Buna

November to December 1942

The humidity hung heavily over Duropa Plantation, on the northern Papuan coast. On this day, 18 December 1942, many young Australians would die, their broken bodies strewn among the coconut palms, their only garlands the heavy fronds stripped from the trees in the course of the battle. When night fell, the stars of the Southern Cross would shine upon these fallen sons. This would be the day the infantrymen of the Australian 2/9th Battalion kicked open the door to Buna, a task that had been beyond two regiments of American infantry for over a month.

The United States 32nd Division, whose soldiers wore a red-arrow patch on their sleeves, was made up of units from the Michigan and Wisconsin National Guard. Commanded by Major General Edwin Harding, it had been the first American division sent from Australia to New Guinea; its lead elements flown to Port Moresby on 15 September, at the height of the Japanese threat. The 126th Regiment came by sea, arriving on 26 September; the 128th arrived by air. The 2/126th Battalion was the only American unit to walk across to the north coast, traversing the Jaure Trail, which was further east than the Kokoda Trail and crossed the 2800-metre Ghost Mountain. The terrain was the enemy here, and it was merciless. As Sergeant Paul Lutjens observed, ‘It was one green hell to Jaure.’ Another soldier observed that ‘combat later was almost a relief.’ The battalion reached Jaure on 28 October, though without its commander, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Geerds, who had had a heart attack. After the experience of the 2/126th, the rest of the regiment went across the ranges by air and by 9 November had gathered at Pongani. Meanwhile, the 128th Regiment was flown into Wanigela, then moved up the coast to Oro Bay by luggers, a trying task in itself. The Australian 2/6th Independent Company went with them.1

The 32nd Division made its first contact with the Japanese defences at Buna on 16 November. As Lieutenant Colonel Kelsie Miller, the commander of the 3/128th Battalion, noted, they were stopped cold. And they remained so. All troops who fought in New Guinea, whether American, Australian or Japanese, had considerable difficulty adjusting to the conditions there, and Harding’s division had more trouble than most. Warren Force, made up of 1/128th and 3/128th Battalion, was at a standstill on the eastern (coastal) flank, and Urbana Force, made up of 2/128th and 2/126th Battalion, was bogged down to the south of the Buna Government Station.

Major Harry Harcourt was in command of the Australian 2/6th Independent Company, deployed to cover the Americans’ inland flank at New Buna strip, a decoy airfield that was never used for operations. Decorated three times serving with the British Army in the First World War and twice more in Russia, the 47-year-old Harcourt was undoubtedly the Allies’ most experienced front-line officer at Buna. On 21 November, Harcourt’s men were to advance with the Americans, but Miller’s 3/128th Battalion was late reaching the start line and was also bombed by US aircraft. When it finally advanced, the 3/128th was almost immediately stopped by the staunch enemy defence, taking forty-two casualties. Harcourt’s sixty men, led by Captain Rossall Belmer, cleared some enemy positions and advanced along the airstrip, but this left the troops open to enfilading fire from their right, where Miller’s infantry had not progressed. Miller’s battalion was then moved to the coastal flank, where it attempted an attack towards Cape Endaiadere on 26 November. That operation had no more success than the first: this time it cost seventy-seven casualties.2

Meanwhile, Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Smith’s 2/128th, its advance channelled along a narrow neck of land between Entrance Creek and Girua River, was similarly unsuccessful in attacking north along the Ango road towards Buna Government Station. Held at a point known as the Triangle, the Americans would hardly move until January. They were up against formidable, though isolated, opposition. Lance Corporal Kondo, serving with the 500 marines of Captain Yoshitatsu Yasuda’s naval unit, wrote on 5 December, ‘Every day my comrades die one by one and our provisions disappear day by day.’ Four days later he remarked, ‘This may be the place where I will meet my death. I will fight to the last.’3

When Captain Gordon King, Harcourt’s 2IC, arrived at Buna on 27 November, a frustrated Harcourt told him, ‘Well, they’re going to put in another attempt tomorrow, and I want you to go and have a look.’ The next day King watched, and his men waited, as an artillery barrage was laid down and the air strikes went in, but there was no sign of movement from the Americans. King made his way to the adjoining American company and ‘found these four guys sitting in a hole in the ground.’ They were the company’s officers. King asked them, ‘Are your guys doing an attack at the moment?’ ‘Yes, the guys are going in,’ one replied. ‘The top sergeant takes them in.’ King then asked, ‘Well, what about you fellows?’ The reply rocked him: ‘Oh, we’re too valuable, there’s Japs out there, you know.’ King then went forward, found the top sergeant and discovered that ‘he was no more taking anybody in than he was going to fly over the moon.’ King informed Harcourt, who told him, ‘That’ll do me,’ before heading off to see Harding.4

Lieutenant General Herring, who was Harding’s commander, had already sent his liaison officer, Lieutenant Colonel William Robertson, to meet with Harding that same day, 28 November. When Harcourt gave his report in Robertson’s presence, Harding admitted that he was out of touch with the forward troops. An astonished Robertson passed this on to Herring, who then told General Blamey. Meanwhile, General MacArthur had also received a damning report from Brigadier General Stephen Chamberlin, his Chief of Operations, whose deputy, Colonel David Larr, had visited Buna from 27 to 28 November. MacArthur expressed his ‘very serious disappointment with Harding’ to Blamey.5 On 30 November Harding was replaced as overall commander at Buna by Lieutenant General Robert Eichelberger. ‘Bob,’ MacArthur told him, ‘I want you to take Buna or not come back alive.’ Heavy American attacks at Buna that same day got nowhere.6

Eichelberger flew across from Port Moresby to Dobodura on 1 December and, after meeting Harding, visited the front line the following day. The challenge in front of him stared back from the hollow eyes of his fever-ridden men. ‘Yet,’ as he later wrote, ‘to evacuate all those with fever at Buna would have meant immediate victory for the enemy.’ He later told the American officers, ‘You don’t look like officers and you don’t look like gentlemen,’ and said he would not address them until they looked like both. One then asked Harry Harcourt where the laundry unit was and was told his men could use Harcourt’s facility, 50 metres down the track. There the Americans found some of Harcourt’s men washing in a creek.7

On 2 December, the Americans failed in another attack on New Strip. Harcourt’s men again had to advance with an open right flank, and Captain Belmer was killed near the bridge over Simemi Creek. Another American attack up the Ango road towards Buna Government Station also failed. Having personally witnessed this latest failure, Eichelberger relieved both Harding as divisional commander and Colonel John Mott as commander of Urbana Force. Brigadier General Albert Waldron, who replaced Harding, was wounded the following day; two weeks later, so was his replacement, Brigadier General Clovis Byers.

Bren-gun carriers were now brought into the fray. Five carriers from the 2/7th Battalion’s carrier platoon had been unloaded at Oro Bay on 29 November. With deep coastal creeks preventing movement to Buna by land, the carriers were towed up the coast on barges. They arrived on the night of 3–4 December, whereupon the unit 2IC, Lieutenant Ian Walker, discussed the use of the carriers with the Americans while Lieutenant Terry Fergusson looked over the approach route. After an artillery barrage on the morning of 5 December, the carriers moved out of cover into a clearing in front of the Japanese defences. The defenders were men of Captain Hitabe’s company, from Major Heikichi Kenmotsu’s III/229th Battalion which had arrived from Rabaul on 18 November.

‘Jock’ Taylor’s and Norm Lucas’ carriers moved to the right flank, Fergusson kept his carrier in the centre, and Cec Wilton’s and James Orpwood’s carriers took the left. The five carriers moved at walking pace so the American infantrymen could follow, but the Yanks hardly got past the start line. After advancing less than 50 metres, Lucas’ carrier bellied on a log, and its crew could provide support only from that position. Taylor’s carrier kept going and got close enough to a bunker for the men to throw grenades in before backing off to let the Bren gun take aim. The Japanese retaliated with mortar fire. The first round landed just behind the carrier, but Taylor managed to get behind the enemy position and fire on its rear entrance. When he left the carrier to deal with the enemy grenade throwers, he could see Fergusson standing up in his carrier but was unable to hear him. Still unsupported, Taylor yelled out, ‘Where are the infantry?’8

Taylor’s carrier then came under heavy fire from the left flank, but its thin armour held. However, when Taylor stood up and tried to engage the enemy with a Bren, he was shot in the left arm. The driver, Angus Cameron, then backed the carrier into a depression to raise its front end for better protection, and covered Taylor as he made his way back. Despite his wound, Taylor pulled pins from grenades and handed them to Cameron to throw. When the vehicle would not restart, Cameron went back for help under cover from Leslie Locke, the rear Bren gunner, who had also been hit by shrapnel.9

Meanwhile, Fergusson’s carrier had bellied on a coconut log. Fergusson, who had taken over from the wounded driver, stood up and was shot. When Frank Davies tried to move Fergusson out of the driver’s position, he too was shot. So was Tom Armstrong, who would die from his wounds. From Taylor’s carrier, Locke could see the enemy snipers standing on platforms up in the coconut-palm trees firing down into the carriers. Locke shot and killed the sniper who had got Fergusson. Despite his wound, Taylor again left the carrier, this time to help the mortally wounded Fergusson. Locke covered him until he was also hit, wounded in the stomach. Before he collapsed, Locke managed to tussle with and kill another Japanese. Locke lay on the ground for three or four hours, feigning death and when darkness fell, crawled back to the American lines. Hearing a rifle click, he called, ‘Yank.’ Two of the Americans picked him up and took him to the regimental aid post. When his mates later visited Locke in hospital, he told them, ‘You can’t kill me.’10

Wilton’s carrier, like Lucas’s, had bellied on a log a short distance from the start line. After the two Bren gunners were wounded by snipers firing from the treetops, the crew left the carrier and regained the American lines. Further forward, Orpwood’s carrier had also been halted and Orpwood mortally wounded. Two other crewmen, Harry Kemp and Brian Conway, were also wounded while giving covering fire. At about 1020 Lieutenant Walker headed up to the Bren carrier graveyard, moving across the clearing to the carriers on the left flank. After trying unsuccessfully to drive Orpwood’s carrier off the log, he moved to another abandoned carrier and was shot dead.11

Open at the top and only lightly armoured and armed, the Bren-gun carriers were no tanks. Grenades and snipers soon took care of them, putting them all out of action within thirty minutes. Accompanied by the American infantrymen, the carriers could have given useful support, but they had been hung out to dry. The unflinching bravery of the five carrier crews was not enough to save them.

One of the defenders, First Lieutenant Jitsutaro Kamio, wrote: ‘They attacked with five tanks at their head . . . Everyone was surprised at first at the appearance of the tanks, but we repulsed them with hand grenades and other things. Three tanks stalled about 40–50 metres in front and it seems that they were about all killed.’ Lieutenant Suganuma noted, ‘It was very effective when hand grenades were thrown in them.’ Another wrote: ‘Four tanks had some trouble or other. In that condition they were bombed during the night . . . The platoon, hearing of these tanks, made trenches and reinforced the shelter positions.’ Of the infantry action, Sergeant Yamada observed, ‘The enemy has received almost no training. Even though we fire a shot they present a large portion of their body and look around. Their movements are very slow.’ First Class Mechanic Satanao Kuba saw beyond the successes of the day and wrote, ‘When the sun sets in the west we look at each other and wonder that we lived till now.’12

There were some brave Americans at Buna that day. One was Staff Sergeant Herman Bottcher, one of the rare NCOs with battlefield experience. That experience had come fighting with the Republican Army in Spain, a stint that had denied him American citizenship. Of German birth but staunchly anti-fascist he fought for his adopted country as a German citizen. During the attack north up the Ango road, Bottcher took his eighteen-man platoon through to the coast at Giropa Point, from where they could command the coastal strip. With one machine gun, they proceeded to fire at Japanese moves along the beach to either side—and held their position for seventeen days. The wounded Bottcher was promoted in the field to captain. Captain John Milligan, who later met him, observed, ‘He was keen to go out and have a smack and was a fine soldier, but there were few like him.’13 Like many of the finest, the highly-decorated Bottcher did not see the war’s end; he was killed in the Philippines on the final day of 1944.

Having served with distinction in the Middle East and then broken the Japanese at Milne Bay, General Blamey knew that the Australian 18th Brigade could do what the Americans had failed to do: take Buna. He was still out to show MacArthur that the best infantrymen in New Guinea were Australian.

Lieutenant Colonel Clem Cummings’ 2/9th was the first battalion from Brigadier George Wootten’s brigade to reach Buna. Cummings was held in high regard by his men, partly because he owned a cattle property. Despite strict wartime rationing provisions, he had made some of the herd available for his men while they were in camp in Queensland.14 Cummings’ battalion left Milne Bay on three Australian corvettes, HMAS Ballarat, Broome and Colac, on 13 December, heading along the northern Papuan coast towards Buna in heavy rain. Ron Berry wrote, ‘We have no shelter & we are bitterly cold. Using gas capes as rain coats but those soon get soaked. The deck seems to hold water.’ The corvettes were aiming for Oro Bay, but they overshot it and the next morning arrived off Buna. When an enemy plane circled and started dropping flares, the corvette captains decided to pull back to Oro Bay. Only Cummings and a single platoon managed to disembark. At midday on 15 December, the rest of the battalion began the 30-kilometre trek back up to Buna. The heavily burdened infantrymen trudged along the beach, crossing creeks as they went, and arrived the next morning. Berry wrote, ‘Carrying parties all that day and next getting everything into position for the attack.’15 Having had his American infantry get nowhere in four weeks, MacArthur now wanted the Australians to take Buna immediately, and the battalion was ordered to attack the next morning. But the Regimental Medical Officer had other ideas. He demanded a day’s rest for the weary men; it was granted.16

Eight M3 Stuart tanks from the 2/6th Armoured Regiment would support the Australian attack. They had been unloaded at Oro Bay, towed on barges to Hariko, and then driven up the coast by night, making the final move to the start line with one track in the ocean to fool enemy observers. The Stuart was designed as a light tank and, though not ideal in the role of infantry support, it was a marked improvement on the Bren-gun carrier, being fully armoured and possessing a main gun. Its greatest deficiency would prove to be the crews’ lack of training in lending support to infantry troops, particularly in such close country. The infantry, too, would have to learn on the job how to work with the tanks.

For the attack on 18 December, the support plan was for one hour of artillery fire at normal rate and then ten minutes at heavy. What the men got was half an hour of fire at slow rate and ten minutes at normal.17 Des Rickards was in charge of the Vickers machinegun platoon, and at 0650 he gave the order to open fire by spraying the tops of the palm trees for snipers. As the Vickers guns opened up, so did the mortars. The din masked the sound of the Stuarts’ engines starting up. At 0700, a section of tanks moved forward, with the Vickers guns firing between and above them. When the infantry came through a few minutes behind the tanks, Rickards called a halt just as the water in the machinegun cooling jackets reached boiling point. When the infantry passed Rickards, ‘All hell broke loose as the Japs opened up with everything they had.’18

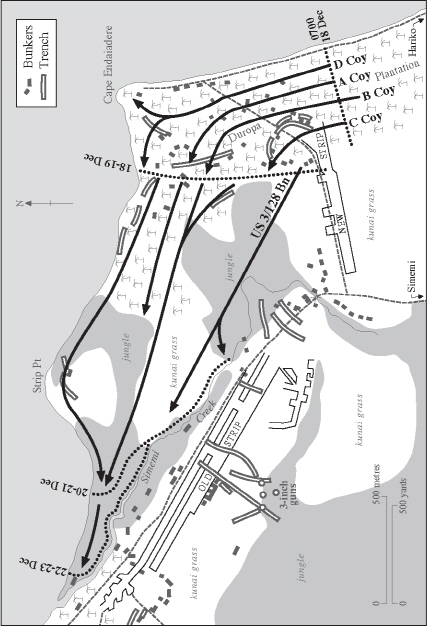

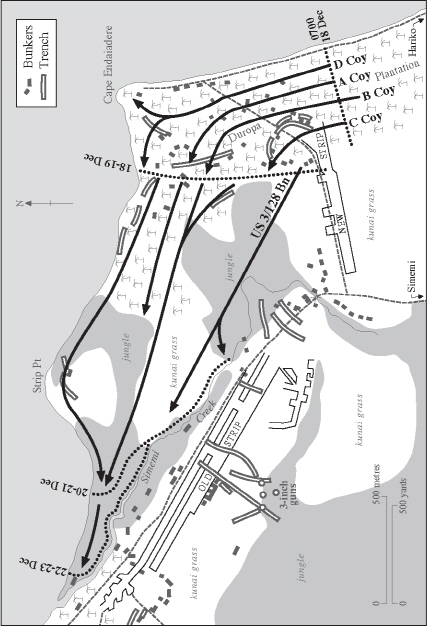

Buna: 2/9th Battalion, 18–23 December 1942

Captain Roger Griffin’s D Company went in on the right, the start line marked by a Bren carrier abandoned by the Americans two weeks before. Lieutenant Bill MacIntosh, whose 17 Platoon had the sea on the right flank, had crawled forward on the previous evening and spotted a Japanese machinegun position at Cape Endaiadere. Further inland, he had identified the prominent mound of another position among the coconut palms. His platoon was supported by Corporal Evan Barnet’s tank, which advanced, horn blaring, through the knee-high kunai grass between the rows of untended coconut palms. MacIntosh, who carried a Tommy gun and led from the front, directed Barnet against the first bunker position. After the main gun had opened a gap, the infantry moved in with grenades. Two enemy soldiers escaped. When one shot George Tyler in the arm, Tyler turned and shot him dead. The other headed into the sea, where George Silk photographed him detonating a grenade against his head when he was asked to surrender.19

On the left side, Sergeant Bob Thomas’ section came up against a bunker that MacIntosh had missed on his recon. The enemy soldiers inside it were armed with Bren guns and grenades they had gathered from the knocked-out carriers. Thomas came under fire as he dashed for the post. He was spattered in the face with grenade fragments, but still managed to shoot two defenders. Another Japanese soldier had poked his Bren gun through the embrasure. Thomas wrestled it away from him and used it to kill him as well. MacIntosh’s platoon reached Cape Endaiadere by 0750, having only lost one man killed and five wounded.20

Lieutenant Tom ‘Bluey’ Sivyer’s 18 Platoon was on the inland side of MacIntosh, supported by Lieutenant Vic McCrohon’s tank. The platoon immediately ran into heavy fire spitting from the concrete bunker MacIntosh had spotted the previous evening. Sivyer and platoon member Frank Rolleston were moving past one of the Bren carriers when an enemy machine gun sent clods of earth into the air. Rolleston ducked behind the carrier, but Sivyer was killed by the same burst of fire. From a covered foxhole, a defender then threw two grenades at Rolleston, who hugged the ground; he was unharmed. When he next looked up, he saw Charlie Alder standing over the Japanese position with his Tommy gun blazing. Alder then turned his attention to a bunker. After firing into the door, he threw in a grenade but it was thrown back before it exploded. Two or three defenders rushed out of the bunker, only to fall to Alder’s Tommy gun and Rolleston’s Bren.21

Sergeant Dave Prentice took over from Sivyer before being wounded in the head. Alder bandaged him before dashing across to check on Ray Buckley and Merv Osborne, who were manning the Bren gun that had stopped firing. Bending over them, he found that both were dead. A split second later, so was the selfless Alder, probably hit by the same sniper. Alder’s mate, ‘Scotty’ Wright, who had talked with him just moments before, was devastated. ‘This to happen, after three years,’ he cried out. Clint Graham was also hit while trying to spot the sniper, but the bullet went clean through his helmet without wounding him. Soon, only nine men remained of the thirty from Sivyer’s platoon who had crossed the start line.22

Captain Griffin sent Sergeant Harold Armitage (serving as Sergeant Walters) forward to take over the platoon. Two bullets whistled past Armitage before a third found its mark and he was killed. The platoon remained pinned down some 25 metres from the enemy post. It was originally manned by twelve men with two LMGs and a sniper’s rifle. By the time it was taken, the following morning, only two defenders remained.23 Meanwhile, Warrant Officer Vince Donnelly’s 16 Platoon followed the two leading platoons towards the cape. They took fire from some positions that had supposedly been cleared, but they made it.

Trooper ‘Ted’ Nye was the driver of Sergeant Jack Lattimore’s tank, the third tank in McCrohon’s troop. He later told Dudley Leggett that, ‘They tried to get around the point and we gave them hell. The 37-mm gunner plasted them, and the hull gunner just picked them off.’ Then the tank was called back to help 18 Platoon further inland. As it lumbered through heavy scrub, the infantry lost touch and an enemy defender placed a magnetic mine on the back of the tank. The blast took the arm off the assailant but also blew out the battery, putting the radio out of action. The tank then bellied on a log close to a bunker. A defender darted out and tried to set the vehicle alight. Ordering Nye to shut down the engine, Lattimore and two other crewmen tried to keep the assailants at bay by firing through the pistol ports. But a sniper had the turret in his sights, and every time they tried to get out, he fired. Fortunately, Barnet’s tank arrived to give covering fire, allowing Lattimore and his crew to escape.24

The role of the tanks was crucial. After the infantry indicated an enemy position, the tank would get to within 5 metres of it and blast a hole in the bunker with 37-mm rounds from the main gun. An infantryman would then move up with grenades while the tank’s machine gun took care of any defenders who tried to flee.25 The hull gunner would also fire his machine gun at the tops of the palms, probing for enemy snipers.

After Cape Endaiadere fell, the ‘Kilcoy taken’ signal was transmitted and supplies were sent forward. Ron Berry wrote, ‘Once word came back that the point was clear of enemy, we loaded barges and ran the gear up the coast within a few hundred yards of the Cape.’26

Captain Bob Taylor’s A Company attacked on the left flank of D but lost its three supporting tanks early. Lieutenant Grant Curtiss’ tank was the first casualty: it ran up onto a stump hidden in the kunai grass and got stuck. The Japanese defenders lit a fire beneath it, but the crew got out under covering fire from the infantry. Sergeant John Church tried to recover the bellied tank with his own, but once the flames took hold, Curtiss’ tank burned out in a huge blaze with many explosions. It was vital to keep the tanks safe, so when Ernie Randell spied around a dozen enemy soldiers in a trench watching a tank go by, he promptly took care of them. He also got busy with a bunker, but when he tossed grenades through the embrasures, they were hurled back. It became a very nervy business, with Randell holding his live grenades for as long as he dared while dodging the snipers amid the noise and confusion.27

Captain Cecil ‘Tom’ Parbury’s C Company moved up on the left flank of A to complete the line through to the Americans. Parbury had taken over command only the previous day from Captain Alec Marshall, who had been evacuated with scrub typhus. Parbury put Lieutenant Frank Pinwill’s 13 and Lieutenant Roy De Vantier’s 14 Platoon up front, with Warrant Officer Jim Jesse’s 15 Platoon behind them. But with no tank support, the company suffered grievously: within ten minutes it had lost a staggering forty-six men, over half its total strength of eighty-seven. De Vantier and all his NCOs but one were killed as the company advanced barely 100 metres, only half-way to the enemy’s front-line positions. Despite coming under constant fire since the first American attacks, the Japanese defenders had hoarded their ammunition. ‘We are waiting for one good shot and will not fire,’ Lieutenant Suganuma wrote five days earlier.28 On this day his men had ample good targets.

Parbury ordered the rest of his men to ground, where they sheltered among the logs from the felled coconut palms in the metre-high kunai grass. Harry Dixon observed, ‘We knew the bastard was there but we couldn’t see him.’ George Morey’s section was sent to outflank the position, but all the men were killed before they had gone 15 metres. Parbury later told Official Historian Gavin Long that there were sixteen bunkers in his area, six to his immediate front and the others further back.29

Des Rickards had orders to move the Vickers guns up to support Parbury. When a runner did not return, Rickards went out to find Parbury. He crawled about 200 metres until he was behind a fallen palm tree. As he rose to cross it, a machinegun burst caught him under the right arm, and another struck his left elbow. Two gallant Americans crawled up, got Rickards onto a stretcher, and dragged him back.30

At 1300, Jim Jesse’s reserve platoon and three tanks under Lieutenant Curtiss were finally sent in to help Parbury’s shattered platoons. Just before the tanks attacked, three Japanese soldiers targeted the right-hand tank with Molotov cocktails, but they were beaten off. In Captain Norm Whitehead’s tank, both he and the gunner, Gordon Bray, had been wounded when an enemy soldier climbed up and fired through the vision slit. Lieutenant Colonel Charles Hodgson then took over the tank. With the vision slit broken, Hodgson had to stick his head out of the turret to direct the driver. The replacement gunner, Bob Taylor, put three shots into the first bunker and then handed four grenades up to Hodgson to throw into the blasted opening. He also shot two defenders with his pistol. Under constant sniper fire, Hodgson was finally hit in the head, and he fell down inside the tank.31 The tanks had made the difference here, destroying eleven bunkers and emptying another five. Jim Jesse showed great initiative by firing Very flares at the bunkers to pinpoint them for the tanks. Over eighty Japanese bodies were counted in the area, not including those inside the bunkers. These defenders had been told to hold their positions to the last man and they had.32

Colonel Cummings’s headquarters was only 20 metres behind the start line, but all of its phone lines had been cut during the fighting. When the adjutant was injured, Lieutenant ‘Kitch’ Beattie was sent further forward to find that the few men left in A Company were holding a 100-metre front, while D Company held the line through to the sea. ‘The boys were still full of fight,’ Beattie noted.33

On the left, Parbury’s C Company had taken the heaviest losses. Cummings now ordered Captain Arthur Benson, whose B Company remained in reserve at battalion headquarters, to take his men forward on the left flank, where the resistance had been greatest. As the company went forward, Major Bill Parry-Okeden ‘saw Bill Howell and Bob Heron out of the corner of my eye. I gave them a smile and told them to go to it, you old buggers.’ It was the last time he would see the two officers alive. He later wrote, ‘I can still see the set look on their faces.’34

Though the forward troops had already moved through the area ahead of Benson’s company, it was by no means cleared. Many of the Japanese dugouts were only for shelter, so after the main support fire and attacks went through, the enemy soldiers came out and occupied the adjacent trenches and weapon pits.35 Grahame ‘Snow’ Hynard recalled, ‘We had orders not to help anyone, to keep going. The Japanese positions had creepers and vines growing over them and could not be seen until you were on top of them.’ The company, he said, ‘ran right into hell itself.’36 With Benson trying to direct the company from a hole further back, it was Corporal Tom Clarke who took command at the front and led the men through.37 He climbed up onto the tanks to tell their crews what was required, then followed behind to grenade the targeted bunkers. Refusing cover, the inspirational Clarke was twice wounded on that first day. With one tank and eleven men, he destroyed twelve bunkers. ‘I have never seen a man with more guts,’ said one of his soldiers.38 Benson’s company took about eight hours to reach the forward positions, but only twenty of the ninety-six men who started out made it: all three platoon commanders were killed and the company 2IC was wounded.

Kitch Beattie had to deal with a bunker behind the front lines, near battalion headquarters. It looked like a mound of sand, built of coconut logs with four embrasures and crawl trenches at two ends. He tossed in a grenade at one end while a rifleman waited at the other. But one of the defenders charged straight out at Beattie, firing his pistol all the way and wounding Beattie in the side of his face. The Australians spent the whole day trying to coax out the remaining defenders before finally throwing in a drum of petrol and a grenade.39

The casualties had been heavy, but as Wootten observed, would ‘have been far heavier had the attack not been pressed home with the determination that was shown.’40 One of the III/229th Battalion defenders, Toshio Yoshida, was wounded by tank fire and captured during the fighting. He told his interrogator that three companies from the battalion had faced the Australians from the coast to the Simemi Bridge at the south end of New Strip, with a fourth company in reserve. For the past ten days the men in Yoshida’s unit had not fired their weapons, conserving their ammunition for the expected onslaught. The battalion was at about two-thirds strength at the time of the attack: some 400 men, many of whom had now fought to the death.41

Nerves were strained that night on the perimeter. When Brigadier Wootten arrived at battalion headquarters, Parry-Okeden wryly observed, ‘I thought the heads must be pleased but what about all those fine chaps lying stiff on the battlefield . . . He [Wootten] turned to me with a cheerful smile and asked if I had any worries. What about the dead bill.’42 George Wootten knew all about the dead bill. He had seen his first dead Australians on the first day at Gallipoli and so many more since, from Passchendaele in that war to Tobruk and Milne Bay in this. On this day, the 2/9th had had five officers and forty-nine men killed, and another six officers and 111 men wounded.43 And it was only the first day.

Having taken Cape Endaiadere, the 2/9th pushed westward, aiming to clear all enemy positions north of Simemi Creek up to the creek mouth. On the second day, Corporal Les Thorne, a section leader in MacIntosh’s platoon, attacked a number of bunkers with a Tommy gun and grenades. It was dirty and dangerous work, and it was indispensable. No matter how fine the officers or how strong the support, the 2/9th’s success ultimately rested on men like Thorne, who had the courage to close with the enemy bunkers and capture them.

On 20 December, Ron Berry and 16 Platoon, to which he had been attached from the transport unit, moved up past the stinking bodies of the Australian and Japanese dead. With tanks in support, they advanced along the rows of coconut palms, firing into the tree-tops to dislodge any lurking enemy snipers. When a patch of jungle stopped the tanks, the infantry had to go on alone. They emerged into an area that had been blasted out of the jungle. Wading through swampy ground, they were sitting ducks for snipers, who opened fire from well-hidden positions along Simemi Creek. As the men withdrew, the Japanese dropped mortar bombs onto them and two men were wounded.44 Again it was Thorne to the fore, laying down covering fire as Bill MacIntosh and Eric Christenson, the latter in his first action, went out to get the wounded from under the noses of the Japanese.

Parbury’s company advanced through kunai grass that was above their heads, following the tanks as they moved parallel to the coast. The kunai was like a thick blanket, trapping the Australians in steamy, airless heat. Parbury said it was ‘so hot that men were collapsing.’ When Lieutenant Pinwill’s platoon stumbled on a Japanese position, three men, including Pinwill, were killed. Devastating mortar fire followed, and another nineteen were wounded, including Parbury.45 Clyde Coop, Parbury’s runner, was valiant. ‘He showed no fear,’ Jim Jesse later said. At times Coop seemed to be staging a war of his own, standing on bunkers to bait the enemy and going off on sniping missions with the casual aside, ‘I think I’ll go pay my respects to the Japs.’46

On the morning of 21 December, the twenty-one men of Vince Donnelly’s 16 Platoon continued the advance to Simemi Creek. Before leaving with them, Ron Berry wrote in his diary: ‘I have a feeling there is trouble ahead for someone.’ The men found ‘Jock’ Milne, who had been shot on the previous day and was in a bad way. They vainly looked for the sniper who had shot him before calling up stretcher bearers to take Milne back. Then Berry spotted men jumping into weapon pits up ahead, and the section leader, ‘Ike’ Gill, yelled, ‘Japs!’ The men scrambled for cover, leaving Milne on the ground. Berry got behind a large stump, but as he prepared to fire, a bullet struck his rifle, shattering the butt and wounding him. Other men fell, the platoon commander among them. Berry wrote: ‘Vince Donnelly drops like a stone.’47

Donnelly survived, and later recalled how the bullets cracked around him as he dropped to the ground for cover. When he lifted his head, he was stunned by a glancing blow from the left. Alongside Donnelly, the Bren gunner, Kenny Grant, was killed.48 Ron Berry made his way back to the aid post past scenes of horror. Bodies had been buried in shallow graves along the track, but many remained in the open, among them the corpse of a Japanese sniper, lying in two pieces under a palm tree. He had been attached to the tree for safety by a rope around his waist, and after death had hung there until his body began to decompose and both parts fell to the ground.49 Even at the aid post there was danger: Captain Alec McGregor was wounded by Japanese shelling on the following day.

Meanwhile, ‘Jock’ Milne remained out on the battlefield, where he eventually died. The acting intelligence officer, Bill Spencer, later found Milne, who was from his section. A note with his body said that Jack Allen was nearby, also wounded. Allen was recovered alive, but he too died. Too many good men were dying.

On the next day, 22 December, the attacks continued. Cummings phoned through to the forward companies to say, ‘We’ll take Simemi Point if Parry-Okeden and I have to go in with a bayonet ourselves.’50 There were two tanks available, but in the swampy terrain they had trouble getting anywhere, just ‘pushing a wave of slimy mud in front of them.’ The need for constant changes of direction as the tanks tried to find a way forward meant that here they were of little help to the infantry.51

All the men were riflemen now, spread out in an extended line from the beach to Simemi Creek, advancing on Simemi Point. Having lost all his platoon commanders, Roger Griffin led the attack on the final enemy position east of the creek and died at the head of his men as he rushed forward to cut off the Japanese withdrawal. Inspired, his men reached the point at 1600, completing the task the battalion had been set. Parry-Okeden had watched Griffin go forward that morning, once more unto the breach: ‘I will never forget the look poor old Griffin gave me. Somehow I think he knew that he was going to get it.’52

There were more casualties in the days that followed. Cummings was among them, wounded when his headquarters was shelled on 24 December. Parry-Okeden took over the remnants of the battalion, and later wrote, ‘Like everyone else at this stage I was completely buggered and did not relish the thought of this great responsibility.’53 Yet there were more battles to be fought, and soon.

After the war, the men of the 2/9th Battalion would proudly take their place in the annual Anzac Day march through Brisbane. Year after year, they gathered at the same locale to form up and march behind their revered Colonel Cummings. One year they played a trick on him, and hid around the corner. ‘Where are my boys?’ a concerned Clem Cummings asked.54 He might well have asked the same question at Buna.