17

‘I know it’s hard, son,

but it has to be done’

Markham and Ramu Valleys

June to October 1943

The reflection in the shaving mirror was the first and last time Harry Lumb saw his killer. The forty-two-year-old warrant officer with the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit had thought there were no enemy troops anywhere near the village 4 kilometres north of Kaiapit where he was sheltering. It was 7 June 1943, and Lumb was operating deep behind enemy lines, recruiting native carriers in the Markham Valley, which the Japanese nominally controlled but seldom patrolled.1 Lumb’s assailant was part of a patrol led by ‘marathon man’ Lieutenant Masamichi Kitamoto that had come up the valley from Lae, travelling light and moving fast through the foothills.2

Police sergeant Arwesor had left Lumb earlier that morning, but after hearing small-arms fire he returned to the village. The Japanese were waiting for him. They tied him to a coconut palm tree and interrogated him. From their questions, Arwesor deduced that treacherous natives had led the Japanese to Lumb. That night, he loosened his bindings and made his escape. On 13 June, when the triumphant Japanese party returned to Lae, one of the officers wore Lumb’s clothing and carried his Owen gun.3

Captain Les Howlett and Warrant Officer Peter Ryan were on another ANGAU patrol in the ranges north of the Markham Valley when they learned of Lumb’s demise. Trapped in the mountains behind Boana, they decided to cross over to the north side of the Saruwaged Range, head west and then re-cross and enter the Markham Valley away from their normal route which may be compromised. After an extraordinary journey, on a route that would later be used in the Japanese retreat from Lae, the two men, accompanied by their devoted Amyen carriers and a group of native police, re-entered the Markham Valley and followed the Irumu River down to Chivasing, on the Markham River.4

It was mid-afternoon on 21 June as Howlett and Ryan warily approached Chivasing, stopping at a coconut grove on the edge of the village while one of their native guides, Arong, went ahead to check that the village was clear. He confirmed that no Japanese were in the area and that rafts and canoes were available for the trip down the river to the Australian outpost at Kirkland’s Camp. Leaving the eight native policemen behind, Howlett and Ryan followed Arong into Chivasing. The atmosphere was uneasy, the villagers oddly aloof. Suddenly, rifles cracked and a machine gun began to chatter from a row of huts. Arong was captured while the Australians dashed for cover. Ryan made it into a creek bed, but Howlett was caught in a second volley and fell face down, dead.5

With fear driving his feet, Ryan scrambled up the other side of the creek, losing his shirt and Owen gun in the thick scrub. With bullets lancing through the undergrowth around him, he looked frantically for a hiding place—and found one, in the mud of a pig wallow. After about half an hour, he heard villagers calling out that the Japanese had gone, but having being deceived once, he stayed hidden. Then, as darkness fell, he made his way towards the Markham River. He spent the night in another mud pool, braving the crocodiles to escape the mosquitoes. Next day, he reached the river and swam across. After forcing two local villagers to take him downriver by canoe, he finally reached the Australian outpost at Kirkland’s Camp.6

Well before the Lae operation, Bena Bena, in the highlands south of the Ramu Valley, had assumed increased importance as a possible base for operations against Lae, Madang and Wewak. An infantry platoon had been flown there in January 1943 and been replaced a few months later by Major Fergus MacAdie’s 2/7th Independent Company. From Bena Bena, patrols could harass any Japanese moves into the Ramu Valley.7 The area also served as a major source of native carriers for the Australian Army.

A dummy airbase was constructed at Bena Bena, and from 4–16 June the Japanese made twelve air attacks on the area. They were also planning a ground assault. By late June, when Japanese forces occupied Kaiapit, enemy patrols had moved further up the Ramu Valley to Dumpu and Wesa. The Japanese had built a road from Madang to Bogadjim and were now extending it to Yaula, with the intention of reaching the Ramu Valley.8

On 8 July, Bruce Rofe, Con Bell and Ted Wilson were manning an observation post at Sepu, on the Ramu River west of Madang. They had just returned from a morning patrol when the post was attacked. Bell was wounded, but he and Wilson managed to clear out. Rofe was more seriously hurt: shot three times, then cut about the head with a sword. He passed out in a daze, vaguely aware of his identification tags being taken and the pain of a stab wound. When he came to, Rofe tried ineffectually to tackle his assailant, a Japanese officer. Furious, the man drew his pistol, pointed it at Rofe’s chest, and pulled the trigger. The pistol misfired, and Rofe got up and ran. Dodging shots, he plunged into the jungle and, after bathing his wounds, propped himself against a tree for the night. After reaching the main track next morning, he walked all day and then spent another night in the scrub. Late on the third day he came across some other commandos, who patched him up and made a bush stretcher for him. Once the medical officer, Captain John McInerney, arrived on 17 July, Rofe was taken back to Bena Bena and flown out to Moresby.9

On the night of 28 September, moving in total darkness, Captain David Dexter led a patrol from the 2/2nd Cavalry Commando Squadron across the eight streams of the Ramu River. Marching on a compass bearing, they reached the jungle foothills on the northern side of the valley after midnight. After moving to the Madang track west of Kesawai just after dawn, Dexter sent Arthur Birch and a native policeman east towards the occupied village to draw the enemy out. The main ambush party, arrayed in a semicircle on both sides of the track, waited as Birch and the policeman returned from Kesawai after drawing fire. Behind them, two natives led small groups of Japanese soldiers around a bend towards the ambush site. By the time the lead enemy troops were within 30 metres of the ambush site, sixty of them had rounded the bend in the track. With two Brens, nine Owens, four rifles and a liberal supply of grenades, the automatic fire ‘was like a reaper’s scythe among the Japanese’ leaving some forty-five dead and others wounded. Cyril Budd-Doyle was killed and Dexter wounded before the Australians broke contact and headed back across the Ramu. A bullet had creased Dexter’s forehead. Kaipa, a Kesawai villager, chewed leaves, added some lime, and applied the paste to the wound to stop the bleeding. He also helped carry Dexter back up to Bena Bena, quite an ordeal. Asked in later years if he still remembered Kesawai, Dexter, who had written a masterful account of the New Guinea offensives for the official history, pointed to the white scar on his forehead and replied: ‘Kesawai is indelibly marked on my mind, body and soul.’10

Since proving himself an exceptional scout during the fighting at Wau, Lieutenant Pat Dunshea had continued his exploits in the Ramu Valley, operating out of Bena Bena. With the help of his native policeman Kalamasi, Dunshea confirmed that the Japanese had built their road from the coast up towards Yaula. After the fall of Kaiapit, the three battalions of Brigadier Ivan Dougherty’s 21st Brigade had been flown in to the new airstrip there, and since 26 September Dunshea had been patrolling the area out in front of the brigade’s advance. In the early morning hours of 29 September, Dunshea hid in the kunai grass watching an Australian sentry silhouetted in the moonlight. He waited until the sentry was relieved, then followed him back to unit headquarters at Sagerak, where he surprised the unit commander and reported that the valley ahead was clear.11

From the moment the Australians flew into Nadzab, they were under insidious assault. Carried by the fragile mosquito, malaria could fell and even kill the strongest of men, and the Ramu Valley, the valley of death in the local dialect, had one of the highest incidences in the country.

The traditional treatment was with quinine, but 90 per cent of the world’s supply came from cinchona-tree plantations in Java, which was now under Japanese occupation. After the 252 Lark Force escapees ran out of quinine on New Britain in early 1942, fifty died within five weeks and most of the remainder needed hospitalisation.12 An alternative malaria suppressant had to be found or it would be impossible to maintain troops in northern Australia, let alone New Guinea. Atebrin, a synthetic version of quinine that had been developed in Germany before the war, became the Australian Army’s official antimalarial drug, and what quinine remained was reserved for treatment. Australian scientists helped develop practical methods of synthesising Atebrin and pinpointed the dosage that most effectively suppressed malaria among deployed troops. In New Guinea, wearing protective clothing, using mosquito nets, spraying, improving drainage and of course taking the bittertasting Atebrin pills became as important as any combat discipline.

Malaria is not found above elevations of about 1000 metres, but most of the fighting in New Guinea took place along the coast or in the lowlands of the Markham and Ramu Valleys. High rainfall increased the opportunities for mosquitoes to breed, so the relatively dry area around Port Moresby was less dangerous than Milne Bay and the Papuan beachheads, where malaria was rampant. From October 1942 to April 1943, malaria caused almost five times more casualties than combat did. Even that was not the full story, as most affected men had recurrences of the disease after returning to Australia.13

The highly malarial environment of the Ramu Valley almost crippled the Australian campaign. Almost 1 in 10 of the operational troops were falling ill with malaria each week, meaning that within eleven weeks almost all would be infected. There were other diseases, some—such as scrub typhus—much deadlier, but malaria accounted for 90 per cent of losses due to disease. As a result of the scientists’ studies, the daily Atebrin dose was doubled, and the infection rate fell by about two-thirds.14 For Japanese troops in New Guinea, malaria was also a serious problem. Though they had stocks of quinine, the progressive breakdown of their supply system meant that almost all frontline troops were infected with malaria, and deaths from it increased as the war went on.

The companies of the 2/14th Battalion advanced west from Kaiapit along the north side of the Ramu Valley, close to the foothills of the Finisterre Range. In its first campaign since Papua, the unit had a new leader, Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Honner, the outstanding battalion commander of the Papuan campaign. Having led the 39th Battalion at Isurava and Gona, Honner now commanded the battalion that had come to his aid in the nick of time at Isurava and had then fought alongside the 39th at Gona. On the afternoon of 4 October, the 2/14th was in the region of Wampun village when Honner decided they would stop there for the night and look for a water supply. All the men were low on water, and the native bearers had none at all to cook their rice. Captain Colin McInnes’s company was sent towards Koram to find water and to act as a screen for the rest of the battalion.

Following a divisional order, both Honner and his adjutant, Captain Stan Bisset, had not carried their bedrolls during the march, leaving both men relatively fresh at the end of the day. Despite Bisset’s protests, Honner decided to go out and see whether McInnes had found water.15 Honner was a strong-willed man and liked to be involved in everything that affected his men’s welfare, an attitude that had played a major role in his success with the 39th Battalion.

Honner headed off along the track at a cracking pace looking for McInnes’s company. Bill Bennett, Tommy Pryor and two others were in tow. Tim Moriarty watched Honner walking past, picking berries from some shrubs and eating them. ‘He’s a cool customer,’ he told his mates.16 The fresher Honner got further in front as the group headed towards a nearby village; only Pryor was able to keep up. Moving along a foot-worn local track through the tall kunai grass, they were unaware that McInnes’ company had already turned off the track and headed up into the foothills.

Honner could see troops up ahead, cutting leaves from banana trees in a patch alongside the village. Moments later a machine gun opened fire down the track, and Honner went down, shot in the groin. Pryor was hit in the chin but was able to drag his bleeding commander back into the kunai before heading back for help. He soon found Bill Bennett, but there was little they could do: the Japanese soldiers were now advancing in a line through the kunai, walking 10 metres apart. A crippled Honner hid and waited, clutching a grenade ready to use if needed.17

Back at the battalion lines, Pryor reported the situation to Captain Gerry O’Day, the D Company commander, who immediately sent Lieutenant Alan Avery’s platoon to get Honner. This was not an easy task, as Avery had to be careful not to alert the enemy party. ‘Honner, Honner,’ he called as he moved through the kunai. ‘Here, over here,’ came the reply. When Avery reached Honner, he was smothered with black ants attracted by the blood from his wound.

‘I’ll get you out now, Sir,’ Avery told him.

But Honner refused. ‘Oh no, Mister Avery. Wait a minute, we are going to put in an attack on this position.’

‘I’m sorry Sir, my orders are to bring you out.’

‘Mister Avery, who gave you that order?’

‘Captain O’Day, Sir,’ Avery replied.

‘Mister Avery, I think my orders are a bit above Captain O’Day’s,’ Honner said. ‘Get your walkie-talkie going, and get them to send up the rest of the company.’18

When the rest of the company arrived, Honner instructed the stretcher party to wait in a dry watercourse while he pointed out the enemy positions to O’Day. Two platoons went around on the right flank and captured the village while Avery’s platoon held the enemy’s attention in front. Having seen the successful attack, Honner told the waiting stretcher bearers, ‘Right, you can take me out now,’ and handed over command to Captain Ian Hamilton. After the war, Honner told O’Day that his decision to go and look for McInnes had been ‘a mistake.’19

Soon thereafter, another of Dougherty’s battalions, Lieutenant Colonel John Bishop’s 2/27th, turned north into the Finisterre Range and seized King’s Hill, overlooking Dumpu, where a rough airstrip was being prepared. Bishop’s men then moved further into the ranges, probing for the Japanese supply line from the north coast. On 11 October, as Charlie Lofberg and Frank Ranger escorted a native carrier line through the Uria River gorge, below King’s Hill, the party was fired on from above. The carriers dropped their loads and fled; Lofberg and Ranger sheltered in the gorge. The small-arms fire had come from Japanese troops who had captured a prominent knoll east of King’s Hill.

Further forward, Alan Avery had seen soldiers digging in on the position that morning. Presuming they were Australians, he called 2/14th Battalion headquarters for confirmation. Things at headquarters were a bit hectic. Around this point in the campaign, the 2/14th had no fewer than five commanding officers within two weeks. On 6 October, Major Bill Landale had arrived from Moresby to become the latest in line, and he knew that there were no Australian troops up there. When he told Brigadier Dougherty that there were Japanese troops digging in to his front, Dougherty’s reply was brief: ‘Kill ’em.’20

Up on King’s Hill, the commander of 9 Platoon, Lieutenant Noel Pallier, watched the enemy troops digging in at the other end of the ridge through his field glasses. Their motions had a rather frenzied quality. Personal entrenching tools were also not standard issue in the Australian Army. Looking harder, Pallier could see the distinctive mushroom-shaped helmets of the Japanese army. He was soon on the phone to Landale, who told him to send out a patrol to confirm his suspicions. Pallier thought the order ludicrous, but an order was an order, and he could not disobey. He told Landale he would send a patrol, but only if he went with them. ‘Why?’ Landale asked. ‘Because it’s suicide,’ Pallier said. Landale was slowly getting the message. ‘Christ, don’t do that,’ he replied.21

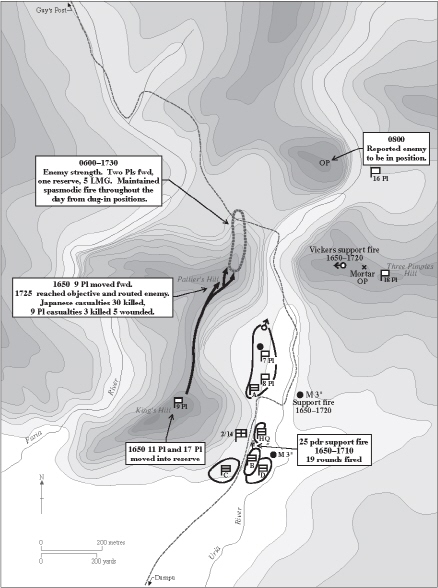

The Vickers guns down below King’s Hill opened fire on the Japanese. In response, a sniper shot dead one of the gunners, Jack Barnard. It was just before midday, and Landale had all the confirmation he needed. Stan Bisset was now given the unenviable job of organising a successful plan of attack over terrain more suited to mountain goats than infantrymen. When he scaled Three Pimples Hill on the other side of the Uria gorge to see what he was up against, the outlook was not promising. Every approach to the enemy position was steep, with towering cliffs to the north and south. Bisset arranged for a platoon, a Vickers section, and artillery and mortar observers to join him on Three Pimples Hill to provide supporting fire for an attack that would have to be made from King’s Hill.22

Pallier’s Hill: 11 October 1943

It was now approaching midday, and Dougherty was increasingly concerned about the 2/27th’s supply line. The battalion’s forward units had been shelled and were expecting a major enemy attack. The supply route had to be reopened. Dougherty was now at Landale’s headquarters and had brought Major Mert Lee with him. Lee had served the 2/27th with distinction, having received his second Military Cross for his leadership and bravery at Brigade Hill, on the Kokoda Trail. He was currently 2IC of the 2/16th Battalion; after relieving Landale of his command, Dougherty put Lee in charge of the 2/14th. His brief was clear: throw the enemy off the ridge and do it now. When Bisset next called headquarters, he was surprised to get Lee on the line. ‘Stan, it’s Mert here,’ Lee said, and proceeded to tell Bisset that his plan would go ahead as soon as the men were in position. Bisset, who knew Lee well, felt reassured by the change in command.23

Lee then ordered Gerry O’Day to get some men up onto King’s Hill to support Pallier and coordinate the assault. O’Day sent up two platoons, 11 and 17, but it would be late afternoon before they were in position. O’Day had commanded 9 Platoon in Syria, where he had led the unit up the almost-sheer crags at Jezzine. He had lost half his men that day, but here he feared Pallier might lose the lot.24

By mid-afternoon, Doug Chrisp’s section had managed to haul a Vickers gun up onto Three Pimples Hill, and Bisset had positioned it to fire across the gorge onto the forwardmost point of the enemy position. Alex ‘Jorgie’ Jorgenson fired a few bursts and estimated the range at 400 metres.25 The men of 18 Platoon would add the fire from their Brens and rifles, though at that range they could only hope to distract the enemy with the noise. Don MacEwan was also on hand to direct the 3-inch mortars back down in the valley. Heavier support would come from a Short 25-pounder gun, one of the two originally dropped at Nadzab—though it had only nineteen rounds available. With the support in place, Dougherty, Lee and the other headquarters staff anxiously watched the narrow land bridge for the first sign of Pallier’s advance.26

The situation confronting Noel Pallier was diabolical. King’s Hill and the enemy-occupied knoll were about 550 metres apart, connected by a knife-edged ridge with a small pimple about halfway along. The razorback ridge sloped down to the pimple, then up again to the summit of the enemy-held knoll, with a steep pinch at the end. The only cover on the kunai-blanketed ridge was a patch of scrub near the pimple.27

As Pallier made his plans, Japanese fire was raking King’s Hill, and despite the long range, it was hitting home. ‘Freddie’ Johns, who was alongside Pallier, took a bullet through the elbow; further forward, Mark Anderson was also hit. Watching Anderson make his way to the rear, Gordon Davies thought he might really be the lucky one among them.28 Pallier’s platoon had a fine record to uphold. Its nucleus was made up of men who had not only stormed the Jezzine fortress but had fought against overwhelming numbers at Isurava, where the platoon’s finest soldier, Bruce Kingsbury, had fallen.

Sergeant Lindsay ‘Teddy’ Bear, who had fought beside Kingsbury at Isurava, would be in the forefront of the coming assault, though he should not have been anywhere near the front line. After his gruelling trek back from Isurava, he had had bullets extracted from his knee, hip, thigh and shoulder, but two had remained in his foot. Bear had attended a sergeant’s course before returning to the platoon. Then, just before the 2/14th was flown across to Nadzab, his left foot flared up, causing so much pain he was unable to walk. Doctors investigated and found the two final bullets, which had worked their way out of his ankle to the top of the foot. After these were cut out, Bear was told it would be three to four weeks before he could return to his unit, but he slipped out of the hospital after five days. When he rejoined the platoon, Pallier told him, ‘You’re not supposed to be here.’ ‘Oh, no, I’m fine,’ Bear replied. ‘I’ll be OK.’29

Corporal Ted ‘Hi Ho’ Silver, a thirty-one-year-old Middle East veteran renowned for his expertise at sharpening bayonets, commanded 7 Section. Another veteran corporal, John ‘Bluey’ Whitechurch, led 9 Section, while Bill Parfrey was in charge of 8 Section. All three were Victorians. The platoon also included Alf Edwards, from Sydney, who had joined the Army as soon as he turned eighteen. His mother was only too happy to give her permission. ‘For chrissakes get him into the Army,’ she said. ‘He’s driving me crazy.’ Edwards joined the 2/14th on the Atherton Tablelands in mid-1943.30 Another newcomer was Hugh ‘Lofty’ Norton, a strapping lad whom Pallier had helped train at Bathurst. Spying his tall frame among the newly arrived reinforcements, Pallier asked him to come over to his platoon and bring any reliable mates—one of whom was Alf Edwards.31 Ernest ‘Lofty’ Back was the real character in the platoon. When the tall, laconic Queensland shearer first joined up, an officer had given the new recruits a talk about the history of the 2/14th, covering the battles in Syria, on the Kokoda Trail, and at Gona. ‘Any questions?’ he asked as he finished. Lofty piped up: ‘I’d just like to say we’re due for a win.’32

Pallier had three options for the assault. On the left of the ridge, his men would be out of sight of the supporting fire, along the top they would be too exposed, but on the right there was a better chance. The men would be moving in the late afternoon shadows and in full view of the men providing supporting fire from Three Pimples Hill. The approach would need to be in single file. Silver’s section would lead the way, with Pallier’s small headquarters group next in line, followed by Whitechurch’s and Parfrey’s sections. Pallier decided to put his own support weapons, the 2-inch mortar and a Bren gun, on the pimple-like knoll in the centre of the ridge.33

The terrain also made it difficult for the Japanese to put up an effective defence. The enemy position was angled back towards the north, meaning that Pallier’s approach along the southern side of the ridge could be seen only from the most forward weapon pit. If Pallier had taken his men forward along the northern side of the ridge or along the top, they would have been subject to fire from most of the enemy positions.

Mert Lee had a final discussion with Pallier over the phone and told him he must take the position before dark. More enemy troops were expected that night: if Pallier failed, the ridge would become an impregnable fortress in the heart of the Australian brigade. ‘Of course you understand it’s do or die,’ were Lee’s final words. Pallier swallowed hard. ‘Right, Sir,’ he replied.34

The late-afternoon clouds were closing in as Pallier gathered his twenty-nine men and explained the plan. He mentioned the 25-pounder, the mortars and the Vickers support before stressing, ‘Let’s use that support.’ Pallier’s batman, Johnny Cobble, stepped forward and asked, ‘Skipper, can I go on the supporting Bren?’ He was given the job. Meanwhile, Gerry O’Day had finally reached the top of King’s Hill with his men. ‘I’m on the way, boss,’ Pallier told him. Knowing the risk they faced, Pallier’s men shook hands and wished each other luck. Lofty Back and Johnny Cobble were both bushies from western Queensland, where Back had been a shearer. ‘See you at the Winton races,’ Back said to his mate as they set off.35

At 1650, the Short 25-pounder opened fire down in the valley, the signal for the platoon to move forward. Pallier had spied a washed-out gully just off King’s Hill: his sections got organised there before moving out in single file along the side of the ridge. Scrambling across the steep slope through the sparse scrub, Hi Ho Silver took the lead, digging in his boot heels to gain purchase. The others followed in his very footsteps and reached the pimple halfway along the ridge unmolested. The support group—Cobble with the Bren, Bill Patterson with the 2-inch mortar, and Bobby Malcolm with an EY rifle—stopped and remained there while the others went on.

The 25-pounder was firing over open sights and an observer up on Three Pimples Hill was calling back the fall of shot. The gun’s lightened carriage and lack of a base plate meant it was jumping all over the place, so it had to be realigned after every shot.36 As Pallier’s men clambered around the pimple, he was counting the shells—one a minute—knowing he had just nineteen minutes to get as close as possible to his objective. The Australians heard a whoosh as each shell went over, then a thump when it hit the ridge ahead of them. Pallier imagined the enemy defenders hunkered down in their foxholes, just getting ready to have another look when the next shell arrived. As the nineteenth shell was fired, a cry of ‘There she goes!’ rang out. Now it was a climb up into the face of the enemy. The 3-inch mortar continued firing, but its high trajectory and the narrow target area made aiming difficult, and most of the bombs fell short or overshot into the gorge beyond.

The Vickers gun across the gorge continued to give supporting fire right up until the attackers reached the crest. The Vickers barrel was locked to fire along a fixed line: it could be shifted a degree or so to left or right by giving the firing handles a slap of the palm. Jorgie Jorgenson and Jack Cunningham shared the work behind the gun, firing at right angles to the advancing men. Stan Bisset carefully watched the enemy positions for any movement, knowing how vital it was to keep the Japanese soldiers’ heads down until the Aussies could close with them. The riflemen and Bren gunners added their firepower, but at that range they felt powerless to help. Some men just shook their fists at their enemy across the gorge, hoping to keep the defenders distracted. The considerable enemy fire directed back at Three Pimples Hill was largely ineffective, and it diverted the Japanese gunners’ attention from Pallier’s men as they climbed, watching the Vickers rounds churning up the earth in front of them.

To Pallier’s amazement, there was still no enemy fire as his men reached the final pinch up to the knoll. Here the ridge was at its worst and very steep: one misstep could send a man hurtling into the gorge below. A few Japanese rifle shots rang out, followed by a machinegun burst, and soon the fire became one continuous roar as the defenders, suddenly noticing the men on the small pimple, targeted them with a vengeance. With the assault sections hidden by the slope up to the summit, the defenders seem to have thought the supporting section were the only attackers. First hit was Johnny Cobble: he would never make it to the Winton races. Then Bill Patterson was shot dead, and Bob Malcolm, between them, knew he was next in line. He took what cover he could behind the small pimple, hugging the ground as a First World War Digger had once told him to. He would survive.37

Further back on King’s Hill, O’Day’s men could only watch. Tim Moriarty was having a smoke. He turned to Bill Leslie and said, ‘They’ve got hummingbirds up here like back home.’ ‘Get down,’ said Leslie, ‘those are bullets.’ ‘Jack’ O’Dea was shot in the face, and though the men did what they could for him, they could not save his life. As they would continue to prove throughout the campaign, the Japanese riflemen were deadly shots at long range.38

Pallier’s men fanned out under the cover of the slope below the enemy positions. Hi Ho Silver gave his men their orders. To Johnny Twine: ‘Now Johnny, you stop at my right hand with the Owen.’ Then, to Billy Howarth: ‘You keep on my left arm with that Owen gun, Billy.’ Then, to both of them, ‘And don’t you move from there.’39 In the centre, Pallier had his headquarters group, including Teddy Bear. On the left flank was Bluey Whitechurch with his section, Alf Edwards and Lofty Norton among them. Bill Parfrey’s section would come in behind once the lead sections had climbed up.

Without making an order of it, Pallier calmly said, ‘Fix bayonets if you like.’ Most of the men did, the metallic clash of the bayonet lugs on the rifle barrels echoing across the hill.40 Pallier also carried a rifle to help avoid being recognised as an officer, but he did not carry a bayonet. Across on Three Pimples Hill, Stan Bisset watched through his binoculars as the men formed up to tackle the final few metres of the incline. He cut the supporting fire as they began to climb, then told the Vickers crew to move the gun to a second firing position off to the right. From there it could fire further back along the ridge, across the path of any retreating or reinforcing enemy troops.41

Finally seeing the Australians looming up on their position, the Japanese defenders raised their heads from their weapon pits and rolled grenades down on the attackers. There were so many grenades, Pallier recalled, that it was as if a sugar-bag full had been emptied onto them. But the slope was so steep that most grenades rolled too far before detonating. Others landed above the Australians, rolled down among them, and were speeded on by a vigorous push or kick. Pallier copped a grenade blast on his left leg but kept going. He hardly felt it at the time, but would later find his left knee badly damaged and shrapnel in his leg and around his ribs.42

Hi Ho Silver hauled himself up the slope while on his right Johnny Twine struggled to get a grip on the loosened surface. ‘It’s hard Hi Ho,’ he gasped. Struggling himself, Silver turned to him and said, ‘I know it’s hard, son, but it has to be done.’ At the same moment a grenade landed in the dirt next to Silver’s leg; he kicked it away while still urging Twine on.43

One of Whitechurch’s men on the left copped a grenade blast, while another almost slid off the ridge as he dodged other grenades. Alf Edwards would never forget the sound of enemy grenades being banged against helmets or rocks to initiate the striker, or the Australians’ frantic attempts to brush them away as they landed.44 Lofty Norton later said: ‘The Japs began to jabber and an avalanche of grenades rained down on us . . . we were very lucky to suffer so few casualties from them. If they had been as good as our own grenades are, half of us would have been killed.45

But within minutes they were hurling their own grenades up into the Japanese positions as they scrambled the last few metres to the summit. The supporting shellfire had badly loosened the surface, so the men had to dig in hard with the toes of their boots to get a firm foothold. Somehow they found the strength and will and drove themselves on, shouting, ‘We’ll get you bastards . . . We’ll make you sorry.’46

Reaching the top first, Teddy Bear and Hi Ho Silver got their heads and shoulders over the crest and fired everything they had at the defenders. Bear worked his rifle bolt in a blur, while Silver emptied his Owen gun magazine in one withering burst. Then, using the split second they had gained with that opening salvo, they both scrambled over the top. Johnny Twine, who was right behind Bear and Silver, watched as a defender in the critical first weapon pit tried to fire at each in turn, and they at him—all in vain, because all three had already emptied their magazines. Though wounded in the back by a grenade blast moments earlier, Bear reacted first, lunging with his bayonet as he rushed the pit, hurling the first defender aside, then turning back to the next one and crashing the butt of his rifle down on him. Bear and Silver then reloaded and dashed forward.47 The Japanese weapon pits were echeloned back along the top of the ridge, and both men, with Silver’s section behind, moved from one position to the next clearing out the defenders.

Teddy Bear was a big man and very strong. At least twice more he thrust his rifle down onto cowering defenders, skewering them with the bayonet and hurling them aside. Back on King’s Hill, Gerry O’Day stared in amazement at Bear’s silhouette tossing enemy soldiers off his bayonet like sheaves of wheat off a pitchfork. It was a sight that would stay with him for the rest of his life.48 For the defenders, their weapon pits became their graves. Some sat in the pits with their backs to the oncoming Australians, throwing grenades over their shoulders, while others fixed their own bayonets and came out to fight. But the narrowness of the ridge meant they could do so only one or two at a time, and Bear and Silver were unstoppable.

It was a terrible business having to use the bayonet, but Pallier’s men had the red mist in their eyes and one goal in their minds: they had to take the ridge, and nothing would stand in their way. Bear later told his son-in-law that he ‘was like a madman.’49 He did what needed to be done, and he had the skill and courage to do it: he was surely one of the finest soldiers Australia ever put into the field, in any war.

As the rest of Silver’s section reached the top, the left-hand section also charged in after the ginger-haired Whitechurch, who was firing his Owen gun from the hip. Johnny Twine, who had watched Bear and Silver race ahead, thought Whitechurch’s section must have had an easier climb. The men streamed out onto the hill, cutting in front of those of Silver’s section.50 The incline on the left was indeed somewhat easier and had not been churned up by the supporting fire, but that flank was also open to counter-fire from the defenders further back along the crest. Rather than attacking the Japanese lines along the top of the crest, as Silver’s section was doing, Whitechurch’s section was arriving across their front. For the Japanese soldiers facing the onslaught led by Bear and Silver, the sudden appearance of another group of screaming attackers coming directly at them from the flank was too much, and they broke. Whitechurch later described the outcome: ‘We could see them now and opened fire on their heads as they bobbed up above their foxholes . . . Somebody gave a shrill blood-curdling yell that startled even us, and was partly responsible for some of the enemy running headlong down the ridge in panic. Unable to stop at the edge of the cliff, they plunged to their doom hundreds of feet below.’51

Lofty Norton remembered: ‘Bluey Whitechurch, our section leader, let out a terrific yell: “Come on you yellow so and so’s, we’re Australians and we’re going to kill every one of you” . . . we took up the yell and got stuck into the Nips. I think the yell must have unnerved a lot of them. One Nip stood up in his foxhole; I think he must have been trying to escape. Every chap who saw him let him have it and I saw his tin hat jump up in the air at the impact of the bullets against his body.’52

Watching from down in the valley, Alan Avery saw about ten defenders run straight over the cliff. Having arrived in the night and worked all day preparing their positions, the defenders may not have known of the cliffs further down the ridge side.53 Those who did not fall to their deaths fled in panic down the access track to the east and sprinted off into the jungle as the Vickers gun on Three Pimples Hill sprayed deadly fire across their path.

Back on the crest, Gordon Davies came running over to Pallier to tell him, ‘Parfrey’s been hit.’ He had been badly shot through the upper arm. Pallier told Davies to instruct Lofty Back to take over the section and attack. Soon there came a blood-curdling yell that startled everyone. It was Back. ‘Come on, come on,’ he urged—and then he was dead.54 Not all the Japanese had fled: one had targeted the section leader. Like his mate Johnny Cobble, Lofty Back wouldn’t make the Winton races.

Behind Whitechurch, Alf Edwards joined in the screaming as he reached the top. Spotting the head of one defender above his weapon pit, he dropped to one knee and fired, the shot sending a helmet flying as it found its mark. Then, as he looked for Whitechurch, Edwards was struck in the upper right arm as if by a sledgehammer. He fell back down the slope. ‘I went arse over head and I sort of slid down the side of it,’ he later recalled. When he stopped, his rifle clattered into him from above, the bayonet hard up against his neck, the barrel pointed at his head. Claude Lamport was dressing his fractured arm when a couple of other men arrived. Hi Ho Silver called down: ‘Come on, you lot, it doesn’t take half a dozen to look after him.’55

Up on top, a machine gun opened fire from further back along the ridge and the Australians hit the ground, clinging to the knoll they had just taken. Teddy Bear had finally fallen, shot in the knee. He was lying above and to the left of Pallier, in the path of a machine gun. Bear knew he was in trouble. ‘They’re on to me, Noel,’ he called to Pallier. Seeing his sergeant’s plight, Pallier told Bear to roll towards him. Bear did so and survived; he later named his son Noel.56

Pallier had also been hit, with a bullet wound to his groin. Apart from the machinegun fire now raking the exposed crest of the knoll, he was also concerned about an enemy counterattack. Seeking cover, the Australians pulled enemy bodies from the weapon pits and greedily gulped what water they could find from enemy canteens.57

As Alf Edwards made his way back to the crest of the knoll he passed Bill Parfrey, who was lying on his belly with shrapnel wounds to his legs. ‘Like a smoke, Bill?’ was all he could offer. Pallier, clearly in considerable pain from his wounds, told Edwards, ‘A job well done, son. You made a name for the platoon. Tell Captain O’Day to get something up here in case of counterattack.’58

For Pallier, the fight was over. He handed over command to Jack Arnold, who pushed further down the track off the end of the hill. Back on King’s Hill, Gerry O’Day watched the wounded men returning along the ridge. ‘Keep going, keep going,’ Teddy Bear kept telling Edwards as they made their way back. At the pimple, Edwards saw Bob Malcolm, who ‘was white as a bloody ghost.’ When Edwards asked what had happened, Malcolm just pointed to the bodies of Cobble and Patterson. ‘There they are,’ was all he said.59 O’Day sent a platoon forward to relieve what was left of Pallier’s on what was now known as Pallier’s Hill.

Down in the gorge below, the men of the supply train escort waited anxiously for news of the battle that had swept across the ridge above them. That night they took it in turns to watch the track across the river. But nobody came. Any Japanese who had not fled from the ridge above lay dead at their posts or broken on the rocks at the bottom of the gorge.60