Laparoscopic Inguinal Herniorrhaphy

Overview

Inguinal herniorrhaphy is the most common general surgery procedure performed, with 750,000 cases yearly in the United States. The lifetime risk of developing inguinal hernias is 27% in men and 3% in women, with direct annual costs at $2.5 billion. There are multiple contributing factors that lead to the development of inguinal hernias, including strain, collagen diseases, and hereditary factors. These stressors create a laxity of the muscles within the inguinal region, allowing progressive patency. Indirect hernias occur most commonly and result from the congenital invagination and eventual dilatation of a peritoneal sac running through the internal inguinal ring along the cord structures in men and round ligament in women. Direct hernias are the result of a weakened transversalis fascia lateral to the rectus muscles and above the inguinal ligament. Femoral hernias occur within the femoral canal medial to the femoral vein and are more commonly found in women with a high risk of incarceration.

The definitive treatment for inguinal hernias is surgery. The advantage of the laparoscopic approach is the ability to evaluate the entire myopectineal orifice and address all possible hernias originating from the inguinal region. The posterior approach of laparoscopic repair allows the lightweight mesh to be placed in an inlay fashion as opposed to the anterior onlay technique of open repair. There is a steeper learning curve for the laparoscopic approach compared to the open repair, as well as potentially longer operative times and higher costs. However, the benefits of the laparoscopic endeavor include less postoperative pain, shorter convalescence, and equivocal or lower recurrence rates compared to the open technique. However, complication rates for the laparoscopic approach may be higher than open until the surgeon performs up to 250 cases. Recurrence rates are lower than 6% and are commonly caused by incomplete reduction of the hernia sac, insufficient overlap of mesh over the defect, or missed small indirect hernias and cord lipomas. A common comment about laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy is higher cost compared to open. The LEVEL-Trial by Langeveld and colleagues comparing laparoscopic and Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair showed that operative costs were higher for the laparoscopic approach, mainly due to disposables and surgical equipment, but social costs were higher for the Lichtenstein approach due to more sick leave time needed. Overall, total costs were comparable between laparoscopic and Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair, making the laparoscopic approach a worthwhile investment from the patient and societal perspectives due to decreased postoperative pain and shorter convalescence, allowing earlier return to work.

Evaluating the Patient

Patients with symptomatic inguinal hernias are candidates for surgical repair unless they have comorbidities that outweigh their risk of strangulation. According to Fitzgibbons and colleagues, minimally symptomatic men should have the option of postponing surgery with minimal risk of acute incarceration, but they have a 23% chance of requiring surgical repair within 2 years, mostly due to pain.

The patient is asked about any pressure or bulging sensation over the inguinal site, which is commonly associated with activities that increase intraabdominal pressure such as lifting or straining. Any acute onset of severe inguinal pain associated with obstructive symptoms such as nausea or vomiting suggests bowel incarceration or strangulation, which may require acute surgical intervention. Patients should also have risk factors for complications addressed such as smoking, chronic cough, constipation, and obesity.

Physical examination includes assessing for the amount of tenderness to palpation, hernia size, reducibility, and for a contralateral defect. The external inguinal ring is palpated by invaginating the scrotum with the index finger toward the pubic tubercle while the patient is standing. A defect descending into the scrotum is likely an indirect hernia, while a bulge at the external inguinal ring is a direct hernia. Femoral hernias are most commonly found in women and can be palpated below the inguinal ligament medial to the femoral vessels. Patients are asked to perform a valsalva maneuver such as coughing to palpate the impulse of a small defect and to evaluate for a subtle contralateral hernia. Griffin and colleagues found that up to 22% of patients with unilateral inguinal hernias may have an occult contralateral defect not detected on physical exam. Therefore, most patients are consented for laparoscopic evaluation for bilateral inguinal hernias.

Relevant Anatomy

The preperitoneum is the space between the peritoneum and the bilaminar transversalis fascia. Both the totally extraperitoneal (TEP) and transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) procedures require entering this space. The anterior layer of the trasversalis fascia is attached to the rectus abdominus muscle, while the posterior transversalis fascial layer envelopes the cord structures and the bladder. Dissection of the peritoneal hernia sac off the cord structures should not disrupt the translucent posterior transversalis fascial layer to minimize dissection injury and potential mesh irritation to the cord structures. The retropubic space of Retzius lies anterior to the bladder between the medial umbilical ligaments. The space of Bogros extends laterally from the space of Retzius toward the anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS). These spaces need to be developed to allow adequate room for repair of the inguinal hernia and mesh placement.

The pubic symphysis is the cartilaginous joint between the superior pubic rami and denotes the midline. Cooper's ligament, also known as the pectineal ligament, is a lateral extension of the lacunar ligament and forms the periosteum of the superior pubic rami.

The oval-shaped myopectineal orifice of Fruchaud is the origin of all inguinal hernias. It is bound medially by the edge of the rectus muscle, laterally by the iliopsoas muscle, superiorly by the arch of the transversus abdominus and internal oblique muscles, and inferiorly by Cooper's ligament. The iliopubic tract is a thickened fold of transversalis fascia that extends from the pubic ramus to the ASIS and divides the myopectineal orifice into a superior and inferior portion. Below this tract is the femoral canal medially and external iliac vessels laterally. The Triangle of Doom contains the external iliac artery and vein, and it is bordered medially by the ductus deferens and laterally by the spermatic vessels (Figure 1). The Triangle of Pain contains the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve, the femoral branch of the genitofemoral nerve, and the anterior branch of the femoral nerve. It is bound medially by the spermatic vessels and superolaterally by the iliopubic tract. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve is most commonly injured and results in pain or numbness in the lateral upper portion of the thigh.

Hesselbach's triangle is bordered superolaterally by the inferior epigastric vessels, medially by the rectus muscles, and inferiorly by Cooper's ligament from the laparoscopic posterior perspective. Direct hernias protrude through Hesselbach's triangle medial to the inferior epigastric vessels, while indirect hernias enter the internal inguinal ring lateral to the epigastric vessels (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2 Hesselbach's triangle. (Illustration from Cameron JL, Sandone C: Atlas of gastrointestinal surgery, ed 2, vol II (in press); used with permission from PMPH-USA, Shelton, CT.)

The inferior epigastric vessels arise from the external iliac vessels and ascend medially toward the rectus muscle between the two layers of the transversalis fascia. In 20% of patients, a large pubic branch of the inferior epigastric artery courses inferiorly across Cooper's ligament and anastomoses to the obturator artery. This aberrant vessel is called the Corona Mortis, and it can potentially be injured while dissecting areolar tissue laterally on Cooper's ligament toward the femoral canal, leading to brisk bleeding. There is also a network of veins within the lower subinguinal Space of Bogros branching from the exterial iliac, coursing underneath Cooper's ligament and along the lower lateral fibers of the rectus muscles and iliopubic tract that may be injured with dissection. Collectively, this variable deep venous circle is called the circulation of Bendavid and is composed of the suprapubic, retropubic, deep inferior epigastric, and rectusial veins (see Figure 2).

Indications and Contraindications

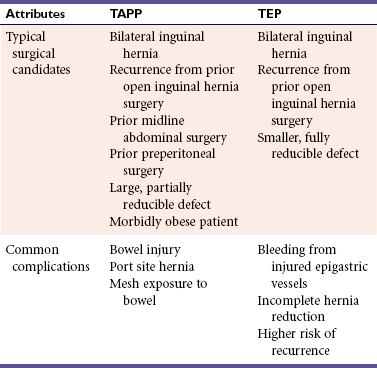

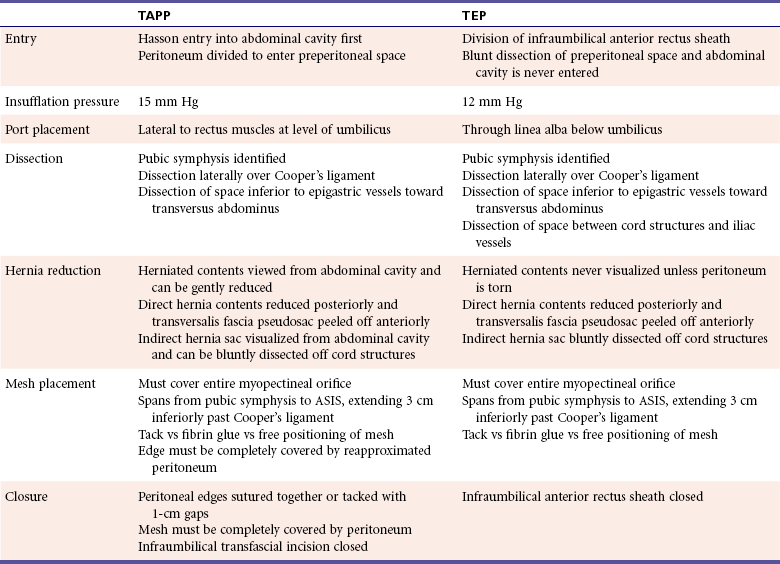

The laparoscopic approach is ideal for patients who are obese, have recurrence from a prior open approach, have bilateral hernias, or require an operation that may result in a shorter convalescence (Table 1). All laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs require placing mesh in the preperitoneal space to reinforce the myopectineal orifice. This was initially performed with a TAPP approach requiring initial entry into the abdominal cavity followed by division of the peritoneum and subsequent entry into the preperitoneal space. TAPP is preferred for patients with a large hernia or a prior infraumbilical abdominal incision because the contents of a large hernia can be assessed and reduced from the abdominal cavity, and scar tissue from a prior midline incision makes TEP entry more difficult due to adhesions. However, TAPP requires a transfascial incision into the abdominal cavity, which can lead to port site hernias and intestinal injury. TAPP also requires the divided peritoneum to be reattached to cover the mesh, which adds time to the operation. To address these issues, the TEP approach enters the preperitoneal space directly by staying above the posterior rectus sheath and peritoneal layer and never entering the abdominal cavity. TEP has a longer learning curve than TAPP due to a more limited operative field. However, TEP is associated with shorter operative time, fewer bowel injuries, and port site hernias, making it the preferred approach.

Absolute contraindications include severe illness, coagulopathy, and active severe infection. Acutely incarcerated hernias have a higher risk of bowel injury with laparoscopic manipulation and should undergo open repair. Although there are reports of laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy being performed with spinal anesthesia, patients who cannot tolerate general anesthesia should undergo open repair. Relative contraindications include prior surgery in the retropubic space, sliding hernias, large chronic incarcerated hernias, and ascites.

Preparing the Patient

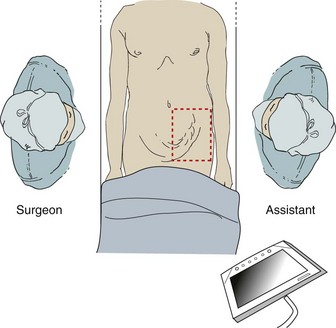

The patient is placed supine with video monitors at the feet, and bilateral sequential compression devices are placed on the lower extremities (Figure 3). The effectiveness of antibiotic prophylaxis is not clear. A randomized, double-blind study by Perez and colleagues looking at tension-free herniorrhaphy of 360 patients did not show a marked decrease in infections in the patient population receiving antibiotics.

After general endotracheal anesthesia is performed, the patient is positioned supine with both arms firmly tucked to the patient's side. A Foley is not placed to minimize the risk of postoperative urinary retention and urinary tract infections unless the patient has had prior inguinal or pelvic surgery. The patient is placed in mild Trendelenburg, and the hernia is manually reduced as much as possible.

The hair on the abdomen and groin are clipped, and the area is widely prepped with a chlorhexidine/isopropyl alcohol solution. The operative field is draped to allow for a TAPP, TEP, or open procedure using an iodophor adhesive sterile drape to keep the synthetic mesh from contacting skin.

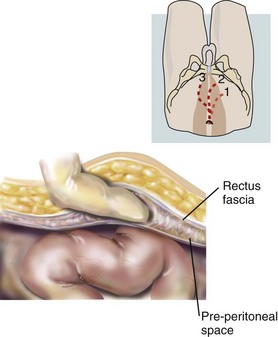

Totally Extraperitoneal

The surgeon stands on the contralateral side of the inguinal hernia. A 1-cm incision is made below the umbilicus, and blunt dissection continues past the thick orange Scarpa's fascia to the fibrous linea alba running between the rectus muscles (Figure 4). The linea alba is pulled up, and a 1-cm horizontal incision is made slightly laterally from the linea alba through the anterior rectus sheath extending toward the side with the hernia. The linea alba at midline is adherent to the peritoneum, so a deep incision will create a fascial defect communicating into the abdominal cavity. If this occurs, the defect is closed and the contralateral side can be incised to reattempt a preperitoneal approach, or a TAPP can be performed. The medial edge of the rectus muscle is visualized, and the fascial incision should be large enough to allow a finger to sweep behind the rectus muscle above the firm posterior rectus sheath (Figure 5). The rectus muscle is retracted laterally to visualize the white posterior rectus sheath. At this point, either the laparoscope or a dissecting balloon is used to bluntly dissect the preperitoneal space of Retzius. The use of the laparoscope as a blunt dissecting instrument begins with placing the scope below the rectus muscle and advancing toward the bony pubic symphysis while staying in the areolar space. Once below the arcuate ligament, the thick posterior rectus sheath is replaced by thin peritoneum. Blunt dissection is performed by moving the scope laterally within the preperitoneal plane to create enough space between the inferior epigastric vessels to allow 5-mm trocars to be placed.

FIGURE 4 A, First maneuver in dissection of an indirect hernia sac. B, Second maneuver in dissection of an indirect hernia sac. (Courtesy Anne Erickson, CMI.)

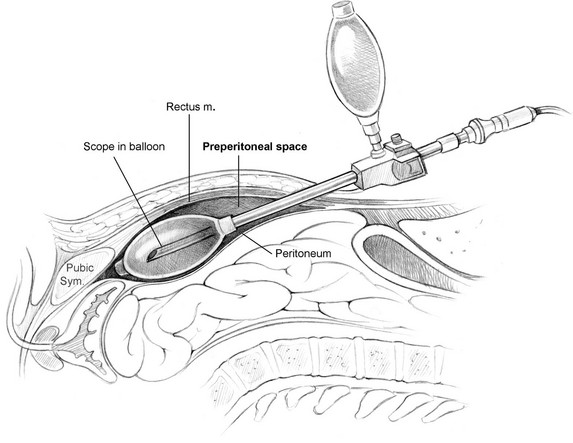

The dissecting balloon can create a similar space in the preperitoneal plane (Figure 6). The balloon is placed below the rectus muscles and directed inferiorly toward the pubic symphysis. The dissecting balloon needs to be advanced with minimal effort, or either the balloon was placed too anteriorly or the incision was too small to accommodate the device. After the tip of the balloon touches the pubic symphysis, a 10-mm angled laparoscope is placed into the lumen of the balloon as it is inflated. Visualization of bowel or omentum means that the peritoneum is torn and the balloon is now in the abdominal cavity. If this happens, the operation can proceed as a TAPP or be converted to an open approach. Next, the inferior epigastric vessels should be seen anteriorly. Use of a dissecting balloon is associated with a higher incidence of vessel injury due to dissection between the inferior epigastric vessels and the rectus muscles. If the balloon was placed too anteriorly, insufflation should stop, and the balloon is repositioned more posteriorly to the epigastric vessels. These vessels may be subtle to visualize in obese patients and are best found by looking toward the internal inguinal ring and finding a purple-white stripe that can be traced superiorly. The balloon is insufflated until a portion of the white edge of Cooper's ligament is seen. If there is minor bleeding from the dissection, the balloon is kept inflated to allow tamponade of the bleeding. Afterward, the scope and dissecting balloon are removed from this preperitoneal space and a 10-mm trocar is placed with insufflation set at 12 mm Hg to minimize subcutaneous emphysema.

FIGURE 6 Dissecting balloon. (Illustration from Cameron JL, Sandone C: Atlas of gastrointestinal surgery, ed 2, vol II [in press]; used with permission from PMPH-USA, Shelton, CT.)

The 5-mm trocars are placed inferiorly to the umbilicus through the linea alba, where space has been created to minimize the risk of tearing the peritoneum. The first 5-mm trocar is placed three fingerbreadths above the pubic symphysis to allow adequate space for mesh placement, and the second trocar is placed at the midpoint between the pubic symphysis and the umbilicus. The patient can be placed in further Trendelenburg to optimize visualization.

Dissection begins by palpating the bony pubic symphysis. The areolar space is bluntly separated to reveal Cooper's ligament as dissection continues laterally toward the femoral canal, looking for the aberrant Corona Mortis. Injury of this vessel can be prevented with gentle blunt dissection of the lateral portion of Cooper's ligament. If injury occurs, the Corona Mortis is grasped quickly to prevent posterior retraction and further bleeding, followed by clipping. Brisk bleeding can quickly obscure the injured vessel, which lies very close to the external iliac vein.

Dissection continues laterally by next identifying the inferior epigastric vessels and bluntly dissecting through the areolar tissue posterior to these vessels, with the intention of creating space toward the transversus abdominus arch and ASIS laterally. After the muscle striations of the transversus abdominus are seen laterally, dissection is continued superiorly past the ASIS to allow adequate space for mesh placement. In creating this space, the anterior-superior portion of the cord structure has been identified.

A direct hernia is encountered medially to the inferior epigastric vessels and is reduced by retracting the herniated contents posteriorly until the white edge of the weakened transversalis fascia is seen. The edge of this pseudosac is circumferentially peeled anteriorly as the herniated fatty tissue continues to be pulled posteriorly and reduced completely. The lateral edge of the defect can involve portions of the inferior epigastric vessel. If the direct defect is large, the redundant transversalis fascia can then be pulled into the preperitoneal space and tacked above Cooper's ligament medially to minimize seroma formation.

The cord structure needs to be separated from the iliac vessels to allow adequate space for the safe reduction of the indirect hernia sac. This is done most easily adjacent to the internal inguinal ring, which is identified by following the epigastric vessels inferiorly to the external iliacs. The internal inguinal ring and cord structure is directly lateral to the inferior epigastrics at this point. The cord structure spreads out in a triangular configuration proximally, with the ductus deferens being the medial border of the triangle. Loose fatty tissue overlying the cord is bluntly swept off. Once seen, the ductus is pushed anteriorly and laterally with the rest of the cord structure as gentle blunt dissection allows further separation between the cord structures and iliac vessels. The indirect sac is the thin blue-white peritoneum attached to the cord structure. Dissection adjacent to the internal inguinal ring allows identification and separation of the sac from the cord structures. The sac is often densely adherent to the cord structure and requires steady retraction to separate it from the cord structures. Blunt dissection is used to sweep the adherent tissue off the medial and lateral sides of the sac as the edge is isolated and peeled off the cord structure (Figure 7). Branches of the delicate pampiniform plexus may be adherent to the hernia sac and should be carefully handled to minimize the risk of venous thrombosis leading to testicular ischemia. Once separation between the sac and the cord structure is established, steady retraction and separation of the sac from the cord structure will allow it to be pulled out of the internal inguinal ring until the tip of the distal edge comes into view. The tip of the sac is peeled back to the psoas muscle, allowing mesh placement that will completely exclude the sac. If tearing of the sac occurs, a vessel loop or clipping is used to close the peritoneum to prevent bowel exposure to mesh and to minimize insufflation of the abdominal cavity. If necessary, veress decompression can be performed in the left upper abdominal quadrant. If the sac is large and cannot be completely separated from the cord structure, then a high ligation can be performed. After complete division, the distal sac can be seen retracting into the inguinal canal, and the proximal sac is closed with a vessel loop.

Often a large cord lipoma is identified running lateral to the cord structures into the internal inguinal ring. These lipomas can create a sizeable bulge that is clinically relevant to the patient and must be reduced from the inguinal ring. The fatty composition of the cord lipoma is slightly different from the cord fatty tissue, and the larger fat globules can be easily reduced from the inguinal canal with steady pressure, making sure that there are no vessels encased in the lipoma. Similar to a hernia sac, the cord lipoma is bluntly separated from the cord structures and reduced back from the internal inguinal ring to allow complete exclusion after the mesh is placed.

If clinically indicated, femoral hernias can be reduced by first identifying the external iliac vessels by tracing the inferior epigastrics caudally. After clearing the fatty tissue medial to the iliac vessels, the femoral canal is found below the iliopubic tract and above Cooper's ligament. The hernia is reduced with circumferential blunt dissection. Lymphatics in the areolar tissue and large adjacent vessels require dissection directly over the hernia sac to minimize injury. If the hernia is too densely adherent or incarcerated, the operation should be converted to open to minimize catastrophic injury to the external iliac vessels.

Intraoperative evaluation of an occult contralateral hernia does not require additional skin incisions and should take less than 15 additional minutes to perform. Easy detection and repair of a contralateral hernia is a known advantage of the minimally invasive approach and saves the patient from a subsequent operation through a larger open incision or through scarred preperitoneal tissue.

After evaluation for a contralateral hernia, the operative field should have ample space from the pubic symphysis to the ASIS bilaterally. A lightweight 10 × 15-cm mesh can adequately cover and reinforce the myopectineal orifice on each side. The corners of the mesh are trimmed to allow ease of placement. Creating a slit in the mesh to allow the cord structures to pass may increase the risk of reherniation or chronic pain and is not done. There is commercially available mesh with a preformed notch to allow placement over the cord structures. The mesh is inserted through the 10-mm trocar and should lie flat, with the medial edge at midline over the pubic symphysis and the lateral edge at the palpable ASIS. The inferior edge of the mesh should extend 3 to 4 cm past Cooper's ligament inferiorly, leaving adequate mesh to cover the potential direct, indirect and femoral defects (Figure 8).

There is a growing body of evidence, such as studies by Messaris and colleagues, that show that hernia repair without mesh fixation does not lead to early recurrence. Furthermore, fibrin glue has also gained popularity as a way to fixate mesh with lower risk of complications from tacking such as inguinodynia. In performing a study evaluation comparing stapling versus fibrin glue fixation, we found that fibrin glue fixation achieves similar recurrence rates compared to staple fixation, but with a decreased incidence of chronic inguinal pain, and may be the preferred fixation technique. If tacking is to be performed, care must be taken to minimize risk of bleeding and bladder and nerve injury. Typically, the mesh is tacked above Cooper's ligament and rectus abdominus medially, avoiding the circulation of Bendavid. The mesh is never tacked below the bony ligaments to prevent injury to the bladder. Laterally, the ASIS is palpated externally with the nondominant hand to ensure the mesh is tacked into the transversus abdominus muscle above the iliopubic tract to minimize injury to the nerves within the Triangle of Pain. A contralateral hernia is fixed similarly with a separate piece of mesh that should slightly overlap at midline.

Afterward, the operative field is evaluated for bleeding or peritoneal tears. At completion, the 5-mm trocars are removed under direct vision to check for port site bleeding. All trocars are then removed, and the preperitoneum is allowed to desufflate. Any persistent abdominal tympany means that the abdominal cavity was inadvertently insufflated due to a peritoneal tear. A Veress needle can be used to decompress the abdominal insufflation. The anterior rectus sheath incision is then closed with 0-gauge absorbable suture. Local anesthesia is injected, and the skin is reapproximated. The scrotum is checked for swelling caused by insufflation as well as a retracted testicle.

Transabdominal Preperitoneal

Patient position and prepping is the same as TEP. The first incision is infraumbilical, and the abdominal cavity is entered with a Hasson technique and insufflated to 15 mm Hg. After initial laparoscopic evaluation of the abdominal cavity for overt pathology, two 5-mm trocars are then placed, each laterally from the umbilicus at the edge of the rectus muscle (see Figure 4). The patient is placed in further Trendelenberg, and the inferior epigastric vessels are followed caudally toward the external iliacs to identify the internal inguinal ring laterally and Cooper's ligament medially. A deep peritoneal indentation lateral to the inferior epigastrics at this point suggests the presence of an indirect hernia, while a broad indentation medial to the inferior epigastrics suggests a direct hernia. A punctate indentation medial to the external iliac vessels is consistent with a femoral hernia. Herniated tissue through the defect is carefully reduced as adhesions to the pelvic peritoneum are sharply divided. The peritoneum is divided using cauterization starting laterally at the palpable ASIS and continues in an upward arc formation medially with 3 to 4 cm distance from the edge of the hernia past the medial umbilical ligament. The peritoneum is pulled away from the epigastric vessels to minimize risk of injury. The medial umbilical ligament may have a patent umbilical vessel and is clipped and divided to allow adequate access to the preperitoneal space. Once in the preperitoneal plane, blunt dissection proceeds in a manner similar to the TEP technique and continues inferiorly through the alveolar tissue toward the pubic symphysis (Figure 9). Cooper's ligament is then cleared of areolar tissue, extending toward the femoral canal.

FIGURE 9 Transabdominal Ppreperitoneal (TAPP). (Illustration from Cameron JL, Sandone C: Atlas of gastrointestinal surgery, ed 2, vol II [in press]; used with permission from PMPH-USA, Shelton, CT.)

Dissection continues laterally toward the transversus abdominus muscle between the inferior epigastric vessels and the cord structures, which are then followed into the internal inguinal ring. The entire myopectineal orifice should be visible. A direct hernia is reduced by peeling the transversalis fascia anteriorly and reducing the herniated fatty tissue back into the preperitoneal space. The transversalis fascia of a large pseudosac can then be tacked to the rectus muscle to minimize postoperative seroma formation. From within the abdominal cavity, the peritoneum of indirect hernia sac can be separated from the cord structures. The ductus deferens and adherent testicular vessels are bluntly separated from the sac, which can be completely reduced back to the psoas. Once separated from the cord structures, the sac can also be ligated if the distal tip is too firmly adherent and cannot be reduced from the inguinal canal. A femoral hernia is bluntly separated from the external iliac vessels and gently reduced. A 10 × 15-cm lightweight mesh is placed transversely in the preperitoneal space to completely reinforce the myopectineal orifice from the ASIS to the pubic symphysis, extending 3 cm inferiorly past Cooper's ligament. The edge of the mesh is cut and tucked anteriorly to the peritoneum, and the divided peritoneal edge is reapproximated to completely cover the mesh. The peritoneum can either be sutured or tacked back together with gaps less than 1 cm to prevent bowel herniation into the gaps (Figure 10). Tacks are placed flush with the abdominal wall along the edge of the divided peritoneum. A reduced hernia sac may allow the redundant peritoneum to be more mobile and allow overlap of the edges. Peritoneal tears away from the edge should be closed with vessel loops and not tacked to prevent potential injury of critical preperitoneal structures. Often the omentum can be pulled down to further insulate the operative field from the bowel. After evaluation of the contralateral side for an occult hernia, a final evaluation for bowel injury is performed. The trocars are then removed under direct vision to look for bleeding, and the abdominal cavity is desufflated. The infraumbilical fascial defect is closed with 0-gauge absorbable suture, followed by local anesthesia and skin incision closure. The scrotum and testicles are then checked for swelling and retraction, respectively.

Management of Complicated Hernia

Reoperations for recurrent hernias comprise up to 17% of inguinal hernia repairs. They are typically performed laparoscopically if the prior attempt was an open approach to allow dissection within a plane with minimal scarring. Studies such as the ones by Kouhia and colleagues find that laparoscopic repair of recurrent inguinal hernia is superior to open mesh repair in several important clinical aspects, including less incidence of chronic pain and earlier return to work. Both TEP and TAPP approaches are acceptable methods with lower rerecurrence rates as compared to a reattempted repair with an open approach. The presence of prior mesh may cause the hernia sac to be more adherent and difficult to completely reduce and may require high ligation.

With large pantaloon hernias the direct and indirect defects may make dissection difficult in the TEP procedure. A TAPP approach allows more space for evaluation and reduction of the herniated contents and the hernia sac. A large direct component of the pantaloon hernia can sometimes obscure the inferior epigastric vessels. Therefore, it is reduced first to allow space for reduction of the indirect defect. A large patulous internal inguinal ring may be encountered, and the reduction of a cord lipoma first will allow easier identification and reduction of the indirect hernia sac. For large chronic hernias, high ligation may be necessary.

Incarcerated hernias are difficult to repair laparoscopically. The best approach is TAPP, where the herniated contents are visualized and potentially reduced. Placing the patient in steep Trendelenburg and applying taxis to the hernia may aid with reduction of herniated contents back into the abdominal cavity. Herniated omentum can be grasped and reduced with steady pressure, but laparoscopic reduction of incarcerated bowel can easily lead to injury, and the bowel must be inspected carefully.

Inguinal hernias are commonly found concomitantly in patients undergoing prostatectomies. Concerns regarding infection are raised with implantation of prosthetic mesh adjacent to newly formed bladder-urethral anastomosis. However, mesh infections have been shown to be low in studies such as the one published by Allaf and colleagues, prompting more patients to undergo simultaneous laparoscopic prostatectomy and inguinal herniorrhaphies with acceptable outcomes.

Laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery after prior preperitoneal surgery can lead to a higher rate of bleeding and bladder injury. The dissection balloon of the TEP approach may cause excessive bleeding, so the TAPP approach is used because it allows controlled dissection into the adherent preperitoneal plane. If it is safe to proceed, then blunt dissection is used to find the landmarks discussed above. Mild oozing can be temporized with pressure from the endo-kuttners, and bipolar electrocauterization is judiciously used in the severely adhesed plane. The bladder can be adherent above Cooper's ligament, and a Foley catheter is used to minimize the risk of bladder injury.

After Surgery

Patients are typically discharged the same day of surgery if they have minimal discomfort, are able to ambulate, and can adequately urinate. Once discharged, patients are encouraged to remain active. Over-the-counter analgesics and compresses prior to prescription medications are encouraged for pain control. A weight restriction of 15 pounds for 1 to 2 weeks is imposed, and patients can return to their normal activities after 2 to 3 weeks. Patients follow up 2 weeks postsurgery.

Complications

Postoperative urinary retention is treated with catheterization. Wound infections are aggressively treated to minimize the risk of mesh infections. Seromas can occur after repair of a large direct hernia and can be clinically differentiated from hernia recurrence by palpation. Typically a recurrent hernia can be partially reduced, while a seroma is a nonreducible, firm, fluid-filled sac that causes minimal discomfort for the patient. Seromas can take 3 to 6 months to completely resolve, and aspiration is seldom required unless the patient is severely symptomatic. If necessary, aspiration is performed with sterile technique to minimize the risk of mesh infection.

According to Ferzli and colleagues, postoperative chronic inguinodynia can range from 9.7% to 34%, and occurs more commonly in obese patients and those with significant preoperative pain (Table 2). Mild postoperative discomfort can be explained by nerve irritation from extensive dissections and should be transient. Antiinflammatory treatment and compresses should provide relief. Severe immediate postoperative pain of the inguinal region is usually due to nerve entrapment by a lateral tack. Use of fibrin glue or positioning of the tacker above the ASIS should minimize nerve injury, but a small percentage of patients have aberrant nerves found above the iliopubic tract that can potentially be injured despite appropriate technique. These patients are taken back to the operating room, and the lateral tacks are removed. Although the risk of testicular infarction is low with laparoscopic inguinal hernia, patients presenting 2 to 3 days after surgery with severe testicular pain and swelling should undergo Doppler sonography to evaluate the testicular blood flow.

Bowel injury should lead to conversion to open, at which time the bowel is thoroughly assessed and repaired. In the setting of contamination, synthetic mesh should not be used due to the high risk of mesh infection. The inguinal hernia can then be repaired with either a biologic mesh or a nonmesh technique such as a Bassini or a McVay procedure. The long-term efficacy with the use of biologic mesh for inguinal herniorrhaphy is not known.

Bleeding from injury to the inferior epigastric vessels can be controlled in many ways, including clipping, ligation with a suture-passer, or use of a 5-mm energy ligation device. The epigastric vessels are fed caudally from the external iliacs, so controlling the caudal side first will slow the bleeding more substantially. Injury to the iliac vessels requires immediate action after recognition. The site of injury to the iliac vessel needs to be grasped, and pressure is held to minimize the bleeding as the case is converted to open. This is done expeditiously because iliac vein injury has the additional risk of air embolism.

Summary

The laparoscopic inguinal herniorrhaphy can be performed safely and with good outcomes. Advantages include smaller wounds, shorter convalescence, and the ability to assess both sides. Earlier in the learning curve, surgeons should be comfortable with TAPP prior to attempting TEP and have a low threshold for conversion to open. Most of the operation can be performed with blunt dissection (Table 3).

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank the following people for their help with this chapter: Mike Rosen, Bruce Ramshaw, Michael Schweitzer, Thomas Magnuson, Mark Duncan, Fatima Khambaty, Jenny Hong, Josh Grimm, and James Harris.

Eklund, A, Montgomery, A, Bergkvist, L, et al. Swedish Multicentre Trial of Inguinal Hernia Repair by Laparoscopy (SMIL) study group: chronic pain 5 years after randomized comparison of laparoscopic and Lichtenstein inguinal hernia repair. Br J Surg. 2010; 97(4):600–608.

Matthews, RD, Neumayer, L. Inguinal hernia in the 21st century: an evidence-based review. Curr Probl Surg. 2008; 45(4):261–312.

Rosenberger, R, Loeweneck, H, Meyer, G, The cutaneous nerves encountered during laparoscopic repair of inguinal: new anatomical findings for the surgeon. Surg Endosc. 2000;8:731–735.

Shah, NR, Mikami, DJ, Cook, C, et al. A comparison of outcomes between open and laparoscopic surgical repair of recurrent inguinal hernias. Surg Endosc. 2011; 25(7):2330–2337.