The glassy blue surface of the Bismarck Sea shimmered beneath a cloudless sky, the cloak of morning mist gone ‘as though wiped away’ by the sun. Major General Kane Yoshihara, the Chief of Staff of the Japanese Eighteenth Army, was aboard the destroyer Tokitsukaze, part of a convoy headed for Lae. Tokitsukaze translated as ‘favourable wind,’ but on this morning the weather would not favour the Japanese. As Yoshihara discussed disembarkation procedures below decks, disaster came from above. The destroyer stopped dead in the water, ‘as though the ship had struck a rock.’ By the time he reached the deck, a bewildered Yoshihara saw that only half the convoy vessels were still afloat. From many others, smoke billowed into the sky.1

Flight Lieutenant Ron ‘Torchy’ Uren’s Beaufighter carried an extra passenger that morning: Damien Parer. He stood behind Uren, bracing his legs across the entrance well and balancing his movie camera on Uren’s head as the plane began its strafing run. Parer later told Burton Graham: ‘The first thunder of fire gives you a shock. It jars at your feet and you see the tracers lashing out ahead of you, and orange lights dance before your eyes on the grey structure of the ship.’2 Parer ‘came back literally frothing at the mouth with excitement. He had got about 5000 feet of the best material he had ever seen.’3

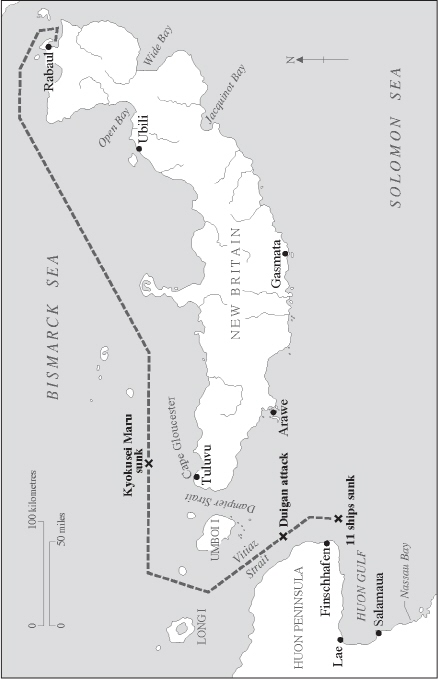

With the loss of the Papuan beachheads, Lieutenant General Hitoshi Imamura, the Japanese Eighth Area Army commander in Rabaul, planned to reinforce Lae and again threaten Wau. Emboldened by the successful convoy to Lae in January, he was now proposing that another be sent. Some 6600 army personnel, one-third of them from Lieutenant Colonel Torahei Endo’s 115th Infantry Regiment, along with tons of supplies, would be carried on eight transports. These ships would be escorted by eight destroyers and protected from above by forty naval and sixty army aircraft.4 The Eighteenth Army commander, Lieutenant General Hataz Adachi, and his staff accompanied the troops. Though aerial reconnaissance had hinted at such a convoy, Allied Intelligence was working with an ace up its sleeve: ULTRA decrypts of Japanese naval signals. On 19 February, Lieutenant Commander Rudolph Fabian’s Fleet Radio Unit in Melbourne handed General MacArthur decrypted messages that indicated there would be a convoy to Lae in early March.5

For Lieutenant General George Kenney, commander of the US Fifth Air Force, responding to this was very much a case of making do. The European theatre took priority, so he had little choice about the type and number of aircraft he could use. The planes that were available then had to be adapted for the tasks at hand, including sinking enemy shipping. Kenney was very keen on the ‘attack aviation’ concept, encompassing low-level strafing and bombing. Accordingly, he had re-equipped his only light bomber group, the Grim Reapers of the 3rd Bomb Group, with Douglas A-20 Havocs and North American B-25 Mitchells instead of dive bombers. The 3rd BG material officer, Major Paul ‘Pappy’ Gunn, had then made significant modifications to the aircraft. The Bostons were fitted with four .50-calibre guns in the nose and two 1700-litre long-range fuel tanks in the bomb bay. The lower turret and tail gun were removed from the Mitchells and four .50-calibre machine guns were installed in the nose, with another four in forward-firing gun pods mounted on the chin of the plane. Two crew members per plane were also dispensed with.6 Given that the 3rd BG would have a major role in any convoy-busting mission, the crews practised mast-level skip-bombing, in which the sides of the shipwrecked Pruth, aground on Nateara Reef off Port Moresby, were directly targeted by releasing the bomb early and letting it skip across the water into the hull.

Group Captain William ‘Bull’ Garing was the commander of RAAF No. 9 Group, responsible for all operational Australian air units in New Guinea. Kenney thought highly of Garing, and later said he was ‘active, intelligent, knew the theatre and had ideas about how to fight the Japs.’7 Garing believed a properly rehearsed plan that integrated all available aircraft was needed to target the next convoy. As soon as the convoy came within range of the Havocs and Mitchells, all available aircraft would need to concentrate and attack in quick succession, overwhelming any defences. Garing allocated the Beaufighters of Squadron Leader Brian ‘Black Jack’ Walker’s No. 30 Squadron RAAF a key role in the plan. They would strafe the bridge to disrupt each ship’s command.8

The sixteen-vessel convoy left Rabaul at 0200 on 1 March and followed a route along the northern coast of New Britain. Allied air reconnaissance was hampered by stormy weather, but one plane spotted the ships that afternoon. As night fell, a Japanese soldier on board wrote that ‘the moon has already dropped below the horizon and we sailed on with uneasiness in the darkness.’9

On 2 March, eight B-17 Flying Fortresses from the 63rd Bomb Squadron made the first attack. The three leading bombers, led by Major Ed Scott, claimed two ships sunk, one ‘breaking in half and sinking within two minutes.’10Teiyo Maru had been hit aft by two bombs, but it was not badly damaged. However, Kyokusei Maru took a direct hit, caught fire, and drew away from the convoy; it eventually sunk. Some 850 troops on board were transferred to the destroyers Asagumo and Yukikaze, both of which raced ahead of the convoy and landed the rescued men at Lae that night.11

RAAF Catalina crews took over the shadowing of the convoy that night. Geoff Watson, the radio operator on Flight Lieutenant Terry Duigan’s Catalina, transmitted the vital radio message that the convoy was heading south through the Vitiaz Strait towards Lae. Duigan dropped bombs on one of the escorting destroyers and watched as ‘the bursts came marching up the middle of the wake and the last one shaved the stern.’ Unfortunately, navigator ‘Bob’ Burne had entered the ship as ‘stationary’ in the bomb sight. After a mission lasting more than fifteen hours, Duigan’s aircraft returned to Cairns.12

Torpedo-carrying Beauforts from RAAF No. 100 Squadron left Milne Bay before dawn on 3 March. Despite the heavy weather, two aircraft launched torpedo attacks on the convoy, but neither was successful.13 However, this action would lead the Japanese captains to misjudge the next attack, by Beaufighters.

The day dawned clear over Port Moresby, and a growing noise reverberated from the surrounding ranges. As planned, all available aircraft gathered at staggered altitudes over Cape Ward Hunt, approximately halfway to the target area, at 0930. Though he had been grounded by the medical officer, ‘Black Jack’ Walker accompanied the Lightning escorts in his Beaufighter to watch over the battle. Sergeant Dave Beasley, the observer in Pilot Officer George Drury’s Beaufighter, noted that ‘the sky looked jammed full of planes.’14 Thirteen B-17s made the first attack. One was shot down by enemy fighters, which were then engaged by the Lightning escorts. Three of these were also lost, but they had helped divert the enemy fighters from the main attack force, which was now racing in at low level.15

The Beaufighters came in just above the waves. With four 20-mm Hispano cannons in the nose and six .303 Browning machine guns in the wings, they were formidable opponents. Each Beaufighter picked its own target. Expecting another torpedo attack, the ship captains misread the threat and turned their bows to the attackers, thus allowing the entire length of their vessel to be strafed. The RAAF planes kept strict radio silence, but when the excitable Americans got over the convoy, they had a lot to say. George Drury overheard one: ‘Oh, baby, look at those boys down there, let’s go get ’em.’ The American pilots also got to the target area ahead of time, so their bombs were falling around the Beaufighters as they went in.16

Flight Lieutenant Dick Roe was strafing a vessel at masthead height when a bomb from a Mitchell exploded on its deck. The debris dented his plane. Flight Lieutenant George Gibson had a similar experience when a bomb exploded amidships as he flew between a vessel’s masts.17 Sergeant Moss Morgan had just opened fire on a transport when a Mitchell passed in front of his Beaufighter and dropped two 500-pound bombs. The first hit the ship, and Morgan watched as ‘the whole thing blew up right in front of me.’ The second bomb skipped right over the top. Morgan observed that ‘it seemed a nasty experience to see a 500 lb bomb whistling past your ear.’18

Flying only 10 metres above the waves, George Drury managed to line up three of the transports in a row and made his run on the first of them. ‘It was the start of five minutes of mayhem and pumping adrenaline,’ he said. He was attacking the ships from the side, as he was moving too fast to target them beam-on. When his four cannons and six machine guns opened fire, the recoil was tremendous, slowing the plane considerably. Then a Mitchell came in over a ship at masthead height and landed a bomb on the stern, spreading flame and debris in all directions. As Drury pulled up for a run at the second freighter, he realised that the terrific reverberation from his guns had blown the globe in his gun sight out of alignment. However, he was able to aim his tracers—one for every four bullets—at the ship’s waterline, then ease up the nose to fire at the bridge. He had to bank his plane at the end of his strafing run so as to fly between the masts, and could see fires starting as he passed overhead. As Drury pulled his plane up for the run on the third freighter, his observer, Dave Beasley, shouted, ‘Bandit, dive left!’ Drury headed off close to the waves, jinking the aircraft about by walking the rudder from side to side.19

The Beaufighter of Flying Officer Bob Brazenor and Sergeant Fred Anderson strafed a 7000-ton transport from stern to bow. Then, as Brazenor attacked a second vessel, he was jumped by a Zero. Anderson could see the enemy plane coming down at them from above, the gun ports smoking. He yelled out to warn Brazenor, who, like Drury, stayed low and headed out of the battle, dragging the Zero with him.20 In another Beaufighter, Sergeants Ron Downing and Danny Box had their port engine and elevator disabled by anti-aircraft fire. Despite being wounded, Downing managed to crash land the aircraft at the forward airstrip at Popondetta.21 The Beaufighters were sturdy steeds, and, as Garing had anticipated, their strafing severely disrupted the transports’ commands, as well as their anti-aircraft defences. They also distracted the Japanese fighters, giving the Mitchells and Havocs an easier passage.

As the Beaufighters went in, thirteen Mitchells bombed from medium altitude before Major Ed Larner’s twelve Mitchell strafers came in at sea level. Larner told his men, ‘I’m making a run on that lead cruiser. You guys pick out your own targets.’ Larner went in broadside, strafing first and then crashing two delayed-action bombs into the side of the destroyer Shirayuki. One of the bombs hit the aft turret and the magazine exploded, blowing the stern off the ship. On board the Kembu Maru, Tagayasu Kawachida watched the well coordinated attack on Shirayuki. He saw the first plane to attack, a Beaufighter, come from the port side and strafe the ship with machinegun fire. As the destroyer took evasive action, altering course and zig-zagging, a second aircraft attacked, planting its bombs squarely amidships. In the back of Drury’s Beaufighter, Dave Beasley watched as a bomb ‘blew the arse right off ’ the destroyer. The low-level attacks were devastating: of thirty-seven bombs dropped by Larner’s Mitchells, seventeen were claimed as direct hits. The Havocs had similar results.22

The destroyer Arashio was hit and collided with the abandoned naval supply ship Nojima, which had been disabled during the initial attacks. Masuda Reiji, who was working in the Arashio engine room, observed: ‘Our bridge was hit by two 500-pound bombs. Nobody could have survived. . . . Somehow those of us down in the engine room were spared.’ The chief engineer and Reiji took over the ship, which was still able to make five or six knots. A second attack caused further damage, but eight men continued to steer the ‘ship of horrors.’23 Aboard Tokitsukaze, which was hit by the low-level bombers at around 1010, the Eighteenth Army headquarters staff, including Yoshihara, hurriedly abandoned ship. They transferred to Yukikaze, which had returned from Lae after its earlier rescue mission.24

The low-flying Mitchells soon found Kembu Maru. ‘Now they turn their attention to a small cargo vessel, perhaps a 500-tonner,’ Burton Graham wrote. ‘One hit is made right off. It is too easy. Another hit on the port side. She lumbers about in the foam and then catches fire.’25 The hundreds of fuel drums on board soon exploded and the ship sank within five minutes. Like the other six transports, Shinai Maru was attacked within that first deadly fifteen minutes. A bomb hit amidships, setting the vessel ablaze, and it sank an hour later.26 On Oigawa Maru, Second Lieutenant Kiyoshi Nishio watched as ‘a cloud of aircraft appeared.’ The ship sped up, but was hit just aft of amidships by two bombs and immediately caught fire. The engine room had been blasted, and the powerless vessel stopped dead in the water.27Taimei Maru was bombed five times. Its lifeboats were smashed, forcing the troops and crew to jump overboard.28 On Teiyo Maru, the helpless Japanese soldiers watched the low-level bombers approach from three directions before one bomb struck the top deck and a second stopped the engine. The blazing ship was soon abandoned.29 By 1015, all seven of the Japanese transports were sinking.30

Back at Port Moresby, as the second series of air attacks began, William Travis wrote: ‘They’re going out; bombing; returning; loading up again . . . the crews are drawing straws and fighting to see who gets to go out next!’31 That afternoon, Squadron Leader Charles Learmonth led a strike by five RAAF No. 22 Squadron Bostons which found the destroyer Asashio still afloat. The Bostons attacked it in pairs, and despite a heavy anti-aircraft barrage, two of their bombs hit Asashio amidships, sealing its fate.32

The four surviving destroyers withdrew up the Vitiaz Strait and gathered east of Long Island. There they were joined by the destroyer Hatsuyuki, which refuelled them and, together with the damaged Uranami, returned 2700 survivors to Rabaul. The three other destroyers, with minimal crews, refuelled and headed back to assist other survivors.33 Over the course of the battle, the destroyers rescued some 3800 men.34

Next day, there was another, less palatable mission for the Beaufighters. The air crews were ordered to strafe the survivors as they clung to their overloaded lifeboats. It was unpopular work. However, it did not violate the rules of war: the Japanese soldiers had not surrendered and would fight in the front lines if they reached land. Most of the lifeboats drifted further south and ended up in Allied territory. Documents were captured on Goodenough Island that provided a very accurate picture of enemy deployments. Captain Aubrey McWatters noted that ‘We gradually learned [a patrol from the 47th Battalion] had picked up the stud book and all the box and dice, etc.’35 It was estimated that 352 survivors were killed as a result of strafing by aircraft and attacks by patrol boats.36

General MacArthur rightly commended his airmen. ‘It cannot fail to go down in history as one of the most complete and annihilating combats of all time,’ he said of the Bismarck Sea battle. ‘My pride and satisfaction in you is boundless.’ General Kenney, who was on his way to America to argue for more aircraft, added: ‘Tell the whole gang that I am so proud of them I am about to blow a fuze.’37 The acting New Guinea Force commander, Lieutenant General Iven Mackay, put the victory into perspective, saying, ‘You have inflicted more casualties on the Japanese in three days than we could do in three months.’38

MacArthur issued a communiqué estimating that Japanese Army casualties numbered 15,000, all of whom had perished. Australian analysis put total Japanese personnel losses at 6000–7000, less than half MacArthur’s figure, with 3000–4000 survivors. MacArthur declared these new figures ‘glaringly wrong, I cannot fail to take exception to them.’ He also continued to insist that the convoy contained twenty-two vessels: twelve transports and ten destroyers.39 Damien Parer observed: ‘The war’s a phoney MacArthur-made one. He’s blown up a big balloon full of bullshit and some one’ll prick it one day.’40 After the war, it was established that the ships carried a total of 8740 personnel: 2130 naval personnel and 6610 troops. Of these, 2890 men were lost, 2450 of them army personnel and marines.41

Lieutenant Masamichi Kitamoto watched survivors come ashore at Tuluvu, on the northwestern edge of New Britain. ‘One group was made up of seriously injured men whose faces were covered black with oil. Their eyes were all glassy and deeply sunk into their faces. All were jittery and full of fear as if they were seeing a horrible dream . . . A pitiful scene of a vanquished and defeated army.’42

After the Bismarck Sea battle, the Allies kept up the pressure on Lae and Salamaua. During March, Learmonth’s Bostons flew seventy-two sorties over Salamaua, six of them on 18 March. On that day, Flight Lieutenant Bill Newton was piloting Boston A28-3, with Flight Sergeant John Lyon as his navigator and Sergeant Basil Eastwood as the rear gunner. During a similar attack two days earlier, Newton had taken four hits from anti-aircraft fire, but despite damage to his plane’s wings, engine and fuel tank, he had managed to return to Ward’s Drome at Port Moresby.43

The Bostons came in across the ridges west of Salamaua, dropped their bombs on the airfield, then turned to strafe the adjacent buildings. After Newton bombed a building near an anti-aircraft battery, his aircraft’s fuel tank was hit by a cannon shell, forcing him to ditch the burning plane in the ocean off Salamaua.44 Eastwood was killed; Newton and Lyon swam to shore and were captured. The Japanese considered Newton ‘a person of importance, possessing considerable rank and ability.’ Newton and Lyon told their interrogators that they were only attacking the store buildings, not Japanese personnel, and stressed that, ‘We are fighting to preserve the Australian mainland.’ On the afternoon of 29 March, having been returned to Salamaua, Newton was told he would be beheaded. Newton looked at the sword and said, ‘One,’ meaning that it should be done in one stroke. Newton’s fate was not uncommon for captured Allied airmen.45 In Lae, navigator Lyon was bayoneted to death. Newton had been flying his 52nd operational mission when his plane was shot down; most of these missions were under enemy fire. For his valour, he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

In the ranges behind Finschhafen, Captain Lloyd Pursehouse had observed the Bismarck Sea battle from an observation post overlooking the Vitiaz Strait. The quiet, red-headed Coastwatcher had been a patrol officer with the Australian Administration before the war and knew the country well. Familiar with the land and the local people, Pursehouse radioed back vital information on Japanese air and naval movements to Port Moresby. He was one of many Australian Coastwatchers who patrolled the shores of New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, providing the Allied commanders with a priceless advantage over the Japanese. Lieutenant Ken McColl, who had been serving as a Coastwatcher on one of the islands to the north, joined Pursehouse at the end of 1942. After the demise of the merchant ship convoys, Pursehouse and McColl were meant to play a vital role in preventing coastal barges from reaching Lae.

On 3 April, a month after the Bismarck Sea battle, McColl headed down the track to his and Pursehouse’s forward observation post, leaving Purse-house resting at a hut further back in the jungle. McColl was surprised by a Japanese patrol but managed to dash off into the jungle. When he returned to the hut, the enemy troops had been and gone; Pursehouse was not there. The Japanese had surrounded the hut and fired into it, but Pursehouse had heard them coming and taken off. The two men met up the next day and reached a rear camp, from where they reported to Moresby by radio. Clearly compromised, they were ordered to withdraw across the Markham Valley to Bena Bena. After sixteen months of sterling service, Pursehouse was to be relieved.46