10

‘They came like the rain’

Wau

January to February 1943

Flight Lieutenant David Vernon left for work early on 6 January 1943. He made his way down to the foreshore at Cairns, where a marine-section boat took him out to his workplace, a Catalina flying boat at rest on the Barron River. The Catalinas of RAAF No 11 and No 20 Squadrons, based at Cairns, in far north Queensland, ranged across the South West Pacific Area carrying out aerial reconnaissance and other missions. On this day, one aircraft from each squadron was sent to search for a Japanese convoy that was moving along the south coast of New Britain from Rabaul, heading for Lae. Vernon’s Catalina took off just after 1100 and refuelled at Milne Bay before flying to the search area, where it arrived that night.1

Vernon picked up the convoy on his primitive radar screen southwest of Gasmata. The five transports were in line, led by one destroyer with two others alongside the transports. Cloaked by the night and intermittent cloud, Vernon closed in from astern, flying along the convoy’s axis. His approach was undetected: the ships went on steaming ahead, taking no evasive action.2 At 0430 on 7 January, Vernon’s observer, Flight Lieutenant George Leslie, was able to drop two 250-pound high-explosive and two 250-pound antisubmarine bombs onto the second last of the transports. Explosions rent the night, and the stricken vessel pulled out of line, its forward hold hit by Leslie’s second and its stern hold by the third bomb. Vernon’s attack had struck the Nichiryu Maru, which was carrying troops from the Japanese III/102nd Battalion. One of the destroyers, Maikaze, dropped out of the convoy to pick up most of the survivors, but 456 men were killed or missing and another eighty-five wounded. Vernon landed back at Cairns about 0900 and went home for a rest, after a solid twenty-two hours at the office.3

The other four transports in the convoy reached Lae the next day and landed the remaining two battalions. However, many of their supplies were destroyed on the beaches by concentrated Allied air attacks. The majority of the Okabe Detachment, made up of the 51st Division’s 102nd Regiment and commanded by Major General  Okabe, had been brought to Lae. The Japanese command announced that ‘this will send chills through our conceited enemy.’4 The failure of the Air Force to stop the convoy did indeed rock the Allied command. The Allied air commander, Lieutenant General George Kenney, responded that his airmen had ‘learned a lot and the next one will be better.’5 It was.

Okabe, had been brought to Lae. The Japanese command announced that ‘this will send chills through our conceited enemy.’4 The failure of the Air Force to stop the convoy did indeed rock the Allied command. The Allied air commander, Lieutenant General George Kenney, responded that his airmen had ‘learned a lot and the next one will be better.’5 It was.

On the day the convoy reached Lae, orders were issued for Brigadier Murray Moten’s 17th Brigade to be shipped from Milne Bay to Port Moresby and then flown to Wau. The first elements of the 2/6th Battalion arrived at the small gold-mining town on 14 January.6 Meanwhile, the Kanga Force commander, Lieutenant Colonel Norman Fleay—no doubt still smarting over his embarrassing retreat from Wau the previous August—planned a last hurrah. Fleay concentrated more than 300 commandos, supported by 400 native carriers, to carry out the largest operation thus far against Mubo, 20 kilometres inland from Salamaua. The commander hoped that he could destroy any Japanese troops occupying the village by deploying his men on the high ground that dominated three sides of Mubo. However, due to poor planning, ambitious objectives and a lack of proper communications, the operation was doomed from the start.

For Lieutenant Ted Byrne, it would be his first action, and for Lieutenant John Kerr, who had been in the Salamaua raid, his second. After the gruelling march across the Bitoi Valley, Captain Norm Winning told an exhausted Kerr to direct one of two ground attacks on Mubo. This attack, down Mat Mat Hill, which should have gone in at 0900, was delayed till 1330 while a Vickers gun and a 3-inch mortar were dug in. When Byrne asked, ‘What are your orders?’ Kerr replied simply, ‘Knock the Japs out.’ Byrne’s section waited in the burning sun on the eastern side of the ridge for the Vickers gun to open fire, the signal for the attack to start. After a scout reported, ‘There are twelve Japs sitting in the sun,’ Byrne quickly made up his mind. ‘OK, we are going to knock them out,’ he told his men. He would wait no longer: surprise would be his best support weapon on this day. But then the Vickers finally opened up, and Byrne’s section walked straight into heavy fire from the alerted defenders. Three of his men were killed and six wounded in what Byrne called ‘a bloody shambles.’7 The enemy positions on Mat Mat were well concealed in log bunkers, hidden in thick brush and screened by snipers. The attack stalled.

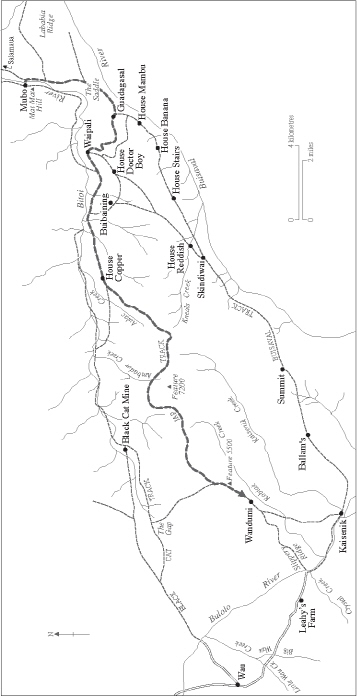

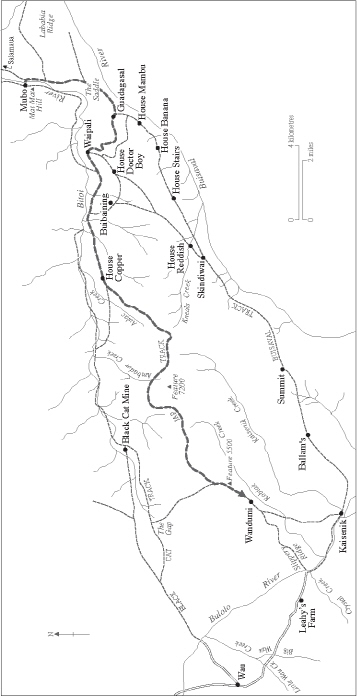

Wau to Mubo area

Across on Observation Hill, Lieutenant Bill Ridley’s fifty-man detachment had made the gruelling climb up the trackless hillside to get above the Japanese positions on Garrison Hill. Stephen Murray-Smith wrote: ‘The slope was severe and in addition there was no real path and our progress seemed to call for pushing through the undergrowth, clawing up rock faces and desperately scrabbling up falls of loose rock; bent double, faces drawn with tiredness and running with sweat.’8 Ridley’s men took the Japanese defenders by surprise, but the enemy snipers hit back. Peter McMenamin, who lay wounded in the kunai out in front of the gun position, called out for the others to leave him. Bravely ignoring the danger, Lieutenant Johnny Leitch, who had led a commando party in the Salamaua raid, went out to drag him in, and the sniper claimed another victim.9 Unable to communicate with the other attacking groups and therefore unable to attack down into Mubo, which was still under Australian fire, Ridley pulled his men out.

With the first troops from the Okabe Detachment rushed up to reinforce Mubo, the Australians would do well just to hold onto the vital Saddle position, from where both the Black Cat and Buisaval Tracks led to Wau. Just after dusk on 16 January, the Japanese attacked a platoon from Major Fergus MacAdie’s 2/7th Independent Company that was holding the track junction below the Saddle. The attackers got very close in the darkness, and eighteen of them fell to the Australian fire. Captain Geoff Bowen was also hit, shot through the pelvis. Bruce ‘Slugger’ L’Estrange carried him back up to the Saddle, but he died within days; he was buried overlooking the Saddle, and lies there still. The attacks continued throughout the night and into the next day, with Lieutenant Neal McKenzie’s section taking the brunt. There were now 350 enemy troops attacking. Concerned that his men might be cut off, MacAdie pulled them back along the Buisaval Track towards Skindiwai.10

One of MacAdie’s men remained behind, and for a considerable time. On the other side of the Bitoi River, George Butler had gone missing during the Mat Mat debacle. Getting water from the creeks around Mat Mat Hill and food from abandoned native gardens, Butler waited. Men from his own company finally found him, gaunt and delirious, on 16 March 1943, sixty-four days after he went missing.11

After the loss of the Saddle, the enemy made no move down the Buisaval Track towards Skindiwai. That worried MacAdie, who rightly deduced that the Japanese must be on the Black Cat Track. He discussed the situation with Major John Jones, who had come forward to Skindiwai with his company from the 2/6th Battalion. Jones decided he would cut across the ‘high road’ from Skindiwai to reconnoitre the Black Cat Track. MacAdie allocated one of his officers as a guide. Lieutenant Pat Dunshea, an astute and experienced bushman, was MacAdie’s junior section commander but had proven himself in the fight at the Saddle. Ted Byrne served with Dunshea throughout the war, and in his judgment, ‘Pat Dunshea was the toughest physical specimen, black or bloody white, in New Guinea.’12 On the morning of 21 January, Dunshea led Jones and his batman out of Skindiwai.

The three men pushed across the range until they reached the crest of the ridge overlooking Buibaining and the daunting chasm of the Bitoi River gorge. It was immediately obvious to Dunshea that enemy troops had moved through the area in some strength, some as recently as that morning. The Japanese had come up from Mubo to Waipali and then past Buibaining before descending the gorge to the Bitoi River. They had driven pitons into the rock and connected them with rope to help them negotiate 100 metres of near-vertical rock face. By grasping a tree and dangling out over the edge, Dunshea was able to see a Japanese party at the foot of the gorge, bathing in the Bitoi River. On the slope above the bathing point, about sixty troops were already ascending the Black Cat Track towards House Copper, a simple tin-roofed hut. ‘Take a look at that,’ Dunshea told Jones as he handed him the binoculars. Jones replied, ‘I can’t count the buggers either, but they’re Japs alright.’13

The Japanese had been moving along the Black Cat Track for four days; Dunshea and Jones had seen the first indication of the passage of some 1500 enemy troops. Looking closer, Dunshea observed that the well-disciplined Japanese had deliberately trodden in each other’s footsteps, preventing aerial observers from seeing how heavily the track was being used. The footsteps were quite deep—an indication that hundreds of men had passed, all carrying weighty loads. One of those men noted in his diary on 24 January, ‘After marching for nine days knapsacks and boots are badly worn, spectacles become blurred and we have no strength left to rub the rust off our swords.’14

However, back at Kanga Force headquarters Brigadier Moten was unable to think beyond the theory that the enemy force in the area was only a strong patrol.15 Moten certainly saw no direct threat to Wau, and sent the other three 2/6th Battalion companies out of the town. One went down the Bulolo Valley, another moved up the Buisaval Track on the heels of Jones’s men, and a third went to reinforce Captain Winning’s 2/5th Independent Company at Black Cat mine. On 22 January, Winning had sent a reconnaissance patrol along the Black Cat Track towards House Copper in an effort to determine the strength of the Japanese force. However, the enemy troops had already moved up an alternative track, later named the Jap Track, which branched off near House Copper. Two nights later, Winning’s men looked south across the valley from the Black Cat mine and saw intermittent glimpses of what looked like firelight through the trees on the adjacent ridge. These were the lights of the Okabe Detachment.16

Next day, it was confirmed that the Japanese were cutting a new track. Assuming that an attack on his position was inevitable, Winning sent a message to Moten that the enemy’s ‘patrol’ was swinging back towards the Black Cat mine.17 He was wrong on two counts: it was no mere patrol, and it was headed for Wau. Though Moten now had more troops available, he still did not recognise the threat, and sent the two newly arrived companies from Lieutenant Colonel Danny Starr’s 2/5th Battalion up to Skindiwai. He also ordered a three-way push to squeeze out the Japanese ‘patrol’. Jones’ company would move up behind from the Bitoi, Captain Hugh ‘Mick’ Stewart’s company would move down the Black Cat Track to link with Jones, and Captain Wilfrid ‘Bill’ Sherlock’s company, which had moved across from Ballam’s Camp, would advance east from the Wandumi area, outside Wau.

At dawn on 28 January, Jones’ company moved out of the Bitoi River gorge, following the Black Cat Track towards Wau. Pat Dunshea was one of the forward scouts, leading the struggling company up a kunai-covered ridge. He moved cautiously, some 20 metres behind the leading scout, until he was about 400 metres from House Copper. At this point, a giant fig tree, bereft of foliage, had fallen across the track. The first scout crawled through the tree limbs and went ahead, but he soon returned, firing his Tommy gun back up the track to the spot where had been ambushed. Dunshea joined in with a burst from his Tommy gun as a barking dog came down the track, followed by its handler. Firing in bursts of two or three shots to save ammunition, Dunshea scrambled down the steep slope. He shot the dog dead when it was almost on him, along with its handler. More enemy soldiers arrived and a shot from one hit Dunshea in the left hand. The same bullet damaged the drum magazine on his Tommy gun, so he threw a grenade, forcing the Japanese patrol back towards House Copper.18

With dusk approaching and his company’s advance stalled, Jones ordered his men to pull back to the kunai ridge for the night. He then sent for native stretcher bearers; four men had already been wounded, and the two stretcher cases each needed at least four carriers. Continuing the advance would risk even more casualties, so with ammunition and food running low and the company out of radio contact, Jones made his decision. ‘Rightly or wrongly,’ he later wrote, ‘I decided to get back to Buibaining.’19 Since Jones knew that the operation also involved an advance on House Copper from the other direction, his failure even to hold a blocking position seems unduly hasty.

Captain Stewart, approaching from the other direction, was carrying three radio sets, yet within five hours of leaving Black Cat mine he had lost all communications. Incessant rain and a muddy track meant further delays, and Stewart’s company did not reach the start of the Jap Track near House Copper until 1230 on the following day, 29 January. By then there was no sign of the Japanese or of Jones’ company. Under orders to make contact with the enemy force, Stewart sent his company along the Jap Track, a 2-metre-wide, ‘very well defined old track’ that ‘you could drive a jeep down.’ His men soon came upon a dying Chinese carrier, who was able to tell Stewart that the track had not been used for two days. After a runner brought new orders, Stewart took his company back to hold the junction before returning to Black Cat mine on 31 January.20

Back on the outskirts of Wau, Captain Bill Sherlock’s company had concentrated at Wandumi village by 27 January. His men were joined by about twenty 2/5th Independent Company commandos under Lieutenant Kerr. Sherlock badly needed the extra men, as his company was at less than half strength, with only three officers and fifty-seven men spread among the three platoons.21 Lieutenant Edward St John led 9 Platoon, but the other two had sergeants in command, Charles Payne and Jim Wild. Patrols that day had encountered Japanese scouts at the eastern end of Wandumi Ridge. Ordered to advance up the track the next morning, Sherlock’s men would soon find how many more were behind them.

That same afternoon, General Okabe and Colonel Kohei Maruoka met at Wandumi Trig Point, from where they could see Wau spread out in the valley below. Maruoka then conferred with his two battalion commanders, Lieutenant Colonel Shosaku Seki and Major Kikutar Shimomura, to plan the final advance on Wau. Seki’s men were ready to move at 1900, just after dusk. But the track down to the eastern end of Wandumi Ridge followed a narrow path through thick jungle, and some sections were fairly steep. Though patrols had already gone ahead, in the inky darkness it was nearly impossible for the troops to find the way.22

When Seki’s men did finally emerge from the jungle, they found that the Australians had occupied Wandumi village and blocked the track along Wandumi Ridge to Wau. The enemy advance faltered. When Sherlock heard the Japanese approaching, he and his men moved back from the village to the ridge, hugging the ground as mortar rounds fell. As the first enemy soldiers moved along the ridge-top track in the pre-dawn light, Johnny Noble took aim with his Bren gun, but when he pressed the trigger he heard only a loud click—the magazine had not been fitted properly. Noble snatched up the weapon and jabbed the first soldier he saw in the stomach before letting fly with his fists. But his mates’ fire drove back the Japanese.23

Now aware of the scale of the enemy attack, Sherlock positioned his men back along Wandumi Ridge, a narrow and well-defined feature that wound back to the Bulolo River. They had a good field of view both north and south along the ridge’s entire length, and holding it would seriously delay any enemy advance on Wau airfield, only 6 kilometres away across the Bulolo River. With the first probes stymied, the Japanese opened up with heavy mortar and machinegun fire, though most of the mortar bombs failed to explode. After an hour, enemy troops began moving around the right flank, and Sherlock pulled his men 300 metres further back along the ridge. Sherlock placed his strongest platoon, St John’s, forward on and behind a prominent knoll. He positioned his second platoon on the left flank, where the ridge widened, and kept his third platoon in reserve. Kerr’s commandos were placed between the forward and reserve platoons, one section each on the left and right, and one in reserve. The new positions enabled the Australians to overlook any enemy moves from the front and the flanks. Sherlock’s headquarters was further back, in defilade from any frontal fire, though this also meant he could not see the forward positions. There was minimal cover on Wandumi Ridge, and with digging difficult in the hard ground, most men lay flat in the kunai grass, peering through their weapon sights over the crest of the ridge.24

At 0705 Sherlock reported that more than seventy enemy troops with mortars and a machine gun were in Wandumi village and attacking up onto the ridge against St John’s platoon on the knoll. Fearing that the attackers were coming around the back of the knoll, Sherlock deployed a group of commandos in behind St John on the right side of the ridge to target enemy troops advancing across the open country south of the ridge. Careful not to betray his position, Bill ‘Mucka’ Lines was firing single shots from his Bren gun through a gap in the kunai grass as the troops passed less than 50 metres below him. However, not all the Japanese were ignoring Lines’ fire. One crawled up the side of the ridge through the kunai grass, then stood up and threw a grenade, which exploded directly in front of Lines. ‘For Chrissakes, somebody get me out of here,’ a partially blinded Lines cried out as he staggered towards the enemy. Ossie Kirkman went out, got Lines over his back, and carried him further down the ridge to company headquarters. Sherlock told Lines: ‘I can’t send anyone out with you; I’ve lost all my men.’ So Mucka Lines departed alone, making his way down Slippery Ridge to the Bulolo River, where a local villager helped him across.25

Back on the forward knoll, one of St John’s men had been killed and another four wounded. They included Johnny Noble, who was badly wounded in both legs. The platoon sergeant, Jamieson Gray, had gone out and, with the help of St John, brought Noble back to company headquarters. Sherlock, ever the stickler for discipline, simply asked Noble, ‘Corporal, where’s your rifle?’26

At 0740, Sherlock reported that his force was ‘holding them nicely’ but requested more ammunition. Most of the enemy troops had been making their move on Sherlock’s right flank, bypassing the ridge and heading down towards Kaisenik. However, Lines and other Australian marksmen were making it a difficult passage. Sherlock’s men still held the key ground between the Japanese and Wau. Some of the Japanese were tying bunches of kunai grass over their backs and heads as camouflage to avoid being picked off by the Australians, one of whom told Ossie Kirkman: ‘Watch the kunai grass. If it moves, shoot it.’27

Further out to the southeast, Lieutenant Lin Cameron’s platoon had been ordered to move across from Ballam’s to reinforce Sherlock. Moten’s rash decision to send the two 2/5th Battalion companies out of Wau was coming back to haunt him. At 0905, Sherlock again requested ammunition and supplies, particularly water. He also asked for native carriers to help evacuate his wounded, who were lying out in the open kunai and suffering from the rising heat. All the while, the Japanese continued to move across the high ground towards Sherlock’s right flank. Some movement was also reported on the left, along the thickly wooded gully that led down to the Bulolo River. However, Japanese operations were severely dislocated by the loss of Colonel Seki, who had been killed at the head of his battalion.28

At 0945, Sherlock reported that he was receiving small-arms fire from the Crystal Creek–Kaisenik area. The Japanese troops there had bypassed the ridge and could now easily move on Wau. Moten waited with increasing anxiety for the thirty transport flights that were scheduled to arrive that day, but to his dismay only four planes landed. He sent a frustrated plea to Port Moresby: ‘Flying conditions perfect. What about more planes.’ Unfortunately, though landing conditions at Wau were acceptable, the build-up of cloud in the mountain passes meant that no more flights could get through.29 Moten would have to face the increasingly serious threat on his doorstep with what men and supplies he had left in Wau, and that was very little. Sherlock’s stand on Wandumi Ridge now became crucial: if he could hold up the Japanese for just a day longer, the airfield might be kept in Australian hands until the weather cleared.

At 1010, Sherlock informed Moten that more troops were moving towards him from Wandumi Trig. Looking through his field glasses at the troops crossing an open kunai patch on the jungle fringe, Sherlock observed, ‘The Japs are going to get a kick up the arse—that’s Winning’s mob’. One of the commandos replied, ‘No, they’re Japs.’ Both men continued watching. As more and more troops moved across the open patch, it became disturbingly obvious that the commando was right.30

Winning had left Black Cat mine for Wandumi that morning with a mixed force of five officers and eighty-seven other ranks. Most of the men were inexperienced: even the commando platoon, under the recently arrived Lieutenant Jack Blezard, had only three of the original commandos from May 1942 among its twenty-eight men. Winning thought his men could be at Wandumi by midday provided they met no opposition. It was a vain hope. The party moved up the ridge to the Jap Track junction and followed the track down towards Wandumi, but they soon ran into stiff resistance and were forced to withdraw.31 Blezard—the son of a colonel who had fought with distinction in the First World War—was killed six days later.

At 1210, Moten ordered Captain Nick Watts to keep the supply route to Sherlock open. Watts sent six of his 2/8th Field Company engineers up onto the ridge, four of them carrying much-needed ammunition. Meanwhile, Cameron’s platoon of twenty-five men had arrived from Ballam’s to bolster Sherlock’s weakened company. One section was placed on the right, another on the left, and the third with Cameron in reserve.32

Two hours later, Sherlock sent twelve men back to Wau with some of the wounded. He was becoming concerned by the number of Japanese infiltrating down the heavily wooded gully on the left flank, and also wanted to ensure that the track down to the Bulolo River was kept open. Noble, whose legs were shattered, was carried out by two commandos, sitting on their rifles with his arms around their shoulders. They later cut some tree branches to make a rough stretcher. ‘It could be worse,’ Noble told one of them, and he displayed the two holes in his jumper where a bullet had entered and exited as it creased his stomach. After they crossed the Bulolo River at the suspension bridge at Kaisenik, a jeep carrying other wounded men took Noble aboard. It drove back to Wau through a gauntlet of Japanese infiltrators already alongside the road.33

A wounded Jack Eaton also came down off the ridge. ‘They’ve got the Bull,’ he told the other commandos. Lieutenant Tom Bullock, despite telling his men to keep their heads down, had stood up to direct 2-inch mortar fire and been fatally hit. Sherlock’s runner, Allan Smith, later observed that ‘their snipers were very hot on our Bren gunners and mortar positions, killing and wounding the operators.’34

Sherlock’s calls for help were becoming desperate. Cameron heard him bluntly tell a staff officer to ‘tell the Brigadier to get off his big . . . and if he trained his field glasses on Wandumi Trig Point he would see they [the enemy] were more than a strong fighting patrol.’35 Moten could easily look across onto Wandumi Ridge from his headquarters on the other side of the valley, so he should have been aware of the threat Sherlock faced. Observers near the airfield spotted ‘long lines of Japs like a plague of ants,’ while the Kaisenik people, having fled from their village, stood on a ridge to the south and watched as ‘they came like the rain.’ It was no mere patrol.36

By mid-afternoon, Sherlock’s men were in desperate straits. In the cloying heat of the kunai grass, the men were out of water and under growing pressure from the enemy. After crawling up through the thicker kunai on the Australians’ left flank, the Japanese launched a heavy attack and finally managed to get among St John’s forward positions around the crucial forward knoll. Ossie Kirkman was up there: ‘It gradually got thicker and thicker and then they started screaming . . . they were close then.’37 At 1455, after Sherlock sent a desperate message—‘Look like being overrun, am cut off’—Moten immediately replied, ‘Sending all help possible.’38 The dozen or so remaining men from St John’s platoon had indeed been overrun. The few survivors made it back through the commandos’ lines. From a smaller ‘pimple’ behind the knoll, John ‘Sandy’ McNaughton covered the withdrawal with his Bren gun.39

The Japanese soldiers quickly took over the captured knoll and began firing onto the now revealed positions further down the ridge. At 1510, Sherlock signalled Moten, ‘Things very hot, any help sent may be too late, one platoon overrun, countering now.’40 Knowing that the loss of the knoll exposed the other positions on the ridge, Sherlock prepared a counterattack. He rapidly gathered the remnants of St John’s men, two or three commandos, and Lyn Wilkinson’s section from Cameron’s platoon, some twenty men in all. He refused Cameron’s request to lead the attack: this was Sherlock’s moment.41 Snatching up a rifle, he dashed past his men with bayonet fixed, inspiring them to follow him. Bill Hooper later recalled that ‘It was only due to him leading us that we went back up that hill again. He led the whole way.’ The bayonet charge was too much for the Japanese on the knoll. ‘The Nips simply could not stand it . . . they all turned tail and shot back down the other side.’ Keith ‘Paddy’ Long gave covering fire with his Bren gun—quite a feat given that at Mubo, just a few weeks before, he had burned his hands so badly changing a Vickers barrel that he had to wear socks to protect the raw flesh.42

At 1525, another message came from Sherlock’s position: ‘Attack on Wandumi still in progress, trying desperately to stop them.’ Moten now realised that he would have to strip Wau in order to hold Wandumi Ridge as long as possible. He now sent seven officers and 139 men from 2/5th Battalion to the ridge. Lieutenant Rex Samson’s platoon, with twenty men, had already left for Ballam’s at 1400. Once they reached Crystal Creek they were diverted to Wandumi Ridge.43 An hour later, a composite force of another forty men from Headquarters Company followed, with orders to relieve Sherlock. The 2/5th’s 2IC, Major James Duffy, was given command of this scratch force, which included cooks, transport drivers, and even the battalion barber. With next to nothing now left in Wau, Moten sent a desperate plea to General Herring in Port Moresby: ‘Enemy attacking in force. About four hours from Wau. No reserve left. You must accelerate arrival of reinforcements.’44 When Duffy’s force reached the Bulolo River, the water was running very fast and it was not clear how the fully loaded men could cross. A stocky corporal, Bill McAuley, swam across with a rope, but it was too short to tie off. So, with the rope wrapped around one hand and his other hand grasping the tree, McAuley stood fast while the men crossed the river four at a time.45

Major Adam Muir, the 17th Brigade major, got a message to Sherlock at 1645 to say that reinforcements were on their way. The message arrived none too soon: at 1700, Sherlock reported that the ‘game is on again . . . the Japs are now engaging our positions with grenade and mortar bombs very severely.’ Muir, though not yet in touch with Sherlock, added, ‘the track above Sherlock is thick with Japs.’ At 1755, Sherlock reported, ‘Japs still pouring down past Trig Point. Having more casualties.’46

With the pressure building, Duffy’s company arrived. ‘It was a very hard trail and very slow climbing,’ Duffy noted, ‘and by the time we got up there it was getting on towards six o’clock in the afternoon.’ Sherlock put Duffy’s men on his left flank, with Cameron’s platoon on the right. McAuley, who had done such sterling work at the river crossing, lost his helmet while crawling through the kunai grass to the edge of the ridge, exposing his balding head to the setting sun. A burst of enemy machinegun fire took his life.47

In the gathering gloom, the Japanese were able to move unobserved around the flanks, and this was now the defenders’ greatest concern. Duffy, Sherlock and Cameron conferred and decided to withdraw to the other side of the Bulolo River. But at around 1900, as the men started to move down Slippery Ridge to the river, Major Muir arrived and assumed command. He told Sherlock that Moten’s orders were to hold Slippery Ridge at all costs. The ridge widened at this point, and it was by no means an ideal defensive position, so all the men could do was lie among the kunai grass a short way back from the crest of the ridge. To ensure that no infiltrating enemy troops came up the sides of the ridge and cut them off, several Australians were placed along the flanks extending down towards the river.

As night fell, St John brought his men back from the knoll. One section at a time would go to ground and provide covering fire as the others passed through, the wounded being dragged across the kunai on groundsheets, a man on each corner. Realising that the Australians had consolidated further back, Japanese troops moved around the flanks to the Bulolo River. When Sherlock made a count of his original company at nightfall, only eighteen remained. At 1823 he sent out what would be his final message to Moten: ‘Don’t think it will be long now. Close up to flank and front about 50 yards in front.’48

Through darkness and heavy mist, the Australians could see sudden bursts of light from the Japanese grenades being tossed in their direction. The first ones fell short, then cries of pain went up as they found their marks. Star shells also cast an eerie half-light across the ridge, and the Bren gunners began firing at the shadows moving towards them. Ken O’Keefe was in the forward-most position, covering the main track. His No 2 was cut up by a grenade, but O’Keefe stayed in position with his Bren so the wounded could be evacuated before he too moved back out of grenade range.49

From behind his Bren gun, Ron Beaver could see the silhouette of a soldier further up the slope throwing grenades. Beaver knew not to fire the Bren at night unless absolutely necessary, because the muzzle flash would ‘draw the crabs.’ But as the Japanese prepared to hurl another grenade, Beaver lifted the barrel to about waist height and fired three single shots at a range of barely 10 metres. The grenadier fell, screaming. Beaver then switched to automatic as more troops moved across the skyline. Thinking they might be stretcher bearers looking for the wounded man, he held his fire. Only when a pistol shot went off in front did he lower the gun and spray the kunai grass. ‘By the time I was finished,’ he recalled, ‘none of those bastards was saying a word.’50

A deluge of rain drowned out any other noise, including the sounds of Japanese creeping around the Australian positions. The downpour gave the Australians other problems. Lou Nazzari and Jack Brooker were sent back to Wau with a message, but when they got to the Bulolo River, they found it in flood. Unless a way could be found across, all the men on Wandumi Ridge would be cut off. At 0300, Duffy, whose men were still holding the positions on Slippery Ridge, told Moten that the river crossing would be perilous, if not impossible.51 Just before dawn, Sherlock moved most of the remaining men down to the river, looking for a crossing point.

The twenty to thirty men of Duffy’s rearguard had orders to remain on Slippery Ridge until 0730. As day broke, the Australians opened fire with a 2-inch mortar to delay the Japanese attack, but it wasn’t long before the Japanese returned fire with their own mortars, causing more casualties among Duffy’s men. Then, just on daylight, a line of enemy soldiers came over the crest of the ridge from the east. They were shoulder to shoulder in a straight line, with rifles and bayonets at the trail. The Australians held their fire as another line of men followed the first, rifles also at the trail. Behind them a third line came on. It was like something from a bygone era.52

Ron Mackie was one of the Bren gunners watching the Japanese troops advancing in line abreast down the ridge. As the first wave crested the hill, clearly silhouetted against the skyline, an officer yelled ‘Fire!’ and the wave just seemed to disappear. ‘They were sitting ducks!’ Mackie observed. Then the second line was targeted, and those troops also went to ground. The third line was already down and crawling forward through the kunai. Then the order came for the Australians to withdraw, and it became a race to get off the ridge and across the river unscathed. Ron Beaver heard a desperate shout: ‘Every man for himself.’53

Sherlock’s party had stayed on the ridge until the first light of dawn before he took them upstream, heading for the suspension bridge at Kaisenik. However, just before the junction of the Bulolo River with Crystal Creek, Sherlock found a large cedar log that had been felled so it lay across the river between two huge boulders. ‘Come on, boys,’ he called to his men as he straddled the log and made his way across. But as he reached the other side, the stutter of an enemy machine gun was heard. Sherlock called out, ‘Are you an Aussie?’ Another burst of fire was the reply. ‘I’ll give you Japanese, you bastards,’ Sherlock shouted. Leading the others forward, the brave captain was killed. There had been no more valiant soldier on this battlefield than Bill Sherlock: his staunch defence of Wandumi Ridge had created the chance to save Wau, and now he had been killed trying to save his men. ‘Bill Sherlock was wonderful’ Ted St John told Dudley Leggett, ‘He kept us together and inspired us all.’54 In recognition of the man whose bravery and leadership ultimately saved Wau and his own career with it, Brigadier Moten had Sherlock mentioned in despatches.

Japanese troops had been across the river since the previous afternoon. A transport driver reported seeing troops marching along the Crystal Creek road, and a scratch platoon of transport personnel was sent to defend the banks of Big Wau Creek, adjacent to the airfield. Just up the hill, at Moten’s headquarters, the staff packed up documents and hid them in a deep gully nearby. The end seemed nigh.

General Okabe’s plan had been for Seki’s II/102nd Battalion to attack along the ridge and for Shimomura’s I/102nd Battalion to head out to the south of the ridge and cross the river near Kaisenik. However, fearing that they could be fired on from Wandumi Ridge or bombed by Allied aircraft while crossing the open country in daylight, the men of Shimomura’s battalion waited until nightfall on 28 January before advancing from the cover of the jungle.55 The soldiers set off in single file following a small creek towards the Bulolo River near Kaisenik. For the last few hundred metres, they were up to their chests in water, as rain had turned the creek into a torrent. On reaching the Kaisenik area, the Japanese found Australian supplies hidden in the jungle. For the starving troops it was manna from heaven, but it also caused a serious delay in their advance on Wau. By daybreak on 29 January, Okabe’s headquarters group was still short of the suspension bridge, while the majority of Shimomura’s battalion had become hopelessly lost in the dark. They had gone too far south towards Ballam’s, and the first troops did not reach the suspension bridge until 0350; most did not arrive until daybreak.

Apart from not being in position to attack Wau that morning, Shimomura had allowed two companies of the Australian 2/5th Battalion to cross the bridge at about 0330. These companies had descended the treacherous track from Ballam’s in the darkness and rain, each man clutching the gas cape of the man in front.56 By 0430 they had reached the Crystal Creek road and were heading for Wau. Even then, the Australian companies could have been stopped by Japanese troops alongside the road. Captain Cam Bennett pushed his men hard: ‘We saw in the fast-fading night, quite a lot of people sitting on both sides of the road, but a little way back from it . . . we were well past them before they opened fire.’57 As dawn broke on 29 January, there were only seven scratch platoons defending Wau against the best part of two Japanese battalions, so the arrival of these two companies was critical.

That same morning, New Guinea Force headquarters informed Moten that everything possible would be done to get the planes into Wau that day. The Australians were very fortunate that a new air transport group had recently arrived from the United States: thirty planes would be available to fly into Wau once the weather cleared. But the blanket of cloud over the valley prevented an early start to the airlift. American fighters patrolled the sky above Wau, anxiously waiting to report a break in the fog, which came at around 0900. The sound of the transports soon filled the valley, and the first plane landed at 0915. The aircraft landed in pairs, then taxied up to the top end of the strip before turning and opening their doors to disembark the troops. The wounded were taken out on those first planes.58

Captain John May watched. It ‘was all movement now,’ he wrote, ‘the grey Douglas transports turning and facing down the runway, their sides clanging open, the unhurried speed of the soldiers disembarking and grouping ready for battle.’59 From up on the Black Cat Track, Stephen Murray-Smith also watched the troops disembark and move straight into defensive positions. ‘Life blood of green,’ he later wrote.60 There were fifty-nine flights that day. They brought 814 men to Wau: the balance of the 2/5th, and all of Lieutenant Colonel Henry Guinn’s 2/7th Battalion. Major Keith Walker, one of Guinn’s company commanders, had his hat shot off as he left the aircraft, and later wrote of ‘one of my lads being wounded and going back on the same plane to Moresby.’61 Three platoons under Walker immediately moved out to contact the Japanese troops, who were still gathering along the Crystal Creek road near Leahy’s Farm.

At 1630, under sniper fire from trees around the old slaughter yards, Walker ordered two platoons to attack Leahy’s Farm. It was soon apparent that a strong enemy force was massed in the woods behind the farm. The enemy’s machinegun and mortar fire forced the Australians back along the road, where they dug in. However, Walker’s attack had achieved its aim, preempting any planned enemy move that afternoon and keeping the Japanese at arm’s length from Wau. With two Australian battalions defending the town, the opportunity for Japanese success had now all but disappeared. So why had the Okabe Detachment not attacked that day?

After gathering on the Wau side of the suspension bridge by the early morning of 29 January, Shimomura’s battalion did advance, but it tried to get behind Wau airfield via the thickly wooded, rugged country to the south of Crystal Creek. The cover prevented any air attack, and the Japanese troops were also able to gather some food from the native gardens in the area, but neither of those benefits outweighed the loss of time. The most potent force of the Okabe Detachment spent the two most critical days of the battle wandering around southeast of Wau, with very little idea of where it was going. The condition of the men did not help. Lieutenant Yoshiro Saito wrote: ‘This was our fifteenth day we had been beaten by rain, gone without food and walked till our boots filled with blood.’62

Next morning, 30 January, two 25-pounder guns from 2/1st Field Regiment, commanded by Captain Reg Wise, were flown into Wau. While the guns were quickly assembled at the airfield, Wise joined Walker’s forward troops on the Crystal Creek road. The gunners were well practised at the task, and once assembly was completed two jeeps were used to position the guns on the airfield’s northern side. The first target was registered by 1130, just over two hours after the guns had landed.

At 1650 that afternoon, as Wise looked out from his ridge-top position down the Crystal Creek road, he could hardly believe his eyes: ‘Approx 400 Japs advanced in column of lump along the road right in front of me.’63 Wise used the phone to give the order to fire, and the first rounds fell just behind the Japanese commander, killing him and a number of his men. Wise next directed the shelling onto those attackers who had moved off the road. The shells included phosphorus smoke rounds, which set the kunai grass on fire. The effect was devastating, and any troops still advancing were soon picked off by the Australian infantry. The Japanese force then faced an air strike from six RAAF Beaufighters, which streaked over Leahy’s Farm on a strafing run. The attack had been stopped in its tracks.

It was the enemy’s last thrust for Wau, though it would take more costly fighting to evict the Japanese from the area. Meanwhile, further Australian attacks to cut the Jap Track behind Wandumi Trig Point and isolate the Okabe Detachment would prove fruitless. On 12 February, a message was received at Eighteenth Army Headquarters in Rabaul advising of the failure of the Wau operation. Two days later, the withdrawal of the Okabe Detachment remnants to Mubo, which had already been underway for three days, was officially authorised. Some 1200 of Okabe’s men did not return from Wau but Yoshiro Saito did, reaching Mubo on 21 February. ‘They washed my body in the river,’ he wrote. ‘They gave me a new shirt and fed me more porridge, then I realised I was alive.’64

Okabe, had been brought to Lae. The Japanese command announced that ‘this will send chills through our conceited enemy.’4 The failure of the Air Force to stop the convoy did indeed rock the Allied command. The Allied air commander, Lieutenant General George Kenney, responded that his airmen had ‘learned a lot and the next one will be better.’5 It was.

Okabe, had been brought to Lae. The Japanese command announced that ‘this will send chills through our conceited enemy.’4 The failure of the Air Force to stop the convoy did indeed rock the Allied command. The Allied air commander, Lieutenant General George Kenney, responded that his airmen had ‘learned a lot and the next one will be better.’5 It was.