Bruce Gyngell during his ‘staged’ welcome-to-television address.

Let’s start on 13 July 1956, in Bell’s Hotel, Woolloomooloo, just near Sydney Harbour. A group of drinkers are gathered around the bar and it would be fair to say they are in a world of wonder that transcends even the alcoholic content of their glasses. These bar flies are watching the first-ever television test transmission in Australian history, as Channel 9, Sydney, experimentally flaps its broadcasting wings.

Three days later, in Melbourne, HSV-7 technicians would cheer as the first-ever signal successfully found its way from the South Melbourne station to Seven’s Mount Dandenong receiver and back. Dick Jones was enjoying his first day as a techo in TV and wondered what all the fuss was about. Shortly after, images of a child standing at the Melbourne Shrine of Remembrance would be successfully screened. These technical baby steps all took place less than four months before three Melbourne start-ups planned to cover an Olympic Games.

You have to remember that this was only 27 years after audiences had heard Al Jolson singing in The Jazz Singer and marvelled at sound being added to motion pictures at the theatre. In other words, iPods were a long way away. In 1956, there was no such thing as videotape. If you wanted to tape something, you had to point a 16 mm camera at a blue image of the TV screen received directly from the studio camera. Sound was recorded separately, and had to be matched to the video later.

This is why there is no original footage of the day Australian television began. Bruce Gyngell was the man who famously said: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, good evening and welcome to television’ at 6.30 pm on TCN-9 on 16 September 1956. He had enough sense of theatre to secretly recreate the moment three years later, when there was a way of filming it for history, but the real thing was transmitted to a few thousand television sets around Sydney, and then disappeared into the ether.

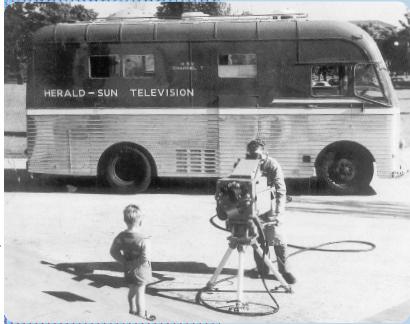

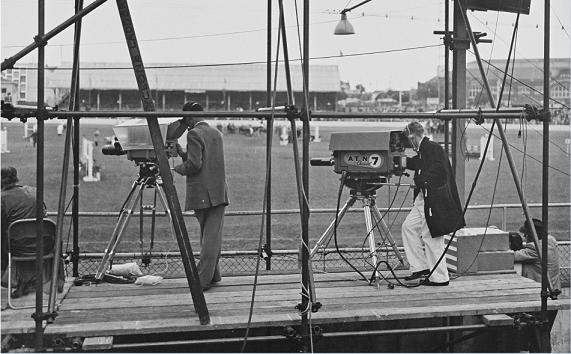

An early Channel 7 Outside Broadcast (OB) van.

If we could see that historic moment, the first thing we might wonder is why it’s shot at such a strange angle. That was because the Nine studios were still under construction (these were only the beginning of regular, freely available test transmissions – the official launch of the station was still more than a month away) and were not ready for the big night, so Gyngell was forced to deliver his line from an engineering storeroom so small the massive camera could barely fit inside the door. Nine was so desperate to be ‘first’ that such incidentals as a lack of studios simply could not get in the way.

All of which is a long way from mid-1954, poolside at the home of Consolidated Press newspaper tycoon Frank Packer. If ever you wanted a pure display of what makes a media mogul tick, then this is the date to revisit.

After a long and weighty Royal Commission into all matters to do with this newfangled idea of television, which had started on 23 February 1953 and ran for the rest of that year with evidence hearings in most states, Prime Minister Robert Menzies finally announced that bids would be taken for two commercial licences to run stations in Melbourne and Sydney, alongside the government’s own intended service, a television version of the Australian Broadcasting Commission.

Around this time, a young radio broadcaster, 24-year-old Bruce Gyngell, was lounging in the sunshine, enjoying a pool party at the home of his mate, Clyde Packer, son of Frank.

‘Frank Packer came up to me and said, “Oh, you’re that announcer fellow, aren’t you? I’m applying for a television licence, which I’ll probably get, so maybe I’ll need people with radio experience,”’ Gyngell recalled in an interview years later. Two things stand out in that remembered conversation. Frank’s casual confidence – ‘which I’ll probably get’ – and the fact that his immediate reaction was that he’d need some radio talent.

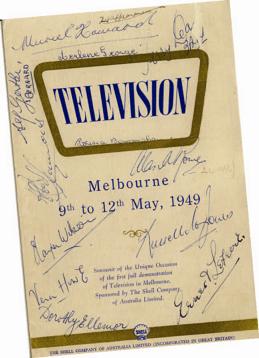

More than seven years before TV officially began, the Shell Company sponsored several demonstrations of the new medium in Australia.

Those involved in the start-up of Packer’s television company never had any doubt about their employer’s motivation. It was not so much about being a visionary – of Frank Packer somehow seeing the glorious and profitable television empire just waiting to unfold. It was about pure fear that television might somehow eat into the company’s newspaper profits. So, better to keep the enemy close.

It says a lot about politicians, then and now, that the introduction of television came only after a Canberra-based Royal Commission had fussed and worried over the issue. Professor G.W. Paton, vice-chancellor of Melbourne University, was the chairman, while other members included Mr R.G. Osborne, chairman of the Australian Broadcasting Control Board, Colin Bednall, then a newspaper executive (and later a central figure at GTV-9), and Mrs Maude Foxton, President of the Western Australian branch of the Country Women’s Association. Throughout 1953, they listened to 122 witnesses and eventually turned out a 251-page report.

Who knows what the alleged ‘witnesses’ actually had to say, though. Speak to anybody involved in those heady days of discovery and onward into the later fifties and the overriding theme is that nobody had a clue what television was about. In fact, like a sportsman with bad technique, those attempting to drive the new medium had to first lose the bad habit of believing it would be ‘radio with pictures’ before they could truly understand what they were trying to create.

Technically, television had been a long time coming. The concept of electromagnetism, which would eventually lead to transmitting images, had been unveiled in 1831, with a breakthrough in 1862 when Abbe Giovanna Caselli actually sent an image through wires. By 1876, a Boston civil servant, George Carey, was drawing sketches for what he called a ‘selenium camera’ and Eugene Goldstein was talking about ‘cathode rays’. Not content with inventing the telephone, Alexander Graham Bell, along with Thomas Edison, spent time in the 1880s examining the idea of using light to transmit sound, by which he envisaged images could be sent via his new device.

The massive World’s Fair in Paris in 1900 is remembered for many reasons. It brought the world’s attention to the spectacular Eiffel Tower, and it was held in conjunction with the newly revived Olympic Games, although the whole Olympic–World’s Fair tie-in was so shambolic that many competitors had no idea they’d actually won an Olympic medal. Australians were mostly interested in the victory of one of our swimmers, Frederick Lane, in the Olympic swimming obstacle race held in the Seine, with our boy proving fastest at climbing over water-based hurdles and diving under a boat over the 200-metre course. He’d already won the 200-metre freestyle that morning, swimming downstream. With such heady stuff going on, it was easy to overlook the bunch of turn-of-the-century geeks gathered elsewhere in Paris for the First International Congress of Electricity. It was even easier to miss the moment when a Russian scientist in attendance, Constantin Perskyi, used a new word for the idea of transmitting images. He called it ‘television’.

In the first decade of the 20th century, scientists split into two camps – those working on mechanical television, using rotating discs, and those exploring electronic television, chasing the cathode ray dream. In 1924 and 1925, America’s Charles Jenkins and Scotland’s John Logie Baird both showed rudimentary versions of mechanical TV, with Baird breaking new ground by transmitting moving silhouettes. By 1926, he was managing to transmit 30 lines of resolution at five frames per second.

On 9 April 1927, television became a reality with the first long-distance display, by Bell Telephone and the US Department of Commerce, of an image transmitted between Washington DC and New York. Secretary of Commerce, Herbert Hoover, was not about to underplay the achievement. ‘Today we have, in a sense, the transmission of sight for the first time in the world’s history,’ he said. ‘Human genius has now destroyed the impediment of distance in a new respect, and in a manner hitherto unknown.’

Some of the pioneers were now thinking about how to use all this technology. In 1928, Charles Jenkins applied for, and received, the world’s first-ever TV licence, ‘W3XK’. Within two years Jenkins had made more history by beaming the world’s first television commercial. The rest, as they say, is history.

For Australians, all they got to hear of this was little more than a few in-brief paragraphs in the occasional newspaper. Television was underway in the United Kingdom in the late 1930s but the British Broadcasting Commission had made a slow start, so not many Australians making the long trip across the world to the Old Country would have actually come into contact with the new medium. It was more likely that Australians might have seen the miracle of moving pictures in a small box in the United States, where the take-up was faster after network television began in July 1941. It would take until 1963 for the combined rest of the world to have more television sets than America.

Nevertheless, in Australia, TV was coming. By the start of 1953, when regular television broadcasts were unveiled in Japan, Australians would have heard of television being available everywhere from the USSR (1946), Canada (1947) and France (1949) to Mexico (1950), Brazil, Argentina, Holland (all 1951), Germany, Italy, the Dominican Republic and Venezuela (1952). In the life of the Australian Royal Commission, television had also been introduced in the Philippines, Switzerland and Belgium. Poland and Finland were getting ready to flick the switch. Being a late bloomer, Australia was able to learn from the mistakes of other countries, with the Royal Commission presumably noting the 1954 UNESCO Report that found television was struggling badly in Holland, Denmark, Germany and Italy because years of ‘experimental’ broadcasts had dampened the desire of consumers to bother to buy a set. The verdict was that Australia would do better to follow Canada’s example, test the technology in secret and then land, fully formed and ready to dazzle its public.

So, it wasn’t really a matter of if we’d get TV. The politicians were just nervous about what television might do if allowed to mutate without official legislation to control the monster.

‘TV safeguard for children advised,’ screeched the headline of The Sun-Herald on Sunday 9 May 1954, announcing the Commission’s findings. Nobody was turning to the newspaper’s much-vaunted ‘8 pages of comics’ before they’d read this story.

‘The Television Royal Commission’s report, issued in Canberra yesterday, advises the appointment of special committees to watch the interests of children’s and religious television programmes,’ the article began. ‘It says censorship of Australian “live” programmes would be impracticable, but that there should be some power to ban material likely to cause offence.’

Straight away, the commissioners were announcing their concern over content, and also that advertising would need to be controlled so that it did not become excessive. Has a group of public servants ever been so astute, so quickly?

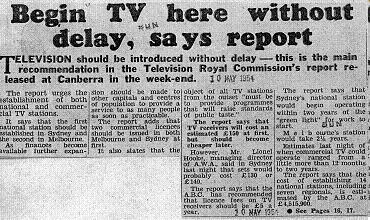

Monday’s papers couldn’t care less about such detail as protecting the eyes and minds of children. The Melbourne Sun News-Pictorial cut straight to the chase with the headline: ‘Begin TV here without delay, says report’.

The Royal Commission had recommended that national and commercial stations be established in Sydney and then Melbourne, with a warning that the ABC shouldn’t aim for success at the expense of its existing radio obligations. The report advocated further expansion into the other capital cities as more funds became available. Overall, the Royal Commission had estimated the cost of setting up an ABC television station in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth, Hobart, Newcastle and seven regional centres at about £4,515,900, including operating costs until 1959.

The commercial stations were expected to cost at least £250,000 and possibly as much as £500,000 each to establish. From the start, the Royal Commission believed there should be competition, with two licences in the two major capitals, and it was clear that any TV stations must have the overriding aim ‘to provide programmes that will raise standards of public taste’. Clearly, nobody at this stage had foreseen Big Brother or Chains of Love.

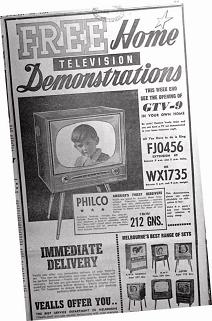

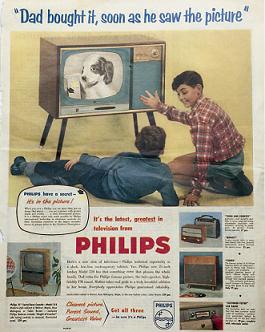

The report also suggested that a television receiver, to become known as a TV set, was likely to cost £150, but may become cheaper over time. However, the papers went straight to the manufacturers, who declared that they hoped to be selling units for £20 less than that. Companies like Astor, Kriesler, STC and Philips began preparing.

Estimates of when television could be up and running ranged from little more than 12 months away, to two years. Sydney had a head start because of the licence rollout, but Melbourne had the Olympic Games, starting in mid-November 1956, as an obvious target.

Keith Cairns, a former chief of staff for Melbourne’s Sun News-Pictorial, and more recently a newspaper executive, was in London for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in June 1953 when Menzies had first announced plans to explore television in Australia. Cairns was immediately commissioned with the task of exploring television in London, as the Herald & Weekly Times began preparing its licence bid.

But Cairns was quickly frustrated. ‘Britain had the BBC,’ Cairns said, in an interview not long before he died. ‘Commercial TV didn’t start there until a few years later, so there wasn’t much I could pick up in London. There was only the BBC and we wanted a commercial operation, which is what we very much were. Anyway, the BBC wasn’t noticeably co-operative. They weren’t too keen on helping some bloke from the sticks.’

By the time the bidders lined up, there were a handful in each city. In Sydney, one licence went to Amalgamated Television Services Pty Ltd, formed by Fairfax, radio stations 2UE and 2GB, Macquarie Broadcasting Services, the Sydney Sun and a few other partners. It would become ATN-7.

The other licence went to Television Corporation Limited (TCN-9), which was a joint venture between Consolidated Press, London’s Daily Mail newspaper, Philips, Paramount Film, radio stations 2SM and 2KY and others, including a promised number of shares left open for the public to buy. All anybody really needed to know was that TCN-9 was controlled by Frank Packer. That was certainly all that young Bruce Gyngell needed to hear. He was no longer working on his suntan.

‘The moment the announcement was made that Television Corporation got the licence, I naively wrote to four US TV networks, plus Columbia, Harvard, Yale and Stanford universities, saying we’d been granted the first commercial TV licence in Australia and asking what training they could offer us,’ he told ScreenSound. ‘I was a very bold 24-year-old typing with two fingers. I only received one reply from Sylvester L. Weaver Jnr, the president of NBC. Later I realised it was owned by RCA who thought they could sell equipment to us, but Philips was already part of Television Corporation, so that was covered.

‘I wrote to Frank Packer reminding him of the first conversation at Clyde’s party saying, “On February the 14th, you mentioned you were applying for a licence, I know you must be busy … etc, etc,” explaining that I had made arrangements and could go to NBC, could study at Columbia University, I had organised a student visa and had a round-the-world ticket, which I had already organised, so could I go? His secretary called and said yes, and can you take Alec Baz and Mike Ramsden in New York [AAP correspondent to the White House at the time] with you.’

Cairns had also looked to America. He had found a media company which was remarkably similar in size and existing media properties to the Herald & Weekly Times, which went into the Australian TV battle already boasting Melbourne’s top-rating radio station, 3DB, and its newspaper power, including the afternoon broadsheet, The Herald, with its sales of 440,000, and the morning tabloid, The Sun, which had a circulation of about 400,000.

‘This American operation had five TV stations and newspapers and radio and so on … they had a TV station [WEWS TV] in Cleveland, Ohio, which was very much like Melbourne,’ Cairns recalled. ‘It was comparable. I stayed there for some weeks and I was full of enthusiasm. This was something we had to be very much involved in.’

The HWT won its licence from a field that included Opposition Leader, Dr Evatt, and the federal secretary of the Australian Workers’ Union, Mr TNP Dougherty. But the Broadcasting Control Board didn’t have much of a decision to make.

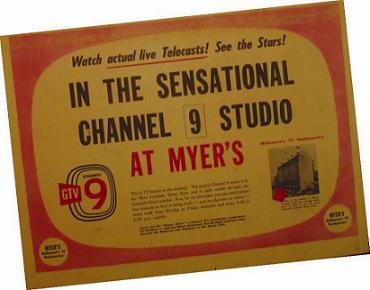

One licence went to General Television Corporation Pty Ltd, a shiny new entity specifically created for the task by Astor Television’s Sir Arthur Warner and backed by the newspapers The Argus and Australasian, as well as Hoyts Theatres, Greater Union Theatres, Electronic Industries Limited, JC Williamson Theatres Ltd and radio stations 3XY, 3UZ and 3KZ. Everybody wanted a piece of the new media.

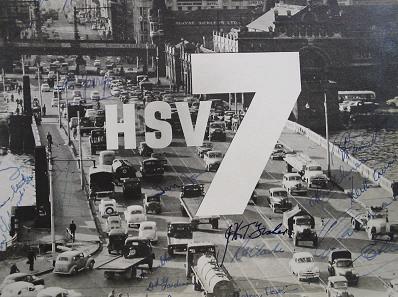

The HWT licence was won in an unusual alignment with Packer in a handshake agreement in Melbourne to work together against GTV and the Fairfax-dominated ATN in Sydney. (It was a partnership that lasted until the day in 1958 when Herald executives picked up the paper to read that Packer had bought GTV-9, despite promising them that he would alert them before making such a move. The Board of HSV was forced to do some fancy corporate footwork, eventually tying in with ATN-7 for a new partnership.)

The winners were announced in a 37-page report published on 18 April 1955, and the race was on. Gyngell decided early that it was essential that TCN-9 should be the first to broadcast in Australia; that being able to say you were first to air meant something important, even if he wasn’t sure what. In Melbourne, executives from GTV and Herald Sun Vision were telling newspaper reporters that they hoped to be on air in time for the Melbourne Olympics, only 18 months away. It was a ridiculous deadline, a crazy timeline to set themselves given how green they still were about how television even worked. But this was a time for confidence, and maybe a time for cowboys. Even the Control Board was making it up as they went along, admitting that their demand that overseas shareholders in the commercial licences be limited to 15 per cent was made despite suggestions at the public hearings that the Board had no right to make such claims.

As for choosing which station would carry which number, well, the Control Board decided that time-honoured methods would suffice. ‘We had all the elements of a chook raffle,’ Keith Cairns said. ‘The Control Board put the numbers in a hat and I picked Seven. He picked Nine. We were pleased because we wanted to be Seven.’ A life-long golfer, Cairns added: ‘We thought it was a lucky number, and in golfing parlance, a seven iron goes further than a nine iron.’ (Even today, Seven staff contest the annual Keith Cairns Golf Cup.)

Now the licences had been awarded and the clock was ticking, things began to move quickly. But nobody could be sure they were even on track. ‘Packer’s position on TV was “I don’t know if it’s going to take off, but everyone says I should be in it”, which is why he gave the head programming role to a 24-year-old,’ said Gyngell. ‘A lot of executives with financial backgrounds were brought in to run Nine, but it didn’t work out. They had no idea about TV and spent £3000 on curtains.’

Right throughout the process, there were instant winners and then there were those who would look back at opportunities lost. There was the potential bidder for a Sydney TV licence in 1954 – Bruce Gyngell remembered him hazily as Mr Scrimenger – who was somehow alleged to have connections to the Australian Communist Party or maybe China at a time when Prime Minister Menzies was deep in a ‘reds under the beds’ campaign. Exit stage left, Mr Scrimenger, forever branded as a potential polluter of Australian minds everywhere. Or the less sinister but equally forgotten bidder, Mack’s Happy Home Furniture, who threw a happy hat into the ring for a Melbourne licence, apparently acting under instructions from God, but came up short once the Herald & Weekly Times flexed their considerable muscle.

Others didn’t even spot the gold they were sitting on. The owner of a run-down weekender for sale on top of Mount Dandenong in 1955 was probably thrilled when his real estate agent broke the news that somebody was interested in buying his shack and its rocky land with a good view. The poor vendor wouldn’t have had any idea, until it was way too late, that the ‘Mr Smith’, or whatever faceless buyer’s name his agent was negotiating with, was actually Keith Cairns, by then general manager of HSV-7 and backed by all the financial might of the Herald & Weekly Times organisation. If he’d been able to see the HWT executives face-to-face, he might have had a vital inkling of how high the stakes were in that transaction. As far as the buyers were concerned, it went way beyond whether his weekender had woodworm or needed re-stumping.

If only … if only the weekender owner had realised that his little shack just happened to be sitting in the exact and only spot on the entire mountain where Seven could place its transmission tower to guarantee line-of-sight telecasts across Melbourne. If only he’d realised how vital that piece of land was, to host the giant tower that still stands there today, beaming Seven’s picture across the metropolis, the weekender’s owner might have been a little braver in how he played his cards. He definitely could have achieved a much, much better price.

Many of the lucky winners of that time were working in radio, especially at the Herald & Weekly Times’ top-rating radio station, 3DB, or the popular 3XY, with nothing but blind luck in timing to thank for the lucrative and exciting careers about to unfold before them.

‘I was able to raid 3DB,’ Keith Cairns said. ‘We had stand-up fights over that. Our salaries looked as though they would be better and the industry was going to be good. Initially, the struggle was to get [technical] staff. On my visit to WEWS Cleveland Ohio, I met superb people. They encouraged us to send our people and Packer’s people over there. We all went over and we recruited staff from all over the place when we got back. Some of our best blokes had been taxi drivers and all sorts of people. The nearest thing was still radio.’

A revue at the Princess Theatre was plundered for talent while those applying for jobs off the street were given wild choices, such as would they like to be an on-air presenter … or PA to new program manager, Colin Fraser, an ex-Herald Chief of Staff? Then again, why choose? Some took on more than one role, like teenager Don Bennetts, who joined as a cameraman and continued as a studio crew member while soon gaining fame as a performer on Hit Parade and Youth Take A Bow. (Bennetts’s fame was assured when he ran his car off an embankment near the Seven transmitter on Mount Dandenong and, on finally scrambling out of the wreck and back up the slope to the road, thrilled to be alive, was greeted by a woman exclaiming, ‘Why, it’s Don Bennetts!’ That made the paper.)

The stations had one obvious source of technical staff. Melbourne Tech (later the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology) had shown some foresight by developing television engineering and technician courses over the last few years and graduates poured straight into jobs – as did the lecturers, with Pulse Techniques lecturer Rod Biddle becoming Nine’s chief engineer, among others. In December 1955 engineers from the course were signed by HSV-7 and sent to 3DB because the television station hadn’t even been built yet; an army of workers was trying to convert the site of the old Herald Gravure printing plant in Dorcas Street, South Melbourne. In Bendigo Street, Richmond, an old Heinz factory site was being transformed into GTV-9. In Sydney, the remote Epping site was being readied by ATN-7 and a former dairy in Willoughby was now becoming the home of TCN-9. HSV was relying on employees from equipment provider Marconi to oversee the building of the Mount Dandenong transmitter and all video equipment, while AWA staff supervised the hooking up of audio gear.

It was around Easter 1956 when equipment began to arrive from overseas, including HSV-7’s outside broadcast (OB) van, which amazed everybody with its size. There is beautiful colour footage shot by a pioneer Seven cameraman Robin Clarke that shows the OB van being winched onto the docks and then cruising through the centre of town in 1950s Melbourne, driven triumphantly under a sunny sky. It was a shining day right up until the van reached the station’s South Melbourne headquarters, and was found to be too big for the garage doorway that had been built for it. Sledgehammers went to work on the bricks. Meanwhile, the studio equipment was delivered in such magnificent wooden packaging that there was competition among staff and management to keep the timber to build high quality shelving.

In July, HSV began to transmit a test pattern and music, so that television set installers had an image to aim for as they began installing sets into actual lounge rooms. These early sets were not like today’s TVs, which can be taken out of the cardboard box and plugged straight into the wall, ready for action, or feature one-touch automatic tuning of all available stations. They had to be individually tuned, and every time a set changed station, more tuning was required. An unexpected win for HSV was that more people started wanting sets because those who had them were enjoying being able to hear popular music beamed into their lounge rooms without DJs and all the other usual interruptions of commercial radio. Even without vision, television was a hit, thanks to popular acts like Crazy Otto and his Piano.

In Melbourne, everybody was focused on one thing – being on air in time for the Olympic Games. Asked if there was a sense of a space race, with a battle between Sydney and Melbourne stations to be first to officially broadcast, one engineer from the time said: ‘No, we never had a sense of that. Sydney might as well have been on the other side of the moon when it came to television. Because there was no cabling, no networking, between the cities, they were not remotely in our thoughts.’

Instead of rivalry, there was sheer excitement. HSV-7 had a grand total of 49 employees when the station went to air. In the months before, the management staff, including secretaries like Judy Macleod, would be invited into the office of Keith Cairns or program manager Colin Fraser when the men returned from buying trips to America.

‘Colin or Keith would say, “Oh, you should see what we’ve got!” and we’d go into their office and they’d put on a film to show us programs like Gunsmoke or I Love Lucy,’ she recalled. ‘It was the first time any of us had ever seen them and we simply couldn’t believe it. We all adored The Mickey Mouse Club. It was the greatest thing we’d ever seen. We walked around the office singing the theme song for days.’

The secretaries also built running jokes as they tried to survive this bizarre new world, bobbing between celebrity auditions and reports to their bosses from the technical staff. ‘We’re going to be a good station because we’ve got a 16-stack vestidual side-band filter on Mount Dandenong,’ they would say to visitors, poker-faced. One day, a man phoned to say he lived on Mount Dandenong, within sight of the new tower, and could he save the expense of buying an aerial for his house by simply pointing a mirror out the window at the giant transmitter? The engineers rolled around on the floor laughing, but how was he to know?

Before long, despite the crazy hours and the magnitude of the collective task, romances bloomed. A state away, Bruce Gyngell would have expected no less, saying years later: ‘I always said if no f***ing went on at a station then it wasn’t going to work. In the first four years I worked every single day. It was so much fun, why would you not want to be there? There was great hands-on enthusiasm, vitality and passion.’

Or as Roger Climpson said to Nine’s Sunday program recently, in a retrospective on the early days: ‘There were some pretty wild days there, yes, and there were some pretty wild parties, I’ll grant you that. Television was almost one huge party. Anybody who was in it was delighted to be in it because it was fun, because you were somebody important if you were in any way associated with television. People’s eyes would hang – “You’re in television? Wow!”’

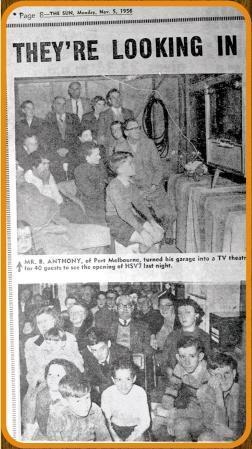

As the Olympics loomed, Astor was selling TV sets so quickly that people would pick them up from the factory’s back door, without bothering with a box or other packaging. These TVs cost three times the average monthly wage. Shops offered deals where people could trade in a piano for a TV receiver. The hype was building and by the time television actually went to air, there were an estimated 5000 sets in Australia tuning in. In Melbourne, 26 per cent of homes had a set, compared to only 12 per cent of Sydney homes, probably because the Games were in Melbourne. This was not including all the shopfront window sets that saw crowds gather to stare at this new phenomenon.

In Sydney, Bruce Gyngell was back in town after his big American adventure, which had included being lectured in television production at Columbia University by Mike Dann and Pat Weaver, later to father an actress daughter called Sigourney. Gyngell and his fellow Packer workmates also worked at WEWS TV, the non-union station in Ohio, which meant they could be, and were, thrown into everything, from cameraman to floor manager to editing. Gyngell was supposed to head to London for more research but at the last minute received a typical Packer telegram: ‘The Poms don’t know how to do it, cancel the trip.’ Packer had discovered that the first British attempts at commercial TV had reportedly made losses in the vicinity of £4 million.

Gyngell came back to Australia but was still thirsty for knowledge. ‘We [TCN] weren’t on air until September so I went to see Packer about going to KGMB in Honolulu for more experience, and he said, “This is not a travel department,” so I offered to pay for myself to go. Packer said “We’ll pay you and give you money for an allowance.” I went there for eight months, got more experience there, also at a non-union station, and learnt about splicing, presentation, worked on a cooking show, commercials … I learnt more in that period than previously. I experienced practical problems like if the copy was late or a guest hasn’t turned up. A month before TV went to air, I returned.’

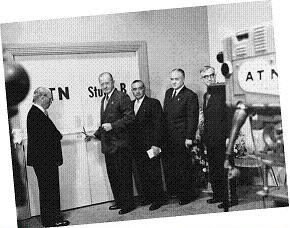

After Nine’s debut on 16 September 1956, with Gyngell jammed into the storeroom, ATN-7 set 2 December as its launch date. On that afternoon, a massive thunderstorm swept through Sydney. The roof of Seven’s only operational studio, Studio B, couldn’t cope and rain leaked onto the lighting console, which promptly died. As VIP guests prepared to wade through thick mud in the car park, to witness the opening night of this historic TV event, the actors and musicians were rehearsing by the light of car headlights shone into the studio as technicians frantically tried to revive the flooded console.

Yet ATN made it to air, its mishaps becoming just another of the many seat-of-the-pants stories from that crazy first year of television.

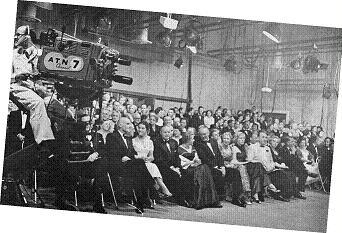

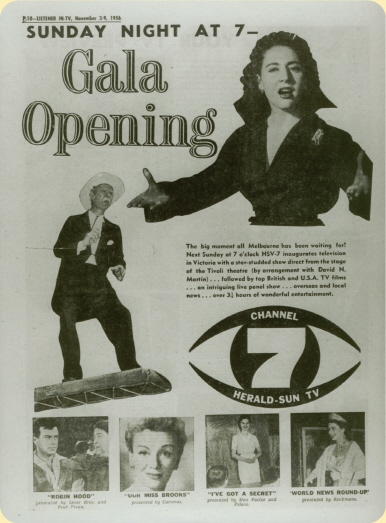

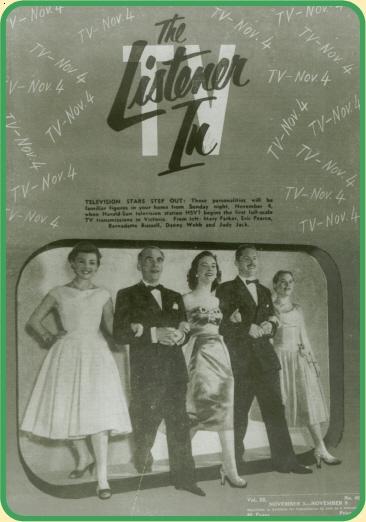

The opening night of HSV-7 – at what other time than 7 pm on Sunday 4 November – featured a welcome from Studio 2, soon to become the home of the news, The Hit Parade and other smaller shows, because yet again the larger Studio 1 wasn’t ready. Eric Pearce greeted viewers across Melbourne by smoking a pipe, and then a ballerina appeared to dance on his desk. It was heady stuff.

Luckily, the opening broadcast then crossed to an outside broadcast ‘with a star-studded show’ direct from the Tivoli Theatre, in Bourke Street. Young comedians like Gordon Chater and Barry Humphries were listed in the program but only in the wake of larger acts, such as Richard Hearne – AKA ‘Mr Pastry’, the star of Tivoli’s Olympic Follies – who performed his simply hilarious act, ‘The Lancers’.

Seven’s engineers had already worked out why the new medium was better than radio, hardly able to believe that they were laying cables and checking equipment while half-naked showgirls ran to and from the stage for a fortnight leading up to the big night. That might be why everybody backstage was too distracted to notice the effect of the heat of the studio lights on a fishbowl, which was an arty centrepiece of the opening. Life-saving cold water was added moments before HSV went to air, narrowly avoiding the network launching with a shot of a bowl of dead fish.

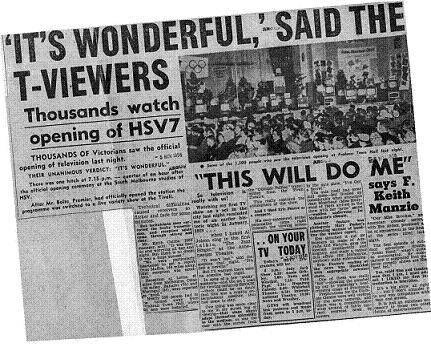

But the audience loved it. ‘This will do me,’ ran the headline in The Argus after HSV’s opening night, while the Age reported that the unanimous verdict of viewers of that first night was ‘It’s wonderful!’ – despite the picture disappearing for several minutes when Seven threw from the studio to the Tivoli. In the streets of the city and suburbs, large crowds of those who hadn’t been able to afford a TV receiver in time for the opening gathered in front of store windows, huddled to watch the magic. Nearly 300 people had to be turned away from the packed Prahran Town Hall where more than a dozen TV sets had been lined up on the stage, 1500 people craning their necks for a better view.

In the days to follow, getting a picture to air on Seven was nothing but an adventure. A children’s show producer got over-excited one day and brought an elephant, with disastrous results, while that show’s host managed to set fire to the studio no less than three times, setting off the sprinkler system, live on air. Three times! Meanwhile, Seven’s studio crew miscalculated how much dry ice would be needed for a big stage number, resulting in Melbourne TV’s first screening of a musical fog.

At least they were in better shape than Sydney’s Australian Broadcasting Commission station, ABN-2, which lurched to air on Monday 5 November, the day after HSV got going, but with technical hitches all over the place. During the first speech, by ABC chairman Sir Richard Boyer, the picture kept switching randomly to those sitting to the side, waiting their turn to speak. Because the studio lights were so bright, the Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, and Senator McKenna had their eyes closed, giving the appearance that the Australian Prime Minister had fallen asleep in his first-ever appearance on television. When Sir Richard had finished and sat down, the camera promptly flicked off Sir Robert at the podium to the ABC head, eyes clamped shut against the glare and seemingly dozing through Menzies’s historic welcoming speech.

Things didn’t get better later when a technician walked in and out of shot, and then, during ABN’s first attempt at a news bulletin, another unexpected camera switch filmed a crew member’s back and then the host of the opening ceremony, Michael Charlton, who was surprised to find himself on air while smoking a cigarette after his performance. ‘You’ve caught us on the hop a bit,’ he said, before grabbing some headphones so he could talk to the news director. Finally, the news resumed.

Despite all this, the Prime Minister was gracious about the mishaps, declaring the station to be ‘a triumph for technicians’. Mr Menzies even felt moved to point out to the 150 guests in the studio, and the wider viewing audience, that the average person had no idea how much work was required to put an Australian TV station on the air.

The hard work was being rewarded by viewer numbers at HSV. More than 200,000 people were reported to have seen the opening night, and over the following week reports came in from country centres confirming that the station could be seen in towns like Hamilton, Colac, Morwell, Lorne and Alexandra. Seven celebrated by unveiling Australia’s first broadcast talent quest, Stairway to the Stars, and possibly our first weather girl, with Mrs Brenda Sender, ‘wife of a city businessman’, being chosen from several applicants to tell viewers the weather news at 7.10 pm and 9.40 pm every Friday evening, starting in mid-November. Seven also launched the ambitious Wedding Day, where, in the opening show, radio personality John Stuart, with actor Carl Bleazby acting as master of ceremonies, interviewed newly-weds George and Diane Footit, who then took part in a quasi-reception and contested for prizes, such as a portable radio or a knitting machine. The show ended with the couple, having changed into ‘going away’ clothes, being waved goodbye as they departed on their honeymoon.

Clearly, there was already a need for the steadying influence of the ABC in Melbourne. Within a couple of weeks, ABV-2 was transmitting a test pattern in time for the Games. The official opening of the government station was set for Monday 19 November, with a half-hour opening ceremony featuring the usual dignitaries and politicians, to be followed by a selection from the intended regular programming. The Frankie Lane Show featured Frankie singing alone and with guests, and was followed by the Mitchell Boys Choir, which had appeared in a couple of Bing Crosby films, including White Christmas, and then Fabian of Scotland Yard. An extended feature, This is the ABC, introducing viewers to the humorous as well as the serious moments in a day in the life of the national broadcaster, was to be followed by a live variety show, Seeing Stars, hosted by Peggy Brooks, just back from overseas, and finally a documentary on World War II, just to finish on the up. The Victorian manager of ABV-2, Ewan Chapple, explained to Listener In-TV that the station was not attempting to dazzle with spectacle on the opening night, instead looking to emphasise the various activities of the ABC and its need to cater for all sections of the community. So presumably no burning studios there.

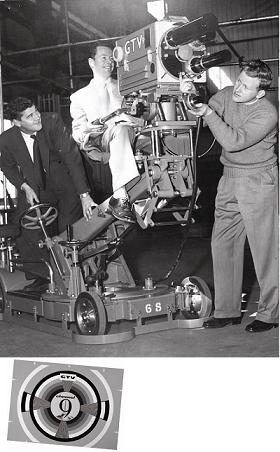

All this was before Melbourne’s TV pioneers had attempted to cover an Olympic Games. Only a few days into the world’s biggest sporting event, which even the International Olympic Committee didn’t really want them to cover because they thought TV equipment would get in the way of spectators, HSV’s rookie technicians knew they were up against it. The station had three cameras for outside broadcasts – massive, awkward boxes weighing roughly 80 kilograms each. There were up to 300 metres of cables per camera, each up to 70 metres long, and thick with brass connections at both ends; lots more weight to be lugged by the HSV team of six. There were also the microwave links, which were like satellite dishes two metres in diameter and felt like they weighed a tonne. All of this equipment, every last piece of it, had to be set up from scratch in time for the morning start of the athletic events at the MCG. The moment the athletics finished, it had to be packed up entirely, and driven to the State Swimming Centre on Swan Street, behind a police escort. It then had to be re-set for the swimming, which would finish around 10.30 pm. The technicians had to pack up and take everything back to the station, finishing at about 1.30 am, and be back by 5 am, ready for a new day.

Every third day, each member of the team would be given a ‘rest’ day, working only 15 hours in the Dorcas St studio crew, so that no heavy lifting was required, but the strain was telling. One technician who lived in Mount Martha, an impossible drive away under the circumstances, took to sleeping on a couch from one of the studio sets, with a piano cover to keep him warm. The first crew member in each morning would wander into the studio, kick him awake and, after staggering off for a shower, he was ready to head to the MCG to start all over again.

There wasn’t much room for error, which is why, a few days in, as they packed up at the MCG, they were mortified to watch one of the microwave bearers sail off the top of the MCG grandstand, landing heavily on an ABC truck. ‘That made us check whether we had public risk insurance,’ Keith Cairns chuckled in memory, but for the engineers, losing the station’s no-claim-bonus was the last thing on their minds.

‘We were standing there, looking at the damage and bemoaning how we were going to possibly get it to work again, when an ABC guy in a dustcoat appeared at the top of the stairs and said: “Excuse me, but I’m from the ABC and your link just hit our truck and I have to make a report,”’ Ron Place remembered. The bearer’s actual dish was buckled, the wave-guideline, which was crucial, was bent, and the heavy diecast box was completely battered. Where the cable actually connected was completely severed. Assistant chief engineer Lyle Lloyd headed off to The Herald’s machine shop with the whole mess and reappeared the next morning with the bearer fixed and ready for action. Nobody could believe it. ‘To work, the wave-guide part of it had to be repaired to something like 2- to 3-thousandths of an inch and they’d done it,’ Place said. ‘The funniest thing was that the link itself had always struggled to meet the Control Board’s specifications; it had always been our dodgiest link. After that miraculous overnight repair job, it was one of our best.’

GTV-9 and ABV-2 were working just as hard to cover the Games, although viewer figures came through that suggested 97 per cent of Melbourne TV sets were watching the Olympics on Seven. Keith Cairns was so chuffed that he arrived at the MCG during the evening bump-out during the second week of the Games and suggested adding extra venues to the telecast. Utterly exhausted, the technicians were not polite in their response, prompting an attempted inspirational talk from Cairns about the importance of what they were all doing, the greatness of their achievements and so on.

But they weren’t the only ones doing it tough. On the Wednesday night, on the eve of the opening ceremony, a lonely figure had sat in the new Olympic Stand of the MCG, quietly sobbing, and the Games hadn’t even begun.

In years to come, Alf Potter would become Seven’s directing guru of all outside broadcasts, through the Olympics as well as covering the football, golf and anything else. But on this day, he was a scared former 3DB radio producer who realised he was so far out of his depth that there was no land in sight.

‘I went there by myself; I didn’t have anybody with me and the other two stations had about a dozen people there,’ he said in an interview before he died. ‘The ABC, they had two BBC producers and an American producer with all the assistants because they knew how to do it. We didn’t. At Nine they were a bit the same. They had two Americans and they had assistants and all that sort of thing, and there is me in the stand, all on me bloody own. I thought, “Jesus, what have I let myself in for? What am I doing here?” Because I really didn’t know and didn’t realise what I had got myself into. I actually broke down. I howled. I was approaching middle age, and I was pretty tough because I had been in radio for a hell of a long time, but I sat in the MCG stand, in the new stand, and shed tears because … just because of the pressure. It was enormous pressure. Nobody had taught me, because I hadn’t been overseas. I had to say to one of the fellers that had been overseas – the assistant chief engineer at that stage – “How do you get from one camera to another?” and he said, “Well, in America they call ‘standby camera 1, ready 1, take 1’, and that’s the way you do it.” And that’s the way I learnt.’

Once the cameras started rolling, Potter became a legend for simply creating his own rules and, in the process, accidentally-on-purpose creating an entirely original Australian way of covering sport.

‘Three cameras is all we had,’ he recalled. ‘No mini things or anything like that, no hand-held cameras, of course, and very archaic zoom lenses. We had a 40-inch and a 25-inch fixed lens that I used to put on the same turret, which wasn’t done. When Peter Coates came out and we were doing drama together, I was tracking in the studio with a 17-inch lens and he said, “What are you doing?” and I said, “Tracking in.” He said, “You can’t do that. That’s a 17-inch lens.” I said, “Yeah?” He said, “Well, you can’t do it; it’s not done,’’ and I said, “Have a look at the bloody picture. What’s the matter with it?” He said, “Nothing,” and I said, “Well, I’m doing it!” So, you know, it was innocence abroad.’

In Sydney, without the Olympic pressure, Gyngell and Nine were having a ball. ‘In the early days I was director of programming and read weekend news to save overtime for Chuck Faulkner,’ Gyngell said. ‘I also logged transmission on weekends in handwriting and copied it [on a Gestetner machine] – we had no staff – and presented the game show, Name That Tune, sponsored by the Women’s Weekly. We were only on air until 4 November for a couple of hours a night, closed down at 9.30 pm, and news was only 15 minutes initially.’

On 2 December, ATN-7 joined them on air and the battle to be ‘first’ was on in earnest. The day after its waterlogged launch, ATN unveiled what they claimed was Australia’s first tonight show, as Keith Walshe presented Sydney Tonight. Seven also claimed to have screened the first nightly current affairs show, with Howard Craven’s At Seven on 7, that day. Presumably, Captain Fortune was the first children’s program, and featured a man with a bad beard presiding over a bunch of puppets and nervous-looking kids. Over the first 12 months of television broadcasting, Seven would also claim the first breakfast show, as Ray Taylor presented Today, Del Cartwright’s Your Home as the first ‘women’s program’, and then there was the first quiz show, The Price is Right, the first soapie, Autumn Affair, and the first live musical on camera, Pardon Miss Wescott.

Of course, Gyngell and his crew weren’t sitting on their hands. The 24-year-old program director had had his moment in history and had followed it up by introducing his own work, Australia’s first documentary for television – about Australian television.

‘I did a 30-minute program called This Is Television which showed the former dairy where Nine [Sydney] is now, the tower being built and showed what a camera, control room looks like – a basic textbook on TV. I narrated and produced it with Mike Ramsden. Few people had seen TV at that stage,’ he said.

‘We planned that after my introduction, Chuck Faulkner would present the opening night. I opened with “Ladies and gentlemen, good evening and welcome to television.” At Columbia [University], I learned to be succinct, and after thinking about it, I finally came up with that phrase. Then at 6.30 pm, we planned for This Is Television to run, followed by Johnny O’Connor Presents, and then Campfire Favourites, which was coming live from St David’s Hall in Surry Hills, a church hall we set up to do live TV from.

‘On the Saturday night before the first transmission, we found we couldn’t go between the Nine studios and the church hall without a “rollover” all the time. We had a “sync pulse” generator problem so we needed someone to do the live bits between transmission, which is how I ended up hosting.’

Of the programming that would follow over the coming months, Gyngell was disarmingly honest. ‘Everything we did was new and exciting, and some was probably dreadful but there was an enormous enthusiasm; we were all young. Melbourne had a show called Your Hit Parade, which [featured] salesmen miming Elvis Presley, a bizarre program. We ran it at Nine on Thursday and it rated well. On Saturday afternoons I just played music over test patterns, but radio complained, so I created a show called TV Disc Jockey. We just played records to a visual of a record going around and around. Phillips offered us some records, Col Joye’s band came in to play live, then people came into the studio to dance – it built up. When John Godsen went on holidays in 1957, I asked Brian Henderson in to do TV Disc Jockey. Henderson was better than Godsen; the show soon became Bandstand which moved to 6.30 pm each night. All our sixties music stars came out of Bandstand.’

The original TV licences came with the handicap that stations could only spend a maximum of £25,000 per year on overseas content; this was a meagre amount that only succeeded in having already-hardened US television executives stare at the Australian negotiators. Gyngell bartered to receive his first three years’ worth of allowance in one hit so that he could bargain with longer term contracts for shows, while Cairns said eventually Packer and the HWT teamed to pool their resources and buy better shows, for HSV-7 and TCN-9.

‘Back then, the Herald & Weekly Times and ACP had a relationship with Roy Disney, through books and comics in their newspapers, which is why we could buy the Disneyland show,’ Gyngell said. ‘It ran at 7.30 on Mondays, followed by I Love Lucy, so the first six weeks on air was a miscellany of programming.

Nine Melbourne didn’t go to air for another six weeks, and they didn’t have enough programs, so we ran odd programs and English plays. In those days people would watch anything. By January we had Disneyland and I Love Lucy. Schaeffer pens sponsored I Love Lucy and wanted a live ad. Brian Henderson had a radio show called When A Girl Marries at the time, and I asked him to do a commercial for the pens and he got paid £4 for the night.’

At ATN-7, there were more scenes of bravado and seat-of-pants performance. Chris Beard was a young writer on the Captain Fortune show, and would go on to be on Revue 61. But his first day at ATN saw him thrown into dual roles.

‘I started as a booth announcer and host of Smalltime on the same day,’ he wrote in an ATN book celebrating the early years. ‘Newsreader Charles Cousens introduced me to the booth and told me he’d come back to help me from time to time. I never saw him again! I had to learn it all from scratch. I’d introduce Smalltime from the booth, then run upstairs to the studio.’

He would have bumped into plenty of talent in the corridors. Bob Dyer was preparing to move his quiz show Pick-a-Box from radio to television, debuting in 1957. Other early ATN stars included Howard Craven, Del Cartwright and Brian Wright. At Nine, Brian Henderson was now becoming established as the king of Bandstand, while others like Roger Climpson, Bobby Limb and his wife, Dawn, were on their way to TV fame.

In Melbourne, 70-year-old comedian Syd Hollister could be found at HSV-7, no doubt unfussed by this new world. Syd had been an early star on radio in the twenties, then performed on Australia’s first ‘talkie’ film, Spur of the Moment, in 1930, and had now found a gig on The Happy Gang, later to be called Sunnyside Up. Who knows, if Syd had hung around, he might have been an internet star.

Meanwhile, Don Bennetts was doing less and less camerawork and more and more celebrity interviews, while Eric Pearce read the news, Bert Newton, Brian Naylor and Danny Webb proved to be popular young hosts and the dashing John D’Arcy crooned to the camera. Hit Parade beauty Bernadette Russell raised eyebrows by taking the first genuine bubble bath in Victorian TV history, with Seven staff building a complete bathroom, with plumbing, in the studio for the occasion.

At GTV-9, general manager Colin Bednall and senior producer Norm Spencer saw a bug-eyed kid from radio 3UZ reading donations on a Red Cross telethon. The kid seemed to have a spark, a strange charisma that, along with his lightning mouth, made him stand out. On something approaching a whim, Bednall and Spencer asked Graham Kennedy if he’d like to host a planned variety show, In Melbourne Tonight. They offered serious money, too – £10 per show, five nights a week. He said yes.

For those lucky enough to have been among the pioneers – those who had created television out of thin air – the sense of achievement began to sink in. Somebody in Melbourne had the idea to organise an exclusive Television Ball at a swanky dance club in St Kilda. Glamorous on-air stars, behind-the-scenes staff and hangers-on from all three networks, GTV, HSV and ABV, turned out in their best ball gowns and black tie to share the triumph. On the dance floor, wannabe stars busted their biggest moves, desperately hoping to be discovered by the executives in the room, wanting badly to belong.

Towards the end of the night, the orchestra broke into the Mickey Mouse Club theme song and a ballroom full of people who knew they were at the cutting edge of the greatest adventure in media erupted. As one, they sang, ‘Em Eye See, Kay Ee Why …’ They sang as though there was no tomorrow, which couldn’t have been more wrong. In fact, they sang as you can only sing when you know, deep down, that you own tomorrow.

Australian television was on air.

THE PIONEERS

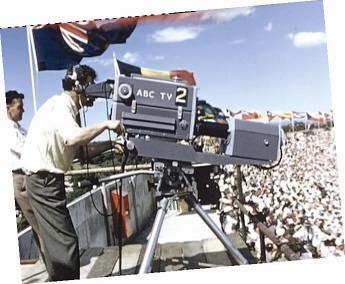

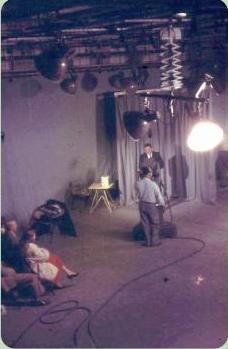

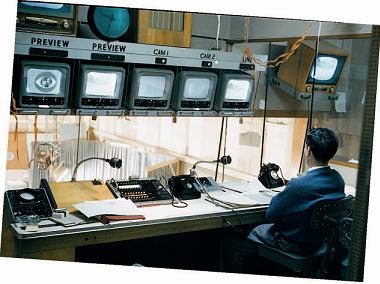

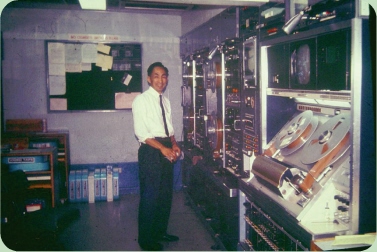

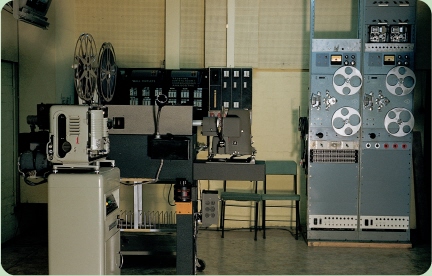

From a technical point of view, most of Australia’s early TV workers were working with the unknown – almost making it up as they went along. But they displayed great ingenuity, a remarkable capacity to learn and, in the end, achieved great things. These photographs, taken by a number of different behind-the-scenes crewmembers at HSV-7 in Melbourne in the mid-to-late 1950s, give a rare insight into life behind the cameras in those pioneering days.

Harold Aspinall at the Teletheatre audio desk.

The camera control room at Seven in the station’s early days.

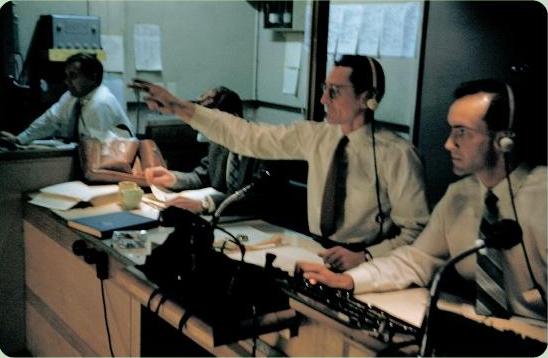

Inside Channel 7’s first outside broadcast van, being commissioned in 1956.

The men behind the camera were rarely seen, but their work was vital.

A peek inside a production studio at Channel 7, with Doug Elliott doing a live ad.

Peter Gorman in the original Control Room 2 at Channel 7, operating a direct switching vision mixer.

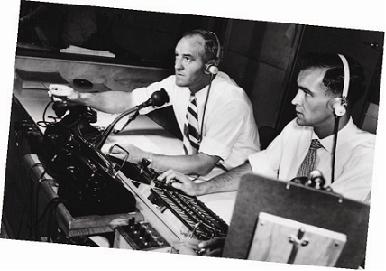

Jim Upshaw (Director of Hit Parade) and Dick Jones in Channel 7’s Control Room 1.

Roly Lau at one of the first two video tape recorders at HSV-7.

A look inside the telecine room, showing Stancil-Hoffman 16 mm sound recorders/players.