American operations

August 1943 to September 1944

Captain Akira Yamanaka knew that disaster was imminent. That mid-August morning, the Japanese Fourth Air Army intelligence officer learned that the American bombers were on their way to Wewak. But he did so when the bombers were less than 15 minutes away. Following heavy air attacks the previous night, most of the signals network was down and senior officers were absent at a staff conference. All Yamanaka could do was run to the flight line and yell a desperate warning. It was the beginning of the end for Japanese air power in New Guinea.1

In line with their change in strategy following the loss of the Papuan beachheads, the Japanese had decided to move the main base for air operations in New Guinea from Lae to the Wewak area. The Battle of the Bismarck Sea confirmed that this was a wise decision. After three new airfields were constructed around Wewak and another upgraded, the planes of the Fourth Air Army were flown in directly from Japan and the Philippines. The deployment of the Air Army also completed the shift in responsibility for air operations on mainland New Guinea from the Imperial Japanese Navy. Also learning from the well-planned Bismarck Sea battle, Lieutenant General George Kenney, the Allied air commander, realised that the destruction of the Japanese air arm at Wewak would require a coordinated approach that emphasised his low-level bombers. However, the Japanese commanders had the advantage, and they knew it: the Allies had no viable combat airbases for fighter escorts within close range of Wewak. And without fighter escorts, the Japanese fighters could make Kenney’s bombers pay a heavy price.

One of Kenney’s key men at this stage of the war was the tall Texan airfield engineer Lieutenant Everette ‘Tex’ Frazier, who had influence out of all proportion to his rank. Kenney placed great faith in Frazier’s judgement, and ended many a discussion on airfield site strategy by saying, ‘Well, Lieutenant Frazier has been there.’2 It was Frazier’s task to find a suitable site closer to Wewak. The airfields at Wau and in the Bulolo Valley were too restricted by the terrain and too well known to be used as major staging bases. But a rough bush strip built before the war held promise: it was in a relatively open area, at Marilinan, in the lower Watut Valley. Airfield construction equipment was flown in, and Lieutenant Colonel Murray Woodbury’s 871st Airborne Engineer Battalion began building the new strip in June 1943. Within months a new airbase named Tsili Tsili had sprung up in the jungle, and though Kenney feared that the name would come back to haunt him, by the time the Japanese discovered the base on 11 August, it was already operational.

On 17 August, six squadrons of P-38 Lightnings flew into Tsili Tsili. The fork-tailed fighters refuelled and then took off to escort five squadrons of B-25 Mitchells, which were already on their way from Port Moresby to Wewak. It was their first operational mission using long-range fuel tanks, and despite teething problems with the tanks, the ground-hugging Mitchells that made it surprised the Japanese defenders. After fifty heavy bombers had carried out high-level raids the previous evening, the Mitchells attacked the four airfields at low level, catching some 225 aircraft from the 6th and 7th Air Divisions on the ground. Hundreds of 10-kilogram parafrag bombs were dropped over the runways from low level, directly targeting the aircraft. Designed to break into tiny fragments when detonated, the bombs were attached to small parachutes to slow and straighten their descent and give the pilot time to get away. ‘A wicked little weapon’ was how Kenney described them.3

Lieutenant Garrett Middlebrook, who piloted one of only three Mitchells from his squadron to reach and attack Dagua airfield, northwest of Wewak, on the first day, later recalled the devastating effect of the low-level attacks: ‘God, it was unbelievable . . . The first twin-engine Sally bomber which my tracers poured into exploded and the concussion caused an identical plane alongside it to jump several feet into the air before settling back to earth where it too began to burn. I saw the tail section upon a third bomber disintegrate while the wing of yet another was shredded.’4

Though hampered by the weather, the attacks continued the next day, and the air battles were fierce. Ten to fifteen enemy fighters intercepted a flight led by Major Ralph Cheli, but with flames erupting from his right engine and wing, Cheli led the way across Dagua drome, strafing a row of enemy aircraft before instructing his wingman to take over the flight and ditching into the ocean. Cheli, who was captured, sent to Rabaul and later murdered by the Japanese, was awarded the Medal of Honor.5 After the first two days of air attacks, more than 150 aircraft had been destroyed, crippling Japanese air power in New Guinea.

The Australian war correspondent Peter Hemery went on one of the Wewak raids in a B-24 Liberator. He wrote that ‘The great force of planes seemed to stretch for miles, as indeed it did.’ But it was still a hellish battlefield. ‘As we crossed the coast the weather hit us. The plane bucked and jumped. The formation disappeared. I could only occasionally see our wingman, flying a foot away through the driving clouds and horizontal sheets of sleet and rain . . . One minute we’d be alone in that immensity of storm. The next, like a theatre curtain parting, we’d see the rest of our formation, straggling now . . . Mitchells were all over the sky . . . Zeros came a yell . . . sleek shadows moving so fast they made us seem to stand still.’ Hemery watched one of the Zeros attack. ‘He was a pretty plane, painted a bright green with his engine cowling painted pillar box red . . . Even the tracers twinkling from his wing guns looked pretty, until you realised that those bullets arcing by were meant for you . . . He almost seemed to hit our bomber before he pulled away.’ Unable to find a gap in the weather, Hemery’s Liberator turned for home.6

Kenney’s air offensive continued, spreading out to Alexishafen and Hansa Bay and building in intensity as new Allied airbases were opened at Nadzab and Gusap following the fall of Lae. Damien Parer, now working for the Americans at Paramount News, flew with the Mitchells on a raid to Wewak on 27 November. His plane was named Little Hell, and Parer wrote, ‘I had a feeling I might cop it today.’ The Mitchells came in low over the airfield, strafing and then dropping parafrags. As Parer filmed, the aircraft was hit; some hydraulics were shot away and the navigator was wounded, but it returned safely to base. Parer simply wrote, ‘I was rather excited.’7

The conquest of New Guinea’s airspace paved the way for the Lae, Ramu Valley and Huon Peninsula operations.

Following the success at Wewak, Kenney’s next target was Rabaul. This new air offensive was launched on 12 October by eighty-seven heavy bombers, 114 B-25 Mitchells and twelve RAAF Beaufighters, escorted by 125 long-range P-38 Lightnings. Kenney had thrown into the fight every plane he had that could reach Rabaul. The B-25s raised such a dust cloud taking off from Dobodura, the extensive airbase south of Buna, that the Beaufighters only reached their target at Tobera airfield, east of Rabaul, as the Lightning escorts returned. Mistaken for Japanese aircraft, the Beaufighters were fired on by the Lightnings as well as by the enemy fighters, and one Beaufighter was shot down.8

Kenney wrote: ‘This is the beginning of what I believe is the most decisive action initiated so far in this theater. We are out not only to gain control of the air over New Britain and New Ireland but to make Rabaul untenable for Jap shipping and to set up an air blockade of all the Jap forces in that area.’9 After his experience at Wewak, Peter Hemery accompanied a high-level pattern-bombing mission targeting ships in Rabaul’s Simpson Harbour. Sitting at the navigator’s table just behind the pilot, Hemery wrote: ‘We levelled, straightened for the bomb run—minutes seemed to go by before the first of the flak burst, then a continuous menacing curtain stained the crystal blue sky.’ As each flight of Liberators dropped their bombs and banked away, another flight took their place. Hemery looked down at the harbour as ‘a bunch of six naval vessels moored alongside one another just vanished in a flash, brilliant even from that height . . . Then a huge mound of flame, smoke and debris arose from the water.’10

Captain Joe Stevens watched as a Japanese cruiser lowered its main guns. He didn’t hear the guns fire; he just saw the yellow flash before his plane passed over the warship. Stevens—an Australian air liaison officer working with the Mitchells of the US 499th Bomb Squadron, the ‘Bats Outa’ Hell’—was crouched down behind the pilots on a bombing run across Simpson Harbour. On this day, 2 November, the Mitchell bombers had wreaked havoc. Coming in low over the ridge behind Rabaul, they had dropped to almost sea level to carry out their attacks under the cover of smoke and phosphorus bombs.11

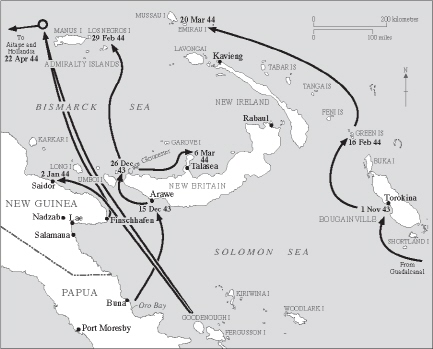

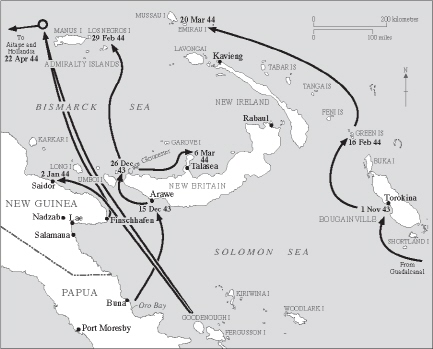

The attacks on Rabaul in October and November had lessened the air threat, and for good reason. Once the US Marines made their first landing on Bougainville on 1 November 1943, the Japanese naval air arm at Rabaul was unable to sustain a challenge against the landing force. As the next phase in a series of operations to isolate Rabaul, collectively known as Operation Cartwheel, General MacArthur now planned further landings on West New Britain to secure the eastern shore of the Vitiaz and Dampier Straits. Though there was much fighting to come on the ground in New Guinea, once Rabaul was isolated, the Japanese troops in New Guinea could no longer be effectively supplied, reinforced or provided with air support, and Allied amphibious operations were no longer at risk from significant Japanese air or naval action.

The way Kenney had organised his resources and implemented his strategies had a lot to do with his drive and his ‘can-do’ attitude. The Australian reporter George Johnston wrote, ‘He is dynamic, and he thinks, and the sentence he hates more than any other is, “It can’t be done!”’12 In Kenney, MacArthur had someone he could trust to carry out the mission of clearing the Japanese from New Guinea as soon as possible to open the way to the Philippines. On 4 August 1942 Kenney had replaced Lieutenant General George Brett, in whom MacArthur had no confidence. ‘MacArthur is prone to make all decisions himself,’ Brett wrote in a parting letter to Kenney. ‘Commanders are not conferred with prior to either major or minor decisions.’ According to Brett, Vice Admiral Herbert Leary, the naval commander, and General Blamey, the land forces commander, had a similar opinion of MacArthur. The Supreme Commander had no control over the three men’s appointments, but he did control their fates. He replaced Leary with Vice Admiral Arthur Carpender in September 1942, and Blamey would be increasingly marginalised as 1943 progressed. Although MacArthur was less than satisfied with his chief of staff, Lieutenant General Richard Sutherland, no one on hand was considered qualified to replace him. MacArthur told Kenney that Sutherland ‘is a brilliant officer whose ego is ruining him. He bottlenecks all action over his own desk.’ In the Papuan campaign, the Australian commanders found the ‘unpopular and sarcastic’ Sutherland very difficult to work with but, as the war developed, so did the working relationship. It had to.13

US Operations: November 1943–April 1944

On 15 December, the Americans landed at Arawe, at the south-western end of New Britain. This was the fourth operation for what was termed ‘MacArthur’s amphibious navy’ and the first opposed landing in which American assault troops were used. Vice Admiral Daniel Barbey, commander of the Seventh Amphibious Force, was as adept at utilising MacArthur’s meagre naval forces as Kenney had been with the air arm. At a time when the demand for amphibious troops from Europe and the Central Pacific seemed insatiable, Barbey had cobbled together the means to advance in great leaps around the New Guinea coast. Like Kenney, Barbey had a ‘can-do’ attitude. A good example was his agreeing to convert one of his LSTs to a first-aid ship with seventy-eight hospital beds. One of Barbey’s medical officers did the design, the work was carried out in Sydney, and the vessel operated throughout the war. Nine months after the conversion, Barbey received notification from the Navy Department denying his request.14

Having a blue-sea amphibious force was one thing, but using it judiciously was another. Captain Charles Adair, Barbey’s planning and operations officer, later summed up MacArthur’s strategy for amphibious operations as ‘to go where the Japanese were not and hit them where they didn’t expect it.’ Adair considered that the time it had taken to break down the Papuan beachheads had a profound effect on MacArthur’s thinking. As Adair observed, ‘He decided that the only way to do it was to bypass these people, cut off their supplies, and establish yourself with a base, jump from there and bypass another group, and cut them off.’15

Following heavy air support and naval gunfire, the Arawe landing was made by two squadrons from the 112th Cavalry Regiment—some 1100 men—and 500 support troops. The Australian landing ship Westralia, carrying eighteen landing craft, took part alongside the USN landing-ship dock Carter Hall, which carried thirty-nine Buffalo and Alligator amphibious vehicles. It was Barbey’s first use of attack transports. The Westralia was the first of three merchant cruisers converted to that purpose in Australian shipyards. Along with the Manoora and Kanimbla, it would prove a vital component of Barbey’s navy for the remainder of the war. The Westralia and Carter Hall unloaded before dawn as the first shots rang out from the landing beaches. The fire was from an ancillary landing by a unit of Rangers which had faltered in the heavy surf and been beaten off by the Japanese. The main landing went in as day broke, and the two companies of Japanese troops defending the area soon withdrew to the east.16

Damien Parer, who left the Westralia before dawn and headed for the beach in one of the landing craft, wrote that ‘It was half light and the Alligators and Crocodiles can be seen ahead of us with their wakes all white.’ These tracked landing craft kept the US Cavalrymen safe from fire until they reached the beach and, if necessary, beyond. Despite fighter cover, enemy aircraft from Rabaul caused the most concern. Parer was caught up in a late-afternoon raid: ‘The AA was giving them merry hell . . . I thought one of the bombers had dropped a bomb towards us and I went to ground. It floated slowly down . . . It was part of a bomber that had apparently disintegrated in mid air.’17

Two other war correspondents, Harold Dick and Pendil Rayner, were also at Arawe. Dick had landed with Parer but left soon after. On 19 December, the twenty-six-year-old West Australian journo was killed along with thirty others when a Dakota transport plane crashed northwest of Rockhampton. Only a week later, Rayner was killed when the B-17 bomber he was flying in—en route to cover the landing at Cape Gloucester, on the western tip of New Britain—crashed on takeoff at Port Moresby. Parer survived Arawe and his own flight to Cape Gloucester, where he watched the landing from above: ‘The glow of dawn is seen over Gloucester . . . Great masses of bombs cascade down from B24s . . . Naval shells landing by the shore . . . Mitchells fly beneath us and lay a smoke screen . . . LCTs with white wake showing going in, others are seen coming out.’18

With Japanese attention diverted to Arawe, elements of the 1st Marine Division, the veterans of Guadalcanal, landed at Cape Gloucester on 26 December. As at Arawe, a heavy air and naval bombardment, including shelling from the RAN ships Australia, Shropshire, Arunta and Warramunga, preceded the landing. Though Japanese resistance on the landing beaches was minimal, the US destroyer Brownson was sunk by Val dive-bombers from Rabaul. The Japanese troops were focused on defending the airfield at Cape Gloucester, or Tuluvu, as they knew it, so the Marines landed further east before advancing along the beach supported by Sherman tanks. Beyond the narrow beach, the Marines came up against other enemies: thick jungle and muddy swamps fed by regular heavy rain. The airfield was secured on 29 December.19 Japanese battalions under Major Masamitsu Komori were sent from Rabaul and Cape Bushing to attack the Arawe beachhead, but the Americans were well entrenched by the time they arrived. After a series of costly and fruitless attacks, Komori’s remnants withdrew to Rabaul in February.20

Although the original Cartwheel plan as set out in March 1943 had the capture of Rabaul as its aim, MacArthur had persuaded the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the same result could be achieved by isolating the Japanese base. Resources would then be available for operations towards the Philippines and beyond, MacArthur’s focus since March 1942, when he had left the Philippines vowing to return. His strategy was agreed to in August 1943.21 However, the Allied command was still concerned about the threat from Rabaul and Kavieng. Kenney’s bombers continued strikes against Rabaul well into February 1944, and US carrier-borne aircraft struck at Kavieng on 25 December and 1 January.22

Having kept his powder dry for so long as he built up his air and naval resources, MacArthur now began his push west along the northern coast of New Guinea. American detachments had already landed on Umboi and Long Islands, thus fully securing the Vitiaz Strait. Then the American invasion convoy that landed troops at Saidor on 2 January 1944 consigned the Japanese on the Huon Peninsula to the horrors of retreating to Madang across the Finisterre Range. Unfortunately the Americans, whose objective was to establish air and naval facilities at Saidor, were content to count the enemy troops heading into the ranges without helping the Australians stop them. Nonetheless, within two weeks of the landing, the airfield at Saidor was fully operational and a naval supply base established, both ready to support operations further afield.23

One more objective needed to be taken to ensure the isolation of Rabaul: the Admiralty Islands, off the north coast of the New Guinea mainland. A secondary advantage was that Seeadler Harbour would serve as an excellent anchorage for future amphibious operations. Kenney’s airmen soon rendered the two Japanese airfields inoperable, and intelligence estimated that few troops remained on the islands. With a good chance of rapid victory, MacArthur agreed to land a minimal force on Los Negros Island. What the Americans did not know was that Colonel Yoshio Ezaki had ordered his troops to conceal their presence by neither moving nor firing during daylight.24

Watched by MacArthur from aboard the cruiser Phoenix, a force of 800 men, including a 500-man squadron from the 5th Cavalry Regiment, landed on Los Negros on 29 February 1944. Concerned for their flanks, the Cavalrymen stayed in their shallow beachhead perimeter. When the Australian war correspondent Frank Legg, who had seen active service in the Middle East, went in with the second wave, his landing craft came under considerable fire at the narrow entrance to Hyane Harbour. Once ashore, Legg met up with the Australian war photographer Frank Bagnall, who reckoned there were no Japanese ‘within a mile of us.’ He and Legg proceeded to move across Momote airfield; only after they had returned did the 5th Cavalry move out to ‘capture’ the airfield.25

Back at the Hyane Harbour entrance, Japanese reinforcements had made further passage difficult. Destroyers and minesweepers under the Australian naval captain Emile Dechaineux tried to force the entrance but did not have the firepower to take on the enemy guns. Heavy Japanese attacks on the night of 3 March were held off, thanks in large part to the intricate American defences, well constructed by the engineers, the fighting Seabees. They also manned the lines: nine of seventy Americans killed that night were Seabees, and it was now obvious that more combat troops were required. On 7 and 9 March, more troops, including units from the 7th Cavalry Regiment (of George Custer fame), were landed in Seeadler Harbour, but Los Negros was not totally secured until May.26 The next objective was the airfield at Lorengau, on the adjacent Manus Island.

On 11 March, a twenty-six-man patrol was sent to Hauwei Island, off the north coast of Manus, to look for suitable artillery sites. Warrant Officer Alf Robinson, from the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit, and two native guides would lead the patrol, which went across to Hauwei on a landing craft escorted by a PT boat. The quick thinking that had saved Robinson at Tol Plantation would again be tested here.

Major Carter Vaden led the patrol ashore without interference, but when he threw a grenade into an enemy bunker, concealed Japanese mortars and machine guns opened fire on the patrol and on the craft offshore. The PT boat was hit and withdrew, while the landing craft went in and picked up five men, including Robinson and his native police assistant. After embarking another group, the boat pulled back, but it was hit by a mortar round and began taking on water. Eight Americans, including Vaden, were killed and fifteen wounded, the entire landing craft crew among them. Another PT boat, covered by the Arunta, was sent to rescue the survivors, who had spent three hours in the water. The next day Robinson, notwithstanding severe sunburn from his sojourn in the ocean, guided a larger force in to capture Hauwei. After a fierce firefight, the Allied troops counted forty-three dead Japanese; Hauwei now became an artillery support base for the invasion of Manus Island.27

Later, Robinson was aboard a PT boat with Captain ‘Keith’ McCarthy, the former Administration officer who had helped bring him out of New Britain in 1942. Near Manus, the boat approached an outrigger canoe carrying nine Japanese soldiers, and the PT’s crew beckoned for them to swim across. Three of the Japanese were on the outrigger’s platform when one produced a grenade, struck it on his helmet and ended the three men’s lives. Two others with grenades were shot, while another disappeared into the sea. The last three dropped their grenades and swam to the boat. When one asked, ‘When you kill us?’, McCarthy replied, ‘No can kill you,’ then spied Robinson looking down at the scars on his wrists from Tol. Later, one of the prisoners jumped overboard to drown himself, but he kept surfacing, driven by the natural instinct to survive. Finally Robinson, driven by his own appreciation of the value of life, dived in and pulled the hapless prisoner back on board.28

On 15 March, the 8th Cavalry Regiment landed on Manus, and the airfield at Lorengau fell three days later. Damien Parer had seen dead Japanese before, but this was a vision of hell. ‘I think they have been ordered to annihilate us or not return,’ he wrote. ‘I heard and saw the debris flying when the last of them blew themselves up.’ Later it got worse. ‘Over 70 dead Japs packed like sardines, disembowelled, heads missing. Some still dying.’29

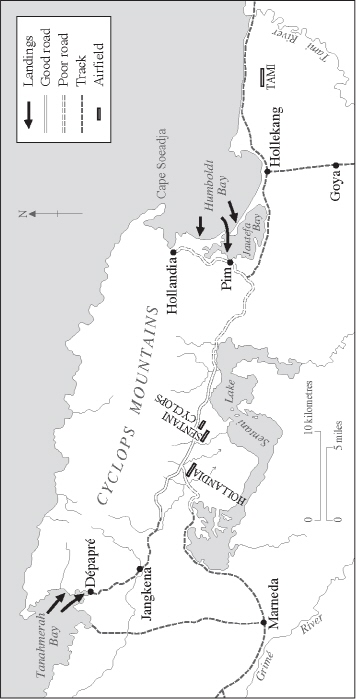

On 20 March, Emirau Island, 120 kilometres northwest of Kavieng, was occupied unopposed, and by the end of April two airfields had been constructed there. With Kavieng and Rabaul isolated, MacArthur could now make a great bound towards the Philippines. Having convinced the Joint Chiefs of Staff that Wewak should be bypassed, he planned to strike Hollandia (modern-day Jayapura), just across the border from Wewak in Netherlands New Guinea. Apart from isolating the Japanese Army in New Guinea, MacArthur wanted the prime anchorage of Humboldt Bay and the Lake Sentani airfields for his drive towards Japan.

Intelligence made the Hollandia decision possible. ULTRA decrypts, the decoded Japanese naval and Army communications, had already played an important part in New Guinea operations. ULTRA’s first success had been to expose Japanese intentions during the Papuan campaign, particularly the planned invasions of Port Moresby and Milne Bay. Later plans to reinforce Lae had been uncovered by ULTRA and then undone by the Battle of the Bismarck Sea. ULTRA had then kept MacArthur informed of the air buildup at Wewak, which had been so efficiently nullified by Kenney’s air arm. Now it gave MacArthur the priceless advantage of knowing that Hansa Bay was being reinforced and would be a tough nut to crack. The same was true of Wewak, but the decrypts confirmed that both Aitape and Hollandia were weakly held.30 The Japanese commanders were thinking in small steps, while MacArthur was planning a great leap.

The Australians played a major part in this intelligence coup. When the radio platoon from the Japanese 20th Division headquarters had pulled out from Sio in the wake of the Australian advance, its men had to carry the heavy components of the radios. However, a large trunk containing all their code books and other cipher material was left behind, buried in a nearby creek. It was discovered by Australian sappers sweeping the former headquarters site for mines and sent back to Australia, where the documents were painstakingly dried out and analysed. The cipher keys gave the Allies access to crucial intelligence on Japanese Army strength and plans in New Guinea.31

So MacArthur would boldly strike for Hollandia six months ahead of the originally scheduled date. Though the operation’s code name, Reckless, may have indicated otherwise, MacArthur had the intelligence and the resources to succeed.

Another element of the intelligence war was Captain Gwynne ‘Blue’ Harris. The balding redhead, a member of the Australian M Special Unit, had operated behind enemy lines on New Britain, at Finschhafen and along the Rai Coast, southeast of Madang. His next mission would be to lead a two-week patrol behind enemy lines at Hollandia. The eleven men of Harris’ party—six Australians, four New Guineans and Sergeant Launcelot, an Indonesian interpreter—were to assess the proposed landing beaches at Tanahmerah Bay, 50 kilometres west of Hollandia. Another party under Captain Claude Millar was landed inland about 160 kilometres to the south in order to relay radio signals from Harris.32

Lieutenant Ray Webber, who had previously served with Harris, was his second-in-command. The initial five-man reconnaissance group left the US submarine Dace on the night of 23 March, but rough weather meant a difficult start to the operation. Both their rubber boats overturned in the surf, and the walkie-talkie was lost. Then a fire flared up at a nearby native hut, indicating that the landing had been seen. Harris and Launcelot went to the hut and were told that the nearest Japanese troops were 5 kilometres away to the west. A suspicious Harris decided to abort the operation, so he had Webber send the washout signal to Dace by flashlight: the rest of the party were not to land. However, Webber could not get acknowledgement of his signal, and when he climbed a hill to resend the message, he saw that the other two rubber boats were already on the way.33

Harris gathered his men and what weapons and supplies remained and headed inland, intending to reach Millar’s party. He took a young man from the hut as a guide, but when the youth went missing, he knew his party was compromised. The natives back at the hut, hundreds of kilometres behind Japanese lines and with little reason to throw in their lot with Harris and his party, had informed on them once they moved inland. Next morning, as the party reached a wide patch of kunai grass, they heard voices from their rear. When Webber went back, he spotted a line of enemy troops headed his way. As Harris led the rest of the men across the kunai towards the jungle, the Japanese opened fire. The four New Guinea men in the party reached the scrub, and Julius MacNicol, Philip Jeune, Launcelot and Webber hid in the kunai grass.Harris decided to fight, John Bunning and Greg Shortis joining him in a last-ditch attempt to hold off the Japanese and gain time for the others to escape.34

The three Australians were outgunned by the Japanese troops, who were well armed with light machineguns and mortars. Bunning and Shortis fought for four hours before both were cut down. MacNicol, who had crawled up to the edge of the jungle, beckoned Harris to join him, but Harris stayed till the end. Thrice wounded, his pistol empty, he was finally captured, propped up against a tree and roughly interrogated. He knew the invasion convoy would soon be off the coast, and if the Japanese found out, there would be many more lives lost than his. That life was finally taken at the end of a bayonet.35 He never talked—a brave man, Blue Harris.

Launcelot hid for four days, licking dew from the grass to survive while the Japanese searched the area. He then met up with a local native who fed and hid him. Once the Americans landed, he made his way back to the beach and took a canoe out to a destroyer; he later told his story to Lieutenant General Eichelberger. Jeune and Webber also made for the coast. When Jeune’s legs gave out, Webber took him to a hut for shelter, but as they reached it, a sword-wielding Japanese soldier charged them. Jeune was badly cut about the head and arms as he tried to fend off the blows. Afraid to fire his weapon, Webber punched the man before thrusting the pistol into his midriff and firing. He then grabbed the sword and finished the job. The two men kept on for the beach and finally met up with the Americans. Julius MacNicol was the last Australian in, after thirty-two days. Two of the New Guinea men had headed for Saidor, 650 kilometres away. One, Buka, died on the way; the other, Yali, made it to the American lines at Aitape.36

Though MacArthur would have naval air support for the Hollandia operation, he would also need his own fighter planes on hand. It was therefore decided that an ancillary landing would be made at Aitape, midway between Wewak and Hollandia. In the lead-up to the operation, Kenney based new long-range P-38J Lightning fighters at Nadzab, and these escorted a series of heavy bombing raids on Hollandia, the most devastating of the war in New Guinea. As at Wewak, the Japanese thought their airbase at Hollandia was out of range of escorted bombers but once again they had been trumped by American ingenuity. During the first raid, on 30 March, sixty-one Liberators dropped almost 6000 fragmentation bombs over the three airfields, targeting aircraft, fuel dumps and anti-aircraft positions. When the airfields were later captured, 340 Japanese planes were found wrecked on the ground, another sixty having been shot out of the air. On 4 April, a Japanese seaman wrote, ‘We received from the enemy greetings which amount to the annihilation of our Army Air Force in New Guinea.’37

Not all the air raids against Hollandia went to plan. For over 300 aircraft in the eighth and final raid on Sunday 16 April, things began well enough, but by day’s end it would be known as Black Sunday. A strong force of fifty-eight Liberators, forty-six Mitchells and 118 Havocs, escorted by Lightnings, took off for Hollandia.38 Most flew out of Nadzab, with three Havoc squadrons flying from Gusap and another two from Saidor. The bombing went well, but as the aircraft headed home a massive storm front rose in their path. One of the Lightning pilots, Carroll Anderson, wrote in his diary, ‘As the black smoke pall over Hollandia fell behind, it became obvious that thunderheads loomed ahead . . . It stretched from the mountains to the south and to the north as far as we could see.’39 The route back into the Ramu Valley and on to Nadzab was blocked.

There had been weather warnings before the raid, but the imminence of the Hollandia invasion made the risk seem worthwhile. Now the planes could not return the way they had come. The first Liberators headed back along the north coast only to find that Finschhafen was also clouded in, but at least one bomber got down in Lae. Most landed at Saidor. The Mitchells came in first. Landing in the rain and skidding across the wet Marsden steel matting, the first two collided just as a Liberator also landed. A third Mitchell came in and slewed into an embankment, while a fourth slammed into a Lightning coming down from the other direction, blocking the strip. Men rushed out to clear the wreckage and to rescue two of the crew. As they did, another Lightning, running on vapours, belly-landed and skidded through the wreckage. The pilot survived, but the airfield was a shambles.40

Havoc bombers circled overhead waiting for the wreckage to be cleared. The first one down clipped some wreckage and lost a few metres off its right wing. More followed, guided in through the wreckage and in some cases adding to it—often while taxiing. Lieutenant Stan Northrup’s Lightning landed on top of a slower Mitchell, but he gunned the engines at the last moment and leap-frogged to land. Another Lightning came down just as a Liberator landed the other way, the Lightning pilot hitting the brakes and side-slipping his aircraft around the bomber.41

Some aircraft landed on the nearby bush strip at Yamai, others in the sea off the coast. More put down in the swamps and other small dirt strips behind the coast. By day’s end twenty-six planes had been destroyed in crash landings and eleven more were missing. Fifty-three airmen were killed or missing. Kenney later wrote, ‘It was the worst blow I took in the whole war.’42

There were 164 ships in the invasion convoy, a ripe target indeed for an air attack, but no attack came. Kenney’s bombers had seen to that while the temporary presence of the US carrier fleet ensured that any such attack would be harshly dealt with. This was the seventh and largest operation to date for Barbey’s Seventh Amphibious Force. On the night of 21 April, the convoy split into three parts for two landings at Hollandia and another at Aitape. The main objectives at Hollandia were the airfields behind the Cyclops Mountains. In what the Americans might have termed a squeeze play, there would be a landing at either end of the range, at Tanahmerah and Humboldt Bays and the troops would advance from east and west to secure the three Japanese airfields. The ABC war correspondent John Hinde, the passionate film reviewer of later years, wrote, ‘The incredible realisation that the Japs didn’t even suspect we were coming came only in the last hour of darkness on D-Day morning.’43

Two RAN heavy cruisers, Shropshire and Australia, and two RAN transports, Kanimbla and Manoora, took part in the Tanahmerah Bay operation. Though the landings here were unopposed, the aerial photos failed to show that there were extensive swamps starting only 30 metres behind the main landing beach. The ground was passable only by lightly equipped infantry, and the Americans had everything but. The supplies had to be piled up on the narrow beach and then transshipped to a second beach, near Dépapré, at the head of the bay. Later landing waves were diverted to Humboldt Bay.44

Despite the confusion of the Dépapré landings, Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Clifford’s 1/21st Battalion immediately set off up the rough trail to Lake Sentani and the airfields. The advance was unopposed, and Clifford had reached Jangkena, about 13 kilometres inland, by nightfall. The other two battalions followed before torrential rain on 23 April prevented supply trains from getting through from the beach. The inclement weather also prevented an airdrop.

At Humboldt Bay, Westralia had been one of the thirty-three ships involved in the landing. MacArthur watched from the cruiser Nashville as the warships opened fire at 0600 and the troops landed at 0700. All day the warships supported the landing, their heavy fire sending most of the defenders scurrying inland. John Hinde wrote, ‘Twenty minutes after the first troops touched land word is flashed back that the main landing beach is clear.’ He noted one reason why ‘they met silence instead of gunfire’:

the Japanese defenders had chosen death rather than defeat even before the initial bombardment from the sea had ceased. They crouched along the walls of the pillbox, knees drawn up, heads hunched forward and a bullet hole in the centre of each forehead. The officer who had shot them lay before his men disembowelled in ritual fashion by his own sword.

Next day was sunny and Humboldt Bay was a lovely ruffled blue dotted with ships and criss-crossed with the wakes of high speed landing craft . . . In spite of the din it was hard to take the war seriously. 45

Hinde then caught a boat ride across to newly captured Hollandia. ‘There was a thin haze of smoke in the foothills beyond the town and the crash of bazooka and mortar fire came solidly down the valley. But Hollandia itself was a scene of peace and red and white neatness that would have delighted the heart of any Dutchman.’46

On the main landing beach at Humboldt Bay, there was a sizeable Japanese ammunition dump. Just after dusk on the second night, a lone Japanese plane came over and dropped two bombs and an incendiary right on top. The narrow beach had the sea on one side and a swamp on the other, so when the ammunition in the dump started exploding, the beach was cut off. Shells cooked off and exploded every few seconds, and occasionally there would be a massive blast. Hinde was in a group of men who were cut off and pulling back towards the point. ‘I remember looking back and suddenly seeing the fire clawing up the beach after us in an arching rain of red tracer bullets, rockets and glowing fragments,’ he wrote. When Hinde left for home two nights later, the dump was still burning.47

By then, the airfields were in American hands. The advance from Humboldt Bay had been difficult, with the mud so deep that even the amphibious tractors got bogged. When the track was hemmed in by the ranges to the north and Lake Sentani to the south, the amtracs—amphibious tracked landing vehicles—took to the lake. The two thrusts made contact late on the afternoon of 26 April.

Operation Persecution, the landing at Aitape, was also made on 22 April. Tadji airfield was soon secured, and RAAF No. 62 Works Wing started working on it that same day. Work continued under floodlights throughout that night and the next, and the 1250-metre fighter strip was available on the morning of 24 April. The first twenty-five Kittyhawks from RAAF No. 78 Wing flew in that afternoon, and the rest arrived the next day. Steel Marsden matting was then laid down, and the strip was operational on 28 April. The RAAF engineers then moved across to the bomber strip to assist the two US aviation engineer battalions already working there.48

On 2 May, General Adachi’s Eighteenth Army had been ordered to move west from Wewak, bypassing Aitape and Hollandia. Adachi knew better than anyone that such a move—across wild rivers and through the rugged interior—would destroy his army, and the orders were cancelled two weeks later. Though Adachi had 50,000 men at Wewak, only about 8000 were trained infantrymen, most of the remainder being supply troops. He would attack Aitape with 15,500 men, use another 15,000 as supply troops, and leave 20,000 at Wewak. The move west would be by land, as any boats or barges were rapidly jumped on by Allied air or naval craft: on the night of 26 June alone, American PT boats sank fifteen barges near Wewak.49

After the travails of the Saruwaged and the Finisterres, Masamichi Kitamoto had just completed another testing trek across the coastal plains of the Ramu and Sepik Rivers. ‘We sank up to our knees in the marshes which continued endlessly,’ Kitamoto wrote. ‘Mangrove and other swamp bushes obstructed the way. It was like walking in a steam bath. Even in the humid jungles, this is the most unhealthy and difficult place for man to live . . . The whole army was in rags and many of the men were bare footed as we arrived in Wewak. They were no longer a fighting force.’ Now General Yoshihara gave him another task, to walk the 200 kilometres to Aitape and reconnoitre the American defences there. ‘You are the only one I can depend on,’ Yoshihara said.50

The eastern flank of the American perimeter at Aitape rested on the Driniumor River. Patrols had pushed east from there and found indications that Japanese reinforcements were moving into the area, though these could hardly be termed fresh. Remnants of the Japanese 20th Division, having fought at Salamaua, Lae, Finschhafen and Shaggy Ridge, had now made their way to the area. Some of the 41st Division units were in better shape, having only had to trek up from the Madang area. Both divisions faced further misfortune when Lieutenant General Shigeru Katagiri, the 20th Division commander, was killed in a bombing raid along with six staff officers of the 41st Division. The rest of the troops, usually travelling by night, were harried all the way from the air.

By mid-June 1944, MacArthur, who had access to ULTRA decrypts and captured documents detailing the Japanese operation, had decided to reinforce the Aitape perimeter. Indications were that Adachi would attack with 20,000 men and another 11,000 in reserve. The American commander of XI Corps, Major General Charles Hall, strengthened his forward positions, emplaced his artillery, built a fall-back line and waited.51

On the night of 10 July the Japanese came. At midnight the companies of I/78th Battalion, the veterans of Shaggy Ridge, attacked in two or three screaming waves across the Driniumor River. Defending the west bank were two companies of the US 128th Regiment. That river and barbed wire slowed the attack, and the defensive artillery concentrations soon reduced the Japanese battalion from 400 to thirty men. Captain Emory Peebles, a forward artillery observer, noted: ‘I observed one bunch coming down the river and called on our guns for support. The first salvo of shells landed right in the middle of them, blowing some to the tops of trees and when the smoke cleared at least 25 were lying dead on the river bed.’52 The Japanese kept at it, throwing in troops from the 80th and 237th Regiment until they had punched a 1200-metre-wide gap in the line. The Americans responded to the threat with more concentrated shelling and attacks on both sides of the lodgement.

Meanwhile, Major Iwataro Hoshino’s Coastal Attack Force, supported by artillery, moved against the American perimeter on the coast. The heavy American guns soon prevailed. It took longer to deal with the main inland force, and the fighting went on for many weeks, but when it was over, Adachi’s army was broken. On 3 August, he ordered a withdrawal, having lost almost half of the 20,000 men committed to the fight.53 After the battle, the ABC war correspondent Haydon Lennard went to the Driniumor River, where ‘scores of enemy bodies bloated by the tropical sun are floating down the stream and the stench from the eastern bank is a continuous reminder that hundreds more are lying there in jungle undergrowth.’54

In the full context of the Pacific war, the Japanese attack at Aitape was insignificant. By mid-August 1944, MacArthur had already moved on from Hollandia, seizing Wakde Island and Sarmi before landing on Biak and Noemfoor Islands, off the north coast of Netherlands New Guinea. New airfields had already been built, more were in construction, and the threat to the Philippines was immediate. New Guinea was now a backwater.

Peleliu, a nondescript island in the Palau group about 1000 kilometres north of New Guinea, was another stepping stone on the way to Japan. Damien Parer landed there with the US Marines in September 1944, and as they fought across the barren sun-parched airfield, he shot his last roll of film. Just as he had done with the Australian commandos along the ridges above Salamaua, Parer stalked the front-line soldiers with his camera. Before his Wewak air-raid assignment the previous November, Parer had prayed that Our Lady would protect him ‘not only from death but if I was to die to do it well.’ He did it well.55