Captain Gordon King’s maxim was fire and movement. He had drilled it into his men over the preceding months of intense training on the Atherton Tablelands, inland from Cairns. Having served as Major Harry Harcourt’s 2IC during the Papuan campaign, the twenty-four-year-old now led the 2/6th Independent Company. He drove his troops hard—to them he was the ‘boy bastard’. ‘Fight on your feet and on the move,’ was King’s rule. ‘Never be static, never be on the ground.’ Down low, he argued, a soldier’s vision and aim were severely restricted. In place of shovels, King’s men carried extra ammunition, and with eighteen Bren and ninety Owen guns spread across nine sections, they had great need for it. The 2/6th had been attached to Major General George Vasey’s 7th Division in a reconnaissance role, ready to strike swiftly. Now Vasey was about to let it loose.1

After Lae fell on 16 September, Major General Ennis Whitehead, the deputy Allied air commander, told Herring and Vasey that he wanted Kaiapit—a village about 65 kilometres up the Markham Valley west of Nadzab—taken. Its small grass airstrip would be a good site for a fighter base to facilitate the air offensive against Wewak and beyond.2 The need to secure Kaiapit gave Vasey the perfect opportunity to use King’s company. After waiting in the marshalling area three mornings in a row for no result, the commandos finally got the order to go on the morning of 17 September. They toiled in the pre-dawn darkness to load the thirteen Dakota transports, and soon after dawn, the lumbering ‘goony birds’ rose from their earthen nests.3

In a country where soldiers had had to throw the textbooks of warfare out the window in order to adapt to the extraordinary terrain, the Markham and Ramu Valleys presented the most extensive stretch of level and open ground in New Guinea. Flanked by imposing mountain ranges, the valleys formed a broad corridor leading west from Nadzab, a natural route of advance that also provided excellent sites for airfields.

The planes carrying King’s company were to land on the western side of the Leron River, 46 kilometres up the valley from Nadzab, in a stretch of open grassland selected by the US engineer, Lieutenant Everette ‘Tex’ Frazier, that had been burned off by incendiary devices. Moving overland from Chivasing, two platoons from Captain John Chalk’s Papuan Infantry Battalion company also reached the west bank of the Leron that day, headed for Sangan. They served as a screen ahead of King’s men.4 Fred Ashford, who was in the fourth plane down, recalls that it bounced three times on landing, a testament to the sturdiness of the Dakota’s landing gear. He and the other men were seated along the sides of the plane, facing each other across the gear piled up—rather chaotically, Ashford thought—in the centre. Twelve planes were soon down, but the thirteenth and last continued to circle: only one of its wheels had locked down. The pilot managed to bounce the plane off the single wheel, keeping the opposite-side wing in the air as long as possible before bellying in for a safe landing.5 The undercarriage collapsed, however, making take-off impossible.6 But the audacious choice of the Leron landing area had succeeded: the Allies had inserted a fully equipped commando company behind enemy lines. The company spent the day organising the supplies and preparing for the move to Sangan.7

With Vasey’s instructions for urgent action ringing in their ears, fifteen officers and 176 men headed off to Sangan early the next day, 18 September. King waited until after midday for Vasey’s Piper Cub to fly in; Vasey confirmed the instructions to capture Kaiapit while holding a firm base at Sangan. Warrant Officer Peter Ryan, from the Australian New Guinea Administration, also arrived at the Leron River that day to organise the thirty native carriers who would carry the remaining supplies to Sangan and beyond. That morning, King had ordered Lieutenant ‘Ted’ Maxwell’s section to continue from Sangan that same day and reconnoitre the approaches to Kaiapit. That done, Maxwell was to rendezvous with the main body of the company the next day at Ragitumkiap, 2 kilometres south of Kaiapit. The timing of the company’s move to Kaiapit on 19 September was crucial. The men would cover as much of the distance as possible in the cool of the early morning, taking a ten-minute break every hour. King needed to reach Kaiapit in the afternoon: it must be cleared and a defensive perimeter formed before nightfall.8

Despite the level ground, the head-high kunai grass through which the track passed held the heat and humidity like a blanket, sapping the energy of men heavily weighed down with ammunition. Just as worrying, King had left the unwieldy main wireless radio at Sangan and was equipped with only four of the Army’s new portable No. 208 radio sets. Only a kilometre out from Sangan, he lost wireless contact. His company was on its own, isolated out in front of 7th Division.9

But King pressed on, and by mid-afternoon the company had arrived at Ragitumkiap, only 1500 metres from the start line for the attack. Excellent maps and aerial photos had enabled King and his officers to put the plan together in Moresby. There were an estimated sixty Japanese in Kaiapit, but none of them appeared to be occupying Mission Hill, the dominant feature in the area. Instead, the defenders were thought to be located in Kaiapit’s three villages and just to the south, where the track entered the village area. As King approached from that direction, he could see Maxwell’s section out to the northeast, moving back from Kaiapit through the foothills, trying to evade an enemy patrol that King could also see. When a series of shots rang out across the foothills, it was clear to an annoyed King that Maxwell had been compromised.10

Alex Mackay was a Bren gunner in Maxwell’s section. He could not only hear the shots being fired, he could see them whistling through the grass. Ahead of him, the rest of the section had scampered into a dry gully as the enemy patrolmen moved towards the ridge top like hounds on the scent of a fox. Under strict instructions not to engage, Maxwell had pulled the section back. But as Mackay turned and raced off down the hill, the double sling on his Bren gun caught up in his legs. He only just managed to find cover in some scrubby kunai as the enemy patrol crested the ridge above him. Content to have seen off the Australians, the patrol remained there.11

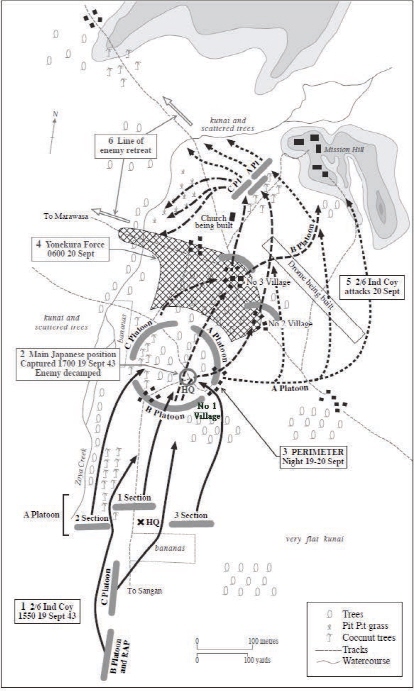

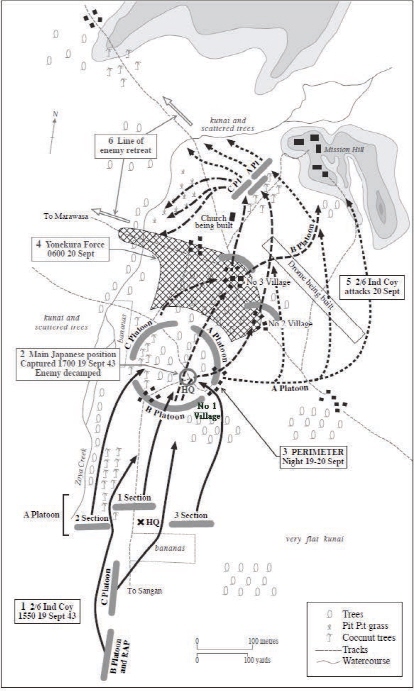

By 1515, the main body of the company had formed up in the kunai on the edge of swampy ground about 1200 metres south of Kaiapit No. 1 village. Ahead lay more kunai, masking the village and its Japanese defenders. Captain Gordon Blainey deployed the men from A Platoon on a wide front, with Lieutenant Sam Southwood’s 1 Section straddling the track that would be the axis of advance. Lieutenant Bert Westendorf ’s 3 Section was to the right of the track and Lieutenant Reg Hallion had his 2 Section to the left, his flank up against the dried up watercourse of Zoya Creek. To help compensate for the shallowness of Blainey’s line, King positioned Captain Derrick Watson’s C Platoon behind it, with Lieutenant Geoff Fielding’s B Platoon at the rear. Fielding was still without Maxwell’s section but had a PIB section attached. King’s headquarters was behind Blainey, just off the axis of the raised track.12

King had given strict instructions that there was to be no movement on the track itself. ‘For chrissakes,’ he told the men in the lead section, ‘don’t walk on that bloody track.’ Around 200 metres from Kaiapit No. 1, however, an exhausted Tom Gimblett stepped out of the suffocating kunai and onto the track. ‘I can’t walk any further through this,’ he told his mate Wally Hagan. At this point, the track was slightly elevated, providing a straight approach to the village through the kunai. But as King had foreseen, the enemy had covered this approach with a machine gun. Its fire killed Gimblett and wounded King in the leg. The rest of Blainey’s men kept steadily on through the kunai grass.13

Fred McKittrick and Hagan set up the 2-inch mortar to try to counter the enemy fire. ‘Where do you reckon it’s coming from?’ McKittrick asked. ‘Looks like the pandanus clump,’ offered Hagan—that was the only visible cover lined up with the track. Hagan set the mortar for full range, about 220 metres, then laid out four bombs and dropped a fifth down the tube. Flicking the wheel at the mortar base to engage the firing pin, he fired all five bombs. All hit their mark, smashing the enemy position. ‘Let’s go and get them!’ shouted Blainey. Southwood’s section stormed into the village, rapidly clearing the forward weapon pits, the occupants either fleeing or dying at their posts. The tactics were reasonably simple. The Australians kept the defenders pinned down with grenades, then rushed them, putting King’s maxim of fire and movement into deadly practice.14

Meanwhile, Westendorf ’s section had swung out to the right flank, led in by two scouts. Charlie Banks was on the left with the Bren gun, keeping Southwood’s section in sight to ensure there was no gap and that the sections did not overlap in each other’s line of fire. A shot rang out and Westendorf went down, hit in the head by a sniper hidden among the trees up ahead. The men responded quickly. Raking the trees with gunfire, they went in hard, sweeping around the village huts and clearing the weapon pits at close quarters. As Banks entered the village, another commando warned him, ‘There’s Nips in that hut, keep your eye on them.’ The hut was elevated on log stilts, and Banks saw an enemy soldier’s legs appear below floor level on the other side. That was enough: a burst from the Bren cut him down.15 Meanwhile, King hobbled forward through some shrubbery and out onto the cleared ground between the coconut trees. There he saw ‘Blue’ Burrows, one of Westendorf ’s men, still dealing with some weapon pits. ‘Look out, Sir, get out of my bloody way,’ Burrows shouted, firing his Owen gun and then rolling grenades into the pits.16

The Japanese defenders had been in a strong position, but the force and fury of the assault had decided the issue. Thirty of them lay dead and the rest had fled. Three of King’s men had been killed and seven others wounded, including Syd Graham, who kept on fighting: one-third of the enemy’s death toll was his doing. ‘Snowy’ Boxall, a Kalgoorlie lad, had been badly wounded and was sewn up by the first-aid man. Early next morning, a grenade landed near him; as he crawled away, the wound opened up and he bled to death.17

At 1630, King called Watson’s platoon forward and the men moved through the Kaiapit villages, across the landing ground, and up onto Mission Hill, clearing the whole area before night fell. That job done, the platoon returned to the perimeter that had been formed around the huts of Kaiapit No. 1. Three villagers had been found tied to poles in one of the huts and bayoneted. About 1700, Lieutenant Doug Stuart, an Australian officer with the Papuan Infantry Battalion, showing initiative and stamina, came up from Sangan to take back the message that Kaiapit had fallen. He dashed back to Sangan to report to Captain John Chalk that the 2/6th was in a tight spot and ask the PIB to establish a firm base half an hour to its rear. Two PIB platoons were sent forward the next morning.18

At Kaiapit No. 1, the Australian defensive perimeter had booby traps laid out in front. Watson’s platoon was in the northwest sector, Blainey’s to the northeast, and Fielding’s at the southern end. Like most of the men, Tom Strika had only his bayonet to dig in with. It made little impact on the hard-baked earth, so his shelter for the night was a mere scrape in the ground.19 At about 1930, a native approached the northeastern quarter of the perimeter and called out in pidgin that he had a message for the commander. Only when he reached King’s headquarters did the man realise that Kaiapit was now occupied by the Australians. He cried out, turned and ran, only to be felled by an Owen gun. When a note in Japanese was found on the courier’s body, King knew that more enemy troops must be close by. When later translated, the note was found to read: ‘We believe there are friendly troops in Kaiapit. If so, how many and what units?’20

At 2000, a six-man Japanese patrol, probably the one that had earlier chased Maxwell, marched toward the northeastern segment of the perimeter. The soldiers, rifles slung over their shoulders, were singing and chanting, clearly unaware about what had happened at Kaiapit that afternoon. At the last moment, the silence alerted them. As they unslung their rifles and crouched down on the path, a Bren gun opened up at point-blank range, killing them all. Another four enemy soldiers returned to Kaiapit at about midnight. This time, one of them got away, his cries echoing off the foothills as he ran.21

For the men on the perimeter, it was a tense night. Every shadow was potentially an enemy soldier. Adding to the sense of foreboding were the howls of wild native dogs, attracted by the scent of blood, and the ubiquitous swarms of mosquitoes, also in search of their share. Brief heavy showers compounded the men’s discomfort; when they stopped, fireflies danced across the sky. Watson’s platoon prepared to move out when first light came. The plan was for Lieutenant Bob Scott’s 7 Section to advance on the left, beside the creek, and Lieutenant Bob Balderstone’s 9 Section to go on the right. Watson himself was to accompany Lieutenant ‘Jack’ Elsworthy’s 8 Section, which would move along behind. Watson wasn’t expecting any resistance.

What Watson did not know was that a much larger enemy force was moving down the track from the northwest, heading directly towards his line of advance. As many as 500 Japanese troops were on the march, eager to reach Kaiapit before dawn’s light exposed them to prowling Allied aircraft. Having sent out a messenger, Major Tsuneo Yonekura assumed that the Kaiapit garrison would be awaiting his arrival. His force, designated the Yonekura Tai, was substantial, comprising three infantry companies, an engineering company, a heavy machinegun section and a signals section. Wary of Allied aircraft, the unit had travelled by night since leaving Kankiryo, further up the Ramu Valley, on 12 September. Yonekura intended to use Kaiapit as a base from which to strike the Australians at Nadzab, thus enabling the remnants of the 51st Division to withdraw across the mountains to join him.22 But the major was way behind the game. Vasey and King’s decision to strike swiftly had paid huge dividends: if King had been delayed by a single day or if Yonekura had arrived a day earlier, King’s commandos would have faced a much stiffer defence and taken much heavier casualties.

Just before dawn on 20 September, as Watson’s men made their final preparations to move out, they spotted the head of the Japanese column and immediately opened fire. This brought chaos to the Japanese ranks as the rest of the column bunched up and milled about, utterly confused in the early-morning half-light. Some screamed out that they were Japanese and to let them through, but others realised that Kaiapit had been captured and opened fire. The shots soon became a torrent. Thousands of rounds were fired, but all passed harmlessly over the Australians’ heads. King watched as the confused enemy infantrymen did exactly what he had taught his own men not to, shooting at shadows, wasting ammunition and firing too high. ‘In all that enormous activity of firing,’ King observed, ‘nobody got hit, nobody got hurt at all.’23

For King too, the situation came as a shock. The volume of fire indicated that a considerable force was gathering, and it would be right in the line of Watson’s intended advance. Watson wanted to move immediately, but King held him back, wanting to trap more of the approaching force and also shore up Watson’s left flank with Geoff Fielding’s platoon in case more Japanese approached from that direction. Watson watched for King’s signal, each second seeming like a minute as the Japanese gathered in the half-light. ‘He was standing up there, looking back to me, waiting,’ King later remembered. When King dropped his arm, Watson blew his whistle and his men advanced. They ‘killed over a hundred Japanese in the first 100 yards.’24

With their automatic weapons blazing, the Australians waded into the mass of enemy soldiers. But the Japanese did not go down easily. On the left, Scott’s section came up against very heavy fire. John Tozer was shot in the chest at close range, but the bullet hit his identity disc. ‘It was like being belted in the middle of my chest with a sledge hammer,’ he later wrote. ‘The bullet cartwheeled across my chest tearing a good shirt to shreds and leaving a nasty—but quite superficial—burn.’ Tozer was not the only man to have a lucky escape. Derrick Watson had two: he was hit on the hip by grenade shrapnel that deflected off his wallet, and soon afterwards a bullet tore away a swivel on his rifle. He emerged unscathed. Yonekura and his command group were not so lucky, cut down by the first wave of Australian fire.25

Lieutenant Bob Balderstone took 9 Section in on the right. At twenty-two, Balderstone had been through the Army NCO school and Officer Training Unit before being attached to a Victorian pioneer company alongside Bert Westendorf and Reg Hallion. The three officers had then been allocated to the 2/6th as section commanders, joining the company on the Atherton Tablelands in March 1943. Only Balderstone would survive Kaiapit. He now led his section forward over relatively open ground, with only scattered coconut palms providing any semblance of cover for the Japanese. Balderstone knew the attack had to be fast and furious to maximise the advantage of surprise and minimise ammunition usage.26

One of Balderstone’s men, Lori Vawdon, who was in his first action, found it very hard to see anything in the early half-light. He soon came across Cliff Russell, a Bren gunner from Scott’s section, who had been shot in the wrist. ‘Here, take this,’ Russell said, and thrust the Bren into Vawdon’s arms. The gunner had already done considerable damage, killing twelve enemy soldiers, including an officer and a native mercenary, before he was hit. Nearby, Vawdon saw a good mate, Wally Blake, dead on the ground, another loss from Scott’s decimated section.27

On Watson’s command, Jack Elsworthy’s section moved forward in a line behind the leading sections. Jim Clews and his mate Johnny Haine, who had transferred to the commandos from a docks company at Port Moresby, advanced side by side, heading straight for a machinegun position. They fired on the move, looking for clear targets. Clews carried a rifle with spare ammunition in the bandolier around his neck and extra grenades in his webbing pouches. The Japanese machine gun was hidden in some bushy scrub, and Elsworthy’s men were unsure if the forward sections had knocked it out. About 20 metres on, amid the roar of gunfire, explosions and shouting, Clews heard another sound—a warning shout from Haine. Looking to the right, towards the machinegun position, Clews saw a wounded Japanese soldier with a rifle. Moments later, a bullet lanced through Clews’ lower leg and he collapsed to the ground, his fight over.28

Though the Australians had seized the moment, their victory was not without cost. Watson’s platoon lost eight men killed and another fourteen wounded, most from Scott’s section on the left. The initial advance took Watson’s men to the northern edge of Kaiapit No. 3 village; to their front, an enemy machine gun covered the clearing beyond the huts. Almost out of ammunition, Watson had his men hold position while he moved back to get a resupply. He suggested to King that if Blainey’s platoon could be brought around on the right flank, the rest of the Japanese could be cleaned up. However, the first priority was for Blainey to get a section up onto the high ground of Mission Hill, which dominated the battlefield.29

Meanwhile, Lieutenant ‘Dickie’ Row’s medical section had moved through in the wake of Watson’s attack and, with the help of all the headquarters men, brought in the wounded. Any who could not walk were brought back to the aid post on groundsheets. As Jim Clews was helped back, his rifle and spare ammunition were taken forward to help Watson. Half an hour after the first contact, King committed Blainey’s platoon out on the right flank, keeping Fielding’s platoon back to hold a firm base and cover the evacuation of the wounded. Blainey had already briefed all his section leaders to be ready to move; they were to head for Mission Hill.30

As they had on the previous day, Blainey’s sections advanced in an open line, looking out for any Japanese fleeing in the wake of the thumping Watson’s men had given them. Charlie Banks was at the head of a spearhead formation with the Bren gun slung from his shoulder, held in place by two joined rifle slings. He had a man on each side, about 2 metres away and somewhat to the rear, leaving him a 180-degree arc of fire to the front. Wedging the butt of the gun into his stomach, Banks used the top handle to swing the muzzle from side to side as he scoured the kunai grass for targets.31 Blainey’s men moved into Kaiapit No. 2 village, driving any enemy troops in their path out into the kunai to the east. Once again to the fore was Syd Graham. Despite being wounded on the previous day, he had rejoined his unit from the aid post, only to cop more wounds to his hands and chest.32

After fire from Mission Hill sent Wally Hagan’s section to ground, Fred McKittrick asked him, ‘Do you think we can do a double?’ They certainly could. The 2-inch mortar dropped a bomb on the enemy position, an isolated copse near the base of the hill.33 The platoon then cleared the area between Kaiapit No. 2 and Mission Hill. Sam Southwood’s section climbed the hill, and found the mission station on top deserted.

Meanwhile, Watson had sent out patrols to scour the battlefield for detached groups of his men and for ammunition. Soon after 0700, he finally received an ammunition resupply, much of it gathered from the other platoons and from headquarters troops. Seeing that Blainey had secured Mission Hill, Watson judged the moment right to continue the assault using Balderstone’s and Elsworthy’s sections, which were still reasonably intact. Balderstone was behind a coconut palm as his section gathered. When he came out to watch the men move into position, a bullet nicked the top of his right arm. ‘Who did that?’ he bellowed. Though not serious, the wound fired him up. Keen to finish the job, he led the section forward, inspiring the men around him as he personally tackled the Japanese machinegun positions with grenades.34 With Johnny Haine’s help, Balderstone also brought back the badly wounded John ‘Pecki’ Woods, who had been hit in the knee. Again the Japanese retreated into the kunai, unable to halt the Australians’ drive.35

Blainey’s platoon was still busy. Ron ‘Junior’ Griffiths, a Melbourne boy who looked as if he should still be at school rather than in battle, had been wounded during the previous day’s attack. But he picked himself up again and returned to the fray, guiding one section through Kaiapit No. 2 on the right of the advance while another moved through Kaiapit No. 3 on the left. Both sections joined up at Mission Hill, isolating the Japanese stragglers who remained between them and Southwood’s section up on the hill. Alf Miller shot seven with his rifle and another two with his revolver. ‘You simply could not miss,’ he later told the war correspondent Merv Weston.36

At the end, with Southwood’s section observing, directing, and supporting from the hill, Reg Hallion’s section cleared the final Japanese positions along the base of the hill. The men up top had a bird’s-eye view, and as one later observed, it was ‘like duck shooting’ as they pointed out the enemy positions in the kunai. Charlie Banks was up there alongside Wally Roach, the South Australian rifleman. Banks’ Bren was inaccurate at the ranges now required, but Roach showed why he was considered the platoon’s best marksman, dropping an enemy soldier on the run at about 300 metres. Another soldier, half hidden in the kunai, was bowled over at nearly 400 metres.

With a grandstand view of the battlefield, the men on the hill were able to direct other commandos onto the enemy troops still in the area, and around forty were killed. ‘It was almost like Flemington on Cup Day,’ was one comment. Southwood would later elaborate on the tactical advantages of such a commanding position: ‘We could see every move the Japs made when they broke into the kunai. We could pinpoint every Jap for our men, and it was slaughter from that point, very much like quail shooting.’37

After clearing two machinegun posts below Mission Hill at bayonet point, Reg Hallion was killed as he attacked a third. The section corporal, the tall, laconic John ‘Butch’ Wilson, took over command and, despite a hand wound, kept the men moving forward to clear out the remaining enemy positions. With many of the men in his section now running out of ammunition and having to rely on bayonets, Wilson had them pick up enemy rifles to use.38

At around 0800, with the hill and villages secure, Fielding’s platoon—still without Maxwell’s section—was sent in to clear out the few Japanese still scattered amid the kunai between the airfield and the villages. Tom Strika was out in front and moving along the native track. Call it intuition or a soldier’s sixth sense, but as he ducked down off the track, a shot rang out and the man behind him fell. Strika leaned forward and spotted the enemy position. ‘Here the bastards are,’ he called, turning to the others. Then he was hit in the back as if by a sledgehammer. ‘Who the fuck hit me?’ he cried out as he went down. The section moved through and cleared the position before a first aid-man ran in to help Strika, cutting half his shirt off before applying sulfa powder and a dressing.39

As Fielding’s platoon advanced, King headed for Mission Hill with his headquarters group. With Charlie Enderby and the orderly accompanying him, he reached the edge of Kaiapit No. 2, from where he could see Fred McKittrick up on Mission Hill. Then King heard shouting and saw McKittrick pointing to the kunai between the village and the hill. The kunai waved as three enemy soldiers moved towards King. Enderby bowled one over, and the others made a frantic dash to get away. King picked up a rifle that was leaning against one of the village huts and also had a shot, figuring he had succeeded when the ripples in the kunai ceased.40

Once up on the hill, King’s first priority was to get an ammunition resupply for his company. He sent a message party back to Sangan to advise that Kaiapit had been taken, and at 1130 a carrier line arrived with ammunition, a radio set, and the two PIB platoons from the fallback position. The Papuans were ordered to patrol the approach track from the west and to check the village area for stragglers.41 A makeshift hospital was set up in the old Lutheran mission station on the top of the hill, and the cooks prepared a hot meal for the men. Tex Frazier soon arrived in his Piper Cub and inspected the pre-war airstrip. He decided that it was unsuitable for the larger transports: a new strip would need to be cleared on better ground below Mission Hill. Frazier supervised the work, which basically entailed cutting back the kunai. They would trust to the sturdiness of the Dakota transports to handle uneven ground.42

Each enemy body was searched for documents and tagged by Lieutenant Maurie Davies’ intelligence section before Geoff Fielding added them to his body count. Before the 2/6th left two days later, 214 enemy dead were counted and buried; at least another fifty went uncounted. The men of the 2/16th and 2/27th Battalions, who were next to move into Kaiapit, found and buried a considerable number of additional bodies. The Australians lost fourteen men killed in action and another twenty-three wounded.

The final Australian casualty at Kaiapit was a particularly tragic one. King’s commandos had operated throughout under the strict maxim that no wounded Japanese soldier was to be left alive on the ground behind an advance. The policy was at odds with the accepted rules of warfare, but it was necessary to prevent wounded and ‘dead’ enemy soldiers causing further casualties. But King had also made it known that if one or two prisoners could be taken, they would be valuable.43 Herbert Harris, a thirty-year-old medical orderly, was trained to save lives. Now that the Australian wounded had been treated and moved to the rear, he turned his attention to a wounded enemy soldier he found lying amid the kunai. Harris had in mind King’s words about taking a prisoner, but he also saw a life he could save. As he bent to help his enemy, the Japanese detonated a grenade he had hidden on his body. He died at once, but Harris hung on for a day, long enough to talk with King. ‘You’re responsible for my condition, Sir,’ Harris told him. ‘I was trying to follow your orders, and this is what’s happened to me.’44

General Vasey arrived in a Piper Cub at around midday and walked over the corpse-strewn battlefield to Mission Hill. ‘My God, my God, my God,’ he repeated, clearly shocked by the scale of the carnage—and by the size of the force against which he had sent a single company.45 Gordon King was resting his wounded leg in a shady spot on top of the hill, but when Vasey suddenly appeared, he struggled to his feet. ‘No, no, sit down,’ Vasey told him, noting King’s injury. But King stood to talk. Vasey told him to get the first available aircraft out before adding, ‘Gordon, I promise that you’ll never be left out on a limb like this again.’ Vasey then returned to his plane, which headed back down the Markham Valley.46

The first Dakota landed at Kaiapit on the afternoon of 21 September, the day after the battle. Colonel David ‘Photo’ Hutchison brought the plane in, dodging Mission Hill and pulling up within the length of the newly cut airstrip. He took the wounded back to Nadzab. By dusk, another six transports had landed, bringing in Captain Garth Symington’s company from the 2/16th Battalion.

By any measure, the Kaiapit action was an extraordinary feat of arms by King’s men. In one stroke, it had opened up the Markham and Ramu valleys for Vasey’s troops and for Kenney’s airfields. The action had also justified the role of the independent companies in the Army structure and demonstrated the validity of King’s fire and movement maxim. Some months later, Vasey told him, ‘We were lucky, we were very lucky.’ King replied, ‘Well, if you’re inferring that what we did was luck, I don’t agree with you, Sir. Because I think we weren’t lucky, we were just bloody good.’47