Necrotizing Skin and Soft Tissue Infections

Overview

Necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections (NSTIs) represent a range of infectious conditions that cause deep tissue necrosis. NSTI is described by terms based on location of infection, pathogen, and depth of necrosis. The most frequently used terms are necrotizing fasciitis, Fournier's gangrene, clostridial myonecrosis, synergistic necrotizing cellulitis, and gas gangrene. Necrotizing fasciitis represents infection that extends through the deep fascia below the subcutaneous layers. Fournier's gangrene is a similar condition that originates in the perineum, whereas clostridial myonecrosis and synergistic necrotizing cellulitis extend into the deep muscle compartments and cause muscular necrosis. These diseases have received extensive media attention and have been lumped under the catchy rubric of “flesh-eating” bacterial disease. Hippocrates (500 bc) acknowledged necrotizing fasciitis as “diffuse erysipelas caused by trivial accidents, where flesh, sinews, and bones fell away in large quantities, leading to death in many cases.” The elaborate categorization of these conditions has caused confusion regarding this disease. Put simply, the pathophysiology of these infections in all categories is the same and is the result of bacterial penetration of skin defenses causing widespread necrosis and leading to rapid systemic deterioration and death. Any patient with signs or symptoms concerning for NSTI should raise a sense of urgency in the clinician for rapid diagnosis and early treatment. Unfortunately, the diagnosis of NSTI can be difficult and tempt the clinician to postpone life-saving treatment while obtaining time-consuming diagnostic studies. This should be absolutely avoided in favor of urgent operative management.

Pathophysiology

NSTI occurs when bacteria gain entry into the subcutaneous layers of the body where areas of relatively poor blood flow and relative hypoxia exist. Such conditions allow for poor immune response to infection and rapid overgrowth and spread of bacteria. Often, these microorganisms elaborate toxins that lead to both direct necrosis and indirect necrosis through thrombosis of perforating vessels and vasoconstriction increasing tissue hypoxia. Furthermore, these bacteria elaborate exotoxins that can lead to shock and multiorgan dysfunction.

Diagnosis

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare disease with an incidence rate estimated at 0.4 cases per 100,000 individuals by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control. Because delay in adequate treatment can have tremendous deleterious effects on outcome with increased morbidity and mortality, early diagnosis is paramount with necrotizing soft tissue infections. A thorough history and physical examination should be performed because this diagnosis relies more on clinical judgment rather than diagnostic testing. Certain comorbidities may predispose patients to this disease. Such conditions include advanced age, obesity, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, cirrhosis, chronic debilitation, vasculopathy, intravenous drug use, immunosuppression, malignancy, chemotherapy, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), congestive heart failure (conditions that impair oxygen delivery), end-stage renal disease, perirectal abscess, perforated viscus, and recent surgery. A thorough history for assessment of patient comorbidities and risk factors may help raise suspicion of this problem. Despite this extensive list of predisposing conditions, as many as 20% of NSTIs occur in patients with no apparent predisposing factor. Although NSTI may seem to occur spontaneously without any clear injury or portal of entry, NSTI often originates in the perineum, diabetic foot ulcers, decubitus ulcers, incision sites, and puncture and traumatic wounds and as a result of perforated viscus with subsequent seeding of soft tissues.

Initial physical examination findings may range from minimal to quite dramatic (Table 1). One may appreciate swelling, induration, mild to exquisite tenderness, mild to violaceous erythema, tenderness beyond areas of erythema, cutaneous anesthesia, necrotic tissue or skin with a blue or purplish hue, and wounds with exuding purulent, gray, or foul-smelling drainage (Figure 1). The skin may blister or slough, and crepitus may be present, indicating gas formation in the tissues. Crepitus, however, is present in only a fraction of patients and should not be relied on for diagnosis. One must keep in mind that obvious stigmata of NSTI may be subtle. Any patient with soft tissue pain out of proportion to examination findings should be considered to be potentially harboring an elusive deep NSTI that has yet to make itself obvious because early skin changes may be minimal despite extensive subcutaneous fat, fascia, or muscle destruction. Tenderness beyond areas of erythema may be particularly ominous because it is indicative of rapidly progressive infection in the deep layers beneath the skin.

TABLE 1:

Necrotizing fasciitis signs and symptoms

Wang YS, Wong CH, Tay YK: Staging of necrotizing fasciitis based on evolving cutaneous features, Int J Dermatol 46:1036-1041, 2007.

FIGURE 1 Black discoloration of penile, scrotal, and perineal skin in a patient with necrotizing infection of the perineum. Erythema, edema, and severe tenderness are also seen over the lower abdomen. (From Dolghi O, Itani KMF: Necrotizing infection of the perineum, Hosp Physician 44(1):39-45, 2008.)

The hallmark of NSTI is its rapidly virulent and destructive behavior. Tracking within the fascial planes beneath the skin, a place with poor vascularity and thus host defenses, allows for the rapid spread of bacteria and overwhelming infection. Most patients have quick development of signs of systemic toxicity, which include high fever, nausea, vomiting, malaise, tachycardia, hypotension, shock, mental status changes, and oliguric renal failure.

Laboratory values are nonspecific. White blood cell counts may reveal extreme leukocytosis, leukopenia, and high bandemia. Other common laboratory abnormalities include those that indicate dehydration/fluid sequestration, such as low bicarbonate levels, elevated blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and lactate levels. In addition, patients may present with hypoalbuminemia, elevated creatine phosphokinase, hyponatremia, and coagulopathy. The Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score system (Table 2) can be used as an adjunct for assessment of probability of necrotizing fasciitis. This should not, however, discourage operative débridement when clinical suspicion is high.

TABLE 2:

Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis (LRINEC) score system

| LRINEC Score | ||

| LRINEC variable | Value | Score points |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | <150 | 0 |

| >150 | 4 | |

| White blood cell count (cells/mm3) | <15 | 0 |

| 15-25 | 1 | |

| >25 | 2 | |

| Hemoglobin (g/dL) | >13.5 | 0 |

| 11-13.5 | 1 | |

| <11 | 2 | |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | ≥135 | 0 |

| <135 | 2 | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | ≤1.6 | 0 |

| >1.6 | 2 | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | ≤180 | 0 |

| >180 | 1 | |

| LRINEC Score | ||

| Points, sum | Risk category | Nectrotizing fasciitis probability |

| ≤5 | Low | <50% |

| 6-7 | Intermediate | 50%-75% |

| ≥8 | High | >75% |

For patients at intermediate and high risk, the model has positive predictive value of 92% and negative predictive value of 96%.

Wang YS, Wong CH, Tay YK: The LRINEC [Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis] score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections, Crit Care Med 32:1535-1541, 2004.

Because of the rapid lethality of necrotizing soft tissue infection, one should be cautious about obtaining advanced radiographic evidence of disease as this can delay lifesaving operative treatment. If obtained quickly in patients with relatively stable conditions, plain films may reveal air tracking in the soft tissues. Computed tomographic scan and magnetic resonance imaging may show air tracking in soft tissues, fascial separation, and abscess formation, but often these studies do not add much because they may only reveal nonspecific fat stranding. In patients with unstable conditions, these studies should be avoided in favor of rapid transfer to the operating room.

Biopsy of involved tissue typically reveals liquefaction necrosis of subcutaneous tissues and fascial layers with polymorphonuclear infiltrates and thrombosis of the perforating vessels to the skin. The fascial plains may weep a dishwater-appearing or hemorrhagic fluid.

Microbiology

Necrotizing fasciitis has recently earned a classification system based on the pathogen of origin. Type I represents polymicrobial infections, type II represents monomicrobial infections, type III represents marine organisms, and type IV represents fungal organisms. In all classifications, the organisms gain entry to the subcutaneous spaces, multiplying in areas of relative hypoxia and low blood flow and allowing for rapid proliferation.

As many as 75% of necrotizing soft tissue infections are polymicrobial, with an average of four organisms in a single infection (Table 3). For this reason, initial antibiotic treatment should be broad in spectrum. Polymicrobial infections often cause extensive local damage but on the whole are less lethal than other highly virulent monomicrobial infections. The most commonly isolated gram-positive organisms in polymicrobial infections include Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, and Enterococcus. Escherichia coli is the most common gram-negative organism isolated, whereas Bacteroides and Peptostreptococcus streptococcus are the most common anaerobes isolated from polymicrobial infections.

TABLE 3:

Organisms recovered from 198 consecutive patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections

| Organism | No. of cultures | No. of isolates (% of cultures) |

| Aerobic | ||

| Streptococci | 182 | 83 (45.6) |

| Enterococci | 182 | 61 (33.5) |

| Staphylococci | 182 | 64 (35.2) |

| Escherichia coli | 182 | 57 (31.3) |

| Proteus spp. | 182 | 38 (20.9) |

| Other gram-negative bacilli* | 182 | 76 (41.8) |

| Anaerobic | ||

| Peptostreptococci | 131 | 45 (34.4) |

| Bacteroides spp. | 128 | 70 (54.7) |

| Clostridium perfringens | 129 | 12 (9.3) |

| Other clostridia | 128 | 17 (13.3) |

| Other anaerobic species | 128 | 27 (21.1) |

| Fungal species | 171 | 9 (5.3) |

*In order of prevalence: Klebsiella spp., Enterobacter spp., Pseudomonas, Acinetobacter spp., Eikenella corrodens, Citrobacter feundii.

Elliott DC, Kufera JA, Myers RA: Necrotizing soft tissue infections: risk factors for mortality and strategies for management, Ann Surg 224:672-683, 1996.

The patient's history and physical examination may provide clues as to which organisms may be the culprit of the soft tissue infection. Soft tissue infections located in the perineum, those secondary to perforated viscus, and those secondary to decubitus ulcers or diabetic foot ulcerations tend to be polymicrobial in nature. These infections may contain all three, gram-positive, gram-negative, and anaerobic, organisms.

Bite wounds and water-borne infections are unique subdivisions of polymicrobial infections that, in addition to the more common bacteria species, tend to harbor unusual organisms, including Pasteurella multocida in cat and dog bites and Capnocytophaga carnimorsus from dog bites. In human bite wounds, Eikenella corrodens is common. Water-borne infections often contain Vibrio and Aeromonas species.

Monocrobial infections tend to be more aggressive, commonly presenting with acute onset and rapid progression to fulminant infection. Highly virulent pathogens include Streptococcus pyogenes (group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus), Clostridium species, community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), Vibrio vulnificus, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

Group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus, by far the most common monomicrobial isolate, can result in a rapidly progressive NSTI with systemic toxicity and high mortality rates. These bacteria produce exotoxins that independently cause systemic toxicity and result in multisystem organ failure. In addition, exotoxins released include powerful proteolytic enzymes such as hemolysins, fibrinolysins, hyaluronidases, antiphagocytic M proteins, leukocidins, and streptolysins O and S. These allow for rapid tracking through otherwise healthy tissue.

Clostridium species such as Clostridium perfringens are of particular concern in puncture and traumatic wounds and in intravenous drug users. Clostridium also produces exotoxins that are responsible for its rapid destructive spread, systemic toxicity, and high mortality. Clostridium reproduces every 8 minutes and produces α-toxin (phospholipase C) and θ-toxin (perfringolysin). These toxins cause direct tissue injury, kill neutrophils and impede migration, lead to hemolysis and microvascular thrombosis, and increase vascular permeability, which leads to rapid destruction of soft tissues including muscle tissue. In addition, α-toxin directly inhibits myocardial contractility, resulting in shock.

With the rise in MRSA in the community, the practitioner now sees NSTI as a result of MRSA infection. Community-acquired MRSA is able to produce coagulases that lead to direct tissue invasion and necrosis. In addition, these bacteria have the ability to produce Panton-Valentine leukocidin, which is a potent white blood cell and dermonecrotic toxin. Common populations affected with this disease include contact sports teams, prisoners, military recruits, injection drug users, institutionalized residents, and those who attend child and adult day care centers.

Treatment

Support

On identification of patients with necrotizing soft tissue infection, rapid operative management should be made the priority treatment and not be delayed for other therapeutic or monitoring measures. Nonetheless, supportive measures should be initiated as soon as possible, and these cases can be labor intensive from a supportive standpoint. Appropriate antibiotic therapy should be immediately delivered. Invasive monitoring should be implemented, including arterial lines for blood pressure monitoring and central venous lines for the delivery of medications and central venous pressure monitoring. Patients should receive aggressive fluid resuscitation and vasopressor and inotropic support when needed. Aggressive glycemic control can improve outcomes; thus, an insulin drip may be appropriate. Serial laboratory values should be obtained because these patients can have rapid fluid and electrolyte shifts. Foley catheter placement and lactic acid measurements can be used to direct fluid resuscitation. Urine myoglobin and creatine kinase levels should be obtained when myonecrosis is suspected. Blood products should be made available because development of coagulopathies or excessive operative blood loss is not unusual. Early parenteral or enteral support should be initiated on a patient-dependent basis. These patients exhibit high protein and caloric requirements because of their highly catabolic state.

Antibiotic Therapy

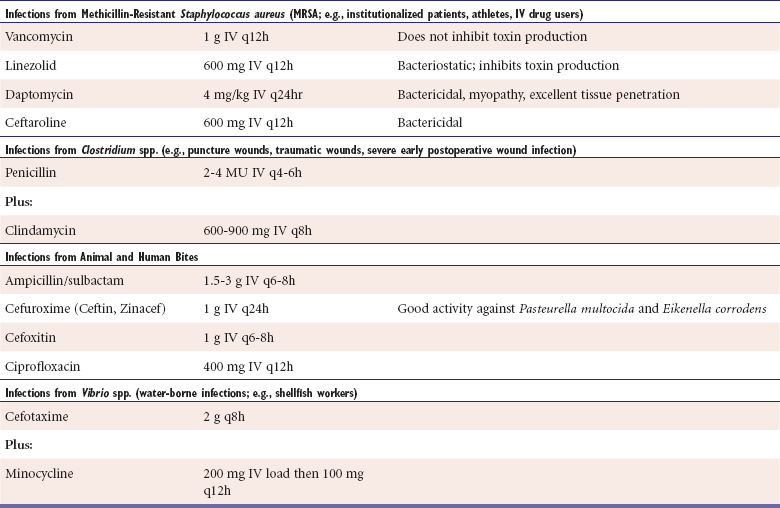

Antibiotic therapy should be initiated immediately on presentation and continued until no further evidence of infection in the involved tissues or sign of systemic toxicity is found. Antibiotic choice should initially be broad spectrum and then tailored to microbiology obtained from samples retrieved at the time of surgery (Table 4). One should acknowledge the likely origin of infection in choosing antibiotics. For example, infections from perineal and intraabdominal sources or from diabetic foot ulcers and pressure sores are more likely to be polymicrobial, whereas extremity infections are more likely to be monomicrobial. Extremity infections, infections related to intravenous drug use, and infections in patients from certain backgrounds, including prison inmates, Alaskan natives, institutionalized individual, and athletes, are more likely to harbor community-acquired MRSA.

TABLE 4:

Suggested empiric antimicrobial therapy for necrotizing infections based on suspected causative organism

Infections that are likely polymicrobial should be treated with broad-spectrum agents, such as imipenem-cilastin, meropenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, ticarcillin-clavulanate, and tigecycline. In patients with rapid spread or severe systemic toxicity, multiagent therapy should be considered. Streptococcal and Clostridial infections should generally be treated with high-dose penicillin and high-dose clindamycin. In addition to toxicity to said pathogens, evidence suggests clindamycin's ribosomal inhibitory properties may reduce toxin production responsible for widespread organ dysfunction, thus reducing toxicity. Infections at high risk for MRSA should be treated with antibiotic combinations including vancomycin or other anti-MRSA agent. Like clindamycin, linezolid also has ribosomal-blocking properties that may reduce toxin production.

A combination of penicillin and clindamycin with a gram-negative agent as empiric therapy provides several advantages, such as covering of a polymicrobial infection, the high prevalence of streptococcus in polymicrobial and monomicrobial infections, a better antibiotic tissue penetration, and the reduction in bacterial toxin production.

Surgery

Surgery should focus on rapid identification of affected tissue with complete excision of all devitalized skin and soft tissue (Figure 2). Reports show a sevenfold to ninefold increased risk of death with inadequate or delayed initial débridement. Incision should be made with dissection through all soft tissue layers until the deep muscle layers are encountered. A thorough probing of all tissue and fascial planes to assess for tracking should be made to direct further dissection. Typical findings that indicate devitalized tissue include murky dishwater-appearing fluid in the subcutaneous fat and fascial layers, tissue that dissects from deeper tissue with minimal resistance, nonbleeding tissue, and vascular thrombosis. Noncontractile muscle indicates devitalized muscle tissue. All tissue overlying involved fascial planes should be immediately débrided along with the affected fascia. Easy separation of fascia from underlying tissue with use of the “finger test” indicates active infection and indicates tissue that should be débrided. All fluid collections should be drained. Débridement should extend back to viable soft tissue and muscle that exhibit brisk bleeding. Tissue (including fascia) should be sent to microbiology for Gram stain and culture for aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal organisms to help tailor antibiotic usage.

FIGURE 2 Extensive débridement of the scrotum, penis, perineum, and lower abdomen was performed. A sigmoid loop colostomy was also created. (From Dolghi O, Itani KMF: Necrotizing infection of the perineum, Hosp Physician 44(1):39-45, 2008.)

In certain patient populations and NSTI presentations, operative management should be further tailored. Amputation may be necessary for infections that rapidly progress toward the trunk, involving major joints, or for extensive myonecrosis. Guillotine amputations of lower extremities should be considered, especially in patients with peripheral vascular disease for rapid containment of infection. In patients with Fournier's gangrene, all affected perineal soft tissue, including the scrotum and penile skin, should be débrided and colonic diversion considered. Colonic diversion may need to be delayed until a second operation depending on patient stability. Testicles can usually be preserved because they have an independent blood supply, although removal should not be delayed if they are involved. Patients with perforated viscus need the intraperitoneal injury to be addressed, likely with diversion if secondary to perforated colon.

Return to the operating room within 24 hours or earlier for a second look should strongly be considered, and débridement of any missed devitalized tissues performed. Patients may need multiple trips to the operating room before the infection is eradicated completely, with a median number of returns around four.

Wounds should be treated with serial wet-to-dry dressing changes until all infection has been cleared. Some authors prefer Dakin's solution–soaked or iodine-soaked gauze dressings, and some authors recommend the use of topical antibiotics, such as silver sulfadiazine. No tissue grafting should be attempted until the infection is fully treated and the patient's condition has stabilized.

Adjunct Treatments

Although urgent surgical débridement is the most important therapeutic maneuver for NSTI and should never be postponed in favor of other treatment modalities, it is worth mentioning a number of mostly theoretic adjunct treatments. These include hyperbaric oxygen therapy, intravenous immunoglobulin, and plasmapheresis. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy works on the premise that increased oxygen supply to infected tissues inhibits bacterial growth and improves host response to infection. Evidence supporting hyperbaric oxygen therapy is limited. Furthermore, because urgent surgical débridement is the most lifesaving therapy, no patient should be transferred to a facility housing a hyperbaric oxygen chamber without first undergoing adequate surgical débridement. Intravenous immunoglobulin works on the premise that the immunoglobulin binds exotoxins that cause systemic toxicity. Plasmapheresis works on the premise that it filters bacterial exotoxins that result in shock and multiorgan dysfunction. By reducing circulating toxin, intravenous immunoglobulin and plasmapheresis may hasten recovery from systemic shock. Again, evidence for these treatment modalities is controversial.

Reconstruction

Reconstruction should be initiated as soon as possible once all infection has been eradicated and systemic toxicity has subsided. This aids in restoring hemostasis, speeds healing, decreases fluid losses, and improves final cosmetic outcome. Split thickness skin grafts are favored. Staging reconstructions are used for complex reconstructions. The assistance of a plastic surgeon or urologist may be beneficial for difficult areas such as the hands, face, and perineum, particularly if flaps are needed or pockets need to be made for uncovered testicles.

Complications

Multiple complications can occur with NSTI. Despite attempts at improving recognition and speed to surgical management of necrotizing fasciitis, improvement in mortality has been plagued with death rates remaining around one in four. Obviously, with the extent of débridement necessary, disfigurement and disability are considerable. Contractures can occur in involved limbs. Secondary infections in the critically ill are common and include line infections, pneumonias, urinary tract infections, and secondary soft tissue infections. For those with Fournier's gangrene, impotence and decreased sperm count or motility are common. In addition, débridement of the perirectal muscles may result in fecal incontinence and the need for a permanent colostomy.

Conclusion

Necrotizing soft tissue infections should be promptly recognized to expedite surgical treatment and minimize morbidity, long-term disability, and death. Diagnosis can be difficult, and no firm diagnostic criteria exist. The clinician must recognize the clues and have a low threshold for surgically exploring areas of concern.

Dolghi, O, Itani, KMF. Necrotizing infection of the perineum. Hosp Physician. 2008; 44(1):39–45.

Elliott, DC, Kufera, JA, Myers, RA. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: risk factors for mortality and strategies for management. Ann Surg. 1996; 224:672–683.

Lancerotto, L, Tocco, I, Salmaso, R, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: classification, diagnosis, and management. J Trauma. 2012; 72(3):560–566.

May, A, Stafford, R, Bulger, E, et al. Treatment of complicated skin and soft tissue infections. Surg Infect. 2009; 10(5):467–499.

Roje, Z, Roje, Z, Matic, D, et al. Necrotizing fasciitis: literature review of contemporary strategies for diagnosing and management with three case reports: torso, abdominal wall, upper and lower limbs. World J Emerg Surg. 2011; 6(46):1–17.

Stevens, DL, Bisno, AL, Chambers, HF, et al. Practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft-tissue infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2005; 41:1373–1406.

Wang, YS, Wong, CH, Tay, YK. Staging of necrotizing fasciitis based on the evolving cutaneous features. Int J Dermatol. 2007; 46:1036–1041.

Wong, CH, Khin, LW, Heng, KS, et al. The LRINEC (laboratory risk indicator for necrotizing fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections. Crit Care Med. 2004; 32:1535–1541.