6

Welfare

ONE OF THE MOST INTERESTING and important horses in my life was named Bif.

He came into my life during the summer of 1988. I was in despair over the ending of my first marriage, and I had been looking for months for ways to save myself. Once I started working with Bif, however, things began to look up. He was an important turning point in my life, and I damn sure was in his.

Because Bif was a dangerous horse to be around—he was lethal with his feet—I had to put so much of myself into working with him, not just to succeed, but to survive. It was hard to figure at the time, but Bif was quite a gift to me, all part of the healing process. He was also a validation of the approach to training horses that I had become associated with.

I named him Bif after Marty McFly’s nemesis in Back to the Future, a popular movie at the time. The movie Bif was a big, tough, violent sort of person. (“Bif” was also an acronym for “Big Ignorant Fool,” something my friends came up with when I started working with the horse.)

Bif had belonged to a horse outfit on the Madison River in Montana, an outfit that had a reputation for raising tough horses, broncs that tended to have problems with people. Rodeo stock contractors who knew about the horses figured anything with that outfit’s brand had a pretty good chance of making a good bucking horse, a real draw at rodeos.

I was working on the other side of the river at the time, and I had been watching the outfit’s cavvy of horses for several weeks. Bif stood out from the bunch. He was a big red thoroughbred-type Quarter Horse, and I knew he had some age on him—he looked to be four, maybe five years old. I needed a good gelding for the clinics I gave, so one day I rode across the Madison for a closer look.

The horse had a head that only a mother could love, and then only with a little effort. I could see he was pretty troubled and pretty scared. And I knew the reason why.

The folks who owned him had their own way to halterbreak their horses. They’d put them in tie stalls and manhandle the halters on. This wasn’t too hard to do when the horses were babies and were in tie stalls that measured only twelve by twelve feet. Then the horses would be kept tied up and away from food or water, sometimes for long periods of time, so that when they were untied, the young horses would readily lead to the stream to drink.

Even though the people had the best of intentions, the treatment was rough, and what came next was worse. Instead of teaching the horse how to give to pressure, one man would pull on his head as another one whipped him from behind. That’s because the people thought the horse would associate getting a drink of water with leading. I don’t know which brain trust thought this up, but it lacked a little in the logic department, not to mention how unkind it was.

You can only imagine the wrecks that resulted. Some horses couldn’t handle the pressure, and when they’d try to pull away, they’d flip over backward. They’d begin kicking and striking and biting at the rope, with their ears pinned back.

Unfortunately, a lot of people still use this primitive method. They muscle their horses around and give “cowboys” a bad name.

Bif had been “trained” to lead this way. He’d also been branded and castrated during this time. Everything that had been done to him had been negative, and as far as he was concerned, humans were the enemy. But Bif was a survivor. His spirit didn’t bend, and so rather than work with him, the horse handlers simply turned him out to pasture for a long period of time. This was a bad move all around. It meant he got to dwell on his negative exposure to humans.

That was the way Bif came back in from pasture when I met him. I could tell that he’d pretty much decided nothing like his past was ever going to happen to him again. But I still liked what I saw, and, after some thought, I bit the bullet and made the deal to buy him. I basically paid what is called “canner price,” what the dog-food people would have paid.

The folks in the outfit ran him into a big pen, and I rode in on my saddle horse and roped him. I thought I’d try to lead him into the horse trailer, but at the time I didn’t realize just how unhalterbroke he was.

There was a bunch of activity as we were getting the trailer positioned, and I had Bif stopped with the rope around his neck. I needed to check on the truck, so I asked someone in the corral to hold on to Bif. “Don’t pull on him at all,” I said, “just hold the rope, and keep it from getting down in the manure.” The corrals at this outfit were really dirty, and the manure and mud were a couple of feet deep.

As soon as I started to walk away, Bif felt pressure from the rope and flipped over backward four times within about sixty seconds. It was awful. I ran back and got the rope off Bif’s head, then urged him into the trailer free, just as you would load a cow.

As I hauled Bif away, I reflected on what a potential idiot I was for getting myself into another “project.” I just couldn’t have picked a nice easy one. Oh no, I needed to prove something.

When we got home, I chased Bif into an indoor round corral. A round corral is essential to the kind of training I do because there are no corners where a horse can run and hide. A round corral allows a horse to know that there is no place he can go where he can’t move forward, no place where he can stop and lose his energy.

Bif stayed down at the west end, walking in and out of shafts of afternoon sunlight. I took a deep breath and walked toward him. Holding the tail of my halter rope, I tossed the halter harmlessly on the ground behind him. I was hoping he’d move his feet and step away, which would be a beginning. That’s because a cornered horse instinctively moves his hindquarters toward whatever is threatening his safety. He stops his feet and prepares to kick (some studs will present their front end to be able to bite as well as rear up and strike with their forefeet).

To encourage a horse to overcome this instinct, you must show him that he can move his feet forward without feeling as if he’s surrendering any of his defense mechanisms. He must also see that he can turn his head and look behind him with either eye; he needs to see you without feeling that you are going to take his life.

You then want to draw the horse’s front quarters toward you. Getting him to turn his head and look at you is the preliminary step to his hindquarters falling away so the front end can come toward you (we call that untracking the hindquarters).

Looking at you is the equivalent of shifting into neutral, presenting himself in such a way that he’s exposing his head to possible risk. You’ve not won him over yet: he’s tolerant but not accepting. It’s as though the horse still has a pistol, but he’s lowering it instead of pointing it at you. In other words, you’ve climbed a small hill. You haven’t climbed the mountain yet, but you’ve made a good start.

At this point, Bif saw me the same way he saw every other human. He figured I wanted to end his life, and he was going to make sure that didn’t happen even if it meant taking mine. So instead of stepping away from the halter, he started kicking at it. Then he started kicking at me. He’d actually run backward at me and fire with both hind feet. This was quite a sight, especially from up close.

He’d kick at me and miss, and kick some fence boards out of the corral. After a while there were splintered boards all over the place, like piles of kindling.

I spent the next ninety minutes reeling the halter in, and tossing it back at Bif’s hindquarters, trying to encourage him to move his feet forward and not be so defensive. It took that long before I got one single forward step.

After another hour and a half, Bif was taking a few steps forward, then a few more, and it wasn’t too long after that before I was driving him around the corral. That’s not to say I could walk up to him. When I did, he’d try to paw me on top of the head or kick me. He wasn’t a lover quite yet.

When working with a horse, particularly a troubled horse, you’ll notice that he will spend a good portion of his time avoiding contact, physical and mental. By causing him to move, and then moving in harmony with him, you will slowly form a connection, as if you’re dancing from a distance. Yet the horse may remain quite wary of you. When the distance between you and the horse becomes comfortable to him, you start to draw him in. You do this by moving away as he begins to acknowledge you with his eyes, ears, and concave rib cage (middle of rib cage arched away from you). At this moment you and the horse are “one.” The farther you move from him, the closer he moves to you. This is known as “hooking on,” and it’s an amazing feeling. It’s as if there is an invisible thread you’re leading the horse with, and there’s no chance of breaking it.

Before that first evening was over, after I’d spent about four hours in the corral, I finally did move up to Bif. That’s when I was able to get him to “hook on” to me. He’d turn and face me, and then he’d walk toward me with his ears up. We were now making positive physical contact. What I was doing with Bif was similar to what Forrest had done with me on the day we met, the day he gave me the buckskin gloves. He didn’t force his friendship on me. He maintained a comfortable distance until I was ready to come to him.

The experience also reminded me how much preparation and groundwork people need in order to give their horses—and themselves—a good foundation. They need to work on using the end of the lead rope to cause the front quarters and the hindquarters of their horses to move independently, whether the horse is moving forward or backward, right or left. The horse needs proper lateral flexion so that he can bend right or left while moving his feet at the same time. Horses need to be able to bend and give and yield, just as experienced dancers are able to bend and yield to their partners’ lead.

Working a horse on the end of a lead rope, you may see tightness or trepidation when you ask him to move a certain way or at a certain speed or when using his front or hindquarters. Whenever you see it, you home in on that area until the horse becomes comfortable. Then you move on to something else. Just as important, through the directional movement that you put into the end of the lead rope, you can show the horse that he can let down his defenses, that he can move without feeling troubled, without feeling that he needs to flee. Rather than leave you, he can go with you, and both of you can dance the dance. Sometimes the music plays fast, sometimes it plays slow, but you must always dance together.

As long as I did it in a way that was fitting to Bif—that is, very, very carefully—I could touch him and rub him. One little wrong move on my part, and he’d have pawed my head off or kicked me in the belly. But I had to touch him, because that established the vital physical and emotional connection between horse and human. I rubbed him with my hand and with my coiled rope along his neck, rubbing him affectionately, the way horses nuzzle each other out in a pasture and especially the reassuring, maternal way a mare bonds with her foal.

I also rubbed Bif with my rope and my hands along his back and his flanks. That not only felt good to him, but it introduced him to the pressure he would feel when the saddle was on and the cinch was tightened.

When I got Bif saddled up later that night, he put on a bucking demonstration like you’ve never seen. The stirrups were hitting together over his back with every jump. Watching him, I knew that if he bucked with me on his back, there was no way in the world I would ever be able to ride him, so I didn’t even try. I just tried to get him a little bit more comfortable with a saddle on his back, then I unsaddled him and put him up. We ended on a good note, and I wanted him to sleep on it.

I was awake all night trying to figure out how I could help this horse. The next day I repeated the process. Bif was still very defensive, but we gained ground more quickly, to the point where I could step up on him and ride.

Bif never did buck with me. On the ground, he was one of the most treacherous horses I’ve ever been around, but it was because that bunch of hairy-chested macho cowboys got him started off on the wrong foot. With horses, as with people, you get only one opportunity to make a good first impression, and they missed theirs.

For the next couple of years I hauled Biff to my clinics, but I had to make sure people didn’t get near my horse trailer. He’d have kicked or struck them before they knew they were within his range. Even if I was sitting on him, people had to keep their distance. Bif was sure of me, but he wasn’t sure of anybody else. I could ride him, but that didn’t mean he was gentle.

But for all that, whenever I’d leave Bif alone or in an unfamiliar setting, he’d whinny for me. Not the way a horse anticipates or asks for his feed or a treat, but the way an anxious horse calls out to its herd, its source of safety. Bif just didn’t want to be without me. He’d always nicker, and it became a special thing between us.

Miles together can change things, and in time Bif got a lot better around people. Now, roughly ten years later, he’s so gentle you’d never know that he had the kind of past he had. Bif’s pretty much retired. I use him on the ranch once in a while, and sometimes my little five-year-old daughter, Reata, and I take him for a ride. He’s had a good life, and he’ll always have a home with me. He’s got a heart the size of all outdoors.

Buck and Bif.

I’ll never be able to repay Bif for what he’s taught me about working with horses. He represents a lot of horses and people, too, who simply got a bad deal at the start. He proves to me that you don’t give up, and that even if you’re going through something that makes you think your life is over, you can still have a future.

I travel all over the country and get an opportunity to see lots of different people, and lots of different lifestyles and ways of doing things. All in all, I’m actually pretty optimistic about the human condition. I think of all the people who are unfortunate, who don’t have good jobs, or who are on welfare. Granted, some of these people are just lazy, and even though they could work, they won’t. Maybe they weren’t raised right, or maybe they weren’t influenced by the right set of circumstances or the right person. But there are other people who aren’t lazy and who do want good jobs, and for them, welfare can help. Some of these people prevail despite a rough start and end up with successful lives. There are Bifs all over.

I’m often asked about a welfare program for wild horses called Adopt-a-Horse. It’s been quite a hot issue in the West, where a lot of people on both sides are trying to do the right thing.

Nobody wants to see wild horses disappear from the western landscape. The activists who regard them as indigenous and want to protect them all certainly don’t. Neither do most ranchers, some of whom consider the horses to be simply feral. Although the media paints the rancher as the great Satan because he’s in favor of culling the wild herds, the rancher is not a bad person. His concern is overgrazing. He wants all animals to have enough to eat, including his cows. Most real ranchers love horses, and they love the freedom that the wild horse represents. They just don’t want to see the population become so large that the animals will starve to death.

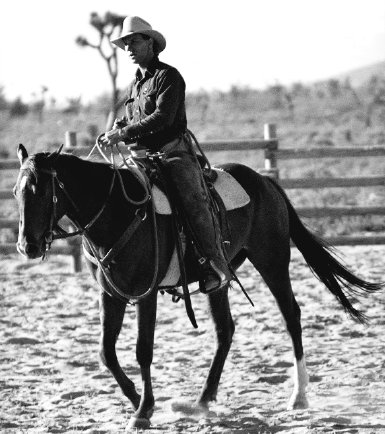

Buck shows how calmly a young sale horse responds to his “big loop” demonstration at the Dead Horse Ranch Sale in New Mexico.

In their infinite wisdom and in an attempt to resolve the issue, the Department of the Interior’s Bureau of Land Management (BLM) created the Adopt-a-Horse program. Government officials started rounding up wild horses and holding them in concentration camp–like environments called feedlots, where they were made available for adoption by anyone who wanted a horse.

The BLM thought this would satisfy both the ranchers who wanted a solution to the problem of overpopulation and overgrazing and the activists, mainly people from towns, who wanted to prevent the horses from going to slaughter.

Although the BLM was trying to do the right thing, Adopt-a-Horse didn’t work. Allowing people without any qualifications to own a horse, much less a wild one, put lives in danger. That’s an injustice to both the horse and his owner. If the horse hurts an owner, the animal gets the blame.

The BLM also created a program in which prisoners are given the opportunity to work with captive wild horses. They gentle them and get them to the point where they are ridable. This is an excellent idea. People who want to own a horse, especially those who have no experience with horses, are a whole lot safer. The horses don’t end up in a can of dog food, and the prisoners learn skills that can benefit them when they’re released. If nothing else, they’re doing something they can feel good about.

I have hope for these wild horses. They are a part of the American West that most people want to see survive. Most of you who are reading this book feel a deep-down ancient bond, a connection between yourself and horses.