12

‘Hell, what chaps these are’

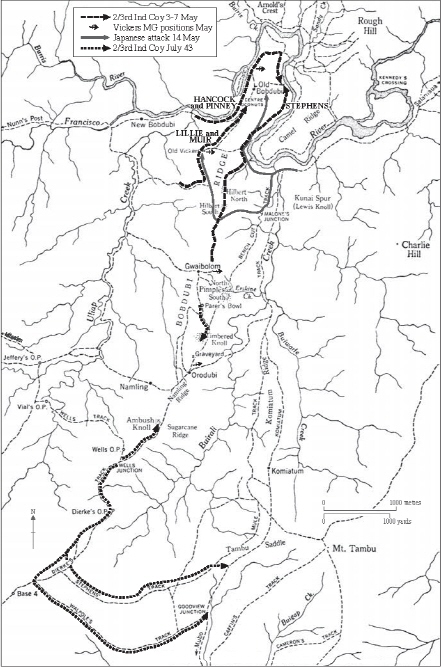

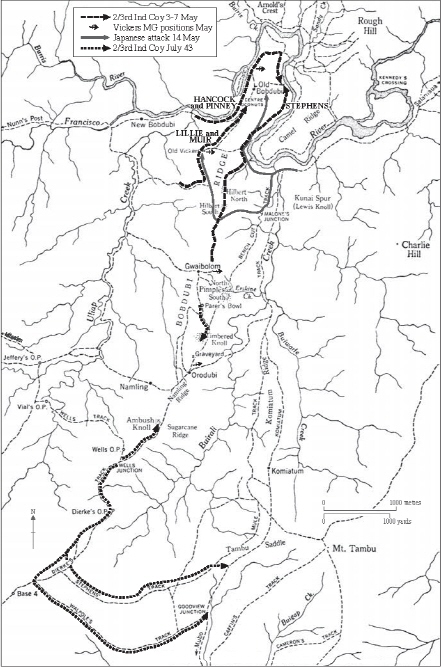

Bobdubi Ridge

February to July 1943

He ‘would make your blood go cold at his superlative courage and cool savagery,’ one of his fellow officers said.1 Major George Warfe had already made a name for himself in the Middle East, but in New Guinea, he and his 2/3rd Independent Company would attain legendary status. Once, as his men harried the Japanese retreat along the Jap Track from Wau, Warfe came across a group of Japanese soldiers preparing their dinner, and delayed his attack until the food was cooked so his own men could have a feed afterwards. Another time, Warfe waited at the top of a steep climb for two Japanese soldiers, who reached the crest exhausted. He sat down between them, and when they realised he was not one of them, shot one soldier while a fellow commando dispatched the other.2

Warfe’s company had flown into Wau on 31 January 1943, at the height of the Japanese attack. Despite early setbacks, by the time they went back across the Jap Track from Wau on the heels of the retreating Japanese, his men had become very astute jungle fighters. Peter Pinney, who went across the track as a signaller with Lieutenant John Lewin’s platoon, illicitly kept a diary in an ‘attempt to record one slender thread of truth.’ Of tailing the Japanese over the Jap Track, he wrote: ‘Followed a muddy ridge churned up by booted feet, past a steady litter of bodies and equipment, discarded weapons . . . the trail leads over the top of a tight-meshed web of roots between some fairly big timber and a lot of lesser trees bearded with moss and lichen, permanently dripping wet.’ When some Japanese tried to waylay Warfe’s commandos, Pinney wrote, ‘the blokes up front blasted their way through the ambush by sheer firepower . . . Our mob outclassed them.’3

Almost out of food and needing to care for the wounded, Lewin and his platoon returned to Wau. When Brigadier Murray Moten asked, ‘Why did you come back?’ Lewin replied, ‘I had sick and wounded.’ ‘You should have left them,’ Moten told him. ‘I’ll never leave them,’ Lewin said. The lieutenant served with distinction as a front-line commando platoon commander, a captain’s posting, for a further seven months during the Salamaua campaign, yet was not promoted.4 He never left a man behind.

On 28 February, Warfe’s company was ordered back to Wau and thence to the Bulolo Valley. The men were keener to keep going towards Mubo and Salamaua. ‘For chrissakes,’ Pinney wrote, ‘we slogged our way up that rotten trail to get as far as this: we’ve paid our entrance fee, we’re all here armed and provisioned and in pretty good nick, what the hell’s the point of going back?’5

The men of the 2/3rd Independent Company would get to threaten Salamaua, but from a different direction. General Blamey had told Moten, ‘I would be glad if you would give consideration to the question of inflicting a severe blow on the enemy in the Salamaua area.’6 That directive would push the Australian Army into the rugged jungle terrain that guarded Salamaua from any approach by land.

On 9 March Warfe led two of his three platoons across the daunting Double Mountain crossing to Missim, west of Salamaua. Keith Myers recalled, ‘It was seven or eight false crests on Double Mountain, mud up to your knees, all the troops walking over it.’ Brian Walpole said, ‘You had to use both hands to get up there and I can remember you would get up and then you slide back ten or twelve feet and . . . you’d almost feel like crying.’ Later that month, a party of US Army personnel was ‘compelled to give up owing to sheer physical exhaustion.’7

Although Warfe moved two platoons to Missim, he had major supply problems because the tenuous track across Double Mountain broke down under heavy rains. The carriers arrived at Pilimung exhausted, and air-dropping could deliver only a fraction of the supplies they needed. Though his immediate task was to establish a firm base at Missim and set up an observation post overlooking Salamaua, Warfe wanted more.

On 1 May, Warfe submitted his plan for future operations to Major General Stan Savige, whose Australian 3rd Division headquarters had now taken command of the Salamaua theatre. Warfe stressed the need to bring a speedy conclusion to such operations: otherwise, malaria, typhus and dysentery would rapidly erode his unit strength.8 Savige did not support the extensive operations that Warfe was proposing, but he did sanction action against the northern end of Bobdubi Ridge to take some of the pressure off Mubo, where the Japanese defence was holding firm. However, Savige would allow Warfe to use only a single platoon for the operation.

The northern end of Bobdubi Ridge rose like a fortress from the hinterland west of Salamaua, surrounded on three sides by its moat, the Francisco River. On 27 April, Peter Pinney led a three-man patrol to observe and map the Japanese positions there. From the riverbank he watched the approach of five enemy soldiers, one of whom lay down behind a light machine gun while another knelt alongside. Pinney ‘aimed square at the middle of his broad back and squeezed the trigger. He pitched on his face, and the game was on . . . The LMG gunner hesitated. Then of all things began getting up to take his gun behind cover. He didn’t make it, I shot him.’ Pinney and his two mates scooted back up the track to Missim. ‘We were white-haired boys,’ Pinney wrote. ‘Our maps were the first authoritative, dinky-die on the spot information they had had.’9

Captain Wally Meares’s platoon would make the attack on Bobdubi Ridge, backed up by four Vickers machine guns, strictly non-regulation issue and operated by the transport section. Lieutenant Ken Stephens and his section would move north down the Bench Cut Track from Namling along the eastern side of Bobdubi Ridge to interdict any Japanese moves on or off the ridge. At the same time, Lieutenant John Lillie would take his section around the northern end of the ridge to threaten the enemy’s rear. Both moves were designed to sow panic among the defenders on the ridge. That way, when Meares sent Corporal Andrew ‘Bonnie’ Muir’s section along the ridge top, the defence would break.

Bobdubi Ridge area: 2/3rd Ind Coy operations

Meares’ men gathered on the river flats in the shadow of Bobdubi Ridge early on 3 May, and Peter Pinney pointed out the locations on the ridge that he had chosen for the Vickers guns. There were three Japanese positions along the northern end of the ridge, each centred on a clump of coconut trees, named South, Centre and North Coconuts. Fire from South Coconuts stopped Lillie’s section, which then acted in a holding role while Stephens’ and Muir’s sections manoeuvred around the Japanese position. The Japanese withdrew to Centre Coconuts.

Pinney went in first and located the enemy position overlooking the river flats. ‘I crawled ten yards to the edge of the knoll and made out quivering bushes and LMG smoke below me,’ he wrote, ‘and lobbed a grenade on top of it and took off crabwise on my belly like a gutshot bluetongue.’ He and George Tropman then guided Muir’s section up to South Coconuts as dusk fell. Pinney wrote, ‘The Nips seemed to know something was going on and opened fire, but they were firing in the wrong direction.’10 Muir also established a position on a dominating feature further back along the ridge which would become known as Old Vickers. From here a Vickers gun could be fired onto the Coconuts and also the Komiatum Track, the Japanese supply route between Salamaua and Mubo.

Pinney was caught up in the battle. ‘The Vickers opened up with long strong bursts with ricochets and general hell flying everywhere . . . we hugged that dirt. The Nips were throwing everything everywhere: heavy and light machineguns . . . light mortars, grenade launchers.’ However, when Lillie’s section attacked, it was fired on from South Coconuts: after the commandos pulled back to allow the Vickers to fire, the Japanese had boldly reoccupied the position. Pinney watched Lillie’s forward scouts move up. ‘George Head and Tassie [Ossie McDiarmid] crept off to have a looksee, moving very carefully and slowly… and after a few minutes there was a long burst of Jap fire. George came back alone. Tassie was dead . . . we discreetly withdrew.’11

On 5 May, Lieutenant ‘Jock’ Erskine’s engineer section, moving south along Bobdubi Ridge, opened long-range Bren gun fire on sixty enemy troops moving back from Mubo along Komiatum Track. The first fire left five Japanese dead on the track and fifteen minutes later, another seven were killed. That same day, Savige told Warfe that another large group of enemy troops was expected to move to Mubo. With Meares’ platoon occupied, Warfe grabbed the medical officer, Captain Fred Street, some riflemen and a Vickers gun. This was positioned below Gwaibolom, midway between Muir’s and Erskine’s sections. From here Warfe could see a 250-metre length of the Komiatum Track at a range of 800 metres. When fifty enemy troops moved up the track towards Mubo, a 250-round belt was fired, killing about fifteen Japanese and confusing the rest, who fired wildly at what they thought was an ambush. Later that afternoon, another eighty enemy troops were engaged.12 Damien Parer, who later met Doc Street, wrote of him: ‘He would rather have a gun than a hypodermic needle.’13

On 6 May, Pinney led Captain Bob Hancock around the northern end of Bobdubi Ridge. ‘There was a bit of a pad, rough and a bit dicey in parts, squeezing along the bank; no scrub bashing. We found the supply trail which feeds Bobdubi, too. Nice piece of information: a sneaky route for an ambushing patrol.’14 Having found Stephens’ section, Hancock deployed the men to better cover the likely route of any Japanese approach. ‘During this time the recce work by Private Pinney was outstanding,’ Warfe later noted. Keith Myers put it another way: ‘Pinney moved like a ghost.’15

On the morning of 7 May, Bonnie Muir led his section to Centre Coconuts, only to find the enemy troops gone. However, an hour later the Japanese returned and made three counterattacks, each one repulsed. When a fourth attack with mortar support succeeded, Muir withdrew his battered section. Brian Walpole was there: ‘I came face to face with this bloody Jap. We were both surprised. I pointed, he pointed, he was quicker than I am. Went to fire, the bloody thing jammed and he started to run away. So, well that’s not so bad, so I pulled out the Colt and shot him.’16

That afternoon, Hancock led Lieutenant Gordon Leviston’s section up onto North Coconuts. This put further pressure on the last enemy foothold at Centre Coconuts, where eighteen men were now surrounded on four sides by Leviston, Lillie, Muir and Stephens. Lieutenant Toshio Gunji, who commanded the defenders, estimated that he was being attacked by 100 enemy troops. The Japanese moved quickly to reinforce Gunji, and by dawn the next day sixty enemy soldiers were moving up onto the ridge. Now Stephens’ section came into play, executing a perfect ambush that left twenty Japanese dead on the track and the rest fleeing back to Salamaua.17

Though denied reinforcement and supplies, Gunji’s men continued to hold out—until the wily Warfe organised a night attack with accompanying flares and amplified screaming. Nerves got the better of the Japanese, and next morning the position was found vacant. ‘The Major came in tonight pleased as Punch,’ Pinney wrote of Warfe. Now in full control of the ridge, Warfe’s four Vickers guns flayed the Japanese columns moving to and from Mubo along the track across Komiatum Ridge. When the Japanese figured out where the Vickers guns were and began to shell them, Warfe would have them moved: ‘Punch and piss off,’ as Pinney put it.18

The loss of Bobdubi Ridge and the interdiction of the Mubo supply line caused great consternation at the Lae headquarters of Lieutenant General Hidemitsu Nakano, and reinforcements were sent to regain control. A combined force under Lieutenant Takeshi Ogawa arrived at the Komiatum Track junction at dawn on 12 May and gathered up Gunji’s remaining men, who were to guide them across the treacherous terrain onto the ridge.19 That morning the Vickers guns killed another thirty on the track to Mubo. They repeated the dose the following day, even as a burial party was still busy with the first lot.20 Ogawa’s mission to retake Bobdubi Ridge suddenly became very urgent.

When Ogawa attacked, the Vickers gun on North Coconuts stopped his men in their tracks. The Japanese responded with heavy artillery and mortar fire, and the fighting went on all afternoon before more enemy reinforcements arrived from Salamaua.21 Early on 14 May, Warfe was at his headquarters down on the river flats, ‘cleaning up and getting ready for further mischief,’ when the attack began. Ogawa had moved his men around the flank, ascending Bobdubi Ridge unobserved and overrunning Meares’ position from the south. Meares was about to tuck into some fresh fish when the enemy rushed forward, but he and his men got away. Ogawa now positioned two of his platoons on Old Vickers and the third on a knoll further south. Jock Erskine’s section ran into this platoon, and his section was forced to pull back along the ridge towards Namling.22

Having recaptured Old Vickers, Ogawa now went after the Coconuts, driving the commandos off the ridge and back across the kunda (cane) bridge over the Francisco River. All men were across by 2030, and the explosions behind them signalled that the booby traps laid by Lieutenant Stan Jeffery’s engineers had ‘caused the Japs no end of excitement.’23 One of those injured was Major General  Okabe, whose Okabe Detachment had undertaken the Wau operation. He got a bullet through his right foot after he stepped on one of Jeffery’s nasty toys. As ‘Vin’ Maguire noted, ‘We had all sorts of gadgets.’24

Okabe, whose Okabe Detachment had undertaken the Wau operation. He got a bullet through his right foot after he stepped on one of Jeffery’s nasty toys. As ‘Vin’ Maguire noted, ‘We had all sorts of gadgets.’24

That night, Savige warned Warfe that Japanese aircraft had landed at Lae and that he could expect attention from them the next day. Peter Pinney watched as they swooped in for the attack. ‘Back came the planes. Judas wept, we’d had the Richard now: we were trapped in the open . . . they could riddle us, like knocking chooks off a perch. But no—they strafed Bobdubi village, blew up our former HQ.’25 Warfe later wrote, ‘We were hilarious when the Japs bombed their own territory.’26

General Savige later wrote of Warfe’s company: ‘It was their pre-campaign testing which enabled me to tackle the Salamaua campaign confidently. I tested my appreciation by letting Warfe onto Bobdubi Ridge.’ Warfe’s men, he added, ‘prowled their section of the jungle like hungry tigers.’27

After weeks in the jungle, Warfe’s commandos were filthy and most carried beards. So when Keith Myers and Jim Buckley saw a chap coming up the track from Missim dressed in a safari-type outfit and carrying a large camera, Myers turned to his mate and said, ‘My God, what’s this?’ Buckley replied, ‘Jesus, what have we got here . . . look at this bloody dickhead, where do you think he’s going, a fancy dress ball or something.’ The chap nodded hello as he made his way past. ‘G’day, fellas, how are you?’ ‘Not bad, thanks,’ Myers replied, but Buckley couldn’t resist a jibe: ‘What the bloody hell are you supposed to be, mate?’ ‘My name is Damien Parer.’28

After resigning from his job as an official war photographer, Parer had returned to the front. Frustrated with the pettiness of the bureaucrats and with the inadequacy of his allowances, he had given three months’ notice on 25 May. ‘They can go to hell!’ he wrote. But before he moved on, he was determined to record the life of a front-line infantry section; the beckoning finger of the Salamaua peninsula had tempted him back. By flying to Wau, he had avoided the Bulldog Track, but Double Mountain still lay ahead. ‘How the hell the native carriers can carry stretcher cases back over that slippery, steep rooty track I can’t imagine,’ Parer wrote of it. ‘This stretch is worse than any I encountered on the Kokoda Trail. Over there eight natives needed on a stretcher—sixteen here.’29 A few weeks later, Keith Myers saw Parer at Namling and told him, ‘I’m sorry for what my mate said.’ Parer replied, ‘Don’t worry about it, I can understand.’ When Myers asked him what he was doing there, Parer replied, ‘Well, I was sent here to take photos of the militia in action . . . I’ve been there a week and they haven’t moved . . . I came over to the fighting men.’30

In early July, after the 58/59th Battalion had taken over at the north end of Bobdubi Ridge, Warfe’s company was moved to the southern end. This was part of Operation Doublet, a plan to unhinge the Japanese defences in front of Salamaua. It had three main parts: the 58/59th would assault the north and centre sectors of Bobdubi Ridge; an American regiment would be landed at Nassau Bay on the coast; and Moten’s 17th Brigade would make a major attack on Mubo. Warfe’s role was to establish a strong blocking position at Goodview Junction ‘to prevent the escape northwards of enemy forces in the Mubo area.’31 He would provide the anvil for the hammer blow against Mubo.

Warfe moved down from Missim with two of his three platoons, accompanied by 200 native carriers. From Namling, eighty-five carriers would carry the supplies, two of Warfe’s beloved Vickers guns, and a 3-inch mortar to near Goodview.32 But the 58/59th failed to secure the Orodubi area on Warfe’s left flank, giving the Japanese a clear view of the track to Goodview. On the morning of 6 July, the carrier line was ambushed. Peter Pinney, who had passed through before the Japanese started firing, wrote: ‘Fierce fighting broke out behind us, and stopped . . . A Platoon had been ambushed.’33 Fresh Japanese troops had sprung the ambush as the Australians climbed a steep ridge-top crag later known as Ambush Knoll.

That night, Brigadier Heathcote ‘Tack’ Hammer ordered Warfe to leave a small force to secure the track and continue to Goodview to carry out his original mission.34 Warfe detailed eight men to hold the position at Wells Junction, bluntly informing them that ‘if the Japs are here when we come back, you better be dead or you’ll be court martialled.’35 Warfe clearly had his difficulties. ‘Hammer was constantly on the phone, the rain was incessant and my temperature was 104 degrees,’ he later wrote. ‘We were all hungry and confusion reigned supreme.’36

Two of Warfe’s platoons would attack Goodview Junction on 8 July. Wally Meares’ platoon would use Stephens’ Track, and Captain John Winterflood’s men would use the recently blazed Walpole’s Track. On 7 July, Meares’s men moved east along Stephens’ Track and settled for the night at Stephens Hut, about 400 metres west of Goodview Junction. ‘We bedded down in pouring rain after a frugal tea, on sodden ground, in darkness, half an hour from the Komiatum track,’ Pinney wrote. ‘Rain poured down all night. We got up at 4.30 and grateful to bring this travesty of rest to an end, packed drenched things in saturated packs, shaking and shivering with cold.’37

Winterflood’s men moved off at dawn along Walpole’s Track. ‘It’s very steep,’ Norm Bear recalled. ‘To get along there it was single file. You couldn’t have a broad frontal attack.’ Fred Taylor led the men off the track and around the left flank of the Japanese blocking position, the sound of their approach deadened by the rain. As the Japanese guard dozed, Taylor slipped a grenade into his weapon pit. The explosion brought the rest of the enemy squad to their feet, to be met by Australian gunfire. Once again, Taylor was to the fore, charging in with his Tommy gun and capturing the position, which overlooked the track junction. ‘Les’ Poulson fired single shots from his Bren at a party of Japanese who were setting up a machine gun. ‘He killed seven of them before they woke up to the fact that they shouldn’t be trying to do it,’ Bear recalled.38

That afternoon, the Japanese counterattacked Winterflood’s position from both flanks. ‘Robbie’ Roberts noted that ‘their aim was too high, as their bullets were hitting the trees above us and showering us with twigs and leaves.’ Winterflood’s men took a toll, but the platoon’s position in a bed of tree roots was untenable, and the men had to withdraw 300 metres up Walpole’s Track. ‘We didn’t have any support,’ Norm Bear said. ‘They had trench mortars. They had a mountain gun. They had half a regiment. We were totally undermanned, not in the race.’ Bear was wounded. ‘I got hit with a bloody bit of mortar shell . . . threw me to buggery getting whacked against a tree and put a hole in my bum, but I was OK. We got out.’ Not everyone did. Out on the flank, Tommy Kidd and ‘Pancho’ Stait were left behind. Next morning, after Stait had taken apart his Tommy gun to clean it, he heard enemy voices on top of the hill. After warning Kidd, he quickly reassembled his gun and the two men took off into the scrub, chased by enemy grenades. They rejoined the unit two days later.39

To the left of Winterflood, Wally Meares’ platoon had moved up Stephens’ Track before dawn. ‘We adopted a fast pace,’ Ron Garland wrote, ‘as I wished to hit the Japs as early as possible.’ However, when Garland’s section reached the kunai clearing that marked the Mule Track junction, the Japanese machinegunners were waiting. Pinney wrote: ‘Thirty yards away was the bench-cut Komiatum track we’d heard so much about. The forward scouts and first few of the patrol darted across it safely and vanished in a jungled gulley, then suddenly an LMG opened up and swept the track with a long burst.’ The other sections bypassed Garland to the right and reached the main Komiatum Track, only to find a strong enemy position covering its junction with the Mule Track and Stephens’ Track. It would not fall until 8 August, one month later. Pinney wrote: ‘We were still flopping round like a bunch of chooks in a dust bath, selecting defensive positions where we wouldn’t shoot each others’ heads off, when Troppy [George Tropman] saw the leader of a mob coming. Seventy Japs passed us less than ten yards off, happily yodelling to each other like “Hi-ho” in Snow White. And somewhere close by a few hundred yards off, their mates with the LMG are being murdered by rascally intruders. Strange animals, these Nips.’40

Meares now attacked from the east. ‘We couldn’t tell if the Japs had been reinforced, or how the patrol was doing,’ Pinney wrote, ‘so we began to circle around towards them . . . we attacked three times, and three times we withdrew. It’s not our forte, belting in frontal assault through fixed defences, and I don’t know why we bothered to try . . . It was confused fighting in too much cover where hardly anyone, once they went to ground, could see anyone else, and anyone who poked his head up copped a concentrate of fire.’41 With Japanese reinforcements moving up, Meares withdrew to a blocking position on Stephens’ Track at dusk.

Later that day, Brigadier Hammer signalled Warfe: ‘Max. no. personnel possible MUST be concentrated in fight for Komiatum Track. Possession must be gained 9 July for success of ops.’42 Warfe stripped his rear areas and sent the men to Goodview Junction, where he was now fighting a full-blown infantry action better suited to a battalion. Signallers, cooks and carrier escorts were brought forward, giving Warfe 102 men on Stephens’ Track and forty-six at Goodview Junction. At Stephens’ Track junction, Pinney wrote, ‘Each of us put in two hours on listening posts through the night, and slept in pelting rain. You couldn’t have seen a Jap admiral at three paces.’43

The next day, 9 July, started well for Pinney. ‘The everlasting rain cleared, and early morning was ablaze with glorious sunlight, steam drying the patch of open space we own. We stayed where we were, presumably an anchor point to secure the escape route out of this melange of confusion.’44 That morning, Winterflood’s platoon put in another attack. ‘Because it’s a narrow defile,’ Norm Bear recalled, ‘naturally the Japanese have got a machine gun set up on fixed lines, and the first bloke to shove his nose around the corner was killed, Les Prentice, and the whole exercise was called off, recognised of course by George [Warfe] that it was just a wasteful, stupid exercise. And it was.’45 On 14 July, the 2/5th Battalion, after advancing from Mubo, took over Warfe’s blocking position at Goodview.

Warfe pulled his company back towards Well’s Junction on 14 July, but the Japanese moved faster: two days earlier, they had reoccupied Ambush Knoll, which Warfe’s men now had to capture all over again. Winterflood’s platoon moved off at first light around the precipitous eastern flank, while Meares’ platoon advanced down the main ridge-top track towards the knoll. The two Vickers guns and a 3-inch mortar provided support, with an observer in a tree calling down the range corrections.46

Meares’ men attacked along a narrow ridge-top track that sloped up to a timbered area where the Japanese were dug in behind a bamboo barricade. Keith ‘Digger’ McEvoy volunteered for the job, thinking ‘it would only be a matter of picking up the souvenirs.’ He would later write: ‘We all make mistakes at some time in life . . . that would be one of my biggest . . . when I got over that barricade with half my shirt ripped off my back by a machinegun burst and four bullet grazes across my ribs I realised it was no place for Mrs McEvoy’s little boy.’ The shouts from Ron Collins kept him going: ‘Come on, Mac, let’s go through the bastards.’ Keith Myers was also there. ‘Fire was going over the top of us more or less, and there was blokes getting hit all the time.’ Myers helped bring one out. ‘I carried him out and I put him down the track. I came back; somebody else got hit. It was bedlam, you know.’47

Garland’s section followed up the first attack, his eight men charging forward before the heavy fire forced them to ground. Then the adjutant, Lieutenant Frank Harrison, crawled up alongside Garland and said, ‘Let’s charge the bastards.’ As Pinney wrote: ‘He copped a gutful of LMG.’ He would never see his unborn daughter, Frankie Louise. Meanwhile, Winterflood’s approach across the side of the ridge through thick jungle had been a nightmare, but just before dusk his men attacked the eastern side of Ambush Knoll. After taking casualties from captured Australian grenades, Winterflood’s men pulled back.48 But the ferocity of the Australian attacks told: that night, the Japanese infantry squad and engineer platoon defending the knoll also withdrew.49

The loss of Ambush Knoll rankled with the Japanese. On the evening of 19 July, Ron Garland heard booby traps go off and firing break out further down the track. By the light of a full moon, fresh enemy troops had come up the ridge and cut the track to Wells Junction. They were now coming for Ambush Knoll. Garland told his men to open up with a broadside at waist level along the narrow approach track as soon as he opened fire. When a twig snapped and bushes moved, Garland fired and his men followed suit, cutting the Japanese attackers down.50

Back at Namling, Warfe had heard the attack and immediately sent two sections from Winterflood’s weary platoon to help. Two Vickers guns were already on their way, manned by the transport section crews. They arrived none too soon. As the second attack came in, it encountered an unexpected wall of fire.51 At dawn, Winterflood’s weakened platoon, carrying much-needed Vickers ammunition, also arrived. The Japanese launched at least fourteen attacks on 20 July, and ammunition was running low: all automatic weapons, including the Vickers guns, were switched to single-round fire.

Down at Namling, Warfe pulled Brian Walpole aside. ‘Wally, the poor bastards haven’t got any food and they’re running out of ammunition and so forth . . . see if you can find a way we can get up there without the Japs knowing.’ Since the main approach was blocked, Walpole ‘looked at this other side . . . and it’s just straight up . . . and nothing there, virgin jungle.’ Still, that would have to be it. Warfe ‘sent everyone he could up there to take stuff up,’ Walpole recalled. ‘I went up with them . . . carried some food, ammo and your own gear . . . you reckon someone would do it for you, so why wouldn’t you try and do it for someone.’52 Even Damien Parer put down his camera and helped. Jack Arden wrote, ‘It was pitch dark and raining heavily. We had to carry cases of ammo, grenades, food, tins of water and medical gear. At least we knew the direction, it was always up.’53

The enemy pressure on Bobdubi Ridge forced General Savige to divert a battalion from Moten’s brigade to take over at Ambush Knoll.54 Keith Myers was at Wells Junction when Warfe approached him. ‘I’ve got a job for you, Myers. 2/6th Battalion, they don’t know where we are, but they’re coming to reinforce us. I want you to go and find them.’ When Myers found the infantry company, one asked, ‘Are you having a bit of trouble, can’t you handle it, Snow?’ ‘You’ll find out when you get there,’ Myers said quietly.55 They did. But despite taking losses, they broke through and relieved Ambush Knoll.

After being relieved, Warfe’s company moved further north along Bobdubi Ridge and took over a position on the reverse slope of the Japanese-held Timbered Knoll. Brigadier Hammer had decided that to maintain the initiative they should attack the knoll, and in the mid-afternoon of 29 July, John Lewin’s platoon moved out to do the job. It would be a tough nut to crack, but help was available: 3-inch mortars, and a fifteen-minute barrage from the artillery on the coast at Tambu Bay. It was the first artillery support the commandos had had since they left Wau.56

Damien Parer went in with Lewin’s men. Before he left, Parer had the cook fill a drum with hot tea. ‘What are you doing?’ asked Myers. ‘Filling up with tea for youse,’ Parer replied. ‘When you take this ridge, which I know youse are going to do, we’ll have a cup of tea.’ ‘Cup of tea?’ Myers said. ‘I haven’t had a cup of tea for ages. We don’t have cups of tea here.’ ‘I’ll carry it,’ Parer said. And he did.57

While Parer filmed, ‘Bill’ Robins made his way to the top of a grassy approach ridge and was hit by a burst of fire. His lungs punctured, he rolled back down the slope and ‘Roly’ Good, the unit medical orderly, tended his wounds before he was carried out. Parer filmed it all, and later wrote: ‘I saw Robbie wounded in the back, groaning, yellowing, white in the seeming interminable wait for the stretcher to come. Roly worked deftly—Robbie let a cigarette dangle unheedingly from his mouth. As the stretcher bearers were taking him, he turned and winked at us much as to say, “I’ll be home before you anyway.”’58

The men attacking up the open ridge-side had faltered, pinned down by machinegun fire that killed Percy Hooks, Don Buckingham and Bonnie Muir. Parer wrote: ‘On the right, three men have been killed. The lanes of Jap fire are too accurate from this side. They pin us down. Swift realisation follows. A chap dashes down the slope to the side of our leader, Johnny Lewin. He decides that we’ll have to go round to the left.’59 Lewin took Lieutenant Sid Read’s section around to attack from the other side. Faced with a steep, razor-backed ridge and heavy covering fire from bunkers and trenches, Wal Dawson opened the way with Tommy gun and grenade. ‘Wally, worth his weight in gold,’ Norm Bear said of him.60 As Lewin’s men reached the crest, the defenders were facing the other way, giving them vital seconds to get onto the ridge. Fighting along the ridge line, the commandos cleared 20 metres of foxholes. Parer recorded how they ‘moved around to the Jap’s position feeling out the pits with grenades. Just rolling them in and ducking before the grenade went off.’61 The assaulting troops then linked up with the other sections, leaving eighteen enemy dead behind.

In the morning, the three fallen commandos were laid to rest as mist swirled around the captured knoll. ‘Slowly the boys filed down and around the graves took off their hats and bowed their heads as the burial service started,’ Parer wrote. ‘Hard fight, tired men—wet capes—tired eyes . . . they prayed with sincerity their homage to their three fellow comrades . . . before I left John Lewin gave me one of the Jap watches that the boys had souvenired. It was from the platoon he said. I felt awkward. Hell, what chaps these are.’62