The Management of Rectovaginal Fistula

Introduction

Rectovaginal fistulae constitute one of the most frustrating conditions to treat. Although not life-threatening, they are associated with significant morbidity that greatly influences social well-being, sexual activity, and overall quality of life. With a limited number of surgeons conversant in its management, patients with rectovaginal fistulae often present to tertiary referral centers after multiple failed procedures.

Almost all reported literature on the management of rectovaginal fistula is made up of individual case series, each with a small number of patients. It is therefore difficult to objectively compare the results of the different treatment options available. The diverse etiology, numerous treatment options, and lack of randomized trials make it difficult to formulate evidence-based guidelines to optimally manage this condition.

This chapter emphasizes the surgical management of rectovaginal fistula and presents broad treatment guidelines based on current reported literature.

Causes

Obstetric injury is the most common cause of rectovaginal fistula. Approximately 2% of all vaginal deliveries are associated with third- and fourth-degree perineal tears, and 3% of these patients will subsequently develop a rectovaginal fistula. Fistulae arising from obstetric injury are often associated with anterior defects in the anal sphincter, leading to some degree of fecal incontinence.

Crohn's disease follows closely as the second most common cause, with 20% to 40% of patients developing either an anorectal or rectovaginal fistula. Rectovaginal fistulas are more likely to be associated with large bowel than with small bowel involvement and can occur in up to 10% of women with Crohn's disease. Rectovaginal fistulae associated with Crohn's disease have a high recurrence rate and often require multiple procedures before healing can be achieved.

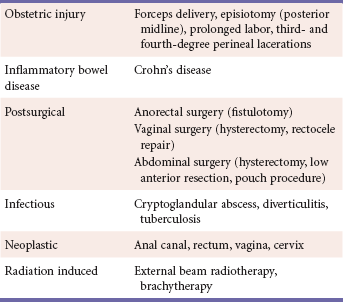

Surgical trauma, anorectal infection, vaginal or anal neoplasm, and radiation therapy for malignancy constitute the other less common causes (Table 1).

Clinical Manifestation

Patients usually present with symptoms of passage of gas or feces through the vagina, although this is often misinterpreted as anal incontinence. Sometimes the clinical presentation may be less obvious, with complaints of a persistent vaginal discharge, dyspareunia, or repeated urinary tract infections.

Because the majority of rectovaginal fistulae are below the level of the sphincter complex, digital examination can often locate the indurated fistulous tract. Meticulous examination with an anoscope or speculum usually reveals the granulation tissue around the opening of the fistula, which can be gently probed to delineate the tract. However, not all rectovaginal fistulas are evident on an initial clinical examination. If a high degree of clinical suspicion exists, a thorough examination with the patient under anesthesia is justified, especially in patients with Crohn's disease, in whom the activity of disease in the rectum can also be evaluated. On occasion, injection of dilute methylene blue in hydrogen peroxide into the primary opening of a fistula may aid in defining the secondary opening.

The goals of preoperative evaluation are to identify the fistula, determine the etiology, and evaluate the extent of the causative pathology and surrounding injuries. Endoanal ultrasonography (EAUS) is an important diagnostic tool to determine defects in the anal sphincter complex, and it can also serve to delineate additional occult collections in complex fistula tracts. Hydrogen peroxide–enhanced transanal ultrasonography has also been advocated to map complex fistulas. Pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and endorectal MRI are useful diagnostic modalities that are especially popular in European countries.

Tests to determine the functional status of the pelvic floor and anal sphincter are indicated if there is a history of sphincter injury or any degree of incontinence. Anorectal manometry to determine sphincter dysfunction and measurement of pudendal nerve terminal motor latency to detect nerve damage are two useful tests to evaluate the function of the pelvic floor. Undiagnosed sphincter injury or pudendal nerve damage could compromise an otherwise successful repair.

After complete workup of the perineum, an evaluation of the entire colon in cases of rectal malignancy, and of the small bowel in cases of Crohn's disease, is mandatory. Thus additional workup could include a small bowel series, colonoscopy, barium enema study, and a computed tomographic scan.

Classification of Rectovaginal Fistulae

Rectovaginal fistulae may be classified according their relation to the sphincter complex as high (above the sphincter complex) or low (at or below the level of the sphincters, also known as anovaginal). The low fistula is almost always caused by obstetric trauma and is often associated with sphincter disruption.

Rectovaginal fistulae have also been classified as simple or complex. Simple fistulae are located in the middle or lower portion of the rectovaginal septum, are less than 2.5 cm in diameter, and are caused by local trauma or sepsis. A complex fistula, on the other hand, is usually greater that 2.5 cm, is located in the upper portion of the rectovaginal septum, and is secondary to causes other than trauma and infection, such as neoplasia, diverticulitis, or inflammatory bowel disease.

Preoperative Preparation

The type of preoperative preparation is largely subjective but usually varies with the type of procedure planned for the repair. For simple advancement flaps, a phosphate enema on the morning of the procedure is usually adequate. For more extensive repairs, such as an overlapping sphincteroplasty or an interposition flap, a full mechanical bowel preparation is preferred. Perioperative antibiotics and deep venous thrombosis prophylaxis can be administered as per institutional protocol.

Surgical Management

With fistulas due to obstetric injury, which occur in the immediate postpartum period, at least 3 months elapse before the acute inflammation subsides and fibrosis develops. In the interim, symptoms can be improved with stool-bulking agents or with induced mild constipation with loperamide or other antidiarrheals. Once inflammation subsides, a thorough evaluation of the sphincter mechanism should be undertaken to delineate the extent of sphincter disruption.

The presence of sepsis is an absolute contraindication to any attempt at surgical repair; thus drainage of abscesses and collections is the first step in management. A loose noncutting seton is usually placed through the fistula tract and kept in place until the infection subsides; this may take as long as 3 months and even longer in patients with Crohn's disease.

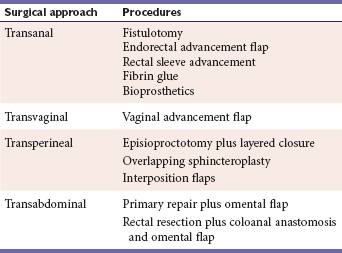

There are four surgical approaches to repair a rectovaginal fistula: transanal, transabdominal, transvaginal, and transperineal. Table 2 lists the various surgical options of each approach.

Transanal Approach

Fistulotomy

A fistulotomy involves laying open the fistula tract, which may or may not be excised. This is often performed as a two-stage procedure, in which a noncutting seton is first placed through the fistula to allow for drainage and fibrosis. In the second stage, the seton is removed by dividing the remaining tissue to lay open the tract.

Although a fistulotomy results in successful healing, it involves division of varying thicknesses of the external sphincter muscles. This causes a keyhole deformity, which almost always results in some degree of incontinence, often permanent. Hence a fistulotomy, although indicated only for superficial fistulas, is rarely used.

Endorectal Advancement Flap

Endorectal advancement flap forms the mainstay of treatment for low rectovaginal fistulas and is best suited for patients who do not have disruption of the sphincter muscles. The procedure is usually performed in the outpatient setting and with the patient in prone position, which offers excellent exposure of the anterior rectal wall. Both the anus and vagina are prepared, and a probe is inserted through the fistula from the vagina into the rectum. A trapezoid flap is then outlined with the base cephalad and twice the width of the apex. The flap consists of the rectal mucosa, submucosa, and a portion of the underlying internal sphincter, including the fistula opening at the apex; this is raised in cephalad manner with the use of needle-tip electrocautery. A sufficient length of flap should be mobilized 3 to 4 cm proximal to the fistula opening to ensure a tension-free closure after excision of the fistula. Injection of a dilute epinephrine solution facilitates dissection and minimizes blood loss.

After the flap is elevated, the fistula tract is curetted to remove all granulation tissue, and the defect in the remaining muscle layer (internal sphincter) is closed with a few interrupted absorbable sutures. The tip of the flap is then excised to remove the fistula opening, and the flap is advanced caudad and sutured in place with 3-0 interrupted absorbable sutures to close the wound. The vaginal opening is left open to facilitate drainage. Postoperative care includes a high-fiber diet, sitz baths, and stool softeners to avoid fecal impaction.

The endorectal advancement flap offers the advantages of performing the repair from the high-pressure side of the fistula and of preserving sphincter integrity. Short-term success rates for rectal advancement flaps alone vary from 42% to 68%, although higher success rates have been reported with the addition of a sphincteroplasty, if a sphincter defect exists.

Rectal Sleeve Advancement

In the presence of limited circumferential or stricturing disease in the distal rectum (e.g., Crohn's disease), a rectal sleeve advancement can be attempted. The procedure involves mobilization of the proximal rectum, resection of the involved distal portion, and restoration of continuity with an anorectal anastomosis.

Kraske Approach

The patient is placed in a semiprone jackknife position, and an incision is made just to the left of the midline, extending from the sacrococcygeal joint to the external anal sphincter. The incision is deepened, and the distal portion of the coccyx is excised. The pelvic floor muscles are then divided in the midline down to the rectum, which is circumferentially mobilized superiorly as far as possible and distally up to the anal canal. The rectum is then transected at the level of the pelvic floor. A circumferential mucosectomy is then performed from the level of the dentate line up to the level of rectal transection. The fistulous tract is completely excised, and the defect in the rectovaginal septum is closed with a few interrupted absorbable sutures. The vaginal defect may be left open for drainage. The mobilized rectum is then advanced to the dentate line and sutured in a single layer with interrupted sutures.

Fibrin Glue

Fibrin glue attempts to seal the fistula tract with a fibrin plug, which allows for ingrowth of fibrous tissue that permanently closes the fistula with minimal dissection and no sphincter disruption. However, experience with fibrin glue in rectovaginal fistulae has been very limited because of disappointing results. Extrusion of the fibrin plug as a result of the short length of the fistula tract is the predominant cause of failure.

Bioprosthetics

Two bioprosthetics have been used for rectovaginal fistulae: the bioprosthetic mesh (Surgisis ES; Cook Surgical, Bloomington, Ind) and the Rectovaginal Fistula Plug (RVP; Cook Surgical, Bloomington, Ind). Both products are made from lyophilized porcine intestinal submucosa, which provides a matrix for ingrowth of host connective tissue.

The bioprosthetic mesh is used as an interposition graft. The rectovaginal septum is dissected through a perineal incision, and the fistula is excised. After closure of the rectal and vaginal openings, the rehydrated mesh is placed between the rectum and vagina with an adequate overlap over the rectal and vaginal closures; it is sutured in position with a few interrupted absorbable sutures, with the mesh kept as taut as possible.

The bioprosthetic rectovaginal fistula plug is tapered at one end to facilitate insertion. A fistula probe is introduced from the vaginal to the rectal opening, and the tapered end of the plug is tied to the probe with a suture. The probe is then withdrawn, the plug is pulled with it, and the button is lodged at the broader end at the rectal opening. The excess plug at the rectal end is then excised, and the plug is sutured in position with absorbable sutures, which closes the rectal mucosa over the plug. The vaginal opening is left open, and the excess plug is trimmed at this level. The short length of the fistula tract poses the same problem with the plug as with fibrin glue, which makes the plug suitable only for rectovaginal fistulas that are well over 1 cm in length.

The experience with bioprosthetics as a whole in rectovaginal fistulas is very small. Success rates of fistula closure by interposition techniques have been reported to be from 66% to 86%.

Transvaginal Approach

Vaginal Advancement Flap

In a technique similar to the rectal advancement flap, a flap of vaginal mucosa is raised, and the fistula tract is excised. The rectal mucosa is closed separately, over which the defect in the rectovaginal septum is approximated with interrupted absorbable sutures. The apex of the flap is then trimmed to excise the fistula opening and is sutured into position to close the wound.

The primary advantage of a vaginal flap is the use of healthy, pliable, and well-vascularized vaginal tissue, even though the repair is on the low-pressure side of the fistula. A vaginal flap is easier to mobilize than a rectal flap, especially in the presence of anorectal stenosis. In a comparative analysis of 11 studies, no difference was found in the closure rates between a rectal and vaginal advancement flap in rectovaginal fistulas due to Crohn's disease.

Transperineal Approach

Episioproctotomy and Layered Closure

This repair converts the fistula into a fourth-degree perineal tear by dividing all the tissue between the rectum and vagina through the perineal body. A layered closure is then performed to close the rectal mucosa, the rectal and vaginal muscular walls, and finally the vaginal mucosa. The greatest disadvantage of this procedure is the creation of a full-thickness defect in the anal sphincter. If the repair should fail, the patient will be fully incontinent. For this reason, this procedure should be attempted in only patients with documented existing sphincter disruption and incontinence.

Overlapping Sphincteroplasty

This technique is ideal for patients with concomitant sphincter injury. The detailed technique of an overlapping sphincteroplasty is described elsewhere in this text but essentially involves dissection and mobilization of the external sphincter through a transperineal approach. Very often the sphincter is so attenuated at the site of injury that the healthy ends of the sphincter can be overlapped and sutured into position without the need to divide or excise any tissue. This technique has the advantage of not worsening the degree of incontinence should the repair fail while still achieving the same end result. In the presence of sphincter injury, the addition of an overlapping sphincteroplasty to a rectal advancement flap has been reported to greatly increase the success rates.

Interposition Flaps

Patients with multiple failed attempts at repair usually have relative ischemia in the surrounding tissues. The interposition of healthy, vascularized tissue in the rectovaginal septum can theoretically increase the chance of successful closure but with a potential risk of de novo dyspareunia. The gracilis and bulbocavernosus flaps are the two most described pedicled flaps for rectovaginal fistula. Although not mandatory, fecal diversion is usually recommended, either before or at the time of the flap procedure.

The approach is usually via a perineal incision between the posterior fourchette of the vagina and the anal verge. The incision is deepened to expose the rectovaginal septum, which is then dissected proximal to the level of the fistula by about 2 cm. The fistula is then completely excised, and the rectal and vaginal defects are closed primarily.

The gracilis muscle has only vestigial function, and a reliable vascular pedicle enters the muscle laterally in its upper third. The muscle of either leg can be used and is harvested through an incision in the medial aspect of the thigh. The harvested muscle is then tunneled through the subcutaneous tissue at the groin and brought out at the perineal incision. This is then placed between the rectum and vagina and held in position with a few interrupted absorbable sutures. The success rate of the gracilis muscle flap has been reported to be as high as 75%.

A Martius flap, in which the bulbocavernosus muscle is used with the overlying fat in the labia majora, is based on the perineal branch of the pudendal artery and is placed in the rectovaginal septum in similar fashion. As with all interposition flaps, this repair has the potential risk for increased postoperative dyspareunia, but there are usually no complaints related to labial function or cosmesis. The success rate with this procedure has been reported to vary from 50% to 93.8%.

Transabdominal Approach

Rectal Sleeve Advancement

The patient is placed in the lithotomy position, and the rectum is mobilized anteriorly and posteriorly in standard fashion, right down to the pelvic floor, and the lateral vascular supply is kept intact. The rectum is then transected at the pelvic floor, which completes the abdominal part of the procedure. The transanal exposure and anastomosis is as described in the Kraske approach.

A rectal sleeve advancement can be offered only if the proximal rectum is normal and is most appropriate in patients with limited, circumferential disease in the distal rectum. Closure rates of 54% to 87% have been described for a rectal sleeve advancement flap in studies with a follow-up greater than 2 years.

Omental Interposition

This transabdominal approach is best suited to repair high rectovaginal fistulas, which are usually a complication of anterior resection, hysterectomy, or diverticulitis. The rectum is dissected down to the level of the fistula, which is then divided to expose the rectal and vaginal openings. If the rectal wall is healthy and pliable, the fistula opening can be débrided and closed primarily. However, if the surrounding rectum is unhealthy, a resection with primary coloanal anastomosis may be considered. The vaginal opening is then closed, and a pedicled omental flap is placed between the two closures and held in position with a few interrupted sutures.

Sometimes, a low rectovaginal fistula may require a transabdominal approach. After the failure of multiple local procedures, further attempts at repair with manipulation of local tissues have a very slim chance of success. A transabdominal approach in this setting has the advantages of resecting all ischemic tissue and bringing down well-vascularized tissues to the anal canal.

The procedure entails mobilization of the rectum and separation of the rectovaginal septum down to the pelvic floor. The fistula openings in the rectum and vagina are then débrided and closed perineally with interrupted absorbable sutures. An omental flap, based on either the left or right gastroepiploic artery, is prepared and placed in the pelvis. From the perineum, the lower rectovaginal septum is dissected free. The omental flap is then brought down into the rectovaginal septum and sutured to the subcutaneous tissue of the perineum. Additional sutures are placed to anchor the omentum to the levator ani along the lateral pelvic walls for tension-free interposition (Figure 1). Although this is a major surgical procedure, it brings vascularized omentum into the rectovaginal septum between the rectal and vaginal closures and may be the only option for successful closure in patients with multiple failed procedures.

FIGURE 1 A, Probe delineating fistula. Dashed line indicates incision site. B, Posterior wall of vagina dissected from anterior rectal wall. Fistula sites débrided. Peritoneal cavity entered at apex of plane between vagina and rectum (dashed line). C, Fistula openings closed with interrupted polyglactin sutures. Mobilized omentum pulled down between vaginal and rectal repairs. D, Omentum sutured to subcutaneous tissue of perineum. Center of incision left open for drainage. E, Technique of omental mobilization based on left gastroepiploic artery as major blood supply. The dashed line represents the line of separation of greater omentum from the stomach. The arrows depict the downward rotation of the omentum for interposition. F, Lateral view showing completed interposition. (Courtesy Russell Pearl, MD.)

Treatment Guidelines

Fecal Diversion

There is no consensus on the indications of proximal fecal diversion in rectovaginal fistulas, as it has been shown that a stoma does not necessarily ensure the success of a repair. However, after two failed attempts, surgeons are more inclined to place a diverting stoma prior to or at the time the third procedure is attempted. Repairs using interposition pedicle flaps are also more likely to be protected with a proximal stoma.

Choice of Repair

Considering the diverse etiology, the large number of surgical options, and the lack of randomized evidence, deciding on a line of treatment is often a daunting task. The choice of procedure is largely governed by the type of fistula (low or high, simple or complex), the etiology, the status of the sphincter mechanism, the number of prior failed attempts, and the functional status of the patient.

The results reported for each procedure vary greatly, and no procedure yields consistent results. It should be appreciated that almost any procedure for rectovaginal fistula is going to fail in a significant number of patients. This is why irreversible steps, such as full-thickness sphincter division, which might make the condition worse if the repair fails, are best avoided.

Probably the first point to consider in deciding on a line of treatment is the status of the sphincter mechanism. Documented defects in the anal sphincter with associated incontinence require an overlapping sphincteroplasty. This procedure is often combined with a rectal advancement flap and is the most commonly used first-line option in low fistulas resulting from obstetric trauma.

In the absence of sphincter injury, either a rectal or vaginal advancement flap can be considered as first-line options. Although the results for both procedures are more or less similar, a rectal advancement flap puts the repair on the high-pressure (rectal) side of the fistula and is often preferred over the vaginal flap. However, a rectal flap necessitates the presence of a healthy rectum and is best avoided in the presence of poorly controlled Crohn's proctitis or in the presence of rectal disease involving strictures.

If a rectal flap fails as the first procedure, it would probably be better to try the vaginal flap at the second attempt rather than to repeat the rectal flap. After failure of both a rectal and vaginal flap, the surgeon has the option of repeating a flap procedure or of considering an interposition pedicle flap. If the local tissues are still healthy and pliable, a repeat flap can be attempted. However, it should be appreciated that at every subsequent procedure, the success rate decreases further. Multiple failed attempts (more than three) render the rectovaginal septum and surrounding tissue ischemic, and further attempts at local repair are less likely to succeed. Interposition flaps should then be considered with appropriate counseling in view of the potential for de novo dyspareunia. Either a gracilis or Martius flap is an acceptable alternative.

Because experience with bioprosthetics is limited, definitive recommendation for their use is impossible. However, because bioprosthetics rely on tissue ingrowth from surrounding tissue, an ischemic rectovaginal septum would probably not be the best environment for a bioprosthetic mesh. If the proximal rectum is healthy, a distal proctectomy with a coloanal anastomosis will resect the diseased distal rectum, bring healthy proximal rectum to the anal canal, and also provide the opportunity to place a pedicled omental flap in the ischemic rectovaginal septum.

Special Considerations

Radiation-Induced Fistulae

With the increased use of both brachytherapy and external-beam radiation in the treatment of pelvic malignancies, radiation-induced complications are likely to increase. The first step in management of radiation-induced rectovaginal fistulas is to rule out the presence of residual or recurrent malignancy. This requires detailed imaging and an examination with the patient under anesthesia with multiple biopsies of areas of irregularity or random biopsies if no irregularity exists. Once the presence of malignancy has been ruled out, the condition of the rectum, vagina, and surrounding perineal tissues needs to be evaluated.

It is mandatory to wait at least 6 months after the completion of radiation treatment before any repair is attempted. This allows for the full effect of radiation to be realized and for the surrounding tissue to recover. If the local tissues are healthy, a rectal or vaginal advancement flap can be attempted. However, it should be appreciated that because the repair is being performed with radiated tissue, it is less likely to succeed. If one attempt at local repair fails, subsequent attempts will most likely be futile. Interposition flaps with nonradiated tissue (e.g., gracilis flap) or a resection of the involved rectum with a coloanal anastomosis and omental interposition then remains the best available option and is preferable to the classic Bricker procedure.

Crohn's Disease

Almost every patient with Crohn's proctitis and a rectovaginal fistula will require an examination under anesthesia and drainage with a noncutting seton until the infection and inflammation subsides. This is also essential to optimize medical therapy. After quiescence of the acute episode, definitive therapy for the rectovaginal fistula can be pursued.

Local repair is the initial choice in most cases of Crohn's disease–associated rectovaginal fistulae. If the rectum is relatively free from disease, and the rectal wall is pliable, a rectal advancement flap can be attempted. However, in the presence of rectal scarring, this procedure is best avoided. The alternatives include an anocutaneous flap, rectal sleeve advancement, or vaginal flap. An anocutaneous flap can be done only if the anal skin is soft and supple, which is often not the case in patients with Crohn's disease, although a success rate of 70% has been reported for this procedure. The vaginal advancement flap is another alternative for which good healing rates have been reported, especially when a portion of the levator ani muscle is interposed between the rectal and vaginal walls below the flap of vaginal mucosa. Closure rates with this technique have been reported to be as high as 92.3%; however, a 40% to 60% success rate is probably more realistic in Crohn's disease.

Crohn's disease–associated rectovaginal fistulae have an overall poor prognosis, with a recurrence rate that varies from 25% to 50%. It is therefore very important to elaborately counsel patients and set realistic treatment goals. In patients with poorly controlled proctitis, surgical options are very limited. Quite often patients are symptomatic from the abscesses associated with the repeated flare-ups of Crohn's proctitis. Prolonged seton drainage for 12 to 18 months epithelializes the fistula tract and limits further episodes of abscess. Very often, patients with multiple failed procedures prefer prolonged seton drainage to a total proctocolectomy and permanent ileostomy, which is the procedure of last resort.

Malignancy

The only definitive treatment of malignant rectovaginal fistulae is an en block surgical extirpation of the fistulous tract with the mass and any contiguous organs involved in the malignant process. This often requires a posterior or total pelvic exenteration. A diverting stoma is often placed to decrease symptoms, while the patient receives neoadjuvant therapy. The patient should then be reevaluated after adjuvant treatment to determine the extent of response and fitness for a major surgical procedure. In patients of good performance status with a satisfactory response to adjuvant therapy, a pelvic exenteration may be considered. However, very few patients fit this description, and treatment remains palliative in most cases.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Russell Pearl, MD, for his contribution of the artwork for this chapter.

Ellis, CN. Outcomes after repair of rectovaginal fistulas using bioprosthetics. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008; 51(7):1084–1088.

Lefèvre, JH, Bretagnol, F, Maggiori, L, et al. Operative results and quality of life after gracilis muscle transposition for recurrent rectovaginal fistula. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009; 52(7):1290–1295.

Ruffolo, C, Scarpa, M, Bassi, N, et al. A systemic review on advancement flaps for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease: transrectal versus transvaginal approach. Colorectal Dis. 2010; 12(12):1183–1191.

Schouten, WR, Oom, DM. Rectal sleeve advancement for the treatment of persistent rectovaginal fistulas. Tech Coloproctol. 2009; 13:289–294.

Venkatesh, KS, Ramanujam, P. Surgical treatment of traumatic cloaca. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996; 39(7):811–816.