— 7 —

Many researchers, including some who know tigers well, would say that the tigers of Sundarbans are not real.

Of course, no one denies there are tigers here, with so many pugmarks stamped everywhere in the sand and the mud. But tigers who swim after boats to prey on people? Tigers who fly through the air? Tigers who before men’s eyes grow to twice their normal size? Tiger gods who must be propitiated with prayers and incense? These are the tigers that the people of Sundarbans know, and Western science says that such beings cannot exist: they are impossible. How can a swimming tiger rocket out of deep water onto the deck of a boat? How can a big mammal survive drinking nothing but salt water? How can an animal weighing up to five hundred pounds leap aboard a ten-foot wooden boat without rousing the entire crew? It’s as impossible as materializing from thin air.

But even impeccable sources report that the tigers of Sundarbans do not behave like the tigers at well-studied research sites.

George Schaller’s studies at Kanha and the Smithsonian project at Chitawan confirm that tigers typically hunt at night. That tigers evolved as night-hunters is mirrored in the tapetum lucidum, the light-gathering crystals of the retina, which cause their golden eyes to glow green in the moonlight, red in the beam of a torch. By daylight a tiger’s vision is considered to be about as sharp as a person’s, but at night, when the deer are most active, the tiger’s eyes are stronger than ours by sixfold.

During the glare and heat of the day, tigers typically prefer to rest, especially if the night’s hunt was productive. Often they “lie up” under cover next to the night’s gnawed-over kill. Chitawan researchers found that during the hot season (March to May), if they were able to locate a tiger by midmorning, they would find it in the same place one to six hours later, 82 percent of the time. Even in the cool season, when tigers are most active, the researchers could count on finding the tiger in the same spot one to six hours later well over half the time.

But Sundarbans tigers, by all accounts, hunt at least as often by day as by night. In fact, they seem to prefer to hunt people by day. When Kalyan Chakrabarti analyzed estimated times of death of people killed by tigers in Sundarbans, 80 percent of the reported casualties occurred during daylight hours, he claimed.

Fishermen, guides, and forest guards say that time of day matters little to the creatures of Sundarbans; water is what matters. Low tide spreads the water’s offerings like a banquet on the mud, drawing the chital, the monkeys, the wild boar, the jungle fowl, even the monitor lizards to investigate. This is the best time to see animals in Sundarbans, and no one knows this better than the tigers. So they hunt by the tides, careless of day or night.

Tigers everywhere can swim, and they enjoy water; in the hot season tropical tigers often rest in a cool stream. But in Sundarbans the tigers are as at home in water as on land. They are considered completely amphibious—the term appears again and again in the scant scientific literature about them.

Many normally land-bound creatures swim here. Monitor lizards, relatives of Komodo dragons, are excellent swimmers—at first sight they can be mistaken for crocodiles. The deer swim. The pigs swim. Even the monkeys swim. It is often said that monkeys and apes cannot swim—not even orangutans, our orange-coated cousins, who often wade in Indonesian swamps—but on one of our first days out with Girindra, we saw a rhesus macaque dog-paddling across a channel, a sight so strange Dianne and I could not even imagine that it was a monkey until the boat was almost on top of the animal.

Sundarbans tigers are strong, swift swimmers. Rathin told me he’d once clocked a tiger who swam 1,800 feet, against the current, in seven minutes, eighteen seconds. Rathin, lying on his belly on the bow of the boat, with his face and camera overhanging the swimming tiger, had ordered the launch to circle the animal; the tiger, he said, reared up out of the water, a full six inches higher than its swimming position, to snarl and hiss at him. Rathin says that the tail of the Sundarbans tiger is more muscular and consistently thicker at the base than that of other tigers; he says they use it as a limb for swimming, in the sinuous, sweeping, side-to-side manner of the crocodile.

Sundarbans tigers may even hunt in the water. No one knows, for no one has recorded seeing a Sundarbans tiger kill anything but a member of the observer’s own party. These tigers do love fish, though, and their scats sometimes glitter with silvery scales. But they could also hunt fish from the shoreline, as do Sundarbans’ little-known fishing cats, who bat fish from the water with their odd, nonretractable claws.

Sundarbans tigers may also differ from tigers elsewhere in the way they feel about territory. Both Schaller and the Smithsonian’s Mel Sunquist found that the tigers they studied literally owned property: in the scientists’ words, they maintained “a land tenure system based on prior right.” All the tigers in their studies observed this rule: occupancy confers rights to an area, and these rights are respected by all for several years, if not for the life of the resident. At the study sites the range of each tiger or tigress is not shared by any other adults of the same sex, although a tiger’s territory may overlap those of three to six tigresses. Female offspring may inherit their mother’s range.

Resident tigers do not defend or patrol their land per se, the Kanha and Chitawan studies showed. Instead, residents spend a great deal of time and effort advertising their presence: they etch their claw marks deep into the bark of trees. They leave neat piles of dung in prominent spots—often on a road. With tail held high, they spray urine backward onto tree trunks and tall tufts of grass. David Smith likens the scent to that of buttered popcorn. Schaller learned to detect the smell even three months after it was first sprayed, though resident tigers are careful to refresh their scent every few weeks.

If a territory is unused for a month, other tigers consider it vacant and may move in. For this reason, a resident will visit most parts of its range every few days to every two weeks. These travels, Sunquist stressed, are not always hunting expeditions: the tigers include in their ranges “nonproductive” areas, like sal forest, where they are unlikely to find meat. Tigers use these areas as buffer zones between their own and other residents’ land, and as access corridors to other parts of their territory.

Similar land tenure systems have been documented in mountain lions, jaguars, leopards, bobcat, and lynx—all of whom, like tigers, although acutely aware of one another’s identities and activities, spend most of their time alone.

But Sundarbans tigers’ territories, if they exist at all, may be completely different. About half of the area is under water. Can an amphibious cat own water as well as land? If so, how would one declare ownership? About this we know nothing.

Some of Sundarbans Tiger Reserve’s experts feel strongly that these tigers do not maintain territories at all. Pranabesh Sanyal points out that in vast portions of the lands they roam, the scent and scats tigers use to tag their territories would be washed away daily by the tides. Others, like Kalyan, say that Sundarbans tigers are territorial. He says they carefully scent-mark only those areas they know will not be inundated by high tide. Still others suggest that these tigers may be hyperterritorial. The constant washing away of their scent-marking, in fact, could account for their extraordinary aggression toward intruders.

“The Sundarbans is a peculiar place, very unlikely tiger habitat,” notes Peter Jackson, the World Conservation Union–IUCN cat specialist. He visited Sundarbans in 1986 to make a film with the BBC. He saw only one tiger there—it came to drink at a watchtower water hole at dusk—but, he says, these animals do seem different from the many dozens of tigers he has observed elsewhere in India and other parts of Asia. “Obviously these tigers must have been cut off from tigers in other habitats by the destruction of local forests for many, many years.” Evolving in isolation, this group may have established—or preserved—a system of behavior, a culture, different from that of all other tigers on earth.

But no one knows. No formal long-term studies have ever been attempted here. No one knows how far the tigers range. No one knows how long they live. No one even knows how many there are. For the methods that have served science so well at Kanha and Chitawan simply do not apply in Sundarbans.

When I was planning my first trip to Sundarbans, I asked George Schaller what he thought of the place. As part of a brief comparative study to complement his Kanha data, he had visited Sundarbans for three days. He had immediately rejected it as a study site, he said; it was too densely forested to spot tigers, much less follow them. “Don’t go there,” he told me, wrinkling his nose and frowning. “You won’t see any tigers in Sundarbans. If you want to see tigers, go to Kanha.”

This I did. Shortly after arriving in Calcutta, and before our trip to the Indian side of Sundarbans, Dianne and I traveled to the site of Schaller’s landmark study: a great green and gold expanse of sal and bamboo forests, tall grasslands, deep ravines, and low hills in central India. This is the idyllic, wild India we most often see in nature films; Belinda Wright filmed most of her Emmy Award–winning Land of the Tiger here. Chital gather in herds of several dozen; rutting seven-hundred-pound sambar stags garland their antlers with sal leaves; and the electric green, lyrically named blossom-headed parakeets streak through the sky.

Walking through Kanha’s meadows and along its forest roads or watching from his Land Rover, Schaller was sometimes able to observe tigers for half an hour—longer if the tiger was on a kill. A kill provided a social occasion for the usually solitary cats, and several times Schaller observed two families—two tigresses and their cubs—share a meal. Sometimes he staked out a live animal as bait while he waited in a blind. One evening he watched a tigress teaching her cubs to kill a tethered buffalo.

Baits no longer are used to lure tigers for observation in India. But today it is easy to see a tiger at Kanha. Protected by national decree and conditioned by decades of tourism, Kanha’s tigers are far less wary of people than they were in Schaller’s day. Early each morning park staff on specially trained elephants locate tigers and then return midmorning to meet the tourists waiting at the information center. In two days Dianne and I saw a tigress and her year-old cub, and a tiger lying up with his kill.

The elephants, despite their great bulk, seem to float through the forest like clouds. (Hindu mythology in fact holds that elephants were once winged and, like clouds, roamed freely in the sky; white elephants are thought to be able to produce clouds.) Because of the structure of the bones of their feet, elephants walk on tiptoe; their footprints may be shallower than a tiger’s. With their careful, shallow steps, the elephants inspire their passengers to silence and reverence. The morning we visited the tiger on his kill—a chital doe whose shoulder he had already eaten—twenty-two carloads of tourists were packed in silently on the backs of elephants. Tapping instructions with his bare heels against her head, the mahout asked the elephant to move this way and that for various camera angles. Shutters clicked furiously, but no one spoke. The tiger looked up at us with golden eyes, serene and dispassionate as a statue.

For centuries, Rajput, Mogul, and then British shikaris hunted tigers from elephant back, enjoying both relative safety and a fine vantage point from which to search for game. Elephants have proved equally practical for research. Smithsonian researchers used trained elephants to drive tigers off their kills and toward trees where men waited with dart guns. After darting the tiger, they weighed and measured the animal, examined it for injuries, collected its ticks. They measured the canines and removed an incisor—sectioning it can determine the animal’s age. Five to seven hours later the tiger would awake with a tattoo and a radio collar. Thereafter, on elephant back, from a Land Rover, from a plane, or on foot, researchers can follow that individual and map its movements. With a hand antenna, listening for the kissing sound of the radio signal in the earphones, the researcher notes the direction of the loudest sound. From another point a second direction is noted, and where the lines cross the researchers locate the tiger.

But such work is not possible in Sundarbans. Elephants can’t be used. (For one thing, there is no way to transport them in, and no wild elephants are known to have existed here, though there once were rhinos.) Neither can you use Land Rovers, since there are no roads. Radiotelemetry won’t function here: it works only on fairly open ground, like the meadows at Kanha or the tall-grass terai of Chitawan. Trees blot out the signal.

The one standard tool available to Sundarbans’ researchers is the dart gun. But even darting tigers does not seem to work here as well as it does at other study sites.

In his first year as Sundarbans field director, Pranabesh Sanyal was called to tranquilize a tigress who had entered a villager’s cattle shed. When Dianne and I visited him at Buxa Tiger Reserve, a planted teak and sal forest where he is now field director, we shared tea on the porch of one of the bungalows while he told us the story by lantern light:

“By local inquiry we found that the previous morning, when the cowherd was about to let out the cattles, the boy had found this tigress was there. Immediately the boy came out and locked the door! So the villagers were dispatched to call us from Gosaba, which has a telephone to the trunk line at Canning.”

Pranabesh got the call at six P.M.; by ten he had reached the village of Uttarbanga and slogged his way through half a kilometer of mud in the dark. There was the tigress, still in the cattle shed.

“That night we found a very peculiar thing,” Pranabesh said. “Normally, to tranquilize a tiger you use five milliliters of Ketaset. But we used our first dose, and no reaction. Then we used another five milliliters. It had no effect. We were scared. There were about one thousand spectators there, and the tigress was trying to come out of the cattle shed! Then, of course, we tried ten milliliters—twenty milliliters in all. But there was still no effect.”

No one seemed to know what to do. Then the field director’s boatman stepped forward. His name was Ben Behari—Jungle Walker. “At that time, as the tigress was trying to come out,” said Pranabesh, “he took a small bamboo stick, long but slender, and tapped her on the nose three times.” At this the tigress lay down.

I asked him how Ben Behari knew to do that. Did he know why it had worked? Was Ben Behari some sort of shaman? Pranabesh bobbled his head from side to side in that Eastern not-quite-nod, not-quite-headshake, neither yes nor no that so confuses Westerners. “I don’t know how he got that in mind,” Pranabesh said, “but it worked.”

Then, by hand, Ben Behari put a five-milligram Valium tablet in the tigress’s mouth. He brushed her eyelids closed. The men loaded her into a cage, and she was taken to the Calcutta zoo, where she was named Sundari.

How can you study an animal you cannot see? How can you manage an unseen population?

Most of the time in Sundarbans you cannot see the tiger. Neither can you see the gods or the wind, but you can see what they have touched. And for many years, this was what the West Bengal Forest Department relied upon: in attempting to trace the outlines of the tiger’s mystery, the men looked for impressions in the mud.

Until 2007, the tiger census, conducted once every two years at each of India’s twenty-one tiger reserves, was based on the premise that every tiger’s footprint is as individual as a human fingerprint. Shikaris used this method to track individual man-eaters. Expanding on the idea, India’s tiger experts developed a way to identify and therefore count each individual. From these tracks Indian officials, like palmists, tried to trace the fates of the country’s tigers since the creation of the network of tiger reserves in 1972.

Almost all of the 130 people on the staff of India’s Sundarbans Tiger Reserve—officers, forest guards, cooks, orderlies—were involved in the census. They traveled in hundred-foot launches like Monorama, with its powerful forty-horsepower engine and tall, whiplike radio antenna and porcelain sink; they took smaller boats with names like J’ai Guru, powered by ten-horsepower all-purpose generators; they used dinghies and motorboats; even the Forest Department’s eighteen houseboats, on which the patrolling staff lived in squalid good humor, set sail.

There was an air of gaiety as the enumerators and their support staff left for the thirty-seven field recording camps where they would work for six days. One hundred or so volunteers were recruited to help count the tigers; extra boatman were hired from Sundarbans villages to ferry the 250 enumerators to their work sites. Aboard the boats each night there would be long lamp-lit card games, country liquor, and laughter.

Each team of five or six enumerators left the boat at ebb tide, when the widest swath of land was exposed. Each was equipped with a set of two rectangular clear glass plates, 20 by 25 centimeters, held together by screws at the corners; a felt-tip pen; a one-meter steel tape; paper; and two rubber bands. This comprised the Tiger Tracer, with which they would attempt to identify every unseen tiger in the reserve’s 998 square miles.

Seven months after the December 1992 census was conducted, the Forest Department released the figures to the state minister for environment and forests. It reported 251 tigers in the Indian Sundarbans. In the 613 paw-print tracings collected, they counted 92 individual tigers, 132 tigresses, and 27 cubs.

For years, these census figures were credited with such precision that even small changes were scrutinized. Compared with the figures released two years before, the 1992 census reported a decrease of 18 animals. “Only 250 tigers left in the Sundarbans,” headlined the Calcutta Telegraph. (The article also reported that 295 tigers had been counted in 1988, and only 196 in 1990—a decrease that should have been far greater cause for alarm. The Forest Department’s figures were actually 265 in 1988 and 269 in 1990.) But Rathin, then a sixteen-year veteran of government service, was ready for that. The report he prepared for the ministry assured them the decrease was merely an artifact of previous, less-accurate estimates. “However, this estimate,” he wrote, “has a definite aura of authenticity.”

In the dry dust along a dirt road you can learn in a few hours to tell the sex of a tiger who has recently passed by: the print of the male’s hind foot is squarer than that of the female; his four toes are also shorter and blunter. At parks like Kanha and Ranthambhore fresh pugmarks are etched into the dust along the roads with the precision a detective would wish for in dusting for fingerprints. (Tigers seem to like traveling on roads.) Often there are other characteristics that help distinguish one individual’s pugmarks from another’s. At Chitawan one tigress’s distinctive prints earned her the name Chuchchi, or “pointed toes.” The shape of the three lobes of the paw pad, too, may be unique. Where the lobes join, two conically tapering valleys in the pad leave ridges in the dirt. A good, clear print in light dust will show very well defined tips of these ridges in the bottom line of the pugmark.

On my second trip to India I met Raghu Chundawat, an instructor with the prestigious Wildlife Institute of India. He was teaching the Tiger Tracer technique to park staffers around the country. I met Raghu at Ranthambhore, a spectacular tiger reserve in Rajastan, gathered around the remains of a thousand-year-old fort and neck-laced with lakes. Here the young, mustached teacher was instructing park research officers in the fine points of identifying individual tracks.

“You must pick your pugmarks carefully,” he advised as he leaned over a four-toed impression in the dust. “Only a perfect print will do.” He stressed how you must place the glass Tiger Tracer right on top of the print. You must position your eyes and your pen directly over the portion you are tracing—otherwise parallax error will grossly distort the outline. You must be wary of glare and shadow. You must pay particular attention when tracing the flat edge of the top of the pad, the pad’s lobes, the tips of the toes.

There were, in fact, more than a dozen “parameters” considered “diagnostic” of an individual print, but any of them could be distorted by the slightest glitch. A piece of gravel underfoot can cause a pugmark to twist or splay. Wet ground will grossly enlarge a print; claw marks, as the cat tries to gain purchase on slippery ground, further distort it. “For instance,” he continued, “this pugmark here”—it was decidedly smaller than the prints headed in the opposite direction along the road, which we had identified as belonging to an adult tiger. “Is this a female or a cub?” Raghu asked. The heel impression indicated the animal had a problem with its feet, causing it to place more weight on the outside of the heel—but as we followed the track we saw that this was not consistent.

“These kinds of individuals create confusion,” he said, tracing the footprint onto paper. So, I asked, how do you resolve the confusion? How can you identify this individual if the pugmarks aren’t consistent? “This,” he answered, “is the art.”

Even under ideal conditions, reading the subtleties of the tiger’s paw is difficult. At a normal walking pace on hard ground, a tiger places its hind paw exactly where the front paw of the same side has just trod, creating a double print. Tracking tigers at Ranthambhore, Harsh Vardan and T. K. Bapna claimed that a tiger “may leave pugmarks of differing size and style as he or she may walk in a different mood, to chase a prey or to hide itself.”

Was the Tiger Tracer’s art reliable enough to produce an accurate count of individuals? Many researchers have doubted this for quite some time. The Smithsonian research team at Chitawan concluded “it was not usually possible to relate tracks to specific individuals except in cases [such as Chuchchi’s] where the animal had an unusual track pattern.” Often they would find no tracks from a tiger that their radio telemetry told them was in fact quite nearby. The method was not used for the nationwide tiger census in 2007.

Even earlier, though, at many of India’s tiger parks, officials used the Tiger Tracer only as a supplement to other methods. Researchers assumed that over three days of round-the clock watches in the dry season, every tiger in a given reserve would come to drink at a water hole. At some parks, like Kanha and Ranthambhore, researchers claimed to know every tiger on sight by their individual cheek stripes.

But in Sundarbans the enumerators relied on prints alone. And in the sloppy, slushy silt, most pugmarks look like formless holes punched in the mud.

Sundarbans resists the prying eyes of scientists. Like the guardian of some underworld, a crocodile might lurch from the water and grab you; a tiger could leap at you from land or water; as you wade ashore from a dinghy, sharks may attack. There are six species of shark here, including aggressive tiger sharks that grow to eighteen feet. There are deadly snakes, including those most dreaded by Westerners: the banded krait and Russell’s pit viper. But the locals know others that are just as dangerous: the greenish shutanuli, which is said to drop from the trees and sting your head with its tongue, and the kalash, which crawls into your bed at night. And in the water there are sea snakes with paddle-shaped tails, whose venom is ten to forty times as toxic as the cobra’s.

Any time, but especially from August to November, cyclones may rake the shores. The winds have been clocked at 112 miles per hour. Small animals are blown for miles, and for days after a big cyclone the bloated bodies of human victims collect at jetties. They are so numerous that the forest staff has to push the bodies away with bamboo poles so that they float downstream.

In November of 1988 a cyclone struck just as the boats were converging for the tiger census. A large Forest Department launch, the Rangabilia, sank, drowning the officers aboard. A team of divers from Madras were hired to look for the sunken ship, but they never found it. The silt of the creek bottom, they said, was as soft and loose as quicksand. Sundarbans swallows its victims whole.

Subtler dangers wreak yet more damage. Rathin told me that an unusually large number of his staff go blind. He has learned from a doctor that a certain fly lives here that is attracted to the human eye. “Thik! It flits in to lay its eggs,” he warned me. Fifteen years later the eggs hatch, and by then “there is nothing you can do about it.”

The waters here seethe with disease. The Forest Department gets drinking water from tanks near Canning—somewhat muddy and salty but potable. But you can get sick from the river water even if you don’t drink it. When we visited the Bangladeshi side of Sundarbans, a French lady with whom we traveled, whose husband was posted in Dacca with the World Bank, dipped her finger into the river water to taste how salty it was; within six hours, while she sat in a car on the ferry to Bagherhat, she was seized with such violent diarrhea that it burst through her dress and covered the back seat. She needed immediate injections of antibiotics; had we not already been on our way out of Sundarbans when she fell ill, she might have died.

In the face of these daily dangers the West Bengal Forest Department has neither the money nor the technology to conduct Western-style science. This is one of India’s poorest states, and the department’s resources are almost unbelievably meager. Though this is one of the most snake-infested areas on earth, the department has only one polyvenom antivenin syringe. And the serum in it has probably gone bad. Antivenin must be kept refrigerated, so it cannot be carried on Forest Department boats; only the police station at Gosaba has a kerosene-powered refrigerator. If that refrigerator should run out of kerosene for even one day, the antivenin in it would become useless.

Understandably, the gadgetry available to Western researchers—computers, radio collars, satellite telemetry—seems dazzling to the few Bengali researchers who have tried to study the tigers of Sundarbans. What if Western-style technology could be used to explore the lives of the Sundarbans tigers? Kalyan, who has a Ph.D. in ecology and a master’s degree in statistics, has been considering this question ever since he visited Bristol, England, on a fellowship in 1986.

“In the U.K. they are telling me that even mental processes can be found out by computer!” he told Dianne and me when he visited us at the Tollygunge Club.“A person who is a criminal, and a person who is good, you can find out by their brain signals who is really a criminal! And if this is possible for man, it is possible for animals. I am quite sure. I am quite sure.”

We listened, amazed, as Kalyan proceeded to outline what he believed could be done if the wonders of computers and telemetry could be brought to Sundarbans’ forests:

“I think what should be done is, there should be a radio monitoring system, some kind of a collar put on, that gives a signal of the tiger’s thought processes,” he said, quite excited and very serious. “And also, the person who is going into the forest, their thought processes should also be monitored through a computer. A kind of monitoring system could be developed, and by comparing the thoughts of a person and the tiger, we could come to a very good conclusion in reducing human casualties: we could find what a tiger thinks before he goes to kill a human being, and what that person is thinking. Either could be thinking in some particular manner—and if we got that particular signal, the person could be saved.”

Of course this is science-fiction fantasy. No one has developed a machine that can monitor thoughts. Not even conventional telemetry can be used in Sundarbans because the trees would block the signal; the monsoon humidity would fritz any computer; and even if they could work under such conditions, the Forest Department could never afford them.

But Kalyan’s view is informative. What he is saying is that he would not use these machines as Westerners might, to map the ranges and movements of the study subjects—but instead to discover what lies in the heart and mind of the tiger.

“Superstition and supernatural qualities attributed to the tigers, however fictitious they may appear, have their basis in fact,” A. B. Chaudhuri and Kalyan wrote in the paper they delivered at the 1979 International Symposium on Tiger.

In the paper they reported aspects of their studies that have never been published in Western peer-reviewed journals. After interviewing local people, they wrote that frequently the Sundarbans tiger was able to solve the problem of entering boats by “getting airborne, raising its body in mid-air and effecting a smooth landing.” They reported as “a strange fact”—but a fact nonetheless— that in the tiger’s jaws “the human body, with less of life, contracts to about half its size, enabling the man-eater to carry it away with ease.”

The world of Sundarbans, as even these educated men see it, is held together by a web of enchantment. Sometimes the face of the sea glows with the fluorescence of marine microorganisms called dinoflagellates, and the forest flashes with fireflies. The two researchers asked, “Do the man-eaters derive extra energy or impetus to prowl at night and search for human prey ... due to this incredible bioluminescence?’

On several of the nights I would spend on Monorama over the coming months, Rathin and I often stayed up on deck to look for fireflies and bioluminescent waves. We were never sure whether the silvery shine on the water was the moon’s reflection or the glowing spirits of little creatures in the water. Sometimes in the forest we saw points of light, but we were never sure if they were fireflies or eyeshine or moonlight glinting off the dew. Or perhaps something else entirely.

“So many people have died in Sundarbans,” Rathin said to me one night, “that people say the forest is full of their spirits.”

But Rathin, who wears the Christian cross his parents gave him on a leather thong around his neck, says he doesn’t believe such things. He is, he insists, a modern man and does not believe in spirits. Instead he consults a Dell paperback for his horoscope to see whether the day will be favorable or unfavorable. He is careful to subtract ten hours for each forecast, he told me, to make up for the time difference between India and America, where the book was printed. The idea that stars affect our fates is both logical and scientific, Rathin explains, for the planets and stars physically pull upon the bodily fluids of all human beings. “From the moment of birth these forces are pulling, and the effect is as real as the moon on the tides,” he says.

Rathin’s staff, however, consults forces closer to earth. Each evening aboard Monorama one of the lungi-clad boatmen wedges sticks of incense between the boards at the head of the boat and inside the wheelhouse and utters his prayers. Each time I slept in the cabin I was moved to find that someone had kindly placed incense there for me as well. Its sweet scent smoldered a prayer to the gods, a plea for the well-being of the next day’s expedition.

And when the enumerators gathered for the tiger census in Sundarbans, the research officer would often kneel to gently touch the first print he found. Before setting the Tiger Tracer upon a pugmark, he would bring his right hand from the print to his forehead and then to his heart, silently honoring the tiger god.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

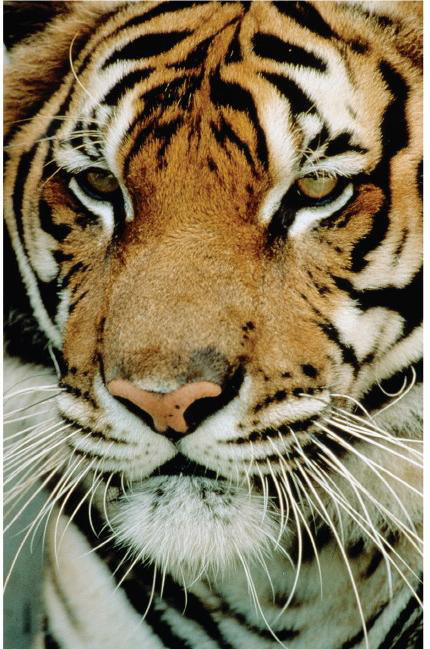

The tiger is the largest, the strongest, and the most beautiful of the giant cats—the only one with a coat of flame, burning bright.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

When we traveled aboard the large government launch Monorama, we often woke to misty dawns as the river turned to sky.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

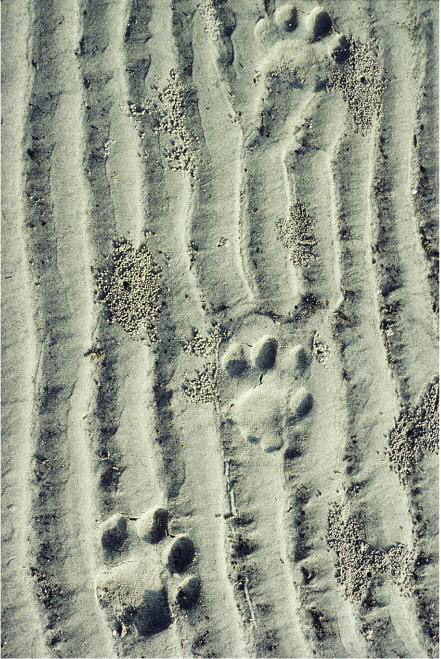

On the sand beaches of the Bay of Bengal, you can often see the footprints of a tiger.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

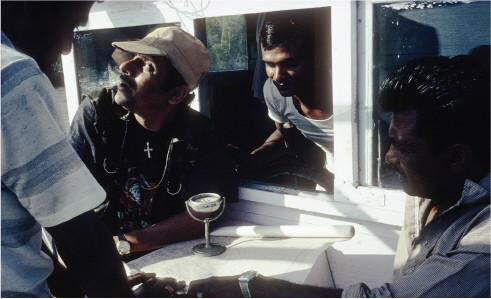

Aboard Monorama Rathin (wearing cap) pores over the map of Sundarbans as he debates the route with Girindra Nath Mridha, at right, and Forest Department staff.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

The white spots on the back of a tiger’s ears, some think, might act as flags to help cubs follow the mother.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

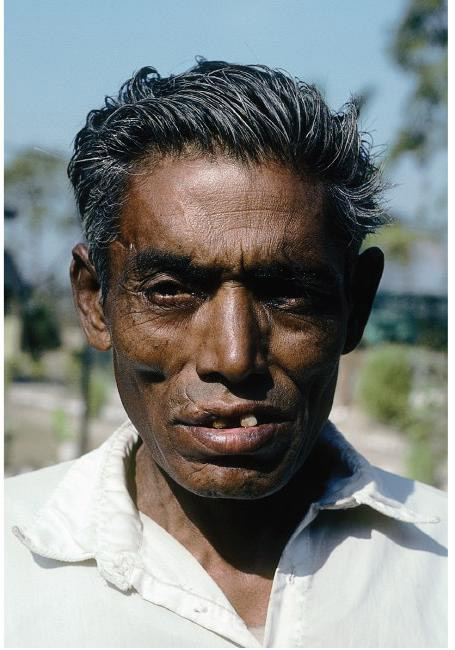

Phoni Guyan, a powerful gunin, bears scars from a tiger attack in 1984. He survived, but the tiger killed another man in the party and carried the body off into the forest.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

I could barely speak with Girindra’s beautiful wife, Namita, but often we simply held hands. Here she stands with her younger sister, Sobita, at right, and some village children.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

Girindra illustrated his stories in Bangla with gestures to help me understand.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

Most people in Sundarbans travel in country boats like this one, made by hand from wood and reeds.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

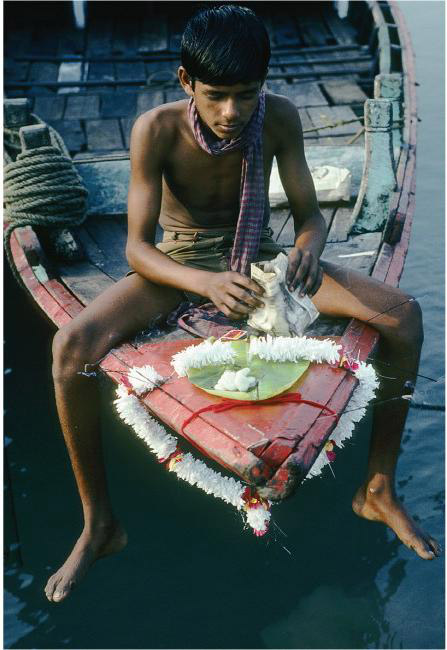

Girindra’s fourteen-year-old son, Sonaton, offers a puja, or worship service, for Mabisaka to ensure the boat’s good fortune and offer thanks for its service.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

At the Mridhas’ mud and thatch compound in Jamespur, relatives gather to repair fishing nets. In the foreground sits four-year-old Mudhushudon, nicknamed Nantu, the youngest of Girindra and Namita’s children.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

Clay images of honey gatherers adorn the diorama at the puja for Bonobibi, the forest goddess. Gathering honey is the most dangerous job in Sundarbans, but the faithful believe that prayers will induce the tiger god to spare their lives.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

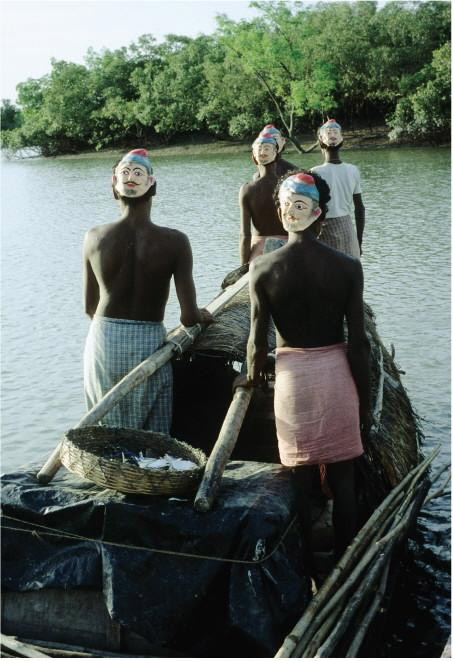

Plastic face masks worn on the back of the head were thought to confuse the tigers, who prefer to stalk and ambush prey from the back. The masks were distributed widely and were not only free but compulsory. But this is the only group of people I ever saw in Sundarbans who had the face masks on board.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

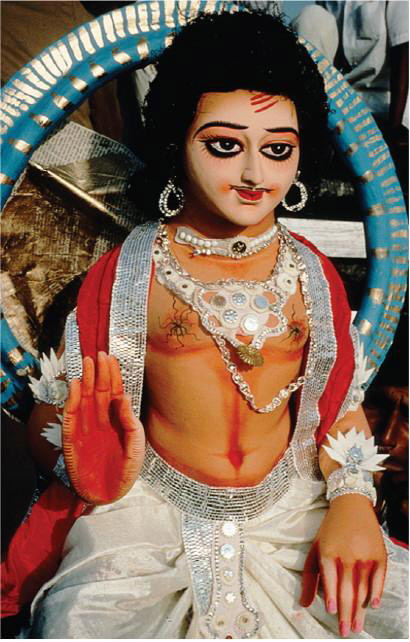

As “Lord of the South,” the richly ornamented tiger god, Daksin Ray, was said to own all the wealth of Sundarbans; to command armies of crocodiles, demons and ghosts; and to be able to enter the body of a tiger at will. Now Daksin Ray shares his land and wealth with Bonobibi, and Hindus and Muslims gather at joint shrines to worship both deities.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

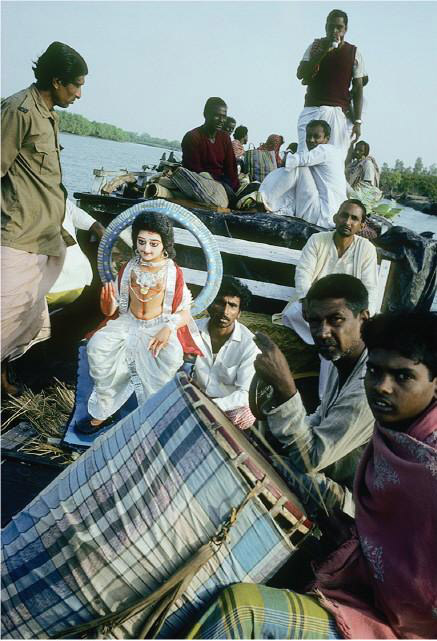

Mabisaka ferries Daksin Ray to the puja at Khahtjhuni. Musicians protect the idol on the journey with the sounds of the sacred drum and the cymbal-like kanshi. Amarendra Nath Mondal, who translated for me during the puja, is sitting on the white bench; the Brahmin priest who officiated at the puja is seated above him, in white.

ELEANOR BRIGGS

With her multiple arms, radiant smile and tiger mount, the Hindu goddess Durga embodies the fearlessness and patience of the Divine Mother.