AND SO IT CAME to pass. On 24 September 2011 – exactly as the businessman with close personal ties to Vladimir Putin privately predicted in a London square six years earlier – Putin had accepted a nomination from his successor to be Russia’s President once again.

‘I think it would be correct for the congress to support the candidacy of the party chairman, Vladimir Putin, to the post of president of the country,’ said the sitting President, Dmitry Medvedev, at the ruling United Russia party’s annual congress. ‘For me this is a great honour,’ Putin responded.

There was something in it for Medvedev too, of course. He was to swap places with Putin and become Prime Minister after the presidential vote in March 2012.

As predicted yet again, a change in the constitution would mean that Putin’s first term back in the Kremlin would be for six years instead of four and he could serve a further six-year term, meaning he could stay in place until 2024. It would not be all be plain sailing – he warned of unpopular measures to cope with the global financial turmoil: ‘The task of the government is not only to pour honey into a cup, but sometimes to give bitter medicine’. But there would be good times, too: he was to be the man in charge of Russia for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi as well as the 2018 World Cup.

But can he really hang on until he is 72? Some outside Russia see this as a daunting prospect, but at home Vladimir Putin has established such respect within the grassroots that no alternative seems to be even on the most distant horizon, or indeed desired by the Russian people. In a 2007 interview with newspaper journalists from G8 countries Putin had spoken in favour of longer presidential terms in Russia, saying: ‘A term of five, six or even seven years in office would be entirely acceptable.’

For his part, Dmitry Medvedev was never keen to see his position as that of a temporary caretaker. But as a realist, he knew from the day he first became President that he could never outshine Vladimir Putin, however much he wished to make his own strong mark in Russian history with his proposals for radical reforms.

IF IT HAPPENS, 20 years as President would see Putin coming second only to Stalin, who served 31 years as Russia’s leader. But does he see himself carrying on where Stalin left off? Although he would most certainly wish to distance himself from Stalin’s worst excesses, there can be no doubt that Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin has studied the life and times of the man who, as General Secretary of the Communist Party, ruled his country for so long. ‘But don’t compare him with Stalin,’ said our businessman at a London restaurant during one of his frequent visits on matters Russian. ‘Stalin is the man who saved the Soviet Union, but although he and Putin had similar goals they had very different ways of achieving them.’

In June 2007 Putin organised a conference for history teachers to promote a high school teachers’ manual, A Modern History of Russia: 1945-2006, which portrays Stalin as a cruel but successful leader. Putin said at the conference that the manual would ‘help instil in young people a sense of pride in Russia’ and he pressed home the point that the human suffering caused by Stalin’s purges paled in comparison to the United States’ atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. At a memorial for Stalin’s victims, Putin said that while Russians should ‘keep alive the memory of tragedies of the past, we should focus on all that is best in the country’.

Putin’s understanding of Stalin’s modus operandi was rumored to cause a rift between him and Dmitri Medvedev in November 2010. Medvedev was insistent that his government should acknowledge that Stalin personally ordered the wartime massacre of 22,000 Poles by NKVD in the Katyn forest. Prime Minister Putin was rumoured to be against the admission, but Medvedev won and the government officially expressed ‘deep sympathy for the victims of this unjustified repression’ in 1940.

Putin sent a chill down many Western spines in the summer of 2007 by announcing the resumption on a permanent basis of long-distance patrol flights by Russia’s strategic bombers, which had been suspended since 1992. America’s official response to the threat of a new Cold War was almost mocking: ‘If Russia feels as though they want to take some of these old aircraft out of mothballs and get them flying again, that’s their decision,’ said US State Department spokesman Sean McCormack. In Moscow, McCormack’s statement was greeted with derision by the Air Force Chief General Zelenin, who said that in reality America shivered when the patrols were resumed; the Russian aircraft had in fact been considerably upgraded.

Putin’s announcement had been made during the SCO (the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation) summit in the shadow of Russian-Chinese military exercises – the first ever held on Russian territory – and the general consensus was that he was inclined to set up an anti-NATO block or the Asian version of OPEC. But when he was presented with the suggestion that Western observers were likening the SCO to a military organisation which would stand in opposition to NATO, Putin brushed it off with a bland lawyerly statement: ‘This kind of comparison is inappropriate in both form and substance’. He left it to his Chief of the General Staff, Yuri Baluyevsky, to expand on the comment. ‘There should be no talk of creating a military or political alliance or union of any kind [because] this would contradict the founding principles of the SCO,’ he said.

Putin continued on his course of subtle sabre-rattling by making the first visit by a Soviet or Russian leader to Iran since Stalin went there for the Tehran Conference in 1943. After a meeting with the country’s president, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, he held a press conference to declare that ‘all our [Caspian] states have a right to develop peaceful nuclear programmes without any restrictions’. It emerged only later that he had agreed with Ahmadinejad and the leaders of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan that none of them, under any circumstances, would let any third-party state use their territory as a base for aggression or military action against any other participant.

He stepped up the pressure on NATO by ordering Defence Minister Anatoly Serdyukov to send 11 ships, including the aircraft carrier Kuznetsov, into the Mediterranean for the first major sortie there since Soviet times. The ships were backed up by 47 aircraft, including strategic bombers, in what Serdyukov made clear was an effort to resume regular Russian navy patrols on the world’s oceans.

With the energy tool firmly in his grasp, Putin certainly does not need bombs or guns to wage war, but he had clearly set out to demonstrate that Russia still had military muscle in the unlikely event that it be required. Protest marches were organised by a civil front group called Other Russia, led by the former world chess champion Garry Kasparov and national-Bolshevist leader Eduard Limonov. In the subsequent demonstrations more than 150 people who attempted to break through police lines were arrested.

However, the marches received little support among the general public, according to popular polls. Indeed, the march in Samara held in May 2007 during the Russia-EU summit attracted more journalists providing coverage of the event than participants. When he was asked in what way the marches bothered him, Putin answered simply that such demonstrations ‘[should] not prevent other citizens from living a normal life’.

During the march in his home city of St Petersburg the protesters blocked traffic on Nevsky Prospect, much to the annoyance of local drivers. Putin telephoned his close friend, Governor Valentina Matviyenko, urging her to follow the softly-softly approach he had adopted in Moscow. Sure enough, her subsequent statement was a mild one: ‘It is important to give everyone the opportunity to criticise the authorities,’ she said, ‘but this should be done in a civilised fashion’.

Eventually Kasparov went too far and he was arrested on charges of public order offences as he led a march towards Pushkin Square. The arrest infuriated many and the President was obliged to deny that he was trampling on democracy; instead he accused the opposition – in this case Kasparov’s Other Russia – of trying to destabilise the country. But he kept a close enough eye on the proceedings to be able to point out that during his arrest the chess-playing dissenter was speaking English rather than Russian, suggesting that this clearly indicated Kasparov was targeting a Western audience rather than his own people. It lent weight to his assertion that some of his domestic critics were being funded and supported by foreign enemies who would prefer to see a weak Russia.

In his charge against Kasparov, Putin strayed off-message when he chose the moment to take a side-swipe at George Bush: ‘I do not want to offend anyone,’ he began, recalling the debacle of the 2000 US presidential election, ‘but let us recall that the election of the [then] President of the United States were associated with certain difficulties. The fate of the President was resolved in a court of justice rather than by direct plebiscite. In Russia the head of Russia is elected by secret ballot and in the US by an electoral college. As far as I remember, in the first case the college voted for a President who has less than half of the popular vote. Is this not a systematic problem in American electoral legislation?’

The events on Moscow’s streets inspired Boris Berezovsky to announce from his exile in the UK that he was plotting a revolution to overthrow Putin. In an interview with The Guardian Berezovsky said that Russia’s leadership could only be removed by force. After Putin’s spokesman Dmitri Peskov declared that Berezovsky’s remarks were being treated as a crime that would cause the British authorities to question the status of his asylum, the oligarch subsequently softened his words saying that he backed ‘bloodless change’ and did not support violence.

In a speech at a United Russia meeting in Luzhniki – widely interpreted as evidence that he advocated a one-party system – Putin declared: ‘Those who oppose us don’t want us to realise our plan... They need a weak, sickly state! They need a disorganised and disoriented society, a divided society, so that they can do their deeds behind its back and eat cake on our tab.’ The speech did nothing to assuage the critics, but then, it wasn’t intended to.

IN AN INTERVIEW with Interfax on 28 January 2008 Mikhail Gorbachev sharply criticised the state of Russia’s electoral system and called for ‘extensive reforms to a system that has secured power for President Vladimir V. Putin and the Kremlin’s inner circle’. It should have come as no surprise to Gorbachev that following his attack on the President, Putin ceased all contact with him. Gorbachev’s interview did not score him any points at home, but it did win him some dubious praise in the United States: the Washington Post observed in a leading article: ‘No wonder that Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union’s last leader, felt moved to speak out. “Something wrong is going on with our elections”, he told the Interfax agency. But it’s not only elections: in fact, the system that Mr. Gorbachev took apart is being meticulously reconstructed.’

Such criticism had little effect on the reigning President. Even when 10,000 people took part in an anti-Putin rally in Lyudmila’s home town, Kaliningrad, with protesters characterising him and his government as ‘corruptioners [sic] and liars’, and demanding resignations, including his own, the protests did nothing to sway the man himself off course. In reality, Putin pays little, if any, attention to the actions of dissidents. When he was asked about their marches, he simply shrugged his shoulders and said: ‘They don’t bother me’.

The leading man celebrated his birthday that autumn with longterm friends at the Chekhov restaurant in St Petersburg, a tourist haunt where the menu now includes ‘the President’s meal’ in memory of the occasion.

ONE OF HIS staunchest supporters assured me: ‘Despite enjoying the growing challenges of the job, I suspect he is growing tired of certain aspects of it, fed up with it even. He’s no Margaret Thatcher. Vladimir likes to enjoy himself, and that’s where guys like Abramovich, Berlusconi and Deripaska come in, because they go out and have fun. They have yachts and private planes. I think he pays private visits to a certain villa in Spain, but then he’s entitled to his time-off and he would never tolerate the kind of publicity that always seemed to surround Tony Blair on his holidays.’

Lyudmila Putina is obliged to tolerate Silvio Berlusconi’s often vulgar behaviour, but regards it as a small price to pay in return for the privacy his villa on the Mediterranean island of Sardinia affords Russia’s first family when they holiday there. But even Berlusconi knows that when his friend’s wife and daughters are in situ he has to keep his behaviour in check; Lyudmila has invested much of her life into raising two superb daughters, although she insists on sharing the credit with her husband: ‘Volodya said in his autobiography that he grew up in a loving atmosphere,’ she says. ‘I would add that he was raised with a strong work ethic and we try and instil this in our daughters. A child must be fully occupied in his or her spare time. For example, our daughters have been taught the violin since they were tiny. I also worried about the girls’ health and made sure that all the hard work didn’t take its toll on them. We never demanded that they got high marks at school. I consider that the main thing is knowledge.’

As if in a desperate bid to convince the world, Lyudmila went on to say how much her husband loved his daughters and always went to say goodnight to them even when he came home late.

On another occasion, however, Lyudmila lamented the fact that her husband had never been able to take as active a part in raising the girls as she would have liked. But she understood that he was busy doing the best for the development of democracy in the country, spending almost all his time and energy to unite Russia.

Nevertheless, Lyudmila – who says that she and Vladimir go to church together about once a month – added, ‘To me the President of Russia is first and foremost a husband’.

PUTIN WAS IN Beijing for the Olympic Games when, on the evening of 7 August 2008, he was informed that Georgia’s president, Mikhail Saakashvili, had embarked on an invasion of South Ossetia – one of his country’s two breakaway enclaves – going on to capture the southern half of the country, up to and including the suburbs of its capital Tskhinvali. Putin had warned the Russian people two years earlier that he suspected Georgian leaders of planning to settle their country’s territorial disputes by force, and as a mark of protest he had deported a number of known Georgian criminals in what provoked a bitter diplomatic row. But he had also carefully laid the plans for battle if his warning proved to be right.

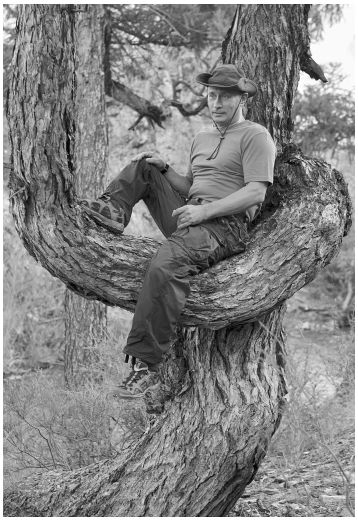

FOR THE Russian leader no holiday is complete without a photo opportunity. He sent this snap home from a vacation in Tuva.

Russia waited 36 hours before unleashing its full military might on the Georgian invaders. Even as Putin sat in the VIP box for the opening ceremony of the Olympic Games in Beijing, Russian tanks, soldiers and warplanes were surging south to engage with Saakashvili’s forces. At that point, according to the then Australian Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, seated two rows behind him in the Birds Nest Stadium, Putin found himself being castigated by the man in the seat next to him: George W.Bush, the very man, as it turned out, that Putin would blame for starting the war – albeit a brief one – that was to ensue.

Putin kept his cool. Even as the athletes paraded before him and Bush railed against him in the heart of the Chinese capital, Russian planes were already bombing a military base outside the Georgian capital of Tblisi.

Instead of returning to Moscow from Beijing, Putin flew to Vladikavkaz, the capital city of North Ossetia, Imperial Russia’s traditional staging post for campaigns in the Caucasus, and which neighbours South Ossetia, where the armed conflict was taking place. There he declared: ‘Georgia’s actions are criminal, whereas Russia’s actions are absolutely legitimate. The actions of the Georgian authorities in South Ossetia are obviously a crime. It is a crime against its own people, first and foremost.’ And while his soldiers fought just across the border, Putin added: ‘A deadly blow has been struck against the territorial integrity of Georgia itself, which implies huge damage to its state structure. The aggression has resulted in numerous victims, including among civilians, and has virtually led to a humanitarian catastrophe, but time will pass and the people of Georgia will give their objective judgments on the actions of the incumbent administration.’

Putin was to claim that, since he was in China at the time the order was given, it was President Medvedev who had taken the decision to attack.

Finally he went home to Moscow for a pow-wow with Medvedev, who had never left the Kremlin throughout the crisis. In all, 10,000 Russian soldiers and their tanks crossed the border into Georgia, bombers and fighter jets flew regular sorties and ships of the Russian navy were deployed menacingly off the Georgian Black Sea Coast; this was not the work of the newer Kremlin occupant. As his mentor Anatoly Sobchak had once said of Putin: ‘He is as tough as nails and sees his decisions through to the end’. In any event, the Russian forces stopped short of reaching Tbilisi; their presence in the country was enough and it was all over in two days.

Back in the White House, Bush summoned reporters to the Rose Garden and called on Putin – the man whose eyes he had once looked into and ‘seen his soul’ – to announce an immediate ceasefire, recalling his troops from the conflict zone: ‘Russia has invaded a sovereign neighbouring state and threatens a democratic government elected by its people. Such an action is unacceptable in the 21st century,’ he said.

Meanwhile, in Moscow, Putin’s men were displaying evidence to support Putin’s theory that America had orchestrated Georgia’s invasion of the tiny independent republic. The Russian Deputy Chief of Staff, Colonel General Anatoly Nogovitsyn, showed off a colour copy of what he said was a US passport for a Texan named Michael Lee White, which had been found in the basement of a house in a South Ossetian village among items that belonged to the Georgian attackers.

Putin hardly needed any evidence. He was sufficiently sure of himself to press on and, in response to Bush’s harsh criticism, he racked up the tension by saying that Russia had hoped the US would restrain Georgia – a country with which it had such special ties that even the main road to Tbilisi airport was known as George Bush Boulevard. ‘The American side in fact armed and trained the Georgian army,’ he said. ‘Why hold years of difficult talks and seek complex compromise solutions in interethnic conflicts? It’s easier to arm one side and push it into the murder of the other side, and it’s over.’ Later he added: ‘We have serious grounds to think that there were US citizens right in the combat zone. And if that’s so, if that is confirmed, it’s very bad. It’s very dangerous.’

Ignoring a ceasefire pledge by the Georgian president Mikhail Saakashvili, Putin had ordered tanks and armoured vehicles to keep going. After days of fighting the Russian soldiers had seized a military base and four cities, while Saakashvili was still calling for an emergency meeting of the UN Security Council.

After mediation by the French presidency of the European Union, the parties reached a preliminary ceasefire agreement on 12 August, signed by Georgia three days later and by Russia on 16 August; but fighting did not stop immediately and, after signing the agreement, Russia pulled most of its troops out of Georgia, but left others to establish buffer zones and create checkpoints within Georgia’s interior which were to remain until the following October. On 26 August Russia recognised the independence of South Ossetia, but America still grumbled that Georgia had lost some of its territories.

Three weeks later, as Medvedev did his best to look masterful addressing Russia’s Security Council about the Georgian crisis, Putin returned to the area, suitably adorned for the jungle setting in combat boots and camouflage fatigues, and accompanied by a TV camera crew. In the bizarre event, the President saved the crew by firing a tranquilliser dart at a tiger which was charging towards them. Showing how happy he was that the crew had been saved, and that the tiger would live, the normally serious Putin rewarded them with a rare triumphant smile.

‘At least,’ a man in the Kremlin Press Office said to me two days later, ‘it wasn’t like [Leonid] Brezhnev. He liked hunting bears and wild boar, but he got so sick towards the end, they had to drug the animals and tie them to trees so he couldn’t miss’.

The good humour Putin displayed on his jungle mission did not last. One month after the conflict, during a three-hour lunch for some of the world’s leading Russia-watchers under the restored dome of a former sanatorium in Sochi, he turned the air blue with his defence of his country’s much-criticised actions: ‘Russia had no choice. They [the Georgians] attacked South Ossetia with missiles, tanks, heavy artillery and ground troops. What were we to do?’ If his country had not invaded, he said, it would have been like Russia ‘getting a bloody nose and hanging its head down’.

Then he went for his media audience. ‘What did you expect us to do? Respond with a catapult? We punched the aggressor in the face as all the military text books prescribe.’

While his guests chewed their smoked duck and sipped nervously on their wine, Putin prodded a finger and chastised them for staying silent when the Georgian invasion began. And he was not finished: he accused George Bush of acting like ‘a Roman emperor’ and warned Poland and the Czech Republic against hosting US missiles.

Warming to his theme, he went on: ‘If my guesses are confirmed, then that raises the suspicion that somebody in the United States purposefully created this conflict with the aim of aggravating the situation and creating an advantage for one of the candidates in the [forthcoming] battle for the post of US president,’ he said. Later still, he became more specific, suggesting that Bush’s verbal attack on him had been ‘cooked up in Washington to create a neo-Cold War climate that would strengthen Republican candidate John McCain’s bid for the White House’.

The chief diplomatic adviser to Nicolas Sarkozy, Jean-David Levitte, revealed later that when the Russian tanks were just 30 miles from Tblisi, on 12 August, Putin told the French President (who was in Moscow trying to broker a ceasefire) ‘I am going to hang Saakashvili by the balls’.

Sarkozy thought he had misheard. ‘Hang him?’ he asked. ‘Why not?’ Putin replied. ‘The Americans hanged Saddam Hussein.’ Sarkozy tried to reason with him: ‘Yes, but do you want to end up like Bush?’ Putin who, for once, was briefly lost for words, responded: ‘Ah, you have scored a point there’.

The whole tone of Putin’s outburst served to further underline the belief that he was calling the shots in Moscow and not Medvedev, who was Sarkozy’s official host at the Kremlin meeting. The language was in keeping with his fondness for coarse imagery: in 1999 he had vowed to chase down Chechen terrorists wherever they were — ‘if we get them in a toilet – pardon me – we’ll rub them out, even in the outhouse,’ he declared.

PUTIN and Archimandrite Tikhon Shevkunov, head of the Sretensky Monastery, laying flowers at the tombs of the anti-Bolshevik White Guard commanders Denikin and Kappel, and the emigré philosopher Ilyin at the Donskoy Monastery.

THE GEORGIAN EPISODE severely strained relations between the Russian government and Her Majesty’s Ambassador to Moscow. Never one to mince his words, Sir Anthony Brenton said in September 2008: ‘I think we’re in quite a dangerous moment now, because we have seen an upsurge of anti-Russianism in the West and an upsurge of anti-Western feelings here in Russia. There is a real danger of political confrontations of one sort or another. I think it is really important that we get those sort of events under control... We have serious disagreements – not least about Georgia – but we need to be able to resolve these in an atmosphere which recognises the very important shared interests we have.’

Cambridge-educated Sir Anthony, who had taken up his post in 2005, had been caught up in flash mob acts orchestrated by the youth group Nashi – nicknamed the Young Putinists – who gathered outside his official residence and chased him around Moscow even when he was out shopping: ‘I think it was a deplorable manifestation even by Nashi [standards], an insult not only to me but to the United Kingdom. It was unpleasant for my family. We had [the Young Putinists] outside the house from early in the morning.’

But it wasn’t only the Nashi who persecuted the Ambassador and his family. An embassy source who had bravely agreed to meet me for coffee at the closely-observed Sovietsky Hotel admitted: ‘Things have got pretty bad, what with the row over them refusing to extradite Andrei Lugovoy, the forced closure of British Council offices, the row over BPTNK and now the standoff over Georgia, it’s made life pretty unpleasant here for us Brits; they seem to think we’re all spies again. They’ve definitely stepped up the bugging, the eavesdropping.

‘It’s explosive. I don’t know how Sir Anthony has been able to stand it. Did you know they chased his Range Rover through the streets of Moscow at high speed one night? We’ve been getting signals for some time now that their Foreign Ministry wanted him out of the country and if they can do that to Bob Dudley [the chief executive of BP-TNK] who’s to say they didn’t cause Sir Anthony’s departure? He’s going any day.

‘I think the British Government’s stand over Georgia was the last straw for Putin. That really rattled his cage.’

IT WOULD BE wrong to conclude from such an episode that there is widespread anglophobia in Russia; on the contrary, there is considerable empathy towards Britain and its culture. Following the 7 July terrorist bombings in London in 2005, the Russian public offered condolences to the UK. People carried flowers to the British Embassy in Moscow and the general mood was clearly on the side of the victims. Putin himself condemned the attacks, declaring: ‘All civilised countries should unite in the fight against international terrorism’.

BY THE END OF 2008 Putin’s intolerance of those who procrastinate had become even more apparent when Russia found itself involved in yet another international dispute, this time with Ukraine over the latter’s gas debts. The previous March (2008) he had ordered Gazprom to reduce supplies to Ukraine because it was not paying its bills. This affected 18 European countries, who reported major falls or cutoffs of supplies of Russian gas transported through Ukraine.

Some 80 per cent of Russian gas headed for the EU passed through pipelines in Ukraine territory, a service for which Ukraine received 17 billion cubic meters of the product in payment for the corridor facility it provided. That still left Ukraine with a bill for six to eight billion cubic meters to meet its domestic needs, and it was not paying up. Putin accused the Ukrainians of stealing Russia’s gas by siphoning off large quantities from the pipelines, and he demanded the country hand over the complete infrastructure in payment for its debts.

Europe’s urgent cry for the two countries to resolve their differences endorses the statement made to me by his businessman friend the previous year that Putin’s huge control over natural resources could bring much of the world to its knees ‘without firing a shell or a bullet’. This has nothing to do with diplomacy, he simply knows the strength of his country and therefore his own strength, and is not afraid to employ both. But Ukraine had a strong bargaining card: since so much of Russia’s mighty Gazprom revenues came from gas pumped across its territory Putin might be able to exert pressure when Europe shivered but a total shutdown would cost his economy dearly and that he simply could not afford. So in November 2009 he flew to the Crimean resort city of Yalta to forge a new agreement with Ukraine’s Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko. Russia would lift penalties it had intended to impose on its neighbour; transit fees paid by Gazprom would be increased by 60 percent, and the price of gas supplied to Ms Tymoshenko’s country would be pegged to market rates for the first time.

The Ukrainians had bowed their heads in submission. Europe breathed a sigh of relief. Putin had demonstrated once again that actions speak louder than images.

In the midst of the Ukraine gas crisis, Putin had to deal with questions about whether or not he had paid £20,000 for a private performance by a London-based band which impersonates the Swedish superstar group, Abba. Bjorn Again’s manager, Rod Stephen, said that the band had been flown to Moscow then driven 200 miles north by bus to a remote location near Lake Valdai, where they were accommodated at a military barracks. It was only as they prepared to perform in a tiny nearby theatre the following night that they apparently learned who they were supposed to be entertaining. Aileen McLaughlin, who impersonates Abba’s famed blonde Agnetha Faltskog, claimed that Putin and a woman companion were sitting on a sofa veiled by a lace curtain and that they and six others clapped along as they sang their versions of Waterloo, Gimme Gimme Gimme and Dancing Queen. They said they were not invited to meet their smallest ever audience, but were driven straight back to the barracks after giving the performance.

Although this was probably no more than a publicity stunt by the band, the Prime Minister’s spokesman was obliged to distract himself from the Ukraine crisis in order to deny that Putin had been anywhere near a group of Abba impersonators. It would certainly not have done much for the Prime Minister’s street cred: perhaps unwisely, Dmitri Medvedev had been at pains to let it be known that he favoured the heavy metal band Deep Purple.

Although Putin himself may have been seen to be gliding across the waters with relatively little effort, a PR machine was all along operating below the surface at desperate speed, attempting to change the Russian people’s view of their leader. Those managing it, however, were as inexperienced in their task as Putin had been in his when great office was thrust upon him. Relatively early in his presidency a pop record was sent to Russian radio stations by an anonymous source. Supposedly by an allgirl group Singing Together, the song was called Takogo kak Putin (Someone like Putin), and the general idea of the incredibly crass lyrics was that the girls’ regular boyfriends ‘get stoned, have too many fights and don’t look after us properly’:

I want a man like Putin who’s full of strength

I want a man like Putin who won’t be drunk

I want a man like Putin who won’t hurt me

I want a man like Putin who won’t run away

The record was well – indeed expensively – produced and with so much airplay the tune caught on with its young target audience, but no one was able to buy it, since it never appeared in the shops. Other politicians envied Putin the popularity it reflected, but the Kremlin disowned it.

Similarly, a Vladimir Putin fan club, posting its address as The Kremlin, Red Square, Moscow, declared that it stood for ‘A strong Russia; centralised government (because Russia cannot survive as a decentralised state), the reunification of traditional Slavic and Orthodox lands such as Ukraine and Belorussia that were stolen by clandestine groups and Western powers’ and ‘the imprisonment of all oligarchs who robbed Russia’. On the day he stepped down from the presidency, his ‘fan club’ posted a notice hailing him as ‘the man who made Russia enter the century as a superpower once more’.

The notice concluded: ‘Our group will not change its name nor will it change its principle. We will always be loyal to the path that Putin has chosen, a path that, instead of being dictated by liberalism, socialism or any other -ism, is chosen only in the best interest, irrespective of what -ism it has to be against or follow. For that we thank Vladimir Putin for eight amazing years. We wish him good health and a long life.’

Though he may never even have been aware of the fan club, Putin`s relatively young and virile image was especially welcome after the sickly Yeltsin years. Remember, he had dived to the bottom of the world’s deepest lake, Lake Baikal, in a mini-submarine, attached a tracking device to a white whale (warning it not to be ‘naughty’ as he went) at a research centre and, during President Obama’s visit to Moscow, he stole the limelight by joining a group of Hell’s Angels-style bikers called the Night Wolves. Dressed all in black and wearing shades, he even boasted that he had performed a wheelie.

PUTIN IN OCTOBER 2010 Putin’s PR spinners were back at work. They persuaded him – and I’m told he took a lot of persuading – that since his family-man image had taken a battering from whispering campaigns about his fondness for beautiful young women in general, and claims that he was going to marry the gymnast Alina Kabaeva in particular, he should take part in an ‘at home’ video with his wife and daughters. The result was a ham-fisted 11-minute film which was posted on the Government’s website. He appeared awkward and rarely met Lyudmila’s gaze but concentrated his attention on the couple’s black Labrador, Connie. For her part Lyudmila looked nervous and drawn according to The Times. Furthermore, she was not wearing her wedding ring. Russian women switch their wedding ring to their left hand if they are divorced or widowed and Mrs Putin had previously been seen wearing a gold ring on her left hand, although it has never been established whether or not it was her wedding ring.

The obliging Mr Peskov stated that it was ‘not obligatory’ for her to wear a wedding ring. ‘It is not because they are not married,’ he concluded to the surprise of everyone, including the Putins.

Quite how much the couple love each other is impossible to establish but there can be no doubt about the unprecedented affection the Russian people have for their leader. Indeed, having been such a popular president, Vladimir Putin was always going to be a hard act to follow. Throughout his term in the office, Dmitri Medvedev was taunted by claims on some occasions that he was Putin’s puppet and on others that he and his Prime Minister were constantly at loggerheads. One of those who would have liked to divide and rule the two men was Moscow’s mayor, Yury Luzhkov. He made it clear that when it came time to nominate the next President he would back Putin, but his disrespect for the sitting president cost him dear – precisely, his job. Luzhkov had written an article in the official government newspaper Rossiiskaya Gazeta challenging Medvedev’s decision to suspend construction of a motorway from Moscow to St Petersburg – a project Putin had been known to favour.

But if the mayor – who controlled a budget of more than $30 billion and a city that was responsible for almost 29% of Russia’s gross domestic product – sought to drive a wedge between Putin and the man he put into the Kremlin, then he failed miserably. Early on the morning of Tuesday 28 September 2010, an emissary arrived at Luzhkov’s office to inform him that he had been fired. And if he expected Putin – whom he had constantly derided during his term as President – to rush to his assistance, then he was to be sorely disappointed. After conferring faint praise on him – ‘to a certain degree [he has been] a symbolic figure of modern Russia’ – Putin went on: ‘It is evident that relations between the Moscow Mayor and the President soured. The Mayor is the President’s subordinate and not vice versa, so [Luzhkov] should have taken the steps required to normalise the situation.’

They may have disagreed over Stalin’s position in history, but no one in Moscow doubts that Putin and Medvedev were wholly in accord when it came to removing the city’s most powerful man, the mayor whose wife rose to become one of Russia’s three richest women.

MY FIRST VISIT to Dmitri Peskov’s Kremlin office proved to be more dramatic than I could ever have imagined. It was bitterly cold on the night of 1 November 2006 and older Muscovites, swathed in huge overcoats, their heads wrapped in fake fur hats, were hurrying in all directions to get home; in stark contrast, brightly clad youngsters were heading for a multi-storey underground shopping mall offering franchises of Benetton, Diesel and Top Shop, electrical stores selling wide-screen television sets and washing machines, cappuccino bars and mobile phone shops, a McDonald’s, an Irish pub and a travel agency offering holidays in Spain, Turkey and Egypt, where menus nowadays are available in Russian. It all constituted an outward and visible sign of Putin’s economic success, for by this time the average wage was up by 13 per cent year-on-year to $415 – still low, but four times what it was when he became President – and consumer credit had mushroomed from zero to $40 billion. Even some of the oil, gas and metal oligarchs had been obliged to spread their entrepreneurial wings and diversify into the consumer market.

The mall behind me stood as a symbol of Westernisation just a stone’s throw from the imposing set of buildings ahead of me, which housed the presidential headquarters.

Wearing a trilby hat lent to me by Putin’s businessman friend (I had underestimated the need for headgear in this inhospitable climate), I reached the base of the enormously wide and high steps that lead to Red Square 10 minutes ahead of the meeting scheduled by the President’s spin doctor, only to find that armed soldiers standing shoulder-toshoulder were totally blocking access to Moscow’s oldest and most famous square. I attempted to ask one to let me through, explaining that I had an appointment to keep. But I couldn’t speak his language and he couldn’t understand mine. He pushed me back with the arm that was wrapped around his Kalashnikov.

In desperation I phoned a Russian friend and explained the situation. He told me to hand my cell phone to the soldier so that he could apprise him of the ‘importance’ of my mission. Reluctantly the solider took my phone and whatever it was my friend said to him worked, for after a brief conversation the soldier stood aside for just a few seconds and with a contemptuous twitch of his head nodded me through.

Shivering from the cold, I climbed the steps, only to find when I reached the top and peered through the Resurrection Gate that the whole square ahead of me, which would normally be filled with tourists even at this hour, was in pitch darkness. In the distance I could make out the silhouette of the onion-shaped domes of St Basil’s Cathedral, built in the 16th century by Ivan the Terrible. But that was about all. Picking my way carefully, I knew that to my right was the mausoleum housing the embalmed body of Lenin and to my left should be the GUM department store, normally brightly lit and bustling with its nouveau riche contingent of well-heeled shoppers. But tonight it was bathed in silence and an eerie darkness, its elegant steel framework and glass roof that blend surprisingly well with the medieval ecclesiastical architecture of its earlier construction, well hidden.

Then, suddenly, everything changed. Red Square was lit with a dazzling display of spotlights and silence was punctured by the deafening sound of military band music. It was then I realised that I was far from alone. In fact I was surrounded by hundreds of grey-coated soldiers who began to march in that menacing way those Russian soldiers do so well.

Now here was a problem: their four-abreast line stretched unbroken around the square. I had to get through that line to reach the Kremlin’s ‘business’ entrance in the far right corner. It was a tricky manoeuvre but, seizing my opportunity when I spotted a small gap in the marching line, I managed it. Alas, that was not the end of the ordeal. Once through the entrance I encountered the strictest of security checks and found myself being searched, patted down and deprived of anything metal including my buckled belt and, alas, my precious tape recorder: thank God they did not take my note book. Even my overcoat was held in a cloakroom where, ominously, I spotted no others. Then a silent guard escorted me to an elevator and took me to an upper floor, where the doors opened onto a totally different sight: a wide, splendidly decorated arched corridor that was brightly lit and overheated. I fell into step beside the silent guard, who virtually marched me to an open door.

‘Mr ’Utchins’ he announced to Mila, the attractive secretary seated behind the desk. She stood up and welcomed me with a smile and an introduction in perfect English. Politely she explained that her boss had been delayed in a previous meeting, but as much as I tried to edge her towards the subject of Vladimir Putin, she steered the conversation round to Roman Abramovich, whose biography I had just written with Dominic Midgley. ‘What’s he like?’ she persisted. ‘I’m so interested in what he is doing in the UK.’ Then the telephone rang and she spoke in her native tongue to someone I assumed was to be my host for the next hour.

Moments later a side door opened and there stood the tall, slim, beaming figure of Dmitri Peskov, Deputy Press Secretary to the President of the Russian Federation. With his reddish hair somewhat wild and sporting a thick moustache, he looked more like a fun-loving university graduate – despite the fact that he was 42 at the time – than the man who is the buffer between the international media and one of the most powerful men in the world.

Cordially he invited me to ‘step inside’, indicating the large room that is his office, crammed with the paraphernalia of a man with a restless mind. At one end books were piled high on a table, which was also used to display framed photographs; at the other a cosy fireplace with an armchair on either side. I was directed to one of the chairs and he took the other. Would I like coffee or Georgian tea? Like my host, I chose the latter and while we waited for its delivery I told him about my dilemma in the square outside. He laughed: ‘Oh, that’ll be the rehearsals for tomorrow’s parade,’ he explained. ‘I should have warned you.’

WHEN he was asked about his friendship with Vladimir Putin, Archimandrite Tikhon (above) asked ‘What are you trying to make out of me, some sort of Cardinal Richelieu?’

And then the tea arrived, served in porcelain cups and with biscuits. So this was how the media could be charmed in Putin’s Russia, I pondered. It could not have been like it in the days of Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev. Or could it?

As we ate cake and drank our tea by the fireside, I asked Peskov how would Vladimir Putin – the man raised in a cramped room with a peeling ceiling, who had been welcomed to London on a state visit, who had seduced an American president with his stunning blue eyes, a British Prime Minister with his good manners, the leader of Italy with his frequent fun-filled visits to the Riviera, and the French President with the Grand Cross of the Légion d’Honneur – like to be remembered?

Peskov shrugged his shoulders and replied: ‘It doesn’t matter to him. He lives in the now. What happens after he is gone is of no concern to him. As long as he gets home, whatever the hour, has his bowl of kasha [a kind of porridge] and perhaps a cup of tea to wash it down, he’s happy.’ I put to him what the businessman had said to me: ‘He gets angry, you can always see it when he’s angry on TV’. Peskov’s comment was: ‘Yes, he can get angry, but I’ve never seen him driven into a rage, he has impeccable self-control. Little things can trip him up, though. He likes going to church, but he hates it when there are photographers there taking his picture. That’s understandable. Certain situations deserve privacy, respect.’

NEVERTHELESS, WHAT Peskov had to say – and in particular his guidance on matters of political importance dealt with elsewhere in this book – all seemed highly believable, with one exception. As I trudged back through the snow to my hotel that bitterly cold night, one thing he’d said puzzled me: did he mean that Putin really had no desire to leave anything to be remembered by, that he lives in the day? Surely no man with such greatness thrust upon him could possibly operate without a keen eye on the future? Putin’s supporters insist that he thinks foremost of Russia’s future, a true believer in the sentiment that you cannot live for the day. ‘He believes that Russia’s tomorrow always begins today’, they insist.

Or did he perhaps mean Putin was not interested in personal glory? After all, I had by now been made aware of a town positioned more than a thousand miles east of Moscow. Deep inside Siberia, Khanty-Mansiysk is Putin’s secret legacy. It is his equivalent of Poundbury, the model town in the English county of Dorset created by Prince Charles as his ideal for the future.

Khanty-Mansiysk is located in the heart of Yugra, Russia’s richest region, providing 58 per cent of the country’s oil. Putin installed his close friend Alexander Filipenko as the region’s governor* and found a way to allow Yugra to keep a substantial amount of the oil revenue in order to provide comfort and facilities for its citizens which were to be the envy of the rest of the population – or would be if many of them knew about it. Those who lived away from Russia’s main cities in the ‘donor regions’ always had to pay more in taxes than they received in the annual budgets to maintain the social sphere in their communities, and there’s no denying this had increased under Putin – except, that is, in Ugra.

I journeyed across western Siberia to interview Filipenko for this book and to see Putin’s dream for myself. The region was once one to which the Soviet Union dispatched its dissidents and most hardened criminals – usually to die from the bitter cold in winter, sweltering heat in summer or the total lack of medical facilities. Today that has all changed thanks to the oil riches, which provide heating and airconditioning in abundance and an ultra-modern hospital. It is no coincidence that most of the splendid homes in Khanty-Mansiysk (where the crime rate is virtually zero and Russia’s chronic incidence of alcoholism is hardly noticeable) are no older than Putin’s period in power. Even the Russian film festival is staged there in the most amazing theatre east of the capital. One of Putin’s last acts as President was to switch the 2008 Russia-EU summit from Moscow (to the dismay of the capital’s mayor Yuri Luzhkov) to Khanty-Mansiysk, so that he could show off his dream town to other world leaders.

Perhaps he sees it as a ‘soft’ ideal, but Putin’s Siberian project is not one that welcomes publicity. After I left I learned that Governor Filipenko had received a call from Moscow: The Interior Minister wanted to know why he had received me there, what I had asked and what I had been told. In the eyes of the Kremlin, both the Governor and I had apparently broken the rules. This view was endorsed a few days later when I received an uncharacteristically angry call from the friend Putin and I have in common, wanting to know what I had been doing in Khanty-Mansiysk in the first place.

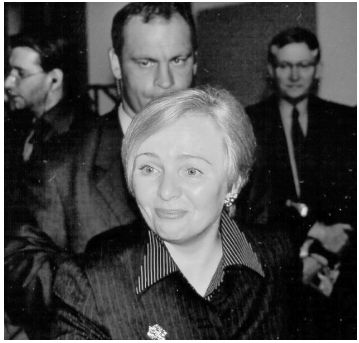

LYUDMILA Putina in Canada, December 2000

© Alexander Korobko

IN WRITING THIS biography of Vladimir Putin I was presented with numerous negative opinions, many of which seemed well-founded on first hearing. But, having spent years studying every aspect of his public and personal life, it seems impossible to reach any other conclusion than that Putin has been Russia’s saviour. When he was suddenly catapulted into high office in 2000 the country was not just in bad shape, it was falling apart. The signing of the Khasavyurt agreement could have meant the beginning of the break-up of Russia, for within the agreement there was a point about the possibility of Chechnya leaving the Russia Federation, which would inevitably have led to a domino effect. Crime levels were frighteningly high: this was brought home to me when I encountered a young Moscow woman who, in a short space of time before Putin came to power, had seen another like her shot in the head in the courtyard of the apartment block they both called home. Not far away she had witnessed a man blown up in his car as he left a smart restaurant. The first victim was an estate agent who had got caught between two antagonists in a relatively small property deal; no one knew what offence the second had caused. My informant did not live in a rundown suburb, but a smart residential area just 10 minutes’ walk from the Kremlin. Of course there are still murders on Russian streets, as there are in towns and cities throughout the world, but journalists and authors are not singled out any more than estate agents or restaurant customers.

Make no mistake, the world’s biggest country was in chaos as the Soviet system lived out its dying days. Boris Yeltsin gave the country freedom when he tore up his Communist Party membership card and became the first President of the Russian Federation in 1991, but under his inept leadership the chaos only worsened. Experts thought it would take three decades to get things right, but Putin did it in less than one. Yes, there has been a price to pay. Russians have fewer political rights today, but most seem to consider that a fair price to pay for the restoration of law and order. Almost one in three heads of cities and small towns is now serving a sentence in cases not far removed from corruption and other breaches of the law, while the collection rate of taxes in the oil industry has increased 15-fold.

The war in Chechnya has been halted and the activities of terrorists have been considerably reduced, to a fraction of what they were when the second President of the Russian Federation first came to power.

DESPITE HIS OWN dismissal of a grand epitaph, Putin will perhaps be best remembered for restoring Russia’s national pride and – in his later period as Prime Minister – the establishment of open government. He has enjoyed rather less success to date in the war he has waged against corruption, which has for generations permeated its stench through public life, but he’s working on it: when recently a man complained about the harm such corruption was doing to the country’s military services, Putin personally ordered a thorough investigation of his complaint. ‘If he is simply being mischievous then punish him,’ was the message conveyed to the person he ordered to carry out the investigation. ‘If not, then put right what he tells us is wrong.’

Russia has undoubtedly changed under Putin, but has he changed? ‘Certainly,’ says someone who has observed him in close quarters since the very early 90s. ‘He was always self-confident but these days he lets it show. He has fun, he enjoys his popularity, in fact he enjoys life and I don’t think you could have said that about him in times gone by. Nevertheless I believe it was always in his DNA. He is a most remarkable man and if DNA had been discovered when he was a boy I believe they could have told us all what an interesting man he was going to be, what an amazing life he was going to lead.’

Perhaps too much has been made of comparing him with Josef Stalin. As pointed out earlier in this chapter, Putin studied in great detail the man who once held his job, but the leader he really draws inspiration from is Pyotr Stolypin, born 150 years ago. Like Putin, Stolypin became Prime Minister at a truly dramatic period in Russian history, a time of great political and social turmoil. Constantly repeating his mantra, ‘You want great upheavals, but we want a Great Russia’, Stolypin fought hard and successfully to achieve peaceful reform when all around him were advocating revolution. Whereas Stalin wanted to shut the West out, Putin clearly wants Russia to be up there on the world stage, just as Stolypin did. Having dug deep into his own pockets to make a substantial contribution towards a Moscow monument to Stolypin, Putin subsequently solicited similar personal subscriptions from members of his government. He may well hope that one day his successors will do the same for him. Certainly, his re-election as President of the Russian Federation will mean he has plenty of time in which to continue wooing his countrymen, though if he is to finish the great task that Stolypin started there isn’t a moment to lose. For it is not just at home that Putin has to prove himself. Republican Presidential candidate Mitt Romney asserts that America is ‘an exceptional country with a unique destiny and role in the world’. As Russia is also one of the five permanent members in the UN Security Council, it has enough kudos to make similar statements and Putin may now be rethinking some of his earlier isolationist views, such as the one he expressed in 2007 when he said: ‘I do not think that we should take some kind of missionary role upon ourselves... I therefore have no wish to see our people, and even less our leadership, seized by missionary ideas.’

We should remember the words of Dostoevsky, who put the challenge succinctly when he said: ‘the destiny of a Russian is pan-European and universal... To become a true Russian, to become a Russian fully, means only to become the brother of all men, to become, if you will, a universal man’. If Putin’s destiny is to become such a man, then we’ll see the emergence of a new Russia, one with the moral right to call itself truly pan-European and universal.