Mount Tambu

June to August 1943

Ray Mathers was fighting for his life. The barrel of his Bren gun sizzled against the muddy earth in front of the weapon pit. He had folded up the legs of the bipod to lower the gun’s profile and used the highest gas setting to overcome stoppages. Now the barrel had welded itself to the body of the gun and was glowing red halfway back to the magazine. Not far away, at the bottom of the pit, ‘Bluey’ Kalms sat in the mud with a bandaged hand: his thumb had been shot off a short time before, along with the handgrip of the same gun Mathers was now using. Bullets cracked overhead. Then Mathers felt a tap on his shoulder. It was Kalms with a magazine that he had held between his knees and filled with his one good hand.1 The rest of the men in Mathers’ section were dead.

Jimmy Niblett also fought with a damaged weapon. He had kept firing his Owen gun until the end of the barrel had blown off, then grabbed another from his mortally wounded section leader. He kept firing until the end of that barrel blew off too. The men of Captain ‘Bill’ Dexter’s company, from the 2/6th Battalion, were desperately holding onto a muddy ridge-top position, firing down on their assailants, who were moving up both sides towards them.2 By 23 June, at the end of three days of battle, Dexter had ten men killed and twelve wounded, but his company had held onto Lababia Ridge, vital ground protecting the main track to Wau. It was the second Japanese attack on the ridge in just over a month, and when it was over, 173 of their dead would be left on the battlefield.

One week later, the Australians and Americans began their own offensive. Operation Doublet kicked off with the landing of a US battalion at Nassau Bay on the night of 29 June, but it would be some weeks before the Americans could get organised. Ultimately, however, their presence on the coast would provide a simpler supply route and allow field artillery to be landed and used to support operations as far afield as Bobdubi Ridge. With the Americans ashore and threatening the Japanese supply line, the Australians attacked Mubo and secured the high ground of Observation Hill on 12 July. Further north, near Buigap Creek, they met up with the American advance but were too late to stop the Japanese escaping back to Goodview Junction and Mount Tambu, the highest point on the approaches to Salamaua.

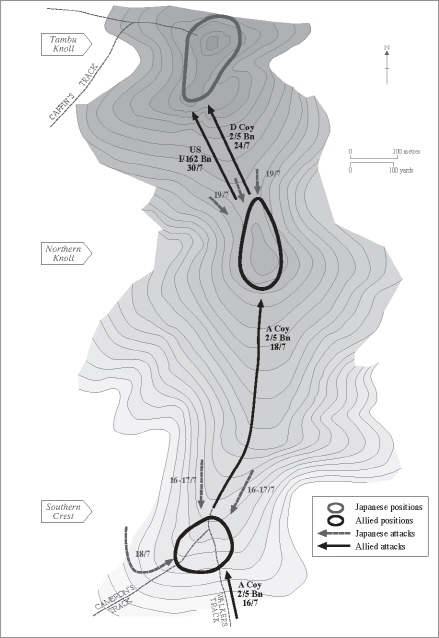

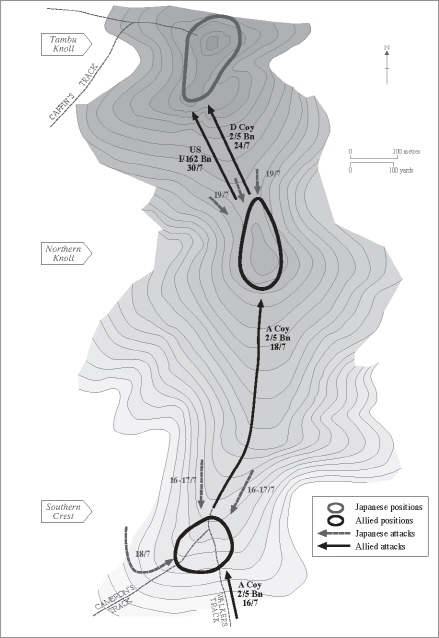

On the late afternoon of 16 July, Captain Vernon ‘Mick’ Walters led the sixty men of his 2/5th Battalion company up a steep track leading to the southern crest of Mount Tambu. Walters’ scouts reported that the Japanese had occupied two knolls just over the crest and were busy digging weapon pits. With barely sufficient room to deploy his men, Walters launched a bold attack. As Arthur ‘Unk’ Carlsen recalled, ‘Once we encountered the enemy, we attacked straight away.’ Surprise was total: ‘The forward scouts shot a Jap having a crap.’3

Leading from the front, Sergeant Bill Tiller wiped out a machinegun post as Walters’ men took the eastern of two slight knolls at the southern end of Mount Tambu. Lieutenant Eddie Reeve’s platoon captured the knoll to the west. As he had done during the battle for Wau, the cocky Reeve went in hard and fast with his men.4 It was an extraordinary coup: the Japanese defenders had built positions for over 100 men, but only about thirty were present when Walters struck. Most of them bolted after a few shots, leaving the weapon pits to the Australians, who had neither time nor tools to dig their own.5

That night the Japanese, determined to recapture the position, made eight separate counterattacks. Backed by heavy enemy mortar and mountain-gun fire, they crawled up close through the undergrowth before making screaming charges. More than 100 mortar bombs were dropped onto the Australian positions, and a searchlight from Salamaua was directed towards the position to assist the Japanese attack. By daylight the Australian riflemen were down to five rounds and the Bren gunners to two magazines each; now every round had to meet its mark. Walters noted that the ‘fighting was thick and furious during these counter-attacks and the small arms fire was the heaviest I’ve known.’6

In the forward weapon pit of Lieutenant Tim McCoy’s platoon, Unk Carlsen, the No. 2 on Jack Prigg’s Bren gun, was up to his waist in empty cartridges. His job was to reload the magazines quickly and correctly so the gun would have no stoppages. Carlsen watched as Prigg ‘used that weapon with devastating effect.’ To assist the Bren crews, Ivan Gourley moved between the positions with bandoliers of ammo. Throughout the night, the Japanese crept up close to throw grenades. As the pressure built, one of McCoy’s section leaders panicked and withdrew his men; Walters immediately ordered them back. A week later, the same section leader was killed as he sought redemption, standing up in his weapon pit to direct the fire of his men.7

With Walters’ men barely hanging on, Captain Lin Cameron managed to get the two available platoons from his company and a 3-inch mortar crew up onto Tambu the next morning via a new track from the southwest. ‘This track was much shorter and of better gradient than the old Jap track,’ he later wrote. Decorated at Wau and then given command of a company, Cameron set very high standards for his men but in return gave them his all. Captain Cam Bennett, who knew him as well as any, said: ‘Lin himself was tall, dark and intense and, during any show, completely without emotion. He led his men coldly and quietly and set an amazing example of efficient leadership. After a show he got on with the reorganisation, coldly and practically, but with tears streaming down his face.’ Ron Beaver also saw the two sides of Cameron: ‘If he lost a man it used to take him days to get over it . . . he was that sort of a bloke and yet jeez he was a good soldier.’8

On arrival, Cameron attached Lieutenant Howard Martin’s platoon to Walters’ overstretched company. Further back, another of Cameron’s platoons carried up the vital supplies that would enable the Australians to maintain their precarious hold on Tambu. At midday there were more Japanese attacks, and Ernie Pike’s newly arrived 3-inch mortar section helped to repel them. Pike, a boxer, now found himself in the fight of his life. As he later observed, ‘We have fired so many rounds at these little blighters that they must be bomb-crazy by now.’ That afternoon, as the Australians fired on Japanese troops gathering for an attack, Fred McCormack crawled out to get closer and shot eight of them. Doug Kirwan, who would be killed the following day, accounted for another four. The attack hit Reeve’s platoon at dusk, but the men, though outnumbered tenfold, held their ground. Pike’s two mortars proved crucial, ranging almost on top of the Australian lines to break up the attack but wounding at least three of Walters’ men.9

In the thirty-six hours that Mick Walters’ company held the line on Tambu, the men had repelled twenty-four separate attacks; Japanese losses were in the hundreds. At this stage, ‘The Australians were standing up in their trenches throwing grenades and firing with utter disregard for their safety, and using the most picturesque language.’ The jungle between the two forces had been obliterated by the intense fire.10 Such fighting was a ravenous consumer of ammunition, and battalion headquarters dispatched all hands to carry supplies up to the besieged company. It was a three-hour climb up the near-vertical track, and by the time the first supplies arrived, Pike’s mortars were down to three rounds. Lance Copland was in a twenty-two-man carrying party that set off along the unfamiliar track as night fell. ‘We struck a mountain stream, which marked the beginning of the nightmare ascent,’ he wrote. The men climbed up razorback ridges whose ‘precipitous sides trailed off into deep ravines.’ Their strength ebbed as they climbed, and then the rain began, adding to the challenge. The loads became almost unbearable as the men draped the bandoliers of ammunition across their shoulders to free both hands for climbing. ‘The final hill up to the forward position tested us to the limit,’ Copland continued, ‘for, at this stage, we were actually marching by sheer will-power.’ Ron Beaver said: ‘You ought to see the hill that went up Mount Tambu. You almost hit the [next] bloke in the face with your heels as you went up.’ Bill Swan, who helped lay the vital signal cable up to Walters, recalled, ‘That three miles was, I think, the worst march or climb through the most foul mountain country I’ve ever done.’11

After having held so many enemy attacks, Walters attacked the Japanese on 18 July, securing the Northern Knoll, a 300-metre-long feature where the ridge narrows before rising steeply up to Tambu Knoll. One of Bill Tiller’s section commanders, the lanky Jimmy ‘Lofty’ Jackson, single-handedly captured one position, using three grenades to clear the bunker and then his Tommy gun to silence its three occupants. The Japanese lost eighty-two killed and many more wounded; the Australians had six men killed and thirteen wounded.12

After a strenuous trek from Mubo, Cameron’s third platoon, Lieutenant Cyril Miles’ 17 Platoon, reached Tambu later that day. With the front line now further north along the top of the mount and the men clearly exhausted, Cameron told Miles, ‘Well, you’ve done all the hard work. I’ll put you in reserve. I’ll take 16 and 18 Platoon ahead where they’re likely to attack.’ With sheer mountainsides protecting his men on the flanks, Cameron told Miles that there was no need for his platoon to dig in—they should just get some rest. Taking just long enough to cut some branches to spread on the muddy ground beneath them, the men dropped where they stood.13

That night, a severe earth tremor shook the mountain. Heavy rain followed, falling in blinding sheets across the ridge. Miles’ men huddled under their rain capes, miserable and tired, but the discomfort did not stop them from posting guards to cover the track up. ‘Jim’ Regan hunched over his Bren gun, trying to protect it from the rain, while beside him his West Aussie mate Fred Allan kept the magazines as dry as he could under his rain cape. They listened to the rain being whipped in by the wind gusts swirling up from the valley and then dripping down from the trees. Then there was another sound—a strange sound, a different sound. They listened even harder, sensing something wrong and alert to any movement along the side of the ridge. ‘Cyril,’ Regan hissed back to his platoon commander, ‘there’s something out there.’ Miles couldn’t fathom it. Cameron had been sure there was no threat, and Miles had seen the terrain himself: there was no way it could be the Japanese. Then the signal line was cut, and out of the night came human cries. A chill ran up the backbone of the most resolute. Gunfire followed almost instantly, lashing the exposed Australian positions. Regan replied with the Bren, firing straight down the track: there was no other possible approach route. This fire knocked out the enemy’s light machinegun, and the Australians stymied all attempts to retrieve it.14

More than sixty years later, the look in Cyril Miles’s eyes and the quiver in his voice said more than any words. ‘You know, they just went mad, the Japs. Screaming and yelling; called out my name. It was just so unreal . . . when the Japs came charging up for their final assault, they were yelling out “Cyril, Cyril.” I can still hear it . . . I don’t know the strength of the force that hit us but it sounded like a hell of a lot . . . it was pitch black dark, I wouldn’t know how many hit us. It could have been forty, fifty, it could have been a hundred.’ Miles was one of the casualties. A bullet went through his jumper and then his arm before killing his batman, ‘Doc’ Doherty. ‘I had seven killed and six wounded in a matter of half an hour,’ Miles said, ‘I think I was around about nineteen or twenty strong in my platoon, so there weren’t too many left.’ Those who were left held their ground; had they failed, the consequences for the forward platoons would have been dire.15 The attack that almost unhinged the Australian hold on Mount Tambu had been carried out by forty men from Captain Kunizo Hatsugai’s company, part of Lieutenant Colonel Fukuzo Kimura’s newly arrived III/66th Battalion. Half of Hatsugai’s men were killed in the attempt. Japanese reports noted that the Australians were able to judge their positions and instantly pour fire down.16

Up at Northern Knoll, Walters’ men had also suffered from the elements during the wet night, but they stood to, listening to the crucial battle raging behind them. By morning they knew that the threat to their rear had been held off, but that afternoon the Japanese came again from the front. With most of the men employed in bringing up ammunition, only two Australians occupied the forward post, Percy Friend with a Bren and Jack Prigg with a Tommy gun. They held for twenty minutes until the rest of the unit returned. Then once again it was Tiller, a colossus among his men, going at the enemy with grenades and dispersing the attack.17

More attacks came, with the assailants crawling up close to the Australian weapon pits and screaming before launching their assault. Like so many of his brave men, Walters was wounded, as was his faithful lieutenant, Eddie Reeve. But despite everything, the Australians held: in this test of wills, they would not give in. Walters later wrote: ‘By 2.30 pm that day we knew we had him. Our men stood up in their trenches and sometimes out of them yelling back the Jap’s own war cry and often quaint ones of their own . . . it developed into absolute slaughter of the Japs.’18 Cameron recalled that ‘our mortar and, later, artillery broke up Japanese assaults before they got under way.’ After three days of fighting, the thick jungle on the top of the mountain was almost levelled.19 Just before dusk, Cameron’s company relieved Walters, whose men moved back to the southern edge of the mount. Meanwhile, all available troops were assigned to bring up supplies, toiling up the mountainside with their vital loads in the inky darkness.

The morning light revealed 282 enemy dead around the Australian positions on Mount Tambu. The Japanese report took its own slant on the situation: ‘We again counter-attacked, applying skilful hand-to-hand fight by small forces and holding the hill line positions firmly.’ According to a Japanese reconnaissance patrol to the south side of Tambu, there was a substantial concentration of Allied troops, seemingly preparing to attack.20 Only the second part of that assessment was accurate.

The remaining Japanese position on Mount Tambu was like a castle keep, complete with a moat-like ravine and near-vertical walls. About ten bunkers, reinforced by logs, were connected by tunnels that could shelter half a battalion, while a chain of weapon pits, some carefully positioned among the roots of large trees, was constructed on the ledge below. When the defences were later investigated, the overhead cover on the weapon pits was found to be up to four logs thick and all pits were interconnected by crawl trenches. Dugouts for sleeping and cover had been built some three metres underground, while the main headquarters had living quarters and office space built beneath about 7 metres of soil cover. The Japanese defenders would emerge like ants from well below ground, climbing up long bamboo ladders.21 The tunnel entrances were dug into the side of the peak directly behind the defence positions, allowing the defenders to shelter underground and return to their positions within seconds. The remains of the ledge dugouts and adjacent tunnels are still clearly evident more than sixty years later. Ernie Pike later remarked, ‘Our boys need to be equipped with ploughs as well as Tommy guns to get the Nips out of these funk holes.’22 One of the Japanese defenders wrote that ‘the company’s faces are pale, their beards long and bodies dirty with red soil from the ground. We are just like beggars.’23 But they fought like demons.

On the afternoon of 23 July, Brigadier Murray Moten ordered that the final position on Mount Tambu be captured the next day. Cameron immediately requested a delay for reconnaissance so as to, in his words, ‘ascertain whether such an order was practicable.’24 Cameron would attack on the left flank with two platoons forward, while Walters, with another platoon under command, would move up the newly blazed Caffin’s Track to the west of Mount Tambu and attempt to cut the main Japanese supply route back to Komiatum.

Covered by Corporal John Smith and another rifleman, Cameron crawled forward at first light on 24 July. He pinpointed seven enemy bunkers that had sharpened bamboo stakes set into the ground in front; these formed part of two defence lines. Cameron advised that a flank attack had the best chance, but was told that Moten had ordered that a frontal attack also be made. With three officers and fifty-four men up against some hundreds of defenders entrenched on a precipitous knoll, Cameron had few illusions about the likely outcome.25 His opinion counted for nought.

While the Allied artillery and mortars lashed the ridge, the Japanese soldiers waited out the barrage in their shelters. At 1130, Cameron went forward with Sergeant Alvin ‘Hungry’ Williams’ platoon on the right and Lieutenant Bernie Leonard’s platoon on the left. Cameron hoped to drive a wedge into the line of bunkers and then use Lieutenant Martin’s platoon to move through and clear the top of the knoll. Cameron’s men approached to within 20 metres of the enemy bunkers ‘before all hell let loose.’ One of the men in the forward section was killed and Cameron had his right elbow shattered by a machinegun bullet. As he saw his men hesitate, the wounded captain called out, ‘Well, I’m stuffed. Get stuck into the bastards.’ The Japanese bunkers were well covered in soil, leaves, and ferns, with just a narrow firing aperture in front. Williams found them difficult to spot until he was almost on top of them. He had plenty of hand grenades on his belt and managed to get in close enough to drop some through the bunker apertures while Vic Carey provided effective covering fire. With his men falling around him, Williams then carried out Harry Hine, who had been shot in the leg.26

On the left, Leonard’s platoon knocked out two bunkers before heavy enfilading fire forced his men to ground. With his right arm useless and his eyesight blurring, Cameron handed over command to Martin, who then put Smith in charge of a platoon. The fair-haired, solidly built Smith took the eleven remaining men through to follow up Williams’ success. As they headed for the crest through three lines of enemy bunkers, the courageous corporal called, ‘Follow me!’ Cameron’s last view before staggering out was of ‘Smith heading up Tambu with the bayonet.’ Three men managed to stay with Smith, but Japanese grenades caught them as they broke through a third line of bunkers. Smith too was hit, but he kept on. Soon he stood atop the final knoll, his back to the enemy, yelling, ‘Come on, boys! Come on, boys.’27

Without further support, and with no indication that Walters had made any progress out on the left flank, Martin had to pull his men out, giving up their hard-won wedge into the Japanese defences. Two of Cameron’s men had been killed and fourteen wounded. The big stretcher bearer Leslie ‘Bull’ Allen helped get the wounded out and dress their injuries. The gallant Smith had to be dragged out: he would die two days later. Smith had, as Cameron recalled, ‘some forty-odd [wounds], the doctor told me later.’ Smith had been decorated for similar bravery in Syria in 1941, where he had cleared out three machineguns at a roadblock. Then, despite being badly wounded at Wau, he had come back for more at Mount Tambu. One of Smith’s former comrades later remarked that ‘death held no fears for him.’ Cameron requested that some of his men be recommended for awards but was told there was ‘not much hope with our Brig [Moten] for such to go through when the attack was a failure.’ Did that diminish John Smith’s bravery? His proud father thought not, and wrote to Prime Minister John Curtin, pointing out that his son ‘sought not to save his own life.’28

Meanwhile, Max Caffin led Walters’ depleted company up the steep track from Buigap Creek while the attached platoon took up a blocking position across the main Japanese track to protect the left flank. Things began badly when five Allied artillery shells burst in the treetops overhead, killing one of Walters’ men. Caffin went forward with Bill Tiller and a scout to look at the Tambu Saddle track. They spotted two enemy soldiers, but as the rest of Walters’ company came up so did a company of 125 Japanese infantrymen, moving up from Goodview to reinforce Tambu in response to Cameron’s attack. Outnumbered, Caffin allowed them to pass before Walters’ men moved into the attack. They hit strong enemy positions along the saddle, but after Bill Tiller was killed by fire from the bypassed position, the attack was called off.29

Although the 24 July attack failed to capture Tambu Knoll, it had achieved more than could fairly be expected of such a small force. Even if Walters had got behind Mount Tambu, Cameron’s men would still have faced the nearly impossible task of storming the bunker lines. The ferocity of their assault can be gauged from the Japanese account, which claimed that 400 troops had attacked with mortar and artillery support. The records also make clear the impact of John Smith’s action: ‘One portion of the enemy, fiercely throwing hand grenades, counterattacked repeatedly and fiercely advanced into our position.’ The Japanese admitted to having twenty men killed and twenty-one wounded in the action.30

Four days after the failure of the latest attack, the Australians moved out of the front line on Mount Tambu. Back at Wau Hospital, Mick Walters told Damien Parer that a different approach was required. He espoused assailing the bunkers with flammable explosive delivered from planes fitted with belly tanks. Napalm bombs, though not available at this point, would be introduced later in the war. General Savige also met Walters at the end of July and noted that the company commander ‘was full of praise for the gallantry of his troops but it was evident he had lost confidence in his CO and was bitter about some frontal attacks the battalion was ordered to undertake.’ The attack on 24 July had been ordered by Lieutenant Colonel Tom Conroy without any first-hand knowledge of the terrain or the condition of the men he was sending into combat there. However, it was Moten who pulled the strings. He later tried to deflect the criticism, saying, ‘Conroy was trying to run the battle from too far back and I had to give him a kick in the pants.’31 When asked to comment on the battle after the war, Conroy declined.

How much can be asked of any troops? Walters’ company was only sixty men strong when it stormed Mount Tambu on 16 July. After fighting off two dozen Japanese counterattacks in thirty-six hours, they were ordered to make a further attack, in which they captured the Northern Knoll and then held it against fierce counterattacks. Lin Cameron’s depleted company also suffered, particularly Cyril Miles’ platoon. Yet it was then ordered to make a frontal attack on the toughest position on Mount Tambu. There were 743 enemy troops in the Tambu–Goodview–Komiatum area at the time, most from Colonel Katsutoshi Araki’s fresh 66th Regiment.32 With American relief imminent, it seems likely that both Moten and Conroy were trying to upstage the Americans—more of the same attitude that had cost so many Australian lives on the Papuan beachheads. Whatever the reason, Walters’ and Cameron’s companies paid a heavy price, bled white on Mount Tambu.

On 28 July, the Yanks arrived. Ron Beaver watched: ‘One morning things were nice and quiet and all of a sudden these bodies started to come up this track, and there seemed like a million of them.’ Not quite. Toiling up Mount Tambu were three companies from Colonel Archibald MacKechnie’s 162nd Regiment, part of the 41st Division, about 500 men. Craig Agnew was in the 2/5th’s intelligence section and often had to accompany American patrols. He would tell them, ‘You guys go ahead; I don’t know if I want that firepower up my arse.’33

Lieutenant Colonel Harold Taylor’s 1/162nd Battalion had landed at Nassau Bay on the night of 29 June, coming ashore amid the crashing surf in a ‘shipwreck landing.’ All but one of twenty-four landing craft was wrecked on the beach. Like the 32nd Division at Buna, the 41st Division troops struggled to adapt. Bob Burns later recalled, ‘The training we had didn’t do much for us when we came to the New Guinea jungle.’34 On the first night there were forty-five casualties from gunfire around the beachhead, yet it is questionable whether any enemy soldiers were present.35 The Americans were not terribly particular about whom they fired at: when a RAAF Boomerang flew over the beachhead on 5 July, it was promptly shot down. The pilot, Flying Officer James Collier, was killed when he crash landed on the beach.

With orders to move quickly to cut the Japanese supply line to Mubo, MacKechnie took more than a week to get his men into position, and then they were too few for the task. This had allowed the Japanese driven out of Mubo to withdraw to Goodview Junction and Mount Tambu unmolested. The Americans had also moved north along the coast to Tambu Bay, opening a crucial coastal supply link for all Allied units in the Salamaua area. The problem was that they could not take Roosevelt Ridge, the imposing northern bulwark overlooking Tambu Bay. The position proved as stubborn as the man it was named after, Major Archibald Roosevelt, a cousin of the incumbent President. His battalion had struggled to make any headway, not least because of him. General Savige and Brigadier Moten went up against Roosevelt over whether his force was or was not under Australian control, and he was soon sent south. The ridge would remain unconquered well into August.36

Captain Delmar Newman’s company took over the front line on Northern Knoll, while Cameron’s Australians continued to hold a firm base of fire on the left. The second American company, led by Captain John George, held the southern end of the mount. Here the Americans’ 81-mm mortars were deployed alongside the Australians’ 3-inch ones. Ron Beaver watched as ‘they nearly dug bloody Tambu away getting into position.’ Late on 29 July, eight 105-mm guns and five Australian 25-pounders opened fire on the Japanese positions. The barrage continued all night, and in the morning the mortars and machine guns joined in. Beaver observed: ‘They blew the shit out of the place . . . they burned barrel after barrel out of their Brownings . . . the jungle was disappearing at a hell of a rate, everything was chopped down.’37

Two thirty-man platoons from Newman’s company advanced under cover of the Brownings, heading for the right flank. The first terrace on the slope up to the knoll had eight bunkers, six of which were knocked out, along with two Juki machine guns, destroyed by rifle-fired anti-tank grenades. Then, as the infantry moved up onto this terrace, the defenders on the second, higher tier opened fire. Grenades were also rolled down the slope, and a machine gun enfiladed the terrace from the far left. Using the extensive tunnel and trench system, other enemy troops moved back into the previously neutralised bunkers on the left and opened fire. The two American platoons were trapped and unable to move.38

Newman’s reserve platoon now moved up, climbing up the slope to the left of the earlier attack, straight towards the centre of the Japanese stronghold. Fierce enfilading fire from the left flank soon halted this move; if the attack was to progress, those positions needed to be dealt with. George’s company was given the task, his first platoon moving forward at midday. To protect their left flank, one of the Brownings was moved even further left to fire into the key bunker on that flank. However, as the platoon moved down into the ravine at the base of the knoll, another Japanese bunker even further to the left was now able to bring fire to bear. At the same time, the supporting Browning had its line of fire masked. The platoon commander, Lieutenant Barney Ryan, was immediately hit, along with one of his corporals. In half an hour, four men had been killed and another twenty-five wounded; only six men remained untouched. Lieutenant James Clarke just lay down as flat as he could and wondered how he would survive.39

Now forward with his men, the gallant Captain Newman had machinegun rounds pass through his shirt sleeve and take the pockets off his webbing belt. Colonel Taylor finally ordered a withdrawal. The mortars laid down smoke rounds, and the Brownings fired off 17,000 rounds to cover the move back. Within an hour, the men of Newman’s three platoons had extricated themselves, but Ryan’s shattered platoon on the left flank took longer. Taylor was concerned that a Japanese counterattack would threaten his main position on Northern Knoll. ‘Had the Japs attacked,’ Beaver observed, ‘the Yanks would have lost the rest of their blokes because we would have killed them all . . . that was the order, and our mortar was then ready with the HE.’40

Masao Shinoda later wrote: ‘On this occasion, the camp was secured owing to the efforts of our machinegun company and a platoon from the battalion artillery unit. Our defending troops had become familiar with the method of attack of the enemy, who would advance after close artillery support. Consequently, we would ride out the artillery inside bunkers, then our ground troops would pour down withering fire on the attackers.’41

Two American medics, Byron Hurley and Samuel Sather, were killed trying to bring in some of the fifty-three wounded Americans. 42 The Australian stretcher bearer Bull Allen again stepped forward, responding to plaintive cries of ‘Bull, Bull, Bull.’ Clyde Paton watched as ‘Allen came ploughing hurriedly upwards through the slippery mud. He brushed past me and then was lost to view . . . Shortly, back came Bull Allen with a soldier draped over his shoulders. Under the weight he staggered a little and then lowered the body to the ground right before me.’ Paton watched Allen go out, again facing the prospect of being shot like the men he rescued. However, ‘Providence watched over him.’43

Twelve times Allen went forward and brought back wounded Americans. Watching him carry in the last man, Lance Copland thought that Allen was at the end of his tether. Ron Beaver observed: ‘He had about seven touches altogether [from enemy rounds] but he had holes in his hat, he had holes in his sleeve, he had holes in his pants, he had holes under his shirt . . . Jesus Christ . . . and each time he went out, the Yankee O Pip blokes [forward observers], they were having bets . . . Do you think he’ll make it this time?’ Allen survived and would be awarded the American Silver Star to wear beside the Military Medal he already held for similar work during the battle for Wau. Astonishingly, his own country did not decorate him.44

Now realising that Mount Tambu was essentially impregnable, the Americans reverted to their artillery. Shinoda wrote that ‘going into August, artillery became for us a part of everyday life.’45 In the end, success for the Allies would come from Captain Harold Laver’s company of the 2/6th Battalion. After extensive reconnaissance, Laver’s men moved across Buirali Creek from Bobdubi Ridge and forced a lodgement on Komiatum Ridge at daybreak on 16 August. This cut the enemy supply line to Mount Tambu and, though the Japanese counterattacked with vigour, the Australians held the position. Concerned by the stalemate on Tambu, General Blamey’s deputy, Major General Frank Berryman, had arrived at the front to distribute bowler hats (dismiss commanders). He ended up noting that Laver’s attack was ‘the best bit of tactical surprise I’ve seen in the campaign and will crumble the Nip front.’46

That it did. On the night of 18–19 August, the Japanese abandoned their forward positions at Mount Tambu and Goodview Junction. But the defenders had not yet exhausted all their options. There were other hellish features in the Salamaua hinterland: Charlie Hill, Kunai Spur, Arnold’s Crest and Rough Hill among them. All had to be wrested from a tenacious enemy before Salamaua could be captured. Ironically, the Australians had never wanted to capture Salamaua. Their objective was only to keep as many enemy troops as possible defending it and therefore away from Lae. Salamaua was a feint for the main move to seize Lae. Salamaua would fall, but not until a week after the Australians had landed at Lae.

Each year in August, some of the few remaining veterans of the 2/5th Battalion gather to commemorate Tambu Day, proudly saluting their mates’ endurance and bravery on the tambu—‘forbidden’—mountain. Local legend tells of a wild boar that devours those who go to the mountain. In 1943, the mythical beast had its fill.