9

Farther Along the Road

WE HAD TAKEN TWO TRUCKS full of horses down to Florida that winter, and we laid over in Baton Rouge for a few days’ rest. While we were there, someone arranged for me to do a free demonstration to drum up interest in clinics in that part of the country.

Angel Benton, a friend from Colorado, asked a local trainer who was in the gaited horse business to find a horse for me to work with. I guess the fellow was insecure about a stranger from out of town coming in to show how to work with horses. He must have thought, This’ll be good, and he lined up a horse.

He also didn’t keep it a secret. “Hell of a crowd, for people who don’t know me,” I said to myself when I showed up.

A gray horse waited in the round corral. Before I went in, a Cajun man took me aside said, “I don’t know you, Mr. Buck, but you watch that sum-bitch because I know him.” No one else volunteered a thing.

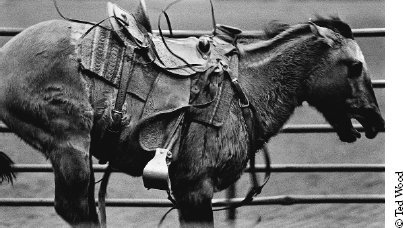

A never-before-saddled colt at the Denver Stock Show, bucking wildly after Buck saddles him. Buck allows the horse to buck and run, getting used to the saddle.

I asked what had been done with the horse. When I do that, I’m not fishing for information about the horse. I’m interested in finding out about the person or people who’ve been working with the animal. That’s because a horse’s behavior reveals as much about a person as it does about the horse. Then, too, if my well-being depended on the accuracy in reporting a horse’s background, whether intentionally or inadvertently, I’d have been dead a long time ago.

I was told the horse’s owners had tried to start him a couple of times. He bucked off lots of people, and once, when he ended up with the saddle under his belly, he went through a few fences. That didn’t surprise me. It happens all the time—it’s as common as morning coffee.

Buck approaches the same colt in a gentle and friendly way after it finishes bucking.

As I started moving the horse around the corral, I asked myself, “This is supposed to be a two-hour demonstration?” Although I knew the fellow who found the horse thought it would take only a few minutes for the horse to eliminate me, I also knew I’d have the horse ridden in no time. Then what the heck was I going to do for the two hours?

The horse bucked pretty hard when the girth was tightened, but that was the extent of the excitement. So, to fill the rest of the two hours, I came up with every trick I could think of. I led the horse by one ear, by the lip, by his tongue. I even led him by his feet.

These things are based on the unspoken but very evident draw or appeal to which another creature responds. Please note that I say “creature” because the connection works for us humans, too. For example, you can ask another person to dance, but even though you say the right words, the way you say them may not attract him or her. On the other hand, the right “feel” can be sensed across a room without a word being spoken—think of the lyrics to “Some Enchanted Evening.” The other person may have seen you and then made up his or her mind to dance the whole night with you even before you said a word.

And how do you know? You feel it. “Feel” is the spiritual part of a person’s being. There are a thousand explanations for “feel,” and they’re all correct. Horses have it, and they use it all the time. You can’t conceal anything from a horse: he’ll respond to what’s inside you—or he won’t respond at all.

I ended up the demonstration by riding the gray horse all around and then swinging a rope around him. When I had finished, I stopped the horse, who stood there hip shot (meaning he was so relaxed, his hindquarters weight rested on one hip).

I looked around at the crowd. “I know a lot of you came here to see me fail, the way lots of people go to an auto race to see bad driving, not good driving. And then there’s this boy here who lined up the horse for me.” I called him a boy because he hadn’t earned the right to be called a man. “The sad thing is he didn’t know or care what would happen if I, a stranger to him, got hurt. Or worse. I might have a family to feed or a mother to support. All to try and prove a point that seemed important to him.”

I turned to the guy. “I want to know what makes you so different from me. I say different because I can’t imagine doing such a thing. Why did you do it to someone who might be a wonderful person, someone you might have liked knowing if only you got to know him? Just what is it that makes you so different?”

Of course the guy denied knowing anything about the horse—he was just getting me a horse.

I wasn’t about to let the guy off so easy. “I’m not the only one here who knows you can’t talk your way out of this,” I said. “Now let me give you a piece of advice. You were sure this horse would eat my lunch. Well, you’re a long way from where I live. Don’t come out to my playground because we play a lot rougher out there. We have this sort of horse for breakfast. Heck, our kids have this sort for breakfast.”

Later, as I was set to leave, I noticed three Cajuns standing off to one side and looking at me. I smiled and said hello, but they turned away. The fellow who had given me the warning saw what was going on. “Mr. Buck,” he said, “those men don’t want you to think they didn’t appreciate what you did today, but they suspect you have the voodoo.”

When I replied that I had no mojo—I was just a cowboy from Montana—the man laughed. “Well, they’ll sure be happy to hear that!”

People want to know whether my approach works with other animals. It certainly does.

Hooking on with a dog is easier than with a horse. Dogs are predators, not prey. Dogs respond to food, while food training spoils a horse. It’s seldom successful in the long run. The key to hooking on with a horse is to provide comfort. Comfort means more to a herd animal than it does to a predator.

Dogs are much more trainable than cats are. Characterizing cats is a lot like a husband observing his wife or a wife her husband: cats are gratifying, interesting, perplexing, frustrating, loving … all of these things and more. You control the destiny of a relationship with a cat the same way you control it with a spouse: peaceful coexistence.

When I worked at a ranch near Harrison, Montana, a cat showed up on my porch one day. He had pinkeye, so I doctored him with the pinkeye medication we used on cattle. The cat stuck around, and I named him Kalamazoo, after a Hoyt Axton song that was popular that year. For the want of something to do, I tried to see how much I could get done with Kalamazoo. I got him so he’d lead with a string around his neck, sit down, and roll over. He’d jump in the back of the truck. He always came when called. And I accomplished all of that without using food as a reward. Kalamazoo just had the capacity and the interest to learn.

Eventually, the coyotes got him.

Much can be learned from the nobility of horses, and from how genuine and pure their thoughts are. There is no reason for a horse to look at you any differently from how he would look at any other predator. But when he learns that the two of you can go together and that going with you is better than resisting and going in the opposite direction, a feeling of comfort settles in him. His frame of mind begins to change, and he begins to view you differently.

Sometimes you’ve done your groundwork and your horse is comfortable. You get on but you’re tight, or worried. In that case, your body language is doing everything it can to get you bucked off, but your horse may remain settled even though you aren’t doing much to help him. That’s what I mean when I talk about the horse filling in for you. And filling in can be accomplished only after helping the horse gain a large amount of confidence before you step on.

Filling in comes from the horse’s being comfortable and trusting, both of which come in turn from groundwork.

People often ask, “How much groundwork do I need to do?” The answer is, enough to keep your horse and yourself out of trouble; enough to keep yourself from getting bucked off and from getting yourself and your horse in a wreck.

In other words, the amount depends entirely on how much you have to offer the horse when you get on his back. If you’re an experienced rider and can go with the motion without clashing with the horse’s energy, the amount of groundwork is a lot less than if you haven’t ridden much. If you’re inexperienced, unsure, and fearful, you’ll need to do a lot more.

Do people expect too much too soon? Most certainly. And a lot of times the people who expect too much too soon are the ones who are afraid. They want the horse to come through, to get over all the things that he’s doing that frighten them without their putting in the time to help him. They want him to become advanced as soon as possible—if not sooner.

“Always go back to the basics” is something Buck stresses. As with playing scales on the piano, allow the horse to warm up with you. Here Buck does a little reminder groundwork with Bif.

On the other hand, people who have realistic expectations and enjoy working with a horse, allowing him to come along at his own pace, are the people who are confident. These are the people who don’t work with horses to stroke their own egos. They feel comfortable with the horse because they’re comfortable with where they are now. And that helps them be comfortable with where they’re headed.

People talk about horses that are lazy. That may be their opinion, but a lot of times I know it’s something else. Having been through hard times myself, I know what it’s like to be in a situation where you’re basically a captive. That’s where many of these so-called lazy horses are. They’re captives doing time. As a kid, I couldn’t go anywhere else physically, but mentally I didn’t have to stay. Often the only way I could survive a really stressful situation was to go somewhere else in my mind.

Many people survive just that way when they’re young, and I feel sure that horses do, too, a lot of the time. They can’t open a gate, hitch up the trailer, load themselves, start the truck, and drive off. Physically they’re captives, and they have no choice but to remain. Because of a stressful life, an unhappy life with a human, those horses have to go away somehow. They have to leave in order to survive.

When horses do go somewhere else, their response may be very aloof. Humans will think that they’re lazy or that they don’t care, that they lack desire. These horses do not lack desire. They have lots of desire, but their desires can’t be fulfilled because they’re living in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Therefore, I’ll tell people who ask me whether their horse is being dull or listless or lethargic that the horse may have had to go away mentally to preserve the one and only thing that means anything to him. That’s his state of mind, his well-being. It isn’t always the case, but I’ve seen it happen quite a bit.

I don’t know that there is such a thing as a bad horse, but some are certainly more difficult to work with than others. It isn’t always the fault of the owner. Sometimes, the owner has the best of intentions but lacks the knowledge, the ability, or the means to work with a horse that is in trouble. Horses just want to survive, and it can be hard for them to fit into the world we have created for them.

Some horses are so easy to work with that we refer to them as “born broke.” These horses are open to just about anything we want to do with them. However, others aren’t real inclined to get along with us. Some of them are so afraid of losing their lives that they are very difficult to work with. Either way, the responsibility lies with us. As horsemen, we have the ability to adjust to the needs of the horse as well as to his individual personality. We have what it takes to get along with him. Some people find a very troubled horse too much to deal with; selling him might be the best thing they could do.

Occasionally you will find a horse born with very limited possibilities. These are no different than children who are born retarded. Sometimes, a foal will get the placenta over his nose, become starved for oxygen, and then suffer brain damage before the mare can pull the placenta off. Or a horse is born with some sort of birth defect that makes it difficult or impossible to perform normally. With such horses, you try to do the best you can, and if they fall short of becoming great horses, you accept them for what they are and make the best of it. Horses can be only as good as they can be. The best thing you can do is wait until you know any horse before you begin to have expectations. Before that, you need a general knowledge of horses. And then you do the best you can with what you have to work with.

Some horses progress faster than others. Buck is able to lope this horse in the round pen on a loose rein.

Punishing a troubled horse for what you determine to be bad behavior is punishing him for something that in your mind is wrong. But it isn’t wrong in his mind. He’s only trying to do what he believes he needs to do at the time. As a horseman, you should have the wisdom to see how the horse prepares himself and to understand what he has in mind.

Then, if what he has in mind isn’t what you’re looking for, you head him off. You redirect him. You change his mind. You change the subject, and you keep on changing it until after a while the negative behavior disappears.

I don’t believe in waiting for a horse to do the wrong thing and then punishing him after the fact. You can’t just say no to a horse. You have to redirect a negative behavior with a positive one, something that works for both of you. It’s as though you’re saying, “Instead of doing that, we can do this together.”

When things start to go wrong with a child, there is nothing wrong with laying down some rules, with being strict and saying no. You can talk to a child, reason with him, but you still need to give him a choice. You need to give him someplace else to go in his mind, and something else to do so that he can succeed.

If you don’t, if you wait for him to do the wrong thing because you weren’t paying attention to your responsibilities and then you become angry and beat on him, he won’t learn anything from what he did. He’ll learn to fear you. He’ll learn to be sneaky and covert about what he does. He may never learn to do the right thing. Instead, he is likely to learn nothing but how to fail.

Now, I’m not saying that everything is milk toast, fuzzy, and warm when you are working with a child or working with a horse. But at the point you become angry or you abandon your sense of reason and logic and become ruled by resentment and anger, by spite and greed and hate and all the other negative feelings that seem to run the world these days, you aren’t going to be any more successful with your horse than you would be with your child.

Unlike a child, a horse makes it pretty convenient for you to live your life this way. You can say all kinds of things about him, and he is never going to step up to the microphone and say, “Hey, world, let me tell you about this human. Let me tell you what he’s made of.” But a horse will still make his feelings known, and if you have mistreated him because of your inadequacies, his behavior will tell on you. You may meet someone like me who will tell you what the truth of his behavior means. You may not enjoy hearing it, but the truth doesn’t go away.

You can tell a lot about an owner’s character by observing the behavior of the horse. Some people come to a clinic to become a little safer on their horses because they’re scared or worried. Maybe their horses are scared and worried, too. Overcoming such problems is easy to accomplish over a period of days. I can help people become more confident and understand their horses a little better.

Quite often I’ve had people come to my clinics who are too passive. They don’t assert themselves in ways that evoke respect from other people or from their horses. Because these owners behave like victims, their horses may have bitten them or responded in other disrespectful ways that reflect an owner’s overly passive nature.

Many such people come to my clinics because, consciously or not, they’re searching for a sense of strength that they haven’t found elsewhere. A woman may have been pushed around or bullied by her husband or her kids as well as by her horse. Learning a little bit of horsemanship—learning how to take charge, set a goal with the horse, and then achieve it—can be a very liberating experience. It can have a positive influence and permeate the rest of her life.

Women often acquire a new perspective toward their lives and a new self-confidence during my clinics. They reassess their lives and relationships, and they often “clean house” when their husbands or boyfriends don’t measure up or adapt to their new approach to life.

Other people are overly aggressive. I’ve had men who are too embarrassed to treat their horses in public the way they treat them at home. But their horses won’t cover for them. Whatever the owner is like with the horse at home becomes apparent at the clinic, because the horse will behave in a way that reflects the treatment he’s used to receiving. That’s what I mean when I talk about a horse’s honesty. And thank goodness they are that way—they would be difficult animals to work with if they were liars on top of being so athletic.

Many times people have told me that what they’ve learned from me about understanding their horses has helped them begin to understand themselves a little bit better and then allowed them to make changes that improved their lives far better than they could have ever imagined.

One such person was a chariot racer who lived near Big Horn, Wyoming. Chariot racing is a winter sport, and it has a following in some parts of the West. It’s a lot like what Charlton Heston did in the movie Ben Hur, except the chariots aren’t usually quite as fancy and the horses that pull them tend to be about half broke. Some of the horses have never even been taught to drive. The racers harness them up, beat them over the rump, and away they go over frozen ground or through snowfields.

When the man from near Big Horn tried to harness a horse and teach it to drive, they got into a fight. The man lost his temper and beat the horse with a two-by-four until the horse was unconscious. Somebody called a veterinarian, but it was too late. The horse was still unconscious. He wasn’t dead, but there wasn’t anything the vet could do, so he had to put the horse to sleep.

Someone called the sheriff, and the man ended up in front of a Sheridan County judge. The charge was animal abuse, and the vet, a Dr. Wilson, was one of the witnesses against him. After the judge heard the case, he asked the vet what he thought an appropriate punishment might be. The vet suggested ordering the man to pay to take one of his other young horses to one of my clinics. He t--hought that teaching the man how to properly start a colt might help him learn something about understanding horses, an education that would be more effective than simply hitting him with a big fine. The judge agreed.

I hadn’t yet moved to Wyoming from Montana, but I’d been giving clinics in the Sheridan area for a while, and the person who organized my clinic there told me about the chariot racer’s offense and the judge’s sentence.

On the one hand, I wanted to hate the man for what he had done to my friend, the horse. But after considering the situation, I realized that the man most likely expected me to hate him. He had probably hardened himself to what was coming, and he was mentally prepared to get through whatever hostility he might experience.

When the man showed up at the clinic, I treated him no different than any other student. Giving him the benefit of the doubt, I acted as though he’d done nothing wrong. The locals knew, of course. There was a lot of whispering about who he was and the horrible thing that he had done, so you can imagine the shame and regret the man must have felt.

I was the only person there who treated him well, and after a day or two he started to make progress. He started asking questions, and by the time the clinic was over, he and his colt were doing pretty well.

After everybody else had said their good-byes, the man stood off by himself near the corrals. I was loading my trailer when he came over. He was a big man, over six feet tall, and weighing about 225 pounds. He just stood there for a while.

I waited until he spoke. “I don’t know what to say,” he began. “This weekend has changed my life, and in more ways than you will ever know.” With that he started to cry.

I gave him a hug. “I may never see you again,” I told him, “but I hope what you’ve learned helps carry you through times when it’s hard to control your emotions. I hope you find the wisdom you need to fix some of the things that aren’t okay in your life.”

He nodded, then shook my hand. “Well, thanks for giving me a start.”

Dr. Wilson was a wise man. So was the judge. Making that defendant attend one of my clinics turned out to be as good a punishment as could have been dished out. He went through a few life-altering days, which also validated something for me, too. My initial inclination had been to be mean and vengeful because of what the man had done to the horse. Yet if I had, if I had approached him as an enemy, I wouldn’t have accomplished anything. There would have been no chance for him to learn a better way.

To have been able to play even a small part in helping someone change his life simply because he’s been to a Buck Brannaman clinic is a very humbling experience. I’m grateful for the opportunity. It is a real blessing, and when people lean on me for emotional and psychological support, I take the responsibility seriously. I do the best I can to help them along because we’re all trying to figure out how to live our lives, how to get by, and how to answer a few simple questions. We’re all involved in the same search. Horses, like people, should be treated how you want them to be, not how they are.

There are so many variables in a clinic that I can’t control: where the horses are coming from; whether they’re scared, upset, or otherwise bothered. Nor do I have control over where the students are coming from or whether or not they’re going to be able to help the horses when they need help. I can tell students what they need to do, but I can’t do it for them, and there’s always an underlying worry that someone will get hurt or even killed (I can laugh now about Polack and the water jug, but it wasn’t very funny at the time). A person can fall off a horse as easily as he can fall out of the back of a pickup truck or even stumble on the way to the bathroom and bump his head on the sink.

We all know that there’s a chance you can lose your life doing some of these things. But a person’s dying at one of my clinics, even if only due to sheer accident—the sort of thing that can happen to anybody, anywhere, anytime—could negate every bit of good I’ve ever done, no matter how many people I’ve helped or how many horses I’ve saved from the slaughterhouse. It doesn’t seem fair, but it could happen. I always live in fear of something like that, and I just have to leave it up to the good Lord to help my students and me through.

In a clinic in Boulder, Colorado, I had about twenty people in the colt class. All but one of them were doing their groundwork, helping their horses get comfortable and readying them to be approached and handled. The man who wasn’t doing the work owned a little paint colt that he’d tried to have started before. He had hired a local horse trainer who had failed. The colt was afraid of the trainer, and she was afraid of him.

Once Buck gets a saddle on a young clinic horse he goes through all the same actions he had previously done with the horse unsaddled. This is to reinforce that the horse has nothing to fear after the saddle is cinched up.

The clinic began with groundwork to establish the essential connections between horses and their owners. This owner, however, didn’t participate in this phase. When I asked him why he wasn’t working with his horse, he replied, “I’ve had enough of this bullshit. I’m ready to get on this colt and ride.”

I was more than a little shocked at the answer. “Well, sir,” I said, “these other people are trying to get their horses comfortable enough to where they can get on them. I can’t make you do this groundwork, but your horse is a little bothered. I’d think you’d want to be working at having a little better relationship with him than you do. But even if you don’t, you’ll have to be patient because we aren’t ready to get on the colts yet.”

People who overheard the man couldn’t believe that he wasn’t more interested in working with his colt, since he had paid good money to do just that.

An hour and a half later, students were getting on their horses for the first time in the round pen and getting along fine. The man in question was one of the last ones to get on. I held on to his lead rope from the back of my saddle horse, and I asked him to make sure his cinch was tight. He said it was. Because he was a big man, I then asked him to get on about halfway, nice and smooth, but he still wasn’t following my directions. He stepped up and got on almost halfway when the saddle slipped. It turned under the horse’s belly, and he had to step off.

The turning saddle had pinched the little paint’s withers. It scared him a little, but the horse recovered and still tried his best.

The man tightened his cinch, got his horse reorganized, and made another attempt to get on. He put his left foot in the stirrup, leaned over the back of his horse, grabbed him by the mane as I’d told him to do, and swung up. He had some trouble fishing around for his right stirrup, but he finally got his foot in.

Now he was sitting on his horse. At this point I asked him to do what I had asked the others to do: reach forward and rub his horse’s neck, the same way its mother had nuzzled or licked him when the little paint was a foal.

Once again the man didn’t follow directions. Instead of trying to soothe the horse, he reached up and slapped him on the neck in a very macho way. The sudden impact startled the horse, who moved his hindquarters six or eight feet to the left. The man’s balance was so poor, he fell off. There was a snapping sound, and the man grabbed his leg up high by the hip.

Everybody got off their horses and led them out of the corral. While we were waiting for the ambulance, the man kept saying, “I’m sure sorry. I messed up the clinic for everybody, and it’s not anybody’s fault. It’s my own fault. And I’m sorry. I’m sorry.”

“It’s all right,” I told him. “Don’t worry about it. We’ll get you off to the hospital and get you fixed up.”

The ambulance came and took the man off to the hospital. I asked someone else to ride his horse, and before the clinic was over, the little paint was taking part in my advanced horsemanship class, loping around out in the pasture and getting along just fine.

I was really proud of the horse, and I thought his owner would be happy that he had continued. The man had broken his leg, and when I checked on him a few times in the hospital, I reported on his horse’s progress, wished him well, and told him I was sorry he’d had bad luck. And that, I thought, was the end of the story. I left town and went on to the next clinic.

About a year later, I was doing another clinic in the same arena when a kid in a T-shirt walked in. He didn’t look as if he fit in at a horsemanship clinic, and he didn’t. He was a process server. Right there in the middle of my clinic he served me with papers saying that my clinic’s sponsor and I were being sued for wanton and willful negligence. The little paint’s owner had accused us of having tried to get him hurt or killed, and that our intentions had been premeditated. He wanted a million dollars.

Nothing like that had ever happened to me. How could the man sue me for something I tried so hard to prevent? I was so upset that I just wanted to cry right then and there in front of everyone.

I had no insurance to cover such a matter, and I ended up spending thousands of dollars—that I didn’t have—for an attorney I shouldn’t have needed to defend myself from something over which I had no control.

The legal wrangling went on for the next couple of years. Over the course of the lawsuit, the million-dollar claim that the man had been after was reduced to ten thousand; his lawyer was looking for an out-of-court settlement to get his client something so the lawyer could make something for himself.

The night before we were to go to trial, my lawyer called. “If you give this man one of your custom-made saddles, he’ll drop the case.”

I was outraged. “You tell him that if he wants one dollar to settle out of court, he can go to hell.” I had my principles, even if I was going to spend the rest of my life paying for them. I knew that the horse hadn’t done anything wrong, and I hadn’t done anything wrong. The only thing that got that man was gravity.

I was staying with friends in Boulder during the lawsuit. As I was about to leave for court the next morning, I received a call from a funeral home in Arizona. My father had died. The funeral director had been trying to get ahold of me for several days. He wanted me to sign a release allowing my dad to be cremated. He also said that the memorial service was to be held that day.

I called Smokie with the news. He was living on Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, and even if he had wanted to attend the service, he couldn’t have gotten there in time.

That day marked the end of all my hard feelings and memories of torment. I would very much have liked to have been at his service to say good-bye, but I couldn’t go. I had to be in court.

While I was on the witness stand and the opposing lawyer was asking me questions, I broke down and began to cry. “What’s wrong?” the lawyer wanted to know. He couldn’t understand why his questions had provoked so much emotion.

“What’s wrong is that I’m sitting here in court defending myself from something that even you know that I had no control over. I’m sitting in this court, wasting my time, when I could be at my own father’s funeral.” I looked at the judge and then the jury. “Instead, all of you are getting my time today because if I didn’t show up for something like this, by default you’d give this sue-happy man and his lawyer everything I have ever worked for and everything I will ever work for. This is a choice I had to make today. It’s a hard day for me.”

The jury found on my behalf and awarded the man nothing. They agreed there was no fault on my part. The man had simply lost his balance and fallen off his horse.

Dad owned a little piece of property in Chino Valley, Arizona. He had some furniture that he’d made as a young man, as well as family pictures and a few of his great-grandfather’s guns that had been passed down through his family. None of it was worth a lot of money, but he’d intended to leave them to me. A few days before he died, Lillian, the woman he had been living with, got him to change his will. I don’t know if they were married or not, but she was his companion and had been looking after him. As a result of Dad’s changing his will, all I inherited was a handful of pictures of my mother. Everything else was gone. Smokie and I never got any of it.

I didn’t hate my dad when he died. At some level, I loved him. I didn’t love him as I loved Forrest. Forrest was my teacher; he was the man who raised me and prepared me for life. My dad was the one who showed me the kind of man I have worked hard not to become. In that sense, you could say I learned a lot from him as well.