‘VLADIMIR IS THE SAME person as he was as a child,’ says someone who has known him for more than 20 years, when invited to share his views on the Russian leader’s psychological make-up. ‘He can be a Machiavellian so-and-so. He has never trusted America, particularly Bush, and he didn’t believe a word Kissinger said. Clinton? Well, Vlad liked him, but Clinton wasn’t on his level. He believes, he knows, the United States was out to plunder the Russia he is so proud of, using the oligarchs, and that Alan Greenspan had carefully worked out a plan to that end. As for Barak Obama, well, the jury’s still out.

‘You must understand that Putin is a man who acts responsibly. He doesn’t attack first, he is a peace-loving man. But if someone encroaches on the interests of his country – whether it is little Georgia or mighty America – there will be a commensurate response.’

PUTIN’S PSYCHOLOGICAL make-up was also studied in some detail by one former diplomat who worked with him and says: ‘He is very clever in that he doesn’t make enemies – apart from the obvious ones like Khodorkovsky, where he obviously had no choice. Where he has replaced people who were in power under the old regime, he hasn’t cast them out into the desert. They always got new appointments, maybe a little less important ones, but probably more financially rewarding by way of compensation. He is a person who cannot abide having enemies, because he knows you can’t control them and he has to watch his back all the time’.

Evidence that he cannot abide confrontation is shown in the treatment of his cabinet. He avoids going to meetings, knowing full well that they will probably end in full-blown battles. Afterwards he will see members individually, listen to their arguments and give the impression that he agrees with each and every one of them. Then he goes away and proceeds on the course he always intended to.

The senior British diplomat who briefed me on his return to London added this: ‘You know the situation in the Kremlin when he was President was that things hadn’t actually changed under Putin as much as people thought they had. It’s still a very Byzantine system and you don’t know who exactly has the power. I have a feeling that if you went to see the boss in any department – including Dmitri Medvedev’s now – you would open the door and there would be Putin. He has a very big job in balancing the different centres of power and in that respect he is extremely clever. He pulls it off every time, but he knows that nobody – I repeat nobody – devotes as much thought and attention to the detail of running the country as he does and that puts him on a higher plane than anyone who serves him.’

One of Putin’s oldest friends, Sergei Roldugin, sums him up in more human terms: ‘He was always a very emotional person, but he just couldn’t express those emotions. I often told him how terrible he was at making conversation and that’s one of the reasons he has no friends other than the people who work with him.’

Nevertheless, Roldugin adds: ‘Volodya has a very strong character. Let’s say [when we were young men] that I was a better soccer player. I would lose to him anyway, simply because he’s as tenacious as a bulldog. He would just wear me down. I would take the ball away from him three times and he would tear it away from me three times. He has a terribly intense nature, which manifests itself in literally everything.’

Roldugin is equally interesting on Putin’s hunger for learning: ‘Sometimes Vovka and I would go to the Philharmonic after work. He would ask me about the proper way to listen to a symphony. I tried to explain to him about Shostakovich’s Fifth Symphony; he can tell you a lot, because he loved it terribly when he first heard it and I explained it to him. And then Katya and Masha took up music. I’m the one to blame for that.

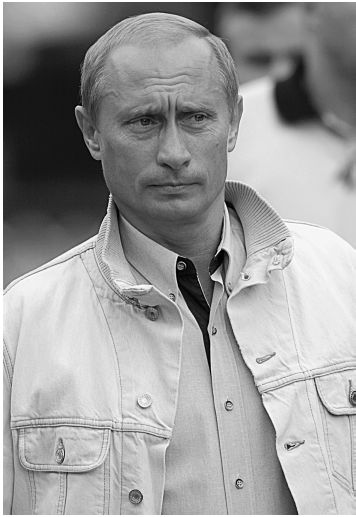

MEETING with representatives of the democratic youth antifascist movement NASHI (Ours) in the Sochi presidential residence, Bocharov Ruchei.

‘I’m absolutely convinced that our lecturers, with their highfalutin talk about music, are wildly wrong. The propaganda for classical music is really missing the mark. I explained to Volodya what a normal person should see and hear. I would say, “Listen, the music has started. That’s the peaceful life – they’re building communism. You hear that chord tati, pa-pa? And now the fantastic theme is coming in. Look, there it goes – those brass instruments are playing. That theme will grow. And there’s the peaceful theme, from the beginning. The two will clash now, here and there, here and there.” He just loved this terribly.’

Putin’s passion for music – although he says that Lyudmila is responsible for ‘dragging me to the opera’ – is not the only side of the friend Roldugin remembers so clearly: ‘Once, at Easter time, Volodya called me to go to see a religious procession. He was standing at the rope, maintaining order, and he asked me if I wanted to go up to the altar to take a look. Of course, I agreed. There was such boyishness in this gesture – “nobody can go there, but we can” [he said]. We watched the procession and then headed home. We were waiting at a bus stop and some people came up to us. Not thugs, but students who had been drinking. “Can I bum a cigarette off you?” one of them asked. I kept silent but Vovka answered: “No you can’t.” “What are you answering that way for?” said the guy. “No reason,” said Volodya. I couldn’t believe what happened next. I think one of them shoved or punched Volodya. Suddenly somebody’s socks flashed before my eyes and the kid flew off somewhere. Volodya turned to me calmly and said “Let’s get out of here.” And we left. I loved how he tossed that guy! One move and the guy’s legs were up in the air.’

Roldugin’s anecdote illustrates how Putin’s prowess in the martial arts allowed him to overcome his diminutive stature when – literally – push came to shove. When his friend Silvio Berlusconi suffered a broken nose, cuts and two broken teeth after being hit with a souvenir model of Milan’s gothic cathedral following a 2009 rally in the city, Putin telephoned him to praise his ‘macho behaviour’ in the wake of the attack. Dmitri Peskov said Putin had told the Italian leader that he ‘had behaved in a manly way in an extreme situation’.

ONE TRAIT WHICH bothers those who come into regular contact with him is his inconsistency, something which is hard to spot from his cool, calm and calculated public demeanour. ‘Vladimir can be charming one day and vile the next, there’s no accounting for his mood swings,’ says a prominent Russian businessman who has had many encounters with him. ‘You rarely get to know what causes him to change so drastically in such a short space of time.’

On the other hand, someone who has spent a considerable time in Putin’s company admits: ‘If you do what he tells you to, you’re safe; if you don’t, you are liable to get the rough end of his tongue or even see him weep.’

For a man who has been seen to weep in public just once – at Anatoly Sobchak’s burial – that seems an extraordinary admission. But according to Lyudmila he burst into tears that flowed for hours on the afternoon of Black Friday – Friday, 3 September 2004 – after being told that dozens of children were among the hostages shot or burned to death in a siege at a school in Beslan, North Ossetia.

Two days earlier Putin had been on holiday at the presidential residence, Bocharov Ruchei, in the hills above Sochi – his home away from home. It was a hot day and the president was making the most of the sub-tropical climate he enjoys so much on his frequent vacations there. He had already found time to swim in the Black Sea, within view of the naval ship which is always on duty there while the city’s most exalted resident is in town.

And then came the horrifying news. An armed group, mostly Chechen and Ingush terrorists, had broken into School No. 1 on Comintern Street in the town of Beslan. They had taken about a thousand people hostage, forcing them into the school sports hall, which they immediately mined. There was a particularly large number of people in the school that day as it was the beginning of the school year, and many of the children had arrived with their parents. The bloodbath began at exactly 9.30 a.m.; seven people were killed in the first attack.

Twenty minutes after the siege began Putin returned to Moscow. This was the second time in the last eight days that he had had to interrupt his holiday: 10 days earlier he had returned to the capital after terrorists blew up two passenger aircraft with a loss of 90 lives. It was clear that the terrorists had launched an all-out war.

SOON AFTER HIS plane landed Putin proved he meant business by conducting a meeting with Rashid Nurgaliev, the head of the Russian Ministry of Internal Affairs, Vladimir Ustinov, the Prosecutor General, Nikolai Patrushev, director of the FSB, and General Vladimir Pronichev, commander of the Russian border guards. Nurgaliev was to say later that Putin was very angry: ‘I have never seen the man in such a temper. He was in a vile temper’. This is disputed by the man himself, who told the American interviewer Mike Wallace on the 60 Minutes programme in May 2005: ‘I don’t remember one time in my five years as President of the Russian Federation that I lost my temper. I think that this [would be] absolutely unacceptable.’

Putin’s first action was to place a call to North Ossetia’s President, Alexander Dzasokhov, ordering him to hand over command of the counter-terrorist operation to the FSB. That allowed him to send in the Spetsnaz, his Russian commandos under the command of General Tikhonov. He went on to order the closure of North Ossetia’s borders and barred all flights in and out of the capital, Vladikavkaz. Then he disappeared from public view for the ensuing events, apart from a brief television appearance the following morning to declare that his main concern was for the lives of the hostages. For the following two days Putin never left his Kremlin office other than to pray in the adjoining chapel. He grabbed a few hours’ sleep on a makeshift bed, but admits that he sorely missed his daily exercise routine, which he could rely on to keep him focused.

Just as they had done at the outset of the terrorist act in Dubrovka, the bandits demanded that their mobiles should not be switched off. When an explosive device was set off in the sports hall, the children and teachers tried to flee, but a number were shot from behind. At this point special forces troops of the Alfa group rushed in to save the children. One of the soldiers was the fourth to be carried out. He had died with a child in his arms, trying to shield the youngster with his own body.

The total number killed was 334, of whom 186 were children – children younger than Putin’s own daughters.

SHAMIL BASAYEV was to say later that Beslan had been chosen by the Chechens because its airfield was used by Russian fighter planes during the bombing of Grozny, although he admitted later that he would have preferred to target a Moscow school, but such an operation was beyond his financial limitations.

At 4 a.m. that morning, Putin boarded the plane kept on standby to take him to Beslan. Once there, he visited hospitals treating the injured in the dead of night, though few of the town’s 35,000 inhabitants were asleep. This was one of the toughest days of his presidential life: 700 of his countrymen had been saved but hundreds had perished.

Putin made a brief television statement in which he admitted the weakness of the existing security system. ‘The weak get hit,’ he declared. His whole appearance showed that he was extremely tired and emotional. ‘It’s hard to speak. A terrible tragedy has taken place in our country. Throughout the last few days, each one of us has suffered deeply and felt in his heart everything that has gone on in the Russian town of Beslan…’

AFTER A LONG ENQUIRY Deputy Prosecutor General of Russia Nikolai Shepel was later to find no fault with the security forces’ handling of the hostage crisis: ‘According to the conclusions of the investigation, the expert commission did not find any violations that could be responsible for the harmful consequences’. To address doubts, Putin launched a Duma parliamentary investigation led by Alexander Torshin, resulting in a report, which identified ‘a whole number of blunders and shortcomings’ by the local authorities.

IN THE DAYS following the attack Putin took steps to consolidate both his own power and that of the Kremlin. He signed a law which replaced the direct election of regional governors with a system whereby they are now proposed by the President of Russia and approved or disapproved by the elected legislative of the federal subjects. The election system for the Duma was also amended, eliminating the election of Duma members by single mandate district. The Kremlin went on to tighten its control over the Russian media, so it came as no surprise to Putin when his critics charged that his circle of siloviki had supposedly used the Beslan tragedy as an excuse to increase their own power and return to the country’s authoritarian past. America’s Secretary of State Colin Powell said that Russia was pulling back on some of its democratic reforms, while George Bush expressed concern that Putin’s further moves to centralise power in Russia ‘could undermine democracy there’ – a comment Putin treated with contempt.

VISITING the Orlyonok (Little Eagle) All-Russian Children’s Centre on the Black Sea coast near Tuapse.

Dismissing foreign criticism as Cold War mentality, Putin resisted the opportunity to remind Bush of how power in the US was centralised in Washington, leaving it to his Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov to remind the Americans that Russia had its own affairs under control..

Putin’s undoubted pride in Russia is matched only by his love of his native city, the city he still often refers to as Leningrad. Known as the Venice of the North because of its 300 bridges, St Petersburg is rated worldwide for its culture. Pushkin, Nabokov and Tolstoy all wrote there and Dostoevsky set his Crime and Punishment in the city. Millions of tourists from all over the world flock to Russia’s second biggest city – and Putin’s home town – annually, many to inspect the incredible collection of three million pieces of artwork from the Stone Age to modern times in the Hermitage Museum, part of the Winter Palace. On some days the visitors almost fill St Isaac’s Square, their cameras pointed upwards towards the towers of St Isaac’s cathedral, the fourth highest domed cathedral in the world.

If his rise to ultimate power brought about radical changes at the expense of some freedom of expression and democracy as other nations know it, Putin can be appreciated for having instilled national pride, the kind of pride he harbours personally for the city of his birth. Just days before he hosted the G8 summit in St Petersburg in July 2006 he received the ‘happy news’ that Shamil Basayev, the butcher of Beslan, had been executed by the FSB in the Ingush village of Ekhazhevi. This was a moment in Russian history equalled only in subsequent years by the Americans’ capture and killing of Osama Bin Laden.

The happy news did much to boost Putin’s mood for the great show-off event of his presidency. He had easily outspent the sums lavished by his guests on previous summits. He had restored the Konstantinovsky Palace, founded by Peter the Great, to its former magnificence and even ensured that rain would not fall on his parade by ordering Russian fighter planes into the air to ‘burst’ clouds before they could reach the skies over the city.

Just in case anyone thought that he was genuflecting in the face of George W. Bush and Tony Blair, Putin referred to America in his presummit State of the Union address as ‘Comrade Wolf ’ and warned the British Prime Minister to stay clear of making corruption charges by telling him he knew all about Scotland Yard’s investigation into the dealings of his chief fundraiser, Lord Levy.

It was evident to one and all that Putin’s psyche was in good shape, but what of his physical condition?

Both during his past presidency and his turn as Prime Minister, Putin has pursued a punishing keep-fit programme in order to maintain his exceptionally high energy levels. His long morning runs and marathon swims would defeat many a man half his age. He has no alarm clock – he wakes when he is ready – eats modestly only when he is hungry and these days, as has been said, rarely drinks anything stronger than tea, although he will often clutch a glass of wine to make drinking guests feel comfortable. He scarcely ever leaves for Moscow before noon, regularly works in his office past midnight, and never gets into his bed before 2 a.m.

A former European ambassador to Moscow tells me: ‘He called me one night to suggest we went out “right away” to ski. I said “Vladimir, it’s past midnight”. “Exactly,” he replied. “The slopes will be empty”.’ The ambassador went, although he resisted Putin’s persistent efforts to get him on skis.

IT CAN BE SEEN that right from boyhood Putin has never been an easy man with whom to make friends and his friendship can easily be lost. On a political level that friendship with Tony Blair was severely strained over the British Prime Ministers’ pro-American stance during the Iraq war. But really it was on a personal level that Putin decided he wanted nothing more to do with Blair. No one was more acutely aware than Putin that the British Prime Minister had insulted Russia by sending his bumbling deputy John Prescott to represent him at a most significant event in Russian history. The 2005 celebrations in Moscow were to pay tribute to the Russian fallen on the 60th anniversary of the Allied victory over Nazi Germany – the most important day in the nation’s commemorative calendar. Presidents Bush and Chirac and Chancellor Schroeder all turned up in person.

What Blair had thrown away, France’s new president, Nicolas Sarkozy, picked up when he and Putin met for the first time following the G8 summit in June 2007. However, it seemed to many observers that the felicitations had gone a little too far when Sarkozy turned up late for a press conference – and seemingly a little the worse for wear – explaining that he had been with Mr Putin. His explanation for slurring his speech and nervous laughter as he invited a stunned audience of reporters to question him was that since he was running late he had taken the stairs four at a time: ‘I do not touch a drop of alcohol,’ he said.

A French journalist’s account of a meeting with him some time later in Moscow is worth recounting: ‘Sarkozy does not touch a drop of alcohol, so something else explained why his spirits were so high when he regaled us late last night on his dinner with Vladimir Putin. Sarko was unstoppable as he held forth in a little room in the National, the old Soviet hostelry, now transformed into a luxury hotel, which is opposite the Kremlin and Red Square. In three hours at Putin’s dacha, two minds had met as they surveyed the world and Russia’s resurgence as a power, Sarko said: “It was a long, very long discussion. Enthralling, very intimate. I felt a real desire to exchange ideas and to understand”.

‘Something seems to happen to Sarko when he meets Putin. It was after their first meeting, at the G8 summit in Germany last June, that he acted like such an excited schoolboy that the video of “Drunk Sarko” became a YouTube hit. The French President arrived in Moscow talking of Putin’s “brutality” with Russian natural gas and warning how tough he would be with the uncooperative Kremlin. The cosy old Franco-Russian days were over and we would see what we would see, as the French say. Yet there he was overflowing with admiration for the soonto-resign Tsar — and claiming that he had won a big concession from him over policy on Iran’s nuclear programme.

‘It seemed once again that Sarko was incredulous that he was playing world statesman, accepted as one of the big-boys, dans la cour des grands. Putin, he said, had confided in him his possible plans for staying on in power by becoming Prime Minister once he stands down as President next year. He had sounded Sarkozy out on his own ideas for putting a two-term limit on France’s five-year presidency. Putin is weighing the pros and cons of continuing power and he is extraordinarily lucid on the matter, said Sarkozy.

It is always fascinating to see Sarkozy up close like this. He was even joking that he had something in common with Putin because he had been chief of the French secret service for four years – as Interior Minister under Jacques Chirac. “What makes you think I’m an ordinary President?” he quipped to the group of reporters who had come from Paris to sit at his feet. Chirac would never have made a crack like that. Nor would he have chatted so openly after a session with his good friend Vladimir. Sarko is really different.’

‘REALLY DIFFERENT’ might also describe how Putin comes across to others, and – if they ever meet to compare notes – Blair and Sarkozy might certainly testify to that. He behaves in a way that will command the utmost attention from whomever he is with. As Vladimir Pribylovsky, the director of the political think tank Panorama, puts it: ‘In the West he tries to be Gorby. For the East he tries Stalin’s image. For pensioners he looks like the father of the nation. For young people he is a sportsman. For those who are Orthodox he is in church with a candle.’

Although he usually makes his point with a frankness that verges on rudeness, at times Putin can be deliberately indistinct and the court he has surrounded himself with tends to operate according to the old Russian village principle of ‘Ne vynosit’ sor iz izby’– which literary translates as ‘Do not carry rubbish out of the hut’, i.e. ‘Do not tell tales out of school’.

In recent years Putin has made obvious moves to improve his toughguy image outside of politics. In November 2010, wearing a patriotic helmet emblazoned with the Russian flag and Russia’s national symbol, a double-headed eagle, he drove a Renault Formula One car on a deserted stretch of road outside St Petersburg at speeds of up to 150mph. Photographers were on hand to record the stunt, as they were when he harpooned whales in the Arctic, dived in a miniature submarine almost a mile beneath the earth’s surface to the depths of Lake Baikal, piloted a jet fighter, rode a Harley Davidson with biker gangs, and took a long road trip across Russia’s far east at the wheel of a Lada.

He had previously posed for cameramen stripped to the waist, riding a horse through rugged terrain on one of his ventures into the Siberian region of Tuva. Wearing only green fatigue trousers and a hat similar to the one worn by Indiana Jones, his eyes hidden behind reflective sunglasses, he looked every inch the Hollywood player.

IN REALITY PUTIN seems to have no interest in image-building and does not give a second thought to the pop star following that has grown up around him. His supporters say ‘he is above all of that. He just gets on with his job’. They suggest that he is a superstar in the political firmament, but he does not bother paying attention to such things.