3

On My Own

WHEN I GOT OUT of high school, I went to work for a ranch near Harrison, Montana, a cow/calf outfit that produced about five hundred calves a year. I spent the better part of that first summer building and patching fences and irrigating.

The rancher wasn’t as interested in riding as he was in farming, but he did have two colts, and he asked me to start them for him. It was just what I wanted to do, so in my mind two seemed like two hundred. Otherwise, it wasn’t much of a job, but I needed it badly.

I hadn’t had much formal training working with young horses back then. The day I started, I got one of the colts saddled up, led him into the corral, and just tied him to the fence. Now, when a colt wants to buck, you can see it coming, and this little guy really wanted to buck. I thought, Well, I’ll just get on and off him a few times while I’ve got him tied to the fence, so at least I’ve got a fair chance when I turn him loose.

And that’s when things fell apart. The moment I got on the colt, he pulled back and bucked forward. We had a hell of a time, and then I’d peel myself off. After a little bit of this, I was sitting there thinking things were going pretty well. I was enjoying the elevated view when the colt pulled back again and broke the halter rope six inches from the halter.

If that happened to me today, I would be in a six-foot-tall round corral, from which it would be hard for a horse to escape. On that day, however, the only thing I had surrounding me was a hog-wire fence about four feet high. The ranch didn’t have a round corral or an arena or anything like it, just a hog pen.

There are moments in life where certain odd thoughts go through your mind, and this was one of them. The sun wasn’t quite up yet, but that sky was a bright blue. I remember thinking how pretty it was. Then, after a nanosecond of stillness, off went the colt bucking and kicking with me pulling leather for everything I was worth.

The colt jumped the hog-pen fence and bucked out into the adjoining pasture. He’d run and buck, and there wasn’t a thing I could do but just try to stay on him. I knew if I tried to get off at this point, I was going to get hurt.

I don’t know how long I was out there. It was my first time ever riding a horse without reins, and it seemed as if it went on for hours. He’d stop and stand frozen, and every time I’d try to get him to move he’d go to bucking again. We were maybe a mile and a half from the house by the time I got him to move without bucking, but I couldn’t direct him because I didn’t have a halter rope to work with, so I just kept him moving.

In my wisdom of all of eighteen years, I figured that eventually the colt would want to go home. I kept working him with leg pressure and eventually we ended up back at the barn. My dismount was more like a bailout, but we made it back in one piece.

I’d like to think that skill has prevented me from getting hurt many times in my life, but luck doesn’t hurt either.

An important ranch chore is putting up hay. That means you cut it, ready it to be baled, and then you stack the bales. Real summer fun in cow country.

One day I was driving a swather, a machine for mowing hay. All I’d ever wanted to be was a cowboy, so I didn’t really want to be driving machinery and putting up hay. Still, when the boss pointed out a field and said, “Mow it,” that’s what I did.

The swather unit was not in the best shape. The drivers, which are similar to a car’s transmission, slipped. You could run it on level ground, but the problem became amplified when you had to work a hill, of which the ranch had many.

I got up on top of one of the hills, but I hadn’t been informed that it was a piece of hay meadow that was never cut. That’s because it was too steep; the bottom of the hill dropped off about six feet and into a swamp.

My heart started pounding pretty hard when I saw the lay of the terrain in front of me. I was a little afraid of the machinery, but I figured my boss knew what he’d gotten me into, so I tipped the swather off over the hill.

What followed was another one of those moments where time stands still. After a brief moment of peace with the cornflower blue sky above, off I went downhill, going faster by the moment.

I did what I might have done with a runaway colt: I tried to pull his head around. I pulled back on one of the control levers real hard, which resulted in what looked like one of those Saturday-morning cartoon wrecks. I had stacked this machine up in the middle of a wheel-line irrigation system. Everything was wrecked: the irrigation system and the swather. It was a mess.

I got out of the swather and stood there reviewing the results of my labor for the morning. A momentary quiet graced the earth, and all was at peace. Then I started walking back toward the ranch headquarters.

As I walked by the shop, the boss asked where I was going.

“Going to the house,” I said, still walking.

He asked what had happened.

“Well, we had a little accident.”

He looked at me for a minute and asked, “What did you do?”

I looked at the ground for another minute, and replied, “Well, just had a little wreck.”

His expression changed. “Where’s the swather?”

“It’s in the field,” I said.

“What did you do?” He was starting to get a little touchy now.

I paused a minute and looked him square in the eye. “I wrecked it.”

He kind of slumped as he realized what was next, and said, “Well, you can just go to the house, and you can pack your—”

“I’m already there,” I said.

I was fired, and I can’t blame him. I was costing him a lot of money, ruining his equipment. But maybe if I hadn’t been fired, I might have quit, anyway. For some reason I’d known that that was kind of the end of the deal.

Besides, it was the end of the summer, and the work was about over. I’d been talking to an outfit over by Three Forks, Montana. It was called the Madison River Cattle Company, and it had a lot of cattle and it raised horses. It was my kind of place. I was definitely on my way to becoming a cowboy.

When I went to meet with the ranch manager and talk about a job, he was in town at a Ray Hunt clinic. A teacher in high school had told me about Hunt and the wonderful things he could do with a horse. I thought that was just a made-up story and said, “Ah, he doesn’t have anything he can teach me.”

The teacher had replied, “If you ever want to see how the pros do it, you need to look him up.” Mrs. Jackson wasn’t going to argue with me. I was about at the age where I knew everything about everything, and the teacher was smart enough to know there wasn’t any point in saying any more.

I headed into town to visit with the manager and see just what this Ray Hunt clinic was all about. I arrived at the arena and took a seat at the top of the grandstand, but there wasn’t much going on. It was lunchtime, and I couldn’t find the ranch manager.

I was getting up to leave when into the arena came Ray Hunt and Tom Dorrance, another legendary horseman. They started working with their horses, and all of a sudden I noticed some things that Ray Hunt’s saddle horse was doing that I didn’t know a horse could do, moving from side to side and bending and backing with no visible effort from the rider.

I moved down closer to the action, and closer again until I was standing right by the round corral. I peeked through the rails and watched Ray’s every move. I just couldn’t believe it. I never knew a horseman could be that good. And, of course, Tom Dorrance was there helping Ray in the clinic and also doing some things that I thought were just magical.

Ray started working with a young broncy horse that wanted to strike out. In my experience you saddled such a horse by tying up a hind leg to immobilize him so you could get the saddle on him. But Ray worked the colt at the end of a rope, moving the colt’s hindquarters right and left and the forequarters right and left, basically teaching the horse to dance. Ray already knew the theory behind the dance: when you control a horse’s feet, you also can control that the horse doesn’t move unless and until you ask him to.

By the time Ray had that colt saddled, I said to myself, “There’s really something going on there.” I knew I’d have had a hard time saddling that colt, and I was a good hand with horses.

That was the first time I ever saw a person work a horse that way, using his understanding of a horse’s mind and body to train with kindness and to end up getting some of the sharpest turns and hardest stops I’d ever seen. And all with a plain snaffle bit. What’s more, the horse looked happy, as if he enjoyed being with the man. His expression showed contentment in his eyes.

Seeing Ray Hunt in action was just a brief encounter, but it impressed me no end.

The ranch manager saw me and came over. “I guess you want to talk about that cowboying job on the ranch?” he said.

“Sir, I would,” I told him. “But if you’d excuse me, I’m trying to watch this gentleman work horses. So if it’s okay with you, we’re going to have to talk a little later.”

Well, that kind of took him aback some. We didn’t really visit that afternoon, but we had other chances because I returned for the rest of the Ray Hunt clinic. I was hooked for life. To this day I’m still trying to pursue the magic that I saw that man do.

I got the job at the Madison River Cattle Company. The manager took quite an interest in me and started sending me to Ray Hunt clinics. Ray Hunt gives the initial impression of being the most secure, unaffected person you’d ever meet. The things he taught me about horses and the things he’s taught me about myself have changed my life. The approach that he has to working with horses was like nothing I’d ever seen, nor probably ever will see again. He’s a great horseman, and a fine gentleman. I admired him so much that I wanted nothing more than to be just like him. He and his wife, Carolyn, have been like parents to me. They have treated me like family through the years, and for that I’ll forever be indebted to them.

When I showed up at the ranch a few days after the clinic, the cow boss, Mel, showed me the bunkhouse and the cookhouse. When we sat down for dinner, he said, “We’re going to be gathering cattle tomorrow. If you like, you might want to catch that roan horse out there. That’s going to be one of your horses; the whole pen of horses is going to be your string. Some of the other boys have had a little trouble with them, but you shouldn’t have any problem, although you might want to ride him around the corral and get some of the kinks out of him before we go gather. It’s pretty rough country.”

I thought, Sure, no problem.

So after dinner, I went out and ran the little roan horse into the round corral. I had to rope him as he was a little broncy, but I thought, Well, no big deal. I got him saddled up with no trouble. I didn’t know anything about groundwork or getting a horse loosened up or relaxed. I thought I’d just step up on him.

Well, that horse bucked so hard, he bucked my hat clear out of the corral. I stayed on him, but by the time he was finished bucking, I felt as if I’d experienced a seizure. “What have I gotten myself into?” I asked myself when I stopped shaking.

The next morning we saddled the horses in the barn, then hauled them about thirty miles in a truck and trailer up into the hills where the cattle were. After we arrived, Mel said, “Here, let me help you get that roan horse ready.”

Back in those days Mel knew just enough about Ray Hunt’s techniques to be dangerous. He was working the horse on the end of the halter rope from his saddle horse, and he told me, “Go ahead, Buck, get on. I’ve got you snubbed up”—snubbed up meaning he had a hold of the horse—“so you won’t have any problem with him bucking. I’ll just dally up, and it’ll shut him down.” That meant he would wrap the rope around his saddle horn; the confinement would keep the roan under control.

Not quite. As soon as I climbed on, Roany started bucking. It seemed as if he bucked in four directions at the same time. Every time I’d just about get in sync with his bucking in a straight line, Mel would ride off and jerk his head around. That sent him off in another direction, which made it ten times harder to ride. I’d have been better off if Roany had broken the halter and gotten away. Then at least he’d have bucked in a straight line.

I was a dishrag when Roany decided to quit bucking. Mel took off at a trot on a long uphill grade. I had enough experience to know that if I was going to survive the day, I needed to get Roany out of breath. We trotted what seemed like six miles up the grade until we got to the top, but Roany hadn’t even broken a sweat.

Mel halted and let his horse rest. He was looking for cattle through his binoculars and having a nice break. I was getting a little nervous with Roany standing around catching his own breath, and I thought, Come on, Mel, let’s keep moving.

On a normal day you might think, Ah, the sweet smell of sage on a frosty clear morning. Wrong-o. All I could smell was nervous sweat. And as Roany’s respiration began to slow, mine sped up in anticipation of the next move in our dance together. Mel kept looking and looking. Because I was new on the job, I didn’t want to say, “Mel, I need to get the hell out of here and get going.” I was sitting very still, trying to convince Roany that nobody was on his back.

Finally, about the time Mel was ready to go, Roany took a big old deep breath. His respiration returned to normal. His batteries were recharged. We tipped off the hill and hadn’t gone two steps before Roany started bucking. And I mean bucking. The hill was steep enough so that he was clearing about fifty feet at a jump. As Mel cheered me on, Roany and I bucked all the way to the bottom.

I learned my lesson about the dangers of standing still, of not having my horse’s legs under my control. For the rest of the day, we stayed at a high trot, and I survived it, even with Roany bucking all day long.

Roany was quite a project for me. The first hundred days I rode him, he bucked every single day. After a few months, however, I wised up and started spending some time around Ray Hunt. Thanks to the techniques I learned about hooking on and getting a horse to move his feet, Roany gradually improved. I finally got him to the point that I could swing a rope on him and get some ranch work done.

One day we were up in that same country where we’d been gathering cattle that first day. Roany had stopped bucking and was serious about his work, but being a kid, I couldn’t leave well enough alone.

I was bored because there weren’t any cattle to rope at the moment. I wanted to rope something, so I roped a little tiny sagebrush about the size of a small potted plant. I dallied off and pulled it up out of the ground. Little did I realize that this tiny piece of sagebrush had roots about thirty feet long. I pulled and I pulled, and the rope was stretched to twice its length when that little piece of sagebrush finally came loose and flew right up under Roany’s tail.

Roany clamped his tail down so tight that you couldn’t have pulled that sagebrush out with a pickup truck. And off he went. He didn’t buck me off, but he used me plumb up. Plus that little stunt of mine probably set me back a few weeks in his training. I had been really getting somewhere, and then I pulled a trick like that. I learned another valuable lesson that day, that time about me.

The day came when Roany was sold. I knew it was coming. We raised horses to sell, but Roany and I had been through a lot together, and it was a sad day for me. All I could think about were the times on the way to the barn that I’d say, “God, give me one more ride with Roany. Just don’t let him kill me today.” The next day I’d say, “God, I know I said I wouldn’t ask for anything else yesterday, but it’s me again.” Then we got to be partners, and pulling my saddle off him in the sales ring made me sad to see him go out the door and off to a new life with a new owner.

An old man who lived near Deer Lodge, Montana, bought Roany. He roped steers on him and used him on the ranch the rest of his life. They got along great. Roany had a good home, and I’m glad because he was an important milestone in my career: he was the one I was going through hell with about the time I first was exposed to the kind of riding I do today.

Another memorable lesson during my time at the Madison River Cattle Company came when I was working with a very troubled horse named Ayatollah. Needless to say, like his namesake, he was a bit of a terrorist: we’d been through quite a few bronco rides. Ayatollah would buck you off if you cleared your throat, so you didn’t have to do very much to get yourself into trouble.

I’d been trying to get him to do a turnaround, a move where the horse brings his front feet across while pivoting on a hind foot. It’s a quick and efficient way to move away from something fearful and a very natural movement for a horse in the wild, but encouraging a horse to turn around while you’re sitting on his back can be a bit tricky.

One day, I was watching Ray Hunt do a demonstration at the indoor arena at Montana State University. A couple of guys had brought him a colt that was kind of a setup; they wanted to make Ray look bad because he was pretty controversial in those days. People thought that the notion of getting along with a horse, communicating with the horse, and even, God forbid, being friends with a horse was forsaking the western image of being a cowboy.

Out came the horse, a five-year-old black stud colt. Both ears were frozen off, and his mane and tail were full of burrs. A real pitiful-looking animal, and touchy, too. The two old boys herded their horse into a round corral that had been set up in an indoor arena, then they waited with smirks on their faces. They just knew they were going to get that old man—Ray was in his fifties—in a wreck.

Ray knew he was being set up, so he told the owners, “I can see you take a lot of pride in your horses. I know you have a bright future for this colt, so I guess I’d better get him leading.” Ray, who had been born with a clubfoot, kind of limped into the corral. A few minutes inside, and he could tell he wouldn’t be safe on foot, so got up on a saddle horse.

Using patience and skill, in under ten minutes Ray had the colt leading and standing right beside the saddle horse so Ray could rub him with his rope’s coils.

Within another five minutes, Ray had the colt saddled. But when he turned the colt loose, everything came undone. The colt bucked and kicked, the stirrups hitting on his back at every jump.

Ray, who was then on foot in the corral, kept the colt moving around. He threw a rope around the colt’s neck, then led the horse up to him and petted him down the forehead. Turning to the owners, he said, “I don’t want to hold up you boys’ progress, so I’d just better ride him.”

By now these guys were thinking that maybe they’d set up the wrong man, but they were still fairly confident because Ray still had to get the colt ridden.

The colt had the rope around his neck. Ray looped a part of the rope across the colt’s nose to get him bending toward him, pulled down the stampede string of his hat and tucked it under his chin, and stepped onto the colt.

Ray was wearing a down coat, the kind that makes more noise than you’d want to be making on a young sensitive colt. He unzipped the coat and slipped out of it. With his rope in one hand and the coat in the other, Ray reached back and tapped the colt on both hips.

Everyone watching waited for the explosion, but the colt just loped off like the gentlest son-of-a-buck you ever threw a leg over.

Ray allowed the horse to stop, and then said to the men, “Well, considering how far you boys plan to take your colt, I’m sure you’d like him to turn around a bit.” With that, Ray reached forward with his coat, and the horse turned.

Turned? The colt spun so fast he was a blur. I don’t know how Ray’s hat stayed on his head, even with the stampede string under his chin.

Ray then shook the rope in his other hand, and the colt spun the other way. With that, Ray loped the horse around the corral, through the gate, and continued to lope around the indoor arena. While he was at it, he asked the colt to make three or four lead changes. The colt obliged, and with beautiful clean changes, too.

Then Ray galloped the colt down to where its owners were standing—and I mean galloped—ending with the most beautiful sliding stop you ever saw.

Ray flipped the loop of the rope over the colt’s nose, stepped down, and offered the rope to the men. “Well, boys, I guess I got him ready for you,” he said.

One of the guys started to reach out, then pulled his hand back as if from a hot branding iron. “No, Ray,” he said, “I think the horse has had enough for the day.”

Ray looked the guys in the eye and replied, “Well, boys, I don’t know whether you got what you came for, but this horse did.”

I couldn’t wait to try this new way of turning out on Ayatollah. When I got home, I hung my coat on top of the round pen fence where I could reach it from horseback. Then I caught Ayatollah.

When I got him saddled, he was walking-on-eggs edgy. As we tiptoed around the corral, I got closer and closer to my coat, and when I was close enough I grabbed it. He didn’t explode, but that hump in his back was so big it looked as if I had left my lunch under the saddle blanket.

Finally, the time came for me to work on the turnaround. I stuck my coat in Ayatollah’s face, and he turned so fast everything was just a blur. I didn’t realize the centrifugal force of a turning horse could be that strong. I was losing count of the turns he made when suddenly I was flying off the front of him. I’d have hit the ground if my left spur hadn’t hung up on the back of my saddle.

I found myself looking right into his eyes, and he was as terrified as I was. Dropping the coat never crossed my mind; absolute terror had taken over my entire body, and my hands were paralyzed into clenched fists. The longer I held the coat out there, the harder he spun.

Ayatollah was spinning and spinning and spinning, and he wouldn’t stop. Although I knew full well that if I could somehow get off him that he would probably kick me before I hit the ground, I decided to do what I could to free my spur from the cantle and take my chances.

When I finally kicked loose, Ayatollah drove my head into the ground at what felt like a hundred miles an hour. My lower jaw plowed up maybe two pounds of dirt and manure. What I didn’t plow up with my lower jaw, I scooped up with my belt buckle, so the rest of that dirt and manure went down my pants.

Just as I slammed into the ground like a lawn dart, Ayatollah did indeed kick out at me. His right hind foot landed on my right ear. He didn’t kick me in the head, but my ear swelled up about as big as a mitten.

As I lay on the ground with Ayatollah bucking around the corral, I remembered one small detail (evidently that bump on my head jogged loose a little memory I should have drawn on prior to getting on Ayatollah): when Ray Hunt did the spins, he reached back with the hand that didn’t have a coat in it and held on to the Cheyenne roll on the cantle of his saddle. That kept him from going over the front of his horse when he started to turn.

That was quite an important point, and I learned it well. The next time I attempted to turn Ayatollah with my coat, I gave him a very measured, very small, portion of coat, and I gave myself a very large portion of Cheyenne roll to cling to with my free hand. The turns worked out a lot better, and since then I’ve never had to remind myself about preparing for the consequences of a fast turn.

That lesson was better than any clinic I could have gone to.

After I left the Madison River Cattle Company in 1982, I went to work for a horse outfit near Bozeman. I had been doing things my teachers had shown me, but I’d also seen that this gentle approach to working horses still had quite a bit of opposition. People were real apt to hang on to their old ways and not try anything new. These days, what I do with horses is very popular, but it sure wasn’t back then.

I was taking morning classes at Montana State University in Bozeman and then going back to the outfit to ride colts in the afternoon. I didn’t ride the owner’s colts, though. He had hired other trainers for them, and those guys had their own ideas.

In the barn one day after class, I saw the owner and one of his trainers trying to halterbreak a filly. They had led the filly and her mare into a stall, jammed the filly into a corner, and muscled the halter over her head any way they could. Then they led the mare out toward a fence, and when the filly followed, they tied her to a post and led the mare away.

You can imagine the wreck that resulted. The little filly had absolutely no preparation for standing, so naturally she pulled back and fought. She struck out with her feet, and she flipped over. By the time I arrived, she had been upside down who knows how many times. Now two grown men were stomping on her head, kicking her in the belly, and beating her with the metal bull snaps on their halter ropes. When that didn’t work, one of them poured a bucket of water into her ears to try to get her to stand up. The filly did get up, but then she’d fight again and fall back down.

The filly was insane with fear. She jumped up, but as soon as she felt that tight halter rope, she flipped over again and got hung upside down by her head. If you’ve ever heard young horses in agony make a certain pitiful, desperate sound just before they die, that’s the sound she was making. I shuddered to imagine what it was like for her mother to hear that from a distance and not be able to do a thing about it.

The next thing I knew, these two brain surgeons were dragging a hose toward her. They were going to douse her real hard to try to get her up and then keep her on her feet.

I had stayed out of their way until now. They had mocked my way of working with horses. Even though I had more than once bailed them out by helping them with trailer loading, they had dismissed everything I had done for them. But when I saw they were planning to hose water down the filly’s ears, I couldn’t stand it any longer. I unsnapped the lead rope so the filly could get her head down, then I snapped another lead shank to the halter.

It didn’t take me more than a few seconds of gentle persuasion to get her up. I rubbed on her forehead for a moment or two, and in less than five minutes I had her leading all over the arena.

These two supposed horse trainers should have been embarrassed or ashamed, but they were so overcome with anger, they weren’t able or chose not to see what they had done to this little filly. And they were upset that I had succeeded.

I led the filly back to one of the men, the one who owned the operation, and handed him the lead rope. I looked him right in the eye and didn’t say a word. I didn’t have to. He saw my anger and resentment.

I rolled up my bed, and when he woke up the next morning, I was long gone. There was no way I was going to change him, and I certainly wasn’t going to be around that kind of behavior. I moved to Gallatin Gateway, to another indoor arena up the Gallatin Canyon at Spanish Creek.

While I was making a living riding colts, I was also pursuing my roping. After Smokie and I had moved in with the Shirleys, our trick-roping careers had ground to a halt. Betsy and Forrest knew nothing about the rodeo business, especially how to promote us as Dad had done. In my junior year in high school, one of my teachers asked me to play Santa Claus and do rope tricks in the Christmas play. I hadn’t spun a rope in a while, at least not in a show, but I said I would and started to practice. Everybody in the little town of Harrison was in the school gym that evening, and when I finished, I got a standing ovation.

I kept on practicing a minimum of three hours a day, seven days a week, even long after I got out of high school. Three years later, after I was reinstated in the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association (my membership had lapsed), I got good enough at the Texas Skip to set a world record by hopping in and out of the loop 980 jumps in a row. This record was later shattered by my friend Vince Bruce, an Englishman who did something like two or three thousand jumps.

Thanks to the Santa Claus skit, the show-business bug had taken ahold, and just about the time I got back into the PRCA, I became involved with the State Department’s Friendship Force. That led to travel as a part-time goodwill ambassador helping promote U.S. tourism. My first trip was to Japan as part of a group that included a number of Native American dancers, some country-and-western musicians, and the 1980 Miss Montana, Wendy Holton. The Japanese loved cowboys, and there I was, eighteen years old, now over six feet tall, with blond hair, surrounded by beautiful Japanese girls, and keeping company with Miss Montana. I was about as close to being John Wayne as I was ever going to get, and when the tour was over, I really didn’t want to leave.

Buck on an international tour with the Friendship Force, spinning ropes for the local media in Newcastle, England.

My stint with the Friendship Force convinced me there was no reason I couldn’t make a good living doing rope tricks. I put what money I had together and took off for Denver and the big stock show held there every year.

The rodeo producers held a convention at the Brown Palace Hotel, where you went to get your jobs for the year. You promoted yourself by renting a booth and putting up a little display. Because my dad had always handled that part of the business, I knew very little about it. I hadn’t realized there was a lot more needed than just being a good trick roper, so I wasn’t prepared at all.

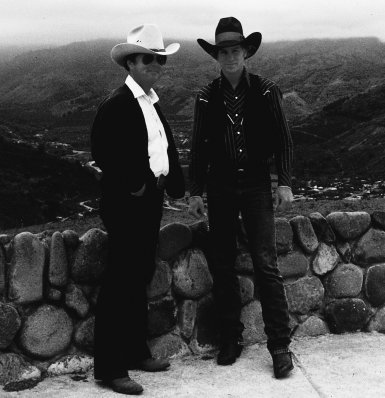

Buck in Costa Rica with Mike Thomas, manager of the Madison River Cattle Company.

I spent most of what little money I had on a hotel room, and most of the rest for booth space, but I had nothing to put on the booth. A friend named Doug Deter helped me take some pictures out in the snow, and we put them on a poster board and tried to make some sort of a display. In addition, I had some pictures in a photo album that showed some of my rope tricks, but on the whole it was a pretty sorry presentation.

I sat for three days and watched the rodeo producers walk by and stop at the other booths. Every producer had a little contract book, and I saw contracts being signed right and left. It seemed as if everybody was signing contracts, but by the third and last day of the convention, I hadn’t signed a single one. All the money I had saved up was gone, and I had no prospects. Although I was really a good trick roper, probably the best one there, no one knew.

Every day at 4:00 P.M. was happy hour, when the convention committee members passed out free booze and everybody joked, laughed, and told stories. During happy hour on the last day, a very influential rodeo producer passed my booth.

Forcing myself to summon up the courage to speak with him, I stopped him and asked, “Sir, would you take a moment and look at my album in case you would ever want someone to do some rope tricks at one of your rodeos?”

He just looked at me and said, “Son, I’ve looked at so goddamn many pictures today, I don’t care if I look at another one.”

“Well, I’m committed now,” I told myself, then practically begged him to look at my pictures.

The producer didn’t sit down. Instead, he just flopped my album open on a table in somebody else’s booth and started flipping through the pages. He never looked at a single one. He was laughing, joking, and greeting people across the room.

Buck practicing his roping around the time he was looking for rodeo work.

When he spilled his drink in the middle of my book, I took it away, slammed it shut, and said, “Thanks for your time.”

He just glanced at me. He didn’t say anything. What happened to me meant nothing to him. As you can imagine, happy hour wasn’t so happy for me. I went upstairs to my room, threw down my photo album, lay on my bed, and cried. Nobody cared.

I went back to ranching and really thought about quitting rope tricks. I had a good cowboying job, but I had no roping jobs and no prospects.

Later on that summer a rodeo contractor named Roy Hunnicut out in Colorado called me. He said, “Son, I’d like to hire you to do some rope tricks for me in a few rodeos. A guy who was trick riding for me broke his leg. You’re the only one who’s not working. I want to give you a try at one in Rock Springs, Wyoming. If I like what you’re doing, I’ll give you the rest of my rodeos.”

The manager of the ranch where I was working was happy for me. “As long as you come back in time to get the colts ready for the fall sale,” he told me, “you go ahead and hit some of these rodeos.”

I drove all night to get to Rock Springs for the Red Desert Roundup Rodeo. I didn’t have much of a fancy truck, trailer, or horses. In fact, my old horse trailer featured a variety of spreading rust motifs by way of decoration. But I had some damn good rope tricks.

There were five or six thousand people in the audience. I did my best stuff, and it brought the house down. I got a standing ovation.

Since I hadn’t been sure whether Hunnicut would take me on for the rest of the season, I had left some of my stuff back in Montana. A friend named Bob Donaldson had asked me to give him a ride to Douglas, Wyoming, on my way back to pick up my things. Bob, who was working the high school rodeo finals there, offered to introduce me to the producer of that event. He said, “I think he’d really like to talk to you. He’s heard that your rope tricks are really good, and he really wants to give you a job. He could be a great connection for you.” I knew who the man was but I didn’t say a word.

When we got to Douglas early the next morning, this big-time producer was sitting around and drinking coffee with a bunch of his cronies. Bob introduced me to him, but the rodeo producer didn’t recognize me. Of course he didn’t; he had been too full of himself that afternoon in Denver.

He said, “Well, I’m so-and-so, and I’ve got a lot of big shows, some of the biggest rodeos in the business, and I heard you’re really a hell of a performer. I’d like to give you some work, son.”

I replied, “Well, sir, I know you don’t remember me, but I certainly remember you. And it’s not that I don’t need the work, because I do. But working for you and going to those big rodeos wouldn’t mean near as much to me as telling you to kiss my ass. You still don’t remember me, and it doesn’t matter. But because of what you did to me at one of the lowest points of my life, I’ll never forget you. It’s people like you who are going to make me successful one day.”

Thanks to Roy Hunnicutt, I had plenty of success with my rope tricks, if you want to call it that. I was good at them, but it was kind of a dead-end deal. I was lucky to make $200 a performance, and by the time I’d paid my expenses, I was making less money than cowboying for $450 a month. Besides, I had a lot better time on the ranch than I did on the rodeo circuit—the loneliness of being on the road got to me, too, so after a few years, I went home to the ranch.

However, I’ve never forgotten the impression that “big-time” rodeo producer made on me. He wouldn’t give me his time because he didn’t figure I could do anything for him. He didn’t respect me as a person. That was a good lesson I’ve never forgotten.

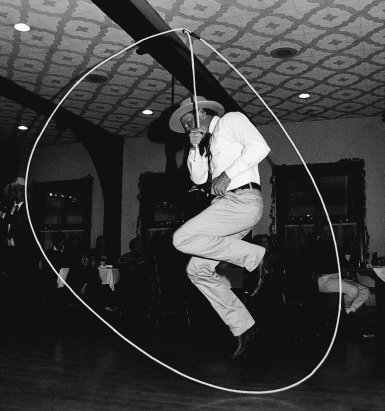

Always up for a good cause, Buck does the Texas Skip at a benefit for the Sheridan Inn in Sheridan, Wyoming.

Now that I’ve reached the point where I have a certain amount of influence, I try real hard to take time out for people who may expect not to be noticed. If somebody writes me a letter or comes up and talks to me, I appreciate the courage the effort may have taken, and I try to give them my time. I try to learn their names.

It hasn’t been that long since I was in their position.