CHAPTER 6

Develop an Olympian Calm

I feel like I was born to be a mental performance coach. Nothing makes me happier than to help athletes achieve their full potential. Over the years, I’ve helped athletes win the Super Bowl, conquer the X-Games, become world champion, and make it to the Cirque du Soleil stage. These achievements were all special, but nothing beats witnessing an athlete winning gold at the Olympic Games. Is it because they only come around every four years? Maybe. Is it because of patriotism, your country against the rest of the world? Could be. Whatever the reason, I hold the Olympic Games dear to my heart.

There are steps that an athlete must take before even thinking about winning Olympic gold. They first have to perform successfully at international competitions — World Cups and Grand Slams — and then climb onto the podium at major events, like the Pan American Games and World Championships. Similarly, an employee has to climb up the hierarchy to reach the C-suite.

When I first started working with Olympians in 2013, I had the privilege of coaching a few athletes who had already performed well on the international stage. The first major sporting event that I attended was the Commonwealth Games in Glasgow, Scotland, in 2014. The athletes I was working with during these games podiumed, so it was mission accomplished.

My second date with major games was the Pan American Games in Toronto in 2015. I was there to coach a female wrestler who ended up dominating her opponents and capturing her first Pan Am gold medal. When she stepped on top of the podium, I was suddenly struck by the following thought: “Don’t get too excited, my man. Sure, the athletes did well at the Commonwealth and the Pan Am Games, but next year is what really matters.” The 2016 Rio Olympic Games were less than a year away.

That thought really hit home. I felt a mixture of fear, panic, and self-doubt. I also felt guilty for not having enjoyed the moment when the wrestler was being crowned Pan Am champion. Sitting in the stands, I was beginning to feel the pressure of the Olympic Games, even though they were still many months away. I didn’t want to disappoint anyone. The athletes, the coaches, the Olympic Committee, and B2ten (an organization that hired me to work with some of Canada’s top Olympians). Heck, I didn’t want to disappoint myself as well!

Usually, I’m confident in my own abilities, but that evening in Toronto, I had my doubts. I experienced an overwhelming feeling that I wasn’t ready for the Olympic adventure. Not to my perfectionist standards, anyways. I hated this apprehensive feeling; however, it forced me to find some answers and seek help.

When I got back home, I shared my experience with my family and closest friends. I realized that I had to become more disciplined and modify a few things in my own life. My job is to challenge athletes to get out of their comfort zone, so it dawned on me: “What about you, JF? What are you currently doing to be the best version of yourself? If the Games were held next month, would you be ready?” The answer was a resounding no. That’s when the following mantra came to me:

If you want to work with high performers,

you need to be a high performer yourself!

I decided to get on with my mission. To my credit, I was already fit and ate healthily. I was probably tapping into 85 percent of my potential. Not bad, right? But I wanted to raise it to 95 percent.

As a result, I made four changes to my life:

- I forced myself to get the beauty sleep that I needed, regularly. I took a disciplined approach to make sleeping well at night a priority.

- I exercised more intelligently to stimulate my metabolism. I designed a program that incorporated a series of short but intense workouts. I followed my regimen religiously, five to six times a week. My body reacted extremely well to this new training program.

- My third challenge was changing my eating habits: smaller portion sizes, less sugar, more nuts, and less alcohol, prioritizing fresh vegetables over fruits and becoming an avid snacker to avoid hunger rages. The results were immediate. Combined with my new training regimen, I shed fifteen pounds in eight weeks. I felt amazing. When my mom first saw me after, she said, “Are you sick? You’re so skinny. You need to eat more!” Oh, mother!

- Last, I decided to manage stress better. I made an effort to eliminate many energy suckers in my life. I also meditated more. This would help free me from the small, daily stressors.

I made these changes so that my life would make more SENS: Sleep, Exercise, Nutrition, and Stress (as in stress management). It was far from being a fixer-upper, as these habits were already a part of my life. Instead, I just made sure to implement them better.

Thanks to the small tweaks, I felt an extraordinary sense of well-being, so much so that I’ve been religiously following this routine since 2015.

As they say, small changes can have big results.

Final preparations before Rio 2016

My sixth sense was telling me that, despite my personal improvements, I was still missing something. I took my mission seriously and really wanted to succeed. As a perfectionist, I wanted to do everything I could to face the biggest challenge of my professional career.

Of the five athletes I was coaching, three had been to the Olympics already. Given that I’d never been to the big dance, I kind of felt like an impostor working with these experienced athletes. It became clear: I had to learn more about the Olympic Games. After all, I was preparing athletes for this event, wasn’t I?

But where could I find what I was searching for? It’s not like there are university programs that teach how to get ready for the Olympic Games. I decided to go straight to the source. I reached out for help and managed to speak to a bunch of people who had firsthand experience in the Games.

Between September 2015 and February 2016, I interviewed twelve people: retired athletes, coaches, mental performance coaches, sport therapists, administrative support staff, and high-performance directors. I asked them to tell me, in detail, about their Olympic experiences.

They were extremely generous. Thanks to their help, I was able to put together a thirty-five-page, Olympic-sized document that I read over and over again. Here are a few important nuggets:

- You will be extremely busy, working long hours with few breaks. Take care of yourself.

- The schedule will change every day. Be prepared to adjust to any surprises, as there will be many.

- On-site, security is everywhere. As a result, it will take longer than planned to move from point A to point B. Plan your travels so that you won’t have to rush.

- It will be an emotional roller coaster. Some athletes will succeed, others will fail. Expect to experience some great moments of joy and disappointment.

- The people around you will be tired and stressed out; they’ll need you.

- From time to time, you’ll need to get away from the frenzy of the Games to unwind. Get away from the Olympic bubble, go into town to grab dinner dressed in your normal clothes (not in national team apparel).

These tips were extremely valuable and made me feel much better prepared. My research had paid off.

During the Rio Games, I coached five athletes in four different sports: wrestling, judo, high jump, and decathlon. Two had won Olympic medals during the London Games in 2012, one was a reigning world champion, and all of them were successful internationally in their respective sports. All five athletes had a chance to podium in Rio, and the Canadian sport system had high expectations for them. But this really hit home for me after I read an article that predicted how many medals Canada was expected to win, and four out of the five athletes I coached were on the list.

Bang! A second moment of self-doubt set in.

Four months remained before the opening ceremonies. I can still see myself sitting in front of my computer, flustered by this article. I sat back in my chair, my head spinning with skeptical thoughts: “What if the athletes aren’t adequately prepared? What if they perform poorly? Would it be because I let them down?”

My first reaction was to stifle the panic I felt inside. I pretended to be confident and in control, but the fake it until you feel it strategy wasn’t enough to manage the situation. The old macho hockey coping mechanisms were resurfacing, as in “no pain, no gain!” Talk about a bad approach. My sound-sleeping nights took a hit. I was carrying extra weight on my shoulders.

After a few weeks, enough was enough, and I decided to speak out. At the time, I was a member of a mastermind group. We were six mental performance coaches who got together on monthly Skype calls to discuss our goals, share best practices, and talk about our challenges. These like-minded individuals worked in Major League Baseball, the U.S. Army, the National Football League, and other areas of elite performance. During one of our calls, I told them about the pressure I was putting on myself. They listened closely, expressed their undying support, and shared some helpful tips. I felt supported and understood.

Ten minutes later, I received an email from Bernie Holliday, the mental performance coach of the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Dear JF,

Pressure is something to welcome because it means your quality preparation and successful performances have positioned you in a really cool spot to do something awesome.

Athletes who struggle, or worse, the ones who didn’t qualify for the Olympics are not going to feel any pressure in Rio because they haven’t positioned themselves in a place to succeed big. They have no chance to medal!

So, the fact that you’re feeling the pressure and the fear to do right by your athletes for these upcoming Olympic Games is a testament to your great work and your success — it means you’re the right guy for this!

What do you think was my first reaction when I read this? Happy? Not at all. Satisfied? Nope.

Relieved.

I was very touched. An experienced and accomplished colleague had just confirmed that I was the man for the job. I then shrugged off the huge weight that I had been carrying around with me for weeks. I decided that the pressure weighing on me would now become my ally. It had morphed into a deep feeling of pride. I suddenly felt very privileged.

Thanks, Bernie.

I printed Bernie’s email and took it with me to Rio in 2016, then PyeongChang in 2018. During the Games, the first thing I did when I woke up in the morning was reread Bernie’s note. His message had such a positive impact on my career that I would like to pay it forward to you.

Dear Reader,

Pressure is something to welcome because it means your quality preparation and successful performances have positioned you in a really cool spot to do something awesome.

Struggling, or worse, disengaged workers are not going to feel any pressure because they haven’t positioned themselves in a place to succeed big. They have no chance to succeed!

So, the fact that you’re feeling the pressure and the fear about future outcomes is a testament to your great work and your past success. You are an indispensable member of your organization. It means you’re the right person for the job!

Is this message relevant to you? I hope it hits the mark like it did for me.

This experience taught me some important lessons.

I had been dreaming of working with top Olympians to get them ready for the Games . . . and there I was. I signed up for this! When our dreams become reality, they often carry with them the pressure to succeed. We forget that achieving our goals can generate a sense of discomfort. It’s when we’re in it with both feet that reality sets in. I knew, too, that many mental performance coaches would have given anything to be in my shoes.

So, in the end, feeling pressure was a privilege. I was in the enviable position of being able to fulfill my dream, which was to help others achieve their dreams.

The word pressure never gets good press. It’s usually presented negatively, as in “I certainly don’t want any pressure.” Yet pressure isn’t always a negative factor that crushes us. Over the years, I’ve witnessed distressing situations in which athletes collapsed under the unbearable weight that pressure can generate. But in many cases, I’ve seen the opposite unfold.

I address the concept of pressure almost every day in my coaching practice. Through observation and experience, I would argue that there are, in fact, two types of pressure.

The first type is the one that comes from above. The sort of pressure that we carry on our shoulders and weighs on us. It can paralyze you and undermine your confidence. This pressure is directly associated with negative self-talk:

- I’m afraid that I’m not good enough.

- I don’t have the necessary skills.

- I only have two weeks to finish this project — I won’t make it.

This type of chatter can swirl in our minds at high speeds. We then become vulnerable, and when minor setbacks arise, it typically feeds the inner turmoil and makes matters worse.

The second type of pressure is the one that comes from behind. It’s the kick in the rear end that we sometimes need to push us forward. This inner chatter is usually constructive and realistic:

- I can’t wait to attack this project! It’ll be difficult, but I like the challenge.

- This exam will confirm how well I know my stuff. Let’s do it!

- I’m being offered a big job, but I’ve been dreaming about it for a long time. I’ll finally be able to use all my skills.

Positive pressure enables athletes to perform proactively. They’re up for the challenge and are focused on what they want to achieve. It keeps them on their toes. Negative pressure, on the other hand, will get athletes to perform on their heels. They are on the defensive as their thoughts are most likely associated with what they want to avoid.

Before we go any further, there’s a basic principle that we need to address about the pressure we feel: it’s a matter of perspective.

Pressure is not a situation, a person, a context, or an environment. Pressure is simply something we feel that is entirely constructed by our own minds. We are the source of the pressure.

I remember my hockey defense partner would fall apart when we played in front of large crowds. The poor guy, his nervousness would take over, and his performance suffered for it. In contrast, I usually played my best games when the stands were jam-packed.

Olympians post their best results during the most stressful moments. Ask Olympic champions how they felt just before their performance, they’ll tell you that it was the most stressful moment of their lives . . . and they won gold! Therefore, intense moments of pressure can also be beneficial, right? You must refuse to let the pressure rule over you and instead make it your ally.

Pressure also comes from below to make you go higher

Canadian high jumper Derek Drouin knows all about dealing with pressure. In preparation for Rio 2016, he boasted some impressive results and entered the Olympic year firing on all cylinders. Already a bronze medalist at the 2012 London Olympics, he added several victories to his repertoire, including Pan American and World Championship gold medals in 2015. Most of Derek’s competitors saw him as the man to beat in Rio. His sport federation and coaches were also confident that he was a serious medal contender: expectations were high. Third in London was great, but Derek knew that Rio was the perfect time to peak. He had to turn this pressure to his advantage and make it come from behind to realize his childhood dream.

Derek started his 2016 season like any other, slowly but surely. His fitness level evolved through steady, well-orchestrated improvements. Everything was happening as planned.

In April 2016, four months before the Games, Derek was suffering from persistent back trouble. Small aches and pains that require minimal care are normal, but he knew that this was different. The medical team conducted a series of tests, including an MRI. The results revealed horrible news: two lumbar vertebrae showed small fractures.

Derek found out he had a broken back four months before the most important moment of his life.

Can you imagine receiving shocking news like this? All sorts of emotions surfaced: anxiety mixed with anger, frustration, and concern. Clearly, the plan leading up to the Games had to change.

Two possibilities lay before him: he could embark on a specialized physical conditioning program to strengthen his lower back and hope that it would make it until the Games, or he could take five weeks off to allow the fractures to heal and still have ten weeks to pick up where he had left off.

It was a risky bet, but he chose the second option. Do you have any idea how hard it is for an athlete to step away from their sport, let alone a few months before the Olympics? Well, let me tell you, there’s nothing worse for an athlete than forced inactivity. They’re so invested in their sport, not being able to do it affects their identity and self-esteem. The same can be said for workers who are highly engaged in their careers.

Despite the uncertainty, Derek’s behavior was outstanding. He followed the medical team’s instructions to a T. He didn’t rush things. Even if he couldn’t train physically, he could still train his mind. He sensalized daily and slept long hours; Netflix became his best friend!

After five weeks, Derek felt substantially less pain. The prognosis seemed encouraging, and Derek was ready to begin training again.

As a precautionary measure, and for his own peace of mind, he decided to have another MRI to get an update.

The results showed that the fractures were still there, with minimal improvement.

I sensed that Derek was frustrated, and rightfully so. The danger was refusing to accept the situation and becoming bogged down in pondering Why me, why now? This is unfair. The temptation was strong to see the last five weeks as a complete waste of time.

The reality was that he was running out of time. The priority now was to look at the situation objectively, not subjectively. It’s much more constructive to deal with a situation than stubbornly fight against it.

It is what it is, not what it’s supposed to be.

To become an Olympic champion, Derek had to jump close to 2.4 meters, or nearly eight feet. That’s the height of a standard ceiling in a house. With ten weeks left, Derek’s support team understood that it would be tight. I asked him if he still believed he could win gold. Given his highly competitive nature, I was expecting a resounding yes! Instead, he said, “I don’t know because I’ve never had to prepare for the Olympic Games with a broken back.”

He was right.

It was much too early to think about the outcome of his event. To bring the conversation back on track, I then asked him if he thought he could get better by the end of the week. He thought so. From that moment on, the plan was to prepare for Rio with small short-term goals. The motto became, “Get better every week.”

Derek had five competitions leading up to the Olympics. He was able to jump 2.2 meters during the first event of the series. It was a far cry from the required 2.4 meters, but Derek remained realistic, reminding himself that, “It is what it is, not what it’s supposed to be. One week at a time.” His sole objective became to do a little better next time.

Kudos to Derek’s medical team and his jumping coach, Jeff Huntoon. They were instrumental in helping Derek improve his marks a few centimeters at a time despite the pain caused by his back. The fifth and final competition was held in Eberstadt, Germany, three weeks before the Games. Derek blew us all away with a 2.38-meter jump! At that precise moment, he knew that he could win Olympic gold in Rio.

Let’s fast-forward to the Games.

Rio de Janeiro, August 14, 2016. Derek posted a 2.29-meter jump to qualify for finals. Two days later, on a hot and humid evening, the 6-foot-4 Canadian stood in the enormous 78,000-seat stadium, preparing for the high jump finals. I sat in the first row with the other members of Derek’s support team, including members of B2ten. We were following every step of the way as Derek started at 2.20 meters, then 2.25m . . . 2.29m . . . 2.33m . . . 2.36m. The competitors are eliminated after three consecutive missed attempts, and at this point, most of Derek’s rivals had already thrown in the towel except for the Ukrainian and Qatari jumpers.

The bar was raised to 2.38 meters, with Derek scheduled to jump first. He knew it was doable as he had done it in Germany a few weeks earlier. From our vantage point, we watched him closely as he performed his pre-jump routine. Focused face, confident posture, deep breaths. We could sense that he was in his zone, experiencing this moment of intense pressure with true Olympian calm.

He was eyeing the bar like a lion stares at his prey: I’ve got this. Just before he started his approach, he simulated the jumping motions one last time to feel it throughout his body. Starting with a hop, he began his approach. In just a few strides, he arrived at the bar, planted his foot, and propelled his body through the air. He grazed the bar, but it held.

Derek cleared 2.38 meters!

We were ecstatic! His two opponents were now under huge pressure from above. Eventually, they both failed to clear the bar, and Derek was crowned champion.

That’s right, folks. Derek Drouin won Olympic gold with a broken back.

I jumped with joy and celebrated the moment with Dominick Gauthier and JD Miller, the founders of B2ten. Then I broke down in tears. Derek had accomplished his lifelong dream despite all the setbacks. His performance left me stunned. It was the first time as a mental performance coach that an athlete I was coaching had won gold at the Olympics.

That evening in Rio, all of us hugged each other and cried tears of joy together. What a moment! Grown adults, openly and genuinely showing their emotions. Almost seems strange, doesn’t it? You should try it at work. It’s an excellent way to create team chemistry.

I will be forever in awe of Derek’s achievement. He demonstrated such poise, resiliency, and maturity throughout the entire process. All of this in the face of extreme adversity and with the stakes so high. What an athlete!

I experienced an aha moment in Brazil. Living this journey with Derek right up to the gold medal confirmed that I was in the right field. I also realized how privileged I was to experience the pressure that comes with helping Olympians achieve their dreams.

Looking back, I recognize that Derek helped me go further. His extraordinary accomplishment under such difficult circumstances taught me four important lessons. I would like to share them with you so that you, too, are better equipped to deal with pressure.

Focus on short-term goals

Paying too much attention to a long-term goal can cause anxiety. It’s hard to get a real handle on the way things will evolve when we’re fixed on a deadline that is months away. Furthermore, things rarely if ever unfold exactly the way we imagined them anyway, so what use is it to be so obsessed with the future so far ahead? Keeping your focus short term, taking things one week at a time, can be reassuring. “What do I need to do in the next six days?” is far less distressing than “What do I need to in the next six months?” The next few days are within our reach, so the burden becomes lighter, and the tasks that need to be done are easier to handle. Short-term goals also help us acknowledge and celebrate the small victories to feed our fire. The get-better-every-week approach enabled Derek to focus on small gains, avoid discouragement, and stay away from the uncertainties associated with being able to compete or not in Brazil.

In the corporate world, executives often attach too much importance to quarterly and mid-year targets. Don’t get me wrong, medium- and long-term goals are important, but if you obsess about them all the time, how attentive are you to taking care of your daily business?

Whatever the challenge may be, you can get there, one week at a time.

Remember, it is what it is, and not what it’s supposed to be

Derek couldn’t ask the International Olympic Committee to postpone the Games for a few months because of his back injury. Qualifications were scheduled for August 14, and the final for August 16. Period.

People who are mentally tough have this ability to see things as they really are, whether good or bad, and just deal with them. Typically, we complain about situations when we don’t want to be challenged. The problem is that this negative mental framework prevents us from seeing the solutions and moving forward. Remember that it’s always easier to deal with a situation than to fight against it.

For example, you’re initially asked to produce a report within the week, but then your boss changes their mind and now wants it done within three days. Instinctively, you may get upset when thinking about the shorter deadline. But when there’s nothing you can do about it, what use is it to get overly worked up about the situation? It’s much more efficient to shift your outlook and adapt to the new reality.

Derek demonstrated that we can still achieve an exceptional goal, even in a very complicated situation. I often tell my clients, “Find a way to be amazing in crappy conditions.”

Accept pressure in your life

When I think back to Derek’s gold medal, it seems to me that his injury had a positive impact, not a negative one.

His injured back forced him to focus on only the basic elements to train efficiently. His preparation plan was reduced considerably, leaving him with no wiggle room to coast along without being purposeful. His back was against the wall. He had no choice but to be perfect every day in training. The pressure that Derek felt to be ready for the Games imposed robust self-discipline. Healthy pressure can make us superefficient, even when we’re highly vulnerable.

Take a few minutes to think about some pressure that you’ve experienced at the office.

- Do you see this pressure negatively or as a way to make you better?

- Do you use this pressure to improve your self-discipline?

- Does this pressure bring you back to the basics to ensure that you’re getting things done right?

My friends at Cirque du Soleil who are responsible for creating new shows feel enormous pressure in the months leading up to each premiere. When the tickets are sold out, you can’t waste any time. You must meet the deadline. In the home stretch, they work twelve to fourteen hours a day, six days a week. The show must go on! In retrospect, they recognize that they’re able to produce exceptional shows thanks to the pressure they feel leading up to the premiere. A veteran Cirque du Soleil choreographer was telling me that having too much time wasn’t necessarily better, because there was always the danger of becoming complacent and lazy.

If Derek had magically been allocated a few extra months to prepare for the Games, would he have achieved the same outcome in Rio? We will never know. But one thing’s for sure, he beat his own path to gold by maximizing the time he did have.

Maintain your goal even if the route changes

At work as in sports, there is always more than one way to reach the ultimate goal. Having an alternative plan is always helpful. If plan A is no longer working, we move on to plan B. It’s reassuring to know that there are other solutions.

Think of a situation in which you felt stuck at work. Things were not going as you had anticipated, and you’re racked with doubt.

Was it difficult for you to look at the situation differently? Were you able to come up with the right plan B? Would you approach this situation the same way were you to confront it again?

One of my close friends is a successful attorney specializing in corporate law. He uses a technique that he calls “answers in my back pocket.” When he’s getting ready to meet a client, he strategically anticipates all the questions likely to come up so that he’s never caught off guard. He also foresees all avenues that the negotiations could potentially take so that he can show up at the meeting with multiple solutions in his back pocket. I’ve rarely witnessed someone who comes up with answers to problems the way he can. His tag line is, “If options A, B, and C don’t work, no sweat. The alphabet has twenty-six letters.”

In Derek’s case, he was forced to take a totally different tack heading into the Games. He had to completely remodel the plan: the number of jumping sessions, the competition schedule, the training loads, and the recovery breaks. He had never prepared this way for a major competition. He had to let go of plan A and turn to plan B, which worked out perfectly for him in Rio.

Let’s define stress

I believe that the word “stress” is not always used correctly. Too many people use it as a generalized term to describe most of the negative emotions that we experience.

Stress is simply a reaction that our body experiences from dealing with a stimulus. In other words, when we go through any kind of change, we are stressed. The famous researcher Hans Selye determined that there is good stress (eustress) and bad stress (distress). The first relates to emotions such as joy, excitement, and enthusiasm, while the second refers to anxiety, frustration, and exhaustion.

We may look at stress negatively, but we actually need it to grow and excel. For example, the entire fundamental principle of sports training is based on inducing specific amounts of stress in the mind and the body to make them more powerful. Without these reactions to stress, they can’t respond to increasingly demanding challenges.

As a matter of fact, few people experience radically stressful variations as often as elite athletes do. They can be in full eustress when they win championships and in deep distress when performing less well than expected.

The effects of stress on our bodies is similar to the variations on an electrocardiogram. It’s better to see the ups and downs rather than a flat line, right? When a client arrives in my office and tells me they’re stressed, I say, “Great! That means you’re alive.”

The point is, stress doesn’t mean negative. An ecstatic moment of joy can be just as stressful on the body as an episode of intense frustration.

Make your butterflies fly in formation

Congratulations! You’ve just been asked to speak before a room full of people, the one thing that really makes you nervous. Just thinking about it makes you feel woozy. When the time comes, your heart is pounding, your palms are sweating, and you’re looking for the exit.

Because you dread these types of situations, you’re not in tune with the moment.

Nervousness is actually a good thing to experience. Put simply, it’s a natural mechanism that our brain triggers so that we can respond to an important challenge. We become nervous because the challenge means something, because we care. When was the last time you were nervous about something that you were indifferent about? Without nervousness, we wouldn’t be able to achieve our full potential.

A typical symptom that we feel is butterflies in our gut. Do you know what causes them? When the brain detects a threatening situation, it releases adrenalin, which can temporarily harm the digestive system. Blood leaves the areas where it’s not needed, such as the stomach, and flows towards other areas of the body, like our muscles, that are called upon to do more. Butterflies are small contractions caused by a lack of oxygen in the blood, so less blood in the stomach = less oxygen = butterflies. That’s all it is.

The problem isn’t the nervousness. On the contrary. Nervousness helps us prepare. Becoming nervous because we’re nervous is the problem!

Once again, it’s important to have the right attitude.

In the end, having butterflies is not bad, unless you decide it is. When Mikaël Kingsbury stood at the top of the course before his gold medal run at the Olympics, he had a whole army of butterflies in his stomach! Four years had passed since his second-place finish at the Sochi Games, and he was looking for revenge. This moment meant the world to him. We knew ahead of time that the butterflies would also travel to South Korea, but Mik wasn’t worried at all. He had a plan to work with — not against — the situation. When the butterflies finally showed up, instead of “Oh, shit!” buzzing in his mind, it was “Oh, yes!” One word can make all the difference.

Butterflies will always be there in times of major stress. After all, we’re humans, not robots. We just have to make sure that our butterflies fly in formation.

Butterflies heading in the same direction means having the ability to feel comfortable with the uncomfortable. This works while performing for a global audience, going through a job interview, or writing a test at school.

The impulsive brain

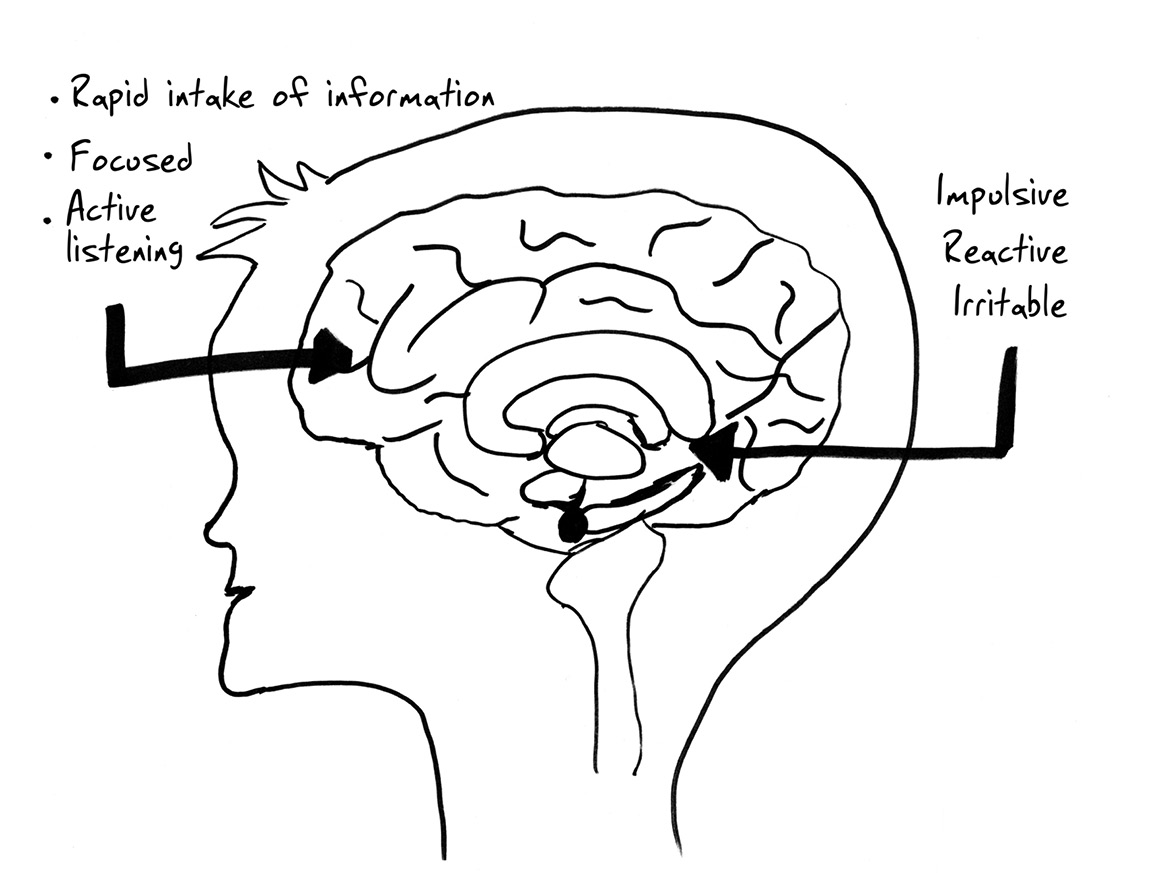

To explain how the brain operates in moments of high stress, we often refer to the example of a primitive human being who encounters a bear. The cognitive response to this threatening meeting is managed by the limbic system, also called the emotional brain. The primary function of this section of the brain is to ensure survival. It acts on impulse to protect us.

The involuntary reaction, commonly referred to as the fight-or-flight response, may be practical to protect ourselves from dangerous encounters, but it’s not very useful at work. When you have an impulsive reaction that you regret five minutes later, wondering Why did I say that?, know that your limbic system is to blame.

The prefrontal cortex, also called the smart brain, is the part of the brain that you want to prioritize at work. Located in the frontal lobe, it helps capture and analyze information to produce a desired response. The prefrontal cortex is responsible for great performances on the field and in the workplace, especially when there are stressful distractions everywhere. We’ll come back to this point later on.

Let’s get back to the emotional brain. Our limbic system is also responsible for generating the emotion of fear. In my work, I hear stories of fear every day:

- fear of disappointing

- fear of the unknown

- fear of not being up to snuff

- fear of risk

- fear of not being liked

- fear of failure

- fear of losing

- fear of getting injured

What is a fear? Does it really exist?

Fear is nothing more than a story we tell ourselves. Since it refers to a future event, there’s nothing that guarantees that it will actually happen. Yet we still convince ourselves to believe our fears. In the end, it’s only as intense as we make it.

Since our limbic system protects us against potential danger, we have a natural tendency to exaggerate the threat. The more we feed it, the more it scares us. However, after going through a daunting situation, we often realize that it wasn’t as terrifying as we had thought it would be.

In the end, it wasn’t that bad.

This means that the made-up story was worse than the actual situation. Think about the wasted time and energy! Based on experience, I would argue that approximately 80 percent of our fears never happen or, at least, not as we had imagined them.

Keep in mind the popular acronym FEAR: false evidence appearing real. It’s a simple way of remembering that most fears aren’t true and are often nothing more than a story that we’ve invented in our own minds.

Like nervousness, fear can also be our ally. Being afraid forces us to focus our attention on the basic elements to achieve our goals. If you’re scared to flunk your exam, you’ll modify your schedule to study more, right?

Canadian figure skater Tessa Virtue had her own acronym for the Olympic Games in South Korea. Remembering that FEAR could also serve as a launching pad, she loved this version: Face Everything And Rise. She wanted to attack the Games, not become a victim of them.

To better control your fears, ask yourself, “Do I need to be this scared?” Usually the answer is no. This simple question helps normalize the situation so that we can see it differently.

Once again, perspective is key. The way we manage fear determines its impact on our behavior.

Stop caring and let go!

I’ve noticed that one of the most common fears in the workplace is the worry of being judged by others.

- Does my boss think highly of me?

- Does the client appreciate my services?

- What do my colleagues think of me?

Learn to ignore it. Your time is way too precious! Besides, very few individuals will tell you what they really think about you. You don’t believe me? How many times have you told a colleague what you really think of them? Exactly.

As a keynote speaker, if I worried about what everybody thought of me, I wouldn’t sleep anymore! The truth is, we’ll never satisfy everyone, even if we try.

During a business trip, I met a speaker whose area of expertise is human happiness. She mentioned that what differentiates happy people is their tendency to let go more than their less happy counterparts do. In other words, stop caring so much, especially on issues that are out of your control.

Olympians are criticized all the time by judges, opponents, coaches, the media, and fans. They become very skilled at brushing off nasty comments or, at least, at taking them with a grain of salt. Sometimes, they just don’t care. They choose to remain focused on what they can control.

Do you worry too much? Do you wonder what other people say about you?

If you do, sometimes the most efficient method is to simply not give a damn! Don’t get me wrong, it’s important to respect others, but, for the good of your mental health, letting go of useless comments is highly beneficial. This strategy can help you deal with office gossipers, trying competitors, or social media critics.

Adjust your thermostat

Peter Jensen is a successful mental performance coach who has contributed to a number of great Canadian triumphs over the years. Known for his creative methods, he uses a thermostat as a metaphor to illustrate the ability to remain cool when the pressure’s on.

In our homes, we set the thermostat to a desired temperature, such as 72°F. The thermostat will then take into account the ambient variations and readjust to maintain a constant temperature. It dictates what the temperature will be. On the other hand, a thermometer doesn’t have the same adaptive system. It simply measures and indicates the temperature in a room but has no influence over it.

Elite performers manage themselves like thermostats: they stay cool when the heat is on.

To manage pressure better during competitions, one of the coaches I know wears a smart watch with a heart rate monitor to track his physiological state. As it is, he’s known as a leader who is constantly in control of his emotions and always says the right things at the right time.

We have to know ourselves well to self-regulate like a thermostat. Elite athletes spend so much time training their bodies, they intuitively develop amazing self-awareness. Their bodies send constant feedback to the brain indicating whether the drill is challenging, easy, tiring, comfortable, and so on. Subsequently, athletes understand what causes symptoms, such as:

- sweaty palms,

- dry mouth,

- stuttering voice,

- additional muscle tension; and

- quick heart rate.

To perform well, athletes must first know their optimal activation level. They can’t be too relaxed, but they can’t be too hyped up either. Have you ever heard the saying never too high, never too low? Think about guitar strings. To produce a perfect sound, they can’t be too tight or too loose. The same thing applies to human performance.

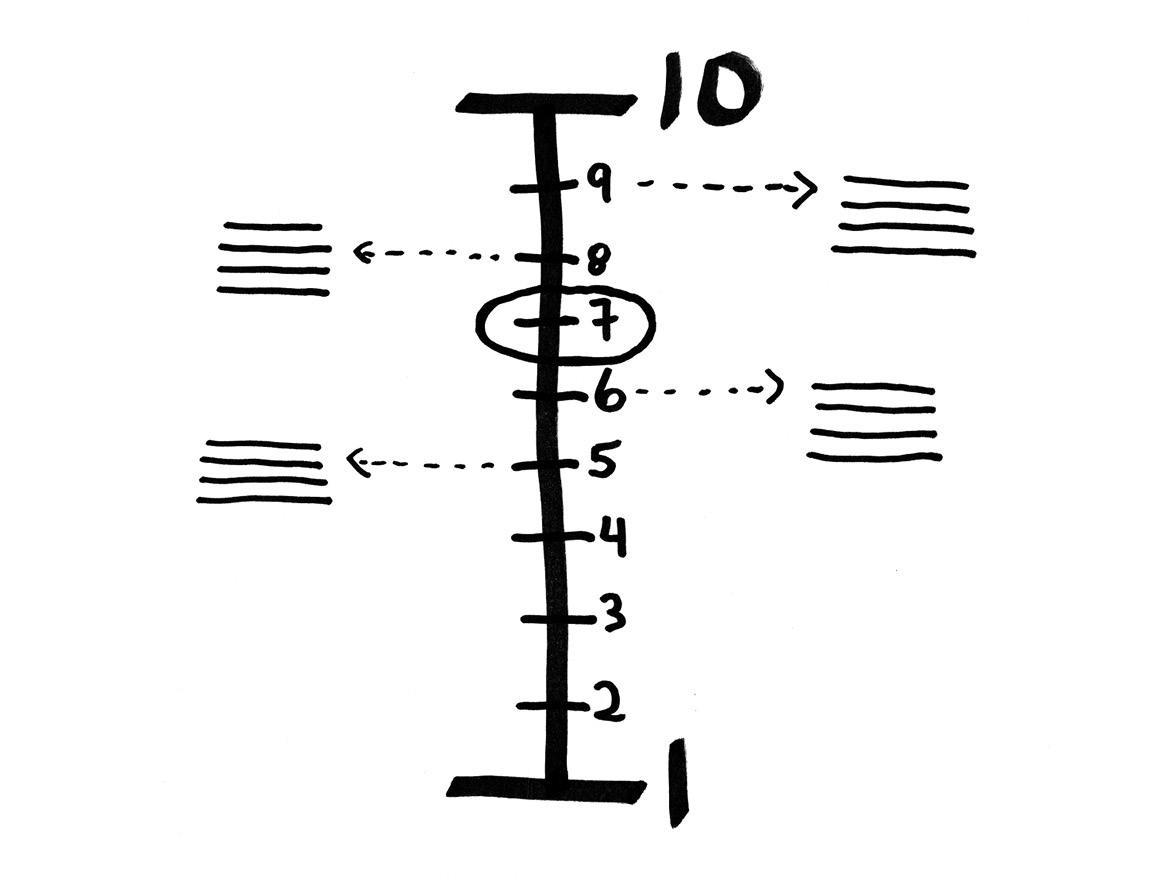

To help performers find a happy medium, I use a scale of 1 to 10. The number 1 signifies a state of deep relaxation, and 10 represents an excessive emotional state with little self-control. The first step is to determine the number that indicates the ideal level of activation. For a hockey player, this number could be 7; for a golfer, 5; and for a boxer, 8. Next, we describe what this number means. For example, when a tennis player is at 7, this means that:

- they’re relaxed physically,

- they’re maintaining a positive inner chatter

- they’re feeling confident; and

- they’re breathing well.

Numbers 5, 6, 8, and 9 are also defined to help the athlete understand what is too low and too high. Thanks to specific self-regulation techniques, the athlete is able to tone it down or turn it up to get back to their sweet spot, just like the thermostat that readjusts to come back to the desired temperature.

If you’re looking to better self-regulate, this scale is simple, concrete, and easy to use.

Activate your thermostat.

Fill your toolbox

There are plenty of ways to manage stressors to help us tap into our Olympian calm. To finish off the chapter, I will share a few of my go-to techniques. Hopefully some of them will serve you well.

Walking

We often forget that walking is the most effective and natural form of exercise there is. It doesn’t require a gym membership, a fancy piece of equipment, or a teammate to rely on. All it takes is a pair of comfortable shoes. It’s not the most strenuous workout, but it still produces endorphins, our brain’s favorite anti-stress hormone.

I regularly walk in my neighborhood on workdays. These short breaks always do me good. I mean, when’s the last time you felt awful after a ten-minute power walk, right? In addition to producing a sense of well-being, the brain stimulation you get from walking generates all kinds of creative ideas.

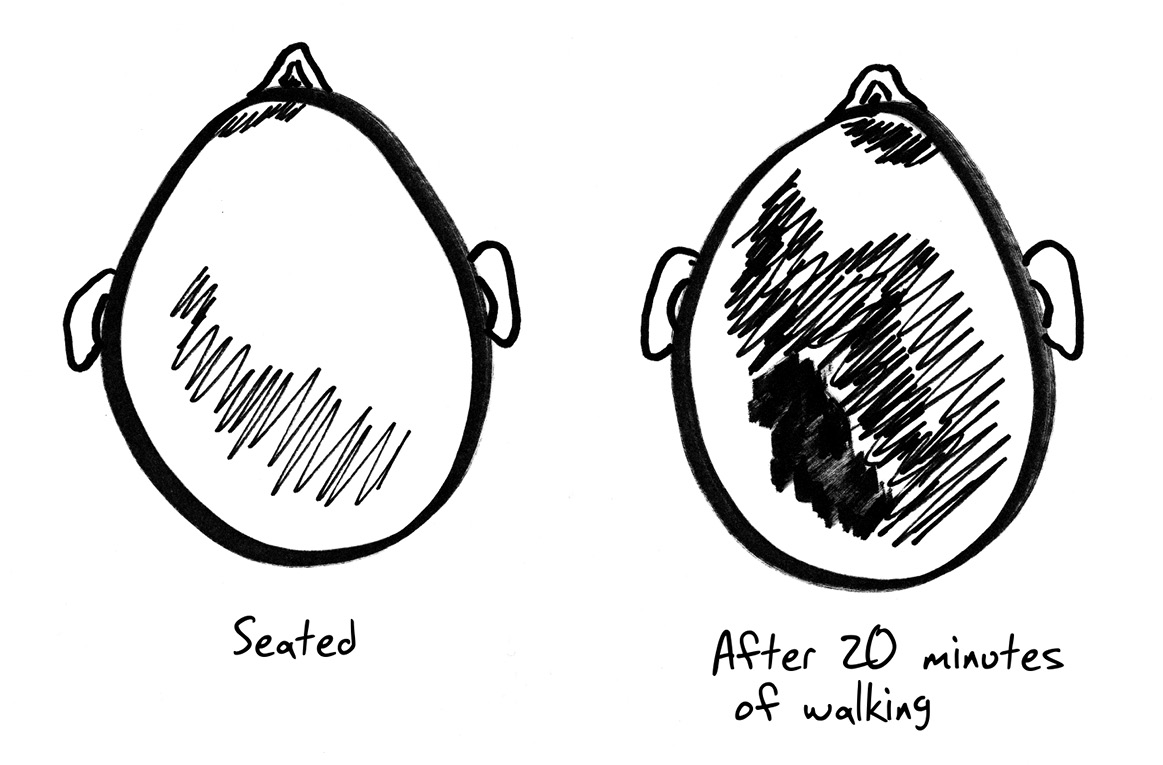

In 2009, Dr. Charles Hillman at the University of Illinois used brain imaging to show the difference between the brain of a seated subject and the brain of a subject who had just walked for twenty minutes. You can see the areas of the walker’s brain that are fully activated.

A client of mine who is a corporate leader for a beverage company will take a brisk walk when he feels his temper starting to rise. He refuses to be controlled by his limbic system! His five-minute power walk is enough to free his mind so that he can respond properly to the situation that provoked his anger. Now that’s a corporate Olympian!

Breathe like an Olympian

We breathe without being aware of it. It’s an automated process. But if we want to use our breath to calm ourselves down, we need to focus on it. Conscious breathing is a skill, and, like any skill, it needs to be trained if we want to use it properly. It gets rid of muscle tension and it diminishes neurological activity, but, more importantly, breathing has the ability to connect us to the present moment.

Do you practice conscious breathing? If you do, great. When I ask this question during a talk, very few people raise their hands. The most common excuse? They don’t have the time.

Conscious breathing (also called mindful breathing) is regularly associated with meditation practices such as being attentive to your breath for five, ten, or even twenty minutes. But you don’t need much more than a couple of minutes to benefit from it. Athletes learn to briefly concentrate on their breathing several times a day so that they can flush their minds and refocus on the task at hand.

Below is a simple-to-use breathing exercise that you can implement at work. All you need to do is find a comfortable spot in a quiet place and follow these three steps:

- Take ten deep breaths by taking three to four seconds to inhale and five to six seconds to exhale. Longer exhalation triggers the relaxation effect. If you need to activate yourself, do the opposite. When you exhale quickly, you increase your activation level. For those reasons, breathing is an excellent way to find your sweet spot on your activation scale.

- Inhale through the nose and exhale through the mouth (or the nose, if you prefer). It’s important to inhale through the nose, as its filtration system purifies the air before it reaches the lungs.

- While inhaling, expand the chest first, then the abdomen. When exhaling, deflate the abdomen first, then the chest.

Two minutes once a day is all it takes to notice some benefits. After a few weeks, you’ll start having more control over impulsive thoughts associated with stressful situations. If you are new to mindful breathing, there are some simple guided-breathing apps, such as Breathe Easy, to help you get started.

Breathing is free, and you can do it whenever and wherever you want. Use it!

Don’t be perfect, be excellent!

In his biography, former National Hockey League superstar Bobby Orr explained that he used to break down his seventy-game season into seven blocks of ten games. He understood that having short-term goals was smart. In each of these blocks, his objective was to play well during eight games out of ten, keeping some leeway for the lousy games that every player experiences once in a while. This method eliminated the pressure to be perfect. Instead, Bobby chose to work towards excellence.

Having a perfection mindset is a double-edged sword. It pushes us to set ambitious goals, but the risks of disappointment and discouragement are high. When perfectionist athletes don’t perform well, they experience agony and frustration, while extreme perfectionists feel anger, even rage.

I encourage them instead to develop an excellence mentality. Excellence doesn’t mean succeeding 100 percent of the time, but almost.

When you compare the two mindsets, it’s fascinating to see how different they are. Together with an elite athlete, I developed this comparative table, which has become a useful memory aid to help him prepare for a competition.

|

Perfectionist Mentality |

Excellence Mentality |

|

100% |

85–99% |

|

I will nail every element |

I will nail most elements |

|

Unrealistic |

Realistic |

|

Failure is inevitable |

Success is possible |

|

Mistakes are unacceptable |

Mistakes are expected |

|

Has difficulty adapting |

Easily adapts |

|

Unachievable results |

Results are achievable thanks to a plan |

|

Controlling |

Spontaneous |

|

Gives up |

Perseveres |

As you can see, the excellence mentality allows for mistakes to be made and generates far less negative pressure. It deals with reality, not fantasy.

Let’s take a multiple-choice exam as an example. The perfectionist believes they know everything. They start the exam in full force. Then, they arrive at question 10, which they can’t answer, and they start panicking. They struggle to proceed to the subsequent questions because they keep thinking about question 10. On the other hand, students with an excellence mindset walk into class telling themselves they know a lot about the subject. When they get to question 10, they remain calm and move on to the next question, as they understand that excellence is still possible, even if they answer this question incorrectly.

Take a step back

If I asked you to stand with your nose pressed against the wall and to tell me what you see, you wouldn’t be able to tell me much more than the paint color, right? Now, if I asked you to take a big step back, you would see the picture frame on the left and the window moulding on the right.

When a client says to me, “I can’t stop thinking about x,” I make them stand up, press their face against the wall for one to two minutes, and describe how they feel and what they see. Then I make them take a step back. Usually, those who go along quickly learn the lesson: without perspective, we don’t see much.

In a problematic situation, taking a step back helps us see things more clearly. If an issue keeps spinning around in our minds and monopolizes our thoughts, we’re not able to grasp the answers.

Sometimes, all you need to do is to step away and come back to the issue later. The old cliché sleep on it is a great example. Delaying making an important decision until the following day allows for more time to consider it and even to generate some new ideas.

I said it earlier — it’s not the problem that’s the problem, it’s the way we look at it. So, take a step back!

Find the right words

We need to be careful about the words we choose to describe how we’re feeling. When we use the word stressed to describe our current state, we’re generalizing our emotion instead of indicating exactly what it is that we’re experiencing.

Are we feeling frustration, exasperation, nervousness, or fear?

Despite apparent similarities, there are important subtleties that distinguish our emotions. By using the right word, the one that describes exactly what we’re feeling, it becomes easier to find solutions.

When I help a client accurately define what they’re feeling, I notice that they’re somewhat relieved. “Yes, that’s exactly it!” It’s always easier to unravel a negative emotion when we’re able to put our finger on it.

An Olympian had this bad habit of referring to all unpleasant situations as problems. I made him realize that this word got his limbic system firing, probably more than he wanted. Since he is a perfectionist, it created additional unnecessary pressure that weighed heavily on his mind. Together, we decided that words like challenge and situation would be easier to handle. These words were far less threatening and enabled him to behave more calmly. With them, he had switched to the smart brain, the prefrontal cortex.

Sometimes, we need someone else

There are times when we feel stuck. We just don’t know how to respond to the challenging situation ahead of us. Caught off guard, we scramble to find answers. The tool that we can’t find in our own box may be in someone else’s. All we have to do is ask ourselves what this trusted person would do in this situation, and we may just hit the nail on the head.

Judoka Antoine Valois-Fortier uses this strategy every so often. He’s mentioned to me that Nicolas Gill (his judo mentor), Scott Livingston (his strength and conditioning coach), and I were three coaches that always gave him sound advice. If he runs out of ideas to manage a stressful moment, he asks himself, “What would they tell me right now?”

Who is this person for you, the one who always seems to offer the proper guidance?

Avoid dramatizing

When things don’t go as expected, high achievers tend to dramatize and exaggerate. For example, many hockey players place way too much emphasis on the oh-so-important first shift of the game: “My first shift wasn’t good. I won’t have a good game today.” I knew a volleyball player who had a similar mentality. If she made a few bad bumps early in the game, her brain would jump to conclusions such as, “I just don’t have it in me today.”

What about you? Do you dramatize and jump to conclusions when you struggle early in your workday? “I’m off today!” or “Oh boy, I’m in for the long haul!”

A bad morning doesn’t equal a bad day. A bad day doesn’t equal a bad week. And failing doesn’t mean that you’re a failure.

Besides, you really don’t need to add fuel to the fire considering your limbic system already dramatizes instinctively, right?

“?” or “!”

I was in a treatment room with an Olympian and the athletic therapist at the PyeongChang Games. It was the day before the competition. We were talking about everything under the sun while the athlete was getting treated. All of a sudden, I noticed that the athlete was no longer participating in the conversation.

“Cat got your tongue?” I asked.

“Yeah, sorry,” he said. “I’m asking myself a lot of questions right now.”

“Are you answering them?” I quickly replied, grinning slightly.

The athlete looked me right in the eye and said, “Heck no! That’s why I’m so mixed up!”

Questioning is generally synonymous with feeling uncertain and worried. I explained to the athlete that questioning ourselves (?) in pressure moments is normal, but we have to offer our brains convincing answers (!) to turn the inner interrogation around.

The next day, after having warmed up for the event, the Olympian came over to me and said, “Hey JF, I’ve got a lot of answers today. I’m going to nail my performance!”

Inner chatter ending with question marks leads to self-doubt. Constructive affirmations ending with exclamation points lead to self-assurance.

Does your self-talk have more “?” or more “!”? If your brain is throwing questions at you, make sure you give it the answers it deserves. Otherwise, your mind will get caught up in assumptions, doubts, and worries.

The CRAP method

A professional hockey player had trouble controlling his emotions on the bench after a bad shift. He kept using the word crap to describe his performance. “That shift was crap!” His words, not mine!

The player needed a specific guideline to manage himself on the bench. To make the technique catchy, I used my creative thinking and came up with crap as an acronym. C was for calm. Taking deep breaths would help him ease the inner turmoil before moving on to the second step, R for reflection. Once he was calm, he would be able to reason objectively, see the situation as it was, and understand why the mistakes happened. “I rushed the play and made a blind pass. That explains the giveaway.” Next came A for adjustment, replacing the mistake with a solution using sensalization: Take a second to look up before making the pass. The last letter, P, was for preparation. This step would make him go back to the important reminders that he had set for himself before the game.

Calm

Reflection

Adjustment

Preparation

The Olympian at work has to find ways to manage overwhelming stress. We often have to face the unexpected, just like athletes do on the playing field. To respond appropriately, we must calm our minds to tackle challenges effectively.

In the next, final chapter, we’ll address topics like perseverance, grit, courage, and determination.

With just one chapter to go, we’re almost at the finish line. Don’t stop now!