Injury to the Spleen

Overview

The spleen is the most commonly injured organ in blunt abdominal trauma. The management of splenic injury has fluctuated over the past century from observation and expectant management in the early twentieth century to primarily operative management for all injuries, and now to the current practice of selective nonoperative management (NOM). The shift in treatment is a result of our changing technology and understanding of the spleen's role in immunologic function.

The spleen's role in immunologic response was demonstrated in a publication by Morris and Bullock in 1919, revealing an increase in mortality in postsplenectomized rats challenged with Bacterium enteritidis compared to controls. The risk of postsplenectomy infection was not demonstrated in humans until 1952 in a landmark paper by King and Shumacker. In this case series, the authors described death due to sepsis in two of five infants who had undergone splenectomy for congenital hemolytic anemia. Subsequently, several authors noted this increased rate of overwhelming sepsis in adults. The reported rate of postsplenectomy overwhelming sepsis varies depending on the age at splenectomy and indications, with the highest risk in very young children and in patients undergoing splenectomy for hematologic disorders. Although the rate of sepsis after splenectomy is low, it is a lifelong risk for these patients. This knowledge led to an increased emphasis on splenic preservation.

Initially attempted in children, comfort grew with NOM of splenic injury in adults as computed tomography (CT) became more widely available and with the realization that negative laparotomies carry significant morbidity. As angioembolization techniques become more refined, it is increasingly used as an adjunct to NOM, with improvement in NOM success.

Diagnosis

The initial management of all trauma patients should follow the guidelines of the American College of Surgeons Advanced Trauma Life Support. Trauma patients often have multiple confounding injuries that make physical examination unreliable. Therefore, the diagnosis of splenic injury relies on a high index of suspicion. Factors that should increase the index of suspicion include hypotension, abdominal ecchymosis, abdominal pain or tenderness, presence of lower left rib fractures, and presence of pelvic fractures. It is important to point out that the presence of acute hemoperitoneum does not always lead to abdominal pain and tenderness, especially in the absence of clot lysis. Referred left shoulder pain (Kehr sign) is not reliably present, but even if present, it is often confounded by multiple injuries.

Diagnostic and management decisions in patients with blunt splenic injury rely heavily on the presence or absence of hemodynamic stability and the response to resuscitation. The initial evaluation and management of patients with blunt splenic injury is summarized in Figure 1. During the initial assessment, blood should be drawn for laboratory testing, including hemoglobin, electrolytes, markers of metabolic stress (base deficit or lactate), coagulation profile, and blood typing. Intravenous access should be obtained for resuscitation and potential intravenous contrast administration. A hypotensive, patient who does not respond to fluid resuscitation or who only transiently responds to fluid administration should undergo a focused assessment with sonography for trauma (FAST) examination. A positive FAST examination indicates presence of peritoneal fluid and, in the case of a trauma patient, hemoperitoneum until proven otherwise. An emergent laparotomy is indicated in these patients. For patients who are unstable and have a negative FAST examination, intra-abdominal hemorrhage is not reliably excluded. FAST may be repeated in 15 to 30 minutes or a diagnostic peritoneal aspirate (DPA) or lavage (DPL) should be considered as the next step to rule out intra-abdominal hemorrhage. Other alternative causes of hemorrhagic shock, such as thoracic injuries, pelvic injuries, external blood loss, or other types of shock, should be considered. For patients without a clear source of hemorrhage and who remain unstable despite resuscitation, immediate laparotomy should be considered.

FIGURE 1 Algorithm for management of blunt splenic injury. ATLS, Advanced trauma life support; CT, computerized tomography; DPA, diagnostic peritoneal aspiration; FAST, focused abdominal sonography for trauma. (Adapted from Moore FA, Davis JW, Moore EE, et al: Western Trauma Association (WTA) Critical decisions in trauma: management of adult blunt splenic trauma, J Trauma 65:1007-1011, 2008.)

The FAST examination evaluates three areas of the abdomen for the presence of intra-abdominal fluid: the hepatorenal fossa (Morrison's pouch), the splenorenal fossa, and the area around the bladder. A fourth view evaluates the pericardium for pericardial fluid. The presence of fluid in any of these locations indicates a positive examination. Like other sonographic studies, the accuracy of FAST is operator dependent and limited by the patient's body habitus and presence of subcutaneous emphysema. FAST only allows determination of the presence of fluid within the abdominal cavity. It does not provide the source of the fluid or evaluation of the retroperitoneum. The reported sensitivity of FAST varies. Generally, FAST has a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 96%; however, at some large trauma institutions, the sensitivity may be as low as 50%. The false negative rate for FAST is higher in the setting of pelvic trauma, thoracolumbar spine fracture, hematuria, and rib fractures.

When FAST is negative, the suspicion for intra-abdominal hemorrhage remains high, and the patient remains too unstable to be safely taken to the CT scanner, DPA may quickly provide an answer. It is the aspiration portion of the diagnostic peritoneal lavage without the lavage. When performed percutaneously, DPA is rapid and safe, and it does not have the high sensitivity of DPL. In a small prospective, observational trial, DPA had a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 100%.

For patients deemed hemodynamically stable, intravenous contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis is the study of choice for diagnosis of splenic injury. It allows for the grading of splenic injuries as developed by the American Association of the Surgery of Trauma (Table 1). When a single-phase CT scan identifies contrast extravasation outside the splenic parenchyma, it usually indicates active splenic hemorrhage, whereas a focal accumulation of contrast within the parenchyma is often a contained vascular injury. Contrast extravasation or “blush” has been used in the past to predict failure of NOM, guide selection for angioembolization, or even laparotomy. With the introduction of multidetector row CT systems in 1998, CT scanning is more rapid and has better spatial resolution, which has led to a greater sensitivity in detecting “blush.” However, with the greater sensitivity, it is not unusual to find no active bleeding on angiography in patients identified with a contrast “blush” on CT scan. Only 5% to 7% of all patients with blunt splenic injury have been found to have extravasation of contrast requiring angioembolization.

TABLE 1:

| Grade | Injury | Description |

| I | Hematoma | Subcapsular, >10% surface area |

| Laceration | Capsular tear, <1 cm parenchymal depth | |

| II | Hematoma | Subcapsular, 10% to 50% surface area, intraparenchymal, <5 cm in diameter |

| Laceration | 1-3 cm parenchymal depth that does not involve a trabecular vessel | |

| III | Hematoma | Subcapsular, >50% surface area or expanding; ruptured subcapsular or parenchymal hematoma |

| Laceration | >3 cm parenchymal depth or involving trabecular vessels | |

| IV | Laceration | Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels producing major devascularization (>25% of spleen) |

| V | Laceration | Completely shattered spleen |

| Vascular | Hilar vascular injury that devascularizes spleen |

Modified from Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Jurkovich GJ, et al: Organ injury scaling: spleen and liver (1994 revision), J Trauma 38:323-324, 1995.

Nonoperative Management

Selective nonoperative management is the standard of care for the hemodynamically stable patient with a blunt splenic injury in the absence of peritonitis. NOM should only be considered in environments that have the capability of monitoring and providing serial clinical exams and that have an operating room available for emergent laparotomy. Original exclusions for NOM in adults suggested that a high grade of injury, head trauma, quantity of hemoperitoneum, age greater than 55, contrast “blush,” and a large number of associated injuries precluded the ability to offer NOM. However, more recent literature has shown that the severity of splenic injury (by either grade or amount of hemoperitoneum), age greater than 55, neurologic injury, presence of contrast “blush,” and associated injuries should no longer be considered as absolute contraindications to NOM. Although found in only 0.3% of all blunt trauma admissions, hollow viscous injury as suggested by peritonitis, increasing abdominal pain, or suspicion for hollow viscous injury mandates exploration.

Angiography and embolization are controversial adjuncts to NOM. First described by Sclafani in 1996, embolization allows an improved splenic salvage rate, especially for grades III to V. Its success and acceptance are most likely tempered by the availability and skill of the interventionalist. Indications for angiography with embolization in blunt splenic trauma include contrast “blush” on CT with evidence of ongoing hemorrhage, pseudoaneurysm, AAST grades IV and V, moderate hemoperitoneum, or clinical evidence of continued hemorrhage. Multiple studies have shown improved success of NOM with its use. A NOM failure rate of 13% to 15% dropped to as low as 2% with embolization.

There is concern that the small increase in splenic salvage rate is not worth the 19% risk of major complications and 23% risk of minor complications reported in early studies. Major, potentially life-threatening complications include continued hemorrhage, total splenic infarction, splenic abscess, contrast-induced nephropathy, pancreatitis, and pneumonia. Minor, non–life-threatening complications include fever, pleural effusion, partial splenic infarction, pain, coil migration, and puncture site injuries. Bleeding is the most common complication and has been reported in 5% to 24% of those undergoing embolization. Minor complications such as fever are seen in over 50% of patients undergoing embolization. Centers where angiography and embolization for splenic injury are common often report low numbers of complications.

Controversy exists over embolization techniques. In experienced hands there is no difference in outcome when main splenic coil embolization is compared to distal or combined proximal and distal embolization. Although there is concern that embolization leads to splenic necrosis and negates the advantage of splenic salvage, recent studies have shown that splenic embolization does not impact immune function.

Roughly 85% of patients with blunt splenic injury are managed nonoperatively with over a 90% success rate. Patients with high-grade injury, large hemoperitoneum, vascular blush, pseudoaneurysm, and arteriovenous fistula are all at high risk of failure of NOM. Velmahos and colleagues found that of 40% of patients with grade IV splenic injuries treated nonoperatively, 65.5% were successful. Sixteen percent of patients with grade V injuries were treated nonoperatively, and 40% were successful. Of those patients who do fail, approximately 75% will fail within 48 hours of injury, 88% within 5 days, and 93% within 1 week of injury. In a review of a statewide discharge database, the 180-day risk of splenectomy following NOM and discharge home was 1.4%. Patients must be given specific discharge instructions about what symptoms may indicate a need for rapid return to the hospital.

Controversy continues to reign over the hospital management of a patient with blunt splenic injury treated nonoperatively. The frequency of serial hemoglobins, abdominal exams, and monitoring; determining when an oral diet should be started; deciding whether to use bed rest; determining the optimum length of stay in both the intensive care unit (ICU) and the hospital; determining the necessity of repeat imaging; and setting limitations on activities after discharge are all questions in which definitive data are lacking. As resources have become more limited, recent studies have attempted to address the optimal care of the patient with blunt splenic injury without sacrificing safety. A retrospective study found that early mobilization did not alter the risk of delayed hemorrhage and that bed rest was unnecessary. Recently published protocols suggest that grade I splenic injuries can be discharged as early as 1 to 2 days after injury if their hemoglobin is stable and vital signs remain normal. Grade II and higher injuries differ between published protocols. Most will discharge grade II injuries when the hemoglobin is stable and vital signs are normal. Grade III injuries and above are admitted to the ICU and had a minimum overall length of stay of at least 3 days. Figure 2 is a suggested management guideline for patients chosen for NOM. Each institution will need to modify this depending on its resources and patient population.

FIGURE 2 Suggested management guidelines for those patients chosen for nonoperative management (NOM). A “stable” hemoglobin is defined as a decline of 0.5 g or less.

D/C, Discharge; H/H, hemoglobin/hematocrit; LOS, length of stay; Abd, abdominal; NG, nasogastric tube; VS, vital signs. (Adapted from Cocanour CS: Blunt splenic injury, Curr Opin Crit Care 16:575-581, 2010.)

Repeat imaging in patients managed nonoperatively is controversial. Most repeat CT scans did not change patient management. An Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma survey found that only 14.5% of surveyed surgeons routinely obtain follow-up CT scans. Those physicians who routinely reimage splenic injuries with CT scans and angioembolize as indicated believe that their aggressive approach greatly contributes to their high NOM success rate. Currently, there is not enough evidence to recommend routine follow-up CT scans.

Clinical judgment is the predominant factor in determining a return to activity, including contact sports for patients with blunt splenic injuries treated nonoperatively. Restrictions may be recommended for less than 6 weeks for grades I and II injuries and longer than 6 months for grades IV and V injuries. The American Pediatric Surgical Association published management guidelines in 2000 for return to unrestricted activity that included “normal” age-appropriate activities that suggested 3 to 6 weeks for grades I to IV, respectively. Return to full-contact, competitive sports was left at the discretion of the pediatric surgeon.

Penetrating Splenic Injury

Penetrating abdominal injuries due to gunshot wounds are usually managed by laparotomy. Isolated stab wounds to the spleen may undergo a trial of NOM. However, splenic injuries from penetrating trauma are often accompanied by injuries to the bowel. Penetrating injuries to the spleen tend to violate intraparenchymal anatomic planes, and as a consequence, arterial injury and subsequent pseudoaneurysm formation are common. Because of the risk of delayed bleeding, splenectomy should be considered at the initial exploration. If it is an isolated splenic pole injury that can be treated by resection of the injured segment of the spleen, splenorrhaphy may be considered in the absence of accompanying bowel injury.

Operative Management

When it is determined that the patient with blunt splenic injury requires operative management, preparation for trauma laparotomy is essential. Blood is sent for crossmatch, and preoperative antibiotics are given. The patient should be placed in a supine position and is induced under general anesthesia. The patient's chest, abdomen, pelvis, and midthighs are prepped and sterilely draped. All measures to prevent hypothermia should be instituted, including using only warm intravenous (IV) fluids.

A midline incision is made that extends from the xyphoid to the pubic symphysis. Upon entering the abdomen, blood and clots are rapidly evacuated, and the abdomen is packed in all four quadrants to control hemorrhage. The priority should be given to hemorrhage control first followed by control of gastrointestinal contamination. The presence of clots in a particular quadrant should provide a clue as to where the source of hemorrhage may be. Active hemorrhage should first be controlled, and then the rest of the abdomen should be inspected systematically.

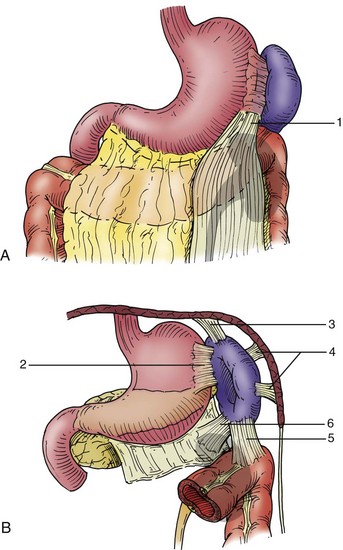

To adequately evaluate the injured spleen, it must be completely mobilized from all of its attachments and brought to the midline. Splenic attachments are shown in Figure 3. The left costal margin is retracted laterally and superiorly to facilitate exposure. The surgeon's hand is placed posterior to the spleen, and the spleen is rotated medially to expose the lienophrenic and lienorenal ligaments. By compressing the spleen against the spine medially with the surgeon's hand, bleeding from the spleen can be temporarily controlled. The lienophrenic and lienorenal ligaments are generally avascular and can be divided either with cautery or Metzenbaum scissors. Sometimes, these ligaments have to be divided by feel with scissors because exposure is not always adequate. The surgeon's index finger is inserted under the cut lienorenal ligament, and with a combination of blunt and sharp dissection, the spleen is freed from Gerota's capsule and the diaphragm. In the same plane, the surgeon's hand slides to the posterior surface of the tail of the pancreas, and both the spleen and the tail of the pancreas are elevated to the midline incision. It is helpful at this point to place a few laparotomy pads in the splenic fossa to help elevate the spleen. The lienocolic ligament is then divided, freeing the spleen from the omentum and colon. This ligament generally contains small vessels that require ligation. The short gastric vessels are then ligated and divided at this time, freeing the spleen from the stomach. Care should be taken during this step to ligate the short gastric vessels far from the stomach to prevent entrapment of the stomach wall. A nasogastric tube in the stomach can be used as traction, which helps expose the short gastric vessels for ligation.

FIGURE 3 Splenic attachments encountered when completely mobilizing the spleen. A, Lieno-omental peritoneal band (1). B, Lienogastric ligament (2), lienophrenic ligament (3), lateral perisplenic adhesions (4), lienocolic ligament (5), and lienorenal ligament (6). (Adapted from Cooper CS, Cohen MB, Donovan JF, Jr: Splenectomy complicating left nephrectomy, J Urol 155:30-36, 1996.)

At this point the spleen is mobile on its vascular pedicle and can be adequately inspected. If splenectomy is required, the splenic artery and vein are suture ligated close to the spleen to avoid injury to the tail of the pancreas. The splenic bed is then inspected to ensure hemostasis. Using a rolled-up laparotomy pad in the deepest part of the fossa and slowly rolling the pad anteriorly and medially allow systematic inspection of the fossa. The tail of the pancreas should be inspected for injury. If injury to the tail of the pancreas is suspected, a closed-suction drain should be placed near the tail of the pancreas. Routine use of drains after splenectomy is not recommended because it is associated with increased incidence of subphrenic abscess.

Most patients with splenic injuries are taken to the operating room for hemodynamic instability. Therefore, the most prudent operation is splenectomy. Splenic salvage should be considered only in hemodynamically stable patients who are not coagulopathic or hypothermic. Grades I and II injuries can be controlled with electrocautery, argon beam coagulation, and application of topical hemostatic agents. Sutures buttressed with omentum, Teflon, absorbable mesh, and oxidized regenerated cellulose (Surgicel; Ethicon, Inc., Somerville, NJ) have been described for higher-grade injuries. If simple hemostatic methods do not work, splenectomy should be considered. More aggressive approaches to splenorrhaphy could be considered in very young children who are hemodynamically stable.

Immunizations

The Surgical Infection Society guidelines recommend that patients undergoing splenectomy should receive pneumococcal vaccine and meningococcal vaccine, and for high-risk patients, Haemophilus influenza vaccine. The optimal time for vaccinations for patients undergoing splenectomy for trauma is 14 days postoperatively. However, due to concern for lack of follow-up, many institutions give vaccinations prior to discharge. Pneumococcal vaccination should be repeated 5 years after the first dose.

Cocanour, CS. Blunt splenic injury. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2010; 16:575–581.

Moore, FA, Davis, JW, Moore, EE, Jr., et al. Western Trauma Association (WTA) critical decisions in trauma: management of adult blunt splenic trauma. J Trauma. 2008; 65:1007–1011.

Stassen, NA, Bhullar, I, Cheng, JD, et al. Selective nonoperative management of blunt splenic injury: an Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma practice management guideline. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012; 73:S294–S300.

Stylianos and the APSA Trauma Committee. Evidence-based guidelines for resource utilization in children with isolated spleen or liver injury. J Pediatr Surg. 2000; 35:164–169.

Velmahos, GC, Zacharias, N, Emhoff, TA, et al. Management of the most severely injured spleen. Arch Surg. 2010; 2145:456–460.