18

‘They didn’t know the country

was impassable’

Finschhafen to Saidor

September 1943 to February 1944

This wasn’t the way you were meant to win a battle. With a brigade of some 2500 highly trained infantrymen and supporting arms deployed, it shouldn’t have come down to a single soldier, no matter how able he was or how brave. The battalion commander had given the order to pull out, but as Sergeant Tom ‘Diver’ Derrick hauled himself higher up the ridge in the fading light, he knew there was no going back. Behind him, five enemy posts had already been knocked out and more lay ahead. Taking a haversack of grenades with the pins fixed so they could be pulled easily, Derrick kept on clambering across the precipitous slope, at times hanging onto vines as he threw the grenades unerringly into the apertures of the enemy bunkers just moments before the fuses ran down. Behind him the Bren gunners fired over his head, while further back along the narrow spur the rest of the platoon made as much noise as possible to distract attention from Derrick. Derrick cleared three more bunkers before reaching a kunai patch below the ridge crest. The hold was tenuous, but the Australians were now in dead ground below the second line of enemy defences.1 He didn’t know it then and would never admit it afterwards, but Tom Derrick had single-handedly driven the Japanese Army from the mountain fortress that was Sattelberg Mission.

After the rapid victory at Lae, further opportunities beckoned for the Australians. While Major General Vasey’s men headed west to clear the Ramu Valley and threaten Madang, Brigadier Gordon Windeyer’s 20th Brigade jumped back on the landing craft and headed to Finschhafen, at the eastern end of the Huon Peninsula. Finschhafen was a Lutheran mission station that not only had an excellent sheltered anchorage but was a fine site for a major airfield. It would serve as a staging post for further operations on New Britain, just 100 kilometres across the Vitiaz Strait, and west towards Madang and beyond—more steps along the road to Tokyo.

Aware that the fall of Lae was imminent, the Japanese command had been building up troops in Finschhafen. Two battalions from the 80th Regiment, an artillery battalion from the 26th Field Artillery Regiment and the 7th Naval Base Force, all under the command of Major General Eizo Yamada, had travelled by barge down the coast from Madang, and had arrived by 15 September, a week ahead of Windeyer’s brigade. Another 800 troops from the 238th Regiment who had been en route to Lae were also now in Finschhafen. Added to the 400 men of the 85th Naval Garrison already there and Yamada’s 2800, the Japanese now had about 4000 men facing the 9th Division—a considerable force. In addition, 3080 men, mainly from the 79th Regiment were also on the way from Madang, accompanied by Lieutenant General Shigeru Katagiri, the 20th Division commander. As they marched overland from Sio and Sialum, these soldiers passed the exhausted and starving remnants of the 51st Division at Kiari. They did not know it then, but they were glimpsing their own future.2

Windeyer’s brigade landed north of Finschhafen before dawn on 22 September. Lieutenant Colonel Noel Simpson’s 2/17th and Lieutenant Colonel George Colvin’s 2/13th Battalion made the main landings at Scarlet Beach, between the Song River and Siki Creek, about 9 kilometres north of Finschhafen. Confused in the darkness, however, the first two waves of the landing force came ashore further south, at Siki Cove. The commander of John Dickson’s LST grounded the craft on a reef and the men left the ramp into water four metres deep. ‘He dipped us like sheep,’ Dickson recalled.3 The landing was difficult, but resistance was sporadic, the coastal defenders soon withdrawing to stronger positions in the foothills at Katika. Having secured the beachhead by day’s end, Windeyer’s troops then pushed south, closing up to the steep banks of the Bumi River. The main enemy defences were behind the river in Salankaua Plantation, protected on the inland flank by a confused tangle of jungle-covered ridges and ravines. The Japanese had selected the positions well, using the terrain to their advantage. As Peter Hemery wrote: ‘The only thing left out of his calculations was the AIF’s ignorance. They didn’t know the country was impassable.’4

When his brigade met with serious resistance along the coast, Windeyer sent troops inland. Two companies from Lieutenant Colonel Colin Grace’s 2/15th Battalion hacked through the tangled terrain on compass bearings, creating a narrow winding track. Under cover of machinegun fire, the men then crossed the Bumi River further upstream at a waist-deep ford. ‘We grabbed our Brens and went for the lick of our lives,’ Lieutenant James Dunn later wrote. ‘. . . Some of us did submarine sprints. Others flew across the twenty-five yards of water so fast they hardly got their boots wet.’5 The enemy’s resistance was sporadic, hindered by the almost sheer riverbank below its positions. However, the Australians would now have to climb that obstacle.

Colvin’s 2/13th Battalion then passed through, Captain Edwin Handley’s company leading, the men crossing the river one at a time and scrambling up the opposite bank on hands and knees.6 Climbing cliffs and crossing two sets of ridges, they were held up by the final ridge overlooking the coastal strip, the heavily fortified Kakakog heights. Colvin’s men fought their way up the steep ridges, using one hand to hold on and the other to fire their weapon. As Hemery observed, ‘It was literally a jungle Gallipoli.’7 Having hacked their way up the ridge, the Australians screamed and howled as they broke out across the crest, putting the Japanese defenders to flight and capturing three 13-mm automatic cannon. Mortar sergeant Bert Chowne, just twenty-three and already a distinguished veteran of Tobruk and El Alamein, dragged the signal wire up through the jungle and then directed mortar fire onto the enemy positions. He was awarded a Military Medal for that action and commissioned as an officer at the end of the campaign. Even higher honours were in store.

On the morning of 1 October, American light bombers made low-level attacks on Kakakog. As ‘they came up from their pass you’d hear a solid crash of sound,’ Hemery wrote. He then watched as RAAF Vultee Vengeance dive bombers arrived: ‘They screamed down just over our heads in near vertical dives . . . the jungle heaving skywards in great gobs like bubbles bursting in a sea of green lava.’8 For at least one of these pilots from RAAF No. 24 Squadron, vengeance was indeed sweet. Flying Officer William Hewett had been shot down while serving with the same squadron, piloting a Wirraway against Zeros during the dark early days over Rabaul.9

The air attacks were followed by a barrage of 600 rounds from the 2/12th Field Regiment’s 25-pounders. The dazed defenders fought back but gave way throughout the day to the hardened infantrymen, who had moved in under the barrage. More shelling, some of it directed by Colvin, helped two of his companies to get forward and make the final assault. The first thrust was stopped by sheer cliffs and intense fire from the heights; Colvin’s men were trapped in the confined gully below. The axis of the attack then swung around to the left, along the edge of Salankaua Plantation. Two platoons from Captain Paul Deschamps’ company formed up in the bed of Ilebbe Creek under Sergeant Geoff Crawford. They then rushed four machinegun positions, with Crawford and a Bren gunner, Fred Rolfe, to the fore. Both men were badly wounded.10 Les Clothier, who led the attack on the right, wrote of the savagery inherent in such fighting: ‘One bloke lay doggo pretending dead but as I passed him he opened his eyes so I bayoneted the animal.’ Five of the eight men in Clothier’s section were casualties, including Clothier himself, who also wrote, ‘I hope Mum don’t worry too much about my little Blighty.’11 Deschamps was also wounded; in the end Lieutenant Ken Hall was the only officer who emerged unscathed, though his batman and sergeant were both wounded beside him. It would happen again later in the campaign.12

On Deschamps’ right, Captain Bruce Cribb’s company also struggled to make headway. As soon as they crossed the creek the men came under heavy fire, some of it from Australian artillery shells hitting the tree tops. Twice that night the Japanese counterattacked, but now they were only masking the final withdrawal. When the diggers advanced the next morning, Finschhafen was deserted, ‘as bare of Japs as Martin Place’, in the centre of Sydney.13

On 2 October, Windeyer’s brigade met up with the 22nd Battalion, which had fought its way along the coast from Lae. The Allies now had access to the finest natural harbour on the New Guinea coastline—and, soon, one of the largest airbases in the South Pacific. Rabaul, the linchpin of Japanese operations in the region, was now well within striking range. For now, however, Allied naval forces off Finschhafen were also within striking range of the Japanese: they were hammered from the air and then struck from below, the destroyer USS Henley torpedoed and sunk by a submarine on 3 October.

Although Finschhafen had fallen, it was by no means secure. Control of the dominating heights around the old rest station at Sattelberg (Saddle Mountain in German), 8 kilometres inland from Scarlet Beach, would be needed before Finschhafen could be used as an Allied base. Soon after landing, the 2/17th Battalion had pushed up into the hills below Sattelberg, only to find the area strongly held. In the early hours of 30 September, this force was relieved by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Joshua’s 2/43rd Battalion, which put ashore from three US destroyer transports; the 2/17th rejoined the rest of 20th Brigade for the final operations against Finschhafen. The Australian command had wanted more than a battalion deployed here but had been stymied by the inability of the Americans to organise the necessary transport either for carrying the troops or for maintaining them. General MacArthur was hampered in his decisions by poor intelligence, which had considerably underestimated Japanese strength.

Joshua’s men were soon in contact with enemy troops on the Sattelberg Road. On 1 October, two platoons from Captain Eric Grant’s company and a platoon from the Papuan Infantry Battalion were cut off at Jivevaneng. Attacks by two other companies failed to break through, but a PIB sergeant, Terry Scott-Holland, was finally guided in by two Papuans who had been sent out of the perimeter. These three led Grant’s men out on the morning of 4 October, only hours before the two relieving companies finally broke through. The previous day, two companies from Simpson’s 2/17th were sent up a rough track, ironically named Easy Street, to capture Kumawa, south of Jivevaneng. This action cut the main Japanese line of retreat from Finschhafen and also helped support Grace’s 2/15th Battalion, which took over at Kumawa. The task of pushing through a jeep track would take longer.

At Jivevaneng on 9 October, Captain Tom Sheldon’s company from the 2/17th attacked a key knoll straddling the road about 400 metres west of the village. Sheldon’s men moved around the north flank of the position via a deep ravine. Artillery then opened up and, guided by PIB scouts, Lieutenant Robert Bennie’s platoon moved up a very steep spur to within 10 metres. The rain helped to conceal the approach and deaden the sound. As Ron Stanton recalled, ‘we left the jungle and were almost on top of the enemy when all hell broke loose . . . the rain suddenly stopped and we charged up a very steep slope on our hands and knees midst a shower of grenades from the Japs.’ Bennie’s men broke through to the road and crossed it under machinegun fire from the flank. ‘Clarrie’ Brooks moved up the road, firing his Bren from the hip, and silenced the enemy position. Sheldon’s two other platoons followed and consolidated on the knoll.14

The sound of bugles soon heralded an enemy counterattack. ‘Peering down the hill, I felt my heart pound as I saw the points of bayonets moving slowly forward,’ Harry Wells later wrote. Wells opened fire with his Owen gun ‘and the sweet ecstasy of sound that came from it brought comfort beyond expression.’15 The Bren and Owen fire, and grenades rolled down the slope, stopped the Japanese—though not without loss. Fred Peters, who occupied a Bren gun post 5 metres out in front of the main defences, fell to a sniper, as did Tom Brown when he went out to recover Peters’ body after dusk. A second attack was also made, and the advantage of higher ground and better grenades told for the Australians. In Bennie’s words, the enemy ‘yelled when the grenades went down.’ Next morning, the Japanese tried to blast Sheldon’s men off the knoll, which was now stripped of cover. Bennie counted fifty-three shells; three of his men were killed. Sheldon was among the wounded, hit in the knee. Evacuated, he handed over command to the resourceful Bennie. The shelling was the prelude to additional counterattacks, five that day.16

That same day, the headquarters of Major General George Wootten’s 9th Division arrived, accompanied by that of Brigadier Bernard Evans’ 24th Brigade. However, despite the introduction of Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Gallasch’s 2/3rd Pioneer Battalion, troops were still spread thin: the Australian lines now stretched from south of Finschhafen across the Song River to Bonga in the north, and west into the foothills of the Cromwell Mountains.

On 13 October, Captain Bill Angus’ company from the 2/15th would attack from Kumawa, looking to evict the Japanese from strong positions across the track further west. It was a blind attack, as the thick undergrowth prevented any reconnaissance and heavy preliminary fire failed to elicit a response from the well-concealed enemy positions. Sergeant Alick Else, in command of 7 Platoon on the left, could not stop looking down at his watch as the artillery and mortar support thundered down before the 0900 start time. When Angus whispered the awaited command, a simple ‘Forward,’ the men began moving up the steep slope through the dense cane. Ten metres from the crest, Else watched as ‘all hell was let loose from the Nips.’17

Bill ‘Dad’ Woods, two days short of his thirty-third birthday, led the section in on the left. It was cut to pieces. Soon five men were dead or dying and another down, leaving only Woods and Len Hinton to clear out the enemy machinegun post with grenades. The rest of the platoon started to yell, a collective howl of anger and determination. In the heat of battle, Woods had the presence of mind to collect and use ten grenades from his fallen men and to swap his rifle for an Owen gun. Hinton handed recovered Owen magazines up to Woods, who fired some fifteen of them at the second machinegun post. This enabled Doug Smales to get forward with his section and get stuck into the remaining positions. ‘Both his and Dad’s clothing are bullet ridden,’ Else observed, before ordering the reserve section up. The men crossed the track as one and gained the first line of defence. Else later wrote, ‘Smithy has his ankle blown off and before he falls he shoots three Nips with his Owen.’ Meanwhile, Woods continued to fight for those who could no longer do so. But Else’s platoon had lost two-thirds of its men, and the survivors, who were almost out of ammunition, lay down among the dead. Angus now ordered 9 Platoon forward. ‘Under a withering hail of lead,’ they advanced through Else’s remnants to drive the Japanese from the rear posts. ‘Half past nine and the position is ours,’ Else wrote. One of the outfought defenders later recalled, ‘With tears in our eyes we had to withdraw.’ Alick Else’s tears would come later: during the assault, he had seen his younger brother Cyril killed.18

Japanese reinforcements were also arriving. General Katagiri reached the front on the same day as General Wootten and immediately planned an offensive using both the 79th and 80th Regiments. Katagiri’s plan included two diversionary attacks from the north and a bold amphibious raid on Scarlet Beach. His main ground attack would be directed down the Sattelberg Road. The challenges Katagiri faced were typified by the method he used to communicate with his sub-units. In a throwback to another era, the date of the attack would be confirmed by a fire lit on the Sattelberg heights. Unbeknown to Katagiri, the Australians had captured his plans; they were confident the attacks could be held. At dawn on 16 October, the Japanese struck the 2/17th at Jivevaneng and, though attacks continued throughout the day, the Australians maintained their positions.

Next morning, the Japanese made an audacious attempt to land three barges full of infantry at Scarlet Beach. Like the kamikaze pilots of later days, Lieutenant Kazuyuki Sugino’s men drank a toast of sake before leaving Nambariwa, 5 kilometres southeast of Sio, on what was virtually a suicide mission. Of the seven barges that set out, only three made it along the coast to Finschhafen.19 Shielded by heavy rain, these barges were not sighted until they neared the mouth of the Song River, where they were too low in the water to be targeted by the Bofors anti-aircraft gun on the beach. A 37-mm anti-tank gun further down the beach crashed a shell into one of the barges, forcing it to retire to the north, but the other two barges kept on and made landfall.

Nathan Van Noy, an engineer with the US 532nd Boat and Shore Regiment, was manning a .50-calibre Browning machine gun only 15 metres from where the two barges beached. His loader, Stephen Popa, was on watch and woke Van Noy with a nudge: ‘Heh, Junior. The damn Japs are comin’.’ Waiting until the barges were committed to landing, Van Noy directed a withering hail of fire at the disembarking raiders. Even after a grenade exploded in the gun pit, shattering his leg and wounding Popa, Van Noy ignored the calls to withdraw. He continued to flay the raiding party, pinning Sugino’s men down at the water’s edge. A second grenade struck another hammer blow to his legs, but still Van Noy kept shooting. Then a third grenade found its mark. The gallant young man died with his finger hooked around the trigger of the Browning, whose ammunition was all spent. Out in front of the barges, thirty-nine Japanese raiders lay dead, most of them killed by Van Noy. He was awarded the Medal of Honor, his country’s highest military decoration.20

Though none of Sugino’s men got beyond the shoreline, Lieutenant General Adachi gave them a citation and a stirring obituary. Though divorced from reality, Adachi’s report provides insight into the expectations he had of his troops. They ‘fought so furiously it would make even the Gods cry,’ he wrote, and had ‘demonstrated the unique and peerless spiritual superiority of the Imperial Army.’21 Sergeant Masatsugu Ogawa, serving with the 79th Regiment, gave a more plausible description of what it was like going up against the superior firepower that the Australian infantry could deploy. ‘You can’t raise your head,’ he said. ‘When the bullets come low you can’t move. Your back is heated by the bullets. You can’t fire your single-shot, bolt-action Type-38 infantry rifle. You’d feel too absurd.’22

Across the Song River to the north, the main thrust of the Japanese attack had more success, infiltrating the positions of Colonel Gallasch’s Pioneers. Lieutenant Colonel Colin Norman’s 2/28th Battalion, the Busu River veterans, moved up to reinforce the position. However, Brigadier Evans was still worried that his brigade was too dispersed, so he pulled some companies back to protect Scarlet Beach. The Bofors gunners also proved effective, at times firing over open sights to hold back the Japanese thrusts, which in some places reached the coast. A panicked Evans now gave up a dominant position at Katika to reinforce his beachhead. Like others before him, Evans had been unable to adjust his tactics to the terrain and make it work for him instead of against him. In this situation, maintaining unbroken defensive lines was not as critical as holding the higher ground. Nonetheless, Scarlet Beach was secure. Not so Evans, who was relieved of his command on 1 November.

With landing barges the only means of transporting supplies from the main Japanese base at Wewak, and Allied torpedo boats and aircraft on the prowl along the coast, the defenders were in dire straits from food shortages. One of the 80th Regiment officers at Sattelberg wrote: ‘My one wish is to defeat Americans and get their good food. However, with our casualties from enemy shells how in hell am I going to survive through this.’ Things only got worse. On 12 November he wrote: ‘Have enough rations for one meal—will have to make it do three. We are always hungry and find it hard to get along.’ Five days later, he was killed in action.23

On 13 October, another 80th Regiment soldier noted the torments of Sattelberg but also demonstrated an almost spiritual belief in his mission: ‘Where could there be such hardship outside of war? We cannot even build fires to keep ourselves warm when drenched in the rain and shivering. We are constantly attacked by malaria mosquitoes and suffering from poisonous insects. The trench, which is the safest place, is filled with rain water . . . If I should be so unfortunate as to die from an enemy bullet, my soul will positively chew to death the American forces.’ On 22 October he wrote: ‘I eat potatoes and live in a hole and cannot speak in a loud voice. I live the life of a mud rat or some similar creature.’ Nine days later: ‘I shall die fighting and praying for the prosperity of the empire.’ On 15 November he made his final entry: ‘The platoon leader told us about the suicide squad.’24

One Japanese officer at Sattelberg showed an almost unbelievable resolve, writing on 4 November: ‘We’ve been without rations for a month . . . We have eaten bananas, stems and roots, plantation trees, bamboo shoots, grass and flowering ferns, in fact, everything up to leaves of trees that could be eaten . . . this is splendid training for us.’25 But not all saw suffering as desirable. ‘How do we of the Imperial Army, enjoy rationing?’ First Lieutenant Uchimura observed. ‘As we have no rations we fight while only eating grass.’ ‘We are hoping to depart from this southern battle front, but this unforgettable existence in the jungle seems never to end,’ another soldier wrote. ‘We dream of good food, having only potatoes day in and day out. Friends die every day. I want to return alive from this war. When I am alone I always think of my family in Japan.’26

An engineering company commander with the 20th Division, Lieutenant Toshiro Kuroki, knew just how badly the higher command had let the troops down. On 16 November, he wrote: ‘Since our arrival, 11 November, we have had hardly any rice. We added a few potatoes to what rice we’ve had and continued to fight. We have an army, a division, and an area army, with a C in C, a div commander, a C of S, a director of intelligence, and what have you, but in the front lines we have to contend with a rotten supply situation, and live a dog’s life on potatoes.’ The next day he continued: ‘You won’t find many smiling faces among the men in the ranks in New Guinea. They are always hungry; every other word has something to do with eating . . . The men in the rear, whose biggest job is talking, know nothing about the soldiers on the hills, in the valleys, and in the native villages of the forward areas, dying off like flies. The stupid fools!’27

The Japanese were hungry, but they would defend Sattelberg, which, as Official Historian Gavin Long wrote, ‘looks like a natural fortress, whose walls rise steeply from the surrounding mountains.’ Wootten’s third brigade, Brigadier David ‘Torpy’ Whitehead’s 26th, now entered the fray. A squadron of nine Matilda tanks from the 1st Tank Battalion had also arrived. At Jivevaneng on 17 November, the tanks and the South Australian 2/48th Battalion set off towards Sattelberg along the road. On their right flank, the 2/24th attempted an approach from further north, while the 2/23rd was on the left. However, as Brigadier Windeyer observed, ‘in this country an advance of ten yards is the equivalent of 200 yards in open country.’28 The tanks, moving in single file, advanced in groups of three, each tank protected by an infantry section. Two infantry companies attacked with the tanks. Along the road, the Japanese used anti-tank ditches, mines and guns to try and stop the advance. When Gavin Long had a look at a knocked-out Japanese 37-mm anti-tank gun, he noticed two indentations on its shield from tank rounds. ‘It was a two-pounder HE,’ a skinny youth told him. ‘They knocked the crew about—look at that bush.’ Hanging from a branch of the blasted bush behind the gun were the remnants of a khaki uniform. Tom Derrick saw the same gun, with ‘the crew a mangled bloody heap near it.’29

On 20 November, as the battle along the Sattelberg Road continued, Derrick observed, ‘Fighting was hard and bitter with casualties mounting up.’ That day the 2/48th lost one of its finest when Sergeant Bob ‘Snow’ Ranford was shot by a sniper. ‘The end of a dashing, courageous and fearless soldier,’ Derrick wrote; ‘easily the [battalion’s] best.’ The twenty-six-year-old Ranford had been decorated for saving two people from drowning in Australia, then received the Distinguished Conduct Medal for helping save the lives of fellow soldiers at El Alamein, before giving his own life in New Guinea. Next day, Derrick was given command of 11 Platoon, which had lost its commander and platoon sergeant in the earlier fighting. He considered the remaining twenty-two men ‘a very capable crew.’30

On 23 November, it was found that the Sattelberg Road was blocked by a landslide. In any case, it was proving too rough for tanks. Early the next day, Captain Dean Hill’s company was sent across the deep ravine of Siki Creek, ‘a sheer drop of white cliff,’ according to Derrick, to attack Sattelberg via its precipitous eastern slopes. The rugged terrain meant that the only possible approach to the Lutheran mission was through an open kunai patch directly beneath the top of the cliffs. For two hours in the late afternoon, two platoons vainly tried to clamber forward in the face of fierce machinegun fire and a shower of grenades from above. Hill observed of the Japanese defenders that ‘if they ran out of grenades they could use rocks.’31

Derrick’s platoon was then sent in on the right flank. ‘First look at the ground made the task a suicide one,’ he wrote. ‘Jap bunkers on top could fire down on us and drop grenades down, a very sticky [position] indeed. Decided to give it a go, using 4 & 5 [sections]. The move off required great courage and nerve and not a single man hesitated.’32 The dense jungle and steep slope allowed only one section to go forward at a time, each man pulling up the next in line, who was practically beneath his boots. Worming his way to within 15 metres of the enemy positions, Derrick scrutinised the approaches but could see no way forward. He sent a runner back to the signallers to inform Hill by phone. When the runner returned, it was with orders to withdraw.33

In the interim, two of Derrick’s men, Stan Davies with a Bren gun and Don Spencer using a captured LMG, had been able to clear one enemy bunker. Now they were up for more. ‘Things seem to be coming our way,’ Derrick wrote. He got on the phone and told Hill: ‘I think we can get forward, we’ve done over about five posts.’ Hill told Derrick the orders were to break off and try a different approach the next day. But Derrick was adamant. ‘Bugger the CO,’ he said. ‘Just give me twenty more minutes and we’ll have this place. Tell him I’m pinned down and can’t get out.’ Hill gave him the twenty minutes.34

So Tom Derrick had his moment, and his platoon’s action unhinged the Japanese position. Though posts higher up on Sattelberg remained intact, the Japanese abandoned their positions that night. Heavy fire passed over the heads of Derrick’s men for half an hour, and they expected a counterattack to follow, but the fire was only masking the withdrawal.

Derrick’s move had only been the final straw. Four days earlier, on 20 November, the main Japanese supply line from Gusika on the coast to Sattelberg had been cut at Pabu Hill. Troops from Major Keith ‘Bill’ Mollard’s 2/32nd Battalion, led in by local guides, occupied the dominant position and held it for seven gruelling days against determined enemy counterattacks. Pabu Hill became ‘an Australian island in a Japanese sea.’35 Cut off from outside aid, Medical Officer Major Kiernan ‘Skipper’ Dorney did all he could to keep the wounded alive. Those who succumbed were buried in a little cemetery with each name beaten into the bottom of a ration tin and nailed to a cross set above the grave. The battalion padre, Don Williamson, buried twenty-two in all.36 The staunch defence of Pabu Hill made it impossible for the Japanese to hang onto Sattelberg. The famished defenders had run out of food and medicine, and their stocks of ammunition were desperately low. One of them wrote, ‘If I could have one good meal of rice I would gladly die.’37

Patrols on the morning of 25 November found Sattelberg deserted, and Tom Derrick was given the honour of raising the Australian flag from a shattered tree. A mate of his, Max Thomas, went over the route Derrick had blazed up the ridge and observed, ‘Hell, you’ll get another gong for this, Diver.’ Derrick replied, ‘I might catch up with Tex now.’38 Sergeant Jack ‘Tex’ Weston had been awarded both the Distinguished Conduct Medal and the Military Medal. For his courage and gallant leadership, Derrick was awarded the Victoria Cross.

On 15 November, Pilot Officer Robert Stewart was returning from directing artillery fire over the front lines in his RAAF Boomerang. Like the Wirraway, the Boomerang had proved to be unsuitable as a first-line fighter aircraft, but it was ideal for support operations. Gavin Long noted a typical radio conversation between a gunnery officer and a pilot. ‘Is there a MG post at . . .?’ said the gunner. ‘I’ll have a look at the bastard,’ was the pilot’s obliging response. After shelling the post, the pilot reported, ‘I can see pots and pans flying all over the place.’39

Stewart spotted another aircraft up ahead, and was relieved to see the familiar outlines of an American P-38 Lightning. If there were any Japanese aircraft about, Stewart knew the Lightning could outmatch them. If he had known who the Lightning’s pilot was, he would have felt even more secure. Major Gerald Johnson was already an air ace, and by the end of the war he would have shot down twenty-two enemy planes. Unfortunately, he mistook Stewart’s single radial-engine plane for a Japanese example, and opened fire in a head-on pass, not realising his error until he zoomed by. But the damage had been done, and a considerably shaken Stewart had to crash-land the Boomerang at Finschhafen, where it burned out. That error wasn’t the dumbest thing Johnson did: he later had an Australian flag painted on his fuselage among the Japanese ones tallying his ‘kills.’

Despite the loss of Sattelberg, the Japanese still held dominant hill positions at Wareo and further north. Difficult fighting continued throughout 1943 as the Australians moved north and then west along the coast of the Huon Peninsula. The Japanese remnants retreated before them, leaving rearguards to delay the Australian advance. On 22 December, Surgeon-Lieutenant Tetsuo Watanabe, who had arrived by submarine only two weeks earlier, left Sio with 200 men behind the naval ensign of Captain Ken Ukai’s 82nd Naval Garrison. Seven days later, 180 of the men reached Gali 2, where they set up camp, eating green papayas and tree roots to survive.40

New Year for Masamichi Kitamoto was no occasion for joy. ‘Leading the lives of moles in the jungles, we welcomed the year 1944,’ he wrote. ‘One rice cake and some sake was divided among the troops . . . suddenly, there was a roar of airplanes and cracking of machine guns as the enemy planes strafed the camp . . . The rarely held New Year’s drinking party was over . . . I looked toward the sea. About fifty ships with white waves in their wakes were sailing towards the west.’41

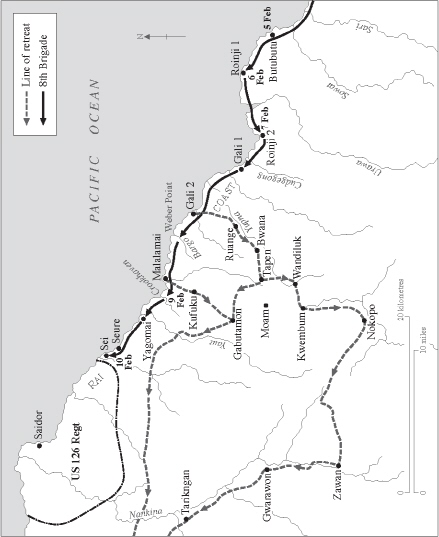

The American 126th Regiment landed unopposed at Saidor on 2 January, the regiment’s first operation since the travails of Buna. The sight of the invasion convoy and the effect of the naval barrage had caused the few Japanese rear-area troops in the vicinity to flee in haste. The tenuous supply line linking them to the Japanese forces further east was now broken. Kitamoto was sent to report on the landing. After dodging air patrols and crossing dangerous river estuaries, his scouting party reached the American perimeter two days later. By then, American engineers were already at work on a new airfield. Back at Kiari, Kitamoto reported his findings to General Adachi, who swiftly cut short his inspection tour and took a submarine out on 5 January, leaving 13,000 of his men stranded east of Saidor.42

Captain Lloyd Pursehouse, whose knowledge of the Huon Peninsula coast had made him such an effective Coastwatcher, had been attached to the 9th Division for the push up the coast from Finschhafen. Pursehouse guided the forward troops, bringing them as far as Sio Mission. There he made a detour across the narrow channel to Sio village and recruited native labourers to help maintain the advance. Returning across the channel by canoe, Pursehouse was gunned down by a solitary Japanese soldier hidden in the nearby jungle.43 There was no safe refuge on hell’s battlefield.

Further west, at Gali 1, the Japanese Army was dying. As the soldiers grew weaker, the death toll steadily rose. On 17 January, Tetsuo Watanabe informed his commander that his unit was starving to death. Two days later, more troops arrived from Sio, further stretching the meagre supplies. On the morning of 23 January, Watanabe went to the field hospital, where the helpless patients looked to him for succour; he could only offer death. As the adjutant issued new blankets, a weeping Watanabe carried out his commander’s orders, placing a grenade beside each man’s pillow.44

Now supplied only by irregular submarine runs and enduring regular aerial and naval bombardment, the Japanese were nearing the end. Those who could walk began the daunting trek to Madang, performing the ‘side crawl of the crab.’ With any westward movement along the coast now blocked at Saidor, the withdrawal had to be along the rugged trails of the eastern Finisterre Range, the end of the earth for many. On 18 January, Kitamoto’s engineers led the way back into the mountains, and the remnants of the 51st Division followed, though without rations. They in turn were followed by the first units from the 20th Division, which had obtained a week’s rations from a submarine supply run to Kiari.45

Having reached Gali 2, the first of 5000 Army troops began the trek into the mountains on 22 January, followed by the naval units the next day and another 1500 troops on 24 January. Other disparate groups followed. Colonel Sadahiko Miyake’s 80th Regiment travelled in three echelons. Only I/80th and II/80th Battalions were provided with rice and salt at Gali 2, as Miyake thought the III/80th, going first, could live off the land. Colonel Kaneki Hayashida’s 79th Regiment, divided into four sections, made up the final organised group.46

Tetsuo Watanabe had set off with the naval units, along with his friend Seaman Okada, who was struggling with malaria. Back home in Tokyo, Okada had a sushi bar in the Shinjuku district, and he had said Watanabe must come and visit one day. Watanabe now watched as Okada collapsed and ‘his face turned pale and bloodless.’ Then blood flowed from his mouth; he had bitten off his tongue so he would die and relieve the burden on his comrades. He was nineteen.47

On the second day, the track climbed up into the mountains. ‘By the track dead bodies were scattered, reeking a horrible putrid smell,’ Watanabe wrote. ‘Those who had perished on this climb must have exhausted their last strength.’48 This route would become known as the Dead Man’s Trail. The ABC war correspondent Fred Simpson wrote: ‘Most of the Japanese soldiery had been left to die of starvation and disease. They were across the track, they were along the track, they were everywhere . . . of food there was no trace.’49 Watanabe had precious little food, but he gave some to a despairing soldier, whose ‘hollowed eyes showed surprise, twinkled a second and misted with tears.’ The chief medic turned to Watanabe and said, ‘If you sympathise with every soldier you won’t survive.’ The gardens near mountain villages provided some sustenance in the form of taro, sweet potato and sugar cane. Nonetheless, after three days one-third of Watanabe’s unit had dropped out. Watanabe nearly joined them. As he slid down a muddy slope in the rain, he felt a wonderful ease coming over him, the beguiling embrace of death. But a fellow soldier saved him, urging him on.50

‘After inching our way over the rocks for a whole day we would cross one peak,’ Kitamoto wrote. ‘The next day, it was another precipice that we had to cling to. When this continued for days, men began to slip with fatigue from the cliffs to their death.’ Major General Kane Yoshihara later recalled that when the men ‘trod the frost of [Nokopo] Peak they were overwhelmed by cold and hunger. At times they had to make ropes out of vines and rattan and adopt rock-climbing methods; or they crawled and slipped on the steep slopes; or on the waterless mountain roads they cut moss in their potatoes and steamed them. In this manner, for three months, looking down at the enemy beneath their feet, they continued their move.’ When men began to freeze to death crossing the 3000-metre Mount Nokopo, Kitamoto took his group over a less elevated route, closer to Saidor—a course made possible by the failure of the Americans to go beyond their perimeter. But other hazards awaited, including flash flooding in the narrow ravines. As he had done in the Saruwaged, Kitamoto went back into the mountains to help the stragglers out. There he met a medic named Sugimoto, a faithful soul who had made the first and second crossings of the Saruwaged, to and from Lae, with him. A former office worker from Osaka city, Sugimoto had shown great skill in dealing with the New Guinea natives. Now, near death, Sugimoto told Kitamoto to leave him. When Kitamoto refused, Sugimoto decided the issue: with a single rifle shot, he took his own life.51

The mountain cold was also a killer. Naked bodies lined the track, stripped where they fell by soldiers desperate for extra clothing. On 6 February, Watanabe met men from Major General Masutaro Nakai’s 78th Regiment, who had come from the opposite direction to help them. Three days later, Watanabe saw the sea west of Saidor. The next day he and the other survivors descended to the coastal track and proceeded to Mindiri on the coast, crossing a series of river mouths under the gaze of waiting crocodiles. The coastal route was easier, but it was still another five days before Watanabe could catch a boat ride to Madang.52

According to Kitamoto, of the 13,000 who had begun the trek, about 9500 starving and exhausted men made it through to Madang, which was little more than a patchwork of bomb craters. The Australian estimate was 8000. It was with good reason that Yoshihara called Kitamoto ‘the mountain god of the Finisterres.’53

Some 16 kilometres inland from Gali 2 was Tapen, the junction of two Japanese withdrawal routes from the coast. Watanabe had passed through here on 26 January. Nearby, the trail towards Saidor crossed an imposing chasm via a suspension bridge. Once the main force had passed over it, on about 10 February, the bridge was cut, leaving thousands of stragglers behind. Masatsugu Ogawa was one of them, part of the force that had been retreating from Finschhafen for the past two months. He arrived the day after the bridge plunged into the chasm. Now he faced a month-long detour via the higher mountain route through Nokopo.54

Captain Frank Farmer’s company from the 35th Battalion moved up the Dead Man’s Trail from Gali 2 on 14 February. Ahead of them went Papuan scouts, including Corporal Bengari, who had infiltrated Japanese-held villages to gather intelligence during the Salamaua campaign. Farmer’s infantrymen hauled each other up the steep muddy slopes into the ranges, taking rest breaks beside the decomposing bodies of Japanese troops. One Japanese naval rating was found alive, semi-conscious and suffering from malaria and malnutrition.55 The Australians struggled on to Ruange village, perched high on a razorback ridge. Farmer’s men counted sixty bodies on the way to Ruange and another five in the village.56

At the next village, Bwana, the Australians met with resistance and killed twenty-seven Japanese. The PIB scouts found another thirty-seven bodies in the village and killed five more heading up the track. On 17 February, they reached Tapen, a large village of about fifty huts spread out on a plateau astride the track and surrounded by hundreds of garden plots. A reconnaissance found about 100 enemy troops in occupation, so Farmer deployed his men for an attack. Those with automatic weapons would advance line abreast, while the clever Papuan scouts would get around the flanks, clearing out the gardens and cutting off any escapees. ‘They were ruthless fellows,’ Lieutenant Dick Youden said of the scouts. ‘They could smell the Japs.’57

The Australians attacked in the late afternoon, catching the enemy unawares with a wall of automatic fire; fifty-two Japanese were killed within 50 minutes. The Papuans killed fifty-one more in the gardens and along the tracks to Wandiluk and Moam. Bengari and two other Papuans accounted for forty-three of them. Farmer’s men were greatly helped by the exhaustion of the enemy soldiers, who had posted no forward sentries and had left extensive defence works unoccupied. Sergeant Tom Griffith was the only Australian wounded, nicked across the scalp by a sniper’s round. An angry Griffith cut down the sniper with his Owen gun before his grenades accounted for four other Japanese hiding in the same hut. As in the other villages, more corpses were found, in this case another forty. The PIB war diary commented: ‘decaying and filth everywhere.’ On 20 February, the village was burned to the ground.58

Wandiluk was next. Though only 8 kilometres from Tapen, it was near the bottom of the Yupna Gorge, down a winding, precipitously steep track. Farmer would send only forty-three men into the gorge, stripped down to their basic equipment and accompanied by the PIB scouts. New Guinea had few landscapes more daunting than this. The soldiers picked their way down the tenuous, muddy track, clinging to vines and roots. On the way, they had to negotiate the even steeper banks of four streams that cut across the track, forcing them to remove the basic pouches from the front of their uniforms to squeeze along the cliff-side track. They passed some eighty Japanese corpses; the stench of death was everywhere. Down below, they could see planes strafing the village, keeping the Japanese distracted. After a gruelling five-hour descent, the Australians attacked at 1700, encountering sparse resistance and killing forty defenders. The PIB scouts accounted for another ten. Just past the village lay a kilometre-deep drop into the lower part of the Yupna Gorge. Seven fleeing enemy soldiers crashed to their deaths on the rocks at its base.59

This was no place to be wounded. One Australian soldier who had been hit in the legs by a grenade blast had to be carried back to the coast. In a superhuman effort, the native bearers somehow got him back up out of the gorge on their shoulders. The audacious Bengari was also hit, shot through both shoulders as he fired from atop a native hut, yet somehow he was able to walk out. The men advanced further up the gorge after building a tall ladder to help scale a 60-metre-high cliff, but once past Kwembum—and another seventy-four Japanese bodies—the Australians were finally beaten by the terrain. However, some of the PIB scouts managed to get through to Nokopo and set the village afire.60

Warrant Officer Alf Robinson, who was serving with the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit, was asked to assess the feasibility of operating a supply line between Tapen and Wandiluk. This was the same Alf Robinson who two years earlier, as a NGVR rifleman, had escaped from the Japanese massacre at Tol. He had operated over some of the most difficult country in New Guinea, but now he reported, ‘I can confidently state there is no feature anywhere approximating the difficulties of the proposed L of C.’61 Captain Ernest Hitchcock, the PIB commander, who had spent twenty-three years in New Guinea, said the terrain was ‘not fit for any white man.’62

Another patrol came up from the coast at Malalamai. It reached Gabutamon on 18 February, killing forty Japanese and finding the same number already dead. The patrol then set out to reach Tapen from the west, traversing the steep razorback ridges. It was more like a mountaineering expedition, with the lead man digging finger and toe holds into the treacherous slopes for those who followed. In some places the men had to be roped together, and at one boggy defile they were up to their shoulders in mud, travelling less than a kilometre in eight hours. Muddy patches in the kunai at the edges of cliffs indicated where enemy soldiers had fallen to their deaths. At the bottom of a 100-metre-deep chasm—probably the one that had stymied Masatsugu Ogawa—the Australians found ropes dangling from the cliff edge high above. Beneath the ropes’ lower ends lay some eighty decomposing bodies, smashed across the rocks. The Japanese soldiers who had reached this point had not had the energy to climb out. Some had tried, but others had just lain down to die.63

The terrain was hellish, but Tapen and Wandiluk held something worse. The first signs came on the trail up into the ranges: corpses with chunks of flesh cut from the buttocks. In the villages, the ghastly sights were repeated. Clearly, an expert butcher had been involved, ‘so cleanly had the muscles of arms and legs, the buttocks and flesh around the ribs, and even the cheeks of the face been removed,’ Lieutenant Gordon Holland wrote. In one hut in Tapen, Lieutenants Geoff Rennie and Dick Youden—both from the 30th Battalion and attached to Farmer’s unit—found a heart and liver still dripping blood and wrapped in banana leaves. A large hut on stilts in the centre of the village was like a slaughterhouse. Two bodies on the bamboo floor had been gutted. One had slices of flesh missing from the buttocks; the other had been stripped to the bones. Outside, dixies and clay pots held human flesh ready to be cooked. In another hut, flesh was already roasting over a fire. Youden observed, ‘We all grew up pretty quickly.’64

At Wandiluk, Farmer and Captain Robert Escott saw more signs of cannibalism. On one body, ‘all the flesh had been removed and all that remained was the framework of bones.’ In one hut a pile of flesh had been prepared for cooking, and in another, there was flesh in a dixie and a human liver cooking over a fire. Elsewhere, Escott found a fresh corpse with deep cuts down the backs of the legs. ‘The look of horror on [the dead man’s] face was so terrible that I am convinced they started to carve him up before he was dead,’ he said. Farmer had all his men witness these scenes before burning the village to the ground.65 For the young Australian soldiers, the ghoulish scenes they had witnessed could not be so easily erased.