Out in the World

The picture books in this section move the story outside the circle of family, friends, and school into the wider world. Readers will encounter new cultural experiences, recognizing that everyone is a global citizen. They will also develop an awareness of history and a sense of continuity by learning that others came before.

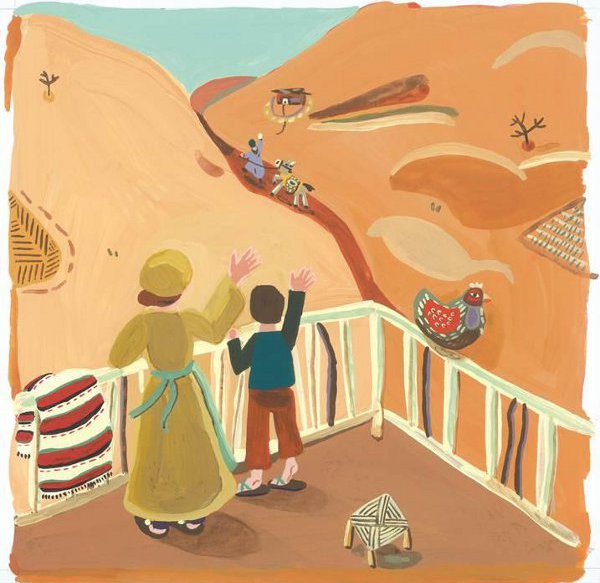

The authors evoke the keenness of hunger and the satisfaction of satiety, which become the underlying conflict in this story. A young girl’s baba—her father—tells about his childhood while he prepares an evening meal of couscous. Travel to Morocco in this story within a story, where his mother finds a way to take her young son’s mind off their lack of food by telling him to wait for the butter man. Full-page gouache illustrations face each page of text, the colors reflecting the landscape of a drought-stricken country. (See figure 4.1.) The font size of the first line of text in the book is larger, as it is in the first line of the story that Baba tells and in the return to the present day, signaling these changes in time and perspective. An author’s note and glossary assist with understanding the geography and culture of the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco.

The century-old hymn of the title provides the majestic words illustrated by stunning collage art. Bryan used his mother’s sewing and embroidery scissors to cut the brightly colored papers that take the shape of people, animals, and objects in this book. Layering the pieces creates the depth; delicate cuts give texture to the compositions. Each page provides an abundance to look at, either by one reader or in a group. Art teachers may want to use this as a preliminary read before embarking on older students’ construction paper collages; inventive ideas for portraying water, wind, people, and vegetation abound in this beautiful book.

The storm of the title refers to both thunderstorms, which scare young Hallie, and the storm of buffalo hooves as they thunder across the prairie. She deals with each as she travels west with her parents to Oregon in a covered wagon. The text, in first person, stays true to a young girl’s feelings as she leaves her beloved grandmother and faces the challenges of a long journey. Watercolor-and-pastel illustrations also capture the emotions of the characters and offer some exciting scenes, especially when Hallie falls out of the covered wagon and when she rescues a buffalo calf. The double-page spread of the running of the buffalo herd pulses with power and strength; the dust that surely obscured them in real life shadows over the great brown shapes. A strong female character who overcomes fears and worries shines through in this pioneer story. Partner this with Jean van Leeuwen’s Papa and the Pioneer Quilt (Dial, 2007).

Follow along on the migration of a buffalo herd as it traverses the prairie, and see the role the old buffalo takes on as protector of a newborn calf. Combining fiction and nonfiction allows the story to present facts about this magnificent animal and the cycle of life while concentrating on the engaging story of one character. Large watercolor illustrations capture the colors of the landscape and the times of day as well as the great brown animals. Especially dramatic is the transition from a long view on one page to a close-up of the buffalo’s face that completely fills the next page. Listeners should look carefully on each page for other, smaller animals that appear. Ideal for group read-alouds, this book would be a perfect supplement to science or social studies curricula. The text, forthright yet moving, combines with realistic illustrations to provide a wonderful introduction to a piece of the American past.

Reflecting an important part of its plot, this book is structured as a silent movie: in black and white, with frames of action and with limited phrases to give needed information. Incredibly detailed ink on clayboard illustrations play up the melodramatic mood of the story, which concerns an immigrant family from Sweden and their trials and triumphs in New York City. Partner this with some Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, or Harold Lloyd movies, especially with older children. The author’s and illustrator’s notes present a personal look at the creative process behind this unique book.

Parallel stories take place in this book about cooperation and friendship. One story involves the zebra, wildebeest, and gazelle that share the grazing lands in Kenya. The first few pages illustrate how each animal eats only the top, middle, or lowest sections of the grass. The other, more personal story features two boys. Abaani, of the nomadic Maasai people, cares for his family’s cattle, while Haki, a Kikuyu boy, helps his family sell the vegetables grown on their farm. At first the boys yell hateful phrases at each other, words they have heard from others in their tribes. But one day, they come together to rescue a baby from angry warthogs and so begin a tentative walk toward friendship. By the end of the book, they talk, play games, and trade vegetables for milk. Recalling the beginning, the ending compares the boys’ sharing to the animals’ sharing of the grass; thus there is hope for the future. The ink-and-watercolor illustrations depict the grasslands, cattle pens, and roads of the Kenyan countryside, as well as the people and animals. An author’s note concludes the book with more information about the Maasai, the Kikuyu, their rivalry, and the game of mancala that the boys play. A glossary with pronunciations is included for unfamiliar words and phrases.

With a quiet sense of anticipation, this book portrays the cold darkness deep in the forest, where the animals await the coming of morning. Watercolor illustrations, which reveal the largeness and wildness of the animals, consist of dark blue, green-blue, and brown until the last five pages. As the sun comes up, pale pink and yellow filter through the branches as the transition to daylight becomes complete. The text presents as a prose poem, with the crow, moose, and fox offering to find the hiding sun and wake it up. But finally it is the tiny chickadee that brings the sun back. Young readers and listeners will love the large, up-close illustrations of the forest animals.

When aviator James Banning and mechanic Thomas Allen flew across the United States from Los Angeles to New York in 1932, they encountered ridicule, mechanical difficulties, bad weather, and prejudice. For they were the first African Americans to make a transcontinental flight. Illustrations that capture the emotions of the main characters give this story its personal feel within the context of history. The text brings forth their determination in the face of many obstacles, as well as the adventurous spirit that kept them going. The book puts readers in the seat of that early aircraft to make them feel the heat and the wind, to see the scenery of America, to feel hunger when they were not allowed to eat in restaurants, and to hear each other call “Hallelujah” whenever they made a good landing. This fictionalized version about real people and a real event will introduce Banning and Allen to children for whom this story will be an inspiration and a high-flying adventure.

Looking for heart-pounding action? This story, set in the wilderness of Alaska, brings it on—with intensity. A bear attacks a boy and his father. Pa, with a broken leg, sends Johnnie and his dog, Swift, off for help. A snowstorm, a fall in a river, and that now-wounded bear are just a few of the terrors they must face. Realistic oil paint illustrations capture the forest and tundra, as well as the pain, cold, and fear. Endpapers showing the routes taken by Pa and Johnnie will appeal to listeners who enjoy maps. Those who oppose hunting may not be able to get past the scenes of both the boy and his father with guns, but those who are willing to accept this reality of the setting will find a story of faithfulness, growing up, and the human-animal bond. The author’s note at the end recounts his experience with, and information about, homesteading families in Alaska.

Imagine going from a smoky and drab cityscape to a green and flowery one. That progression happens from the first page spread to the last in this story of Liam, who decides to take care of a few plants. He starts small, watering and pruning the sad specimens on an abandoned railroad track. But soon the garden spreads, and eventually other people join in and transform the city. The illustrations, acrylic and gouache, range from small, quarter-page, and unframed, to multiple framed illustrations on a page, to full two-page spreads. Several pages show the expansion of the garden with illustration only. The text, quiet and matter-of-fact, reflects Liam’s personality. The illustrations add information, such as Liam singing to his plants, which is not explicitly stated in the text. The change of seasons occurs, and even winter keeps the hero of the story busy with plans for planting in the spring. Brown adds a touch of whimsy with the illustrations of topiary animal shapes. A must-read for gardeners and conservationists who hope to pass on their love of growing things to a younger generation.

This book takes a fictional look at historical fact—the building of the Golden Gate Bridge—witnessed through the eyes of a young boy whose father works on its construction. He and his friend, Charlie Shu, whose father is a painter on the bridge, observe its construction, a terrible accident, and its completion while watching over their fathers with binoculars. The illustrations, full one- and two-page spreads, show both the scenes of the huge project and the up-close emotions of the boys. The faces of these characters, plus others in crowd scenes, offer fascinating detail, capturing the feel of the 1930s. The first-person text perfectly blends the personal—a son’s pride, worry, and elation—with the big picture. Fascinating perspectives, such as the reflection of the bridge in the binoculars in one such scene, make the illustrations noteworthy. A note from the author with further information about the construction of the bridge concludes the book.

First published in France, this captivating book takes readers to China, where Master Yang rescues an abandoned orphan. Lyrical storytelling combines with magnificent illustration as the young boy discovers that his guardian is a master of eagle boxing, a form of kung fu. The boy becomes Little Eagle, training with the master for years. Gorgeous art depicts all phases of his life; an especially evocative series over two pages displays the exercises he performs during each of the four seasons, each in a different hue. As the master ages and the two enter into battle with their enemy, the action peaks. It ends as one generation passes on to the next. The large size of the book makes it a natural for reading aloud, although children who are into any of the martial arts will enjoy paging through it on their own. Follow the real eagle throughout the book, his presence a symbol of courage and discipline.

Beautiful woodcut illustrations lend an old-fashioned feel to this fictional story of a young woman who leaves her home in 1856, travels to a new land by boat, and builds a life for herself, all with the help of a shovel. The cover illustration portrays the title character setting off with shovel in hand, and every illustration throughout the book includes the shovel. Each illustration is bordered in black, with the text outside of the border or, in some cases, in a black-bordered box within the illustration containing and picking up the black outlines of the woodcuts. This book could be used as supplementary material in social studies, with its scenes of life from the second half of the nineteenth century. Emigration, a woman’s life span from teenager to grandmother, rural living, love and loss—all these themes combine in this rich story.

Readers and listeners will almost feel the heat of the atmosphere in this story, in which a Kenyan village teeters on the verge of drought. Lila worries, especially after hearing her mother talk about consequences of no rain, so she consults with her grandfather. Acting on a story he relates, she climbs to the top of a mountain and begins to tell the saddest things she knows. With a welcome onset of rain, the people of her village celebrate. Dry-dust browns dominate the illustrations, with a large golden sun in the daytime pictures. The reader views the scenes as if from far off, enhancing the feel that this takes place far away. Stories told by the grandfather and Lila appear in gray with splashes of red, providing a contrast to the warm colors of the majority of the illustrations. The text, beautiful in language, gathers the reader in and makes the ending believable. In combination with the art, it becomes a total package that will transport listeners to the African desert.

Interesting perspectives make this illustrated story of a day at the beach memorable. Taking the long view, the artist shows the beach gradually filling with people at the beginning and emptying out at the end. In between, small watercolor-and-pencil illustrations, sometimes more than two dozen to a page, illustrate sunbathers, swimmers, animals, clouds, boats, and more in what is almost a sketchbook of all that an artist can observe. It is as if that artist were sitting on a hill looking at the beach and painting, giving a plein air feeling. While the drawings exhibit an undetailed, almost unfinished look, they go well with the text, which is detailed in its observations, except for a few pages that are wordless. The large-size format of the book affords plenty of room for all the illustrations, lots to look at, and a good size for sharing with a group.

All the major faith traditions follow some version of the Golden Rule, and in this story, a young boy, in talking with his grandfather, discovers what this is and how to put it into practice. Impressionistic illustrations incorporating the symbols of various faiths provide a thoughtful and rich visual experience. Drawings of angels, animals, Hindu gods, Madonna and child, and decorative elements surround the boy and his grandfather. Especially moving is their dialogue about war, when soldiers and knights and airplanes in moody black-and-white sketches fill the two-page spread. A wonderfully evocative introduction to this concept for the young. Christian, Jewish, Islamic, Hindu, Buddhist, and Native American forms of the Golden Rule are included.

Avi, a young boy who lives in the Jewish quarter, and Hamudi, a young boy of the Muslim quarter, both believe that a white cat who occasionally visits belongs to him alone. When Avi follows the cat one day, he discovers Hamudi, and the two boys argue about ownership of the animal. A rare snow in their city leads them to follow the suddenly missing cat, and they track down her kittens. Muted colors with rich textures capture the streets of Jerusalem and two of its quarters. Note the realistic facial expressions of the boys. An author’s note provides more information about the city of Jerusalem and its inhabitants. A glossary lists pronunciations and definitions for the Hebrew and Arabic words in the text. This beautifully told and illustrated story serves as an introduction to this part of the world and as a story about problem solving.

From the forms of the leaves to the colors and shapes of the pages, this book presents a complete package of the wonders of fall leaves. In Ehlert’s author’s note, she describes her passion for collecting leaves from all over; color copies of them became the illustrations. Her clever positioning turns them into chickens and pumpkins, cows and carrots, as well as the Leaf Man. Exquisite textures and sumptuous colors of orange, gold, brown, and green take the reader into a fall day no matter what the weather outside. The upper edges of the pages, die-cut into scallops and scoops and zigzags, create the mountains, meadows, forests, and rivers of the story setting. The text flows, matching the ever-moving course of the book and the floating Leaf Man. A unique and lovely book to fall into.

A collection of poems, each focused on one animal, make up this gorgeously illustrated picture book. The animals represent many habitats and continents, from the lion that begins the book to the polar bear that ends it. Each two-page spread features one animal and its poem, which ranges from four lines to thirteen. The illustrations—woodblock prints and watercolor—depict the animals large and in motion for the most part. The physical size of the book makes it ideal for sharing in a group setting. A wonderful cross-curricular source, this book could be used in science, language arts classes studying poetry, and nature studies. It is also sure to be a favorite for students who want to look at it on their own and enjoy the beauty of the art and the animals.

Secret meeting locations where African American slaves can worship as they please, free from the eyes of their overseers, become places of refuge and hope in this story. A young boy is deemed old enough to be entrusted as lookout during worship. Through his eyes and ears, readers and listeners see the fieldwork, listen to the old stories, discover a runaway, and hear the singing and prayers for freedom. Expressionistic illustrations in rich browns, greens, and reds convey the experiences of young Simmy and the other slaves. The text focuses on characters, such as Uncle Sol, Simmy’s mother, and Mama Aku, giving a personal touch to history. With its compelling story and informational author’s note, this book would be an excellent supplementary source for social studies. Hush Harbor offers an affecting look at the religious life of slaves, which is not usually covered in picture books as thoroughly as other aspects of their lives.

From late nineteenth-century Texas comes this historical fiction based on a real pioneer woman who took in orphaned baby buffalo, nursed them to health and maturity, and eventually sent them off to national parks and wildlife refuges. Told in first person, the story reveals Molly’s motivation for saving buffalo clearly and with a bit of humor. The illustrations depict the hard work of farming and ranching, the devastation of the buffalo kills, and the heartwarming appearance of the buffalo calves. An author’s note provides information on Mary Ann Goodnight, the real woman behind the story, plus sources for further information.

Based on events in post–World War II Europe, this story captures the excitement and gratitude of a Dutch girl receiving a box containing soap, socks, and chocolate from young Rosie in Indiana. A correspondence between the two ensues, and more boxes arrive for Katje and the cold and hungry people of her town. Exuberant illustrations depict the emotions of the characters; insets of square illustrations, often with handwritten letters, look like photographs that convey what is happening on both sides of the Atlantic. The pages become fuller as the story proceeds, reflecting the bigger, more numerous boxes and the explosion of Rosie’s project to include many other people in her town who want to help. The ending, in which the Dutch people send tulip bulbs to their American friends, is just perfect.

A combination of the serious and the lighthearted, this story puts a fictional spin on the historical cow that traveled with the Union Army. During the Civil War, a young man enlists and his cow follows him through marches and battles and even his hospital stay. Although a lot of trouble, she also provides milk and winter warmth to the soldiers. Pencil-and-watercolor illustrations do this cow justice: she and the men show a wide range of emotions in the variety of situations pictured. An author’s note concludes the book with information about the real cow. And just to remind readers who the most important character is, a painted expanse of textured cowhide makes up the endpapers.

A book about birds. A counting book. A wonderful example of collage illustration. All these descriptions suit Birdsongs, which is framed by the rising of the sun at the beginning to its setting at the end. In between, readers meet ten different species of birds, each of which fills the page—either singly or in a flock—and which voices (in written words) its distinctive sound. The text of these coos and caws and quacks surround and in some cases cover the birds, in a different font size and usually in a different color from the main text. In descending order from ten to one, these sound words and the birds spread over each set of two pages accompanied by a tree, a nest, a feeder, or other habitat. At the end, after the sun sets, the mockingbird appears to mimic the other birdcalls, all of which appear on the page around her. A concluding section called “Feathery Facts” presents information about the birds shown. Large illustrations, full of color and texture—as well as the possibility of some creative sounds—make this ideal for a read-aloud.

From Tobago to Florida, from Ireland to Japan, fishing takes a variety of forms in this collection of poems, which visits thirteen places in all. The words express beautifully the techniques for catching fish, usually a certain type of fish, and in a very up-close manner; the reader or listener will feel as if he or she is right there. The illustrations in impressionistic style match the beauty of the text. The colors include more than the expected blue or green of the sea; colors of sunrise and sunset, plus reds in clothes and lighthouse also appear. Each picture is labeled with the type of fishing depicted (ice fishing, surf casting, spearfishing, dip-netting, etc.) and the place where it occurs. The book concludes with a child and father fishing, a nice personal touch.

Writer George and illustrator Minor, both prolific in their fields, take readers to the Arctic in this story that combines a dreamlike encounter and the stark realism of climate change. Young Tigluk meets a polar bear that seems to want him to follow her. With his grandmother’s help, Tigluk journeys to a remote area of the Arctic Ocean, where he discovers what the mother bear wanted him to find. Beautifully textured artwork depicts the blue-white of snowy skies, the yellow-gray of the polar bear, and different colors of the ocean. The double-page spreads of the ocean journey present moving scenes: Tigluk and his grandmother paddling their kayak in a sunset-orange ocean, a huge walrus with a baby on the shore of a blue sea with pink and yellow sky, and a large polar bear head peeking out of the green water. Beautifully rendered visuals combine with a text that blends an exciting story and timely message.

This book will transport most children to a completely foreign place, both geographically and in life experience. A young boy, a refugee from Somalia, lives in an orphanage in Kenya. He and the other children go to school, yet he often dreams of his former life with his parents and the camels that are so important to their lives as nomads. When a small caravan arrives at the orphanage with books for the school, Muktar finds that his skill working with an injured camel may fulfill his dream of tending camels. A moving story of a young boy, the text perfectly complements the illustrations, oils on canvas, that feature the boys of the orphanage, the teacher, and the camels. Shades of brown and yellow dominate, reflecting the color scheme of the desert, with splashes of red and blue in clothing. Muktar’s dreams, done in shades of gray, lend an eerie atmosphere. Added features include a map of Africa, with Kenya and Somalia highlighted, and a brief author’s note about these two countries, war, and the camels that deliver books.

In this story about the use of quilts in the Underground Railroad, a little girl witnesses her mother sewing pieces together. Her mother explains what the squares mean and eventually sends her daughter off to freedom with the quilt around her. Rich illustrations, rendered in acrylic paint and textile collages, wonderfully express a little girl’s curiosity and her mother’s pain and hope. Many of the scenes are set against a dark background, reflecting the subject and the fact that much of the action takes place at night. The important quilt squares—the North Star, the log cabin, the tree with moss on the north side, and the little girl surrounded by a heart—depict easy symbols for young readers to understand, just as they were for the girl in the story. Don’t miss the endpapers, which consist of pieced quilts. An extensive author’s note and a list of books and websites for further reading close the book. Include with other books on quilts and slavery, such as Jacqueline Woodson’s Show Way (Putnam’s, 2005) and Deborah Hopkinson’s Under the Quilt of Night (Anne Schwartz/Atheneum, 2001).

An excellent example of the action moving from left to right as the page turns, this story begins with a girl’s pet mouse escaping from its box and into a fancy hotel. Brightly colored illustrations feature comical people and detailed settings. As the little mouse runs through the lobby, kitchen, pantry, and more, these crowded rooms supply numerous places for him to hide, and for readers and listeners to search for him. The large size of the book enables the illustrations to take up the bulk of the page, with the text appearing in a narrow strip at the bottom. Every page spread contains a sentence that needs to be completed by turning the page. This device keeps suspense high and the story moving. This seek-and-find book is not too complicated for a younger audience, and the story provides a behind-the-scenes look at a hotel with some agreeable companions. Originally published in Switzerland.

Based on the true story of Henry “Box” Brown, this fictionalized version of his life examines his childhood and young adulthood and the factors that led to his remarkable plan to escape slavery. With the help of collaborators on both ends, he decided to mail himself in a box from Richmond, Virginia, to Philadelphia. His is a sad story, full of separation and loss, and it is told in a way that does not diminish this pain even as it is made understandable to children. Nelson creates haunting artwork, rendered in pencil, watercolor, and oil, expressive in detail and mood-defining use of color and texture. The series of drawings showing Henry in the box being shoved every which way by men on the boat jolts readers with its cross-section view. The contrast of lightness and darkness and use of color is stunning; compare the pages where he sees his family being sold versus the pages where he arrives in the box in Philadelphia. Supplement with another story of a male slave, who runs away aided by the Underground Railroad and his faithful dog, in Elisa Carbone’s Night Running (Knopf, 2008).

A young Afghan girl, en route to a new country and freedom, endures a crowded and at times frightening voyage over the sea. Cutting between that present-day experience and thoughts of the past, readers and listeners learn of Ziba’s life in the mountains: playing and helping, observing her mother, listening to her father, and finally being driven away by violence. This spare text does not go into detail on the war, as it does with other experiences Ziba remembers, respecting the sensibilities and understanding of a child. Evocative illustrations depict the boat ride and Ziba’s memories in richly colored and textured art. (See figure 4.2.) The people, especially faces, are particularly well portrayed. Because of the short length and the child-centered nature of the text, this book could be used to explain immigrant experiences to young children, yet it is deep enough even for adults.

Can a six-hundred-pound behemoth of a pig be considered adorable? In this book, appealing illustrations, first-person (or would that be first-pig?) point of view, and a style that extols the elemental pleasures of dirt baths and vegetable gardens could convince anyone. The watercolor art is remarkably realistic in its depiction of animals, humans, and landscapes. As Hogwood escapes his pen and takes a trip through neighboring yards and gardens, he comments on what he feels, and he reacts to the neighbors and the policeman, who most certainly do not think he is a good pig. Hogwood’s adventure is an excellent choice for classes studying farm animals, or just as a fun read-aloud. Grown-ups can read his story in The Good Good Pig (Ballantine, 2006) by Sy Montgomery, Mansfield’s wife.

Take a trip through Paris at the turn of the last century in this book featuring the delightful illustrations for which McClintock is known. Simon leaves school with his supplies and articles of clothing, which he loses one by one as he and his sister walk home. Each page turn reveals a new scene, including a market, garden, museum, Métro station, and more, which provide crowds of people and lots of places for Simon to lose things. Young readers will have fun finding the missing items in each picture. Adults may be more interested in the explanations at the end of the book about each scene and trying to identify some of the famous people who are part of the illustrations. Although not mentioned in the text, Miss Clavell and the little girls of Madeline appear in one of the pictures. Be sure to look at the endpapers, taken from a 1907 map. Continue the fun with Adèle and Simon in America (Frances Foster/Farrar Straus Giroux, 2008).

Although the title character, named Jim Key, takes center stage in this story, equally important is Bill Key, the man who takes care of Jim and teaches him. A former slave, Doc Bill uses his skills as a veterinarian to care for animals, always stressing that they must be treated with kindness. Jim Key, foal of Doc’s favorite horse, seems to show an uncanny ability to unlock gates and find hidden objects. Over the years, Doc teaches Jim letters, numbers, and colors. Appealing illustrations take listeners through a range of emotions during the events of Doc’s and Jim’s lives. Based on a true story, this fictionalized version portrays Doc’s affection for his horse and his struggle to have both academic experts and the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals recognize Jim’s abilities. Illustrations portray the historical setting (Jim Key lived from 1889 to 1912), but are timeless in their portrayal of the human-animal bond.

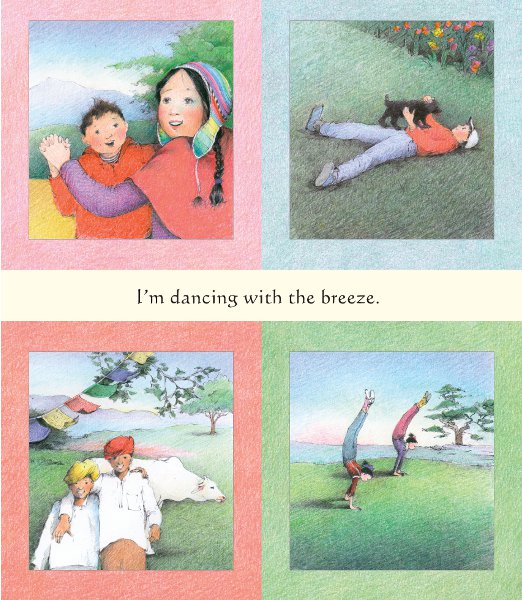

Although children of different countries experience diverse living styles, they also encounter similar feelings and activities. The cover introduces the eight children who appear inside the book. Each two-page spread contains eight squares. Each square illustrates a scene from the United States, Mexico, Bolivia, France, Mali, Saudi Arabia, India, and China. The text, a unifying sentence that begins with “Thank you,” addresses elements of nature, a swing, a window, and a mother that each square depicts. Children may want to go through this book page by page, looking at all the pictures at once, or looking at just one country’s illustrations at a time. With eight on each spread, the pictures are small and intimate, reflecting the child and his or her everyday experiences therein. (See figure 4.3.) The illustrations, in crayon and pencil, can lead to discussions of differences and cultural traditions of each country, as well as similarities. The endpapers again consist of eight squares, each with a globe highlighting the country and its continent or hemisphere. A beautiful book and a springboard to cultural understanding.

With the vigor and loudness that only a large vehicle can muster, a garbage truck tells all. Since this garbage truck works at night, the illustrations emerge in shades of brown, gray, blue, and purple, with yellow illumination popping up occasionally. The text is in your face, with words—and sometimes individual letters within a word—appearing in differing font sizes. In the middle of the truck’s trip, an A-to-Z listing of all types of nasty garbage turns up. Some of these will be sure to elicit laughs from young listeners. The truck is anthropomorphized in the illustrations, a technique that fits well with the first-person text. Both words and pictures portray the roaring power of this necessary machinery. From the front cover, I Stink! comes on strong, all the way through to the back cover, which displays a smaller truck, eyes closed, smiling sweetly. Fans may want to check out the McMullans’ I’m Dirty! (2006), about a backhoe, or I’m Mighty! (2003), featuring a tugboat, or, for dinosaur lovers, I’m Bad! (2008).

A fine example of combining nonfiction facts within a fictional story, this book portrays the migration of monarch butterflies through the story of one butterfly’s journey and her fleeting acquaintance with a tortoise. This story spans October to the next spring, as it contrasts the short life of the traveling monarch and the seemingly unchanging life of the old tortoise. The beautiful watercolor art features close-ups of the two animals, as well as impressive groups of monarchs and the life cycle of egg to caterpillar to butterfly. On the endpapers, a map of North America indicates the migration of the monarchs from Canada to Mexico. An afterword provides more information and statistics about this amazing journey. Compare this with Arabella Miller’s Tiny Caterpillar (Candlewick, 2008) by Clare Jarrett, and Anne Rockwell’s Becoming Butterflies (Walker, 2002), with its school setting.

The shimmering haziness of the illustrations reflects the setting of the story as a young girl helps her father keep watch during the night in a boat on Lake Superior. Language rich with imagery imparts information about sailing and the sea; the first-person narrative describes the emotions of the girl on watch. Hues of deep blue and black dominate the illustrations throughout most of the book, with several pages in green as the northern lights come into view, and then orange and yellow as day begins to dawn. The textured paintings take a variety of views: the boat tiny in a huge sea, the boat large with views of the equipment and people on board, scenes where the reader will feel present on the boat, and others as if looking down on it from above. The overall impression is of movement and cold and watchful waiting. Teachers may want to use this book as an example of descriptive writing before students undertake such an assignment, or for any water- or boat-themed storytime.

Moby Dick has nothing on Cetus, the sixty-ton whale who tries to escape pursuit by Galleon Keene and the wooden boy he carves, Peggony-Po. The Pinkneys have created a seafaring tale with elements of Pinocchio, exuberant in action on the ship and in the water. The young boy’s fictional battle with the whale is set in the 1840s, a prime time for the whaling industry. Illustrations in rich colors portray the whale, the waves, the ship, and the people constantly moving, mimicking a ship-based journey. A rhyming sea chantey offers even more authenticity. The text highlights Peggony-Po’s daring, a great adventure for young listeners. End material includes a note on whales and black whalers, plus a glossary of nautical terms.

With beautiful use of line and color, the watercolor-and-ink illustrations in this story feature the crow of the title, who is indeed little in most of the art. The impressionist illustrations and the poetic text display the essence of the crow and his story. One could hand this book to an aspiring children’s writer and say, “Here, this is how rhyming text is done superbly.” The soft, lilting feeling of the book and its essence of nature, family, and love combine to create a deceptively simple look that hides deeper truths.

Befitting its title character, this book contains some large and loud words. The noises of a lightning storm, tiger, buffalo, and elephant spread across the page in extra-big type to maximize the effect. The illustrations themselves, digitally created, consist of just three colors: black, blue, and light cream. Constant action—running and rolling, swimming and throwing—will appeal to short attention spans. The small size of the elephant on most pages emphasizes his feelings of being alone and not fitting in. The basic story, in which a little elephant separated from his herd finds a group of animals to live with, is simple but affecting. Originally published in India.

The big guinea pigs of the title exist in a story that a mother guinea pig tells her little one. As she relates it, huge, sharp-toothed guinea pigs lived in swamps in Venezuela eight million years ago. A variety of papers from around the world, including basket weave, cellophane, and hand-marbled, make up the incredible collage illustrations. An extensive note about the art, found on the inside back flap, states the origins (countries and cities) of these materials. The modern-day guinea pigs embody cuteness and fluffiness, while the long-ago ones loom large and scary-looking. The scenes of the modern guinea pigs always contain the basket weave paper, emphasizing their home in a cage. The text provides facts, enhanced by the illustrations, but also contains humorous and innocent comments by the little guinea pig. A bibliography is included at the end. This book blends fiction and nonfiction exceedingly well for the very young.

The book opens with a one-page story of the Grateful Crane, necessary background for the plot, since it is a story that the young boy knows well from his mother’s telling. Jiro and his father pay a visit to a family friend who lives in a house with a large garden. While walking through the garden, Jiro discovers a statue of a crane that he at first believes is real. Hearing the adults gently laughing at him, he walks away, and from there this story takes on a dreamy quality. As in the story of the Grateful Crane, his experience includes a house, a woman coming in from a snowstorm, and the sound of a loom. On every page spread, the text appears on the left side and the watercolor illustration on the right. The real scenes are framed with a white border, while the fantasy scenes take up the whole page with no border. The transition from reality to fantasy occurs seamlessly and naturally, so it is a surprise to the reader when the father, looking for Jiro, wakes him from his dream. His words at the end assure his son that he was not foolish for thinking that the crane looked real. A gently magical story masterfully told, The Boy in the Garden exudes a sense of curiosity and wonder.

Through rhythm and rhyme, the text gives the reader a picture of a summer day at the seashore, a farmers’ market, a storm, a restaurant meal, and a family gathering. Its comfortable feeling of happiness and being in just the right place with loving family members permeates the story. Pencil-and-watercolor illustrations portray modern people, but a comfortable old-fashioned quality makes the pictures timeless. This is a wonderful book to share with a loved child or to read aloud to a group and revel in the rhythmic text. Children who like to pore over pictures for details will enjoy several double-page spreads. A good book for anyone, child or adult, who wants to feel part of something bigger.

With a rollicking rhythm and some mighty fine rhymes, this story of a truck in the country celebrates the animate (farm animals) and the inanimate (trucks). When a dump truck gets stuck in the mud, and the little blue truck gets stuck trying to help, the animals come to the rescue. Gouache illustrations feature the natural colors of farmland: brown, gold, yellow, and green. This makes Little Blue Truck stand out even more. The animals sport a comical look, and the trucks, with eyeball headlights, zip along humorously. No human beings are in evidence, even as drivers. Almost every page contains four lines of text with an abab rhyme scheme, an easy feel to read out loud, and an abundance of animal and truck noises. These “conversation” words—beep, honk, oink, moo—appear in color within the text. The same wonderful rhyme and rhythm, but transported to the city, take place in Little Blue Truck Leads the Way (Houghton Mifflin, 2009).

Lovely prose and illustrations combine in a story that gently encourages goodness in order to repair the world. Based on the Jewish tradition of tikkun olam, the explanation that the grandfather gives his granddaughter about the origin of stars and the purpose of humans is inspiring. Because the book is set for the most part at twilight and night, the colors, rich in shades of blue and purple, deepen as the story progresses. The color scheme also includes greens, which fit in with the environmental message, an important part of the story. This gentle book is full of affection and hope.

Although the title seems counter to the obvious cold of winter, this picture book explains why winter is warm, from a child’s point of view. With warm clothing, animals hibernating in dens, and hot food as examples, the book makes the point easily. The illustrations, in acrylics, exude richness and warmth and follow through on the imagery of the text. Some illustrations show a contrast between summer and winter, such as the swimming pool and the bubble bath, but most show winter scenes filled with fun or cozy images of snowmen and hot chocolate and quilts. Recurring shapes of snow drifts, rounded and white, frame many of the illustrations. These round shapes match pictures of puffy jackets, melting cheese on a sandwich, and a curled-up cat. The text includes some internal rhymes and many image-laden words to provide its rhythm and flow. Teachers may want to use this when studying the seasons, while parents may want to do so for a warm and snug read-aloud.

One of the delights of literature is its ability to take a person to a place he or she may never physically visit. This book transports readers to the Himalayan Mountains, where young Kami tracks down his family’s missing yaks. When he discovers an injury among one of the flock, he must go for help just as a hailstorm begins. Because he is deaf and cannot talk, he must use sign to communicate what has happened to his father and older brother. Determined and resourceful, Kami serves as a role model for young children who feel as if they may be too young to make a difference. The illustrations, paintings with almost palpable texture, take the reader to this land of the Sherpas, with its mountains and snow. An author’s note at the end of the story provides information on the life of the Sherpas, their work, families, and homes. Also set in the Himalayas and peopled with children in a Nepali guide family is Olga Cossi’s Pemba Sherpa (Odyssey, 2009).

With bright primary colors and simple illustrations of vehicles, people, and animals, this story follows a truck driver who carries a load of fruits and vegetables from a farm into a big city. Color copies of photographs pasted onto gouache art make an engaging combination of the realistic and painted. Curvy roads, train tracks, construction vehicles, bridges, and stores combine to fill the pages with details for young listeners to examine. At the end, an illustrated list of all forty-seven vehicles appears so that they can be found elsewhere in the book. Almost all the vehicles are very small; thus, many fit onto a page, and their progress along the roads can be shown. The simple language of the text, which may encourage early readers, is upbeat and active, reminiscent of classic Lois Lenski books such as The Little Auto, The Little Fire Engine, and Papa Small.

A newcomer to New York City, Angelina misses her native Jamaica. She longs for the food, the weather, her school, the birds, and the old games; everything in her new home fades by comparison. Her mother discovers that Carnival is celebrated in Brooklyn and arranges to have a beautiful costume made for Angelina so that she can dance in the parade. Winter’s illustrations burst with color throughout, even in her depictions of New York City, but the Carnival dance scenes really explode. Genuine and poignant feelings come through in the first-person text, supplemented by the illustrations that add a depth of emotion to what is expressed on each page. Teachers and parents may want to play some Jamaican music while reading this book.

Based on the true story of the barge that hauled garbage from Long Island down the coast and failed to find a dumping ground, this fictionalized version combines fantastic illustrations with text that begs to be read aloud. Even for those listeners unfamiliar with the states and countries that were part of this event (a great opportunity for learning map skills), the story does a good job of depicting the geographic areas. The illustrations—photographs of hand-built, three-dimensional sets—invite close examination: strange characters, realistic machines, and lots and lots of garbage make them perfect for the almost subversive tone of the text. Regional dialects and phrases will be fun to read out loud. A unique story about a unique event, this book conveys an environmental message with savvy humor.

From the title page spread, with its factories and billowing smoke, and throughout much of the book, a feeling of dark and damp permeates. Black, gray, and dark brown predominate, with flares of yellow and orange that capture the fire in the furnace. This acrylic art meshes beautifully with rhythmic text that describes what happens in a steel mill. A fine example of mixing fiction with nonfiction, this story oozes heat and fire, clanking machinery, and huge buildings. Set in a time of five-cent hot dogs and “Pennies from Heaven” on the radio, this tribute to ethnic families and their hard workers in a steel town shines through.

The sumptuous illustrations will draw readers in, and then the story takes off! And what a story it is—full of suspense, danger, and help from an unexpected source. Told from the point of view of a scarab beetle, the story takes place in ancient Egypt. Hidden in a basket of figs, this scarab is carried to a newly built tomb. There he discovers a stone slab set as a trap for the prince who comes to inspect the place. The action in the text moves quickly, and the illustrations, rich in Egyptian symbol and design, add a visual dimension that helps put everything in perspective. The beetle appears small in most of the pictures, so readers and listeners will have fun looking for it. Balit has beautifully depicted the tomb itself, with its doors and passageways and stone floors, as well as the costumes of the characters. An author’s note at the end provides further information on the Egyptians and their tombs. Gorgeous visuals and a heart-pounding story make this an exciting adventure.

Stunning illustrations featuring handmade paper that looks like leather make this book visually appealing throughout. Each painting of horses in watercolor and gouache is set upon a shirt or dress, inspired by traditional clothing of Native Americans of the Plains. With no more than nine words per page spread, the text captures the power of the horses whose hooves provide the thunder of the title. As these animals and others race across the pages and appear on the clothing depicted, they lend a feeling of power, majesty, swiftness, and color, to the story. A unique book, Ancient Thunder is an excellent source for the study of Native Americans, for art classes, for language arts and poetry, and for children who enjoy stories about horses.

With just a few words on each page and large illustrations, this book is a natural for group read-alouds. A young Native American boy discovers an egg in the forest and brings it home for his chicken to hatch. When the bird comes out with a distinctive beak, the boy names him Hook—and all seem to know that he is meant for flight. After watching several of Hook’s failed attempts to fly, the young boy takes him to a canyon, where the bird finally takes off with wings spread wide. Brown and tan dominate the full-page illustrations, with shades of blues, greens, and reds for contrast. An almost solemn mood permeates the book; this is not a funny “Mother Hen hatches a strange egg” story. From the beginning, even the hen knows that this bird is meant for a higher purpose. The magnificent picture of Hook’s flight at the end features his wingspan, which reaches from one corner diagonally across two pages to the other. This is an awe-inspiring story for animal lovers, budding conservationists, and those who want to hear stories of success.