CHAPTER 1

Seize Every Opportunity to Learn

All the athletes I know have one thing in common: they have a strong desire to excel. They are constantly looking to become stronger, tougher, and faster. Their daily motivation is to simply get better.

Figure skaters Scott Moir and Tessa Virtue exemplify this constant striving to improve. During their illustrious career, Scott and Tessa won the most Olympic medals in the history of figure skating while also becoming the first North Americans to win Olympic gold in ice dance. Their success had nothing to do with luck. They used strict training methods with military-like discipline. Ultimately, their approach was plain and simple: every day they would ask themselves, “How can we be better?”

During our mental training sessions, Scott and Tessa took reams and reams of notes — Tessa alone filled two large notebooks! Between appointments, they constantly reread their notes from the previous week so they could apply the mental training strategies during practices. Before they showed up for sessions, I had to make sure I was ready, because as soon as they sat down in my office they began peppering me with questions:

- How can I stay focused when my legs feel dead?

- What can we do to trigger a burst of self-confidence just before stepping out on the ice?

- How can I remain calm and regain control when my inner chatter is negative and pessimistic?

- What can we do to improve communication with our coaches?

They challenged me and everyone else on their team: their skating coaches, their nutritionist, their strength and conditioning trainers, and their therapists. Every small lesson learned was taken seriously. They brought their notebooks everywhere to ensure that they didn’t forget anything. They would go over their notes regularly, whether on a plane, over coffee, or at the rink during warm-ups.

They were surrounded by a dozen experts in a variety of disciplines to help them prepare for the 2018 Games in PyeongChang, their last appearance on the Olympic stage. Nothing had been left to chance. Scott and Tessa wanted to show up in South Korea with the feeling that they had done all they could and be able to say, “We’re ready.”

I can confirm that they were indeed ready. I witnessed two athletes on a mission. The work had paid off, as they became Olympic gold medalists for the second time on February 20, 2018.

Scott and Tessa were students of the game. This expression refers to an intrinsic thirst for knowledge, a need to continually seek opportunities to grow and improve. Students of the game gather piles of information from their experts so they can show up at a competition certain that they’ve done everything to achieve the hoped-for outcome. These types of performers know that if you want to fill your toolbox, you have to want to open it first. Well, to learn just about anything, first you need to open your mind. You must choose to become your own best coach.

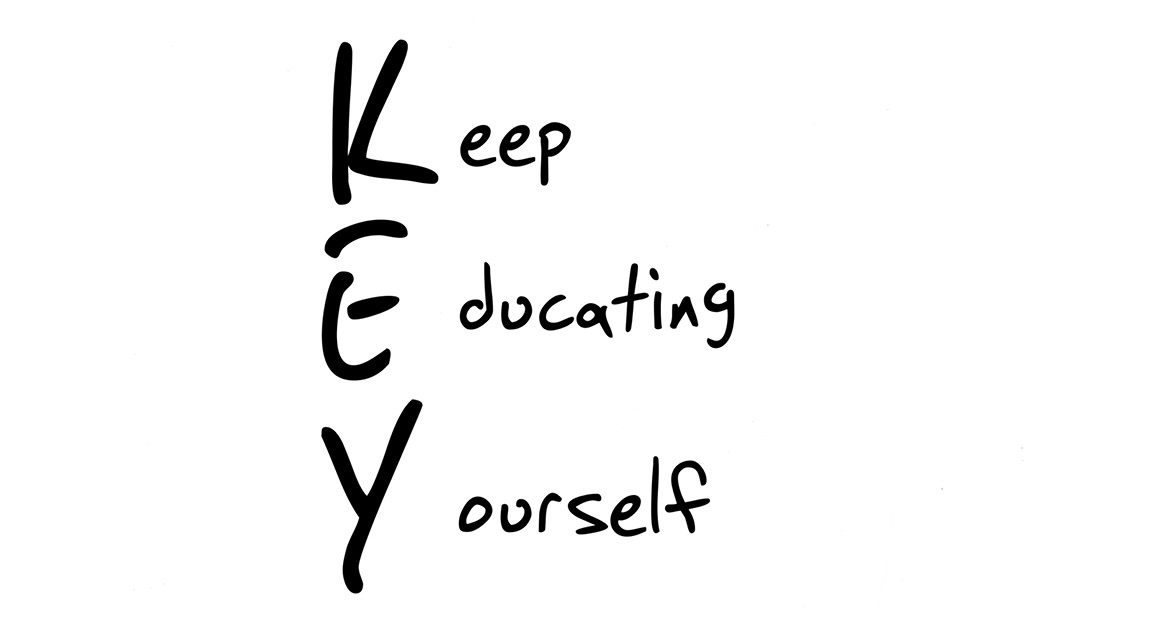

The key to success

In 2015, an elite sports academy in Luxembourg invited me to give a talk to staff and students. The first thing that struck me when I walked into the main gymnasium was an enormous vertical banner on which the following was written:

What a powerful message for teenagers! Student athletes and staff members couldn’t help but notice the poster as they walked by it every day. It was the school motto. Their unwavering attention and numerous questions during my talk blew me away; it confirmed their thirst for learning. After this experience, I, too, drew inspiration from this acronym, not only for my own self-improvement but also to help my clients during coaching sessions.

Elite athletes are masters of the KEY philosophy. They’re hungry for knowledge day after day, even if the lessons learned are small. They carefully gather all the information that can help them improve. Oftentimes, it’s the tiny details that can translate into shaving a few milliseconds off their time, and milliseconds can make the difference in getting on the podium or not. Small things can have a big impact. Think about that little drop of water dripping into the sink. It’s practically nothing, yet powerful enough to catch your attention and bug the heck out of you! Well, little gains on the playing field can have the same significant impact.

Mikaël Kingsbury is another exceptional learner. At the age of 28, this moguls skier is both a gold and a silver Olympic medalist. He’s won nine Crystal Globes, the trophy awarded annually to the best freestyle skier in the world. He’s stepped onto the podium 91 times in 109 World Cup starts. Of these, he’s climbed to the top of the podium 63 times. Did I mention that he is also a four-time world champion? Yeah, no wonder his nickname is the King!

During one of our sessions, I asked Mik why he so completely dominated his sport. Why isn’t there someone else like him? My questions caught him a bit off guard, so he thought about it for a few seconds, then answered.

First, Mik replied, “No one is as obsessed about the details as I am.” It’s true. Mik carefully analyzes each of his opponents’ runs while waiting for his turn.

Second, he added, “I make it a point to learn a little something new each day. I like to go to bed at night knowing that I’m better than I was when I woke up in the morning.” Once again, it’s so true. He finds a way to lift a little more weight than the last time. He becomes stronger. He adjusts the position of his ankles while zipping down the moguls course. He becomes faster. He makes sure that he takes away something new during each of the mental training sessions. He becomes more confident.

Mik is always looking for opportunities to learn. He loves every challenge I throw at him: big or small, he never backs away from them. He wants to be challenged, because challenges are opportunities that have to be seized.

Success isn’t based on luck. Success comes down to a limitless desire to learn. Great athletes understand that being successful isn’t about measuring up to others. It’s all about measuring up to yourself.

The experience of learning

The concept of having experience deserves some thought.

Many individuals believe that just exposing themselves to different situations and work environments over the years invariably leads to learning important lessons, making them better at what they do. This isn’t exactly the case. The best learning experiences happen when we have clear intentions. Purposeful, intentional, and meaningful goals will help us really progress.

At work, we constantly talk about the importance of having experience. For example, we may say that a person has thirty years of experience in their field. What does this mean exactly? If the experience we’re talking about is repeating the same routine day in, day out, without feeling engaged and with no clear intentions, what value does it really have?

In contrast, another candidate may have no more than ten years’ experience; if this career path is the product of a well-thought-out approach based on clear intentions and reaching specific goals, we’re talking about a purposeful working experience that may carry more value than that of someone who’s been at it three times as long.

Most of the people who operate according to strategic learning principles are fans of self-assessment and peer feedback. A participant at one of my talks was wondering how to get better at leading important meetings. I suggested that he film his next boardroom meeting and analyze it afterward, just like athletes do with video sessions after games. Video doesn’t lie; it tells the cold, hard truth! The answers are self-evident, and what we learn from video analysis is priceless. If you’ve never watched yourself perform, it may lead to vulnerable feelings, but hey, getting out of your comfort zone is what becoming an Olympian at work is all about.

Don’t get me wrong, you can still evolve if you go about your business with a punch-in and punch-out approach, but if you truly want to grow quickly and become a high-performer at work, then the purposeful experience approach is the way to go.

Having experience is a fairly arbitrary concept. In the end, personal development is mostly based on what we gain from our experiences, rather than just gaining experience, and our ability to use the lessons learned to improve our skills.

Even the King makes mistakes

Let’s turn back the clock a little. It’s January 2017, and we’re in Lake Placid for the FIS Freestyle Ski World Cup. This picturesque village in upstate New York also hosted the 1932 and 1980 Olympic Games.

It was Friday the thirteenth (no, I’m not superstitious), and the men’s moguls event was about to take place. Mikaël Kingsbury dominated the international circuit at the time.

Mikaël had podiumed during every World Cup since March 2014. He was on fire, so his goal was to keep this impressive streak alive. He started the day with a bang, zipping down the course with laser-like precision during his qualifying run. Everything had been going well up to that point.

Then came the final round. Six competitors remained. Mik was one run away from another victory. His game plan was to keep his hips forward, control his speed, and let his skis do the rest. He was waiting for his turn when American Bradley Wilson pushed off. As expected, the home crowd went crazy. Carried along by his American fans, Wilson ripped through the course with blistering speed. The judges were impressed and rewarded the local favorite with a big score, putting Wilson temporarily in first place. Kingsbury was perfectly aware that the American had put down a remarkable run that was going to be hard to beat. Usually Mik stays cool and collected in this kind of situation. Not this time.

Overcome with emotion, Mik pushed his game plan aside and attacked the course with a vengeance. Bad idea. He made a few uncharacteristic mistakes and finished sixth. It was his worst result since another sixth-place finish in Lake Placid three years earlier, almost to the day.

Over the days that followed, Mik and I discussed at length what had happened. He came to the conclusion that he hadn’t been focusing on the right thing. He had let his ego take over — “I’ll show him who’s the King” — instead of sticking to the established game plan. We reviewed some important lessons so he could approach this kind of situation differently in future.

Well, the future arrived a lot faster than anticipated. During the following weekend, another World Cup was taking place at Val Saint-Côme in Quebec. Mik found himself in almost the same situation, but this time, the King of moguls skiing was ready to face some adversity and keep his ego in check.

This time, Mikaël stayed true to his game plan to reach the top step on the podium. The local favorite was greeted by family and friends to celebrate his bounce-back victory. That’s all Mikaël needed to kick off another impressive streak. Between the Val Saint-Côme World Cup (January 2017) and the PyeongChang Games (February 2018), Mikaël competed in sixteen World Cups; he won fourteen gold and two silver medals. An ideal preparation for the Olympic Games!

Events sometimes have a funny way of turning out. It’s January 2019, Marie and I were drafting this anecdote, and my phone started ringing. My screen displayed Mikaël Kingsbury. Marie and I were blown away. What a coincidence! I picked up. “JF, it’s Mik. I just finished my race. I screwed up. I wasn’t focused enough. I caught my ski on a mogul and I finished fifth.” He had just competed in a World Cup in Lake Placid of all places. Let’s just say upstate New York isn’t Mik’s favorite place!

The student of the game went to work; Mik reflected, analyzed, and fine-tuned his skills. He made the necessary adjustments to succeed again. The following weekend, he won another World Cup in Mont-Tremblant, Quebec. Two weeks later, he achieved his season goal by winning two gold medals at the World Championships in Deer Valley, Utah. The King had bounced back once again.

This anecdote illustrates exactly what I mean by learning in a purposeful way. Mikaël’s experience in Lake Placid was a milestone, and his intention to make it a turning point was clear. This is what purposeful learning is all about: experience that leads to important lessons that can be applied to making yourself better.

When you’re not performing to your own expectations, ask yourself, “Why? What happened?” just like elite athletes do.

There’s no point in criticizing yourself too much. By remaining objective, you’ll focus instead on the details that explain your poor performance and come up with solutions to bounce back.

Forget about operating on autopilot

Autopilot is practical for aircrafts and ships. The system corrects the course automatically when the vehicles deviate from their routes.

Humans don’t have an equivalent system to bring themselves back on course when they start to drift. Correcting their trajectory requires voluntary, not automatic, self-awareness and introspection. We’ll come back to this in greater detail in Chapter 6, “Develop an Olympian Calm.”

Athletes never rely on autopilot. They never settle for status quo or take the easy route. It’s quite the opposite, as they want their training to be difficult and challenging. Athletes don’t need someone else telling them to improve; they create their own opportunities to learn.

Because of the repetitive nature of training, athletes can easily choose to switch to autopilot. Every day, they go to the gym, meet their coaches, and repeat some of the same exercises. It’s the same for workers. Every day, they show up at the office, cross paths with the same colleagues, and pick up their duties where they left off.

Cirque du Soleil performers also understand the danger of routine. Some perform up to 475 times in a year, doing the same choreography, dressed in the same costume, and performing the same act in the same theater.

Of all the artists I’ve coached at Cirque du Soleil, the clowns were my favorite performers to work with. Clowns are the heart and soul of the show, and most of them have fascinating life stories. They’re arguably the most brilliant and creative, as well as wisest human beings I’ve ever met. If you ever have the chance to have lunch or grab a drink with a clown, do it!

The one clown who impressed me the most always avoided being in his comfort zone.

“I’ve watched you perform several times over the years, and, each time, I found that you were better than the last time,” I once said to him. “The pleasure that you portray on stage is palpable; it’s like it’s always your first show. How do you do this when you perform the same show every night?”

“You’re wrong,” he replied. I was thrown for a loop by this answer. “I never do the same show twice, because the people who come to see me are always different. New crowd, new show!”

“What are you trying to say exactly?”

“Listen, JF. When I go to pick people out of the crowd to join me onstage, I force myself not to choose those who are ready to jump out of their seat. I make a point of picking those who are going to be a challenge. I have to improvise to find the right way to convince them to follow me onstage.”

No wonder he was such an amazing performer. The important lesson here is to challenge yourself and leave your comfort zone if you want to excel. This particular clown was never afraid of becoming vulnerable, not even in front of a full house. Vulnerability opens the door to new experiences.

To become an Olympian at work, it’s not enough to just put in the time and hope to evolve quickly. You need to take personal initiative and make a conscious effort to continue to learn. Below are a few examples:

- Read a book that will add a tool that is missing from your toolbox, such as a new communication skill.

- Take a course on a subject that excites you, such as learning to speak another language, to sew or cook, or to understand the stock market.

- Join a discussion group for professionals in your field to share with, learn from, and support each other.

- Improve your breathing technique to better face a stressful situation, such as managing a complex file at work.

- Register for a seminar to become technologically savvy.

No one wants to be the employee who had so much potential. On the contrary. You want to be the one who embraces their potential. Athletes choose to work daily at getting better. If you want to become an Olympian at work, you have to choose to seize every opportunity to become a valuable asset for your employer.

As a mental coach, I constantly remind my clients to find projects that make them “vibrate.” Basically, any activities that sparks excitement while helping them develop and making them happy. Athletes take pleasure in their search for excellence. They play their sport. Don’t be afraid to change your routine and do the things you like to do. Tennis on weekends. A movie on Tuesday evenings. A coffee with a friend on Sundays. Happy hour with a friend on Wednesdays. These spurts of pleasure will have a positive influence on different aspects of your life, including at work. So, get out there and vibrate!

Curiosity: a secret weapon

Antoine Valois-Fortier is one of the most accomplished judokas in the world. His obsession with details sets him apart from the others. When he was in high school, he would hide during study period and watch past world championships and Olympic Games on VHS. He knew the content of each cassette by heart. He is a true student of the game. Ask him who won gold at the World Championships of 1993, 2001, or 2007, and he’ll list the names in a single go, without hesitation.

Elite athletes are curious creatures, always looking to reach new heights. Their quest for gold is an adventure into the unknown, like a treasure hunt.

As the saying goes, you don’t have to be sick to get better. Top athletes don’t wait to be weak to get stronger or until they are slow to become faster. It’s about getting better regardless of where they are in the process of reaching their goals.

We shouldn’t feel this urge to learn only when we have to solve a problem at work. We should feel it well in advance. Your process needs to become proactive. You may argue that it’s important to know our flaws and weaknesses. You’re right. We have to know ourselves well enough to identify what needs fine-tuning, and we must be humble enough to take action to address these deficiencies.

For example, you acknowledge not having given a colleague your full attention during yesterday’s meeting. You also notice that this happens more often than you’d like. You could easily brush it off and move on because it’s not a big deal, but you realize this behavior isn’t optimal for team success. So, you decide to address the situation by apologizing and by challenging yourself to pay closer attention to what she’s saying in future. Responding like this demands personal introspection, discipline, and humility. You take responsibility for your actions and decide to respond positively to improve on the situation. The word respons-ibility says it all: it’s the ability to be responsible.

Unlike the body, which slows down as we get older, the brain is designed to evolve over time, so it can continue to get stronger and smarter late into our lives.

I hugely admire people in their senior years who are in tip-top mental and physical shape. You know them. They’re almost eighty, they have a spark in their eyes, muscular calves, and energy to spare. I love chatting with them to understand how they stay in such great shape. One energetic senior once told me, “JF, the day you stop challenging yourself is the day you start to die. I have a bunch of friends who have been dead for a long time.”

What’s better: adding years to your life or adding life to your years? I’ll leave you to think about that.

My clients who are workplace Olympians go about their business with a state of mind called kaizen (“kai” meaning change, and “zen” meaning better or best). This Japanese expression refers to a series of small improvements made in tiny, continuous doses. Ultimately, curiosity is the secret weapon that most high performers utilize to be able to live a kaizen lifestyle.

Being solid on your feet

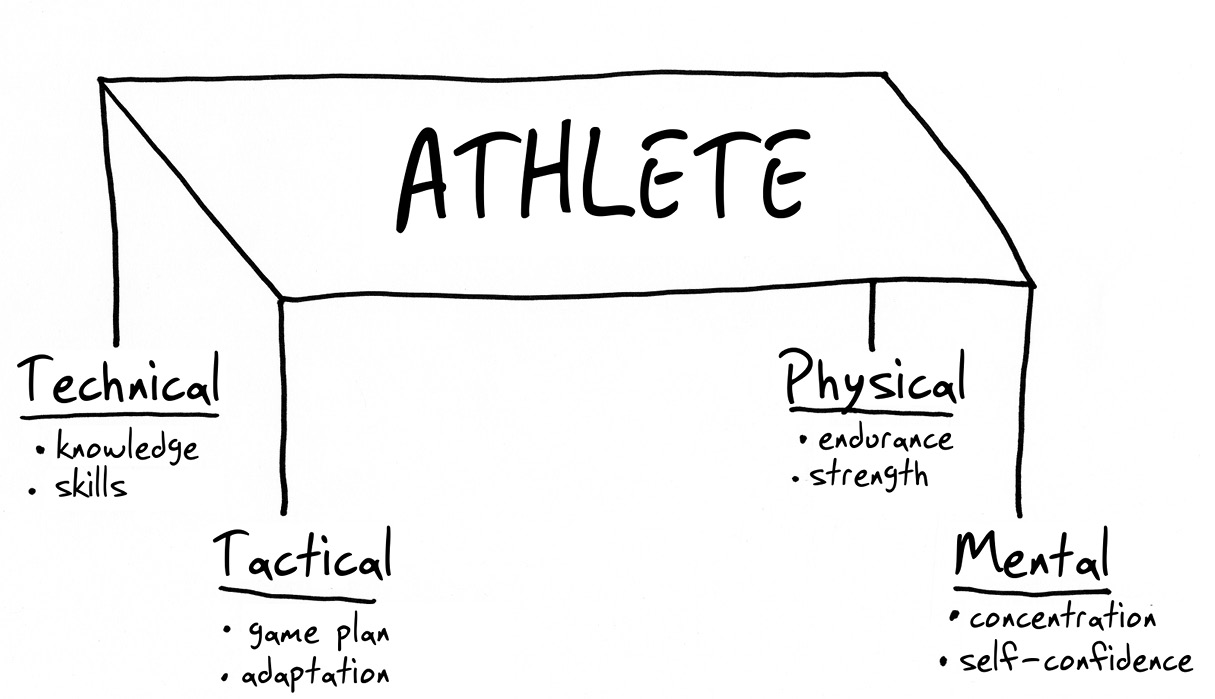

You get my point. To evolve we have to challenge ourselves, like the Cirque du Soleil clown and Olympic athletes do. However, to get there, we have to see performance as a whole. To illustrate the principle, let’s use your office desk as a metaphor.

To be able to perform under challenging circumstances, an athlete has to consider every aspect of their performance in order to be balanced, sturdy, and stable, so to speak. If one of the four training components (technical, tactical, physical, and mental) is neglected, they’ll be unbalanced, in the same way a desk is unbalanced if one leg is shorter than the others. The same principle applies to the Olympian at work.

You can have the most specialized knowledge (technical), you may come up with the best sales strategy (tactical), you may feel you’re in shape and well rested (physical), but you won’t succeed if you don’t have the proper mental skills to stay calm and be confident when under pressure. You won’t be solid on your feet.

In the world of elite sports, successful athletes typically have the full package. Their desk has four long legs. It’s practical for workers to go about their overall skills training the same way.

Do things right!

“Just try your best!” We hear this all the time. But what does it mean exactly? The statement suggests that the result to be achieved isn’t clear, which leaves some room to error.

A colleague was telling me that his boss had once written an important letter that was full of spelling mistakes and addressed to the wrong person. Unacceptable, wouldn’t you say? He was clearly in a rush and simply wanted to get it done quickly. Therefore, he certainly had no intention of writing a letter by the book and being respectful of its recipient. Simply trying to do his best was clearly not good enough.

When we do things in a careless manner and cut corners because we want to save a few minutes, we have to ask ourselves how much time we would need to correct our mistakes and make things right. Is it really worth it in the end?

Every national sports organization has a clear mission: to shoot for the podium at the Olympic and the Paralympic Games. In Canada, prior to hosting the 2010 Vancouver Olympic Games, an organization known as Own the Podium was created to help sports organizations describe their gold medal profile. This profile outlines the precise skills athletes will require to become champions in their discipline. This profile is then used by organizations to develop detailed yearly training programs, also known as YTPs. These twelve-month plans indicate what each athlete should be doing from one week to the next in order to peak at the right (Olympic) time. Each training session has its purpose. We ensure that everything has its purpose so that nothing is left to chance. The Olympics take place every four years, so it would be risky to settle for just trying to do our best.

In the workplace, most organizations define their company mission, vision, values, and goals for the year. Why doesn’t an employee do the same thing by creating their own gold medal profile for work?

Defining a clear game plan with strategic checkpoints along the way is key to achieving career goals. Ask any Olympian what lies ahead in the coming year. Believe me, they’ll know. And if they were to ask you the same question, would you be able to explain your own YTP?

We rarely think to ask ourselves, “What did I do today that will help boost my career?” Clear and precise intentions are the principles that guide us throughout our professional development and ensure that our daily actions have a real impact on our ultimate goals.

“Delicious uncertainty”

Every day at training, an Olympic athlete is working to improve, whether technically, tactically, physically, or mentally. Daily goals could include things like

- moving faster,

- listening better to the coach’s feedback; or

- perfecting conscious breathing between sets.

Oftentimes, the athlete writes these daily goals in a journal, discusses them with their coach before practice sessions, and goes back to the notes again during practice, if needed.

You can use a similar method at work. For example, a client of mine, the CEO of a small tech company, uses the first ten minutes of his day at the office to write what he calls his reminders for improvement. Below are a few of them:

- speak to each of my employees

- take short breaks (maximum time without a break: ninety minutes)

- be selfish and protect my schedule (say no to demands that will eat up my time)

These reminders appear on his desktop for the day. Out of sight, out of mind, right? Well, for this corporate leader, it became within sight, within mind.

Paying attention to details does not guarantee success. In fact, Olympians deal with failure more often than triumph. This may seem paradoxical, but it’s true.

Let’s say that if an Olympian sets goals that are well below their skill level, the likelihood that they’ll achieve them is very high. However, their level of satisfaction will be low. You don’t become an Olympic champion by setting easy goals. Becoming a champion requires getting out of your comfort zone through tough training conditions. The athlete wants to feel vulnerable and suffer pain, key components of self-growth.

To get the best out of your employees as a corporate leader, you have to put them to the test by demanding neither too little nor too much, but just enough. You need to find their sweet spot. To be able to do this well, a manager must assess employees’ skill sets and detect where they are in their progression, just like a sports coach does with their athletes. This process then helps determine the best challenges to set for each of them.

For instance, if you ask an experienced and well-trained employee to tackle an easy challenge, they’ll get bored. If you ask an inexperienced worker who lacks self-confidence to undertake a highly complex challenge, they’ll become anxious. But if you suggest a challenge that perfectly matches the employee’s skill level, they’ll be motivated and excited to carry out the task. Eventually, these challenges will help the employee maximize their potential.

This approach is based on a model developed in 1988 by Dr. Jean Brunelle and his colleagues called délicieuse incertitude, or delicious uncertainty. Essentially, it’s all about getting the learner into a sweet spot that comes from being challenged just enough.

I use this conceptual model regularly in my coaching to ensure that my clients steadily progress in their development. Good leaders know how to get their employees going. It’s a subtle skill that isn’t always easy to put into practice. It can take a significant amount of time, trial, and error before it can be used correctly, but in the end, when the employee is regularly operating in their ideal learning zone, their development can skyrocket, and all the effort to get to this place can be rewarded.

Are you disciplined?

Five birds are perched on an electric wire and all of them decide to fly away. How many are left? Five. They decided to leave but didn’t actually do it!

Do you see yourself in this joke?

Everyone is looking to improve in one area or another. But there’s a difference between deciding to do something and actually doing it. Many people fail because they simply aren’t able to apply the required discipline. You’re not alone.

Discipline is the state of mind that motivates us to perform a series of tasks, even if we don’t feel like doing them. It’s the mental strength required to tackle mundane or difficult tasks because we know they’re key to our success.

The ability to perform optimally on demand is fairly rare. In fact, becoming an elite in any field is rather uncommon. To reach the top, you have to go about things differently, look to distinguish yourself, and be ready to do more than others in your field. The same rule applies whether you’re an Olympic athlete, an engineer, a teacher, or an administrative assistant.

As a mental coach, my mandate is to help the best athletes in the world to thrive. My philosophy is that if you work with high performers, you need to be a high performer yourself. The way I see it, I don’t deserve to work with these incredible human beings if I don’t push myself to be the best I can be. Otherwise, what credibility would I have when I ask these athletes to push their limits if I don’t challenge myself?

My mission for the PyeongChang 2018 Olympic Games in South Korea was to help the athletes win gold medals. It was as simple as that. I had plenty of time to think about this mission during my fifteen-hour flight to Seoul!

People who go to the Olympic Games will tell you that it’s like running a marathon. It’s true. I was in PyeongChang for twenty-four days, coaching seven athletes competing in five different sports, with no days off. Half of them were competing in the mountains, and the other half in the city. I had to switch accommodations five times so that I could be close to the athletes and coaches.

At home, I work four days a week and enjoy long weekends to spend time with family and friends, get some extra rest, and do my favorite hobbies. In PyeongChang, I had to be on all the time in a continuously changing environment with the pressure at its pinnacle, given the magnitude of the Olympic Games.

During the last few weeks leading up to the Games, I reminded myself that if the athletes had to be perfectly prepared, I did, too. So, I decided to purposefully go to bed early several nights a week to accumulate some additional rest. I also drew up a specific game plan in anticipation of the twenty-four-day marathon.

Upon arrival, I put my game plan into action with intense discipline. I was in the gym at 6:00 every morning. All my meals were planned to provide my body with the energy it needed until bedtime. I took time every day after lunch to nap or meditate — me time that allowed me to recover from the morning’s fatigue and build up stamina for the rest of the day. I made sure to get my beauty sleep every night. I was on a mission.

There were moments when I found my game plan to be routine and rigid. How many times did I resist the temptation to go to bed later so that I could cheer on Canadian athletes competing in other sports? After all, I was at the Olympics, wasn’t I? Not to mention the times I would have willingly swapped my balanced meals for more delicious comfort food options. Try resisting the tempting smell of burgers when you walk next to the Golden Arches three times a day. Yes, you guessed it: there was a McDonald’s in the Olympic cafeteria. Not cool for the athletes’ menus, eh? But what can you do? The Olympics have a large appetite for sponsorship money. Each time the temptation would arise, I would go back to the heart of the matter: Why are you here, JF? To help the athletes achieve their dreams. This short reminder was enough to bring me back to my mission.

In hindsight, I’m convinced that this robust discipline played a key role in helping me do my job at a high level throughout the Games. I was able to maintain my upbeat energy, be attentive to the athletes’ needs, and stay focused during the entire run. I never crashed.

The athletes I was coaching won several medals. What impact did my performance have on these results? We’ll never know. What I do know, though, is that I offered the best version of myself.

My performance in PyeongChang was based on a few of the important factors mentioned in Chapter 1:

- I chose to be my own teacher (student of the game) thanks to a well-thought-out preparation plan that I executed to a T.

- I drew a lot from previous eventful experiences courtesy of the Rio Games in 2016.

- I arrived in South Korea with clear intentions and daily reminders to stay focused.

- I provided myself with the means to remain balanced. My table had four very sturdy legs.

Seize every opportunity to learn. Be proactive. If you become the master of your own progress, you’ll become an Olympian at whatever your area of expertise.

In the following chapters, we’ll discuss several concepts that will help you perform on demand, deal with complex situations, believe in your own abilities, and remain calm under pressure.