Bougainville

November 1944 to August 1945

It was 11 October 1945, and the war had been over for nearly two months. Tired of waiting to go home, Peter Pinney was leaving Bougainville the way he had come, cadging an unauthorised plane ride. As he sat under the aircraft wing that night waiting for the morning flight, he wrote: ‘Never again Bougainville! You’ve seen the last of me. They’ll never con me again to wriggle in your slime and rot and dust and wet monotony. A toss-up which I hate most—that mongrel island, or the mongrel animals we fought amid all that mass of wet forest and thorns and moccas and palms and silence and suddenness and gut-ache and mossed trees and everlasting bloody mud. I won’t be back: not till hell freezes and the devil wears skates.’1

While operations in General MacArthur’s South West Pacific Area had seen the tide turn in New Guinea, Admiral William ‘Bull’ Halsey, the South Pacific Area Commander, had orchestrated the drive through the Solomon Islands. After the successful conclusion of operations on Guadalcanal, Halsey had landed forces on New Georgia on 30 June 1943. Progress was slow, thanks to the punishing jungle terrain as well as the Japanese defenders. The American command had thought one division would be sufficient for the operation, but in the end, elements of four divisions were needed to secure the Solomons. In September 1943, the stubborn Japanese commander, Major General Noboru Sasaki, had evacuated 9400 of his men to the island of Bougainville.

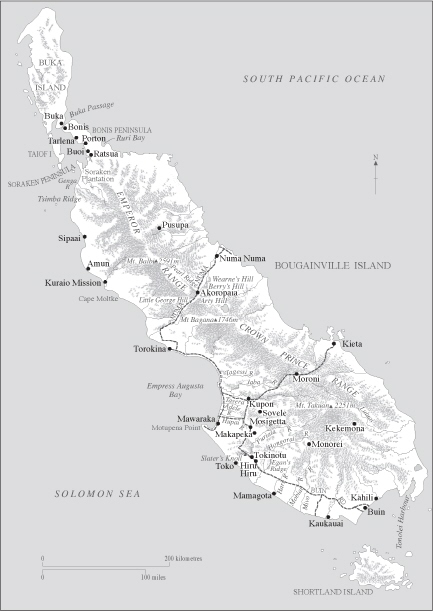

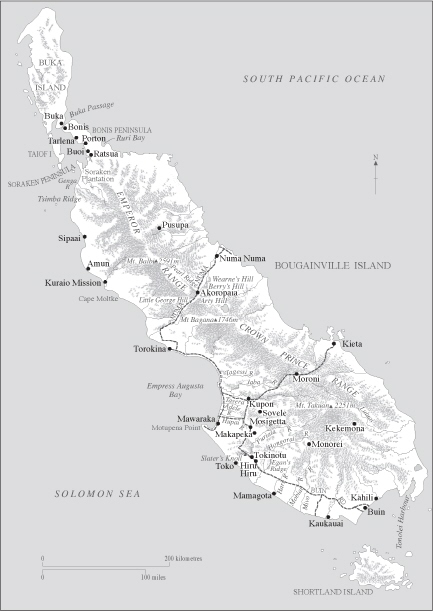

Following the US Command’s decision to isolate rather than capture Rabaul, Halsey decided to ‘contain and strangle’ the Shortland Islands and Southern Bougainville from New Georgia. However, it was still important to make a landing on Bougainville to build airfields for the projected operations against West New Britain in late 1943. The coastal plain at Cape Torokina, only lightly held by the Japanese, was selected as an ideal airfield site. Torokina was also hemmed in by mountains and coastal swamps, making it difficult for the strong Japanese forces in Southern Bougainville to threaten the landing.

The spine of Bougainville Island was formed by two jagged mountain ranges that included a pair of active volcanoes, Mount Bagana and Mount Balbi. The island was defended by Lieutenant General Haruyoshi’s Hyakutake’s Seventeenth Army, most of whose 37,500 soldiers and 20,000 sailors were deployed in the south around Buin and the Shortland Islands. The rest were focused at Buka and Kieta.

The American 3rd Marine Division landed at Torokina on 1 November 1943 and, aided by strong air cover, soon overcame limited but fierce opposition. The Japanese Navy reacted quickly. A task force of four cruisers and six destroyers under Admiral Sentar mori immediately left Rabaul and headed for the beachhead. Warned by reconnaissance aircraft, Admiral Aaron Merrill’s task force of four cruisers and eight destroyers intercepted Omori’s ships in the early hours of 2 November. With radar guidance, the American destroyers closed in and loosed their torpedoes while the cruisers stood off and fired their 6-inch guns, before rapidly changing station to avoid enemy torpedoes. The Japanese light cruiser Sendai and the destroyer Hatsukaze were sunk, while one of Merrill’s destroyers, Foote, was badly damaged by a torpedo. With another four of his warships damaged, Omori withdrew his ships to Rabaul. The Japanese sent four heavy cruisers and more destroyers from Truk to make a second attack, but they were caught by a US carrier strike at Rabaul on 5 November and not sent into battle. Despite heavy air attacks from Rabaul-based aircraft, the lodgement at Torokina was safe.

By March 1944, the Americans had three operational airfields and 62,000 troops at Torokina. Their perimeter extended in a semi-circle about 10 kilometres deep, with patrols operating further afield on the approach tracks. By this time, General Hyakutake had also concentrated a force in the hills around the American perimeter, but with Rabaul now neutralised as an air and naval base, he was on his own. After organising his force into three detachments and an artillery group, Hyakutake struck just after midnight on 8–9 March as the rain fell. American firepower did its job, and over 5000 of Hyakutake’s men were killed and another 3000 wounded for the loss of only 263 American defenders. It was carnage.2

One of the highest forms of courage is to save the lives of others at the risk of one’s own. What Corporal Sefanaia Sukanaivalu did on Bougainville went beyond courage. Suka, as he was known, had arrived at Torokina with the 3rd Fijian Infantry Battalion, which was then used to make amphibious raids along the coast, harassing the enemy lines of supply. On 23 June 1944, the Fijians made one such raid on the Japanese roadhead of Mawaraka, but they ran into more opposition than expected and were forced to withdraw. During the move back to the barges, Suka, who was helping the wounded, was himself hit in the thigh and groin. Unable to move, he cried out to his comrades not to come for him, but he knew they would never leave him to the Japanese. So he raised himself on his hands, drawing a deadly machinegun burst that killed him but undoubtedly saved other men’s lives. The selfless Suka was awarded the British Commonwealth’s highest honour, the Victoria Cross, the first of three awarded for valour on Bougainville.3

The first Australian units arrived at Torokina in September 1944. They were part of II Australian Corps, which was to relieve XIV American Corps for service further afield. The Australian corps commander, Lieutenant General Stan Savige, had led the 3rd Division during the difficult Salamaua campaign. That division, now under Major General William Bridgeford and comprising the 7th, 15th and 29th Brigades, was part of Savige’s corps. Savige’s command also included the 11th and 23rd Brigades and the 2/8th Commando Squadron. Their main air support came from Royal New Zealand Air Force Corsair squadrons based at Torokina.4 At this stage there were still about 52,000 Japanese on Bougainville, significantly outnumbering the Australians.5

General Blamey thought it undesirable for the Australian troops to sit placidly within the Torokina perimeter, but Savige faced some constraints in taking the attack to the enemy.6 General MacArthur would not provide support for such operations; he was quite content for the Australians to do as his Americans had done. Savige had insufficient landing barges to support moves around the coast, and any land advance would be restricted by the need to build supply routes, including bridges.

In late November, troops from Lieutenant Colonel Geoff Matthews’ 9th Battalion, uncommitted at Milne Bay, but first into action here, moved northeast from Torokina up the Numa Numa Trail and came upon an enemy position at Arty Hill, halfway to the north coast. It was more than a year since the first American landings at Torokina, and this was the first major operation outside the perimeter. Matthews called it ‘a day of days.’ The attack went in on the morning of 29 November after 200 high-explosive and smoke rounds had informed the Japanese that the extended hiatus was over. The infantry cleared out the enemy bunkers, killing about twenty defenders, and held the position against strong counterattacks. Edwin Barges, a stretcher bearer, was the first Australian killed in the Bougainville campaign. There would be many more.7

On 30 December, Lieutenant Colonel John McKinna’s 25th Battalion attacked Pearl Ridge, the next feature beyond Arty Hill. McKinna expected to confront a company, but his troops came up against 550 men under Major General Kesao Najima, who were not only well entrenched but backed by artillery and mortar support. McKinna’s battalion took thirty-five casualties, ten of them killed, but the razorback ridge was taken. It was an important position: from the crest, the coastline of Bougainville could be seen on both sides. When Brigadier John Stevenson’s 11th Brigade took over, Savige ordered that there be no advance east of Pearl Ridge. Having secured the centre, the Australians would now advance north and south from Torokina.

The 31/51st Battalion led the push north along the coast towards the main Japanese defensive position, on Tsimba Ridge, in front of the Genga River. This 20-metre-high, 200-metre-long, semicircular ridge ended in a coastal cliff, and it would have to be taken in order to continue the advance north. On 23 January 1945, the Australian mountain guns opened proceedings, but the attack next day was unsuccessful. On 25 January, a flanking patrol reached and crossed the Genga. The rest of Captain Alwyn Shilton’s company followed and held the bridgehead against enemy counterattacks.

Waist-deep in water, Jack Horton and ‘Slim’ Anderson manned a Brengun pit within the bridgehead. In the pre-dawn darkness of 1 February, Anderson sensed an enemy presence and brought the Bren around to face it. Suddenly, slashing blows from a sword severed two fingers from his right hand and almost took another from his left. As he tried to defend himself, Anderson’s arm was broken and deeply gashed. Then he heard Horton shout, ‘Grenade, Slim!’ and the assailant was gone. Horton helped Anderson climb out of the pit, but now he faced the same menace alone. When the shadowy swordsman returned, the Bren gun misfired. Then Horton heard a bang and saw the muzzle flash of a pistol just in front of him. He jabbed the Bren into the midriff of his assailant, who fell forward into the flooded weapon pit. As the man surfaced, Horton crashed the Bren gun into his face and scrambled from the pit, but not before the sword swung again and caught him across the heel. A single rifle shot rang out: Cec Brooks had shot Naval Warrant Officer Tsunematsu in the head, ending the duel.8

The 31/51st had another go at Tsimba Ridge on 6 February. After a 40-minute artillery bombardment and air attacks by Corsairs and Wirraways, two platoons from Captain ‘Nick’ Harris’ company attacked at 0900. The men in Lieutenant Lionel Coulton’s platoon waded through a swamp up to their waists before advancing in line abreast up the timbered slope towards the ridge. The scrub kept them hidden until they had almost reached the first enemy positions. One of the Bren gunners, Alan Dunlop, turned twenty-five that day, but his thoughts were not on celebration. He had just had a ‘Dear John’ letter from his girl back home and was still churned up about it. He charged forward, firing his Bren from the hip: it was death or glory, and he didn’t care either way. Despair could be as deadly as any bullet. For Dunlop, the combination was fatal.9

When Bill Bunting, the platoon sergeant, copped a grenade blast in the back, Cec Cook tried to patch him up, but Bunting died in his arms. Cook then moved on across the ridge, now cleared of trees by the shelling, and jumped into a captured trench. The trench was about 2 metres deep and had a small bridge across the top under which Cook took shelter. Using his bayonet, he built a dirt wall across the trench. Later, one of Cook’s own men tossed in a grenade, thinking enemy troops had entered the trench. The dirt wall saved him.10

With Harris’ two other platoons also successfully attacking, the Japanese positions on Tsimba Ridge were untenable. On the night of 7 February, the defenders from Captain Kawakami’s III/81st Battalion company withdrew, leaving sixty-six corpses behind. Harris’ company had lost seven men killed and twenty-two wounded. Lieutenant Coulton had gone in with twenty-eight men, but only seven walked out. They all deserved a decoration, so the seven names were put in a hat and Colin Jorgensen was awarded a Military Medal.11

Bombardier Herbie Dhu was serving with the Second Mountain Battery, supporting the assault on Tsimba Ridge. Dhu and a number of his North Sydney Rugby League Club teammates had joined the unit back in 1943 and they had been sorely missed by the Bears in the grand final of that year. Three months later near Finschhafen that loss had been put into perspective when six gunners from the battery had been killed and seven wounded by an exploding shell as they sat down to dinner in the mess hut. Behind Tsimba Ridge Herbie Dhu finally earned his decoration, calling fire orders back to the guns and helping evacuate the casualties.12

General Savige was making his strongest push in the south, where Brigadier Raymond ‘Bull’ Monaghan’s 29th Brigade, the veterans of Salamaua, advanced towards Mosigetta. Troops of the 15th Battalion were taken down the coast by barge and seized the south bank of the Tavera River, while troops of the 47th and then the 42nd Battalion were landed even further south, gaining ground across the Hupai River. Savige, Bridgeford and many others of lesser rank were unimpressed by Monaghan’s bullish persona and poor control of his brigade. He was relieved and transferred a jungle warfare training role in Australia.

After his time fighting along the ridges around Salamaua, Peter Pinney had switched to the 2/8th Commando Squadron, commanded by another Salamaua veteran, Major Norm Winning. The unit had been in Bougainville since early November 1944 and was now operating as a screening force for the infantry. Captain Pat Dunshea, with two Military Crosses to his name from his actions at Wau and in the Ramu Valley, now led a commando troop under Winning. On 27 January, Dunshea and the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit officer, Captain Ray Watson, another Salamaua veteran, led a fourteen-man patrol out from Sovele Mission to attack a Japanese-occupied village. The patrol met up with Pinney and Daniel Fitzgerald, who had already scouted the village and learned that it consisted of a central cluster of huts and two outlying ones beside a garden area.13

Dunshea split his force in two, and the men were in position just before dusk. The Japanese troops were preparing their meal as Dunshea gave the signal to open fire; the first salvo followed by a shower of grenades at the village. Pinney wrote, ‘Cries of shock and pain as huts were riddled and Japs tumbled over in the blast . . . Under the hut there was a Jap still alive, but no chance of him surviving as a prisoner, so I put him out of his misery.’ After gathering all the documents they could find, the commandos left to spend the night away from the village. Next morning, two badly wounded Japanese soldiers were killed and the compound was burned to the ground.14

At this stage, about one-third of the available Japanese troops were engaged in gardening to feed the rest of the Army. Targeting the gardens would reduce the enemy’s food supply and divert more troops into guarding that supply. Pinney later wrote, ‘We all understood our role: keep up in the foothills behind the Jap lines, and raid down on the flats. Pinpoint his strongholds for our Corsairs and field guns—and ambush his roads and gardens. Shoot and shoot through.’15

The Owen gun was a good weapon for such tactics, but it could also be dangerous to handle. Like Pinney, Daniel Fitzgerald was an exceptional scout: as Pat Dunshea said, ‘You could send him anywhere on his own.’ On 2 April he was asleep on a groundsheet stretcher at Sovele. When he got up during the night, he accidentally stepped on the cocking lever of his Owen gun. The gun discharged and fired twenty to thirty rounds into Fitzgerald, killing him.16 In his honour, the commandos named the rough landing ground next to their Niheru base Fitzgerald Field.

At the end of January, Brigadier John Field’s 7th Brigade took over from the 29th and pressed inland towards Mosigetta and beyond. At this stage, the Japanese were only contesting the advance with ambushes; the battlefield itself was the greater threat. Troops here found themselves in the middle of deep swampland, trying to pick out a route from one narrow island to another. On 17 February, Mosigetta road junction was captured, and Field moved two battalions south towards the Puriata River. Field’s other battalion, the 25th, was landed on the coast near Toko and moved inland up the Puriata. This too was by no means easy going, with endless rain soon turning the Buin Road into a knee-deep wallow of mud. On 4 March, Captain Robert McInnes’s company from the 25th crossed the Puriata River; just over two weeks later, it attacked an enemy position astride the Buin Road. The war correspondent Arthur Mathers watched McInnes, ‘the Queensland youngster from Toowoomba whose three pips were inked faintly on his green clad shoulders,’ brief his men. Then eight RNZAF Corsairs came over and dropped daisy-cutter bombs on the enemy positions. As the last bomb crashed down, the artillery opened up. McInnes’s men moved back along the road to their former position, then took to the thick jungle on the right, reaching the jumping-off point as the last artillery round fell. As mortar fire came down, Lieutenant Ron Darlison’s platoon moved to the left with another platoon to the right in an extended line. ‘The mortars were still hammering the Japs as magazines and clips were thrust into Brens, Owens and rifles and grenades clipped on to belts,’ Mathers wrote. When the Vickers guns opened up, the men moved ahead. ‘Then,’ Mathers wrote, ‘came answering fire from all points of the compass.’17

Casualties mounted as the well-protected enemy machine guns found their range. Corporal Reg Rattey knew that if he moved his section forward the men would be cut down but thought he might be able to dash up on his own. While firing his Bren from the hip, he rushed the nearest bunker and threw a grenade inside. This proved effective, so he returned to get two more grenades before attacking the next bunker and an open weapon pit. Using his Bren and the two grenades, Rattey killed seven defenders and put the remainder to flight. Then, hearing a heavy Juki machine gun on the right flank, he moved towards it with his Bren, hitting the enemy gunner and dispersing the other defenders. While Rattey finished with the Juki, Ken Forrester and Ian Cooper chased the fleeing crew through the jungle to a nearby creek, shooting down three of them. Arthur Mathers watched from a perch to the rear as ‘grim silent men with the sweat and blood of battle upon them sought out any lurking Japs.’18 For his valour, Reg Rattey was awarded the Victoria Cross.

Preliminary attacks, captured documents and prisoner interrogations all gave indications that the Japanese were planning a significant offensive in the south in early April. Lieutenant Joe Chesterton was in command at Slater’s Knoll, the forwardmost Australian position south of the Puriata River. After a series of Japanese attacks on 30 March, only beaten off with the help of Matilda tanks from 2/4th Armoured Regiment, Chesterton’s men had done much to strengthen the defences. They cut back the scrub in front of the perimeter and replaced it with barbed wire and cleared interlocking fire lanes for the Vickers guns. Three killing grounds were prepared in this way, to the north, northwest and southeast of the perimeter.19

An hour before dawn on 5 April, wave after wave of Japanese troops attacked the 129 men on Slater’s Knoll. The Japanese had surrounded the position during the night, but the attack was launched prematurely after one of the Australians spied an enemy soldier in the pre-dawn gloom and alerted his comrades with a warning shot. The main line of attack was from the southeast, through a patch of thinned out jungle between the road and a low, bare ridge. Three Bren guns had been positioned here for enfilading fire to complement a Vickers gun and an anti-tank gun firing from the front. Dawn revealed the enemy dead piled up in heaps at the double-apron wire barrier.20

Lieutenant Syd Giles and Sergeant Ted Lloyd, two of the eleven men who went out to check the perimeter, were shot dead by a waiting sniper. The Japanese toll was much higher. A total of 292 bodies, including that of Lieutenant Colonel Takatsugu Kawano, who had commanded the attack, were buried in three mass graves, but that was only about half of the death toll. An estimated 620 enemy troops had been killed and even more wounded from about 2400 men in the two infantry regiments used in the abortive attack.21 If the odds were indeed 18 to 1 against the Australians, it speaks volumes for the relative tactical nous of the opposing forces.

In mid-April, Brigadier ‘Tack’ Hammer’s 15th Brigade took over from Field’s 7th. After waiting in vain for weeks for the Japanese to make another sacrificial attack, Hammer continued the advance southeast. The objective was the Hongorai River and then the Hari. Led by Matilda tanks, the 24th Battalion moved east along the Buin Road, with flanking units patrolling to the north. After crossing the Hongorai, they had a rough fight for Egan’s Ridge before the 58/59th Battalion took over the advance to the Hari River. Here the Japanese were well dug in on the east bank. As he had done at Salamaua, Hammer pushed the 58/59th hard. Three company commanders were wounded within days of each other, Captain Cedric Baumann mortally so. On 9 June, General Blamey cautioned, ‘Take your time, Hammer, there’s no hurry.’22

Blamey’s comment reflected the general view of the Bougainville campaign. Many of the men, and many Australians back home, thought it a futile exercise. Though a number of the former militia battalions on Bougainville were now designated as AIF, with over 75 per cent of their troops volunteering for service elsewhere, these men would continue to serve, and be killed, only on Australian territory.

Peter Pinney knew how to kill. On 2 June, he waited beside a track with the rest of a commando patrol near Mobiai, watching several groups of enemy soldiers moving back and forth. When a bunch of twenty marines came along, the ambush was sprung. The lead man went down almost instantly under the hail of fire. ‘With my first man riddled,’ Pinney wrote, ‘I gave the rest of the mag to the bloke just behind him.’ But the enemy response was swift. ‘These Nips were no pikers,’ Pinney noted. ‘They were so good they were firing back within four seconds . . . I let a second mag rip . . . Chick [Parsons] got two white-hatted officers and as a Nip was crawling away he riddled him from arse to Adam’s apple with his Bren.’ However, after Alan Cobb thumped down on the butt of his Owen gun and accidentally shot himself, Pinney’s officer hastily pulled the men out. ‘I raced off like a hare, zigzagging,’ Pinney wrote. ‘Emptied the rest of the mag at khaki movement, from behind a second tree—and then blew in earnest. It was scary . . . my legs wouldn’t run fast enough, and I was flat to the boards.’23

Improvised explosive devices were part of the Japanese delaying tactics along the Buin Road. The 58/59th found more than 100 mines and booby traps in just three days. The men of Lieutenant Bill Woodward’s 7th Bomb Disposal Platoon were kept busy clearing the way for the tanks by walking in front of them and prodding the ground with a bayonet. In the first ten days of June, they took care of some 200 ‘mines’—most of them improvised by rigging a detonator to a cluster of artillery shells.24 Further north, a streamlined 57/60th Battalion pushed eastward through uncharted territory and reached the Mobiai River on 23 June, unhinging the enemy’s defence of the Buin Road.

The 29th Brigade—now under Brigadier Noel Simpson, who had shown such fine command qualities at Finschhafen and in the Middle East—took over from Hammer’s 15th. But even a fine soldier like Simpson was hard pressed to deal with the relentless rain, which soon reduced the Buin Road to a sea of mud. Communication links failed in the wet, and even the carrier pigeons wouldn’t fly. The Australian engineers worked the hardest at such times: now they built a road of sorts between Torokina and the Mivo River that included thirty bridges. By August, as the end of the war approached, both sides were preparing for a major battle at the western approaches to Buin.25

Despite having about 12,000 men in the Buin area, the Japanese on Bougainville were unable to deploy more than about 20 per cent of their strength into the forward areas. At any one time, around 30 per cent of troops were out of action owing to sickness, 35 per cent were assigned to gardening, and 15 per cent were on transport duties.26

North of Torokina, the Australians continued to make some deep patrols. Lieutenant Frank ‘Blue’ Reiter, a platoon commander with the 31/51st Battalion, had been awarded a Military Medal on Crete when, he said it had been ‘on for young and old.’ On 27 March, his patrol attacked an enemy camp at dawn, killing six Japanese and setting several huts ablaze. Instead of scarpering, the canny and easy-going Reiter had his men stay put and wait for the camp to return to normalcy. Just after midday, they struck again, killing another two men and torching more huts. Only then did they return to base.27

Still further north, the Australians had moved forward from the Genga River positions captured in February. By mid-May, the 26th Battalion had cleared the Soraken Peninsula and the 55/53rd Battalion had pushed up as far as Ruri Bay on the east coast. The remaining Japanese troops in the north pulled back to the Bonis Peninsula, holding strong positions across its base. On 3 June, the 31/51st, conquerors of Tsimba Ridge, took over positions on the west-coast flank. Patrols along the front line were proving costly, and it was clear that any attack would need to be well planned. It was decided to make an amphibious landing at Porton Plantation, further up the west coast and behind the enemy’s line across the neck of the peninsula. Once the landing had been made, the main ground attack would go in from the south.

Captain Henry ‘Clyde’ Downs’ company would make the landing, reinforced by engineer, mortar and machinegun detachments, 190 men in all. The force, carried in six landing craft, travelled up the west coast and headed in to the landing beach before dawn on 8 June. The three armoured landing craft of the first wave reached the coral reef 50 metres offshore, and the men waded ashore unopposed. Three more landing craft, which were unarmoured, grounded 75 metres offshore and their infantrymen also waded in. However, enemy machinegun fire soon broke out, preventing the unloading of the heavy weapons and stranding on the reef the two landing craft that carried the mortars and reserve ammunition.

Confined to a small perimeter on the beach, the infantry held on, supported by artillery fire directed by Lieutenant David Spark. Patrols sent out to find and eliminate the enemy machinegun positions came under heavy fire, which steadily increased as enemy reinforcements moved up. Facing about 300 defenders and with the mortars and reserve ammunition still on the stranded barges, Downs’ men were in trouble. A convoy of five landing craft tried to go in that night but all were stymied by the low tide and enemy fire.28

The only option now was to extract Downs’ men. So far, casualties had been relatively light: four men killed and seven wounded. But on this second day, as Downs gradually pulled in his perimeter, the attacks were coming in waves. ‘We are now near the beach and getting hell,’ Downs radioed, asking that the evacuation take place as soon as possible after dusk. Spark brought down artillery fire within 25 metres of the contracted Australian perimeter, while the Corsairs bombed the old perimeter positions.29 At 1630, the first three armoured landing craft beached 50 metres from shore, and the walking wounded and stretcher cases were taken on board under heavy fire. One of the wounded recalled that, ‘It was just a chattering blast firing from every possible direction.’ The infantry followed, protected by Downs’ rearguard and a Vickers gun crew. As the last men dashed for the barges, the Vickers stopped firing, and the gunner removed the locks and threw them into the sea.30

However, the three landing craft had come in too far, and the weight of the men held them fast on the coral reef. They tried to push the barges off but it was no easy task. The one in the centre swung wildly around on the coral and began to sink, settling on the reef with its stern pierced. Downs ordered the men back on board, where the twin Vickers guns gave covering fire until the enemy’s fire had killed two gunners and rendered the guns inoperable. Twenty men on that landing craft then swam to another barge waiting about 200 metres further out.31

Back on the central landing craft, the water went on rising inside the pierced hull and soon stopped the engine and flooded the radio. Ken Ward, who had distinguished himself onshore fighting off enemy attacks on the perimeter, exposed himself to fire and tried to pick up a smoke canister with his bare hands. When it proved too hot, he used his bayonet to cut away the burning stores it had landed on. The Corsairs continued their air support until dusk, allowing the northernmost craft, with sixty men on board, to get off the reef. The men on the other two stranded craft faced the night.32

Using poles, the twenty-six men in one of these barges managed to push it off the reef on the rising tide, despite drawing considerable fire once the engines started up. But the final landing craft, with Downs and sixty other men on board, remained hard aground and half full of water. About twenty wounded men were now lying in the water at the bottom of the boat, and some had to have their heads held above the waterline to avoid drowning. Downs ordered the remainder to remove their boots so they wouldn’t tread on the wounded. Some enemy troops waded out from shore to throw grenades, but the Australians saw their heads above the surface in the moonlight and sent them on their way. At about 2300, Downs told the men they were free to take their chances ashore and try to reach the Australian lines.33

At least five men left their weapons and ammunition and went over the side. They made their way to the supply barge that had stranded during the initial landing and there met up with Lieutenant Joe Patterson. The group found two life buoys and used the tide to float out into the darkness of the bay, drifting south while the supply barge went up in flames behind them. The buoys helped to support the three men who could not swim. After a while, the group was joined by the native guide who had helped bring the first wave of landing barges to Porton. At about 0630 the next morning, they reached the shallow water of Torokori Island, 2 kilometres north of Soraken Peninsula, and went ashore; they were later rescued by artillery observers. Everard Glare had swum all the way with a non-swimmer in tow. 34

At dawn on 10 June, there were thirty-eight men left alive on the stranded landing craft. Downs had disappeared during the night and was never seen again. Corporal Eric Hall took charge and issued all the remaining rations. Water was a big concern, and the wounded were given the juice from the tinned fruit. Hall tried to make more room on the boat and even issued lengths of copper pipe so the men would be able to breathe when the tide rose. An air attack was made on the enemy positions, and rubber rafts were dropped adjacent to the craft. Under cover of smoke, another landing craft then tried to get through, but after several of the crew were wounded and the steering gear was hit, it had to withdraw. Hall tried to knock out the most troublesome enemy bunker with his Bren and even splashed shots in the water in a line towards the target to guide the supporting aircraft in.35

That night, with the exhausted men almost spent, a Japanese soldier clambered onto the stern of the barge from a native canoe and opened fire with a LMG, killing two Australians and wounding several others. Then an anti-tank gun opened up from the shore. Two shells tore the stern off the stricken vessel before Australian artillery quietened the gun. Around midnight, two landing craft got within 150 metres, and three assault boats, each with two sappers from the 16th Field Company aboard, headed in under the artillery fire. Smoke and dust from the shelling made it difficult to find the stranded craft, but the first assault boat managed to rescue five men, though two of its crew, Lieutenant Arthur Graham and Maurie Draper, were wounded in the process. The second rescue boat managed to get seven men off, and the others were rescued before dawn.36

Two Cairns men, ‘Hec’ Bradford and Les Bak, both part of a patrol from the Porton perimeter, made it through to the Australian lines near Ratsua on the afternoon of 10 June, and another two came in the next day. The patrol commander, Lieutenant Noel Smith, and his batman, Ernest Duck, were never seen again.37 The Porton operation had been an absolute shambles, leaving twenty-three men killed or missing and 106 wounded. General Blamey watched the disaster unfold from near Ratsua on the afternoon of 9 June, and some of the men involved wondered if the operation had been organised for his benefit.38

Brigadier Arnold Potts’ 23rd Brigade had initially been deployed to secure the outer islands. It was Potts’ first front-line command since the Kokoda campaign, and Savige had to put a leash on him immediately. In mid-June 1945, one of Potts’ battalions, the 8th, took over the front line on the western side of the Bonis Peninsula neck. As the Japanese had shown by their response to the Porton landing, they saw holding this position as vital. They had about 1200 troops on the peninsula and another 1400 on Buka Island, to the north.39

On 24 July, Major Charles Thompson’s company sent two platoons to attack Base 5, at the southern end of the Bonis Peninsula. Henry Banks, who had served with the 8th Battalion at Darwin before the move to Bougainville, was a section commander in Thompson’s company. Lieutenant Charlie ‘Squizzy’ Taylor’s platoon would lead the assault, with Banks’ section, down to only five men, in the centre. The Australians’ initial line of approach crossed three enemy bunkers hidden under a big log; fire from one hit Taylor in the knee. The stretcher bearers strapped a rifle to his leg as a splint and got him out.40

The main enemy positions were along the ridge. Banks noted that ‘we knew where they were but getting at them was another thing . . . They were dug in there under banana palms.’ As Banks’ section moved up onto the ridge—really just a stretch of higher ground—the Bren gunner, ‘Freddie’ Wade, was killed by a single shot. This was the signal for a machine gun to open up, and Bill Kearney, the forward scout, was ‘almost cut in half ’, though he would survive. The intensity of the fire cleared the ridge. ‘When I stood up,’ Banks recalled later, ‘there was nothing there. They just cut all the vegetation down in front of where my section was . . . They were savage.’41

Banks could see where the firing was coming from: a log-roofed pit covered with earth and vegetation. He threw one grenade at it, and Bill Ings handed him another. Then the No. 2 man on the Bren gun, who had been attached to the section for this attack, came up. He was Frank Partridge, a well-read young farmer from the north coast of New South Wales. ‘I’m going in, Corp,’ he told Banks. As Partridge moved up to the bunker, an Australian grenade exploded on top of it, badly wounding him. ‘You goon, Troedson,’ he roared at the thrower, ‘Bert’ Troedson. Despite his wounds, Partridge threw his own grenade into the rear of the bunker and then went in himself. Two of the defenders were down, and when a third challenged him, Partridge used the cut-down bayonet he carried to finish him off. Banks now came up to the bunker, put an Owen burst into the two Japanese soldiers lying inside, and helped Partridge out. ‘He was too weak to go anywhere, he had lost that much blood,’ Banks recalled.42 Partridge was awarded a Victoria Cross, though he did not learn about it until he returned to Australia.

The Australians also took over the American lodgements on West New Britain. Since the defeat of the Japanese counterattacks at Arawe and Cape Gloucester, the Japanese command had concentrated its main forces at the eastern end of New Britain, defending Rabaul. The first units of Brigadier Raymond Sandover’s 6th Brigade, part of Major General Alan Ramsay’s 5th Division, landed at Cape Hoskins on 8 October 1944. Sandover’s brigade comprised the 14/32nd, 19th and 36th Battalions. The experienced 36th had served at Sanananda, and patrols from this battalion were also landed further east, along the north coast. After a number of clashes between Australian and Japanese patrols, the 14/32nd landed at Jacquinot Bay on the south coast of New Britain on 4 November. By February 1945, the Australian units had leapfrogged along the north and south coast to Open Bay and Wide Bay respectively. Between the two bays, the island’s width narrows to about 35 kilometres, and it was here that the two forces joined up.

Tol Plantation was captured in mid-March, and the remains of the men who had been murdered three years earlier were found. Their deaths provided some of the impetus for further Australian operations against the Japanese. In early April, Brigadier Eric McKenzie’s 13th Brigade relieved the 6th, and by May an airfield had been constructed at Jacquinot Bay for two squadrons of RNZAF Corsairs. With the equivalent of five Japanese divisions now isolated in Rabaul, ground action was restricted to fighting enemy patrols as the Australians played the waiting game.