctic’.

The head of the Federal Politician Council of the Civil Force Party, Alexander Ryavkin, sacked Oleg Shvartsman from the party’s supreme council following a request by party leader Mikhail Barshchevsky. Barshchevsky said in an interview with Kommersant that they had no knowledge of Mr. Shvartsman’s ‘dubious dealings’.

Our ‘mutual friend’ would not be drawn on the subject. When I put the political writer Belkovsky’s assertions to him, his response was brief and uncharacteristically muted: ‘I know nothing [of this], if you want to print it, print it. I would not confirm this information to you’.

It is no secret that the rich and powerful men close to Putin include Gennady Timchenko, owner of the oil company Gunvor, and Yury Kovalchuk, who heads the Russia Bank and is its largest shareholder. Forbes lists him as the 53rd richest person in Russia and estimates his fortune at $1.9 billion. Kovalchuk and Putin are long-standing acquaintances, but Kovalchuk, who is regarded as an exceptionally astute operator, made his first millions long before Putin arrived in Moscow. In May 2008 Kovalchuk won the right to buy a controlling packet of shares in the newspaper Izvestia from Gazprom. The newspaper is among the most widely-read publications in Russia and is regarded as being Russia’s ‘voice’.

To his credit, Kovalchuk does not interfere in the paper’s editorial policy, so his media empire does not lose ‘journalists with conscience’, as happened frequently in the case of newspapers belonging to Berezovsky and Gusinsky.

IN GENEVA, WHERE he lives with his wife Elena and their three children, Gennady Timchenko refused to see me and share his views about Vladimir Putin. But in a penthouse office high above the City of London, his UK spokesman Stuart Leasor told me later: ‘They [Putin and Timchenko] know each other, they met in the early 90s and they see one another on certain occasions, but I wouldn’t say they were friends. Mr Timchenko financed a judo club* in St. Petersburg with which Mr Putin also has a connection, but that doesn’t make him Putin’s bagman. It does no harm to Gunvor and [Timchenko’s other company] Volga Investments to let people believe they are friends if they want to, but that’s stretching things.

‘As for Mr Putin having anything to do with Mr Timchenko’s business, there was a great conspiracy theory about who the mystery third party shareholder in Gunvor was and people put two and two together and made five – i.e. was it Putin? Gunvor made a big mistake in refusing to talk to the press – oil traders historically only give out information on a need-to-know basis – but I can tell you the third party was a Swedish businessman who was not an oligarch – in Russia you’re a pauper unless you’re a billionaire. He had 10 per cent of the company. It wasn’t Putin.

‘Gunvor has been accused by the Yukos camp of screwing the Russian company because their company’s main assets were taken over by Rosneft and, like Gunvor, Rosneft has a trading arm in Geneva, for healthy tax reasons. The trading arm of an oil company is most important. It’s one thing to go to a producer and buy 100,000 tonnes of oil but how do you get it from the wellhead to where you want it to be? Gunvor has excellent facilities and a good relationship with Russian Railways. Mr Timchenko knows how to play the Russian game.’

WHEN I ASKED Leasor about the worrying image of his boss conveyed to me by my diplomat friend, he replied: ‘Mr Timchenko lives a pretty ordinary life. He is not like those steely-eyed, no-neck oligarchs [and here he names three prominent oligarchs] who had people killed off. He doesn’t have a gang of bodyguards following him everywhere; when he goes on holiday with his wife and children he stays in a relatively modest villa, not in a seaside palace or on an ocean-going yacht, and he wears Pringle diamond-pattern pullovers.

Putin rebuts the charge that while Russia’s poor get poorer, those men close to him are getting richer. ‘[If] you know who and how, write to us, to the Foreign Ministry, if you are so confident,’ he said in an interview with Time magazine, adding, ‘I presume you know the names, you know the system and the tools. I can assure you and everyone who would listen to us, watch us and read us, that the reaction would be swift, immediate and within the prevailing law.’

Although the names to which he refers are known to most of his citizens, there is no record of anyone having written in response to his statement. In any event, Putin is immune from prosecution under article 91 of the Russian Constitution, which states that ‘A president of the Russian Federation who has ceased to exercise his authority has immunity. He cannot be called to account under criminal or administrative liability for deeds he has committed during the period of exercising the powers of President of the Russian Federation, or be detained, arrested, searched, interrogated or placed under personal surveillance, if the said deeds were committed in the course of dealing with matters connected with his exercise of the powers of President of the Russian Federation. The immunity of a President of the Russian Federation who has ceased to exercise his powers extends to the domestic and service premises he occupies, the transport vehicles he uses, means of communication, documents and baggage belonging to him, and his correspondence.’

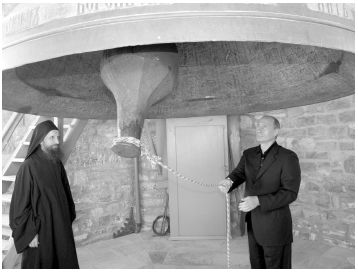

PUTIN PUTIN visits the St Panteleimon Russian Orthodox Monastery on Holy Mount Athos.

ONE LEADING RUSSIAN academic says of the ‘billionaire President‘ theory, ‘If he were in possession of a fantasy fortune he would have a hard time spending it. Can you really imagine Putin, Russia’s Robin Hood, joining the ranks of the oligarchs in a spotlight he’s destined to live in for the rest of his life? He would face the total contempt of the Russian people, and he knew that very well before putting his Robin Hood hat on. If he were an oligarch at heart, he would have opted out of the Russian presidency a long time ago – he would make much more money out of public life. Putin drives Ladas, not Bentleys, he likes fishing in Siberia, not swimmimg on the Côte d’Azur; and skiing in Sochi, not Courchevel. He’s a patriot and an action hero, the discreet charm of the bourgeoisie in parochial Zug or Lichtenstein is not his destiny. His mission is Russia, Russia and once again Russia.’

In any event, no one can question the fact that Russia has prospered under his leadership. While George Bush and Tony Blair concerned themselves with Iraq, Putin rarely gave time to what he regarded as irrelevancies, and instead concentrated on building Russia’s energy power. As a result, by 2007 net inflows of foreign investment had grown to $10 billion from $1.62 million in 2004. In that period America had doubled its import of Russian oil to 400,000 barrels a day, and Europe had increased its requirement of the commodity from 12 per cent to almost 30 per cent.

But it was Russia’s gas that Europe needed even more: Europe bought close to 150 billion cubic meters – about 40 per cent of its entire need. And furthermore, a number of leading analysts have noted that Russia’s control over gas, which is Europe’s ‘life blood’, is on the increase. Germany alone took 40 billion cubic meters; no wonder Chancellor Merkel was reluctant to castigate Putin for Russia’s military action in Georgia. Meanwhile China and, to a lesser extent, India, were buying everything Russia had to sell – not only oil and gas but nickel, copper and coal. And as for coal, the Ukraine is almost entirely dependent on Russia for fossil fuels – a reliance that the NATO countries could never hope to cater for should the country incur Putin’s wrath by responding to its overtures. More than one leading analyst pointed out that Russia was consolidating its grip on Europe’s very lifeblood. Its economic confidence was growing by the day and the West was on notice that it would pay a high price for intruding on its buffer zones.

Putin had the brilliant Alexei Kudrin – educated at the University of Leningrad and another ‘graduate’ of Mayor Sobchak’s office – to thank for masterminding the upswing in Russia’s fortunes, and as a result he was the only remaining liberal reformer to survive the Cabinet reshuffle in 2007, which even cost German ‘the thinker’ Gref his job.

However, even Kudrin was incapable of improving Russia’s fortunes when it came to producing goods other than its natural commodities to sell on the world market. Tourists shopping in Moscow and St Petersburg for Russian-made products would soon discover that most of what they took home was made in China.*

Kudrin left the Russian government after a spat with Dmitri Medvedev in September 2011 but many believe he will be restored to high office once Putin is President again.

IN DECEMBER 2009 one of Khodorkovsky’s lawyers, Robert Amsterdam, joined the chorus of those anxious to find out what was happening to Russia’s assets. He riled Putin when he demanded, ‘What happened to the country’s largest, most transparent and most successful oil company, and who pocketed billions from [its] illegal expropriation?’

The previous month Putin had likened Khodorkovsky to the Chicago gangster and killer Al Capone, who was accused of many crimes but ultimately charged and jailed for tax evasion. And in an emotional outburst when he was asked in a subsequent televised call-in programme when Khordokovsky could expect to be released from prison, Putin went off-message and declared: ‘Unfortunately, no one recalls that [any] of the Yukos security chiefs is in jail too. Do you think he acted on his own initiative and at his own risk? He had no actual interest. He was not the company’s main shareholder. It’s obvious that he acted in the interests and under the directives of his bosses. How he acted is a separate matter.’ And then he added a damning sentence: ‘At least five murders have been proven**.’ Amsterdam’s response was swift: ‘Leaving aside for just a moment the fact that Khodorkovsky is not a murderer, and has never been charged [with] involvement in any such violence, the logic and timing of this argument is ridiculous.’

BY NO MEANS EVERYONE has shared the advocate’s accusatory view. His client is described thus by the highly charged Moscow-based American banker Eric Kraus: ‘Khodorkovsky – and his lieutenants, the vicious Nevzlin and Lebedev – were notorious for callous brutality. The privatisation of Apatit alone filled up a medium-sized graveyard in the Urals. Russia may be a sometimes brutal place, but people like him made it far more so. Despite the best efforts of the Russian state, Yukos/Menatep retains control of its stolen billions parked abroad (it is for this reason that the Russian administration rightly fears Khodorkovsky – clever, vicious, infused with a sense of mission, with unlimited access to Western corridors of power and controlling a multibillion dollar war chest – back on the street he could be infinitely more pernicious than Berezovsky). This money is channelled through a dense network of political fixers, right-wing think tanks, Washington political operatives, PR and government relations firms (notably APCO, run, disconcertingly, by one Margery Kraus… no relation!), law firms such as Robert Amsterdam (essentially a very effective political huckster posing as an attorney), with scores of Western public figures on the payroll.’

Shortly before Khodorkovsky’s arrest in October 2003 Putin had one of his quite frequent meetings with Lord Browne of BP. He knew Browne had seen Khodorkovsky about investing in Yukos, but without success. Khodorkovsky had unnerved Browne with his talk about getting people elected to the Duma, about how he could make sure oil companies did not pay much tax, and about the powerful people he controlled. Putin’s comment was illuminating: ‘I have eaten more dirt than I need to from that man,’ he said.

Dirt? Browne, ever the English gentleman, was not offended, though he says he believed that the interpreter had cleaned even that up in his translation.