19

‘Some bastard is going to

pay for this’

Shaggy Ridge

December 1943 to February 1944

Like a fallen prehistoric beast, Shaggy Ridge lay across the Finisterre Range above the Ramu Valley, pointing the way north to the coast below Madang. A thick green hide of dense jungle covered its western flank, while on the open, eastern side veins of jungle stood out from the crevices where streams bled from its side. At the top, it was as if the hide had fallen away, leaving the fossilised vertebrae standing out in sharp relief along the narrow crest of the ridge. There was no battlefield more challenging.

On 15 December, Major General Vasey had visited Shaggy Ridge, seeing for himself the single weapon pit atop the narrow razorback that represented the front line. ‘G’day,’ he said to Frank Murphy and Bill Ryan, and offered them a smoke.1 Later, Major Garth Symington, the acting commander of the 2/16th Battalion, told Vasey that the men were fed up with just patrolling. ‘I think we could take Shaggy Ridge,’ he added. ‘I don’t think you could,’ Vasey replied. ‘Two colonels have told me it is not possible to take it from the front.’ But Symington held his ground. ‘Thanks, Symington,’ the General said. ‘That’s interesting.’ Some days later, Brigadier Ivan Dougherty phoned Symington. ‘Garth,’ he said, ‘did you tell Vasey you could take Shaggy Ridge?’ ‘Yes, I did,’ replied Symington. An obviously annoyed Dougherty then told him, ‘You had no right to do it, now you have to do it.’2

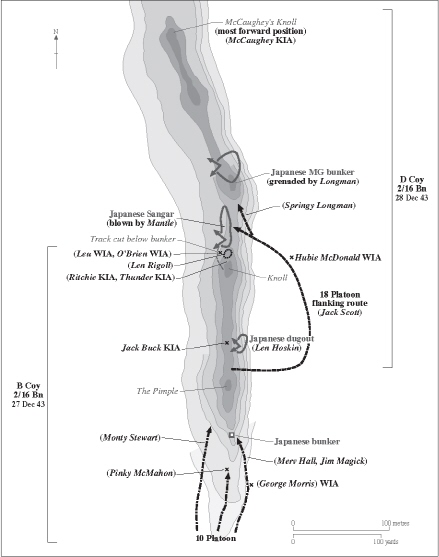

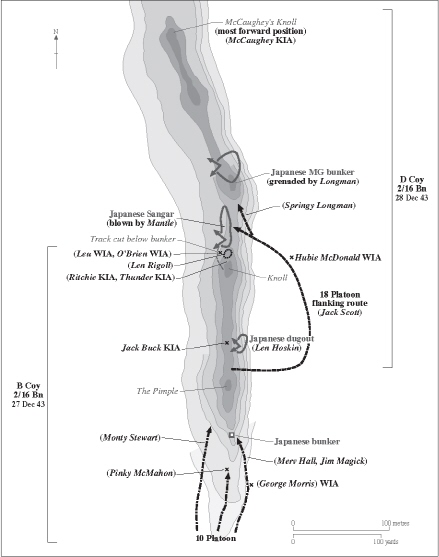

Sergeant Tom ‘Pinky’ McMahon, who had fought with distinction at Gona, would plan and lead the critical initial assault on the Pimple, the forward-most Japanese position on Shaggy Ridge. ‘You know what you’re doing,’ his platoon commander told the redhead. ‘I’ll go along with you.’3 With reinforced bunkers echeloned back along the crest, most shielded from direct fire by the Australian artillery, the Pimple seemed impregnable. Heavy air and ground support were laid on for the attack, including the most intense artillery bombardment of the New Guinea campaign thus far. On the morning of 27 December, every eye was turned to the Pimple to watch the awesome display of firepower. From up on the 5500 Feature west of Shaggy Ridge (and named for its elevation in feet), Lieutenant Lance Logan phoned back, ‘Boy, are they pasting shit out of Shaggy.’4

As if in a castle siege, the assault troops placed two bamboo ladders against the rock face below the Pimple, but the loose rock provided no firm footing: the men would have to scramble up as best they could. With adrenaline coursing through him and knowing time was at a premium, McMahon threw himself at the wall of rock and somehow managed to make progress up its crumbling face. Behind him, Merv Hall’s section began angling around the right side in an attempt to gain better purchase.

McMahon levered himself over the crest and scrambled into a dip in front of the Pimple as the first shots cracked overhead. He fired back with his Owen gun and then threw a grenade into the enemy bunker. It was immediately thrown back, landing by his side to be quickly brushed away down the slope. McMahon delayed his next grenade throws, but they too came back. One exploded near his left side, shattering his hand and wounding his head. Blood coursed down his forehead and into his eyes. By now, he had thrown his six grenades and was rapidly using up his Owen ammo. He suddenly realised he was still the only man up there. ‘Come and give me a hand,’ he shouted to the others. ‘Why don’t you come?’5

Shaggy Ridge: 27–28 December 1943

Warrant Officer George Morris was an imposing man, standing over 2 metres tall. Against Symington’s wishes, he had joined the assault. Symington later said, ‘The thing you could see first was Pinky McMahon’s red head and George Morris, bloody tall, lanky George, crawling their way up there.’6 Morris had edged around to the right side before a burst of fire from an enemy position further down the ridge stopped his progress. He heard McMahon calling for help, and then a grenade burst almost on top of him. Morris and three others were wounded, probably by one of the Australian grenades that the Japanese had thrown back at McMahon. Nearby, Merv Hall also scrambled up the slope.7

The bombardment had left the crest bare, but down below the tree line on the left side of the ridge, the shattered wood had piled up to create a tangled platform of sorts. Monty Stewart held his Owen gun with one hand and used the other to navigate through the splintered tree limbs as he led his section forward. Stewart emerged from the debris beside an enemy bunker. As he brought the Owen to bear on a defender crouched in the bunker doorway, he saw movement from the corner of his eye. On the other side of the ridge, a man broke the skyline and charged the bunker: it was Merv Hall. Stewart then watched as the defender flipped back into the bunker under a burst from Hall’s Owen gun. When another defender dashed out, Hall stepped forward and crashed the butt of his empty Owen down on him before tossing grenades through the doorway.8

Stewart then led his men around the Pimple and along the razorback, still moving through the tangled mass on the left side of the ridge. Ahead was a small knoll behind which the ridge top appeared to drop away. As the section reached the knoll, Danny Leu took a machinegun burst across the chest and collapsed back into the tangled scrub. Stewart held onto him as Japanese grenades began landing nearby, brushing them away down the slope before propping up his haversack for cover. As more men arrived, he helped get Leu out.9

Frank Murphy and Bill Ryan took over the forward position just behind the knoll. Later that morning Jack Ritchie, another Bren gunner, came forward to relieve Murphy. Before leaving, Murphy told him, ‘If you want to have a go at it, go around to the left,’ then added, ‘Whatever you do, don’t put your head over the ridge or you’re a goner.’ Murphy had not gone far when a single rifle shot rang out followed by a shout of ‘Bloody hell, no!’ from Tim O’Brien, the No. 2 on the Bren. Ritchie had chanced a look forward and now lay dead in O’Brien’s arms.10

In the late afternoon, Sergeant Eric Thunder, an interpreter attached to 21st Brigade, came up to the front line. He made straight for the knoll, where he was told in no uncertain terms not to raise his head over the top. The men then watched stupefied as Thunder got up on the crest and shouted out in Japanese, apparently trying to elicit the surrender of the position. It was all over in seconds, and Thunder’s body tumbled away down the side of the ridge.11

That night, the men dug a trench around the left side of the troublesome knoll, tough work in the rocky ground. Further forward, Len Rigoll kept the enemy heads down by firing from a slight recess in the ground. He stayed there for sixteen hours straight, enabling the trench to be dug unimpeded.12 By dawn, the trench was alongside the enemy bunker but below the crest of the ridge; the means to blow the bunker was also at hand. The engineers down in the valley had made up blockbuster bombs, each consisting of a metal canister filled with about three kilograms of ammonal and detonated by a grenade screwed to the base. Ray Mantle was up at the front of the trench when one of the bombs was handed to him. ‘Here, you get rid of this,’ he was told. Mantle flung the bomb into the hole at the side of the bunker before ducking back down. A fearful blast blew out the entire side of the bunker, taking Mantle’s hat with it as the shock wave washed over his position.13 The way forward was open.

As the bunker blew, the men of Lieutenant Jack Scott’s platoon were climbing up the eastern side of the ridge, poised to storm the next set of bunkers along the ridge. Having seen the perils of moving along the top the previous day, Scott had decided to attack the defences from below. He was using a walkie-talkie so he could be talked onto the objective by observers up top. Smoke shells would help cover his approach, while supporting fire from the crest would distract the defenders. Scott’s platoon had descended the ridge at dawn, sliding most of the way down the initial descent owing to the steep incline and the loose rubble from the bombardment.14

Charlie Cunningham, the battalion padre, went with the platoon. ‘What do you think you’re doing here, Pard?’ Scott asked him. ‘Wherever my boys are going, I go too,’ Cunningham answered. Once the men had moved a few hundred metres along the side of the ridge, it was time to ascend. Scott spread them out so they would reach the crest in a line abreast, giving them the best chance of striking the enemy at the right point. Hubie McDonald, Bill Broughton and Clarrie Trunk were out on the right flank when someone shouted, ‘Look out, there’s a grenade.’ The three were wounded by the blast; McDonald was blown off the side of the ridge, stopping only when he hit a ledge further down the slope. Cunningham went down and told him, ‘Your family has already lost one son. I am going to see to it that they don’t lose another.’ Hubie had transferred to the 2/16th after his brother Terry lost his life on the Kokoda Trail. Now he lay seriously wounded on another New Guinea mountainside.15

Higher up, Scott was given his last instructions on the walkie-talkie. ‘You’re directly below your objective, you are now on your own,’ his company commander, Captain Vivian Anderson told him. Sheltered under the overhang at the top of the cliff, Scott planned the final assault. It would be led by the platoon sergeant, ‘Jack’ Longman. Known to all as Springy, Longman was a battalion original whose standard comment was a laconic, ‘She’ll be right, mate.’ He was also a livewire, always running about and in the thick of any action. Some looked on him as indestructible: on an earlier patrol down in the valley, he stood up and fired his Owen gun while bullets seemed to pass him by. He was the right man for the job.16

Scott’s plan was for three men to climb the cliff carrying only Owen guns, spare magazines and a few grenades. Longman would lead this group to the right, and Scott would bring the rest up on the left once Longman silenced the bunker. The other men formed a rough pyramid to support the three climbers while they scrambled up far enough to find handholds on the rock face. It was just after midday as ‘Springy’ Longman pulled himself over the crest with his left hand while firing his Owen gun with the right. The bunker, covered by loose rubble thrown up by the bombardment, was dug into the rock right in front of him.17

Longman’s fire was immediately answered by the Japanese. Two of his men were hit, but despite the steep approach and the loose rubble, Long-man managed to crawl up to the bunker as an enemy machine gun fired over his head. Further back, ‘Jock’ Agnew fired his Owen at the bunker aperture to give Longman some cover, while down below, in a well-practised tactic, Jimmy Knight managed to position his Bren gun so it too targeted the embrasure. As Knight’s Bren cut out, Longman pushed a short-fused grenade through the narrow slit. The way ahead was clear.18

Further back, enemy troops in the dugout on the side of the ridge below the Pimple were still causing trouble. Jack Buck had been lying prone on the crest, leaning out to fire downwards into the position, when he was shot straight through the mouth. Grenades lowered on bamboo poles were also ineffective because the position was dug into the side of the ridge in an L shape, allowing the defenders to shelter from the blasts by ducking around the corner into the tunnel.19

Meanwhile, the wounded Hubie McDonald had been dragged up the side of the ridge and placed on a stretcher. Padre Cunningham and ‘Bud’ Harley had begun to carry him back when they heard a shout: ‘Look out, the blockbuster is about to go off!’ There was an almighty blast from below and debris whistled by, one piece striking the padre on the knee.20 The explosion had come from a blockbuster bomb that the engineers had used on the troublesome dugout in the side of the ridge. With two fellows holding his legs, one of the engineers, Len Hoskin, had been lowered down head first to drop the bomb into the small opening at the top of the dugout. His first attempt missed the hole and took some time to explode further down the ridge side. Hoskin then ‘told the fellows to heave me back in a hurry when I shouted out. I pulled the pin, counted to four . . . shouting out at the same time as I let it go. As I came back up I was delighted to see the bomb drop truly into the opening and that was that.’ The two bodies that were recovered were unmarked, killed by the shock wave. After they had been searched, one of the men heaved one body down the side of the ridge.21 There was no love lost between the Japanese and the Kokoda veterans of the 2/16th, whose mates had been used for bayonet practice back on Brigade Hill. A prisoner from another bunker, lying face down further along the ridge, never saw his end coming. ‘Just watch this,’ a Kokoda vet quipped as he walked beside him with the muzzle of his Owen gun pointed downwards. ‘I hate the bastards.’22

With enemy snipers further back along the ridge now seeking targets, Jack Scott had his men move off the crest into the timber cover on the western side. However, it was only a matter of time before the trees attracted shells from the mountain guns. Scott, who had experienced tree bursts at Ioribaiwa Ridge, was quick to lessen the risk. The old heads in the platoon were already hacking at the trees with their bayonets. Scott headed back to get axes just as the expected shells began falling.23

Lieutenant Sam McCaughey had led his men further forward along the ridge. He was accompanied by Johnny Pearson, the artillery observer who had parachuted into Nadzab at the start of the campaign. Pearson’s task was a demanding one. Using the 25-pounders in a sniping role, he called down fire as close as he dared to the Australian positions. To John ‘Blondie’ Bidner, the forward section commander, it was as if you could reach out and catch the shells as they went by.24

The Japanese had dug most of their positions down the ridge’s timbered western flank for better protection from the Australian artillery. McCaughey’s men had to crawl in single file along the crest with their rifles slung across their backs. Bidner had a sugar-bag full of grenades as well as some blockbuster bombs that he would pass forward as required to clear the enemy positions. One man at a time went forward to clear a dugout while the others provided covering fire. Jimmy McCulloch took care of one, then Wally Offer saw to another, and then it was Bidner’s turn—the section was run on very democratic principles. Since Bidner’s target was dug into the side of the ridge, he used a blockbuster. The dugout’s embrasure faced out to the flank, so he edged his way unobserved along the ridge crest, found the small entrance, dropped the charge inside, then leaned back to avoid the fountain of earth that erupted in front of him.25

Now cresting the steep knoll they called Green Sniper’s Pimple, McCulloch took out two more posts over the top with grenades.26 The Japanese defenders, mostly young men wearing three or four shirts to keep out the night cold, died at their posts. McCaughey’s men quickly occupied the enemy pits around the further knoll, the highest position along this part of the ridge, denying the Japanese an extensive view of the Ramu Valley. The mountain guns were now the danger, and McCaughey’s boys didn’t muck about. Lacking axes, they used concentrated Bren and rifle fire on the trunks to cut down the trees.27

When the mist lifted the next morning, the shelling recommenced, more accurate than ever. During the night, the Japanese had moved two 75-mm mountain guns out of the Faria Valley to Kankiryo, and these were now firing directly along the ridge. The steepness of the slope meant that the men on the final knoll were almost beside the tree tops, so even an inaccurate shot to the west could result in shells bursting across the Australian positions. It was not long before the gunfire took its toll. After Wally Offer was hit, Sam McCaughey called out for a stretcher bearer. Then he said, ‘Bugger it, I’ll do it myself,’ and moved out to help Offer. Another blast rolled across the ridge, and McCaughey was caught in the rain of deadly shell fragments. Bidner, who had also been hit, tried to help his platoon commander, but McCaughey just turned to him and said, ‘I’ve had it, Blondie.’28 The son of one of Australia’s most esteemed pastoralists died on the ridge beneath the knoll that would bear his name.

The men of the 2/16th had done what Garth Symington had told General Vasey they could do, throwing the Japanese off the key heights of Shaggy Ridge. Now the shimmering blue sea beckoned from the north.

A flight from RAAF No. 4 Squadron was based at Gusap in the Ramu Valley. Its men had a strange war, spotting enemy positions and directing artillery fire or acting as guides to bring fighter and bomber strikes onto targets on and around Shaggy Ridge. The squadron was equipped with Wirraways and Boomerangs, ideal for loitering about the sharp ridges and deep valleys of the Finisterres.

Two Boomerangs, nicknamed Bluey and Curley, operated daily over the Australian lines. When flying up a jungle-covered valley towards a mountain spine, the challenge for the pilots was to judge the correct incline, often greater than the aircraft’s maximum rate of climb. Judgements had to be sharp, because the option of turning back was rapidly lost as a valley narrowed. ‘There were many times when I thought I had misjudged it and came out with heart pounding,’ Flying Officer Alex Miller-Randle wrote. Flying down the valleys was greatly preferred.29

‘What a way to spend New Year’s Eve,’ thought Allen ‘Ossie’ Osborne as he watched Bluey the Boomerang weave its way across the northern end of Shaggy Ridge. Osborne served with Major Gordon King’s renamed 2/6th Commando Squadron, manning an observation post on the 5500 Feature west of Shaggy Ridge. It was a monotonous task, so Osborne appreciated the flying display.30 From the cockpit of his Boomerang, Flight Lieutenant Eric ‘Bob’ Staley peered down into the thick jungle that spread along the ridge-tops behind Kankiryo Saddle. Staley was looking down for any sign of the enemy. If he caught sight of a mountain gun, he would direct the 25-pounders onto them. Some 300 metres above Staley, Alex Miller-Randle piloted a second Boomerang, keeping an eye out for enemy fighters.

There was an art to flying over the enemy positions. For observing, the best way was to fly along the valleys below the tree line so as to see beneath the jungle canopy. The pilot would then break away low to the left or right to deprive anyone on the ground of a clear shot through the trees.31

After some harsh lessons from the Australian artillery, the Japanese officers had issued orders not to use anti-aircraft guns against the spotter planes for fear of retribution. However, after the reverses on Shaggy Ridge and the loss of a mountain gun to counter-battery fire, the Japanese were determined to hit back in some way. So, as Staley’s Boomerang circled with perceived impunity, Sergeant Major Fujita had no intention of leaving him unmolested. Five of his men were waiting for the aircraft to appear overhead, and as Staley brought his plane down low, they opened fire.32 The Boomerang was a sturdy aircraft, and the pilots had often brought them home full of bullet holes, but not this time. Flying at tree-top height, Staley’s Boomerang immediately crashed into the jungle.

Allen Osborne had seen the plane descend to the tree tops. Now he stared at the spot on the ridge where it should reappear. Not having a compass or a map, he scraped a line in the dirt with his boot, pointing to the spot where the Boomerang had vanished. Then a small stream of smoke rose from the jungle, clearly marking the location of the fallen bird. The sound of exploding ammunition echoed back from the ridge.33 In the sky above, Miller-Randle had also lost sight of Staley and was vainly trying to raise him on the radio. ‘Panther One. Do you read me? Over.’ Then he also saw the plume of smoke rising from the jungle-covered hillside.34

When an Australian patrol reached the crash site the next day, it was found that fire had burned half of one wing and the engine; the plane was otherwise intact. Bob Staley had been killed in the crash and was lying next to the wreck. An engraved holster hung from his body, the gun taken. The Australians cut the parachute from Staley’s broken body and scraped a shallow grave for the fallen flyer.35

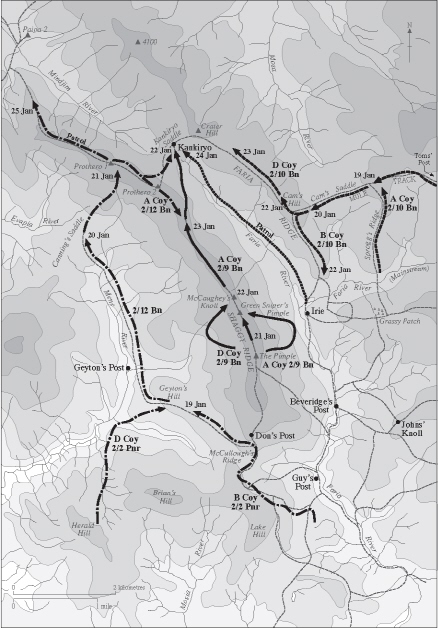

The new year of 1944 brought a new brigade to Shaggy Ridge, Brigadier Fred Chilton’s 18th, replacing Dougherty’s 21st Brigade. Chilton’s task was to capture the remainder of Shaggy Ridge and drive the Japanese back to Madang. Operation Cutthroat would be the first operation for the rebuilt brigade since it had won the battles of Buna and Sanananda. The 2/9th’s Bruce Martin put the challenge of fighting on Shaggy Ridge into perspective: ‘The Cape and Sanananda were nightmares to fight in, but the steep, slippery, long zigzag climb, steaming and wet was terrible. We used to piss ourselves with effort carrying supplies in.’36 East of Shaggy Ridge, the 2/10th Battalion launched the operation along Faria Ridge on 20 January, and the next day the 2/9th went in along the top of Shaggy Ridge.

Shaggy Ridge area: 19–24 January 1944

When morning came, the ridge was shrouded in mist and there was a tense wait for the cloak to lift. After air attacks, the men of the 2/9th moved along the crest but soon encountered a machinegun position tunnelled into the side of the ridge. When a Japanese soldier sprang from his weapon pit and tangled with Tom ‘Ginger’ Childs, the machine gun sent both men to their deaths, locked together in a wrestling match.37 It was only when Eric Knight got close enough to grenade the position that the platoon was able to advance towards the eastern side of Green Sniper’s Pimple. This feature, captured earlier during the 2/16th attack, had been given up owing to the mountain-gun menace. The Japanese, well dug in on the western side behind the protective lee of the ridge crest, hurled grenades over the top, while their snipers waited to pounce on anyone who dared show his head. As with the earlier attack by the 2/16th, success would come from below.

Doug Wade fired his Bren gun from further down the slope as the rest of his platoon scaled the ridge. Clutching tufts of short kunai grass that grew amid the rubble, the men hauled themselves up the battered slope, dodging grenades rolled down from above. Ron McAuley copped a buttocks-peppering blast, but he kept going up the ever steeper gradient.38 Shawn O’Leary later wrote: ‘Guns break into red laughter and slugs churn around you. You’ve got to climb; climb where there are no holds and the slopes fall down like a leaning wall . . . Your chest burns with the pain of effort and you fight for gulps of air . . . Thirty feet from the top you lie, and the grenades commence to rain as the Japs, from the shelter of the lip of the hill, hurl them at you. The mountain-guns open a barrage against which Brens can do nothing. This is hell . . . You must lie . . . and lie and wait . . . and wait. Wait for the caress of agony from flying steel . . . There never was country such as this.’39

As Ron McAuley approached the peak of Green Sniper’s Pimple, he could see that the defenders, well ensconced with a ready supply of grenades, were winning the fight. Most of the Australians only carried two grenades, so McAuley headed back down the side of the ridge for more. By the time he returned, things appeared to have cooled down, but when he started throwing more grenades, more came back. When one landed in his trench, McAuley jumped out, only for a second grenade to land beside him. Instinctively, he tumbled back into the trench just as the first grenade exploded, badly wounding him in the head. His first and last action of the war was over.40

The fight for control of Green Sniper’s Pimple continued. Once Doug Wade reached the crest, he fired his Bren down into a gully at Japanese positions that were dug in along the slope with empty rice sacks veiling the entrances. The targets were difficult to see, so Wade stood up to get a better shot, feeling the reassuring recoil of the Bren as he sent forth a burst of fire. ‘God, be careful,’ cried Gordon Davidson, his mate from the Riverina. He heard the single crack of a rifle-shot, and the valiant Wade fell back into Davidson’s arms. When Jim Pacey chanced a look, two more shots rang out, the first striking the side buckle of his helmet and pushing it up over his head, the second going straight through the raised helmet.41 The Australians held Green Sniper’s Pimple, but they would not be going any further for the moment. The decisive move would come in the north.

At the head of the Mene River valley, on the western side of Shaggy Ridge, Lieutenant Colonel Charlie Bourne’s 2/12th Battalion prepared to attack the northern end of the ridge. Here the ridge levelled out at a feature named Prothero by a patrol from the Papuan Infantry Battalion after Ron Protheroe, who had drowned in the Watut River in July. The north end was known as Prothero 1 and the south, Prothero 2. Like clockwork, the rain started in the late afternoon of 21 January and continued through the night. Without shelter or fires, the men huddled together as best as they could with their gas capes drawn around them, their thoughts on the coming battle. Tojo Etchells, back with the battalion after being wounded at Buna, later remembered how ‘it poured all night and the bloody water came down like a bloody waterfall.’42 It would not be an early start next morning, as the plan for Operation Cutthroat relied heavily on the 2/9th and the 2/10th drawing the Japanese defenders onto them up on Shaggy and Faria Ridge respectively.

The climb up the near-vertical river bank was an early test. The first men crossed the start line just before 0930 as the 2/9th attack along the top of the ridge began. With strict instructions to maintain silence as long as possible, the men of Lieutenant Alwyn Francis’ platoon made their way carefully up the spur out of the valley. The men travelled light, ditching their helmets for slouch hats. As they climbed, they could hear the Japanese mountain gun firing at the men of the 2/9th further along the ridge. Where the spur narrowed, two trees bracketed the track, a land mine squarely between them. With no defenders in sight, the men edged between the left-hand tree and the mine. Later, more explosives were found buried beneath it.43 The defenders, distracted by the other attacks, had been caught unaware. According to Captain Masahiko Ohata, there was only one infantry squad defending the approaches to Prothero; in hindsight he would ask himself, ‘Why [didn’t] I demand [the] battalion to reinforce in the valley below Prothero.’44

Francis’ men reached the crest and took up defensive positions as the rest of the battalion gathered. There was a deafening crash of artillery, and Francis looked back to see shell fragments raining death onto the gathering infantrymen. The losses from those opening salvoes were horrendous. Despite going to ground, Bob Davis found no protection from the shell bursts: one fragment passed through his hat and another struck his leg. Scrambling for cover, he passed the big redhead ‘Bluey’ Rowe propped up against the side of a tree, apparently hit by machinegun fire across his midriff and vainly trying to hold onto life. Nearby, Brian McNab glanced across to his left to see, just yards away, ‘Homey’ Connell lying dead from a fearsome blow to his head. Also down was ‘Pop’ Alcorn: a shell fragment had taken his arm off before a blow to the head had killed him.45

McNab’s section commander, Gordon Marsh, was close by and was one of the first to appreciate what was happening. Ted Crawford saw Marsh pointing down off the side of the ridge. ‘There’s the bastards,’ Marsh shouted as he headed off. McNab followed as another great blast rang out. As he hurtled across the slope he passed a body, the head so smashed up it was almost unrecognisable. It was Marsh. More than half of McNab’s platoon would be killed or wounded that day.46

‘Bluey’ Berwick was quick to dive for cover behind a log when the shelling started. Following another blast, he felt his legs go numb and looked down to see blood. Then the pain hit. Teddy Edwards took one look and called for the stretcher bearers, who gave Berwick some morphine. He was carried off the ridge that night minus his right leg.47

The wiry stretcher-bearer ‘Tex’ Parnell walked towards the medical officer, Captain Jim McDonald, holding one of his arms with the other. McDonald could see daylight showing through the shattered arm, which had been torn open from shoulder to elbow and was attached by only two shreds of tendon. Max Thow had seen a mate killed next to him at Tobruk, but that sight of Parnell became his enduring image of the war. McDonald too was dumbstruck. It was Parnell who spoke first: ‘Hey, Doc, look what I have done to my arm! Can you do anything for it?’ he said. ‘I’m afraid it’s got to come off, Tex,’ McDonald replied. Parnell sat down on a log. ‘OK, Doc,’ he said. ‘Whip it off.’ Next day Parnell made his own way down the ridge, but the exertion would kill him. The inspiration of his stoic courage would live on.48

Lieutenant Brodie Greenup was in command of the signals platoon. When the shell fire began, Greenup was with Colonel Bourne, moving up the track towards the ridge. ‘What do you make of that?’ Bourne asked him. ‘Sounds like a demolition to me,’ Greenup replied. Bourne then said, ‘Hold the track and we’ll go around into dead ground.’49 Though there was dead ground from direct gunfire, there was no such thing from the tree bursts. Bourne could only watch as men fell all around him. He called over the artillery officer, Captain Bill ‘Bluey’ Whyte, to organise counter-battery fire, but before Whyte could reach him, Bourne himself was struck down.50 Captain Norm Sherwin, the adjutant, watched as his CO suddenly fell and rolled over, grabbing at his abdomen and crying out, ‘I’m wounded, I’m hit.’ Sherwin propped him up against a tree and looked for the wound. He could see only a narrow red slit with a seemingly innocuous shard of metal poking out from it. There appeared to be no bleeding. ‘You’re all right, Charlie,’ he told his commander. ‘It’s only a little bit of shrapnel.’ Sherwin grabbed the metal between finger and thumb and pulled on it. In fact, it was more than 15 centimetres long and very jagged. Bourne passed out but survived. The medical officer later asked Sherwin, ‘Are you the bloody idiot who pulled it out?’51

The Australians had identified their nemesis: a Japanese mountain gun sited across the gully from the main track. Firing out the back door of its bunker at murderously close range, it sent shells smashing directly into the thick belt of jungle on the ridge line and raining deadly fragments upon the Australians. Inside the bunker, nine Japanese gunners from the Kageyama Mountain Artillery were firing the deadly high explosive shells as rapidly as possible. The gun commander, Second Lieutenant Yo Baba, a twenty-seven-year-old from northern Kyushu, was in charge of the most potent Japanese weapon on Shaggy Ridge, a 75-mm Type 94 mountain gun.52 The position Baba and his men occupied was a recent construction. The earlier 2/16th Battalion attacks along the ridge had underscored the need to shell both sides of the ridge. The bend in the ridge just north of the Pimple meant that a gun placed on the northernmost end could fire back along the western side.53

Six men had started construction of the gun bunker, at Prothero 1, on New Year’s Day. They climbed up the ridge from Kankiryo before dawn and worked until dusk, first digging the base a metre deep and then constructing the bunker. They laid a floor of wooden planks and reinforced the outside of the bunker using heavy logs; the embrasure faced south, along the western flank of Shaggy Ridge. They even made a back door, with an observation window alongside. The roof was covered with about two metres of earth and saplings planted for camouflage. The position was completed on the third day. On the next, 4 January, all available personnel carried the gun parts up the steep and muddy track and reassembled the gun inside the bunker; the ammunition was hauled up in the afternoon. On 5 January, Baba’s men took up their personal belongings and an extra supply of shells and set up their tents under the jungle canopy around the new gun emplacement. On 8 and 9 January, after the gun was fired for the first time, the Australians shelled the area heavily and bombing raids followed. Ten days later, more shells were carried up and after some were fired, the area was again heavily bombed. Each time, the bunker’s sturdy construction and ingenious location protected it from these attacks. It had been built behind Shaggy Ridge, in defilade from the Australian artillery fire and at the edge of the Prothero plateau making it a difficult bombing target.54

When the 2/9th Battalion had begun its attack on the morning of 22 January, Baba’s gun had fired thirty rounds at 0830 and then more as the attack developed. It was about 1230 when a soldier dashed up to the rear door of the bunker with the incredible news that the Australians were almost on top of the ridge. Baba immediately ceased firing and positioned two LMG teams to support a small machinegun bunker that was already manned.55 Baba’s main concern was that his gun still faced south, but by detaching the gun trail, his men were able to turn the gun so it fired out the back door, though with limited traverse. The other difficulty was the lowness of the floor. With its base just a metre below the bottom of the doorway, the gun could be fired only while elevated, with the shells fused to explode on contact with the trees. By 1330 it was obvious to Baba that it was no mere patrol on the ridge: the Australians were arriving in force. He waited as more of them gathered in the kill zone beneath the trees. Then one man shouted and pointed towards his position, and Baba immediately opened fire. Knowing their fate was sealed, the Japanese gunners worked like demons, firing at least twelve rounds a minute. Each of those minutes could well be their last.

Bourne’s 2IC, Major Colin ‘Bull’ Fraser, was nearby when Bourne was hit. Hearing the blasts, he had broken with normal procedure and come up to see what was going on. Now he was the battalion commander, an ‘unwelcome variation,’ in Fraser’s view. He would later rise to the rank of major general, and his ability to deal with unwelcome variations would benefit the men under his command in another jungle war, in Vietnam. Fraser’s immediate concern was that the explosions presaged a Japanese counterattack, so he asked Bluey Whyte to bring down artillery fire further forward, onto Prothero 2, the likely forming-up point for such an attack.56 Whyte sent his observation officer, Captain Colin Stirling, up to the forward platoon and Stirling directed the shelling. The guns were connected via the tenuous signal line strung out down the approach spur and then along the Mene River valley back to the guns in the foothills near Dumpu. Whyte had carried a roll of cable up the ridge on his back to make this possible. The 25-pounders soon hammered out their salvos, directly towards, but staying just in front of the Australian positions. It was exceptional work from Stirling: the thickness of the jungle meant he had to range the guns by sound while also taking care not to expose the Australians to the shell blasts.57

‘I’m going to take the gun,’ Lieutenant Charlie Braithwaite told Captain Kevin Thomas. ‘Just settle down a bit,’ the canny Thomas advised, knowing that a hasty initial attempt had already failed. Thomas gathered all the available Bren gunners and told them to lay down concentrated fire on the enemy position while Sergeant Don McCulloch got hold of one of the blockbuster bombs. The plan was for him to move up to the bunker under the covering fire and fling the bomb inside.58

Fraser was also anxious for the next attack to succeed, so he had a Vickers machine gun brought up. Norm Sherwin had the gun positioned at the base of a tree to the side of the bunker, able to fire into the back door at an almost ninety-degree angle. Fraser now called out to Brodie Greenup, who was still hunkered down with some other men at the head of the track, in the line of fire of the Vickers. ‘Greenup, can you hear me?’ Fraser called. ‘Keep your men down.’ As the Vickers opened up, Fraser turned to Lieutenant Hughie Giezendanner and said, ‘Get in there and get that gun.’ Then there was another shout, again directed at Greenup. ‘Get your head down, Brodie, I’m coming through.’ It was Charlie Braithwaite.59

It was now 1700, and as the Vickers ceased firing, Melven ‘Nugget’ Robinson moved down into the gully with his Bren gun blazing from the hip, heading for the bunker door. Dick Lugge, a big country lad from Murgon, was up with Robinson, while McCulloch was on the left, trying to stay in defilade from the machine gun. Further back, Bob Davis saw it all unfold. As Robinson advanced, he unmasked one of the enemy LMGs and was stitched up across the chest. Davis could see the bullets popping out the back of Robinson’s shirt before the brave corporal collapsed to the ground. Seeing Robinson fall and the attack falter, McCulloch pulled the pin and flung the blockbuster out towards the gun bunker. In the confined space of the gully, the explosion was horrendous, and the LMGs outside the bunker fell silent.60

Lugge was the first to react, going for Robinson’s Bren and then rolling down to the base of the bank and firing from the ground point blank at the bunker door. Watching from further back, Braithwaite could see that a machinegunner in the adjacent bunker was targeting Lugge. He yelled a warning and Lugge moved like lightning, rolling to his right, drawing a bead on the support bunker, and firing at close range into the narrow embrasure. The machine gun fell silent, enabling others to rush up and fling grenades through the door of the mountain-gun bunker. The explosions and screams from inside told their own story. The nemesis had been silenced.61

On the previous day, after the gruelling approach march along the river valley, a weary Dick Lugge had sidled up to Drew Hunter. ‘Some bastard is going to pay for this, Drew,’ he said. Someone had.62

For the stretcher bearers and medical staff, the battle had only just begun. There were twenty-three stretcher cases at the regimental aid post that night. Their treatment was supervised by Sergeant John Palmer, who had dragged two of them back from under the blast of the enemy mountain gun himself. His job now was to keep the wounded men alive until they could be carried down off the ridge in the morning. That was a challenge for any one man, but for Palmer, who was riddled with malaria and should have been on one of the stretchers he tended, it was a heroic effort indeed.63

It took up to sixteen men to manhandle one stretcher down the side of the ridge. A standard Army stretcher was useless in such conditions, so the bearers made their own by using a hessian bag or blanket that would sag and keep the patient below the level of the side rails. The poles were cut from small trees and at least 4 metres long so there was room for many hands at each corner as the stretcher was passed up and down the steep slopes. The stretcher bearers carried machetes to fell the saplings, half-blankets for stretcher bases, and twine to bind to the poles. They worked quickly, dragging the wounded from under the shellfire and constructing the stretchers where they lay. Terry Wade had seen nothing to compare to the carnage at Prothero. He thought the bearers worked like scared rabbits to get the wounded out of the line of fire.64

Back at the 2/5th Field Ambulance dressing station at Geyton’s Post, forty-two casualties arrived on 22 January, every one of them wounded by the mountain gun.65 Captain Clarrie Leggett, the surgeon, worked until 0500 the next morning before taking a two-hour rest. ‘Call me at seven,’ he told Lloyd Tann. He then worked on fresh casualties all day and all night, not stopping until 0500 the following morning. Another thirteen casualties arrived on 23 January, making a total of fifty-eight. Leggett was so fatigued that at times he could not lift his feet out of the mud without assistance, yet he kept this up for three days and nights until he was relieved. For him, Operation Cutthroat was in fact forty-five operations.66

A surgeon at one aid post, perhaps Leggett, came out and chatted to some men who were on their way to the front line and had watched an operation he had performed. ‘You blokes must have great nerves to be able to slice a bloke up like that,’ one soldier said. ‘What about yourself?’ the surgeon said. ‘It’s not exactly a Sunday afternoon picnic to slice up Japs. And besides, a scalpel is sharper than a bayonet and you can’t put the Jap under ether.’67

Chilton’s three battalions now converged on the final Japanese redoubt in the Finisterres, at Crater Hill, which fell on 1 February. The remnants of Major General Nakai’s 78th Regiment, pressed by Brigadier Heathcote Hammer’s 15th Brigade, were soon in retreat to the coast. Madang fell on 24 April, abandoned by the Japanese as General MacArthur moved to isolate Lieutenant General Adachi’s entire army and take the war beyond New Guinea.