Bobdubi Ridge

June to September 1943

Ellen Savage was drowning. Shaken awake by the impact and explosion, the Australian nursing sister had left her cabin and climbed the stairs to the deck. The ship’s bridge was ablaze, lighting up the night. Told to abandon ship, she seized a life belt and leaped into the water. Now the suction of the sinking vessel was dragging her into the depths. Caught up in loose ropes, she struggled in death’s grasp, until suddenly she shot clear like a cork, and breached the surface—alive!1

The war in New Guinea was making heavy demands on the Australian medical services. On 10 May 1943, the 195 men of the 2/12th Field Ambulance had left Sydney on the Australian Hospital Ship Centaur, destined for New Guinea. Also on board were seventy-five crewmen and sixty-two hospital staff, including Ellen Savage: 332 people in all. In accordance with international convention, the vessel had been painted white; along each side ran a wide green stripe broken by a huge red cross. Even at night, the vessel—its lights burning brightly—was clearly identifiable. The commander of the Japanese submarine I-177 certainly found it so. For him, it was a clear target. In the early morning hours of 14 May, off the Queensland coast near Caloundra, Centaur was torpedoed and sunk. Ellen Savage was one of only sixty survivors. When the wreck was discovered sixty-seven years later, the bow was found to have been almost severed from the rest of the ship.

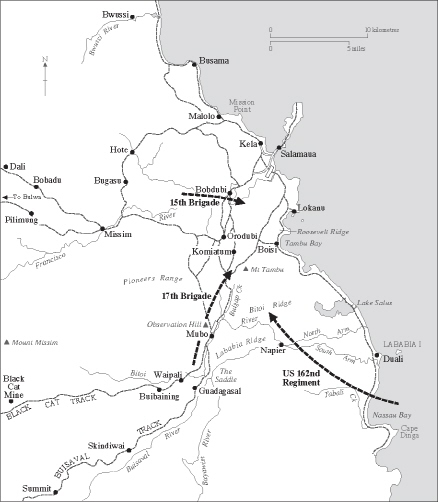

In New Guinea, the fighting continued. After the bold incursion by Warfe’s commandos onto Bobdubi Ridge, the Japanese were determined to hold onto the dominating positions at Old Vickers and the Coconuts. Meanwhile, the Australians were significantly increasing forces in the Missim area for Operation Doublet. The 15th Brigade, comprising the 24th Battalion, the 58/59th Battalion and the 57/60th Battalion, was flown to Wau. Brigadier Heathcote ‘Tack’ Hammer, who had impressed as a battalion commander at El Alamein, was the brigade commander.

The 58/59th was commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Danny Starr, who had been sacked from the 2/5th by Brigadier Moten after the battle of Wau. General Savige, who had commanded Starr in the Middle East, appointed him to the new role. After being airlifted to Wau, Starr’s new battalion assembled in the Bulolo Valley at the end of May. On 6 June, the first company began the four-day trek across Double Mountain to Missim, following the same punishing route that Warfe’s men had pioneered. Harold Hibbert remembered the crossing as ‘pretty precarious, hand over hand, had to pull yourself up along the track.’ Major Basil ‘Jika’ Travers recorded the slog in his diary: ‘We have been marching nine hours today and it was as cold as charity. I have never seen such a trail in my life. The mud and slush in the moss forest was terrific. The slush in parts was one foot deep.’2

The role of 15th Brigade in Operation Doublet would be to deliver the second of three blows designed to collapse the Japanese position in front of Salamaua. Following an amphibious landing by units of the American 41st Division on the eastern flank at Nassau Bay on the night of 29 June, 15th Brigade would attack on the west flank the following day. As the Japanese command tried to deal with these threats, 17th Brigade would strike at Mubo.3

The specific task for 15th Brigade was to move east from Missim to capture and hold the key positions along Bobdubi Ridge from where the Komiatum Track could be dominated following Warfe’s example.4 The brigade had only the 58/59th Battalion and Warfe’s company available for Operation Doublet. Its 24th Battalion was deployed to patrol the vast area south of the Markham River, while the 57/60th was guarding the site of a new airfield at Tsili Tsili, in the Watut Valley. On 29 June Lieutenant Colonel Henry Guinn, the temporary commander of 15th Brigade until Brigadier Hammer arrived, sent out a message that the enemy troops on Bobdubi Ridge were caught ‘like rats in a trap.’5

Two of Starr’s companies would make the initial attack on Bobdubi Ridge, a difficult introduction to battle for troops with no front-line experience and little dedicated jungle training, and all the more so coming hard on the heels of an arduous trek. Major Herbert Heward’s company would attack the Orodubi–Gwaibolom–Erskine Creek area to the south, while Captain Ernest ‘Ossie’ Jago’s company would move against the dominating Old Vickers position at the northern end of the ridge. Following in the wake of Jago’s company, Captain Frank Drew’s company would move across the ridge to gain control of the Bench Cut Track on the eastern side. Starr was sure that everyone knew their tasks, and said, ‘No special opposition was expected or considered.’ It should have been.6

After minimal rest, the men moved up to the start lines weighed down like packhorses. A typical rifleman carried a rifle with fifty rounds and his pack, along with 250 extra rounds, one 3-inch mortar bomb, as many grenades as possible, and a pick or shovel.7 George Warfe provided a number of guides, including Peter Pinney, who was advised: ‘Don’t get too far in front: don’t get knocked!’ Jago’s company went up to the start line at night. Rain began to fall in torrents, the steep track became slippery, and falls were frequent. Pinney wrote that there was ‘no starlight; it was overcast and pitch dark, and of course the plan was for us to all get down to the flats under cover of darkness.’8

It was around midnight when the leading units reached the kunda bridge across the Francisco River. Harold Hibbert called it ‘a rough piece of carpentry.’ Dave Taylor recalled, ‘We were all heavily laden with packs, arms and ammunition, and in addition spare mortar bombs which made balance under the conditions awkward.’ Pinney put it more pungently: ‘Thank Christ none actually fell in because they would sure as shit have drowned.’9

At first light on 30 June, the remainder of Jago’s company crossed the bridge. ‘We kept under cover,’ Pinney wrote, ‘waiting for the Vickers guns and big mortars to make their way over that gutshot bridge in daylight. No way to hide that little performance from Japs up on Bobdubi Ridge . . . it should have drawn the crabs: but nothing happened.’10

For Ossie Jago, a quiet, studious type who seldom raised his voice, this would be his first action. Two of his platoons, Lieutenant Ted Griff ’s and Lieutenant Richard Pemberton’s, would attack the crucial Old Vickers position. Pemberton, who was from Rabaul, had joined his platoon at Port Moresby; he told his men that when they reached Salamaua he would show them where the bank had buried its bullion.11 As they moved up onto the ridge, a Woodpecker machine gun opened up at close range. ‘It sounded as if it was just a few yards away, but was actually 60 yards off and well dug in,’ Pinney noted. Alarmed by the attack, the Japanese also sent over mortar rounds: ‘Incredible bloody stuff, you feel as if they explode inside your head. The only one that would have wiped out the bunch of us was a dud.’12

Pemberton halted his men behind a large clump of bamboo, looked out over the objective and asked Jack Shewan if he could see any defenders. ‘No, I can’t see them,’ Shewan replied, before handing the Bren gun to Pemberton, who could see a target. But when Pemberton fired, the Woodpecker replied, killing him.13 Pinney saw it happen: ‘I was looking around for Pemberton. He was out left, trying to get a good look at just what the Jap position amounted to—and the ’pecker put a burst into him.’14 Further left, Griff ’s platoon went unnoticed until two men accidentally fired their Owen guns. Griff then saw the ominous sight of enemy troops gesturing in his direction before a machine gun opened up, pinning his men to the ground. ‘It was impossible to move on top of the ridge,’ he later wrote.15

‘Time passed,’ Pinney noted. ‘We weren’t making any further impression on those defensive positions and the mortars were coming close; we were eight men all told and no support was coming, so with my encouragement we all pulled back. No point in being heroes when there’s no reward in sight, and one of those shocking bloody mortars is feeling for your throat.’16 The Australians were 20 metres from three enemy bunkers at the southern edge of Old Vickers. They would not get any closer for another four weeks.

Meanwhile, at the southern end of Bobdubi Ridge, Heward’s company moved forward at 0915. Lieutenant Frank Roche’s platoon was to capture Orodubi village, then the other two platoons would pass through onto Bobdubi Ridge. It was to be a surprise attack, but when a Bren gun opened fire prematurely, the twenty-odd defenders scurried for their weapon pits under the native huts. When Roche finally attacked, his two lead sections were fired on 70 metres from the Japanese position and forced to pull back. The leading Bren gunner, Brendan Crimmins, was killed and two others wounded; further back, Crimmins’s younger brother Kevin sat and wept.17 Six weeks later, he too was dead. Today they lie side by side in Lae War Cemetery.

After twenty minutes, Roche withdrew his men to Namling, leaving a rearguard behind. An annoyed brigade headquarters then issued orders to contain Orodubi with one platoon and continue moving the other two platoons past the enemy position.18 Though the officers were inexperienced, the schedules were tight and had not allowed time for proper reconnaissance before the attack, the same issues that plagued Jago. The problem with hasty attacks was that if the men didn’t succeed on their first chance, they invariably suffered heavy losses in any further attempts.

The failure to secure Old Vickers had prevented Captain Drew’s company from reaching the Bench Cut Track on 30 June and again on the following day. The men were exhausted, and the only other way forward was precipitous. On 2 July, Guinn replaced Drew with Griff and ordered a move across the ridge further south.19 The company finally reached the Komiatum Track junction, east of Bobdubi Ridge, on the following day. Their first ambush killed two enemy officers, including the 51st Division chief of staff, Colonel Tadao Hongo.20 Griff then pulled his men back to higher ground astride the track. However, when eighty Japanese soldiers moved through, the Australians made no move, and another two groups of 102 and 120 men were also left unmolested. Griff later explained that the Japanese ‘were well dispersed, moving cautiously and with weapons at the ready.’21

On 4 July, Brigadier Hammer arrived and immediately got stuck into the 58/59th. As Jika Travers observed, it did not help the situation that ‘Hammer was very full of AIF and 9 Div and Alamein at this stage.’22 He would need to adapt quickly to circumstances radically different to those he had faced in that desert battle, with different troops, less support, and diabolical terrain. He told Starr that the Japanese troops had to be fired on and that ‘the offensive spirit must be built up.’ However, as Griff had observed, the original 200 Japanese defenders had been considerably reinforced. Two fresh companies from Captain Otoichi Jinno’s I/80th Battalion had arrived by motorised landing craft from Wewak, and there were now about 500 troops defending the ridge, supported by six mountain guns. General Nakano had stressed that ‘this location is the last key point in the defence of Salamaua’.23

On 4 July, the 58/59th went after the Coconuts position at the northern end of Bobdubi Ridge. A patrol confirmed that North Coconuts was only lightly held before fire from Old Vickers forced its withdrawal. But in the late afternoon, Lieutenant Les Franklin’s platoon returned to capture the position and dig in.24 Next day, Jinno’s fresh troops counterattacked with a great deal of noise, waving of flags and blowing of bugles. After taking casualties, Franklin’s platoon was forced out again. Hammer was of the opinion that the men could have held their ground longer.25

On 7 July, Hammer specified three objectives for the 58/59th: capture Old Vickers, patrol Bobdubi Ridge between Old Vickers and Orodubi, and gain control of the Komiatum Track. So on 7 July, just a week after the first unsuccessful attacks, Jago’s men had another go at Old Vickers, ‘the thorn in the side of the 15th Brigade.’26

An air attack was laid on, but it delayed the ground attack for an hour. Two platoons advanced up the steep, knife-edged approach while mortar rounds were dropped ahead of them. The men only got to within 60 metres of the enemy’s seemingly impregnable machinegun bunkers, which were dug in and covered by a metre of logs and earth.27 Machine guns were only the start of the problem: the Japanese had brought up a 70-mm mountain gun, which killed three men with its first shell and then fatally wounded another two. Dave Taylor, who was standing with Ted Butler behind some bamboo as the gun fired, heard a swishing sound in the air, then clearly saw what he thought was a mortar bomb ‘touch the top of a cane and explode not more than ten feet from our heads.’ The attack may have failed, but it had shaken the Japanese defenders, who claimed they had been charged by 600 men. When Lieutenant Roy Klein’s platoon had another go on 9 July, Klein and two of his men were wounded, Bert Sutton mortally. Well-directed artillery fire was desperately needed.28

The Japanese were also hitting back at the southern end of Bobdubi Ridge. On 10 July Lieutenant Griff ’s supply line was ambushed on the Bench Cut Track near Gwaibolom. When a sixteen-man patrol was sent to recover the abandoned rations, it too was ambushed. As the patrol rounded a horseshoe bend where the track cut into the steep slope of the ridge, the two forward scouts were hit, Bill Ryan in the chest and Bob Caspar in the shoulder. The patrol was then fired on from behind, and Bill Ware and Bob Cotter were both shot in the legs.29 ‘Sandy’ Matheson and Ron Williams stayed with them on the track while others dragged Caspar to the rear. Matheson and Williams strapped Cotter’s legs together and, when night fell, started dragging him up the precipitous slope. Despite their devotion, he died early the next morning. At least he died with his mates, Matheson thought. Bill Ryan also died but Bill Ware did make it back, his hands and knees badly cut up: he had crawled all the way.30 Four of the other men took more than a week to find their way back to the battalion.

On 12 July, ‘Wal’ Johnson was wounded on a patrol up to the Coconuts. He was blown off the ridge, badly hit in the arm and with grenade wounds to his face. Gordon Ayre took him back to the dressing station at the edge of Uliap Creek, where he collapsed.31 Damien Parer, who had been in the area since 2 July, watched and filmed as ‘a blinded digger led by an RAP sergeant stumbles over a stony creek, then squelches ankle deep through the clinging mud of the jungle track.’32 Johnson was back in action ten days later but was again wounded, this time losing an eye. His war was over, but the image of ‘the blinded digger’ would endure. On that same day, Gordon McDonald was found near Old Vickers after surviving three days out in no man’s land with a badly wounded leg. Like the 58/59th Battalion itself, he had been given up for dead on Bobdubi Ridge.33

Time and again, the Japanese outmanoeuvred the Australians. An incident on 13 July was typical. That morning Colonel Starr, Captain Heward, and Heward’s orderly, Len Osborne, set off to find Lieutenant Griff. When they arrived at a forward post, Heward asked for Griff; the section corporal said he would be back soon. Assuming that Griff was further down the track, the three men kept on, unaware that they had passed the forwardmost Australian position. Osborne led the party around a shoulder in the track, saw a wire stretched across it, and stopped. Starr ‘looked across to the other shoulder of the re-entrant, about ten yards away, and saw two troops jump down.’ Assuming they were Australians, he called out, but the answer was a burst of gunfire. Starr turned and dived back around the shoulder, but Heward and Osborne were killed. Starr passed Harold Hibbert on the way out. ‘We got jumped,’ Starr told him.34 Japanese records told the rest of the story: ‘Destroyed an officer’s patrol (major), captured materials, code book, map, operations order etc.’35 Heward’s loss had seriously compromised Australian operations. ‘What a terrible mistake to make,’ Parer wrote. ‘It is typical of this show—there is no detailed planning—no precise coordinates in this unit.’36

The performance of the 58/59th drew considerable criticism. According to Starr, this came mainly from 15th Brigade headquarters staff and was condoned by Hammer. Starr later observed that ‘the loudly expressed opinion of the brigade command was gleefully taken up by members of the brigade staff, and the battalion signallers frequently had to listen to contemptuous remarks bandied back and forth on the one and only line.’ Ted Griff added: ‘The whole area was on a party line and all conversations were heard by signallers wearing headsets.’ Starr also thought that Hammer’s ‘methods of winning the war and mine were diametrically opposed.’ Starr favoured preserving his force for the main task of blocking the Komiatum Track, but he believed Hammer wanted to kill his men ‘pour encourager les autres.’ Hammer thought Starr incompetent and wanted him replaced, but Savige, the consummate manager, would have Starr relieved on medical grounds in mid-August. Lieutenant Laurie ‘Butch’ Proby, who was twice awarded the Military Cross, later wrote that Starr ‘was used as a scapegoat—to satisfy an ego.’37

George Warfe, who would replace Starr, considered that the 58/59th ‘officers were bewildered, particularly by the early casualties and conditions of living. This was reflected in the troops’ utter lack of confidence in their leaders and their supply organisation.’ Lieutenant Russell Mathews, who didn’t reach the battalion until August, sagely observed that ‘the AIF battalions had the grain separated from the straw in the Middle East, but the 58/59 Battalion was not able to get rid of its incapable officers until the Salamaua campaign had sorted them out.’38

Ted Griff later concluded that ‘lack of experience, in command, on active service, was our weakness.’ Proby also thought the battalion was hard done by: ‘All 1939–45 Australian troops had to learn the arts of war, and such learning takes some time no matter how well trained units appear to be.’ Proby also wondered ‘why is it so hard for commanders to truly appreciate the difficulties of fighting in such terrain?’ In his view, Hammer ‘had lots of drive—however at this stage he did NOT realise the difficulties of forward troops in the jungle.’39

Lack of experience or no, Griff felt that the battalion was judged unfairly: ‘I think 58/59 Battalion had no hope of getting its head above water during this period. It got no credit for jobs similar to those which other commanders were writing up as successes.’ Other units involved in the campaign certainly suffered similar setbacks in their first encounters with the enemy, among them Warfe’s company and the 2/6th Battalion at Wau. More recently, the 2/7th Battalion had taken heavy casualties persisting with futile attacks near Mubo.40

The officers of the 58/59th took their share of the blame for the initial failures. As Sandy Matheson observed, ‘We changed officers as often as most people change socks.’ 41 But it was not quite as simple as that: if new officers had been brought up from Australia, they would also have had to be tested in battle. The best option was to use those few who had already performed well under fire. One such man was Lieutenant Les Franklin. Recognised for his drive and ability, he was given command of Jago’s company and inherited the unenviable task of capturing Old Vickers.

The inability to capture Old Vickers was at the heart of the 58/59th’s problems, but the battalion was still imposing serious stress on the enemy there. On 23 July, Sergeant Kobayashi wrote that ‘the situation grows worse from day to day . . . this is the 71st day at Bobdubi and there is no relief yet. We must trust our lives to God. Everyday there are bombings and we feel so lonely. We do not know when the day will come for us to join our dead comrades. Can the people at home imagine our sufferings? Eight months without a letter. There is no time even to dream of home.’42

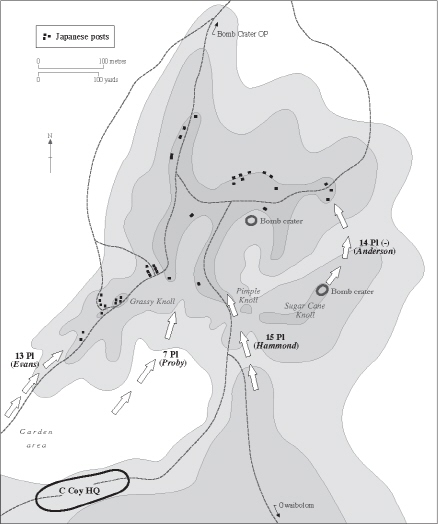

With Franklin’s company now down to only one officer and sixty-one men, the twenty-three men from Butch Proby’s platoon would also take part in the upcoming attack.43 However, the most telling addition to the attack plan would be artillery support from the 2/6th Field Regiment’s 25-pounder guns, which had been landed on the coast at Tambu Bay. The regiment faced a difficult fire task, as its rounds would have to cross Mount Tambu to reach the target. At times, the shells brushed the tops of the 4-metre-high cane stands on nearby Sugar Cane Knoll, but the gunners managed to hit their mark.44 On 27 July Lieutenant Roy Dawson brought down very accurate fire, plastering the Japanese positions on Old Vickers. For the defenders the accurate shelling must have come as a great shock. It sent them deep into their underground shelters and behind the far side of Old Vickers for protection.

On 28 July, 200 25-pound shells were fired on Old Vickers within 15 minutes, closing with a creeping barrage and mortar smoke rounds to give the infantry the best chance of success. Three platoons attacked, with Butch Proby’s men advancing across the exposed ground in the centre, and Lieutenant Jack Evans moving up on the left. Both these routes were narrow approaches, so only one or two men could deploy at the head of each platoon. The third platoon, Sergeant Vic Hammond’s, attacked up the steep slope on the right flank. Franklin later noted that ‘success appeared to hinge on getting on to the objective quickly with the bulk of my force.’45

As the bombardment finished, the Australians were cresting the slope up to Old Vickers. When the Japanese machine guns opened up, the Australians were already among them, and the sound of exploding grenades crashed out. ‘I don’t blame Nippon for keeping his head down,’ Proby later wrote.46 In Hammond’s platoon, Dave Taylor led his section in across the intervening gully. ‘As soon as the bombardment finished we went straight down . . . it was straight down and up.’ Hearing a rustle nearby, Taylor turned to see Damien Parer beside him. Taylor held his fire, but didn’t hold back on telling Parer to stay put. Cresting the ridge, Taylor’s section found no defenders there: the artillery barrage had done the trick. ‘The first bloke I shot was playing doggo,’ Taylor later said. ‘My mate had jumped over the trench and I saw him move and I fired from the hip. I can still see it . . . a little brown spot like a cigarette burn on his shirt.’47

On the left, Evans’ platoon had run into trouble as soon as they crested the ridge. Bill Lawry’s section led in, followed by Bert Ashton’s, which was hardest hit, with three of the five men in the section killed, including Ashton. Then Jack Evans too was killed as he went back to get more magazines for the lead section’s Bren. Butch Proby’s platoon had been allocated the direct approach, across the gully at its steepest point and then up a steep and narrow spur with room for only one man at a time. Proby later wrote: ‘What a high climb we have . . . on the way up the ridge, it is obvious that our request for lots of smoke has borne results . . . by pressing on we were able to reach the crest quickly . . . the smoke was so thick we had the chance to organise near the top of our spur and extend for our final charge . . . we surprised Nips coming up from underground positions tossing grenades to which we retaliated with the same medicine—ours was the best obviously.’48 The blast from one grenade caught Proby, wounding him in the hand, arm and head. As Jack Shewan passed him, Proby said, ‘Keep going, Jack—get the bastards.’49

The Australians chased the rest of the defenders off Old Vickers. The Japanese left behind four bunkers, fifty-seven covered weapon pits, the 70-mm mountain gun and seventeen dead.50 Even Hammer was impressed with the 58/59th’s performance, and he applauded the ‘determination and vigour’ of the men in following the artillery barrage.51 But he also worried ‘that the weary 58/59 may not stand up to a series of determined counterattacks,’ so he had a company from the 2/7th Battalion take over on Old Vickers.52 Japanese counterattacks cut off the position, but the 2/7th held on until contact was restored, appropriately by two platoons from the 58/59th.

The war artist Ivor Hele had been with Parer watching the 28 July attack on Old Vickers. Parer recorded that: ‘Today the boys went in and from this position we could see a wonderful battle panorama of smoke & men advancing. We were both as excited as hell.’53 Hele would later paint a stunning canvas of the battle. It now hangs in the Australian War Memorial, an enduring testament to the valour of a much-derided militia battalion at war.

By late August, the Australians had crossed the Francisco River, and Lieutenant John Bethune’s company from the 58/59th had moved up to Arnold’s Crest to take over that position’s defence. A strong Japanese counterattack on 27 August isolated Bethune’s thirty-four remaining men, who held on against increasingly fierce attacks through that day and into the next. At the end Bethune concentrated his men in a tight perimeter before another violent thrust from the east finally broke into the Australian perimeter. With ammunition low and six men wounded, Bethune withdrew, heading northeast, away from the main lines of attack, and then cutting west to rejoin the battalion.54

Seemingly blind to the realities of the situation, Brigadier Hammer signalled his new divisional commander, Major General Edward Milford, that ‘unreliability of 58/59 Bn [troops] has forced me to withdraw to hold a tighter line.’ Almost surrounded by a company of enemy troops, down to fewer than thirty men, with wounded to carry and nearly out of ammunition, Bethune’s company had, on the contrary, shown extraordinary reliability. One of the other 58/59th company commanders, Captain Charles Newman, pointed out that Hammer ‘had weak companies flung out into the blue where they could not be reinforced or supplied.’ After some reflection, Hammer approved a Military Cross recommendation for Bethune.55

By the time the 58/59th Battalion reached the coast at Salamaua, it had been in continuous contact with the enemy for seventy-seven days, having nearly one man killed for every one of those days. General Savige later paid them a fine compliment: ‘The way the 18 and 19 year olds of 58/59 Bn from 30 June–13 September kept at Japs was one of [the] outstanding feats of both wars.’56