Male Breast Cancer

Overview

Carcinoma of the male breast is an exceptionally rare entity and accounts for less than 1% of all breast cancers and 0.1% of cancer mortality in men. The American Cancer Society estimates that in 2012, 2190 new cases of invasive breast cancer will be diagnosed in men and 410 men will die of breast cancer. Male breast cancer (MBC) warrants special consideration to foster prompt diagnosis and institution of appropriate therapies. Because of low clinical acuity and suspicion in men with breast symptoms, breast cancer tends to be diagnosed at later stages, with at least half of the cases presenting with stage 2 or higher breast cancer. It is not surprising then that approximately half of patients have regional spread of disease to the axillary lymph nodes at the time of diagnosis. Fortunately, the 5-year survival rates are similar across stages, comparable with women, although the overall survival rate in men tends to be lower than in women. This is thought to be largely because of the older age at diagnosis and resulting increased comorbidities.

Given the rarity of this disease, whether male breast cancer has its own distinct biology is difficult to ascertain. Treatment strategy for male breast cancer and determination of prognosis is extrapolated from our understanding of female breast cancer, with adjustments made for differences in anatomy and hormonal variations in men.

Risk Factors

Because of the rarity of this disease, establishment of causative links to development of MBC has been challenging. Similar to female breast cancer, the risk of MBC is increased twofold to threefold in patients with a positive family history of breast cancer and can be significantly higher in those with a known genetic predisposition. The most familiar gene mutation responsible for MBC is the BRCA 2 gene. However, many other genetic mutations and syndromes can predispose to MBC, including mutations in the AR gene, cytochrome p45017 (CYP17), PTEN tumor suppressor gene associated with Cowden syndrome, CHEK2 gene, and Klinefelter's syndrome (XXY karyotype).

Inherited MBC is most commonly associated with the BRCA 2 mutations, which account for approximately 40% of MBC. The lifetime risk of development of male breast cancer in a BRCA 2 carrier is approximately 7%, which is 80 to 100 times that of the normal population. BRCA 1 can also predispose to MBC, but at a much lower risk of approximately 1%, and can account for approximately 4% of MBC cases. Other risk factors for the development of MBC include alterations in the estrogen-testosterone ratio, history of radiation exposure, and some occupational hazards. It is speculated that men who are exposed to high-temperature environments may be predisposed to early testicular failure and that the resulting estrogen-testosterone imbalance may predispose to breast cancer.

Increased estrogen exposure or androgen insufficiency can predispose men to breast cancer. The most well-known associated syndrome with such a hormonal imbalance is Klinefelter's syndrome (XXY), which accounts for 3% of MBC cases. Males with this syndrome have testicular dysgenesis, gynecomastia, low testosterone levels, normal to low estrogen levels, and increased gonadotropin levels. This condition results in a high estrogen to androgen ratio, leading to a fiftyfold increased risk of development of breast cancer. Interestingly, this can be the outcome of abnormal hormonal stimulation resulting in proliferation of mammary duct epithelium or it may result from increased estrogen from the conversion of exogenous therapeutic testosterone in adipose tissue.

Men with undescended testes, congenital inguinal hernia, or orchitis or who have undergone orchiectomy are also at increased risk. Interestingly, obesity increases the estrogen-testosterone ratio and is considered a risk factor for MBC. Other considerations are increased estrogen levels in patients with cirrhosis with liver failure, in men treated for prostate cancer, and in transsexuals taking exogenous estrogens.

Presentation

Male breast tissue is predominately made up of ductal elements, stroma, adipose tissue, and subcutaneous fat. Lobular tissue, which in women is responsible for lactation, is usually absent in males unless they have increased estrogen exposure. Normal male breast anatomy lacks terminal lobules found in females; therefore, lobular carcinomas are rarely if ever encountered. Most male breast cancers are low-grade and intermediate-grade invasive ductal cancer; the remaining cases present with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS). Paget's disease and inflammatory breast cancer, rare entities in female patients, have been reported to occur in male patients as well. Most MBCs are hormone receptor positive and Her 2 neu negative, which translates into better prognosis if detected early.

Most men with breast cancer present at older ages compared with women with breast cancer, with the peak incidence occurring between ages 68 and 71 years, with a painless breast mass, localized to the subareolar area. It is sometimes difficult to discern this from changes associated with gynecomastia. However, gynecomastia tends to be bilateral and can be associated with tenderness. The tissue tends to remain soft and mobile as opposed to the firm lesions associated with malignancy. Of note, no definitive link between gynecomastia and MBC has been proven, and at present, gynecomastia is not considered a risk factor for the development of carcinoma. Other findings suggestive of breast cancer in females may be evident on examination, including regional lymphadenopathy, nipple retraction, or nipple discharge. Nipple discharge, if present in men, should alert the physician to a more ominous finding. Given the smaller amount of breast tissue in men, cancers can involve the local adjacent tissues, specifically the overlying skin and chest wall musculature.

Diagnosis

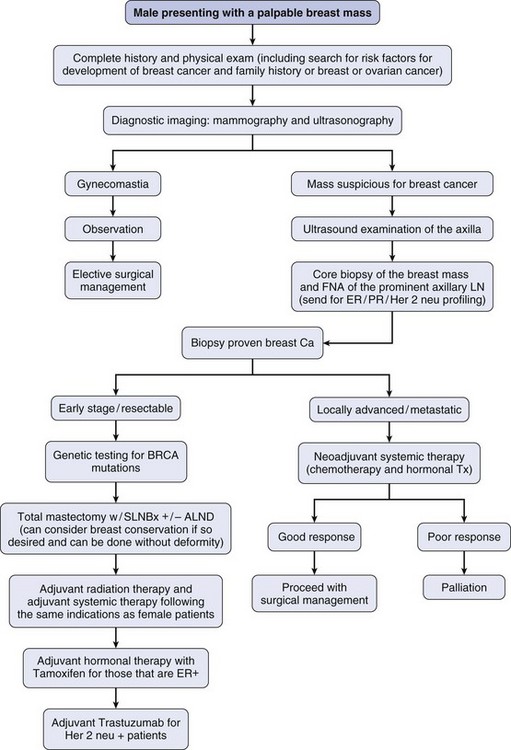

The evaluation of a palpable breast abnormality in a male should proceed in a similar manner as with female patients (Figure 1). A careful history and physical examination is conducted. Physical examination should include both breasts, the chest wall, and the regional nodal basins. This is followed by diagnostic imaging with mammography and ultrasound scan. Mammography has been shown to be 92% sensitive and 90% specific for detection of male breast cancer. Mammography remains the diagnostic tool of choice in men presenting with breast symptoms. Given the rarity of MBC, it is not justified as a screening modality except for those at particularly high risk, such as those with the BRCA 2 mutation. Ultrasound scan can help to better delineate palpable abnormalities, assess involvement of underlying musculature, and accurately assess regional nodal basins for nodal disease. It follows that any palpable lesion identified should be biopsied with image-guided core biopsy for confirmation of pathologic diagnosis and receptor status of malignant tumors. Patients with palpable lymphadenopathy or suspicious nodes identified on ultrasound scan should undergo fine-needle aspiration to determine management strategy. Evaluation of distant metastases follows the same strategy as for women and should be based on clinical assessment of symptoms suggestive of metastatic spread or in cases of locally advanced disease.

FIGURE 1 Treatment algorithm for a male with a palpable breast mass. ALND, axillary lymph node dissection; ER, estrogen receptor; FNA, fine needle aspiration; LN, lymph node; PR, progesterone receptor; SLNBX, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Of note, given the rarity of male breast cancer, a careful family history should be obtained and patients should be strongly considered for genetic counseling and testing. This test is performed to determine risk of development of additional cancers in the male patient, with heightened awareness of other cancer screenings that may be warranted, and also provides useful information to family members regarding their associated risk and possible preventative strategies. Male relatives discovered to have the BRCA mutation should be followed as high-risk cases and should closely adhere to strict surveillance programs with consideration of screening mammography for early detection. Given the rarity of MBC, little data exist regarding prophylactic surgery. However, it can be discussed with men who are BRCA 2 carriers for risk reduction in the same manner as female BRCA mutation carriers. Interestingly, males who have a family history of breast cancer and whose female relatives are proven to be BRCA+ are sometime not informed of these genetic test results. This is an important consideration in counseling female patients who undergo genetic testing.

Treatment

Although many surgical options are available for women diagnosed with breast cancer, the options available to men are more limited. If women are deemed candidates for breast conservation, they are often offered lumpectomy with sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNBX) followed by radiation; and those that require mastectomy can be offered skin-sparing mastectomy to facilitate reconstruction and nipple-sparing mastectomies that offer a pleasing cosmetic outcome. The anatomy of the male breast does not necessarily lend itself to breast conservation, with lesions that are typically located deep in the subareolar tissue, and the cosmetic outcome is improved with mastectomy. However, there is no specific contraindication to breast conservation in men if so desired and if it can be accomplished without disfigurement. Men do not undergo reconstructive procedures; therefore, skin-sparing and nipple-sparing mastectomies are not considered. Men diagnosed with breast cancer typically undergo total mastectomy. Axillary staging is an important component of surgical management, as studies have shown that men who underwent mastectomy without axillary dissection developed nodal recurrence and had poorer prognosis. Therefore, sentinel lymph node biopsy is appropriate in men and follows the same algorithm as used in female patients.

The decision for local radiation therapy follows the same guidelines as for women. This includes patients who present with large tumors, have microscopically positive margins that cannot be surgically improved, and who have four or more positive lymph nodes. Decision for systemic therapy is considered for the patients with advanced disease who are at risk of recurrence and death from breast cancer.

Given that most male breast cancers are hormonally sensitive, adjuvant hormonal manipulation is a crucial adjuvant therapy, with tamoxifen reducing the risk of recurrence. Similar to women, tamoxifen can lead to hormonal changes in men and is poorly tolerated by some. These changes include hot flashes, mood changes, and decreased libido and are present in approximately 20% of men. They are likewise at risk of venous thromboembolism. These side effects are in part responsible for the low compliance with hormonal therapy reported in male patients with breast cancer.

Patients with metastatic disease are managed in the same fashion as female patients. Given that most MBCs are estrogen receptor positive, hormonal therapy is often considered first-line therapy in the metastatic setting. Tamoxifen has established efficacy with a 50% response rate in metastatic male breast cancer. For males who are estrogen receptor negative who present with rapid progression of disease, chemotherapy can be considered for palliation. Trastuzumab should be considered in those that are Her 2 neu positive, extrapolating from evidence in female patients.

Prognosis

As with female breast cancer, staging follows the American Joint Committee on Cancer tumor node metastasis (TNM) staging system. Tumor size, grade of tumor, presence of lymph node metastases, and distant disease determine outcome. As in women, predictors of locoregional failure include positive margins, increased tumor size, and involvement of the axillary lymph nodes. Estrogen, progesterone status, and overexpression of Her 2 neu also help to predict prognosis and guide adjuvant therapies.

Even in those patients who do not have a genetic predisposition, those diagnosed with male breast cancer are at risk for subsequent cancers, which can include contralateral breast cancer, melanoma, and prostate cancer among others. Close follow-up for health maintenance is especially crucial for these patients.

The diagnosis, surgical treatment, and use of adjuvant therapies for patients diagnosed with male breast cancer remain largely extrapolated from our experience with female breast cancer patients; fortunately, this has been met with success. However, as MBC is increasingly recognized with treatment modifications accounting for differences in anatomy and hormonal balance, our knowledge regarding this disease will be broadened. This will advance our understanding of the disease and help to better determine optimal male specific treatment algorithms.

Johansen Taber, K, Morisy, L, Osbahr, A, et al. Male breast cancer: risk factors, diagnosis and management (review). Oncol Rep. 2010; 24:1115–1120.

Weiss, JR, Moysich, KB, Swede, H. Epidemiology of male breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005; 14:20–26.

White, J, Kearins, O, Dodwell, D, et al. Male breast carcinoma: increased awareness needed. Breast Cancer Res. 2011; 13:219–225.

Yamauchi, H, Woodward, W, Valero, V, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer: what we know and what we need to learn. Oncologist. 2012; 17:891–899.