The Illogic of American Racial Categories

I wrote this essay in 1991 at the request of Maria Root, as a theoretical introduction to her landmark edited book, Racially Mixed People in America (1992).1 She asked me to explain the constructed nature of race and ethnicity. The reader may perceive that I was feeling my way to an initial framing of these issues. I called on a scientist, James King, for authority on biological ideas about race and on Alice Brues for expertise from physical anthropology, although I gave their ideas a historical framing of my own. This essay attracted a ready audience; indeed, it has been reprinted several times without my permission, once by the PBS website.2 I choose to view that appropriation (they did at least list me as the author) as praise for the clarity with which I communicated fundamental ideas about race. This was my first attempt to sort out the way that race works conceptually and to provide a constructivist interpretation that has room for the possibility of multiraciality. I have left the argument and nearly all the prose as they were in the original. I have changed a few sentences for clarity and updated some of the numbers and references.

Ashamed of my race?

And of what race am I?

I am many in one.

Thru my veins there flows the blood

Of Red Man, Black Man, Briton, Celt and Scot

In warring clash and tumultuous riot.

I welcome all,

But love the blood of the kindly race

That swarthes my skin, crinkles my hair

And puts sweet music into my soul.

—Joseph Cotter, 1918

This poem by Joseph Cotter,3 a promising African American poet who died young early in the last century, highlights several of the ways Americans think about race. What is a race? And, if we can figure that out, what is a person of mixed race? These are central questions of this essay and this book.

In most people’s minds, as apparently in Cotter’s, race is a fundamental organizing principle of human affairs. Everyone has a race, and only one. The races are biologically and characterologically separate one from another, and they are at least potentially in conflict with one another. Race has something to do with blood (today we might say genes or DNA), and something to do with skin color, and something to do with the geographic origins of one’s ancestors. According to this way of thinking, people with more than one racial ancestry have a problem, one that can be resolved only by choosing a single racial identity.

It is my contention in this essay, however, that race, while it has some relationship to biology, is not mainly a biological matter. Race is primarily a sociopolitical construct. The sorting of people into this race or that in the modern era has generally been done by powerful groups for the purposes of maintaining and extending their own power. Not only is race something different from what many people have believed it to be, but people of mixed race are not what many people have assumed them to be. As the other essays in this volume amply demonstrate, people with more than one racial ancestry do not necessarily have a problem. And, in contrast to Cotter’s earlier opinion, these days people of mixed parentage are often choosing for themselves something other than a single racial identity.

RACE AS A BIOLOGICAL CATEGORY

In the thinking of most Europeans and Americans (and these ideas have spread around the world in the last century), humankind can be divided into four or five discrete races. This is an extension of the admittedly artificial system of classification of all living things first constructed by the Swedish botanist and taxonomist Carolus Linnaeus in the eighteenth century. According to the Linnaean system, human beings are all members of the kingdom Animalia, the phylum Chordata, the class Mammalia, the order Primates, the family Hominidae, the genus Homo, and the species Homo sapiens. Each level of this pyramid contains subdivisions of the level above. In the century after Linnaeus, pseudoscientific racists such as Johann Friedrich Blumenbach and Joseph Arthur, comte de Gobineau, tried to extend the system down one more level to human races, on the basis of geography and observed physical differences.4 Details of the versions differed, but most systems of categorization divided humankind into at least Red, Yellow, Black, and White: Native Americans, Asians, Africans, and Europeans. Whether Australian Aborigines, Bushmen, and various brown-skinned peoples—Polynesians and Malays, for example—constituted separate races depended on who was doing the categorizing.

There has been considerable argument, in the nineteenth century and since, over the nature of these “races.” The most common view has been to see races as distinct types. That is, there were supposed to have been at some time in the past four or five utterly distinct and pure races, with physical features, gene pools, and character qualities that diverged entirely one from another. Over millennia there had been some mixing at the margins, but the observer could still distinguish a Caucasian type (light of skin, blue-eyed, and possessing fine, sandy hair, a high-bridged nose, thin lips, etc.), a Negroid type (dark brown of skin, brown-eyed, with tightly curled black hair, a broad flat nose, thick lips, etc.), an Asian type, and so on. There was debate as to whether these varieties of human beings all proceeded from the same first humans or whether there was a separate genesis for each race. The latter view tended to regard the races as virtual separate species, as far apart as house cats and cougars; the former saw them as more like breeds of dogs—spaniels, collies, and so forth. The typological view of races developed by Europeans arranged the peoples of the world hierarchically, with Caucasians at the top, Asians next, then Native Americans, and Africans at the bottom—in terms of both physical abilities and moral qualities.5

Successors in this tradition further divided the races into subunits, each again supposed to carry its own distinctive physical, genotypical, and moral characteristics. Madison Grant divided the Caucasian race into five subunits: the Nordic race, the Alpine race, the Mediterranean race, the extinct races of the Upper Paleolithic period (such as Cro-Magnon humans), and the extinct races of the Middle Paleolithic period (including Neanderthal humans).6 Each of the modern Caucasian subunits, according to Grant, contained at least five further subdivisions. Each of the major subunits bore a distinctive typical stature, skin color, eye color, hair color, hair texture, facial shape, nose type, and cephalic index.7 Each was also supposed to carry distinctive intellectual and moral qualities, with the Nordic being the highest type. According to Henry Fairfield Osborn, even where there was achievement of distinction in non-Nordic peoples, it came from a previous infusion of Nordic genes. He contended in a New York Times article that Raphael, Cervantes, Leonardo, Galileo, Titian, Botticelli, Petrarch, Columbus, Richelieu, Lafayette, Joffre, Clemenceau, Racine, Napoleon, Garibaldi, and dozens of other Continentals were all actually of Nordic origin—hence their genius.8 In similar fashion, pseudoscientific racists saw White bloodlines as the source of the evident capabilities of Booker T. Washington, Frederick Douglass, and George Washington Carver.9

Over the course of the twentieth century, an increasing number of scientists took exception to the notion of races as types. James C. King, a prominent American geneticist on racial matters, denounced the typological view as “make-believe.”10 By the second half of the twentieth century, biologists and physical anthropologists were more likely to see races as subspecies. That is, they recognized the essential commonality of all humans and saw races as geographically and biologically diverging populations. Thus the physical anthropologist Alice Brues saw a race as “a division of a species which differs from other divisions by the frequency with which certain hereditary traits appear among its members.”11 They saw all human populations, in all times and places, as mixed populations. There never were any “pure” races. Nonetheless, there are populations in geographic localities that can be distinguished from each other by statistically significant frequencies of various genetic or physical traits, from blood type to hair color to susceptibility to sickle-cell anemia. Most such thinkers agreed, however, that the idea of race is founded in biology. Nineteenth-century Europeans and Americans spoke of blood as the agent of the transmission of racial characteristics. Throughout most of the second half of the twentieth century, genes were accorded the same role once assigned to blood. Nowadays, we speak of DNA.

The most important thing about races was the boundaries between them. If races were pure (or had once been) and if one were a member of the race at the top, then it was essential to maintain the boundaries that defined one’s superiority, to keep people from the lower categories from slipping surreptitiously upward. Hence US law took pains to define just who was in which racial category. Most of the boundary drawing came on the border between White and Black. The boundaries were drawn on the basis, not of biology—genotype and phenotype—but of descent. For purposes of the laws of nine southern and border states in the early part of the twentieth century, a “Negro” was defined as someone with a single Negro great-grandparent; in three other southern states, a Negro great-great-grandparent would suffice. That is, a person with fifteen White ancestors four generations back and a single Black ancestor at the same remove was reckoned a Negro in the eyes of the law.12

But what was a “Negro”? It turned out that, for the purposes of the court, a Negro ancestor was simply any person who was socially regarded as a Negro. That person might have been the descendant of several Caucasians along with only a single African. Thus, far less than one-sixteenth actual African ancestry was required in order for an individual to be regarded as an African American. In practice—both legal and customary—anyone with any known African ancestry was deemed an African American, while only those without any trace of known African ancestry were called Whites. This was known as the “one-drop rule”: one drop of Black blood made one an African American. In fact, of course, it was not about blood—or biology—at all. People with no discernible African genotype or phenotype were regarded as Black on the basis of the fact that they had grandfathers or other remote relatives who were socially regarded as Black, and they had no choice in the matter. The boundaries were drawn in this manner to maintain an absolute wall surrounding White dominance.

This leads one to the conclusion that race is primarily about culture and social structure, not biology. As the geneticist King admitted:

Both what constitutes a race and how one recognizes a racial difference are culturally determined. Whether two individuals regard themselves as of the same or of different races depends not on the degree of similarity of their genetic material but on whether history, tradition, and personal training and experiences have brought them to regard themselves as belonging to the same group or to different groups…. [T]here are no objective boundaries to set off one subspecies from another.13

The process of racial labeling starts with geography, culture, and family ties and runs through economics and politics to biology, not the other way around. That is, a group is defined by an observer according to its location, its cultural practices, or its social connectedness (and their subsequent economic, social, and political implications). Then, on looking at physical markers or genetic makeup, the observer may find that this group shares certain items with greater frequency than do other populations that are also socially defined. But even in such cases, there is tremendous overlap between racial categories with regard to biological features. As King wrote, “Genetic variability within populations is greater than the variability between them.”14

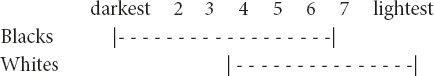

Take the case of skin color. Suppose people can all be arranged according to the color of their skin along a continuum:

darkest 2 3 4 5 6 7 lightest

The people Americans call Black would nearly all fall on the darker end of the continuum, while the people we call White would nearly all fall on the lighter end:

On the average, the White and Black populations are distinct from each other in skin color. But a very large number of individuals who are classified as White have darker skin color than some people classified as Black, and vice versa. The so-called races are not biological categories at all; rather, they are primarily social divisions that rely only partly on physical markers such as skin color to identify group membership.

Sometimes, skin color and social definitions run counter to one another. Take the case of Walter White and Poppy Cannon.15 In the 1930s and 1940s, White was one of the most prominent African American citizens in the United States. An author and activist, he served for twenty years as the executive secretary of the NAACP. Physically, White was short, slim, blond, and blue-eyed. On the street he would not have been taken for an African American by anyone who did not know his identity. But he had been raised in the South in a family of very light-skinned Blacks, and he was socially defined as Black, both by others and by himself. He dedicated his life and career to serving Black Americans. In 1949, White divorced his light-skinned African American wife of many years’ standing and married Cannon, a White journalist and businesswoman. Although Cannon was a White woman socially and ancestrally, her hair, eyes, and skin were several shades darker than her new husband’s. If a person were shown pictures of the couple and told that one partner was White and the other Black, without doubt that person would have selected Cannon as the Afro-American. Yet, immediately on White’s divorce, there was an eruption of protest in the Black press. White was accused of having sold out his race for a piece of White flesh and Cannon of having seduced one of Black America’s most beloved leaders. White segregationists took the occasion to crow that this was what Black advocates of civil rights really wanted: access to White women. All the acrimony and confusion took place because Walter White was socially Black and Poppy Cannon was socially White; biology—at least physical appearance—had nothing to do with it.

All of this is not to argue that there is no biological aspect to race, only that biology is not fundamental. The origins of race are sociocultural and political, and the main ways that race is used are sociocultural and political. Race can be used for good as well as for ill. For example, one may use the socially defined category “Black” to target for study and treatment a population with a greater likelihood of suffering from sickle-cell anemia. That is an efficient and humane use of a racial category. Nonetheless, the origins of racial distinctions are to be found in culture and social structure, not in biology.

Race, then, is primarily a social construct. It has been constructed in different ways in different times and places. In 1870, the US Bureau of the Census divided the American population into races: White, Colored (Blacks), Colored (Mulattoes), Chinese, and Indian.16 In 1950, the census categories reflected a different social understanding: White, Black, and Other. By 1980, they reflected the ethnic blossoming of the previous two decades: White, Black, Hispanic, Japanese, Chinese, Filipino, Korean, Vietnamese, American Indian, Asian Indian, Hawaiian, Guamanian, Samoan, Eskimo, Aleut, and Other. In the 2000 census, the US government began to allow a person to report more than a single racial identity—a radical change brought about by the multiracial movement and the rising consciousness of racial multiplicity among the American public.17 In 2010, the categories were “White; Black or African American; American Indian or Alaska Native—Print name of enrolled or principal tribe); Asian Indian; Chinese; Filipino; Japanese; Korean; Vietnamese; Other Asian—Print race, for example, Hmong, Laotian, Thai, Pakistani, Cambodian, and so on; Native Hawaiian; Guamanian or Chamorro; Samoan; Other Pacific Islander—Print race, for example, Fijian, Tongan, and so on; Some other race.” This was complicated, of course, by the fact that people were allowed to check more than one box, so an elaborate system was devised to try to record both the numbers of people who placed themselves monoracially in each category and those who checked more than one box.18

In England in 1981, the categories were quite different: White, West Indian, African, Arab, Turkish, Chinese, Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan, and Other—because the sociopolitical landscape in England demanded different divisions.19 Thirty years later, the British census categories were

• White: English/Welsh/Scottish/Northern Irish/British; Irish; Gypsy or Irish Traveller; Any other White background, please describe;

• Mixed/Multiple ethnic groups: White and Black Caribbean; White and Black African; White and Asian; Any other Mixed/Multiple ethnic background, please describe;

• Asian/Asian British: Indian; Pakistani; Bangladeshi; Chinese; Any other Asian background, please describe;

• Black/African/Caribbean/Black British: African; Caribbean; Any other Black/African/Caribbean background, please describe;

• Other ethnic group: Arab; Any other ethnic group, please describe.20

In South Africa, there were five racial categories: White, African, Coloured, Asian, and Other.21 In Brazil, the gradations between Black and White were many: preto, cabra, escuro, mulato escuro, mulato clara, pardo, sarará, moreno, and branco de terra.22 Each of these systems of racial classification reflects a different social, economic, and political reality. Such social situations change, and so do racial categories.

Social distinctions such as race and class come about when two or more groups of people come together in a situation of economic or status competition. Frequently such competition results in stratification—in the domination of some groups by others. In the era of the transatlantic slave trade, people in Africa did not experience their lives as Africans or as Blacks; they were Hausa or Ibo or Fon, or members of any of several other groups. But when they were brought to America they were defined as a single group by the Europeans who held power over their lives. They were lumped together as Africans or Negroes or Blacks, partly because they shared certain physical similarities, especially when contrasted with Europeans, and partly because they shared a common status as slaves.23

From the point of view of the dominant group, racial distinctions are a necessary tool of dominance. They serve to separate the subordinate people as Other. Putting simple, neat racial labels on dominated peoples—and creating negative myths about their moral qualities—makes it easier for the dominators to ignore the individual humanity of their victims. It eases the guilt of oppression. Calling various African peoples all one racial group, and associating that group with evil, sin, laziness, bestiality, sexuality, and irresponsibility, made it easier for White slave owners to rationalize holding their fellow humans in bondage, whipping them, selling them, separating their families, and working them to death.24 The function of the one-drop rule was to solidify the barrier between Black and White, to make sure that no one who might possibly be identified as Black also became identified as White. For a mixed person, then, acceptance of the one-drop rule means internalizing the oppression of the dominant group, buying into the system of racial domination.

Race is by no means only negative, however. From the point of view of subordinate peoples, race can be a positive tool, a source of belonging, mutual help, and self-esteem. Racial categories (and ethnic categories, for they function in the same way)25 identify a set of people with whom to share a sense of identity and common experience. To be a Chinese American is to share with other Chinese Americans at least the possibility of free communication and a degree of trust that may not be shared with non-Chinese. It is to share access to common institutions—Chinese churches, Chinatowns, and Chinese civic associations. It is to share a sense of common history—immigration, work on the railroads and in the mines of the West, discrimination, exclusion, and a decades-long fight for respectability and equal rights. It is to share a sense of peoplehood that helps locate individuals psychologically, and also provides the basis for common political action. Race, this socially constructed identity, can be a powerful tool, either for oppression or for group self-actualization.

AT THE MARGINS: RACE AS SELF-DEFINITION

Where does this leave the person of mixed parentage? Such people have long suffered from a negative public image. In 1912, the French psychologist Gustave LeBon contended that “mixed breeds are ungovernable.” The American sociologist Edward Reuter wrote that “the mixed blood is [by definition] an unadjusted person.” Writers and filmmakers from Thomas Nelson Page to D. W. Griffith to William Faulkner have presented mixed people as tormented souls.26 Yet even if such a picture of pathology and marginal identity has ever been partially accurate, it certainly is no longer the case.

What is a person of mixed race? Biologically speaking, we are all mixed. That is, we all have genetic material from a variety of populations, and we all exhibit physical characteristics that testify to mixed ancestry. Biologically speaking, there never have been any pure races; all populations are mixed.

More to the point is the question of to which socially defined category people of mixed ancestry belong. The most illogical aspect of all this racial categorizing is not that we imagine it is about biology. After all, there is a biological component to race, or at least we identify biological referents—physical markers—as a kind of shorthand to stand for what are essentially socially defined groups. What is most illogical is that we imagine these racial categories to be exclusive. The US Census form said, until the 2000 census, “Check one box.” If a person checked “Other,” his or her identity and connection with any particular group was immediately erased. Yet what was a multiracial person to do?

Once, a person of mixed ancestry had little choice. Until fairly recently, for example, most Americans of part Japanese or part Chinese ancestry had to present themselves to the world as non-Asians, for the Asian ethnic communities to which they might have aspired to be connected would not have them.27 For example, in the 1920s, seven-year-old Peter fended for himself on the streets of Los Angeles. He had been thrown out of the house shortly after his Mexican American mother died, when his Japanese American father married a Japanese woman, because the stepmother could not stand the thought of a half Mexican boy living under her roof. No Japanese American individual or community institution was willing to take him in because he was not pure Japanese.28

On the other hand, the one-drop rule meant that part Black people were forced to reckon themselves Black. Some might pass for White, but by far the majority of children of African American intermarriages chose or were forced to be Black. A student from a mixed family described his feelings in the 1970s: “At home I see my mom and dad and I’m part of both of them. But when I walk outside that door, it’s like my mom doesn’t exist. I’m just Black. Everybody treats me that way.” When he filled out his census form, this student checked the box next to “Black.”29

The salient point here is that once, before the last third of the twentieth century, multiracial individuals did not generally have the opportunity to choose identities for themselves.30 In the 1970s and particularly the 1980s, however, individuals began to assert their right to choose their own identities—to claim belonging to more than one group, or to create new identities. By 1990, Mary Waters could write, “One of the most basic choices we have is whether to apply an ethnic label to ourselves.” She was speaking of a choice of ethnic identities from among several White options, such as Italian, Irish, and Polish. Yet the concept of choice began to apply to mixed people of color as well.31

Some even dared to refuse to choose. In 1985, I observed a wise five-year-old. Dining with her family in Boston’s Chinatown during Chinese New Year, she was asked insistently by an adult Chinese friend of the family, “Which are you really—Chinese or American?” It was clear the woman wanted her to say she was really Chinese. But the girl replied simply, “I don’t have to choose. I’m both.” And so she was.

This child probably could not have articulated it, but she was arguing that races are not types. One ought not be thrust into a category: simply Chinese or simply American, simply White or simply Black. Her answer calls on us to move our focus from the boundaries between groups—where we carefully assign this person to the White category and that person to the Black category—to the centers. That is, we ought to pay attention to the things that characterize groups and hold them together, to the content of group identity and activity, to patterns and means of inclusiveness and belonging. A mixed person should not be regarded as Black or White but as Black and White, with access to all parts of his or her identity. In the poem presented at the outset of this essay, Joseph Cotter’s mulatto felt the pull of the various parts of his heritage but felt constrained to choose only one. Since the 1990s, that choice has still been available to mixed people, but it has no longer been necessary. In the twenty-first century, a person of mixed ancestry can choose to embrace multiple parts of his or her background. Many of the essays in this volume are about the issues attendant upon recognition of a multiracial identity. As the essays attest, the patterns of identity making and claiming are sometimes quite complex, but the one-drop rule no longer need automatically apply.

NOTES

1. Maria P. P. Root, Racially Mixed People in America (Newbury Park, CA: Sage, 1992), 12–20.

2. www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/jefferson/mixed/spickard.html (retrieved August 11, 2013).

3. Joseph Seamon Cotter, Jr., Complete Poems, ed. James Robert Payne (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1990; orig. 1918), 27.

4. Carolus Linnaeus, Systema Naturae (1758), translated as The System of Nature (London: Lackington, Allen, 1806); Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, On the Natural Varieties of Mankind (New York: Bergman, 1969; orig. English 1865; orig. German 1775); Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, The Anthropological Treatises of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (Boston: Milford House, 1973; orig. 1865); Arthur de Gobineau, The Inequality of Human Races (New York: Fertig, 1999; orig. English 1915; orig. French 1853–55); Michael D. Biddiss, Father of Racist Ideology: The Social and Political Thought of Count Gobineau (New York: Weybright and Talley, 1970); Michael D. Biddiss, ed., Gobineau: Selected Political Writings (New York: Harper and Row, 1970). For other leading early racial theorists, see Georges-Louis Leclerc, comte de Buffon, A Natural History, General and Particular, 2nd ed. (London: Strahan and Cadell, 1785); and Georges Léopold Cuvier, Le règne animal (1817), translated into English as Animal Kingdom (London: W. S. Orr, 1840).

This vector was carried into the twentieth century by, among others, William Z. Ripley, The Races of Europe (New York: Appleton, 1899); A. H. Keane, Ethnology (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1901); Madison Grant, The Passing of the Great Race or The Racial Basis of European History (New York: Scribner’s, 1916); Madison Grant and Charles Stewart Davison, eds., The Alien in Our Midst, or “Selling our Birthright for a Mess of Pottage” (New York: Galton, 1930); Lothrop Stoddard, The Rising Tide of Color against White World Supremacy (New York: Scribner’s, 1920); Lothrop Stoddard, The Revolt against Civilization: The Menace of the Under Man (New York: Scribner’s, 1923); Lothrop Stoddard, Racial Realities in Europe (New York: Scribner’s, 1924); Lothrop Stoddard, Clashing Tides of Colour (New York: Scribner’s, 1935); Earnest Albert Hooton, Apes, Men and Morons (New York: Putnam’s, 1937); Earnest Albert Hooton, Twilight of Man (New York: Putnam’s, 1939); Carleton Stevens Coon, The Races of Europe (New York: Macmillan, 1939); Carleton Stevens Coon, The Story of Man (New York: Knopf, 1954); Carleton Stevens Coon, The Origins of Races (New York: Knopf, 1962); Carleton Stevens Coon, The Living Races of Man (New York: Knopf, 1965); Carleton Stevens Coon, Racial Adaptations (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1982).

The tradition continues in current generations: Jerome H. Barkow, Leda Cosmides, and John Tooby, eds., The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992); Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray, The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (New York: Free Press, 1994); Samuel P. Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996); J. Philippe Rushton, Race, Evolution, and Behavior, 3rd ed. (Port Huron, MI: Charles Darwin Research Institute Press, 2000); Patrick J. Buchanan, The Death of the West: How Dying Populations and Immigrant Invasions Imperil Our Country and Civilization (New York: St. Martin’s, 2002); Richard Lynn, Race Differences in Intelligence: An Evolutionary Approach (Augusta, GA: Washington Summit Publishers, 2006); Nicholas Wade, A Troublesome Inheritance: Genes, Race, and History (New York: Penguin, 2014).

For analysis and critique, see Stephen Jay Gould, The Mismeasure of Man, rev. ed. (New York: Norton, 1996); Joseph L. Graves Jr., The Emperor’s New Clothes: Biological Theories of Race at the Millennium (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001); Jonathan Marks, Human Biodiversity: Genes, Race, and History (New York: Aldine de Gruyter, 1995); Ashley Montagu, Man’s Most Dangerous Myth: The Fallacy of Race (New York: World, 1964); Thomas F. Gossett, Race: The History of an Idea in America (New York: Schocken, 1965); Audrey Smedley, Race in North America, 2nd ed. (Boulder, CO: Westview, 1999); William H. Tucker, The Science and Politics of Racial Research (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994); C. Loring Brace, “Race” Is a Four-Letter Word: The Genesis of the Concept (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005).

5. There were two ways of conceiving this hierarchy, depending on which side of the Darwinian divide one inhabited. Pre-Darwinians thought of Adam and Eve as Caucasians, with Asians, Africans, and Native Americans representing degenerated descendants in separate lines. Those who came after Darwin and embraced the evolutionary view conceived of the human races as part of a continuum of ever-improving species and races, with great apes succeeded by chimpanzees, then by Africans, Asians, and Caucasians. The last were seen as the most complex and perfect of evolution’s products. James C. King, The Biology of Race, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1981); Emmanuel Chukwudi Eze, ed., Race and the Enlightenment (Oxford: Blackwell, 1997); Ripley, Races of Europe.

6. Grant, Passing of the Great Race. The Nordics were people who could trace unmixed ancestry from Scandinavia, northern Germany, or the British Isles. Alpines were most minority peoples of Europe (Bretons, Basques, Walloons, etc.), French, southern Germans, northern Italians, Swiss, Russians, other Eastern Europeans, and so on. Mediterraneans included Iberians, southern Italians, northern Africans, Hindus, Persians, and many Middle Easterners.

7. The cephalic index was the ratio of the breadth of the head to its length, expressed as a percentage.

8. Henry Fairfield Osborn, writing in the New York Times, 1924; quoted in Jacques Barzun, Race: A Study in Superstition (New York: Harper and Row, 1965; orig. 1937), 224.

9. These ideas still had some currency as late as the 1980s. Consider a map in the 1982 Bartholomew World Atlas that divides up the world by skin color:

Light Skin Colour (Leocodermi)

Indo-European: White skin, straight to wavy hair

Indo-European: Light brown skin, wavy hair

Hamitic-Semitic: Reddish brown skin, wavy hair

Polynesian: Light brown skin, wavy hair

Yellow Skin Colour (Xanthodermi)

Asiatic or Mongolian: Yellow skin, straight hair

Indonesian: Yellow brown skin, straight hair

American Indian: Reddish yellow skin, straight hair

Dark Skin Colour (Melanodermi)

African Negro: Dark brown skin, kinky hair

Pigmy Negro: Brown skin, kinky hair

Melanesian: Dark brown skin, kinky hair

Australo·Dravidian: Brown to black skin, wavy to kinky hair

There is also a map dividing the world by cephalic index:

Dolichocephalic (Long-headed)—primarily the peoples of Africa, Arabia, India, and Australia

Mesocephalic (Medium-headed)—Northwest Europe, North America, China, Japan, Persia

Brachycephalic (Broad-headed)—the rest of Europe, Latin America, the rest of Asia

Hyperbrachycephalic (Very broad-headed)—Russia

What the mapmakers imagined they were measuring and classifying is unclear, but it is clear that pseudoscientific racism was alive in the 1980s. John C. Bartholomew, World Atlas, 12th ed. (Edinburgh: Bartholomew, 1982).

10. King, Biology of Race, 112. One must be careful of even this appeal to argument by scientists. Much of the allure of the Blumenbach argument was that it was put forth on the supposed basis of science. Since some people regard science with a kind of ritual awe, they are unable to think critically about any idea, however preposterous, put forth in the name of science.

11. Alice Brues, People and Races (New York: Macmillan, 1977), 1.

12. Paul Spickard, Mixed Blood: Intermarriage and Ethnic Identity in Twentieth-Century America (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989), 274–75; Gilbert T. Stephenson, Race Distinctions in American Law (New York: Appleton, 1910), 12–20.

13. King, Biology of Race, 156–57.

14. Ibid., 158.

15. Poppy Cannon, A Gentle Knight: My Husband, Walter White (New York: Rinehart, 1956); Walter White, A Man Called White (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1995; orig. 1948); Thomas Dyja, Walter White: The Dilemma of Black Identity in America (Chicago: Ivan Dee, 2008); Kenneth Robert Janken, White: The Biography of Walter White, Mr. NAACP (New York: New Press, 2003).

16. US Department of Interior, Population of the United States: Ninth Census, 1870 (Washington, DC, 1872), 606–9.

17. Joel Perlmann and Mary C. Waters, eds., The New Race Question: How the Census Counts Multiracial Individuals (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 2002); G. Reginald Daniel, More than Black? Multiracial Identity and the New Racial Order (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002); Kim M. Williams, Mark One or More: Civil Rights in Multiracial America (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006); Jayne O. Ifekwunigwe, ed., “Mixed Race” Studies: A Reader (New York: Routledge, 2004), 205–60; Maria P. P. Root, ed., The Multiracial Experience: Racial Borders as the New Frontier (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 1996), 15–48, 411–16.

18. www.census.gov/population/race/ (retrieved July 27, 2013). That some of these are also nationality labels should not obscure the fact that many in the United States and Great Britain treat them as domestic racial units, not simply statements of national origin.

19. Michael Banton, Racial and Ethnic Competition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 56–57. Different constituent parts of the United Kingdom (England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland) keep track of race and ethnicity in slightly different ways.

20. www.ons.gov.uk/ons/guide-method/measuring-equality/equality/ethnic-nat-identity-religion/ethnic-group/index.html#1 (retrieved July 27, 2013).

21. George M. Fredrickson, White Supremacy: A Comparative Study in American and South African History (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981).

22. Carl N. Degler, Neither Black nor White: Slavery and Race Relations in Brazil and the United States (New York: Macmillan, 1971), 103. See also G. Reginald Daniel, Race and Multiraciality in Brazil and the United States: Converging Paths? (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2006); Edward E. Telles, Race in Another America: The Significance of Skin Color in Brazil (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004).

23. Winthrop D. Jordan, White over Black: American Attitudes toward the Negro, 1550–1812 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1968); Michael A. Gomez, Exchanging Our Country Marks: The Transformation of African Identities in the Colonial and Antebellum South (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1998); Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, Slavery and African Ethnicities in the Americas (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

24. Fredrickson, White Supremacy; Jordan, White over Black.

25. Since both are defined on the basis of social and not biological criteria, a race and an ethnic group are in essence the same type of group. They reckon (real or imagined) descent from a common set of ancestors. They have a sense of identity that tells them they are one people. They share culture, from clothing to music to food to language to childrearing practices. They build institutions such as churches and fraternal organizations. They perceive and pursue common political and economic interests. See Stephen Cornell, The Return of the Native (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985); Spickard, Mixed Blood, 9–17; Paul Spickard and W. Jeffrey Burroughs, “We Are a People,” in We Are a People: Narrative and Multiplicity in Constructing Ethnic Identity (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2000), 1–19.

26. Gustave LeBon, La Revolution française et la psychologie des revolution (1912), 53, 68, quoted in Barzun, Race, 227; Edward Byron Reuter, Race Mixture (New York: Negro Universities Press, 1969; orig. 1931), 216; Spickard, Mixed Blood, 329–39.

27. This was true for people of mixed Jewish and Gentile background as well. They were shunned by Jewish people and institutions and typically had to adopt Gentile identities.

28. Spickard, Mixed Blood, 110–17; see also Catherine Irwin, Twice Orphaned: Voices from the Children’s Village of Manzanar (Fullerton: Center for Oral and Public History, California State University, Fullerton, 2008).

29. Spickard, Mixed Blood, 329–39, 360–61.

30. Sometimes the assignments were a bit arbitrary. The anthropologist Max Stanton tells of meeting three brothers in Dulac, Louisiana, in 1969. All were Houma Indians, had a French last name, and shared the same father and mother. All received their racial designations at the hands of the medical people who assisted at their births. The oldest brother, born before 1950 at home with the aid of a midwife, was classified as a Negro, because the state of Louisiana did not recognize the Houma as Indians before 1950. The second brother, born in a local hospital after 1950, was assigned to the Indian category. The third brother, born eighty miles away in a New Orleans hospital, was designated White on the basis of the French family name. I owe this information to a personal communication from Max Stanton in 1990; see also Max Stanton, “A Remnant Indian Community: The Houma of Southern Louisiana,” in The Not So Solid South: Anthropological Studies in a Regional Subculture (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1971), 82–92.

31. Mary Waters, Ethnic Options: Choosing Identities in America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), 52.