3

‘An army in retreat, my boy.

Not very pretty, is it?’

Kokoda Trail

July to September 1942

Shot through the ankle and unable to walk, John Metson dragged himself through the jungle in the tracks of his mates. He had been offered a stretcher but, knowing it would take eight men to carry, Metson had refused. At the end of each day, his commander would ask him how he was. ‘OK, sir, 100 per cent’ was always the reply. After five days, the party finally reached a village where the wounded could remain. The others would attempt to cross the mountains and arrange rescue.1

With the naval invasion of Port Moresby stymied and the wherewithal for another invasion now beyond them, the Japanese command opted for an overland advance on Moresby. After a naval bombardment that terrified local villagers and sent them fleeing into the bush, Japanese troops landed east of Gona, on the northern Papuan coast, on the night of 21 July. The initial landing force, the Yokohama Advance Butai, was based around Lieutenant Colonel Hatsuo Tsukamoto’s I/144th Battalion, with attached engineer and artillery units. On 23 July a blustery Tsukamoto, whom one of his platoon commanders described as ‘that thundering old man,’ led his battalion inland towards Kokoda to assess the feasibility of the overland route.2

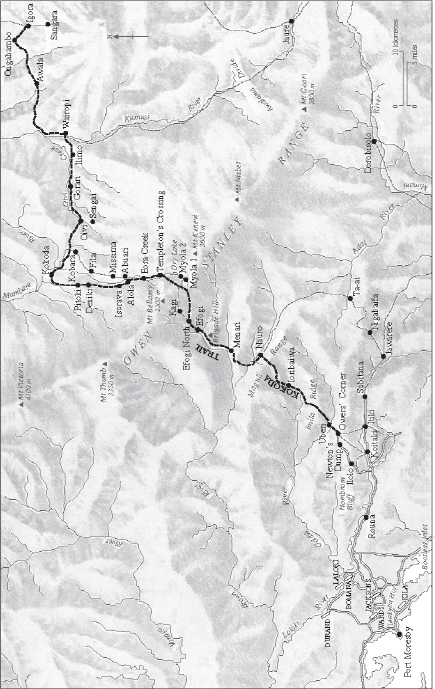

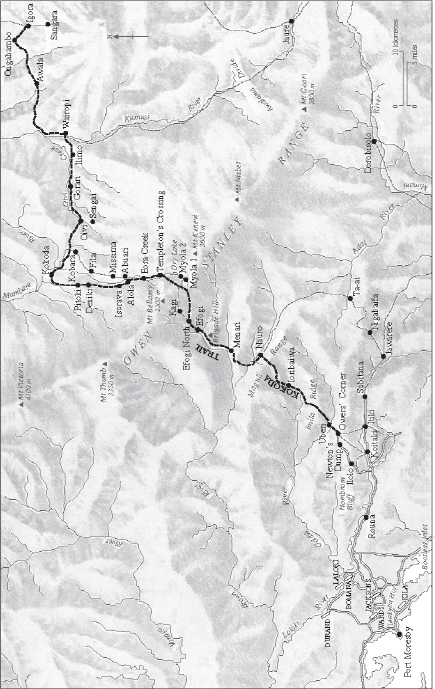

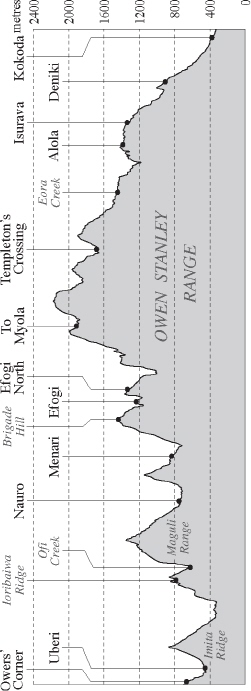

A basic road wound its way southwest from the coast at Gona and Buna to the small government station at Kokoda. Here the mountains of the Owen Stanley Range towered above the Yodda Valley, barring any movement towards the south coast except by foot over what would become known as the Kokoda Trail. This rough track meandered about 100 kilometres through the jungle-covered mountains until it emerged onto the Sogeri Plateau, above Port Moresby.

A Papuan Infantry Battalion, comprising thirty officers and 280 native men under Major Bill Watson, had been deployed between Kokoda and the coast. The 39th Battalion, a militia unit that had been raised for service in Australian territory, was also despatched from Port Moresby in early July. The militia units were generally led by AIF officers, but they were less well trained than those of the AIF, which had been raised for service worldwide but none of which was currently in New Guinea. The 39th was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Bill Owen, who as a company commander had given the Japanese a bloody nose at Rabaul. Most of the ranks were quite young, with an average age under 20. Their proud commander later called them his ‘pathetically young warriors.’ The battalion changed its obsolete Lewis guns for Brens only at the last moment, the men learning how to use them as they moved along the track.3 The first company from the 39th arrived in Kokoda on 15 July.

The troops were assisted by native carriers organised by a Yodda Valley plantation owner, Bert Kienzle. Lieutenant Kienzle would prove to be the vital cog in organising the all-important supply line along the Kokoda Trail. It was a formidable challenge: among other things, he had to recruit carriers, organise rations, build shelters and maintain the track. As he wrote in his diary, ‘Little did I know what lay in store as I tackled this task.’4

The first contact between the opposing forces took place on the afternoon of 23 July, when a PIB detachment of three officers and thirty-five men under Lieutenant John Chalk encountered Tsukamoto’s vanguard about one kilometre east of Awala village, midway between Kokoda and the north coast. An overnight reconnaissance by the Papuan Sergeant Katue, who had moved like a ghost around the enemy force, helped determine where the PIB ambush would be set. Katue swapped his uniform for a native lap lap skirt, muddied his body and hair, chewed betel nut to stain his teeth red like the locals, and behaved ‘like an idiot,’ all the while observing the Japanese moves. As Papuan soldier Ben Moide proudly noted, ‘We got a hero, we got a spy.’5 In all, Katue would spend seventy-three days behind the lines gathering intelligence, killing enemy troops, organising tribes to resist, and burning village food stocks to keep them out of Japanese hands.6

The Japanese also employed natives as reconnaissance men to warn of dangers ahead. When nine of them entered the Papuan Infantry positions, they were rounded up and kept quiet until after the ambush. Most of the PIB men were positioned on a knoll overlooking the track on the eastern side of a creek. Others, at home in the scrub, stripped off their uniforms and hid by the river bank waiting for the Japanese scouts, who were mounted on bicycles. The scouts carried two flags, a white one to signal that the way was clear and a red one for danger. The Papuans struck silently, spearing one scout after another before throwing their bodies and bicycles into the creek. When the main body entered the kunai grass clearing beside the creek, the ambush was sprung. The Papuans unleashed a hail of small-arms fire and hurled grenades at close range. Several Japanese troops fell dead, but the rest, in their first action of the campaign, responded quickly and began firing mortars onto the ambush position. It was time to leave. The PIB men dashed for the footbridge over the creek and chopped it down when the last man was across.7 Until 1981, Papua New Guineans remembered their war dead each year on Anzac Day, 25 April. Since then, 23 July has been Remembrance Day. Awala was Papua New Guinea’s Gallipoli.

Captain Sam Templeton’s company of the 39th moved east from Kokoda and formed a blocking position behind the Kumusi River near Gorari, but after a clash with the Japanese the unit pulled back to Oivi on 25 July. The Japanese had the worst of it. The lead platoon, the same one that had been ambushed at Awala, suffered eleven casualties. With Captain Arthur Dean’s company still moving along the Kokoda Trail from Port Moresby, it was decided to fly the remaining two companies of the 39th into Kokoda. However, with just two aircraft available, only a platoon could be flown across; it joined Templeton at Oivi on 26 July. Again the Japanese pressure forced the Australians back. The brave Templeton stayed behind. He was captured and later killed.8

With only eighty men to hold Kokoda, Colonel Owen dispersed them around the raised plateau where the administrative centre stood. In the early morning hours of 29 July, Tsukamoto’s men began their attack. Though Owen’s men drove them off, he himself was shot and later died. The acting medical officer, Captain Geoffrey Vernon, did what he could for Owen and other patients while enemy bullets passed through the roof above his head.9 As Ben Moide observed, ‘He don’t give a bugger.’10 Vernon was 60, and his First World War service had left him partly deaf. He had walked in unannounced from Port Moresby to Kokoda carrying his instruments and drugs in two large bandages slung across his shoulders. As Major Henry ‘Blue’ Steward later wrote, ‘The Kokoda Trail saw many quiet heroes, none more impressive than this tough old warrior.’11

With Major Watson now in command, the Australians pulled back into the mountains at Deniki. Low on supplies, the Japanese also withdrew from Kokoda. Dean’s company finally reached Deniki on 30 July, and Captain Noel Symington’s company arrived a few days later.12 Meanwhile, on 3 August Bert Kienzle had managed to locate a dry lake atop the range. ‘It presented a magnificent sight—a large patch of open country right on top of the main range of the Owen Stanleys.’ Named Myola after the wife of Kienzle’s commander, these grasslands would provide an ideal forward air-drop site, though the first drops would not take place for over a week. On 21 August Kienzle located the second and larger of the Myola dry lakes.13

After a testing six-day trek along the Kokoda Trail, Allan Cameron reached Deniki on 4 August. With Owen dead, Cameron temporarily took over command of the 39th. Having been on the receiving end at Rabaul and Salamaua, Cameron, whom the Official Historian Gavin Long described as ‘a taut, alert, hard leader,’ was now determined to carry the fight to the enemy.14 He immediately planned a three-company attack on Kokoda, with Templeton’s battered company in reserve. With the arrival of Captain Max Bidstrup’s company, total Australian strength at Deniki was thirty-six officers and 471 men, but when Cameron attacked on 8 August, only Symington’s company managed to reach Kokoda. On the left flank, Captain Arthur Dean’s company ran into most of Tsukamoto’s battalion, which was simultaneously moving on Deniki; Dean was killed in the fighting. On the right flank, Bidstrup’s men pushed through to the main track on the other side of Kokoda before withdrawing to Deniki on 10 August. An isolated Symington also returned to Deniki with his company on that day. These clashes delayed the Japanese schedule by at least a week—but that week was crucial. One of the 39th infantrymen, Jack Boland, said of the fighting around Deniki, ‘I reckon it saved our lives, because it set them back on their heels.’15

It was not until 13 August that the Japanese attacked Deniki in strength and, though they were again held off, they renewed the attack the next day and forced the 39th back to Isurava. ‘We have done our best,’ Cameron signalled Port Moresby. The Australians continued to harass the advancing Japanese. Akira Teruoka wrote, ‘We are having difficulty with enemy snipers.’16 At Isurava, the men of the 39th used their bayonets and helmets to dig rough foxholes and trenches, and on 16 August a new commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner, arrived to take over command. He found the men of the 39th in poor shape, suffering from a lack of food, sleep and shelter. Honner, who had served with distinction in the Middle East, could only tell them that they had to stand and fight. During the battalion’s time at the front, it rained nearly every day, and the men were always wet and cold at night. Honner allowed no fires, but the Japanese imposed no such restrictions. As Honner observed, ‘The fires said there were Japs all around us except to the rear.’17 Brigadier Selwyn Porter arrived at the front on 18 August to take command of what was now termed Maroubra Force. Allan Cameron was sent back to Port Moresby to report on the situation at the front—yet another arduous trek.

By 17 August the first two companies of the 53rd Battalion had arrived at Alola, just south of Isurava. Like the 39th, the 53rd was a militia battalion, but it had received little training since it reached Port Moresby. One officer who knew the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Ken Ward, described him as ‘a conscientious last-war soldier, but not a man who could inspire troops.’18 One of Ward’s men, Peter Hayman, said the men ‘spent most of the time on wharf labour and digging weapon pits in solid rock.’19 Following an exercise on 8 July, a veteran sergeant in the unit had said of the battalion: ‘75 per cent of them have no interest in the war and the other 25 per cent are fed up if having no action.’ As Gavin Long noted, the battalion ‘was made of detachments from every battalion and some other units, and naturally they did not give of their best.’20

The clashes at Kokoda had set off alarm bells in the Allied command in Australia, which rapidly dispatched Brigadier Arnold Potts’s 21st Brigade from the 7th Division. This would be the first of the AIF battalions that had returned from the Middle East to go into action in New Guinea. Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Key’s 2/14th Battalion left Australia only on 6 August. As soon as they reached Port Moresby, six days later, the men were trucked to Itiki, near the southern end of the Kokoda Trail. The 2/16th Battalion was close behind them. Another 7th Division brigade, the 18th, was sent to Milne Bay, at the eastern tip of New Guinea, where another Japanese landing was anticipated.

On 15 August, Major General Arthur ‘Tubby’ Allen, the 7th Division commander, gave Potts his orders: ‘to recapture Kokoda with a view to facilitating further ops against Buna–Gona.’ The orders also clearly set out the size of the enemy force, 1500 men already at Kokoda and another 3000 at Gona.21 Allied intelligence estimates were not always accurate, but this one was pretty close to the mark and about two thirds of these troops would move into the mountains. When the Japanese launched their main attacks at Isurava, they used four battalions, later joined by a fifth: some 3000 men in all.

The main problem here was not the quality of the intelligence but the failure of MacArthur and Blamey to draw the right conclusions from it and respond appropriately. Such a strong Japanese force needed to be delayed and held before any consideration could be given to recapturing and securing Kokoda with a relatively weaker force. Even if an airhead was established at Kokoda, there was little chance of holding it without sufficient air transports to supply it. What transports there were would then have to run the gauntlet of the Japanese fighter planes and land on an airfield that would no doubt come under sustained air attack.

A confident Potts told his officers that the brigade would carry only light equipment across the range; once Kokoda was secured, the heavy weapons would be flown in. On 15 August, the men of the 2/14th set off along the Kokoda Trail, each carrying a 30-kilogram load. The going was arduous: the track was in poor condition and the climbs and descents were steep. The ubiquitous mud made every step an effort, and the more men traversed the track, the more it deteriorated. Though the officers were given a briefing by Captain Tom Grahamslaw, who had made a number of trips across the track before the war, nothing could adequately prepare them for the reality.22 After the first day, Captain Phil Rhoden wrote, ‘not a man wasn’t exhausted.’ Of the next day’s climb, up Imita Ridge, he wrote: ‘Gradually men dropped out utterly exhausted—just couldn’t go on . . . it was physically impossible to move. Many were lying down and had been sick. Gradually everyone got up before dark.’ Further along the track, the trek up the main range to Myola ‘gave us a real taste of the track. Rain, mud almost to knees in places. Slopes almost at right angles pulling up on vines and roots, no steps.’23 Lieutenant Stan Bisset recalled, ‘The sheer physical effort was something that you couldn’t quite imagine.’24

Lieutenant Colonel Albert Caro’s 2/16th Battalion followed the 2/14th up the track on 17 August. The peppery Caro had distinguished himself as a company commander with the 2/16th in Syria, where Arnold Potts had commanded the battalion.25 The 45-year-old Potts, who had served throughout the First World War, now shared the toil of his men in this new war, so different from any that had preceded it. His main concern was that, despite Kienzle’s sterling efforts, there was a critical lack of supplies along the track. Potts reached Alola on 22 August and took over command of Maroubra Force from Porter the following day, becoming the force’s third commander in a week. In his first action as a brigade commander, Potts now also commanded two militia battalions. However, owing to the shortage of supplies, the two advance battalions of 21st Brigade were halted at Myola while the third, the 2/27th, remained in Port Moresby. The supplies they had expected to find at Myola were just not there: Potts had his hands tied from the start. Yet his orders stood—recapture Kokoda.

The senior supply officer at Myola did not even know that 21st Brigade was to be supplied until the first troops arrived. The supplies that were delivered were free-dropped from the transports, and most of the bundles were lost. Even when parachutes were used, only about half of the supplies were recovered.26 Rhoden wrote how the battalion had to be deployed a company at a time, ‘because we couldn’t supply so many at a time. We had to be committed bit by bit.’27 Meanwhile, the loss or damage of the five available transport aircraft during an air raid on Seven Mile strip on 17 August stopped all air drops for five days.28 And as the supply problems grew, so did the threat from the enemy on the ground.

From 19 to 21 August, the main body of Major General Horii’s Nankai Shitai, or South Seas Detached Force, landed at Buna. The force comprised the remaining two battalions of the 144th Regiment and two battalions from Colonel Kiyomi Yazawa’s 41st Regiment, seasoned veterans of the Malayan campaign. Significant artillery and support units were also landed, the latter including 875 native carriers from Rabaul and 400 horses. Lieutenant Colonel Kuwada’s III/144th Battalion, the butchers from Tol Plantation, would join up with Tsukamoto’s battalion in front of Isurava, while Major Tadashi Horie’s II/144th Battalion would advance along the east side of the Eora Creek valley via Missima to Abuari. The men of Horie’s battalion did not lack ambition: some of them anticipated capturing Port Moresby within three days of leaving Kokoda.29

At 1600 on 26 August, just after the first units of the 2/14th Battalion had reached Alola, the Japanese attacked the 39th at Isurava with two battalions, Tsukamoto’s I/144th and Kuwada’s III/144th. Tsukamoto’s men broke into Honner’s left flank from the high ground, but the Australians counterattacked swiftly and restored the position. The fighting went on throughout the night. On this flank, the Australians had the clear ground of an old native garden in front of their positions, which they had dug out with their steel helmets and empty bully-beef cans. Despite the desperate odds, the company on the left held until only thirteen men remained.30

On the morning of 27 August, Potts ordered the 53rd Battalion, now deployed across the other side of Eora Creek at Abuari, to retake Missima. Moving up to check on the progress of the attack, Lieutenant Colonel Ward and two other men were killed in an ambush. Major Charles Hawkins took over the battalion. With Missima still in enemy hands, a concerned Potts pulled the 53rd back to defend Abuari and thus protect Alola and Isurava from being outflanked. However, he did not move to protect Abuari from the same fate. Abuari was well down the side of the steep Eora Creek valley, and the infantrymen of Horie’s II/144th pushed forward relentlessly to outflank the village from the higher ground. On 25 August, they had ‘slashed ahead through the jungle all night long’ before traversing steep cliffs the next day and then marching all night through the rain. Before dawn on the morning of 29 August, the Japanese attacked Abuari from the dominant high ground and captured the village.31

When the 2/16th Battalion reached Alola at around midday on 28 August, two companies under Captain Frank Sublet were immediately moved across towards Abuari. The next day they faced the same problems as the 53rd because the Japanese held the higher ground. At least two Juki machine guns had been emplaced in unassailable positions above the waterfall covering the track up to Abuari. As the Australians tried to reach the guns from the left flank, a man was hit. To stop himself from falling down the cliff face, he grabbed at a comrade, who did the same to a third man. All three went over.32

At Isurava, most of the 2/14th had taken over the 39th Battalion’s positions by 28 August. When the Japanese attack began, Captain Claude Nye’s and Captain Rod Cameron’s companies were forward, with Captain Sydney ‘Ben’ Buckler’s company in reserve behind them. Buckler wrote, ‘The storm broke in full fury . . . Mortar bombs and mountain gun shells burst in the tree tops or crashed through to the ground, HMGs cut out their own lanes of fire.’33 The Japanese assault split Cameron’s company, and one of Buckler’s platoons was sent to take back the position. The Japanese continued probing throughout the night.

The following day, 29 August, the Japanese again pressed hard at Isurava. Rhoden wrote, ‘Japs were moving around the flank, striking here and then there. Our first experience of their yelling, like a final football match. Yelled so much some of our chaps would yell “come on Collingwood!”’34 Stewart Clarke, who was in Buckler’s company, simply called it, ‘Hell on earth amongst the clouds in the mountains.’35 After the loss of Lieutenant Bill Cox, Corporal Lindsay ‘Teddy’ Bear took charge of 9 Platoon and rallied the men. He later said, ‘My Bren gun at Isurava was so hot I couldn’t even pick it up.’ There were only two barrels available for the gun and no water to cool them; the men were so dehydrated they couldn’t even piss on the overheated barrel. But it had to be changed, and Bear burned his knuckles doing it. He later said that ‘the whole of the action at the back got so hot you could hardly hold that Bren gun.’ Bear was eventually stitched up by a Japanese light machine gun, shot in the foot, the knee, the thigh and the shoulder. Unable to stand, he handed the Bren to his loader, Bruce Kingsbury: ‘Righto, Bruce, it’s over to you.’36 Kingsbury reloaded the gun, lifted it up and, firing the red-hot weapon from the hip, strode forward to cut down the attacking Japanese. The position was recaptured, but Kingsbury was shot dead by a sniper. He was later awarded the Victoria Cross.

On the left flank, Nye’s company faced continued assaults as the infantry of Kuwada’s battalion pushed for the high ground. Kuwada’s troops found it much tougher closing with armed Australian infantrymen than with the defenceless bound prisoners at Tol Plantation on New Britain. Two of Nye’s platoon commanders were killed during the fierce battle. One of them, Lieutenant Harold ‘Butch’ Bisset, was brought back by his men and died with his brother Stan by his side. The increased pressure forced the 2/14th to withdraw. It was none too soon as Major Mitsuo Koiwai’s II/41st Battalion, the first unit of Yazawa’s regiment, was deployed. Like Horie’s battalion on the other side of the valley, Koiwai’s unit had moved well out to the flank aiming to cut the Kokoda Trail behind the main Australian positions.

Charlie McCallum, a Bren gun in one hand and a Tommy gun in the other, let the enemy have it, staving off the Japanese as his comrades pulled back. Warrant Officer Les Tipton, the 2/14th regimental sergeant major, who had refused a commission five times, did as much as any to hold the line. Captain Geoff Lyon described him as ‘Tough, profane, with the face of a pugilist and a heart of gold . . . looked after the troops like a mother.’37 It was ugly work in more ways than one. Ben Moide observed, ‘That place Isurava it’s a dirty place . . . rain, rain, rain it can’t bloody stop. The Australians that fought there they look all black, not white.’38

With the Japanese now committing four battalions of infantry to the battle, three of them fresh and with another in reserve, Potts had to reconsider his position. Not that the enemy strength should have surprised him given the intelligence estimates in his original orders. Still denied his third AIF battalion and adequate supply, Potts withdrew the heavily outnumbered 2/14th back to the rest-house area, halfway to Alola. He also sent the 53rd Battalion back to Myola and beyond, something his orders allowed but still an extraordinary decision given that his force was already outnumbered. As the A Company commander, Captain Des O’Dell, observed, ‘This was a complete surprise to all 53 Bn officers.’ Though ill-equipped and poorly trained, the companies were still under firm command, and the men, having made the arduous trek in, were ready to fight.39 Potts would have sent the 39th Battalion back with the 53rd, but its companies were still engaged in the fighting. It seemed that Potts’ disdain for the militia troops was as great as his disdain for the Japanese. ‘Desire return 39 and 53 Bn to Moresby,’ Potts signalled Allen at the height of the battle on 31 August.40

In fact, Allen and Potts had already stitched up the two militia battalions when Potts’ orders had been written. These stated that both battalions could be used ‘as determined’ by Potts.41 The poisonous relationship between some of the AIF officers and the militia men, or ‘chockos’ (chocolate soldiers) as they were derogatorily termed, persisted until the end of the war. Of course the militia men had less training and experience than the AIF troops, but all were Australians, all were fighting for their country, and all would be needed to win that fight.

Since the 39th Battalion had fought so admirably, thoroughly disproving Allen’s and Potts’ blinkered assessment, the men of the 53rd Battalion now became the fall guys. ‘They cannot be relied on,’ Potts signalled Allen on the morning of 28 August.42 When a company of the 53rd was sent to help the two 2/16th Battalion companies at Abuari on 29 August, the brigade diary recorded that they ‘broke and scattered.’43 Lieutenant General Sydney Rowell, the commander of I Australian Corps, embellished the record in his later report, stating that a company of the 53rd had thrown away their arms and refused to fight.44 Blame it all on the militia troops was the order of the day. The 2/16th war diary tells the true story. On 29 August, D Company from the 53rd was sent to outflank the Japanese above Abuari. As Frank Sublet was informed at 1200 on 30 August, that task was beyond them. ‘Progress above waterfall impossible,’ the message said. ‘Dug in where we were.’45 Hardly throwing away arms and refusing to fight.

Sublet’s opinion holds considerable weight here, as he commanded the two 2/16th companies at Abuari, both of which were also unable to break the Japanese hold on the high ground. Writing after the war, Sublet commended some of the 53rd’s patrol actions and noted that ‘when Potts peremptorily sent the battalion out of battle, its morale and commitment fell.’46 Stan Bisset saw the result of this when, near Alola, he came across one leaderless group from the 53rd who would not retire from the battlefield. ‘In the end I had to pull my revolver out and said get moving, we’ve got to move, we’ve got the fellows coming back, withdrawing into this position.’47 They weren’t there because they didn’t want to fight; they were there because they did.

Meanwhile, the Japanese companies kept pressing. They were now also firing machine guns across the valley from Abuari into Alola village. Sublet’s two companies held the track down to Eora Creek, but after two unsuccessful attempts to flank the enemy positions above the waterfall and a third attack directly up the spur, Sublet was ordered to withdraw after midnight on 30 August. Some men had reached the positions above the waterfall earlier in the day, only to discover that there were more Japanese higher up.48 After one of 11 Platoon’s section leaders, Corporal Michael Clarke, was killed, George Maidment gathered Clarke’s grenades and attacked the machinegun posts above the waterfall. Though hit in the chest, he kept on and managed to destroy some of the positions. He then went back, grabbed Clarke’s Tommy gun, and continued fighting. Later Maidment made it back to the RAP, where he collapsed and was carried out on a stretcher. After being seen at a dressing station, he went missing; no trace of him was ever found. Though Maidment’s company, battalion, brigade and divisional commanders all recommended that he be awarded the Victoria Cross a lesser award was made.49

Unsure of the situation at Alola, Sublet’s men made their way up Eora Creek in the dark, each man holding the bayonet scabbard of the man in front and rubbing fluorescent fungi onto his pack so he could be seen in the dark.50 Up on the main track, the 2/14th also raced to get back before being outflanked. Rhoden wrote, ‘Men were still in good heart as they fell back over slippery stones, carrying absurd weights, carrying back the wounded.’51 Lieutenant Colonel Key and four others were cut off and then captured by a Private Doi on 10 September. Key was taken to Kokoda for interrogation and presumably murdered.52

The Japanese also took severe losses. One noted that ‘the fire from enemy rifles and guns was so intense that collection of our dead and wounded could not immediately be accomplished.’ After collecting casualties all day from the battlefield, one of the medical men wrote in his diary on the evening of 29 August: ‘Worked desperately as nurse.’ One of Tsukamoto’s men simply observed: ‘Section was completely annihilated.’ The scale of loss can be gauged by Tsukamoto’s 1 Company, now below half strength and with its third company commander. The previous incumbent, Lieutenant Seizo Hatanaka, had been killed at Isurava, no doubt dying a happy man: he had earlier told his men, ‘In death there is life. In life there is no life.’ The latest commander, Lieutenant Kogoro Hirano, and his successor, Lieutenant Kaji, would also fall before the end of the campaign. When Akira Teruoka went through the area three days later, he wrote, ‘There must have been a great battle here because the dead enemy bodies are scattered all over.’53 Yazawa’s 41st Regiment took up the advance and pressed hard on the heels of the Australians.

Potts pulled his force back to Eora Creek, where Lieutenant Brett Langridge’s company held fast on the ridge above the village. This rearguard took a considerable toll on the closely following Japanese, buying time to get the many wounded out. Three hundred carriers had to be sent forward from Myola to handle the thirty-odd stretcher cases. Aware of the shortage of carriers, many men who should have been on stretchers chose to struggle back on their own. Teddy Bear, with a bullet in each ankle and another in one of his knees, was one of them. He could only shuffle along, supported by his one good leg and a wooden pole. ‘Russ’ Fairbairn, who had a bullet lodged near his spine, joined him. Fairbairn kept saying, ‘Come on, Linds. Come on, Ted.’ Bear remembered, ‘Somehow he’d get me going and he would stand on the downside if I was slipping or he would stand on the upside if I couldn’t climb to stop me falling back.’54 Another casualty hobbled along the track with one leg missing below the knee. When offered a stretcher party he retorted, ‘Get them for some other poor bastard! There are plenty worse off than me.’55

Ben Buckler took charge of Lieutenant ‘Mocca’ Treacy’s wounded, as well as forty-two other men, and moved them down into the thick jungle of the Eora Creek ravine. John Metson had been shot in the ankle and was unable to walk but, knowing that a stretcher would take eight men to handle, he refused to be carried and crawled along behind Buckler’s party. Buckler sent Treacy with two men to get help from Myola, but it took them a week to get there, by which time the Australians had pulled out. Treacy then headed southeast, reaching Dorobisolo on 22 September.

Buckler waited five days for Treacy before heading down Eora Creek to the Yodda Valley, keeping well to the east of the Kokoda Trail. After ten days, his group reached the village of Sengai, southeast of Kokoda, where it was decided to leave the wounded. Tom Fletcher volunteered to stay with the five wounded and two fever-ridden men while Buckler led the rest back to Allied lines. After parading in front of the wounded, Buckler’s party of two officers and thirty-seven men departed, following the Kumusi River upstream before meeting American troops near Jaure on 28 September. Supplied with food, they then climbed over the Owen Stanley Range to Dorobisolo, arriving two days later. ‘Bluey’ King, who had been wounded at Isurava, died here. After two more days of walking, Buckler’s party traversed the last leg of its journey down the Kemp Welsh River to Rigo using ten crude river rafts. They arrived on 3 October. Meanwhile, Fletcher’s small party at Sengai was betrayed to the Japanese; all were callously murdered.

Damien Parer, the war photographer, had made the trek along the track as far as Eora Creek accompanied by the journalists Chester Wilmot and Osmar White. Anxious to preserve the film in his backpack, Parer had flattened his hat and pushed it down between his back and the pack to stop his sweat soaking through as he climbed. The descents were as tough as the ascents. Wilmot noted that ‘thousands of military boots have broken the roots away and there is little or nothing to stop you slipping.’56 White watched Parer, who was clearly struggling. ‘Clipped by a sharp dose of fever—his first acute attack—pale, streaming profusely with sweat, and at the same time shivering violently, he refused stubbornly to stop.’57 The three men reached Eora Creek just as the front at Isurava was breaking down, and they were soon ordered out. The casualty clearing station was a two-room grass hut; the operating table was a stretcher with a blanket draped over it; a biscuit tin over a fire served as the steriliser. ‘There are no refinements about war in the New Guinea mountains,’ Wilmot observed.58 Parer struggled back, abandoning his camera gear as he went but not the precious film. ‘An army in retreat, my boy,’ he said to White. ‘Not very pretty, is it?’59 Parer would later film native bearers carrying the wounded to the rear, documenting their astonishing fortitude, care and devotion. It took 400 bearers seven days to get the forty-four stretcher cases out. Bert Kienzle wrote: ‘The carriers had been called on to stand up to superhuman efforts.’60

The Japanese also had their war correspondents. One of them, Seizo Okada, accompanied Horii’s advance across the daunting main range. ‘We felt as if we were treading on some living animal,’ he wrote. ‘We were walled in by enormous mountains . . . All the troops now showed unmistakable signs of weakness and exhaustion. But they marched desperately on and on.’61

Meanwhile, the 21st Brigade’s third battalion, Lieutenant Colonel Geoff Cooper’s 2/27th, had left Port Moresby. The battalion moved up the track in stages, one company each day. The initial steep drop from Owers’ Corner down to the Goldie River had men slipping and sliding until, at the bottom, they were knee deep in mud. Sergeant Clive Edwards wrote, ‘It became a shocking and heartbreaking trip . . . I arrived at Uberi a filthy and a tired man.’ Next day, Edwards and his fellow soldiers climbed the ‘golden stairs’—sawn-log steps set into the near-vertical slope—to Imita Ridge, then down again before the next haul up Ioribaiwa Ridge. He wrote, ‘At this stage the platoon split up and became a medley of individuals fighting their way grimly up a terrific climb. It was a terrible day’s stage.’ Day Three took in the climb up the Maguli Range and then down to Nauro. Edwards continued, ‘We began to pass wounded and evacuated personnel from the mob in front.’62 Frank McLean remarked that ‘when they came through us they were the most dishevelled and just raggedy crowd you’ve ever seen in your life.’63

Next morning, the supply planes began dropping stores on Nauro. In the process, they killed one man and injured another five. That day, Edwards and his comrades walked across the Brown River on a fallen-log bridge, reached Menari, crossed Brigade Hill and then headed for Efogi. ‘We hit the downhill stretch and it was as slippery as glass and at the end, as rough as the devil,’ Edwards wrote. On the morning of 5 September, his company fed well and returned to Brigade Hill. Next day, Edwards ‘heard the first shots of this Jap war when Mr. Bells’ platoon of A Coy clashed with the Jap on the other side of U’Fogi [sic].’64

Potts’ strategy was now one of holding rearguard positions to cover the withdrawal and, he hoped, making a stand on the southern side of the range. As his troops moved back through Myola, they destroyed what food and ammunition they couldn’t carry. Still dogged by supply difficulties, Potts took his brigade back to the high ground above Efogi and deployed his three battalions to hold the Kokoda Trail and stop the Japanese advance. Cooper’s fresh battalion would hold Mission Ridge, a sharp spur leading up the range from a Seventh Day Adventist mission station, while the 2/14th took up positions astride the ridge behind Cooper. Further back, Potts spread out the 2/16th along the ridgeline of Brigade Hill. General Sydney Rowell told Major General George Vasey, the deputy chief of staff and Blamey’s right-hand man, that he had ordered Potts to ‘yield no, repeat no more ground.’65

Meanwhile, on 28 August, with the fighting at Guadalcanal making increasing demands on Japanese resources, Horii had been ordered to advance only to the south side of the Owen Stanleys and then mass the main strength of his force on the north side of the range. As his troops descended the main range to Kagi, Horii could see that the Owen Stanleys stretched on towards Port Moresby. He had more ridges to cross before he reached the south side of the range: Efogi Ridge was the first.66

On 6 September, Potts gave a vigorous address to the newly arrived 2/27th troops, telling them that ‘every man must hold out as long as ammunition lasted.’ Later that day, the battalion moved higher up the ridge, where Captain Charlie Sims’ company dug positions using their bayonets and helmets. Gavin Long later characterised Sims as ‘boyish, high-principled, intrepid.’67 The coming clash would test him. On the night of 6–7 September, these forward troops of the 2/27th could see the Japanese columns move down Kagi Ridge from the main range, using torches made from captured insulation wire to light their way. Frustratingly, the Australians had no weapons with enough range to fire on them. Looking down into the valley, Alec ‘Slim’ Little watched the Japanese ‘with their lanterns moving up in the night.’68

The first assaults on Mission Ridge came before dawn on 8 September, hitting Sims’ company on the right flank. Further back, Edwards noted, ‘At about 4 a.m. hell broke loose and the Japs attacked A Coy’s front. We had no attacks on our particular front but there was a terrific amount of muck whizzing over our heads. Well, the racket continued with slight lulls, all the morning.’69 The attack was supported by mountain guns. The men felt the shock wave of the shells flying across their positions even before they heard the guns’ fire. A man in the forward weapon pit was hit in the first barrage and staggered back, holding his guts in with his hands. Bob Johns, a platoon sergeant, helped a stretcher bearer try to stem the bleeding and seal the gaping wound. As the sun set, another wave of Japanese attacked, led by a sword-wielding officer who was felled by a Tommy-gun burst. The noise roused the wounded man, who cried out again, then closed his eyes for the last time. His final words lingered: ‘I don’t want to die.’70 The 2/27th used up their entire ammunition reserve in staving off the assault. Frank McLean noted that ‘it became almost a grenade war . . . we were priming them in long lines.’71 Sims’s men used 1200 grenades that day; by its end his company was down to sixty-seven men from over 100.72

While the Australians were reflecting on their success, the Japanese had already made the decisive move of the battle, a flanking move by about 160 troops from 5 and 6 Company of Horie’s II/144th Battalion, aided by engineers. The force had left Efogi on the previous day and moved undetected around to the west of the Australian position despite ‘steep hills and entangled vines.’ Early on the morning of 8 September, they advanced onto the ridge among the strung-out 2/16th positions further back on Brigade Hill, cutting off almost the entire 21st Brigade.73 It was a stunning stroke: for the second time, Horie’s battalion had totally outmanoeuvred the Australians. Even more extraordinary was that the Japanese force was uninterrupted for hours while it dug in across the track. Potts had not deployed suitable outposts or patrols to cover his vulnerable western flank; he had not even put sentries on the main track behind the forward battalions. The 2/14th and 2/16th Battalions, in behind the 2/27th, were positioned to cover only shallow flanking moves. Such a move from the west would have to be made through precipitous terrain, but further back at Brigade Hill the way was passable. Yet Potts had deployed no troops here at all. Only his brigade headquarters and Captain Brett Langridge’s 2/16th company remained on the Menari side of the incursion. At 1100 the Japanese force, about two companies strong, attacked Potts’ headquarters with grenade dischargers and light machine guns in support, and got to within 30 metres of the post. The attacks went on until 1400, but the Australians held. As Captain Geoff Lyon, the divisional liaison officer, related, ‘Everyone downed tools and began to fight.’74

To break the Japanese position astride the track, three companies attacked back from the pocket: Nye’s company of the 2/14th, and the 2/16th companies of Captain George Wright and Captain Doug Goldsmith. A third 2/16th company, under Captain Sublet, would support Wright’s assault straight down the main track. By the time the attack began at 1450, the defenders had had at least nine hours to prepare for it. On the left flank, Lieutenant Bill Grayden watched as the forward troops were deployed in an extended line, bayonets fixed to their rifles, waiting in the steady rain with their groundsheets around their shoulders. A 3-inch mortar fired over their heads, the dull thuds echoing back along the ridge. As the support fire ceased, the Australians moved forward at a steady walking pace, shouting and firing, trying to frighten the enemy troops. Grayden recalled how ‘the first limited exchange of shots erupted into an intense fusilade from both the Japanese and attacking troops’. Though forced back into a narrow enclave, the Japanese troops held the main attack along the vital track. Some of Nye’s men made it through, but Nye and sixteen others were killed. On the left, Sublet also got some men through, Grayden among them. But the main force got no closer than 100 metres. Listening to the attack heading his way, Potts remarked that the intensity of the fire was far greater than he had heard at Gallipoli. Another said, ‘It was quite some fight, it was furious.’75

As a last resort, Potts told Langridge to attack with his company from the brigade headquarters side to open the track. Langridge led one of his platoons forward on one side of the track, with Grayden and the breakthrough remnants on the other. But the attackers had to pass across relatively open ground before they entered the rainforest, and the Japanese cut them down. The brave Langridge was killed at the head of his men, only a few paces from the start line. Lieutenant Henry ‘Blue’ Lambert, one of Langridge’s platoon commanders, also fell, along with twenty other men.76 Captain ‘David’ Kayler-Thomson, Langridge’s 2IC, took over the company remnants and was told, ‘The brigadier wants you to try again.’ He replied, ‘I haven’t enough, but I’ll try.’ Turning to Alan Haddy, the company sergeant major, he said, ‘Well, this looks like good night nurse, good morning Jesus, Alan.’ ‘Well, you can’t live forever, boss,’ the irrepressible Haddy replied.77 Then reality hit Potts and he cancelled the attack; he was only killing off what few men his brigade had left.

Including the service troops at Menari, Potts had only seventy men under his command between the Japanese and Port Moresby. He pulled his headquarters out early that night, and the men moved in single file down the track to Menari. The rearguard numbered forty men, fresh troops under the 2/14th’s Captain Bill Russell who had only arrived that day.78 That same day, 200 soldiers from the 53rd Battalion whom Potts had sent back to Port Moresby had also passed through Menari.79 The 39th Battalion had left Menari only two days earlier; Damien Parer had photographed them proudly forming up in their ranks. Properly used to guard the unpatrolled gap behind 21st Brigade on Brigade Hill, these men could have contested any Japanese move up onto the ridge or at the very least given early warning. As it was, the Japanese had plenty of time to set up a strong defence. Potts’ scorn for the militia troops had come back to bite him.

Cut off from the main track, most of the men from 21st Brigade moved south through the jungle, attempting to rejoin the Kokoda Trail further back towards Menari and Nauro. Clive Edwards wrote, ‘It was pitiful—the rain was coming down, and there was a long string of dog tired men straining the last nerve to get wounded men out and yet save their own lives too. Bewilderment at the turn of events showed on every face.’80 Edwards’ company had not fired a single shot in anger and was now in retreat. Back on Brigade Hill, Captain Mert Lee’s company held a rearguard position for the 2/27th, buying vital time for the withdrawal. At one stage Lee led a brazen counterattack to gain even more time. Lieutenant Jack Reddin called it ‘a very savage little rearguard action.’81

The remnants of the 2/14th and 2/16th, about 300 men under Colonel Caro, made it back to Menari the next day, 9 September. Sheer willpower got them there. Phil Rhoden, a former football team captain, gave a remarkable speech to the men. Stan Bisset observed its effect: ‘They could see themselves picking their heads up and they forgot about their weariness.’ Bisset was one of the first to reach the top of the climb into Menari. Major Albert Moore from the Salvation Army was waiting for the weary troops with coffee, chocolates and cigarettes. Moore dispensed 160 litres of coffee that day. Bisset never forgot the expressions on the men’s faces when they were handed a block of chocolate or a pack of cigarettes and he knew they could now keep going. Menari was not defensible, and the troops had to keep moving. Bisset recalled, ‘We waited as long as we could for the 2/27th but they were handicapped.’82

Leaving last, and carrying the brigade’s casualties out with them, the 2/27th had made slow progress. Carrying a single stretcher over such steep terrain took eight men. ‘We bivouacked in death gully,’ Sims wrote, ‘alive with screaming cicadas and lit with phosphorous of decaying trees.’ Next day, 9 September, it took five hours to get the stretchers across a steep gully. Sims’ company went on ahead. Strung out in single file, they climbed the steep slope below Menari. They passed empty boxes with Japanese markings on them—a worrying sign. At 1530, firing broke out from higher up; the Japanese had reached Menari ten minutes ahead of Sims. Low on ammunition and knowing he could attack up the spur with only two men at a time, Sims turned his company around.83 Cooper’s battalion was now cut off from the Kokoda Trail and would do well just to survive. The outlook was grimmest for the wounded.

Johnny Burns was a 2/27th signaller who had picked up one of the wounded 2/16th men as he left Brigade Hill. The battalion continued to carry the stretchers and tend the injured men until the morning of 19 September, when Captain Harry Katekar told Burns, ‘The CO wants to know whether you will take charge of the stretchers.’ Burns replied that he was not a medical man and that someone more senior should take charge, but in the end he agreed. Burns and Alf Zanker stayed behind with the seven stretchers and the nine walking wounded. At times they used their shirts and singlets to dress the wounds. They also had to wash the men, get them water and deal with those who had dysentery and diarrhoea. When the mist came up the valley, they would light a fire and cook some yams for the men. One soldier’s leg had to be amputated, though no one had ever performed such an operation. The man died the next day, and Burns and Zanker dug a grave for him using their helmets and machetes. They buried another man two days later. When some natives brought them food, Burns gave one of them his last ten shillings to take one of the walking wounded out to Itiki, a trek that took ten days. For those who remained with the heat, the flies, the downpours and the hunger, there was only a growing despair. On 2 October, thinking the Japanese were coming, Burns and Zanker prepared to defend their position while those who could crawled off to hide in the scrub. It was a 2/27th patrol, bringing in Captain Robert Wilkinson from the 2/4th Field Ambulance. Five days later, the party reached safety.84

On 22 September, fourteen days after leaving Brigade Hill, Clive Edwards and his mates reached the Australian lines at Jawarere. He wrote, ‘I can’t possibly describe fully the hopes and fears, achievements and disappointments, the sheer determination and will to survive which was all that kept us going during some of the harder stages . . . Each night I used to think of the mob at home and pray for them, and myself.’85 One of the lads who had been wounded in the buttocks by a grenade at Brigade Hill walked all the way out to the Itiki Valley. He couldn’t lie on his back and God only knew what pain he endured, but there was not a murmur from him.86

Les Thredgold, his young brother Col and two others set out to find food and a way back. They followed a ridge to a cliff, then Les climbed down the root of a tree and onto a ledge. Another chap followed, but as the third one came down the root started to give way and he nearly knocked the other two over the cliff face. As Col descended, the root came out of the ground under his weight, but somehow the four of them managed to stay on the ledge. Les later said, ‘I don’t know till this day how we survived.’ Stranded on the ledge, they spied a bit of a slant in the rock, which they followed down to the bottom of the cliff. Reaching the head of the Goldie River, they followed it, since they were too weak to climb out of the valley. They found an abandoned village, but as they left Les saw that ‘from every stone there was a gun pointing at us. I thought it was a Jap ambush.’ Then someone yelled out, ‘Hold your fire, they’re Aussies.’ Back in the Australian lines, Les had his clothes cut off, was given a drink of Bovril, and lay down to sleep. He woke at first light in a daze, heard ‘Blue Moon’ playing on a wind-up gramophone and thought he had gone to heaven.87 He had already been through hell.

Potts was still getting orders to hold a firm base and advance to Kokoda. He asked Geoff Lyon, ‘What is a firm base. I haven’t got one here—I think they’d better send one up.’88 He had lost his firm base, and most of his brigade with it. Meanwhile, Rowell gave Vasey the bad news that ‘Potts is at this hour in serious trouble between Efogi and Menari as a result neglect penetration.’ Vasey stated the obvious in his reply: ‘It does appear that Potts action did not take account of the well-known Japanese tactics.’89 The neglectful Potts should certainly have been aware of such tactics; his troops had been outflanked twice at Isurava. Brigadier Porter was sent up to replace Potts, who was recalled to Moresby and relieved of his command the following month.

On the afternoon of 10 September, Porter took over command of Maroubra Force near Nauro and decided that the next suitable defensive position was back at Ioribaiwa Ridge. Caro’s composite battalion began to withdraw the next day, passing through the newly arrived 3rd Battalion, which had moved up from Port Moresby. The well-equipped 3rd—each section had two Tommy guns and a Bren gun—had begun the move on 5 September. Though the men had trained for a number of months around Moresby, they had to learn the real intricacies of jungle warfare on the job.90 It was a tough classroom, as the battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Albert Paul, discovered only two hours into the trek to Ioribaiwa: exhausted, he dropped out. With the 53rd Battalion out of the battle, Allan Cameron was given command of the 3rd, his third battalion command in less than a month. Having now decided that Ioribaiwa Ridge would be difficult to defend, Porter proposed to hold Imita Ridge, a superior defensive position. However, he was told to stick to the original plan and hold Ioribaiwa, a poorer option but further from Moresby. The Australian commanders’ nerves were jangling. Cameron had the 3rd Battalion back on Ioribaiwa Ridge late on 11 September.91

On 14 September, the 2/31st and 2/33rd Battalions from Brigadier Ken Eather’s 25th Brigade also reached Ioribaiwa Ridge, with the 2/25th Battalion in reserve behind them. Eather took over operational control of what was now the ‘must hold’ position in front of Moresby. With four fresh battalions and Caro’s remnants, Eather had more than enough strength to hold a badly weakened Japanese force that was further handicapped by an ever-lengthening supply line.

An ambush position was set up at the former supply dump at Ofi Creek, below Ioribaiwa Ridge, where the Australians knew the enemy troops would gather. Lieutenant Ron Christian’s platoon from the 2/16th sprung the trap in the late afternoon. With most of the enemy troops in the river bed, the Australians opened fire from positions overlooking the crossing. Twenty or thirty enemy soldiers fell before Christian’s ambush party headed back up Ioribaiwa Ridge. A smaller enemy patrol was ambushed further up the hill.92 The Japanese responded by shelling the ridge with mountain guns. They would fire eight to ten rounds at a time, usually at meal times. The Australians thought they would be safe dug in along the crest, but the shells were directed into the trees above them and the lethal fragments rained down on the men below.93

Eather’s inclination was to attack immediately, and he sent the 2/31st and 2/33rd off on intricate and ill-considered flank movements. At 1500 on 14 September, three companies of the 2/31st made an attack on the left flank, but they were stymied by the terrain and forced to withdraw in the dark. The next day, the Japanese troops made their own attack, better planned and better executed: they made the terrain work for, not against them.

After a heavy mountain-gun barrage, the initial push came up the main track but was foiled by the staunch Australian defence. However this was only a holding attack; the key move again came from the flank, just as it had at Isurava and Brigade Hill. At 1310 the Japanese infiltrated into some unguarded 3rd Battalion positions where the men from 17 Platoon were busy digging in or eating, apparently without sentries posted. About twenty Japanese soldiers got past them onto a dominant knoll, a simple operation, done with minimal force but with complete surprise.94 Lieutenant ‘Bert’ Madigan of the 2/16th put in a counterattack but was wounded by a mountain gun shell as the attack stalled. From this high position on the eastern flank, the Japanese now controlled the ridge and Ioribaiwa village below.

General Allen told Eather to hold for as long as possible. But as David Kayler-Thomson took his depleted 2/16th company back from the forward positions he was amazed to see the fresh 25th Brigade troops also retiring. Eather had made his decision before midday on 16 September and within 24 hours his brigade was back on Imita Ridge.95 ‘Ioribaiwa was a hopeless bloody thing while Imita Ridge, which was just behind it, was a much more pronounced feature,’ Eather observed 50 years later. ‘There wasn’t much between them. Just a few yards.’96 It was actually nearly six kilometres but that was six kilometres closer to Moresby. From an operational viewpoint it may have been the correct decision but politically it was dynamite.

Another fresh battalion, the 2/1st Pioneers was diverted from working as glorified labourers at the gravel quarry and moved up to augment the Australian force on Imita Ridge. The pioneers were pleased to leave the quarry where, as one told Gavin Long, ‘we used to pray for Tojo to come over so that we could have a spell.’97 Three 25-pounder guns of the 14th Field Regiment supported the infantry from Owers’ Corner. Operationally, the Australian commanders had got things right, stiffening the defence when it had to be done, and with the short supply line from Port Moresby, when it could readily be done. The Japanese advance had come far enough. Eather had no intention of again being caught unawares and his brigade carried out extensive patrolling of the area between Ioribaiwa and Imita Ridges looking for the next Japanese move. But the Japanese did not come.