My Family and Myself

The picture books in this section represent the child’s comfort zone. Primary relationships with parents, grandparents, or siblings make up the stories. The books feature everyday concerns, such as going to sleep, wanting a pet, welcoming a new baby, or visiting Grandma and Grandpa’s house. The characters are human, or can be animals if anthropomorphized. Some of the stories are set in other countries or cultures but concern universal feelings and experiences.

A look at the experience of being a big brother, this story is told from the point of view of the dethroned “king.” He reveled in his role as the center of attention, but now his parents and grandparents dote on his baby brother. The baby even plays with his toys. But when the baby chews on his baseball glove and big brother has a meltdown, his mom gives him sympathy and reminds him of how much he can do that little brother cannot. With rich colors and facial expressions that reveal a range of emotions, the illustrations complement the text and its moods of resentment and anger, then pride and love. The font shows what is important: certain words are larger, especially I and mine. Any older child who has had to deal with sibling rivalry will relate to the king. For a big sister-little sister variant, see Rosie and Buttercup by Chieri Uegaki (Kids Can, 2008).

Anyone who has ever resisted going to sleep, or who has dealt with a child doing the same, will relate to this book. While her mother entices Alice with flowers and tea and a quilt, the little girl insists that each item be blue. Finally, when her mother turns off the lamp, the moonlight turns everything in her room that color, and she can finally sleep. The ink, watercolor, and gouache illustrations reflect Alice’s restlessness, but then, as the blueness of the moonlight comes in, create a mood of peace and rest. The text and illustrations capture perfectly the illogic of Alice’s demands and the magic of the color-changing properties of moonlight. Pair this with Jonathan Bean’s At Night (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2007), the story of a little girl with insomnia who finally finds rest on a rooftop, and Mij Kelly’s William and the Night Train (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2000), where a wide-awake boy finds sleep on the train to Tomorrow.

In first person, big brother Chong explains the Korean celebration of tol, for a baby’s first birthday, to his baby sister and to the readers. He looks forward especially to toljabee, a game where the birthday child selects from a number of objects; what she picks is an indication of her future. Ink-and-watercolor illustrations show Chong and Sara, their parents, grandparents, and other relatives and friends in a celebratory mood, enhanced by bright colors and some traditional costumes. Bold black lines surround the colors and provide a pleasing contrast. Throughout the story, the family speculates on little Sara’s future occupation by what she seems to enjoy. A glossary of Korean words and an author’s note at the end offer more information about this celebration.

A little brother, outshone by his stamp-collecting and coin-collecting older siblings, discovers something that interests him. Max now collects words by cutting them out of publications and eventually makes them into sentences and then stories. The marvelously quirky illustrations feature differing points of view, dependent upon scene: a bird’s-eye view of the older brothers’ collections, Max in a chair with the words displayed in front of and larger than him, and a small Max and his brothers entering into a story of a worm and a large crocodile. The words Max collects progress from simple typescript to colorful and shapely; the word pancakes features round and tan letters, hissed portrays two green snakes as the ss’s. Continue witnessing the power of words with Max’s Dragon (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2008), where Max and his brothers search for rhyming words.

This book provides a splendid example of the use of contrast in story and illustration. Entering this story from the title page, readers and listeners may believe that it is about a mean rabbit threatening a small animal’s house in a tree stump. But through the course of the narrative and enhanced by the illustrations in gouache and acrylic with pencil, the rabbit is not who he appears to be. The illustrations of the Big Bad Bunny appear wild and drawn in an almost childlike way (note the mean black eyebrows). His splashing and gnawing and stomping come alive through the action and color of the drawings. In contrast, the illustrations of the house where Mama Mouse takes care of her babies exude calm and orderliness. Although green is the dominant color, because much of the action happens outside, bright splashes of orange and red bring out the fierceness of the title character. At its heart, this is a story of a mother’s love for her child who has imagined an alter ego and then become frightened by it.

The old adage “The more things change, the more they stay the same” rings true as the theme of this book. A little boy does not want to make his bed because he feels he has already done too many chores. His mother tells him about his grandmother, who said the same thing in 1953, when she heard the story from her mother about her grandfather, who said the same thing in 1911, and back through history. The playful illustrations, in watercolor and digitally finished, depict the rooms, beds, and toys of the children; the year is also part of the illustration. The repetition of the title question is amusing, while the enumeration of particular chores is instructive. A good book for discussion (notice how the number of toys decreases as history rolls back), this would also work as a supplement to social studies. At the end of the book, a two-page “Chores through the Ages” provides information on children’s lives and playthings from prehistoric times through the present day.

In a twist on the familiar child-wants-a-pet plot, this story features a little girl bear who wants a child. As soon as Lucy sees the “critter” in her part of the forest, she knows that he is the perfect pet for her. True to form, Mother Bear says all the things that a human mother would say. The illustrations, a combination of pencil, construction paper, wood, and some digital, feature an appealing Lucy and her adorable little boy enjoying typical activities together. The text of the narrative is set off in rectangular boxes, while dialogue appears in word balloons of a different color, hand-lettered by Brown. Illustrations are bordered on each page with a thin frame of different-colored woods, corresponding to the forest setting. All good things must end, as Lucy discovers when her pet boy goes missing, but a twist on the last page provides a humorous ending and speculation for what comes next in her search for a pet. With the almost universal theme of wanting a pet, the cross-species behaviors, and humorous situations, this book will appeal to most readers and listeners. For a read-alike, see C’mere, Boy! by Sharon Jennings (Kids Can, 2010).

Thirteen different pairs of dads and sons fill the pages of this celebration of a father’s love and support. Each two-page spread contains a large illustration across the top, with four smaller illustrations in a band below, and then text in a narrow band at the bottom. The beautifully textured art features a diverse group of fathers who differ ethnically and in other ways. There is a father who looks like a grandfather. One of the fathers is blind, with a guide dog and cane. In each setting, the father and son enjoy activities that any child could relate to: walking in the park, playing hide-and-seek, making faces. For those children who call their father something other than Dad, the names Pop, mi papá, Pa, and Papa appear. The very last page turn reveals twenty-four small squares, each with the fathers and sons from throughout the book participating in even more fun activities. A beautiful look at the father-son bond, through all seasons, in many parts of the country, and with many loving fathers.

Esme is one lucky little girl. Her farmer grandfather tells her that they will find a pet for her at the auction. After searching, they finally find one they can both agree on: Trudy the goat. Esme loves her new pet. Soon family, friends, and neighbors realize that Trudy is special, too, for she can forecast when it will snow. But as winter deepens, Trudy gives up her weather-predicting ways in order to concentrate on something even more special. This gentle book portrays the love of grandparents and granddaughter, as well as the love of a little girl for her farm pet. Read-alouds will be fun as the dialogue lends itself to the interpretation of grandfather’s gruff, yet gentle sentiments and neighbors’ enthusiastic comments. The illustrations, rendered in acrylic paints, seamlessly combine pastoral quietness and the activity of chores with a bit of humor. The browns and tans of autumn give way to the whites and blues of winter as time passes and readers head for the payoff: Trudy and her baby, who seems to have a forecasting ability of her own.

The cover gives a mighty big clue to the story this book holds: a small pig has blown a huge pink bubble that encircles the words of the title. Then there are the front endpapers, full of big and small bubbles being blown by the same pig. In the story, the bubble-blowing pig, Ruben, receives some gum from his visiting grandmother. While his mother recites the gum rules to Ruben and his little brother, Julius (you can just tell they’ve heard these before!), Ruben gets busy chewing his in all sorts of positions and motions. All this is hilariously pictured in small black, gray, red, and pink drawings. Action words portraying the unwrapping, snapping, stretching, and smacking accompany, and become part of, the illustrations. Readers can anticipate the trouble of the title as Ruben systematically ignores his mother’s three rules and finally makes a giant bubble mess in the largest picture of the story. Be sure to notice the final endpapers, similar to the front ones, but full of popped bobbles. Ruben takes naughtiness to the most entertaining level.

Oh, to be the middle child, between an older brother and a baby sister who can seemingly do no wrong and who get all the privileges. With a text that imparts the rhythm and the pacing of a blues song, and the pencil-and-watercolor illustrations that wackily portray people and events, the story introduces the forgotten child. The humor carries through with garish colors that culminate at an amusement park, where middle child Lee sings his song and plays his guitar to hordes of other middles, including his parents. Check his pompadour and shirt collar, which go into full Elvis mode by the end of the story. A marvelous example of illustrations that add an extra layer to the text, in this case with goofiness and the put-upon demeanor of Lee. Contrast to Elizabeth Winthrop’s Squashed in the Middle (Holt, 2005), which has a more realistic and gentle tone.

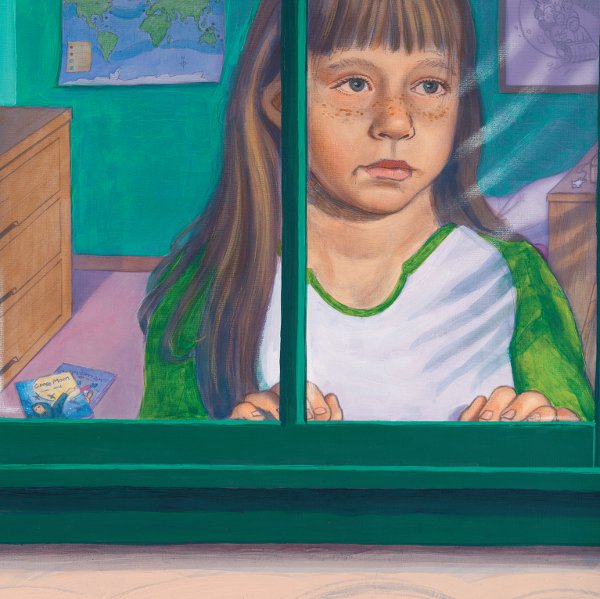

Magdalena waits for the annual arrival of the sea turtles with her grandmother. As the turtles lay their eggs in the sand, the girl protects them from predators and garbage on the beach. When her grandmother dies, a heartbroken Magdalena becomes angry. But sadness and hope mingle in the story, as eventually she goes out to the beach to witness the newly hatched turtles making their journey back to the sea. The realistic illustrations reflect the wonder of this part of the turtles’ journey, the wisdom being passed from one generation to the next, and Magdalena’s sadness at her grandmother’s passing. (See figure 2.1.) Rich blue-and-green illustrations match the sea, but also the characters’ clothing, providing continuity. Skillfully rendered, the illustrations of the turtles are awe inspiring.

Crum and Thompson take readers and listeners through a summer storm in the country. A farm family, consisting of parents and two children, feel a change in the weather, see the darkening sky, and run for shelter just before the rain and hail hit. Humorous illustrations, in watercolor, gouache, pastel, crayon, and collage, capture the excitement and fear of a potentially damaging storm. The side story of Maizey the hen and her strange behavior is resolved when everyone discovers she was protecting a kitten. The text, with strong verbs, is just right for a storm story. The author’s poetry background shows in her phrases that arouse the senses. Readers will almost be able to feel the humid air of a languid summer day, hear the frenzy of wind and rain and hail, and finally smell the after-rain. Sounds and bits of dialogue become part of the illustrations, which make it all seem very immediate. A good story to supplement a discussion about storms or farms. A complement to this, Like a Hundred Drums by Annette Griessman (Houghton Mifflin, 2006), also portrays a thunderstorm in a rural area.

A wonderful example of illustrations completing a story, this book takes on a common childhood experience—moving to a new house. Reading the text only, one would assume that two children leave the old house, ride to the new house, explore rooms, unpack, and spend a first night there. But the illustrations, pencil and digital, tell a different story: a little girl and her stuffed elephant experience these events. In some of the illustrations, especially where emotions run high, Stella the elephant is portrayed as huge. In others, she appears as a normal-sized toy. The ending introduces the neighbors, including a little boy with a stuffed giraffe. Obviously, these two will be friends, as the last page shows them playing cards with imaginary giant-sized animals. This story comforts as it tackles a standard childhood situation with gentle humor and a steadfast friend.

Many “diva” books have appeared recently, but Falconer’s Olivia titles belong near the top of the heap. With rather spare illustrations—notice the effective use of shading to add depth and texture—the books feature an anthropomorphized young pig who clearly sees herself as the center of attention of her family. The facial expressions and reactions of her parents and two younger brothers reinforce the humor that emanates from Olivia and her wild ideas. In this title, she becomes a one-woman band to accompany fireworks. Parents and teachers will recognize familiar situations and conversations; young readers and listeners will identify with the irrepressible and ever-creative Olivia. Everyone will respond to the humor, both broad and sly, as they enter into Olivia’s world. Colorful illustrations in charcoal and gouache consist of black, white, and gray, with splashes of red and blue; several pages, especially in the fireworks scenes, contain much more color on a dark background. Look for Olivia’s “Supreme dream” on the final page, which gives an idea of her ego.

A collection of fears could be scary, but this book makes them manageable. Little Mouse acknowledges her fears on each page spread, conveniently labeled with the particular phobia portrayed. A stunning array of these fears, some common (fear of spiders) and some not (fear of clocks), come to scary life through the illustrations of Little Mouse and her pencil. A color scheme of muted shades of tan, with black and white and occasional splashes of red and blue, lends an air of secrecy and fear. The illustrations, oil-based pencil and watercolor, also contain found objects. Several pages feature foldouts: of a newspaper, a map, and a postcard. Pages with chewed corners and illustrations of spills continue the theme of a little mouse creating the book as the reader pages through. Never fear! The twist ending makes it all worthwhile.

When his mami remarries, Xavier gains a stepfather plus a stepbrother, Chris. In a series of twenty short poems, Xavier tells the reader all about his resentment and his battles with Chris. But along the way, he finds out why Chris feels he has to be the perfect child and what happened to his mother. Each poem is a perfect jewel of a feeling, an event, or an emotion that Xavier works through. The gouache illustrations reflect these feelings, some realistically and some symbolically. For example, on one two-page spread, Xavier on a pizza in outer space looks on as his mother and the two interlopers play on another pizza on the facing page. In another, a tiny Xavier cowers on a page filled with the huge feet of his stepdad and stepbrother. A wonderful book for the study and appreciation of poetry, for the portrayal of a blended family that many students will relate to, for the depiction of an interracial family (Hispanic and African American), and for a story with a truly happy ending.

Violet, a little bunny who is gaga over the color pink, is disappointed when her mother is too sick to go to the Pink Girls Pink-nic. But that’s putting it mildly; with her exuberant body language and excitable language, Violet leaves no one guessing what she thinks. The character that gets to “pink up” is none other than her daddy. Bright cartoon illustrations—heavy on pink, of course—feature Violet and members of her family and friends with hilarity. The text features many exclamation points and differing font sizes and is integrated around the illustrations. This book is geared to those who cannot get enough of the color pink, but it also offers a spirited story about a dad who is a good sport. Contrast the tone with Nan Gregory’s Pink (Groundwood, 2007), which delves into class differences and envy.

Told in first person by a little girl who loves to chase chickens, this story delights in action, attitude, and surprise. Her prime target is Miss Hen, plump and beautiful—and a good runner. The lively collage illustrations present each chicken as an individual. Notice the fence as music staff and other collage elements in the clothes and food. Cutout letters, which make up the title in the cover art, pop up throughout the book to represent the squawks of the birds. Lest adults think that the chicken chaser can indulge only in an activity that is forbidden by her grandmother, she does eventually become a responsible caregiver to chickens and chicks.

The title provides a clue to the story, which establishes a countdown from the time a little girl and her father see her mother off on a flight to Korea. There the mother will complete the adoption process, and the little girl will have a baby sister. The illustrations portray both the mother in Korea and the little girl preparing her home with the help of her father and grandparents. A calendar shows the countdown, as well as the text, which provides the written number of days and nights left. Colorful illustrations in oil, pencil, and collage show happy faces and a lot of busy activities on both sides of the ocean. An author’s note about Korean adoptions concludes the book. For a story about a baby girl adopted from India, with the father flying over, see Uma Krishnaswami’s Bringing Asha Home (Lee & Low, 2006). My Mei Mei by Ed Young (Philomel, 2006) portrays the adoption of a baby from China.

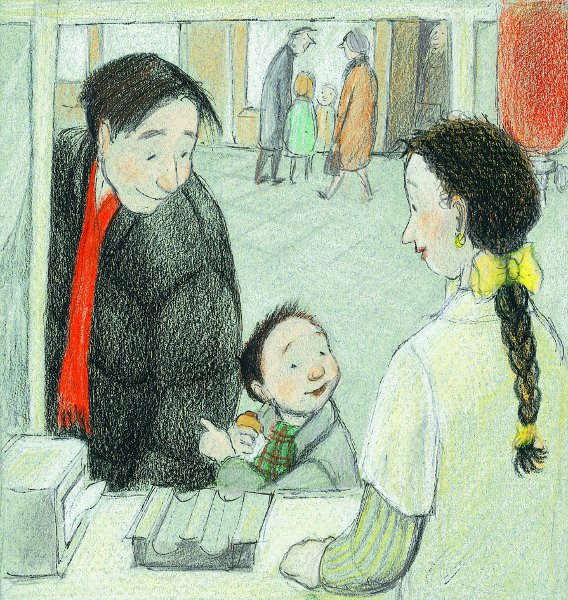

A young boy of divorced parents makes the transfer between his mom and his dad at the train station. When his father arrives, they immediately plan their day. As they go from a hot dog stand to a movie to a pizza place to the library, the mood is happy. A wonderful portrayal of the love between father and son, this story evinces no sense of abandonment but acknowledges that time together is short. The illustrations, in colored pencil, always show the father and son as the center of attention in each drawing. (See figure 2.2.) Colors are muted, as if in a memory being savored, although Dad’s red scarf stands out in many of the drawings. A comforting, reassuring story for children who do not live with their father.

Figure 2.2. A Day with Dad

A couple of dogs are not happy that a new baby has joined their human family. Missing the special attention they once received from the grown-ups, one of them contemplates what they could do to the new little one, but the other one wisely deters her. Eventually they become protective of the baby, not letting Grandpa, whom they have never met, near him. Full of gentle humor, the text shows from a dog’s point of view what it is like to deal with an intruder. The colorful illustrations emphasize the baby as the center of attention, with the parents always surrounding and leaning over him. At the end, the two dogs and baby are on the couch, obviously at home with each other, but then turn the page and see that Mom is pregnant again, and readers can speculate about who will be unhappy next.

Full of love for his grandma, a young boy describes her and her activities around the house. With colorful illustrations made from a variety of materials, including clay, fabric, wood, and metals, the book is a visual delight. Throughout the narrative, Spanish words pop up as Abuelita cooks breakfast, dresses, and prepares for work. Although her work is alluded to throughout the story, not until the last page do readers find out what it is. So many positive emotions and attitudes combine here: love between a grandmother and grandson, pride in one’s appearance, keeping in shape for one’s work, and enthusiasm for life. From little Frida Kahlo the cat to Abuelita’s fuzzy robe to her bumblebee towel, there is much to smile at in this story.

The love of a grandmother for her grandchild fills this book with an atmosphere of tenderness and care. Set in Hawai’i, with some Hawaiian words and traditions employed, the story features a grandmother who tells her granddaughter how beautiful the child is and has been from the day she was born. Watercolor illustrations, bright with the color of sun-drenched islands, focus on the two main characters, although other villagers, animals, and vegetation appear. Their gentle lyricism matches and expands the text, which features poetic elements and back-and-forth dialogue. End material includes a glossary of Hawaiian words and a string design that children can make, similar to a cat’s cradle. Complement with Denise Vega’s Grandmother, Have the Angels Come? (Little, Brown, 2009), which also contains alternating dialogue and charming illustrations, but which focuses on the grandmother’s appearance.

The love and security of the grandparents’ home comes through in this story of a child visiting their house, and what happens at the kitchen window. As the child describes the kitchen and what Nanna and Poppy do there—play the harmonica, count the stars, make breakfast—the everyday activities create an atmosphere of love. The energetic and colorful illustrations appear childlike in their simplicity yet project a masterful combination of color, line, space, and mood. A special story about a special window, which represents the fun and feeling shared by a child and her grandparents, this book was the Caldecott Medal winner in 2006. Nanna, Poppy, and their granddaughter return in Sourpuss and Sweetie Pie (Michael Di Capua/Scholastic, 2008).

When her mother insists that Rubina take her little sister along to a birthday party of one of her classmates, Rubina just knows that this is not the way it is done in their new country. She feels embarrassed and, as she fears, little Sana makes a scene. Even worse, Sana steals her red lollipop, a treat which she has been saving from the party. The text, in first person, allows the reader or listener to feel Rubina’s conflicting emotions of excitement and chagrin. Some illustrations put the characters at center stage, with (on most pages) very little or no background. Several illustrations show movement with lines of motion or direction; one, in which Rubina runs from her school to home, shows the blocks and sidewalks behind her, and another, where Rubina chases Sana through the house, looks down from the top at the pieces of furniture and rugs. When time passes and Sana receives a party invitation, her mother insists that she take the youngest sister, Maryam. Rubina remembers her experience and talks to her mother, a satisfying ending to a very realistic story about sibling rivalry.

How does an author get inside the head of a character, especially one with a great imagination? Lammle’s portrayal of young June is pitch-perfect. Before she can do all the fun things she dreams up, June must finish a list of chores. With a little help from a bird, a dragon, and under-bed monsters, she finishes her tasks. Illustrations in watercolor and pencil portray June and her fantasies in comical fashion. In some cases, the creatures become as large as she is. This and the list that towers over her head contribute to the feeling of being overwhelmed by her chores. Dialogue balloons pop up in several scenes as June addresses her imaginings and her mother brings her back to reality. This adventurous girl (check out the goggles and flashlight) is a character to amuse and inspire.

With rhyming and minimal text on each page, this story follows a cat and his daytime activities. His nighttime activities, however, remain a mystery until the last page. Young listeners will enjoy the cutouts on certain pages: a mouse hole, two circles to see the cat’s eyes, and diecut pages that become a moon and a blanket, among other items. The artwork illustrating Tippy’s daytime perambulations features bright colors in sunny yellow, orange, and green. The nighttime scenes shimmer with a pale yellow moon and textured blue sky that spills over into blue fence posts and blue blankets. A fun bedtime story for family read-alouds, this book would also be useful for teachers planning lessons on time or night and day.

This story of a grandparent with memory loss, handled gently and respectfully, focuses on her relationship with her grandson. The rhyming text recounts incidents of her misplacing objects, losing her way, and calling the grandson by his dad’s name, but it also describes how the grandson helps her. The illustrations, in watercolor and ink, display a delicateness and detail in a mixture of indoor and outdoor scenes. Far from being sad, this story told from the point of view of the young boy is rather matter-of-fact. For another take on this subject, but still with grandson-grandmother characters, see A Young Man’s Dance (Boyds Mills, 2006) by Laurie Lazzaro Knowlton. For a granddaughter’s point of view, see Robin Cruise’s Little Mamá Forgets (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2006) and the Belgian import Still My Grandma by Véronique Van den Abeele (Eerdmans, 2007).

A wedding in the family should bring great joy, but one little girl is not happy. In first person, she takes the reader through the whole day and expresses her displeasure at what she feels is her uncle’s abandonment of her. Along the way, she explains many Chinese wedding traditions. Her words, which express her emotions and describe the customs as a young girl would, are enhanced by the oil paint, pencil, and collage illustrations. The cartoon-style artwork fills up each page with all the objects she describes and all the people at the wedding, including a large extended family. Despite her attitude, the story does not turn negative but instead reveals both her openness to express herself and the many traditions she explains. At the end, Uncle Peter’s new wife finds a way to connect with his niece, and it all ends on a happy note.

With beautiful language, Lowry tells a story based on her girlhood in which she ventures out with her father, newly returned from the war. Tentatively, she reconnects with him, eventually confiding her fears and reveling in a shared sense of humor. Realistic illustrations of watercolor and acryl-gouache complement the narrative visually with emotion and period detail. Although set in the 1940s, this story will resonate with any listener who shares, or wishes to share, quality time with Dad. The outdoor setting will appeal to many, and the notion of calling the crows with a whistle may be new to almost everyone. Read this lovely father-daughter story and revel in the superb use of language by a master storyteller.

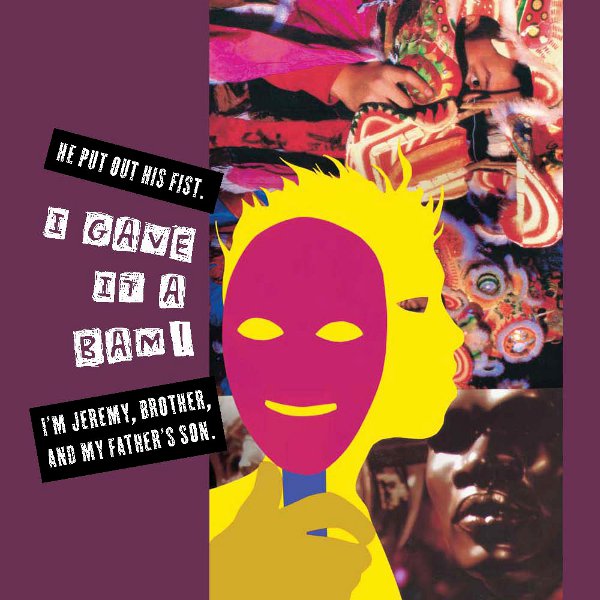

With energy and poetry, with vibrant color and exuberant line, this book celebrates being proud of one’s self, one’s place in the family, and one’s place in the world. The father-and-son team who wrote and illustrated this book have given a gift to all young people who read it, especially boys. Jeremy, the main character, receives affirmation from his sister, father, teacher, grandmother, friends, and mother amid a swirl of saturated color, silhouettes, and photographs. The rap-like rhythm of the words encourages reading out loud; at the same time the words call for thoughtful contemplation. The collage illustrations invite exploration. (See figure 2.3.) This would be an excellent source to use in art classes of all ages. The book ends with a page about the author and illustrator that contains small pictures of the young Walter and Christopher surrounded by words describing them.

Daniel has a problem. His family must take care of his aunt’s dog, but Daniel is afraid of dogs, even though he will not admit it. Although he tries to hide from Bandit, he forms a bond with the pet when he discovers they are both afraid of thunderstorms. The illustrations, in pen and ink with watercolor and gouache, capture Daniel’s fear of dogs, his stubbornness, and his eventual realization that the dog is more fearful than he is. The realistic text gets Daniel’s dialogue just right, as he insists that he is not afraid, he just does not like dogs. At the end, of course, he completely reverses his opinion, and even lets Bandit sleep in his bed. A book of comfort to those children who may be afraid of dogs, and a feel-good book about man’s—or boy’s—best friend.

A young boy imagines what his parents are up to while he and his little sister visit their grandparents. Everything he envisions, hilariously illustrated in watercolor and colored pencil, is something that he obviously has been told not to do, such as jumping on the bed with shoes on, sitting too close to the television, and playing basketball in the house. The text even contains his words of disapproval, which sound exactly like something parents would say. While Mom and Dad inhabit the main illustration on each page, small scenes of the boy and his sister at the grandparents’ house provide a counterbalance, as they do the right thing and still have fun. Parents who share this book with children will chuckle in recognition, and children will appreciate the misbehaving antics of the grown-ups.

A young boy moves from a house to an apartment, but this story is told from the point of view of his pet cat. In first person, the cat remembers what was, and how it is now so different. No back story is provided to explain why the move has occurred, but certain words that appear in the text (misery, quiet, tossing and turning) and the boy’s somber look in one of the early illustrations make it seem that it was not a happy one. But, as often happens, a new day brings a fresh perspective. The cat discovers that birds still fly outside the window, that this new place also has lovely hiding places, and that his boy still comes home to him. Realistic watercolor artwork features large illustrations of the cat, the boy, and other objects in the home, making readers or listeners feel as if they are there.

The twisting roads around country sites that fill the endpapers provide a preview to what readers will find inside this story of a stock family experience: the Sunday drive. A family—Mom, Dad, three kids, and a dog—take a trip with no real endpoint. They stop at various places along the way, driving down curving roads in a beautiful countryside portrayed in acrylic illustrations. A combination of full two-page pictures, bordered one-page illustrations, and smaller scenes in circles provide variety. Told in first person, the text reads as if a friend is telling about all the fun things he did. The rich colors of the illustrations, the leisurely pacing of the story, and the solid feeling of family combine in this congenial story.

Everyone has had one of those days, and this book names them specifically. With this clever concept, each page, or sometimes a two-page spread, presents the type of day in word and picture. Favorite Pants Too Short Day, Itchy Sweater Day, Can’t Find Stuff Day—see them all here. The illustrations, in paint and ink, show a young boy or girl undergoing the trial of that particular day. Comical drawings and bright colors make the artwork kid friendly. While some of the days are laugh-out-loud humorous, others are poignant. This book would be a great discussion starter on feelings and bouncing back from disappointments. One of Those Days is one of those books that enters into a child’s sensibilities and understands.

How can the concept of time be explained to a child? This seemingly impossible task might be just a bit easier if this book is used to describe “a day.” With rhyming text, Rylant makes clear how a day’s newness signifies hope and that anything can happen. McClure’s illustrations depict a young boy in a country setting, with chickens and a garden, with dandelions and a hammock, with walks in the woods and a sudden rainstorm. (See figure 2.4.) An artist’s note at the end explains the process of making the cut-paper illustrations, including how the colors—alternating gold and pale blue with each page turn—were added by computer. The overall scheme of black and white with just one color combined with the unique illustrations is beautifully spare on some pages and remarkably detailed on others. Altogether, it evokes moods of happiness and satisfaction, which work well with the poetic text. In the last scene, the little boy walks toward the rising sun, shovel over his shoulder, ready to meet the new day as the text encourages listeners to seize the day and make it their own.

What is real, and are there situations where it just does not matter? A big brother figures this out when his little sister tells the family that pink monkeys now live in the refrigerator. Everyone else in the family—Dad, Mom, and older sister—go along with Maggie’s notion. But her brother keeps reminding everyone that the monkeys are not real. Told in first person from his point of view, the story builds on his frustration with his family and their acceptance of these monkeys. But one day, when his friends visit and start teasing Maggie, he comes to her defense and stands up to his friends. With every question they ask, he counters with the answers that other members of his family have given him. Illustrations, in black colored pencil and gouache, portray the family in cartoon style with bright colors. The brother’s frustration and the other family members’ benign acceptance come through clearly and humorously in the artwork. An impish twist: some of the illustrations feature a pink border; some of these include a little pink monkey crawling along the side or perched on top. This is a lively story about family loyalty and the magic of imagination.

Shannon’s signature humorous situations and giddily goofy illustrations make this book a delightful experience for children and adults. When Spencer’s mother finally reaches her limit with the mess in his room, she insists that he get rid of some of his toys. And who can argue with her? Just about every page bursts with toys of all kinds. Glorious color and realistic text detail what types of toys Spencer plays with and where the toys came from. Two scenes of special note: Spencer giving his mother the big-eyed, aw-mom look when she dares to try to throw out a dirty old stuffed bunny, and Spencer in an office setting as he argues his case to negotiate a deal with his mother for keeping the toy train. Genius! Adults will laugh with recognition, and kids will relate to Spencer in this slice-of-life adventure.

Considering its big size (9.5 by 13 inches), its huge type fonts, and its over-the-top braggadocio, this book has the perfect title. A look inside the head of a boy who has been placed in the corner of his classroom, the story features his imaginings: from taking over a business meeting, to winning a football game, all the way up to being the president and then an astronaut. The mixed-media and collage illustrations complement perfectly the wacky, no-holds-barred nature of the story. Anyone who secretly has dreamed of being the boss of everyone will enjoy this book.

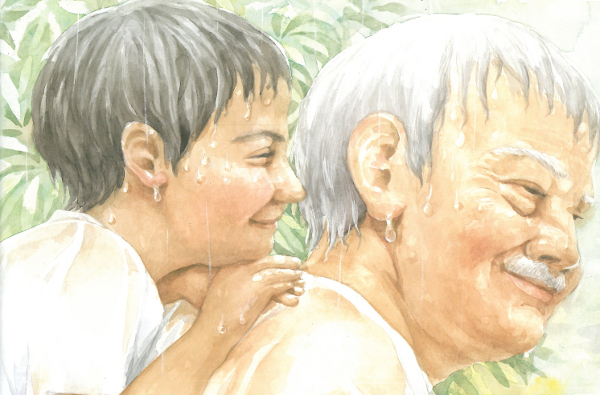

A young boy in India finds a willing playmate in his dadaji—his grandfather—on a rainy afternoon. They race boats, watch a peacock, visit the banyan tree so the little boy can swing and pick mangoes. This sweet tale transcends nationalities as it portrays the love between a grandson and grandfather and the simple joys of playing and observing nature. (See figure 2.5.) The two also talk about what the grandfather did as a young boy and imagine what the present little boy will do when he is a grandfather. When his grandmother scolds them for tracking in mud, the boy and his grandfather even take on the same sheepish expression. The watercolor illustrations, soft and muted, reflect the rainy day. Their view of an Indian street, courtyard, and house will be interesting for children who are just learning about cultural differences.

What can a boy do when his mother insists that he does not need a dog and that his goldfish is just as good a pet? The first-person narrative lends immediacy to his story; he also throws in comments on the feelings the characters portray—sad, irritated, hopeless—which are then reflected in the illustrations. Overall, a mood of humor comes through as son and mother trade reasons for and against, and as the boy tries to treat his goldfish like a dog. The illustrations, rendered digitally, are spare and modern looking. The round heads of the characters match the round goldfish bowl, round goldfish, and round head of the imaginary pet. A delightful charmer of a story over a familiar battle. Supplement with Emma Dodd’s What Pet to Get? (Scholastic, 2008), where a little boy comes up with all kinds of wild ideas that his mother shoots down; You? by Vladimir Radunsky (Harcourt, 2009), where a girl finds a pet in the park; and Fiona Roberton’s Wanted: The Perfect Pet (Putnam’s, 2009), in which a duck convinces a boy that he is ideal.

Just as the title promises, this story features a chicken who insists on interrupting the bedtime stories that her papa tells. One after the other, favorite tales such as Hansel and Gretel, Little Red Riding Hood, and Chicken Little do not make it past the second page, as the chicken bursts in with words of warning to the storybook characters. The illustrations—in watercolor, crayon, china marker, pen, opaque white ink, and tea—abound in reds, greens, and blues and feature the characters with exaggerated heads and tail feathers. The pages that open up to the storybooks depict an immediate change; not only the fact that an open book is pictured, but the illustrations change to muted colors and a limited palette. So when the little chicken literally enters the story, her bright colors contrast. The repetition of the three stories with three interruptions leads to the little chicken writing and illustrating her own story, done in childlike drawings and letters. A sweet ending finally brings rest in this story of a familiar bedtime ritual. Another animal that likes to interrupt stories, this time a dog, stars in Peter Catalanotto’s Ivan the Terrier (Atheneum/Simon & Schuster, 2007).

A poem by the famous nineteenth-century author Stevenson forms the text of this picture book. The watercolor-and-ink illustrations depict a young boy going out for a nighttime boat ride with his father. At first glance, the story told in the pictures has little to do with the poem, but each line contains elements reflected in the illustrations. A mood of adventure and fun permeates the trip out to the boat, the boat ride, and the trip back home. The moon appears on every two-page spread, except for the very last, when morning has come. Sharp eyes will notice that in that scene the little boy runs to his parents with the book The Moon. An excellent example of illustrations complementing text, with neither explaining the other, this book could be used as a learning opportunity for poetry. This might even be one that children will memorize on their own with enough repeat readings.

More than just another pesky little brother story, this book combines the bothersome brother with the creativity of the writing process. Lizzie loves to make up stories, and when her little brother, Marvin, comes along, he becomes part of her plots. Although he is a pain, he unwittingly helps her overcome her writer’s block. Everyday scenes of school and home life take on a charming cast with humorous illustrations and stories within the story. Little extras like Lizzie’s special Princess Merriweather pencil and Marvin’s many messes add to the giggles. The text makes clear the writing process, including its highs and lows, and brings home the point that stories are best when shared.

A comforting reverie about home combines with fantasy, as a girl flies on the back of a bird over her town and up above the moon. The rhythm of the text makes it a delight as a read-aloud. A wonderful example of precision of language, the text combines seamlessly with the detailed illustrations. With three colors—black, white, and gold—Krommes provides the reader with the whole world from a single room to outer space. Each of the double-page spreads contains one or more objects of the bright color, highlighted in the scratchboard illustrations. This book was a Caldecott Medal winner in 2009. Readers may feel its kinship to Margaret Wise Brown’s Goodnight Moon, as well as the cumulative story of The House That Jack Built.

Charlie, who always imagines the worst, believes in being prepared. Viorst’s text humorously details his imagined fears and his sometimes over-the-top preparations, such as digging a pit in his yard for a lion that may get loose. The illustrations in mixed media match the gentle humor in his imagined scenarios and his complicated preparations. In the end, a surprise birthday party truly takes him by surprise—it is one situation for which he has not prepared. The sometimes crazy things Charlie does will appeal to children, who will identify with his worry and with his imagination. The illustrations, presented simply with lots of white space, feature bright colors and incorporate collage. A good choice for read-alouds or for one-on-one sharing.

Telling a story within a demanding form is difficult; Wardlaw makes it look effortless as she uses senryu, a form of Japanese poetry. Like haiku, senryu is a poem of three lines, with five syllables in the first, seven in the second, and five in the third. Clearly expressed, Won Ton’s journey from an animal shelter to a new home shows humor, attitude, and growing affection for his new family. Illustrations rendered in graphite and gouache on watercolor paper offer spare visuals—usually just Won Ton and an object or two on each page—which coordinate beautifully with the text. The endpapers feature a great expanse of cat fur that matches Won Ton’s grayish blue fur throughout the book. Besides being a heartwarming story of a rescue animal, this book is an excellent supplemental source for the study of haiku and senryu for any age group.

The truth that Sophie feels compelled to tell concerns babies. This humorous look at being a big sister is told in the first person, accompanied by illustrations that go beyond the words in expressing how perfectly awful her little brother is. The text includes lots of large, hand-drawn words and phrases that convey Sophie’s disgust and exasperation. The cartoon-style illustrations, in India ink and colored digitally, come on strong, just like the title character. An articulate big sister, Sophie reveals her irritation but eventually finds that she does like the little guy. This book will appeal to all kids who think their younger siblings are monsters. Pair with How to Be a Baby—by Me, the Big Sister (Schwartz & Wade, 2007) by Sally Lloyd-Jones. See this plot turned upside down in James Solheim’s Born Yesterday: The Diary of a Young Journalist (Philomel, 2010), in which a baby explains her sister.

No place is quite as comforting as a grandmother’s house, as the girl in this story discovers when she is faced with moving to yet another new place. She recalls her family’s previous three houses and wonders at her parents’ need to move again. Enveloped in the love of Grandmom, she relates the things that they like to do together revolving around the grandmother’s house and its importance to her. The lovely watercolor illustrations pick up this theme with scenes of the girl and her grandmother gardening and cooking. Grandmom’s comments reveal her to be feisty, a positive thinker, and loving toward her grandchild. This story and the impressionistic illustrations wrap the reader in a blanket of a grandparent’s love.

Sibling rivalry before the new baby actually arrives is not uncommon. In this story Gia resents the coming baby whom everyone, it seems, cannot stop talking about. Even her friends’ jump rope rhymes are about babies. Notice Gia’s size in some of the illustrations where she is feeling especially crowded out by talk of, and preparation for, the new baby. Ink-and-watercolor illustrations depict an African American girl and her mother, with multiethnic school friends and relatives. This story sweetly captures the mixed emotions of a big sister who feels her relationship with her mother will be changed forever.

For all those girls going through the princess phase, this book reinforces the idea that girls can play sports, get dirty, fix things, and enjoy many fun activities. They may still wear their princess crowns, but they also dress in sports jerseys, jeans, overalls, and bike helmets. The delightful digital illustrations feature a diverse collection of active girls, all with their crowns. Teachers, librarians, and parents may want to use this story, a nice antidote to the plethora of pink, to let both girls and boys know that many facets to one’s personality and many different interests can coexist. The rhyming text comprises between two and four lines per two-page spread, which keeps the story rolling along to the final scene, a royal ball with all manner of clothes—but no pink! Pair with Mary Hoffman’s Princess Grace (Dial, 2008), in which Grace and her classmates learn about real princesses throughout history and the world, shattering several stereotypes.