CHAPTER 4

Your Brain Is Listening

What subject did you like the least at school? Math? French? Geography? In my case, it was chemistry.

Imagine you have this class from 8:00 until 9:00 a.m. What do you say to yourself before walking into the classroom? How do you picture the next hour? “This will suck!” Did you arrive early? Unlikely. We usually show up at the last minute to things we don’t enjoy. The class hasn’t started yet, but you’re already thinking that it will be long and boring. We’re all the same. Were you more distracted? Did you look at the clock every five minutes? Under these circumstances, we’re less likely to learn or get much pleasure from discovering something new. As anticipated, the class feels like it’s dragging, and this subject certainly won’t be our favorite. Typically, your lowest grades on your report card were from these kinds of classes.

Which subjects did you like the most? History? Drama? French? You’re probably expecting me to say gym class. In fact, my favorite subject was math. Like me, you’re probably less inclined to drag your feet when you walk into your favorite class. Before class starts, we’re telling ourselves that it will be interesting, and we even show up a little early. We learn better, have more fun, and get higher grades.

The point I want to make is that the class itself has almost no impact on our performance. Instead, it’s our attitude towards it that determines whether we’ll pay attention or not.

Our thoughts significantly influence our behavior.

I was always fascinated by my friends who would show up to chemistry class excited, full of curiosity, and ready to learn. We went to the same class, had the same teacher, and were taught the same subject matter. But the way I perceived chemistry dictated the rest. If I had adopted a different outlook, the result would have been different. For example, I could have told myself, “Okay, so it’s not my favorite subject, but I’m going to make an effort to sit at the front of the class to pay closer attention, then I’m going to stop saying that the teacher is boring. I’ll see how it goes.” I can’t say that chemistry would have suddenly become my favorite subject, or that my final grade would have jumped 20 percent, but modifying my attitude would have triggered a series of smaller, more constructive changes. Whether we like it or not, we end up building our reality based on the thoughts we have.

What does your self-talk sound like at work?

- What’s your frame of mind in the morning? “Man, it’s going to be a long day today” or “My busy day will go well. One step at a time.”

- How do you prepare for a meeting with your boss? “I don’t like him!” or “Focus on the importance of the meeting, and things will be better.”

- What message is your inner chatter sending to your brain before a presentation? “I’m not going to be good enough this morning” or “I know my stuff. I’ll be great.”

Be careful because your brain hears everything you say, even if you don’t say it out loud.

See both sides of the coin

The performers I coach live in all sorts of situations, some more complex than others. Sometimes, my job is to challenge them to look in a different way at the situation that’s bothering them. In other words, to help them see the other side of the coin.

An Olympian once said to me, “If I blow it at the Games, I’ll be letting down thirty-six million Canadians.” Not all Canadians follow the Olympic Games, but I understood his viewpoint. It’s one way of seeing things. So, I encouraged him to look at it from another angle. I’m fully aware that the thought of letting people down is a very powerful, scary feeling and, as such, it carries real weight. From the start, when the athlete is deeply rooted in the negative emotion, it’s extremely difficult to look at a situation from another point of view. I love having these conversations. We explore options together until the original thought has faded just enough to allow other perspectives to emerge. These conversations can be difficult and heavy at times because of the strong emotions involved.

In this case, we came up with something like, “If I perform the way that I prepared, my country will be proud of me. Results aren’t everything.” Now, that’s much better.

I never blame the athlete for their initial thought. The sole purpose of the exercise is to help the Olympian understand that their self-talk can either limit or help them. It’s a choice.

Many clients have told me that when they face a problematic situation, they now ask themselves, “How would JF challenge me to look at this scenario?” I prefer being the little angel, not the devil, on their shoulder!

When we change the way we look at things, the things we look at change.

We’re creatures of habit. The thoughts we have about a situation that we experience over and over again rarely change. A psychology professor told me that 95 percent of the thoughts of people who experience routine day-to-day activities are more or less the same from one day to the next. Scary, isn’t it? Basically, once we’ve decided to look at a situation in a certain way, we rarely think of questioning it.

For example, consider the FedEx logo. It’s a sign that you’ve seen again and again. When you look at it, you probably see the letters F-e-d-E-x. What if I were to say to you that you could also see something else? Look at the space between the E and the x. You’ll see an arrow pointing to the right.

Ever since someone pointed this out to me, I always see the arrow first. This logo proves that we end up seeing what we’re looking for.

How many times do you look at a situation in the same way? Are some of your thoughts limiting the way you perceive things without you realizing it?

Just as a coin has two sides, there’s always another way to see any situation.

Enough with the catastrophic thinking!

In the course of my career, I’ve worked with people representing more than forty different nationalities. Over time, I noticed certain cultural differences in the way people perceived the same reality.

As a proud Canuck, I am happy to say that Canadians are some of the most open, nice, welcoming, hard-working, and fun-loving people. However, I’ve also noticed that Canadians tend to exaggerate and dramatize events. Complaining and whining are popular pastimes. For instance, some of us feel sorry for ourselves as winter approaches because we can’t accept the reality of colder weather coming our way, as if winter wasn’t supposed to show up this year! We don’t accept the situation and end up working against it instead of with it.

The act of complaining is like rocking back and forth in a comfortable chair. It offers temporary comfort, but it doesn’t get you anywhere!

The tendency to dramatize often occurs during the most stressful moments. We quickly jump to conclusions and become impulsive and reactive.

For example, let’s take a hockey player who makes a mistake. He causes a giveaway that leads to an opposing goal. The coach calls the player back to the bench and . . . boom! Wild thoughts begin to race through his mind:

- “Why’d I do that?”

- “Bye-bye, ice time!”

- “Well, no more power-play shifts for me.”

- “I’m such a loser.”

- “I’ll never get drafted.”

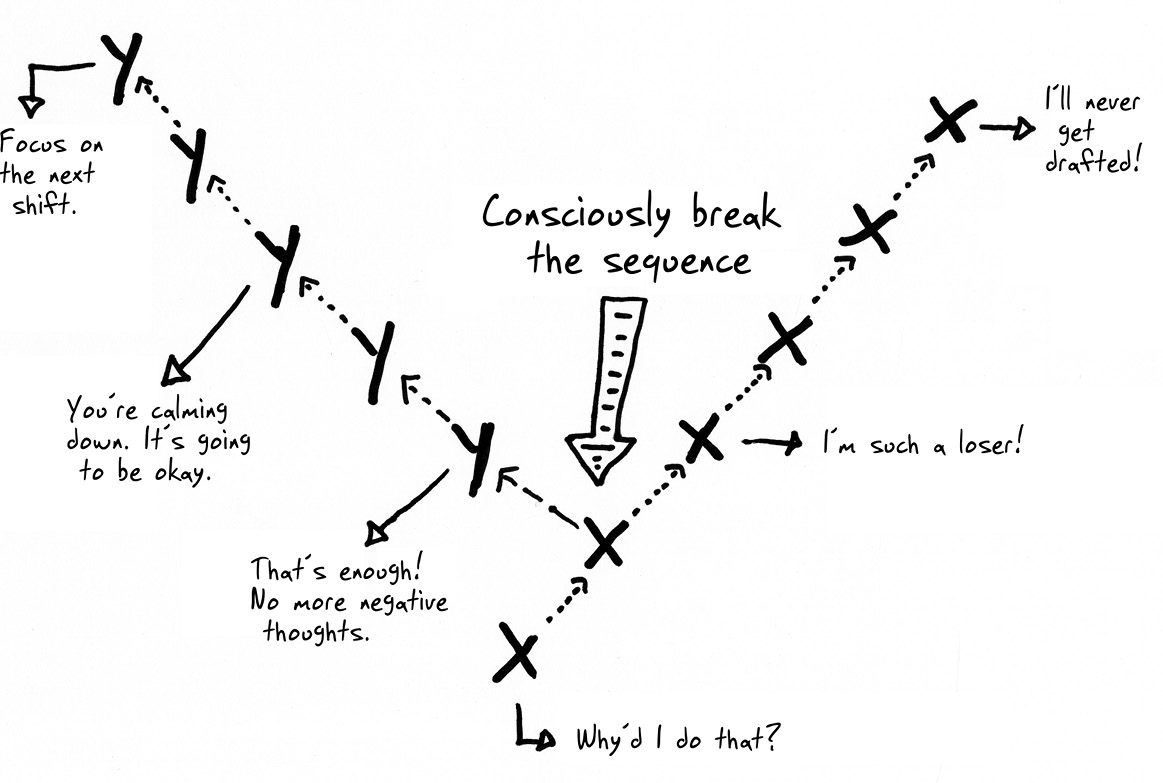

These catastrophic thoughts take no more than a few seconds to go from “Why’d I do that?” to “I’ll never get drafted.”

We know, logically, that the mistake wasn’t all that important. But in a situation in which we’re under pressure, catastrophic thoughts have free rein because we’re in a vulnerable state. The problem isn’t that we made a mistake; everyone makes mistakes. The real issue is the way we perceive our mistake.

The hockey player should, instead, be aware of the risk of spiralling out of control if he lets his disastrous thinking overwhelm him. Allowing this thought pattern to happen only deepens his anxiety and the negativism. Being self-critical isn’t a problem per se, as reflecting back on what happened leads to finding solutions. But we’ll come back to this a little later.

This hockey player needs to interrupt the illogical sequence of disastrous thoughts that end up being completely detached from reality. “Whoa, I’m digging myself into a hole. That’s enough. Back to reality.” The inner chatter must be reset to get back to helpful thinking.

By simply breaking the sequence of negative thinking, we can redirect ourselves and reach a calmer state of mind in a matter of seconds, as shown in the following diagram. Choosing path y over path x yields a significantly different outcome.

In the end, it isn’t the problem that is the problem. The real problem is your attitude toward the problem!

Be aware

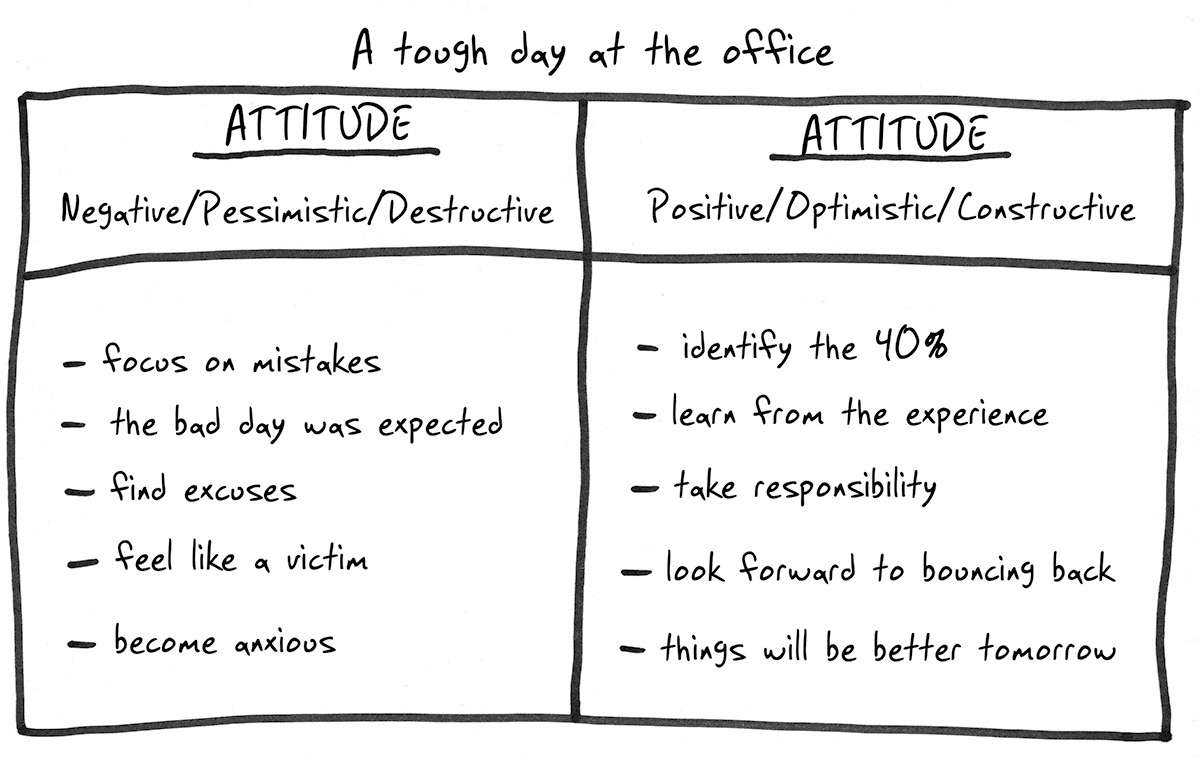

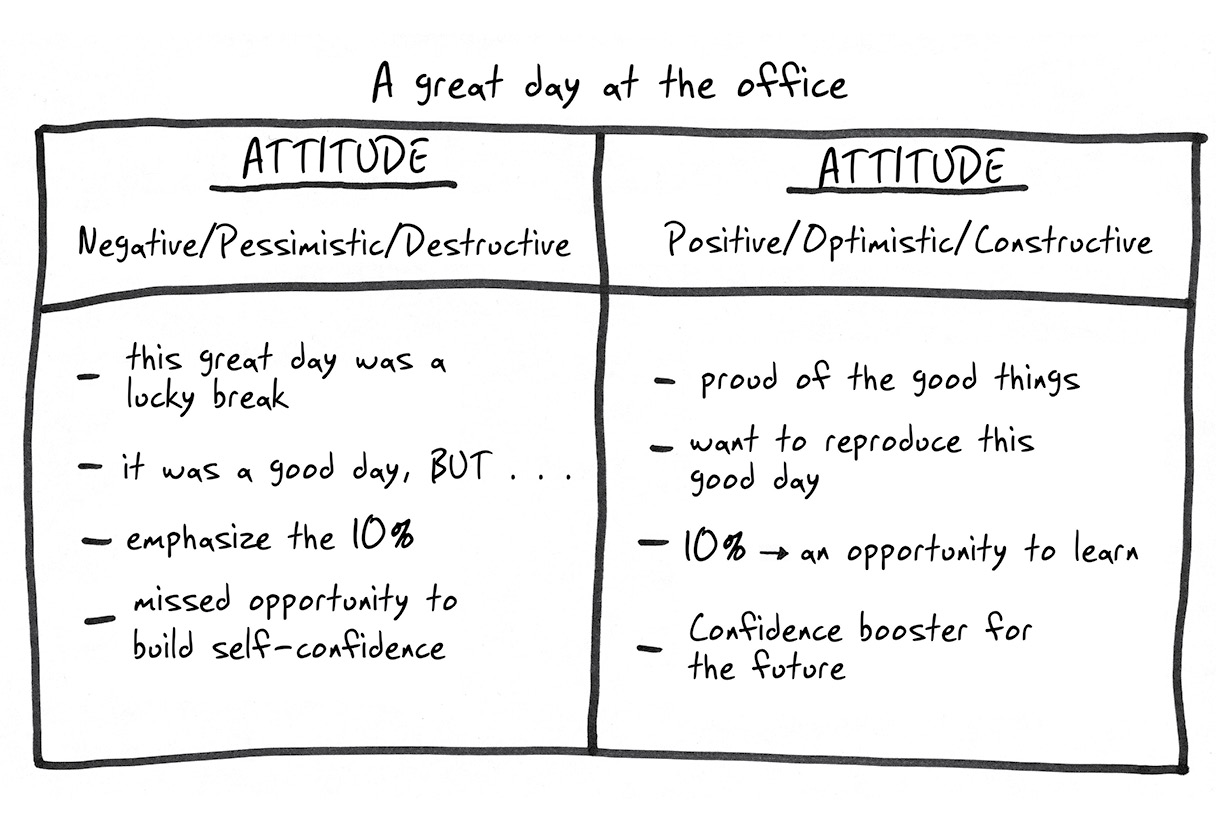

Below is an exercise that I use during mental coaching sessions to show the impact that our attitude can have on a situation. There are two scenarios:

Scenario A: You just had a tough day at work. You feel that the meetings you attended weren’t very effective, you couldn’t stay focused, and you made a few dumb mistakes. About 60 percent of your day was bad.

Scenario B: You just had a great day. You felt productive, focused, and confident. You feel that you dealt with a lot of work effectively. You were on fire and rate your day as 90 percent successful.

Let’s analyze these two scenarios from two different angles: a negative/pessimistic/destructive mindset and a positive/optimistic/constructive mindset.

Let’s consider Scenario A (tough day) through the negative/pessimistic/destructive lens. It’s no surprise that you’re focused on the bad things that happened during the day. You tell yourself that your bad day unfolded as expected. You dramatize the consequences of your mistakes and find excuses to explain the bad day. You see yourself as a victim, put yourself down, and decide that tomorrow won’t be any better. This sequence of negative thoughts can make you fearful, anxious, and highly uncertain about the future.

On the flip side, how would you see the tough day if you used a positive/optimistic/constructive attitude? You would try to counterbalance it by focusing on what you did well, even if this represents no more than 40 percent of your day. You would draw lessons from the things that didn’t go so well. The poorly executed tasks cannot be excused; they would become useful information to help you bounce back quickly. You would take responsibility for the situation without putting yourself down. You would see this as a one-off situation and say to yourself that things will be better the next day.

Now, let’s consider Scenario B, having a great day, through the negative/pessimistic/destructive lens. You don’t believe that you’re the reason behind your own success. “I was lucky!” You see this great day as being the exception, not the rule. Typically, you’ll acknowledge that it was a good day, but . . . “Yes, it was a good performance, but I missed the shot, but I got a penalty, but the opposing team scored when I was on the ice.” When you use “yes, but. . .” you only emphasize the words that follow but, whether it’s a mistake, a fault, or a tiny slip-up. You discard everything that comes before yes. It’s much better to use “yes . . . and . . .” to recognize what also precedes the word and, which typically refers to what went right. In the end, it’s a missed opportunity to build self-confidence thanks to all the small wins earned during the day.

Choosing to see the situation with a positive/optimistic/constructive mindset is very different. You’re able to acknowledge and congratulate yourself for the small victories. You go over what made your day so great to be able to reproduce it in the future. As for the 10 percent that didn’t go well, you take it with a grain of salt while still noting the opportunities to learn and improve.

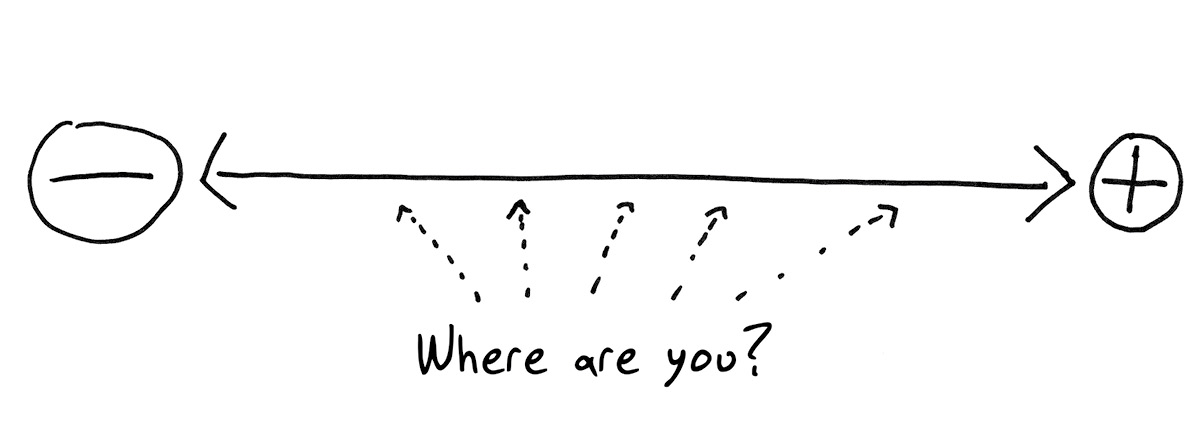

You may not be an extreme pessimist or optimist, but you’re certainly somewhere on the spectrum between the two.

Through which lens do you feel you view your life? Are you influenced more by one or the other? Do stressful moments affect your attitude? Do you tend to switch lenses based on who you’re with?

In the end, no matter what kind of day you’re having, only you can turn it into a learning experience. The lens you choose will color how you perceive your reality.

Do I always need to be positive?

Positive psychology first appeared in 1998. It was the dawn of the new millennium, and modern psychology was changing along with the times. Since then, multiple books have been published on this topic, not least of which are those by Dr. Martin Seligman, who is considered the father of positive psychology. He’s published more than 250 scientific articles and twenty books, most of them bestsellers that have been translated into more than twenty languages.

Why has positive psychology suddenly become so popular?

There’s a desperate need. We live in a world of international disputes, terrorist attacks, climate change, global pandemics, social injustice, collusion, fake news, hate messages, manipulation, and harmful working conditions. Beautiful and desirable things are trafficked all over social media, manipulating us, whether or not we want to be. We feel envious when we look at our friends’ ten vacation snapshots of a tropical paradise, #bestvacationever. Is that real life? Is the grass really greener on the other side? When we compare, many of us end up thinking that our lives are pretty awful. Under these circumstances, it’s easy to see why books on positive psychology have gained so much traction.

Of course, having a positive attitude isn’t the miracle cure for a world of negativism. Being a “cheerleader” doesn’t protect us from feeling miserable, since reality is much more complicated than that. When I coach my clients, I make sure they understand that there’s a difference between having a positive attitude and having the right attitude.

Imagine that you have a twelve-hour workday ahead of you, filled with meetings and ongoing projects. At four in the afternoon, you feel tired and need a jolt, but you have to work until seven. You want to persevere, so you choose the right attitude and say to yourself, “I’m going to focus on the next task and forget about the rest for now. I’ll make it. I’ve done a lot more compared to what’s left.” This self-talk is constructive, supportive, and practical.

Here’s another example. You made every effort to deliver a report on time. Your boss reads it and suddenly you find yourself at the receiving end of a tongue-lashing: “This file is not to our standards!” Your boss decides that you’ve spent enough time on it and that the project will never see the light of day. Under these circumstances, would the right attitude be to say, “That’s okay. It’s not the end of the world. There’ll be other projects”?

No way. The feelings of frustration and anger, justified under the circumstances, would be suppressed, denied, and swept under the rug. The right attitude here is to acknowledge the disappointment and process the criticism of having underperformed.

I recall some Olympian clients who were angry because they had underperformed but were able to move on, in contrast to many of their rivals. Sure, they criticize themselves, but not for long. Great champions have this ability to avoid getting bogged down in catastrophic thinking and quickly regain a constructive attitude.

Taking the time to cushion the blow isn’t negative in itself; emotions must be expressed. They also reflect a deep desire to succeed.

Georges St-Pierre, aka GSP, learned this the hard way. He’s recognized as one of the best mixed martial artists to ever step into the octagon. During his fifteen-year professional career, he successfully defended the UFC welterweight title nine times while putting up an overall record of twenty-six wins and two losses.

A few years ago, I heard GSP speak at a leadership event, and one anecdote he shared really caught my attention.

On April 7, 2007, GSP was the favorite to win against American Matt “The Terror” Serra to defend his title for the first time. He thought the win would come easy, but to his surprise, the fight turned out to be a bitter lesson in humility. He performed poorly and lost badly. Embarrassed and humiliated, GSP vowed to do everything he could from that moment on to avoid feeling these unpleasant emotions ever again. He chose to make several changes to his training regimen, and they worked. He used this devastating loss as motivation to get better and stronger than ever. GSP retired twelve years later, unbeaten since his heartbreaking fight against the Terror.

His negative experience led to a positive one.

Contrasts can help

I’ve noticed in my coaching that we learn a lot from contrasts. We savor successful moments more after experiencing a few failures. In the same way, we enjoy good times after having experienced setbacks and adversity. We realize how important our health is after we’ve been sick. We appreciate the summer because we froze all winter. Cubans don’t appreciate warm weather like we Canadians do because they have it year-round!

As we saw in GSP’s story, both positive and negative experiences offer opportunities to learn. The experiential contrasts force us to reflect, to weigh the pros and cons, and to make better choices for the future.

In our everyday lives, we spontaneously use the words positive and negative a lot to describe someone’s attitude. For example, “She has a positive attitude,” or “He’s so negative!” Limiting ourselves to these two adjectives can oversimplify a point of view. I challenge my clients to use more specific words, to better describe mindsets.

- A constructive or a destructive attitude: will my way of thinking build or destroy my relationship with my colleague?

- Solution-based or problem-based thinking: will my strategy solve the problem or make it worse?

- A helping or a harmful attitude: will my inner chatter help me or hurt me before I begin this difficult discussion?

- An attitude that propels or holds back: will my constant self-criticism generate or limit new ideas?

- A winning or a losing attitude: will I come out of this interview having won or lost?

Finding a variety of words helps us understand our mindsets more accurately, thus elevating our thinking beyond simply contrasting positive and negative.

Clearly, the point here isn’t just to be positive, but rather to choose the right attitude. The attitude that will best help you handle a situation correctly and make you learn some important lessons whether the conditions are good or bad.

What does it mean to be mentally tough?

Over time, the expression mental toughness has become a part of popular culture. I’ve coached many people throughout the years who I would consider tough mentally: Olympians, of course, but also surgeons, soldiers, actors, musicians, and corporate leaders.

Being mentally tough means choosing the right attitude even when a situation defies you.

It’s easy to have the right attitude when everything is going well. It just happens naturally. But having the right attitude when things aren’t going as planned, that requires mental toughness! When an athlete won’t give up despite things going badly, we hear commentators say that they are gritty, tenacious, and relentless. That’s exactly what I’m talking about.

When I was starting out as a mental coach, I prepared a teenager for the year’s most important track and field meet. The weather conditions weren’t great: cold, rainy, and windy. Most of the competitors never stopped complaining. “This blows! This really sucks!” Tough as nails, the young athlete saw the situation differently.

He had packed the necessary clothing in his bag to withstand the cold. Check. As for the rain, he knew it wasn’t going to slow him down because the Weather Network forecast wet conditions during the qualifiers, but only clouds for the final. Check.

“No stress,” he said.

“And the wind?” I asked.

He told me that he had reached out to the organizers the night before to find out which direction he would be running in. “I’ll have the wind at my back. I think I’m going to beat my personal best today!” he said. Check.

He had chosen the right attitude and ended up clocking a personal best time.

A muscular brain

Developing mental toughness is like building muscle strength. To strengthen a muscle, we train it by increasing the weight, the resistance, and the number of repetitions. The same goes for our brains. Our mental strength increases when we decide to face up to the challenges that take us out of our comfort zones. The more we train ourselves to choose the right attitude at difficult moments, the tougher and more resilient we become in the face of adversity.

Through purposeful mental training, our mind can deal with even more complex situations like muscles that can handle heavier loads. It can get to a point where some situations that flustered us in the past will seem insignificant in hindsight.

Remember the clown in Chapter 1? When it was time to pick spectators in the audience to come up on the stage, he deliberately chose those who seemed reluctant. At each show, he intentionally challenged himself to sharpen his skills, which was his way to avoid getting stuck in a rut and to progress as an artist. He knew how to train his brain.

I would like to share a personal story. As a teenager, I was a rather shy adolescent who often lacked self-confidence when it came to tougher challenges. Sometimes, I had a bad habit of throwing in the towel before I had even tried to tackle the challenge. I preferred the easy route and was often a sore loser. (I still am, but I experience it way differently!) As a child, my parents would let me win at board games to avoid having to deal with my fits. When I tell this story to the people who know me today, they have a hard time imagining JF acting that way.

I remember avoiding situations that made me feel vulnerable. Being a perfectionist, I didn’t want to risk failing and looking bad in front of others. It was only when I attended university that I realized that I had a lot to gain by changing my impeding attitude. So I decided to attack my weaknesses, and by weaknesses I mean the fear of speaking in public, the need to dodge sensitive discussions, and the intense dislike for being criticized.

I admit it, at the time I was mentally weak.

I rarely chose the right attitude in tough situations. I was more inclined to find excuses to explain my mistakes and to run away from moments of vulnerability. Luckily, some professors at university saw greater potential in me. Through them, I understood that I was limiting my personal growth because of my disruptive perfectionist mindset.

Thanks to their advice and the performance psychology training, I was able to look at things from another angle. I began to willingly put myself in situations that pushed my limits. I tamed the discomfort of feeling vulnerable. Little by little, I set goals that were bold. In the end, I succeeded in breaking free, and I say break free because I really felt imprisoned by my former mindset.

I was the shy JF; now I’m a sought-after speaker. I was the JF who avoided sensitive topics; I now have fierce conversations with clients every day. I was the JF who hated criticism; I now ask clients to provide honest feedback about my work. I feel that I’ve transitioned from being mentally weak to being mentally tough. I’m proud of the changes I’ve made, and I now get to coach people in the same direction.

Essentially, all we can do is embrace the challenges and choose the right attitude.

Everything starts between the ears

While working on new acrobatic tricks, one of the Cirque du Soleil trapeze artists would say, “I’m always one thought away from doing it right.” He was right. A single thought can change our performance. The right thought can lead to an exceptional performance, while negative inner chatter can lead to failure.

- I won’t be able to do it.

- I won’t be at my best.

- They won’t like me.

- It won’t be as good as the last time.

Do you have these kinds of thoughts? Do you recognize them in someone you know?

Everything starts between the ears. It’s like the electrical panel in our homes. The wiring carries electricity to the power outlets, appliances, and light fixtures throughout the house. In the case of humans, the panel is our brain. The brain sends orders through the nervous system to the different body parts to do what’s needed to perform.

Let’s look at the following image to explain the impact of inner chatter on our behavior. There are three aspects to performance: psychological, emotional, and physical.

The psychological aspect refers to what we think (our thoughts), the emotional aspect represents what we feel (our emotions), and the physical aspect is what we do (our behaviors).

The psychological sphere is placed at the top, since everything stems from it. The thoughts we choose every day build our reality. These thoughts will have a direct impact on our emotions, while our emotions will influence our behaviors, which, in turn, will affect our thoughts. For better or for worse, it’s a never-ending, self-conditioning cycle.

For example, if you feel panicky because you’re about to speak to a large audience, ask yourself how you perceive the situation. If your inner chatter sounds like this, “Everyone is looking at me. If I say something wrong, they’ll judge me,” the nervousness will produce cortisol, the human stress hormone. Your body will tense up, your voice will rise, and your speech will accelerate. In this state, you could lose your train of thought or, even worse, draw a blank during your speech. On the other hand, if your thoughts are a little more constructive, such as, “I will take my time and speak slowly and clearly. Things will be fine,” the nervousness won’t go away completely, but you’ll feel more in control emotionally and behaviorally.

Ultimately, bringing extra attention to the way you perceive situations can increase self-awareness, which, in turn, will enable you to better control your feelings and actions.

Figure out your brain

When people overthink, we use the expression “get out of your head” so that they don’t overanalyze and get lost in their thoughts. This is especially true when someone is caught up in a destructive spiral, such as useless speculation. To gain more control, we must take the time to understand how our brains work to generate the thoughts we want and eliminate the others.

We can’t change a behavior if we don’t understand what triggered it.

Think of the triple bubble diagram in the previous section. The first letter of each component — Psychological, Emotional, and Physical — spells pep, as in the pep talk a coach might use to get their team hyped up for a game.

Too much importance is given to pep talks. These speeches are sometimes useful, other times not at all. If an athlete counts on their coach’s pep talk to get revved up for the game, they’re relying on an extrinsic source for motivation, something which is out of their control. This could be dangerous because if the coach’s pep talk isn’t bang on, it could do the opposite and demotivate or confuse the athletes. Similarly, a worker may rely on their boss’s speech, but, as we know, not all bosses have what it takes to motivate their employees.

How often are traditional pep talks useful? Do they really get you going? Is a “rah-rah” cheerleading approach what you really need?

The best pep talk, in my opinion, is the one we give ourselves. Only we know exactly what gets us going, and only we understand what message we need to hear to trigger the right emotions. Nobody understands our brains better than we do. Plus, we have full control of our inner chatter.

The only relationship that lasts forever is the one we have with ourselves. We are the person we talk to the most! All other relationships, as satisfying as they may be, are temporary. So it’s critical that we get along with ourselves. We need to become our own best coach.

I encourage you to come up with your own best pep talks, like an Olympian!

The brain believes what it hears

Have you ever embellished an anecdote a little to make it more interesting and thought-provoking? You know, the type of “augmented reality” story we tell our friends after work on a Friday while having a cold, refreshing beverage. Yes? Well, you’re not the only one!

“Hey! I bumped into the Toronto Raptors coach at the airport this week. We chatted about the team’s success for at least five minutes. He’s a great guy.”

But the real version would go something more like this: “Hey! I crossed paths with the Toronto Raptors coach at the airport this week. I shook his hand and wished him good luck.”

When we tell the exaggerated version the first time, we make sure that we mention the little embellishments correctly. We want to captivate our listeners’ attention while making sure the story is credible. It’s a little easier to tell the anecdote the second time, but not as easy as the tenth time. Sharing the story repeatedly makes the embellished version sound true. We start believing our own lie!

Comedians are the best at doing this. Most of their stories are inspired by facts, but they spice them up to entertain the crowd. To make the stories believable, they rehearse them many times over before telling them to an audience. Their storytelling abilities are so good that they make something fabricated sound real.

Why do we believe our own exaggerated stories?

For two reasons. First, because of the influential details we add to the story, and second, because of the multiple repetitions. Many of us do this constantly in our daily lives without even being conscious of it.

For example, you may say, “Nothing is going according to plan.” Is this entirely true? Probably not. Some things may not be going as planned, but everything? Isn’t this a little overdramatic?

“I’m such a loser. I can’t do anything right.” Really? Can anyone truly say that they fail at everything, all the time? Definitely not.

“My boss said that I am hurting the business.” In fact, the boss was expecting more leadership within the department. These are two very different messages.

I could go on and on.

A problem arises when we repeatedly tell ourselves these same kinds of twisted statements, not just once or twice. Our brains are listening to our distorted story, repeated over and over again. Your mind believes your story just like your friend believed your anecdote about running into the Raptors coach at the airport.

The brain doesn’t really distinguish between what’s real and what’s imagined. It simply believes what it hears, not what’s true.

Pay particular attention to your inner chatter. By doing so, you’ll increasingly notice the link between your thoughts and your emotions. The brain is always listening. What you tell yourself repeatedly will influence the rest. It’s up to you.

The benefits of having the right attitude

We hear parents, teachers, sports coaches, and bosses say how important it is to have the right attitude. Well, we should listen to them because there are important benefits to developing the right attitude. Let’s explore some of these benefits — without exaggerating or twisting the examples, of course!

Laughing and smiling make us feel good

It’s no secret that we face an endless number of stressful situations in our lives, such as challenges at work, family issues, gloomy international news, climate change, and more. Within this social noise, having some ways to deal with the struggles of everyday life is essential. As simple as they may seem, smiling and laughing are powerful antidotes to tougher times. We tend to forget it, but they are anti-stressors that we can use as much as we want, whenever we want.

People who have a great attitude are inclined to smile and laugh naturally. I would even say that these natural mechanisms are directly linked to maintaining the right attitude. If you have pessimistic tendencies, try to smile and laugh more often. You’ll soon notice the benefits.

Below are the advantages that smiling and laughing bring:

- The body produces endorphins, the feel-good hormones. Think about how you feel after a big belly laugh.

- Laughing provides additional oxygen that spreads quickly throughout the body and the brain and relaxes the nervous system.

- Laughing is a great workout! The diaphragm expels air from our lungs at speeds over sixty miles per hour, which increases blood flow and reduces arterial pressure.

- When we smile, several tiny facial muscles contract in a specific sequence. This sends positive messages to our brains that “Things are good!” which, in turn, contribute to a sense of well-being.

- Smiling and laughing are contagious. They foster positive relationships within a group. How can we resist smiling back when a baby smiles at us, right? We respond spontaneously to a smile.

If you can’t make yourself laugh enough, you can join a laughing group. In 1995, Dr. Madan Kataria founded workshops in which people go through a series of voluntary laughing exercises. The workshops are based on the belief that voluntary laughter boasts similar physical and mental benefits as real, spontaneous laughter. This practice is commonly used to help people deal with depression and other mental illnesses. Given its effectiveness, it instantly went viral! There are now laughing clubs in every major city in the world. Curious about this practice, I enrolled in a few workshops; I loved it so much that I went through the training to become an instructor.

Did you know that children laugh approximately six times more than adults do in a day? As we age, we tend to take life too seriously and end up laughing less and less. Isn’t that sad?

When I’m standing next to athletes dealing with high-pressure moments, I make a conscious effort to show a positive attitude. I’ll subtly crack a smile at strategic moments to create a more relaxed atmosphere.

World champion boxer Marie-Ève Dicaire is a pro at using this strategy. Her joyous attitude and ear-to-ear smile helps her stay relaxed. Whether she’s three days or three minutes away from fight time, the smile is there. Did her signature smile help her win that world title? Hard to say, but one thing’s for sure: that smile puts her in an ideal frame of mind.

A few years back, I traveled for the first time with an athlete to a Grand Slam event in Europe. At the competition venue, I noticed that the funny and sarcastic person I knew during our sessions in my office had changed to a serious and cold individual. I knew him well enough to understand that this behavior was due to unnecessary self-imposed pressure.

During his warm-up, I asked him to show me his teeth. He understood that he hadn’t smiled all day. He suddenly burst out laughing! Naturally, he relaxed, and ended up competing very well.

Sometimes, the best way to deal with adversity is to just laugh it off.

As the old saying goes, don’t take life too seriously, as nobody gets out alive anyway!

Become a go-getter

The person who maintains a great working attitude will be better equipped to persevere in the face of adversity. They tend to dive in more and overcome obstacles more easily. When they get knocked down, they get up quickly and find the courage to come back stronger. Bouncing back from failure is considered a win. This mentality feeds the ego and reinforces the determination to push even further.

I will always remember a young gymnast who had auditioned for Cirque du Soleil. On paper, her acrobatic skill level was much lower than that of the other candidates auditioning for the same position. But this young woman never saw them as a threat. Instead, she kept her eyes on the prize and never wavered. “One day I will be a Cirque du Soleil artist,” she told me. She struggled with some of the tough acrobatic and artistic training, which caused her to cry on multiple occasions. But she never gave up. Her tears were nothing more than a way to release her emotions. She saw this challenging audition as a way to build character, which would serve as a solid foundation for her future career.

During the audition, she kept progressing, slowly but surely, thanks to her go-getter attitude. A few months later, she earned a well-deserved contract to join the legendary show Saltimbanco.

Fast-forward two years, and she’d become one of the best artists in the show and one of the most appreciated by her peers. The casting department who recruited her for the audition were stunned by her progress. I wasn’t. The go-getter attitude makes it possible to achieve great things and sometimes reach unsuspected levels of excellence.

What type of glasses are you wearing?

Having the right attitude makes it easier to push through barriers. Athletes with great mindsets can see beyond obstacles to stay focused on reaching their goals.

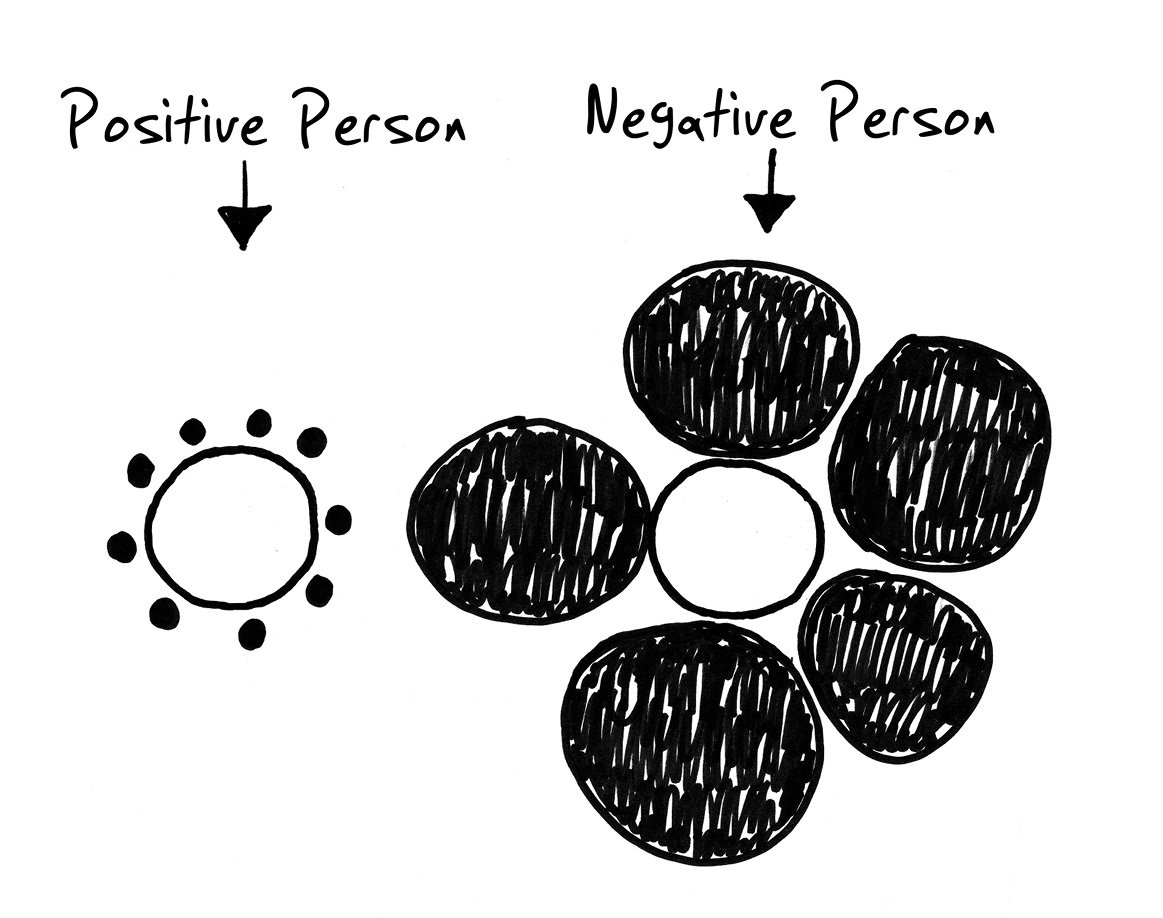

Our reality is constructed from how we perceive things. Everything depends on the type of glasses we’re wearing, and how they color what we see. Take a look at the following diagram.

So, let’s say that the circle on the left represents the positive person, and the one on the right, the negative person. As you can see, the two circles are the same diameter. Now, look at the black circles in the next drawing. Imagine that they represent distractions that could prevent someone from succeeding, such as added pressure and tough challenges.

The negative person tends to exaggerate difficult situations, to see them as bigger than they really are, which explains why the circles on the right are larger.

This individual is surrounded by large, self-imposed black circles that are difficult to manage. Under these circumstances, it’s hard to focus on anything other than the cumbersome problems that block the light at the end of the tunnel. Discouragement isn’t far away.

Now, let’s look at the circle on the left. The positive person also has their share of obstacles, but they assign far less importance to them. They choose to see the impediments as they are. The optimist recognizes the black circles yet sees them as situations they can resolve and overcome. They don’t let the distractions take over, no matter how many there are.

Look at the two white circles. Do they still appear identical? The one to the left seems bigger, doesn’t it?

A hockey goalie I work with says he feels bigger when he has the right attitude. “I take up more space in the net. I cover the angles so much better.” On the other hand, when his inner chatter is negative, he feels smaller and lost in his net.

One of my clients is the president of a big company in Montreal. He’s an eternal optimist and an impressive problem-solver. During one session, we were chatting about his current situation at work, and I asked him if he saw the glass half empty or half full. His answer caught me by surprise. “JF, my glass is always full — one half is water, and the other half is air.” Such a typical answer from that guy!

Let’s finish off this section with one of my all-time favorite quotes from former British prime minister Winston Churchill: “The pessimist sees difficulty in every opportunity. The optimist sees the opportunity in every difficulty.”

Take out the negative!

Our minds are programmed to think in the simplest way possible. They respond well to commands and affirmations, but not to negative words because those cloud the message. For example, if you tell your brain not to think about failure, it’s baffling because the brain gets confused with sentences containing negative words. But if you tell it to think about succeeding, it understands perfectly.

We must tell our brains what we want, not what we don’t want.

Take a grocery list, for example. You write down what you want to buy. When you enter the grocery store, you head for the items on your list, even if you have hundreds of other items in front of your eyes. You’re an efficient shopper. But what if you were to write things on your list that you don’t need, such as “don’t buy yogurt, flour, and juice.” Unthinkable, right? And these would probably be the first items that catch your eye as you go up and down the aisles, even if you don’t need them.

Words such as “not” or “don’t” indicate what we want to avoid, which becomes a non-linear way to deliver a message to our brain. We typically use negative wording during stressful moments, when we must make a quick decision, leaving the brain no time to understand the meaning of the message. For example, in the middle of a bout, a boxer knows that they have to keep their guard up. Their message would be more effective if they were to think “Keep your hands up” as opposed to “Don’t lower your hands.”

There are two reasons for this.

First, when things are happening quickly, the brain is trying to pick up information as quickly as possible. It will only pay attention to the most important words, such as “lower” and “hands.” The message received is, in fact, the opposite of what is desired.

Second, the brain will have to analyze the message twice to get the correct meaning. “You’re asking me not to lower my hands. Therefore, you want me to keep them up.” Then, bong! You get your bell rung with a left hook.

You’ve probably written a multiple-choice exam at some point in your life. Have you ever noticed how questions full of negative words are much harder to understand? Try this.

Which countries are not European? Choose the best answer.

a) Canada, Australia, and Argentina

b) France, Italy, and Switzerland

c) Japan, the United States, and Peru

d) Spain, Portugal, and Austria

e) a and b, but not c

f) a and c, but not d

g) a, c and f

The answer is g. Did you have to read the question and the answers a few times to understand? So confusing, right?

I took a wellness class at university that was supposed to be a walk in the park. Most of the students were doing very well heading into the midterm exam, so no one was worried. Well, as it turned out, the multiple-choice questions were full of negative words. The class average was a “brilliant” 64 percent. A few of us complained that the midterm wasn’t written properly, and fortunately, the professor wrote the final exam differently. The average mark for that test was 84 percent.

Imagine your golfing partner saying, “Don’t hit the ball into the bushes!” or your work colleague telling you as you’re about to give your presentation, “Did you know that the big boss is here? No big deal, just don’t screw up!” Not exactly what you want to hear just before an important performance.

Limit the negative words and get straight to the point.

Reduce anxiety

A pessimistic attitude can generate anxiety. When stuck in this mindset, we spend a lot of time and energy thinking about what could frighten us, harm us, or possibly threaten us. However, fear isn’t an emotion that should be completely eliminated, as it can sometimes help us identify a risk and adjust to it. Yet when we let fear hold us back, it becomes a hindrance. Too much anxiety can become overwhelming.

Each time you see the negative side of a situation, it’s like adding a drop of water to a glass. At some point that glass starts to fill up and get heavier. When a pessimist finds a way to look at reality a bit more optimistically, they typically feel relieved and lighter — there is less weighing down their glass.

Furthermore, if you held a glass of water with a straight arm, the glass would feel light, right? But if you hold it for several minutes, the same glass begins to feel so much heavier. The same applies with anxious thoughts that weigh on us.

Just let go!

An optimistic attitude leads to thoughts that make us feel good, happy, and calm. Do you remember the skill of celebrating small wins in Chapter 3? It’s an excellent way to reinforce your positive attitude. Below are a few examples:

- Think about the good things you did during the day.

- Think about the things you are thankful for.

- Think about future projects that excite you.

- Remember the times you were happy.

Just thinking about these small wins will put you in a good mood.

When I played squash competitively, my coach was seventy years old but didn’t look a day over forty-five. He had played professionally in England, so when he picked up a racket for a game, watch out! Beyond his impeccable coaching skills, it was his outlook on life that made him exceptional. “If we’re so good at creating our own misery, we can be just as good at creating our own happiness,” he would say. It’s a choice.

Often, we let our frame of mind as soon as we wake up in the morning have a serious impact — whether good or bad — on our whole day.

- “I didn’t really sleep well. It’s going to be a long day at the office.”

- “It’s a big day at school today. At least we’re starting something new. I find that really motivating.”

- “We’re launching our new product on the market today. I’m a little nervous, but it’s an exciting moment. I’m proud of what I accomplished.”

“Did you get up on the wrong side of the bed this morning?” This popular expression refers to someone who is in a bad mood. Someone chooses to be in a bad mood; it doesn’t happen on its own.

On what side of the bed do you usually get up? Pay attention to your inner chatter when you start your day. Most elite athletes start their day with positive affirmations. Try it. It will brighten your day!

Caution, it’s contagious!

We mentioned that smiling and laughing exude contagious positive energy. The same applies to negative energy. Who likes to be around people who are always negative? Their bad aura affects our morale and saps our energy. Did you ever notice how the atmosphere starts to quickly deteriorate when someone negative joins a group of fun and lively people? If you’ve played team sports, you may remember the bad apples on your team. I’ve noticed that the negative experiences in our lives affect us more than positive experiences do. This principle is called negativity bias. No wonder we have to put a little more effort into keeping our thoughts positive.

After my early-morning workouts at the gym, I spend a good fifteen minutes in the sauna to relax, unwind, and self-reflect. As a matter of fact, a lot of content in this book stemmed from ideas that came to me in the sauna!

From time to time, a sixty-year-old man uses the sauna while I’m there. I’ve never heard him say anything positive. He’s a first-class grouch who’s always negative. He refuses to be responsible for anything that happens to him and constantly blames others for his misfortunes. I purposefully close my eyes when he walks in so that he doesn’t talk to me. Pessimism is contagious just like the flu, so I stay away!

Now, think of people who are positive. They attract other people, right? We appreciate their presence and are drawn to them because of their good mood.

Let’s put this to the test. At work, you need to recruit a new member for your team, and you’re pressed for time. In desperation, someone shows you photos of the following three candidates. Quickly: which one would you choose?

When I do this experiment during my talks, almost every participant chooses number three. I ask them why. They tell me that this candidate seems to be

- nice,

- a good work colleague,

- happy,

- intelligent; and

- professional.

I imagine that many of you chose the same person for similar reasons. The photos show three very different types of body language. The choice is easy, yet, after only a few seconds, we’re ready to welcome this individual to our team without knowing anything more about their professional career. Just a quick glance is enough to say that they would be an asset, just as the body language of candidates one and two convinced us of the opposite.

We must bear in mind that we, too, are being judged every time we walk into a room. People will draw conclusions about us, whether they’re right or wrong, based on what we project physically. Whether it’s when we attend a meeting, are on a first date, or are getting home after work, our body language speaks volumes without us realizing the impact it can have.

When I played junior hockey, something happened during a playoff game that still haunts me to this day. We were comfortably ahead by two goals when the other team managed to tie the game before the end of the second period. We felt the momentum suddenly switch. In the dressing room between the second and third periods, I delivered a short speech to calm the boys down and avoid any sort of panic setting in. As team captain, I told the guys that we had to go back out there and fire on all cylinders! I felt that my pep talk had worked. As we were getting ready to leave the dressing room, our coach walked in, concern written all over his face. He gave an incoherent speech that was delivered so nervously that we felt completely deflated. We lost our mojo, the game, then the series. I always wondered how much the coach’s behavior influenced the game’s outcome.

Human beings are social beings, just as much at work as during a hockey game. We find ourselves in groups all the time, so it’s normal to be influenced by the energy of our peers. We just need to be aware of this social influence and, when we can, choose situations that are beneficial for us. If this isn’t possible, then put a shield on so that you’re not consumed by the negative influences around you to the detriment of your own positivism.

I was the mental performance coach for five athletes during the Rio Olympics. One of them was Canadian decathlete Damian Warner. The decathlon consists of ten events over two days: three throwing events, three jumping events, and four running events. Athletes earn points based on results for each event, and the one who accumulates the most points is crowned champion. Decathletes are rarely perfect in all ten events. There are at least a few unexpected hiccups, so it’s common to ride an emotional roller coaster over the course of the competition.

To support Damian, the other coaches and I agreed to display a positive attitude no matter what happened. We promised each other that we would stay confident and unshakeable when Damian experienced moments of doubt. The moment would certainly come, we just didn’t know when. Even if Damian had learned stress management techniques, we knew he was counting on us for additional support. Heading into the Olympic Games, we knew that beating the great American champion Ashton Eaton was a long shot. Not impossible, but unlikely.

Fast-forward to day two. The first eight events had gone reasonably well, but far below Damian’s own expectations. Not only was the gold medal beyond his reach, but he also had to give up the silver because of Frenchman Kevin Mayer’s impressive performance. As Damian was getting ready for the ninth event, he had to accept that he was now fighting for bronze against Germany’s Kai Kazmirek.

This was the moment we were prepared and waiting for.

The ninth event is the javelin throw. The athlete is allowed three attempts to throw the javelin as far as possible. Kazmirek’s best throw out of three attempts was 64.6 meters (70 yards), a personal best. Damian, for his part, couldn’t throw farther than 58 and 56 meters (61 and 63 yards) on his first two attempts. His back was against the wall. He needed a much better throw on his final attempt to collect valuable points and reduce the gap separating him from the German before the final event, the 1,500-meter run. At that point, Kazmirek was sitting comfortably in third place in the overall standings.

I was in the stadium, sitting in the front row with the other coaches, roughly 150 feet from Damian. He still had some time to get ready for his last javelin throw. I was watching him as he was sitting there, nervously, shoulders bent forward, with a long face and worry in his eyes. His posture didn’t bode well for this decisive moment.

With a few minutes to go, he looked in our direction, acknowledged our presence, and walked over. We showed him our enthusiasm through encouraging gestures and big smiles, and shared a few last-minute technical cues. Suddenly, he realized that he wasn’t alone. His face lit up, and he smiled back at us with that same grin that we knew so well.

His body language completely changed.

Damian approached his final attempt much more confidently. He threw the javelin with authority, and it finally pinned the ground at 63.2 meters (69 yards), his best throw all season! Damian ended the decathlon beautifully with a great 1,500-metre run to finish with 8,666 points, enough to beat the German and capture his first Olympic medal.

Damian did mention afterwards how important that moment was. Our positivity was contagious enough to help him change his inner chatter from “I’m worried” to “I know I can do it.”

Let’s put this into practice. I would like to share with you an exercise I like to call “Energy Givers and Energy Takers.” The goal is to identify all the situations, people, tasks, and environments that energize you followed by the ones that drain your energy.

Once you’ve completed the first step, you then come up with practical strategies that will maximize the things that generate energy and minimize the things that don’t. I use the verb minimize because only in a perfect world could we ever eliminate all the energy takers from our daily lives.

This exercise is especially useful to protect your valuable energy throughout your workday.

Here’s an example based on the responses of a corporate client.

|

Energy Takers |

Minimize? |

Energy Givers |

Maximize? |

|

My boss |

• better organized for shorter meetings • come in with the right attitude |

Eighties music |

• listen to music when doing paperwork |

|

Sitting at my desk for long periods of time |

• walk for five min. every hour |

My colleague Michael |

• pop into his office regularly • have lunch together |

|

---- ---- ---- |

---- ---- ---- |

---- ---- ---- |

---- ---- ---- |

Let’s start by looking at two examples of situations that drained this client’s energy levels.

“My boss is moody and intimidating. I always feel apprehensive about our weekly meeting. I never want to go.”

This client knew he had to give himself the means to handle this situation better. So, he decided to send his boss an agenda ahead of time so that the discussions would be structured and more efficient. By doing this, he hoped that it would shorten the meetings. He also wanted to change his frame of mind. Instead of showing up feeling completely vulnerable, only he could improve the situation by adopting a better attitude and refusing to give her all this power over him.

He also realized that staying glued to his chair all day was affecting his mood and impeding his performance. To fix this, he decided to program a timer to go off every hour. He would then get up and walk for five minutes to stretch his legs. He knew that he would be more efficient after moving for a few minutes.

Now, over to the energy givers.

“I love listening to music from the eighties. This music brings back nice memories that make me feel good,” he told me.

We decided that he should connect his ear buds when he had to get through tasks that weigh him down, like paperwork.

“I really like Michael. He’s ambitious, energetic, and funny.”

He made it a habit to drop by Michael’s office once in a while and invite him to lunch more often to chitchat about his current projects.

You, too, can find simple ways to reduce the impact of the takers while using the givers better to maximize your energy levels every day.

Have the right attitude

As a mental coach, I’m often asked which mental skill is the most important. Without a doubt, the answer is having the right attitude.

Olympians travel around the world to take part in different international competitions. They live out of their suitcases. Before they leave, I often ask them if they’ve packed the one thing that they can’t leave behind. After they’ve rhymed off clothes, equipment, a pillow, and all the usual things, they no longer know what to tell me. I tell them, “Make sure you’ve packed the right attitude. Everything else is secondary.”

The brain is a powerful tool that can help or harm you, and you’re fully responsible for showing it the way. Healthy and positive thoughts, even if they don’t come spontaneously, will end up conditioning the mind.

Nothing is good or bad; it’s only your thinking that makes it so.

In closing, here’s an interesting fact about the word attitude that you may have already seen on your social media feeds.

First, let’s assign a percentage in sequence to each of the letters of the alphabet, starting with 1 percent. For example, A = 1, B = 2, . . . Z = 26. Next, let’s add the percentages for each of the letters in the word A T T I T U D E:

a + t + t + i + t + u + d + e

1 + 20 + 20 + 9 + 20 + 21 + 4 + 5

=

100

Not 77, not 113, but 100 percent! Is this a coincidence? Of course! But does it make sense? Absolutely!