Suffrage and Antisuffrage

Prior to the Civil War the South showed little interest in woman’s enfranchisement. During Reconstruction the issue was raised in several constitutional conventions, but in no state were women granted the right to vote. After Reconstruction woman suffrage became associated with the South’s desire to reduce the importance of the black male vote. A widely discussed proposal was the enfranchisement of women with educational and/or property qualifications. This extension of the franchise would include black as well as white women. Fewer black women would be able to meet these requirements, so the proportion of white voters would be increased. The strength of the black vote would be diluted, and white control of southern politics would be assured.

Proposals to enfranchise women meeting certain qualifications were introduced in constitutional conventions in Mississippi (1890), South Carolina (1895), and Alabama (1901). None of these proposals was adopted, however. Involving women in politics was contrary to southern cultural traditions, and southern men were unwilling to use this stratagem even for the purpose of coping with the vexing race issue.

In 1892 the National American Woman Suffrage Association established a special committee on southern work. Laura Clay of Kentucky chaired the committee, composed of southern women. The committee endeavored to influence public opinion through the distribution of literature and sponsoring lectures. Due largely to its efforts, suffrage organizations formed in all the southern states before the end of the decade.

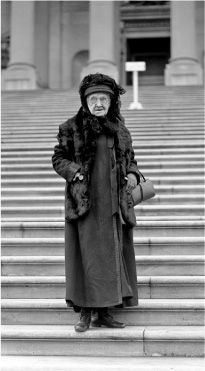

When crusading for the ballot, southern women followed the guidelines of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. They conducted their agitation with dignity and restraint, avoiding the militant tactics advocated by Alice Paul’s National Woman’s Party. This party organized branches in the southern states, but its following there was small. It conducted no militant agitation in the area, but some southern women participated in such activities in the nation’s capital. The oldest of the White House pickets and suffrage prisoners, for example, was a southern woman, 73-year-old Mary C. Nolan of Jacksonville, Fla.

The suffragists assured the public that enfranchisement would enable women to be better wives, mothers, citizens, and taxpayers. They would use their votes for the general betterment of society. The antisuffragists countered by arguing that enfranchisement would constitute a threat to the home and the family. Participation in politics would coarsen women and cause them to lose their femininity. It would also cause them to neglect their household duties and would lead to quarrels between husbands and wives.

The “antis” did little organizing in the South and can hardly be considered to have had a movement there. Their strength lay in their appeal to traditional prejudices and to generally established values. They were endeavoring to maintain the status quo while the suffragists were working for change.

The suffragists established lobbies in state capitals. Bills to enfranchise women were introduced in state legislatures, but they were seldom passed. In only three states were significant gains made. In Arkansas in 1917 the legislature passed a law permitting women to vote in primary elections. The following year Texas passed a similar law. In 1919 Tennessee granted women the right to vote for presidential electors and also the right to vote in municipal elections. No southern state, however, allowed full enfranchisement.

When the federal woman suffrage amendment was submitted to the states for ratification, it encountered its strongest opposition in the South. Many southerners considered suffrage a state, not a federal, matter and feared that ratification would mean federal control of elections. Others held that the enfranchisement of black women would reopen the entire issue of the African American’s role in politics. Some predicted that it would usher in another era of Reconstruction.

Suffragists in early 20th-century Kentucky (Photographic Archives, University of Louisville, Louisville, Ky.)

In June 1919 Texas became the first state in the South to ratify the Susan B. Anthony Amendment. A few weeks later, Arkansas followed. Kentucky ratified in January 1920. In July 1919 Georgia became the first state in the Union to reject the proposed amendment. Georgia’s example was soon followed by Alabama, South Carolina, Virginia, Mississippi, and Louisiana.

By August 1920, 35 states had ratified. The approval of only one more was needed. The governor of Tennessee submitted the question to a special session of the legislature. A bitter controversy ensued. Those opposing ratification called the proposed amendment a peril to the South and urged its rejection. Those in favor maintained that eventual ratification was a certainty and that Tennessee’s refusal could only delay it. After much emotional debate and political maneuvering, both houses of the legislature approved, and on 26 August 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment became part of the U.S. Constitution.

Two southern states refused to accept woman suffrage as the supreme law of the land. Mississippi and Georgia did not allow women to vote in the general election of 1920, claiming that the Nineteenth Amendment had been ratified too late to permit women to comply with state election laws. Georgia’s leading suffragist, Mary Latimer McLendon of Atlanta, telegraphed the secretary of state in Washington, seeking his opinion in regard to her eligibility to vote. Her effort was in vain, however, because he refused to become involved.

During the months that followed, Mississippi and Georgia yielded, and woman suffrage prevailed throughout the South. Women voted and held office. And the fears of the “antis” were not realized. Women did not lose their femininity, nor did they neglect their homes for politics. Only a few aspired to political careers.

The South’s strong opposition to woman suffrage was a result of the South’s basic conservatism, its devotion to the ideal of the patriarchal family, and its fear of federal interference in elections. Having no alternative, the South accepted enfranchisement but remained conservative in its attitude toward women and the family. The advent of woman suffrage apparently resulted in no appreciable change in the fundamental nature of southern culture.

A. ELIZABETH TAYLOR

Texas Woman’s University

Clement Eaton, Georgia Review (Summer 1974); Paul E. Fuller, Laura Clay and the Woman’s Rights Movement (1975); Elna C. Green, Southern Strategies: Southern Women and the Woman Suffrage Question (1997); Kenneth R. Johnson, Journal of Southern History (August 1972); Suzanne Lebsock, in Visible Women: New Essays on American Activism, ed. Nancy Hewitt and Suzanne Lebsock (1993); Anne Firor Scott, The Southern Lady: From Pedestal to Politics, 1830–1930 (1970); A. Elizabeth Taylor, Journal of Mississippi History (February 1968), South Carolina Historical Magazine (April 1976, October 1979), The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee (1957); Rosalyn Terborg-Penn, African American Women in the Struggle for the Vote, 1850–1920 (1998); Mary Martha Thomas, The New Woman in Alabama: Social Reforms and Suffrage, 1890–1920 (1992); Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, New Women of the New South: The Leaders of the Woman Suffrage Movement in the Southern States (1993); Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, ed., Votes for Women! The Woman Suffrage Movement in Tennessee, the South, and the Nation (1995).

Visiting

Human beings have probably “visited” ever since they developed enough language and leisure to communicate about something other than access to food, safety, and a mate, but southern Americans have tended to make visiting especially central to their lives. Joe Gray Taylor quotes an Alabaman who, in the 1920s, described visiting as a “happy recreation,” which was, nevertheless, taken “very seriously.” Southern newspapers still include reports about people visiting from out of town, whether in a society column focused on the local elite or in reports from small-town church congregations. Certain common expressions of hospitality have long reflected the belief that southerners should always give the appearance of being willing to set aside whatever they are doing to visit with someone: “Y’all come to see us sometime”; “Come again real soon”; and “Come set a spell.” Southerners announce that they have “had a good visit” with someone and usually mean that their conversation made them feel closer and that they are looking forward to seeing each other again.

The primary purposes of any visit have usually been to have fun and escape daily worries, to help each other solve problems, and/or to establish and reinforce personal ties. There has not been enough research to determine what visiting traditions, if any, have been exclusively southern, but many practices have been affected by their cultural and historical contexts. Until the 20th century, most southerners lived in relatively isolated rural settings, making them especially appreciative of any opportunity to talk with anyone, whether neighbors or strangers. Until the spread of air-conditioning, people wishing to escape both the summer heat and the isolation of their houses would sit on front porches where they could invite passersby to join them for a chat. The Sunday highlight for many churchgoers has been the chance to visit after the service either outside or in a “fellowship hall.” At weddings, funerals, revivals, and other special gatherings, southerners have talked around tables “groaning” with massive platters of food (or, before football games, by the “tailgates” of each other’s cars and trucks). Small sets of people wishing to be alone, particularly courting couples, have, throughout southern history, “gone for a ride,” whether on horseback, in a carriage, or in an automobile.

The enduring social hierarchies in the South inspired complex regulations about who can see whom under what circumstances and how each individual should behave. Men have staked out special contexts for stag visits, including fishing, hunting, militia musters, political meetings, business luncheons, private clubs, locker rooms, bars, brothels, gambling, and various sports venues. Small-town men have gathered to chat and play cards or checkers in front of courthouses, in barbershops and country stores (sometimes open late to serve as a male community center), and, in recent decades, at a common table in “meat and three” restaurants. Melton McLaurin noticed that men in his grandfather’s store kept rehashing the same subjects rather than approaching topics that might stimulate tensions, but many male conversations have ended in fights, especially when they were fueled by alcohol.

Women have been most apt to visit in each other’s kitchens or parlors, in beauty shops (significantly called “beauty parlors” by many southern women), or while shopping together. Urban ladies of the 18th century followed the English pattern of holding “tea-tables,” at which they discussed fashions and people who were not present. Gossip has often been the special purview of females, allowing them to share opinions on who needed to be helped, reined in, or shunned. The primary “work” for the wives and daughters of wealthy planters, besides making sure that their servants did as bid, was to nurture relationships with other elites through frequent visits. One young antebellum wife complained about having to give up her quiet days at home “to pay morning calls” but acknowledged that it was “a duty we all owe society, and the sacrifice must be made occasionally.”

Heterosexual visits have occurred most often at parties, whether casual and spur of the moment or formal and planned. Each generation of southerners in each class has set standards for what kind of visiting was suitable for young men and women with romance on their minds. Until they were ready to court seriously one special female, 19th-century young males tended to gather in small groups and then visit a series of young women. Young people of the New South spent entire evenings riding a streetcar, much as their great grandchildren would “hang out” at a mall. For most of the 20th century, however, couples went on formal “dates,” during which the young women were expected to feign interest in whatever fascinated their male companions.

Although visiting has never been an exclusive class privilege, access to particular gatherings has often been restricted. The wealthy have always had more leisure time, as well as more money to spend on food, drink, servants, and congenial private and public spaces in which to entertain, but this may have made opportunities to visit more precious to people who had to spend most of the day working. Zora Neale Hurston, in Their Eyes Were Watching God (1937), describes members of an all-black community who “had been tongueless, earless, eyeless conveniences all day long” enjoying “the time for sitting on porches” when they might “hear things and talk.” Members of the lower classes have faced restrictions on their ability to unify through visiting since the earliest slave traders prevented Africans with the same language from being chained next to each other. Mills and other workplaces have been decorated with “no talking” signs. In spite of this, workers have met clandestinely in the woods and swamps of plantations, at times when overseers were out of sight, in workplace and school bathrooms, and during coffee and smoking breaks. Such visits have often included making jokes about the authorities.

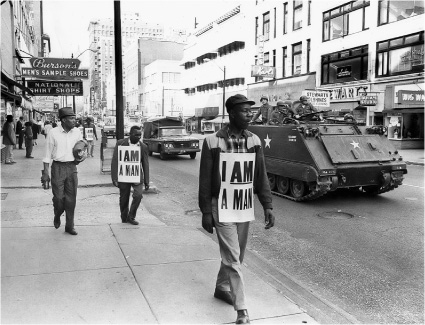

The most significant visiting taboo in southern history has been against people of different “races” interacting as if they were peers. White men could have sex with both willing and unwilling black women, but they were never to be caught eating at the same table with African Americans. White women and their enslaved or free black servants might gossip together and help each other in childbirth, but they were never to let their “friendships” develop to a point that might challenge their social differences. Byron Bunch, in Faulkner’s Light in August (1932), criticized Lena Grove, the daughter of humanitarian carpetbaggers, for visiting sick black people “like they was white.”

In the 20th century, historical developments such as the civil rights movement and the migration of northerners to the South eroded some of the restrictions concerning who can interact with whom. Visiting practices among 21st-century southerners are probably less distinctive than in earlier times, but visiting, for whatever reasons and in whatever form, remains a favorite pastime across the South.

CITA COOK

State University of West Georgia

John W. Blassingame, The Slave Community (1979); Joyce Donlon, Swinging in Place: Porch Life in Southern Culture (2001); Elizabeth Fox-Genovese, Within the Plantation Household: Black and White Women of the Old South (1988); Jacquelyn Dowd Hall et al., Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World (1987); Crandall A. Shifflett, Coal Towns: Life, Work, and Culture in Company Towns of Southern Appalachia (1991); Joe Gray Taylor, Eating, Drinking, and Visiting in the South (1982).

Womanism

The majority of African Americans live in the South, and African American communities throughout the United States are influenced substantially by southern culture and its racialized history. Movements for social change and organizations advancing African American interests often survive and succeed because of the presence of black southerners, usually women. African American women are recognized as consummate organizers in their churches and communities, and it is said that one civil rights leader commented, “If the women ever leave the Movement, I’m going with the women because nothing is going to happen without the women.”

The civil rights movement brought a variety of activists to the South, including large numbers of white women. In its aftermath, white women, including some civil rights activists, sparked a feminist movement that challenged patriarchy and generated new modes of thinking about gender and women’s experience. Although white feminists claimed black southern women like Fannie Lou Hamer, Gloria Richardson, Rosa Parks, and Daisy Bates as their role models, feminism emerged as a primarily white movement. In the words of some black feminist critics, “All the women are white.” Consistent with American racial hierarchies, white women’s experiences provided the foundation for feminist thought; the problem of racism was presumed to be subsumed within the problem of patriarchy.

Alice Walker (b. 1944), black woman and southern writer, created the term “womanist” in 1981. Novelist, poet, essayist, literary critic, and feminist, Walker discovered the limits of feminism as she sought to relate the issues and ideas identified by white women to the lived experience of black women. Seeking to integrate human liberation and self-definition, Walker eventually fashioned a succinct but very rich dictionary-style definition of her new term as a preface to In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose, her 1983 book of essays. With that definition, she provided the foundations for a theory of black women’s history and experience that highlighted their significant roles in community and society. Heavily and enthusiastically appropriated by black women scholars in religious studies, ethics, and theology, womanist ideas became important tools for understanding black women’s perspectives and experiences from a standpoint that was self-defined and that resisted the cultural erasure that not only was a destructive component of American racism but was also rapidly being replicated in American feminism.

In all of her writings—fiction, poetry, and prose—Walker struggled against the invisibility of black women. She brought ordinary southern black women into the foreground in her novels and recovered the writings about black southern women by black writers like Zora Neale Hurston, a southerner, and Jean Toomer, a traveler in the South. Inspired by Hurston, who was not only a novelist but also an anthropologist, Walker’s novels and poems offered close and thick descriptions of southern black culture and connected that culture to national and global issues. In her short stories, especially in the volume You Can’t Keep a Good Woman Down, Walker used issues raised by white feminists to raise questions about the contradictions surrounding gender in African American life and culture. At the same time, Walker also examined the intricate contradictions of white and black women’s behavior in a system of white privilege, most dramatically in a short story titled “The Welcome Table” in In Love and in Trouble.

Walker used black women’s history, black women’s various forms of solidarity, and African American spirituality to construct her very complicated novel The Color Purple. That novel contains a tremendous amount of detail about black southerners and the complicated world they faced as they sought to survive with a degree of economic self-sufficiency, autonomy, and self-respect in the face of the violent opposition of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Walker was critical of the ways in which white feminists used their own experiences to interpret black women’s experiences, thus ignoring or misinterpreting black women’s history.

Walker first used the term “womanist” in a 1981 review of Jean Humez’s book, Gifts of Power: The Writings of Rebecca Jackson, Black Visionary, Shaker Eldress. The review was reprinted in In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens. Shakers built a religious movement that required its members to be celibate. On becoming a Shaker, Rebecca Cox Jackson left her husband and assumed a life of celibacy. Because, like most black women missionaries, evangelists, and club women of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Jackson traveled with a woman partner, Humez chose to call Jackson’s lifestyle “lesbian.” Walker objected to Humez’s use of a term that was not grounded in Rebecca Cox Jackson’s definition of the situation. Walker questioned “a non-black scholar’s attempt to label something lesbian that the black woman in question has not.”

Within the review, Walker laid the foundations of her definition. She rejected a term for women’s culture based on an island (Lesbos) and insisted that black women, regardless of how they were “erotically bound,” would choose a term “consistent with black cultural values”—values that emphasized communality—“regardless of who worked and slept with whom.” “Womanist,” as defined by Alice Walker, clearly “affirmed connectedness to the entire community and the world, rather than separation.” Humez’s choice of labels was an example of the ways white feminists perpetuated an intellectual colonialism. This intellectual colonialism reflected the differences in power and privilege that characterized the relationships between black and white women.

With the term “womanist,” Walker provided a word, a concept, and a way of thinking that allowed black women to name and label their own experiences. The invention of the term was an act of empowerment and resistance, which addressed and challenged the dehumanizing erasure of black women’s experience. Walker’s more elaborate definition provided a more extensive view of Walker’s understandings of the experiences and history of black women as a distinctive dimension of human experience and a powerful cultural force.

First of all, Walker defined a “womanist” as a “black feminist or feminist of color,” thus including the liberationist project of feminism in her definition. However, Walker gave the term an etymology rooted in the African American folk term “womanish,” a term African American mothers often used to criticize their daughters’ behavior. Traditionally “womanish” meant that girls were acting too old and engaging in behavior that could be sexually risky and invite attention that was harmful. Walker, however, co-opted “womanish” and used it to highlight the adult responsibilities that black girls often assumed in order to help their families and liberate their communities. Rebecca Cox Jackson lost her mother at age 13 and helped raise her brothers and sisters along with one of her brother’s children. As a civil rights worker in Mississippi Freedom Schools, Walker taught women whose childhoods ended early, limiting their educations. Walker also observed the participation of young people in civil rights demonstrations and was aware of the massive resistance of children in places like Birmingham and Selma, Ala. Walker described the term “womanish” as being opposite of “girlish,” subtly hinting that the pressures of accelerated development were the facts of black female life, which were not understood by white women’s experiences or their meaning of “feminist.” Walker’s term “womanist” implied a desire to be “responsible. In charge. Serious.”

A womanist, according to Walker, loves other women and prefers women’s culture, a very antipatriarchal orientation. However, womanists also evince a commitment “to survival and wholeness of entire people, male and female.” A womanist is “not a separatist, except periodically, for health,” and, as a “universalist,” a womanist transcends sources of division, especially those dictated by color and class. Walker offered a new approach to the antagonisms of class and color among African Americans, problems often overemphasized by black nationalists. For a womanist, these issues were differences among family members. A womanist also has a determination to act authoritatively on behalf of her community. Walker evoked very specific black women role models, like Mary Church Terrell, a club woman whose politics transcended color and class, and Harriet Tubman, famous for her exploits on the underground railroad and the Civil War battlefield.

Finally, Walker offered a description of black women’s culture that was at odds with some major emphases in white culture. Walker’s key word was “love,” and she linked it to spirituality, creative expression, and political activism. Her definition included a love of “food and roundness,” which stood in stark contrast to the body images and gender norms of the dominant culture, a culture that celebrated pathologically thin white women and socially produced eating disorders. Finally, Walker emphasized self-love, a woman “loves herself, regardless,” a direct challenge to the self-hatred that was a consequence of racism.

Although “womanist” has not displaced the terms “feminist” and “feminism,” the womanist idea resonated with many black women as a grounded and culturally specific tool to analyze black women’s experiences in community and society. Walker’s idea was particularly useful for black women in religious studies and theology, where the confrontation between black and white theologies, in the context of debates over liberation theologies, was particularly vibrant and direct. In normative disciplines such as ethics, theology, and biblical studies, the idealism and values in Walker’s idea were especially helpful. Ironically, all of the pioneering black women scholars who first used the term “womanist” in their work were southerners: Katie Geneva Cannon, author of Black Womanist Ethics; Jacqueline Grant, author of White Women’s Christ and Black Women’s Jesus: Feminist Christology and Womanist Response; Renita Weems, author of Just a Sister Away: A Womanist Vision of Women’s Relationships in the Bible; and Delores S. Williams, author of “Womanist Theology: Black Women’s Voices” and Sisters in the Wilderness: The Challenge of Womanist God-Talk. These scholars used Walker’s perspective to explore the relationship of African American women’s experiences to the construction of ethics, to theological and Christological ideas, and to the meaning and importance of biblical stories about women.

Although bell hooks (also a southerner), in her book Talking Back: Thinking Feminist, Thinking Black, suggested that some women used the term “womanist” to avoid asserting they are “feminist,” the issue is more complex. Many black women who were self-identified as feminists found that the emphases of late 20th-century white feminists did not match their own concerns and experiences.

Although Walker did not indicate a desire to create a womanist movement, the term “womanism” was a natural corollary and extension of “womanist.” Walker’s writings and ideas, however, emphasized black women’s creativity, enterprise, and community commitment, and “womanist” linked these specifically to feminism. Womanism was used to identify both the activism consistent with the ideals embedded in Walker’s definition, as well as the womanist scholarly traditions that have grown up in various disciplines, especially religious studies. “Womanism is,” as Stacey Floyd-Thomas points out, “revolutionary. Womanism is a paradigm shift wherein Black women no longer look to others for their liberation.”

CHERYL TOWNSEND GILKES

Colby College

Stacey Floyd-Thomas, ed., Deeper Shades of Purple: Womanism in Religion and Society (2006); Alice Walker, In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens: Womanist Prose (1983).

Workers’ Wives

Although attention has been given to upper-class southern women (for example, the “southern belle”) and slave women (for example, the “black mammy”), the wife of the southern worker has often been neglected. Not bound by the restrictions of racism or social demands to appear “ladylike,” the worker’s wife has been a significant contributor to southern history and society.

On the southern colonial farm, work was divided along gender lines. In addition to cooking, cleaning, and rearing children, women had responsibility for small animals, the dairy, gardening, and the orchard. Men cared for large animals, planted and harvested crops, and did general field work. But, in times of need, for example, during harvest season, sex roles on the colonial farm merged, as children and wife helped the husband bring in the crops.

The preindustrial work patterns continued into the antebellum South. As Frank L. Owsley noted in Plain Folk of the Old South, the wife of the yeoman farmer “hoed the corn, cooked the dinner or plied the loom, or even came out and took up the ax and cut the wood with which to cook the dinner.” The Civil War revealed both her productivity and her endurance; after her husband went off to fight, often with her encouragement, she took over the farms and shops, and women provided the bulk of the urban labor force.

As scholars have discovered, southern women have had a more active and important role in southern politics than has been traditionally assumed. The Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), antilynching crusades, and the progressive reform movements of the 19th and 20th centuries involved wives of southern workers, as well as middle- and upper-class women. But their role as political activists dates back even further. Workers’ wives, for example, were politically active in the 1600s in Bacon’s Rebellion in Virginia, and women such as Harriett Tubman were later involved in resistance to the slave system.

The industrialization of the South transformed to some extent the economic and social functions of women as well as men. In order to support their families, both husband and wife left the farm and took factory jobs. In Alabama, the number of men drawn into industry between 1885 and 1895 increased 31 percent, but the number of women increased 75 percent. In 1890 women constituted 40 percent of the workforce in the four largest southern textile plants. But their level of political activity did not change. Women, particularly wives of workers, were active in protesting child labor, and, like Ella May Wiggins of the Gastonia strike, they were heavily involved in southern industrial struggles.

Rural married couple, Bateville, Miss., 1968 (William R. Ferris Collection, Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

Nowhere was the importance and influence of workers’ wives more vividly revealed than in the southern coalfields. By law and superstition (a mine would supposedly explode if a woman entered it), women were prohibited from industrial work, that is, working in the coal mines. And because southern coal towns were usually in isolated, rural areas, women were not able to find employment in other industries, as did miners’ wives in northern coalfields. They hardly submitted, however, to the life of Victorian domesticity.

In the era before unions (1880–1933) men worked in the mines 10–14 hours a day, 6 days a week. Hence, their wives essentially controlled the domestic economy and ran the family. To assist the husband in supporting the family, wives continued their preindustrial roles of caring for the family garden, taking in boarders, and doing the laundry of company officials and single miners. And it was the wife who dealt with the daily frustration of keeping the house clean and sanitary in a town filled with coal dust and grime because the company refused to install sanitary facilities such as running water and sewers.

In the company towns that predominated in the southern coalfields, the home was hardly a “separate sphere” sheltering women from the cruelties of the competitive, “public” world, as was said to have been the case in northern urban areas. With her husband down in the coal mines, a wife dealt with the company store and had direct, day-to-day contact with company officials. Consequently, she most keenly and intensely felt the coal company’s abuse of power, especially its exploitation in the form of low wages, monopolistic prices, and the lack of sanitary facilities.

Women expressed their anger toward the coal operators in a number of ways, including song. Florence Reece, who wrote the classic labor song “Which Side Are You On?” after company police had driven her husband out of their company town, was but one of many female coalfield troubadours, a list that includes Aunt Molly Jackson, Sarah Gunning, and, more recently, Hazel Dickens.

Women expressed their desire for improved living and working conditions in the coalfields, as well as their anger, by becoming major advocates for unionization. The exploits of the legendary union organizer Mother Jones are well known. But Ralph Chaplin (author of “Solidarity Forever”) captured Jones’s appeal when he wrote, after hearing her speak: “She might have been any coal miner’s wife filled with righteous fury.” The miner’s wife helped ease the effects of labor strife by planting larger gardens and canning more food. Wages stopped, the usual source of food and clothing (the company store) was gone, and shelter was denied (miners were thrown out of company houses during strikes), and miners could not have succeeded in any coal strike without this extensive preparation.

Miners’ wives formed auxiliaries to the United Mine Workers of America to promote the union cause. These organizations, sometimes denigrated as separate, sexist, and unequal, nevertheless increased social awareness and camaraderie among coalfield women and provided needed moral and financial support for organizing the southern coalfields. And wives of miners fought, often violently, for the union. After witnessing a gun battle during a coal strike in West Virginia in 1912, a San Francisco journalist reported, “In West Virginia women fight side-by-side with the men.” Indeed, the wife’s hostility to the company and her role in strikes were so important that coal company officials often took elaborate measures to encourage women’s involvement in company-town life.

As the Academy Award–winning movie Harlan County, USA revealed, wives of miners still play a significant role in the unionization of the coalfields. The relative ease with which women have entered the coal mines as workers suggests that the coalfields may be a less “macho” culture than once assumed. Wives of workers in other southern industries and occupations have faced obstacles similar to those faced by miners’ wives and have made similar contributions.

DAVID A. CORBIN

Washington, D.C.

David A. Corbin, Life, Work, and Rebellion in the Coal Fields: Southern West Virginia Miners, 1880–1922 (1981); Margaret J. Hagood, Mothers of the South: Portraiture of the White Tenant Farm Woman (1939, reprint 1977); Lu Ann Jones, Mama Learned Us to Work: Farm Women in the New South (2001); Lorraine Gates Schuyler, The Weight of Their Votes: Southern Women and Political Leverage in the 1920s (2006); Anne Firor Scott, The Southern Lady: From Pedestal to Politics, 1830–1930 (1970); Julia Cherry Spruill, Women’s Life and Work in the Southern Colonies (1938); Melissa Walker, All We Knew Was to Farm: Rural Women in the Upcountry South, 1919–1941 (2000).

Ali, Muhammad

(b. 1942) BOXER.

“Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee” are the words most often attributed to Muhammad Ali, the Olympic gold medalist and three-time World Heavyweight Champion boxer. Graceful yet powerful, as his catchphrase implied, Ali became just as famous for his stance against racial intolerance and his outspokenness against American society—in which he felt black men and women were treated as less than equal to whites—as he did for his outstanding success in the ring. Named Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr. when he was born—Ali’s father was named after the ardent 19th-century, Madison County, Ky., abolitionist Cassius Marcellus Clay—Ali’s destiny as social critic seemed fated from birth. Ironically, however, Ali changed his name to Muhammad Ali after embracing the Nation of Islam, insisting that Cassius Clay was his “slave name.”

Ali began his boxing career as a 12-year-old boy in his hometown of Louisville, Ky. When his new bicycle was stolen, he reported the theft to the first police officer he found, crying, and claiming that he would beat up whoever it was who had stolen the bike. As it happened, that officer was Joe Martin, a boxing coach at the Columbia Gym in Louisville. Martin told the distraught boy, “Well, you’d better come back here and learn how to fight,” thus beginning his and Ali’s trainer/boxer relationship.

“I was Cassius Clay then,” Ali said years later in a Sports Illustrated story. “I was a Negro. I ate pork. I had no confidence. I thought white people were superior. I was a Christian Baptist named Cassius Clay.” But by the time Ali was a high school senior he had begun exploring Islam, writing a senior paper on Black Muslims that nearly kept him from passing the class. He boxed as an amateur for six years, winning the Light Heavyweight gold medal in the 1960 Olympics in Rome, turning professional that same year and winning his first Heavyweight Boxing Champion title in 1964 against Sonny Liston. Shortly thereafter he changed his name to Muhammad Ali, symbolizing his new identity as a member of the Nation of Islam.

The shift in Ali’s religious faith came at a volatile time in American civil rights history. Ali became famous after winning the gold medal in Rome, and after winning his first boxing championship and announcing his conversion to Islam, Ali became an outspoken critic of American racial injustice, a message in line with his new Muslim faith. Ali’s obvious prowess in the ring made him a highly visible symbol of black masculinity, and his comments outside the ring became a source of black pride, propelling him into the role of a strong, straight-talking black leader. At a time when violence across the South was raging, Muhammad Ali was speaking out unambiguously against racism, violence, and injustice, and he often preached against social integration as a means to equality: “We who follow the teachings of Elijah Muhammad don’t want to be forced to integrate. Integration is wrong. We don’t want to live with the white man; that’s all.” His rhetoric was often so exaggerated, going so far as to condone lynching as a way to keep the races separate, that he sometimes offended both sides of the race argument, from white supremacists to members of the NAACP.

President Jimmy Carter greets Muhammad Ali at a White House dinner, 1977 (Marion S. Trikosko, photographer, Library of Congress [LC-U9-35102-20], Washington, D.C.)

In 1967, Ali refused to fight in the Vietnam War, claiming conscientious objector status on the basis of his religious beliefs. He later said to a Sports Illustrated reporter, “Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go ten thousand miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs?” As a result of his refusal to serve, Ali lost his boxing license and was stripped of his Heavyweight Boxing Champion title.

In 1970, Ali regained his boxing license, and although he made millions in the ring, he was ostensibly opposed to the sport: “We’re just like two slaves in that ring. The masters get two of us big old black slaves and let us fight it out while they bet: ‘My slave can whup your slave.’ That’s what I see when I see two black people fighting.” Nevertheless, Ali went on to fight in some of the most famous and highly promoted boxing matches in history, such as “The Fight of the Century,” fought in Madison Square Garden against Joe Frasier; “The Rumble in the Jungle,” fought in Zaire, Africa, against George Foreman; and “The Thrilla in Manila,” fought in the Philippines, again against Joe Frasier. Ali lost the first bout by unanimous decision but won the latter two, further cementing his reputation as the epitome of black masculinity.

In time, as public support waned for the war in Vietnam and as the pace of violence against blacks in America slowed, Ali’s antiwhite rhetoric diminished. But his passion for racial justice continued. When asked how he would like to be remembered, he remarked, “As a man who never looked down on those who looked up to him and who helped as many of his people as he could—financial and also in their fight for freedom, justice, and equality. As a man who wouldn’t embarrass them. As a man who tried to unite his people through the faith of Islam that he found when he listened to the Honorable Elijah Muhammad. And if all that’s asking too much, then I guess I’d settle for being remembered only as a great boxing champion who became a preacher and a champion of his people.”

JAMES G. THOMAS JR.

University of Mississippi

Gerald Early, ed., The Muhammad Ali Reader (1998); Thomas Hauser, Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times (1991); Hunt Helm, “The Making of a Champ,” Louisville (Ky.) Courier-Journal (14 September 1997); David Remick, King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero (1998).

Ames, Jessie Daniel

(1883–1972) SOCIAL REFORMER.

Jessie Daniel Ames, born 2 November 1883, had moved three times within Texas by the time she was a teenager. Her father, a stern Victorian eccentric, had migrated from Indiana to Palestine, Tex., where he worked as railroad station master, and in 1893 the Daniels moved to Georgetown, Tex., the site of Southwestern University, from which Ames later graduated.

The brutal Indian Wars and vigilantism of the period created a violent atmosphere, which strongly affected the sensitive young Jessie. A strong-willed child, she had resisted the perfect table manners expected of her and often was sent to the kitchen. In the Daniel kitchen, young Jessie heard about a lynching nearby in Tyler, an event she remembered for years and that influenced her lifelong efforts to abolish lynching.

In June 1905 Jessie Daniel married a handsome army surgeon, Roger Post Ames, who later died in Guatemala. In 1914 she rose to prominence in Texas as an advocate of southern progressivism and woman suffrage. Unlike most suffragists in the early 1920s, she understood the grave injustice against blacks in this country. She served as a vital link between feminism and the 20th-century struggle for black civil rights.

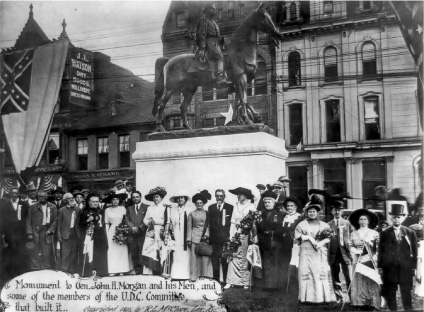

In 1924 she became field secretary for Will Alexander’s Atlanta-based Commission on Interracial Cooperation, and immediately began organizing against lynching in Texas, Arkansas, and Oklahoma. Alexander brought her to Atlanta in 1929 as Director of Women’s Work for the Commission, and in 1930 she founded Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, which within nine years had 40,000 members. Alerted by sympathetic law officers and her contacts in the press when a lynching threatened, Ames contacted women in that county who had pledged to work against violence. Her work was not always appreciated, and opposition came from women as well as men—the Women’s National Association for the Preservation of the White Race claimed that Ames’s women “were defending criminal Negro men at the expense of innocent white girls.”

Ames did not support the federal antilynching law in 1940, believing it to be impractical. She said the bill would pass the House and southern senators would then defeat it. She was soon at odds with her boss, Dr. Alexander, as well as her old allies in the NAACP.

From May 1939 to May 1940 in the South, for the first time since records had been kept, not a single lynching occurred. World War II, however, meant the end of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching, just as it did to the attempt to abolish the hated poll tax in the South. The alliance between women and victimized blacks, which Ames had hoped for, was postponed.

In 1943 Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching was absorbed by the newly formed Southern Regional Council, as was the Interracial Commission. Ames wanted to work for the new agency but found that her services were not needed.

In the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, Ames set about rebuilding her life. Elected superintendent of Christian Social Relations for the Western North Carolina Conference of the Methodist Church, she welcomed the opportunity “to get back into public life and be remembered.” She later returned to Texas and was honored in the 1970s as a pioneer who combined feminism with civil rights activism. Jessie Daniel Ames died on 21 February 1972 at the age of 88.

MARIE S. JEMISON

Birmingham, Alabama

Association of Southern Women for the Prevention of Lynching and Commission on Interracial Cooperation Papers, Trevor Arnett Library, Atlanta University; Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, Revolt against Chivalry: Jessie Daniel Ames and the Women’s Campaign against Lynching (1979); Jessie Daniel Ames Papers, Texas Historical Society, Dallas, Texas State Library, Austin, and Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; Jon D. Swartz and Joanna Fountain-Schroeder, eds., Jessie Daniel Ames: An Exhibition at Southwestern University (1986).

Atkinson, Ti-Grace

(b. 1939) FEMINIST.

Ti-Grace Atkinson captured public attention between 1966 and 1972 as one of the most articulate and radical speakers for the women’s movement in the United States. She was a protégé of Betty Friedan, who promoted her in the National Organization for Women (NOW) because her “lady-like blond image would counter-act the man-eating specter.” Yet Atkinson, who was described by the media as “softly sexy,” “tall,” and “elegantly feline,” came to stand for all that Friedan saw as most damaging to the movement: total separation from men, advocacy of abortion on demand, and the destruction of marriage and the family.

Atkinson was born in 1939 to an established Baton Rouge family. Had she remained at home, she might have become the family eccentric, an acceptable, though not desirable, role for southern women of her class. But she was one of those southerners whom Roy Reed described as born afire, who spend their days looking elsewhere for something to ease the burning. Although Atkinson virtually disowned and never discussed her southern upbringing, she always insisted that interviewers record her name as the Cajun “Ti-Grace.”

Married at 17, Atkinson went to Philadelphia. By the time she was divorced five years later, she had earned a B.F.A. degree at the University of Pennsylvania and was establishing a career as an art critic, writing for Art News and acting as the founding director of the Philadelphia Institute for Contemporary Art. Then Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex converted her to a new philosophy. In 1966 Atkinson joined the nascent NOW, where her appearance, manners, and genteel Republican connections were put to use in national fund-raising.

A year later, Atkinson moved to New York City to pursue graduate study in political philosophy at Columbia University. As president of the local NOW chapter, she generated conflict within the group with her demands for changes not only in the organization’s goals and programs but also in its internal structure. Failing to achieve her aims within NOW, she resigned in 1968 to start the October 17th Movement, later modestly renamed the Feminists—a small group of 15 to 20 women who were to separate totally from men. Although frequently described as a lesbian, Atkinson was in fact an advocate of celibacy. It was, she acknowledged, a model for which most women were not ready.

Atkinson’s distinctive position in the women’s movement was characterized by her exceptional intelligence, her uncompromising radicalism, and her willingness to follow any position to its logical conclusion. She took the Mafia as a model of resistance, living outside the law, and formed an alliance with the Italian American Civil Rights League of reputed mobster Joseph Colombo. This affiliation was widely attacked, and on 6 August 1971 Atkinson separated herself from the rest of the women’s movement.

Despite this breach, in November 1971 she helped organize the Feminist Party, which attempted to get the major political parties to incorporate feminist positions into their 1972 platforms. After publication in 1974 of Amazon Odyssey, a collection of her speeches and other writings from 1967 to 1972, Atkinson faded from public view. She continues to live in New York City.

JORDY BELL

Croton-on-Hudson, New York

Ti-Grace Atkinson, Amazon Odyssey: The First Collection of Writings by the Political Pioneer of the Women’s Movement (1974); Maren Lockwood Carden, The New Feminist Movement (1974); Betty Friedan, New York Times Magazine (4 March 1973); Martha Weinman Lear, New York Times Magazine (10 March 1968); Newsweek (23 March 1970).

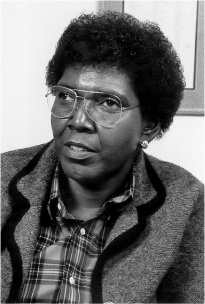

Baker, Ella Jo

(1903–1986) CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIVIST.

Ella Jo Baker, the daughter of Georgianna and Blake Baker, was born in 1903 in Norfolk, Va. When she was seven, Baker’s family moved to Littleton, N.C., to live with her maternal grandparents, who owned a plantation where they had previously worked as slaves. The absence of adequate public school for blacks in rural North Carolina and her mother’s concern that she be properly educated resulted in Baker’s attending Shaw University in Raleigh. There she received both her high school and college education. Following her graduation in 1927, she moved to New York City to live with a cousin, working as a waitress and then in a factory.

The product of a southern environment in which caring and sharing were facts of life and of a family in which her grandfather regularly mortgaged his property in order to help neighbors, Baker soon became involved in various community groups. In 1932 she became the national director for the Young Negroes Cooperative League and the office manager of the Negro National News. Six years later, she began her active career with the NAACP, working initially as a field secretary in the South. In 1943 she was appointed national director of the branches for the NAACP. In both capacities Baker spent long periods in southern black communities, where her southern roots served her well. Her success in recruiting southern blacks to join what was considered a radical organization in the 1930s and 1940s may be attributed, in part, to her being a native of the region and, therefore, able to approach southern people. Baker, who neither married nor had children of her own, left active service in the NAACP in 1946 in order to raise a niece. A short while later she reactivated her involvement with the NAACP, becoming president of the New York City chapter in 1954.

In 1957 Baker went south again, this time to work with the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), a newly formed civil rights organization. The student sit-in movement of the 1960s protested the refusal of public restaurants in the South to serve blacks and resulted in Baker’s involvement in still another civil rights group. As the coordinator of the 1960 Nonviolent Resistance to Segregation Leadership Conference, which brought together over 300 student sit-in leaders and resulted in the formation of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), Baker is credited with playing a major role in SNCC’s founding. Severing her formal relationship with SCLC, she worked with the Southern Conference Educational Fund. In recognition of her contribution to improving the quality of life of southern blacks and to the founding of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, she was asked to deliver the keynote address at its 1964 convention in Jackson, Miss.

Baker spent the remainder of her life in New York City, where she served as an adviser to a number of community groups. Prior to the release of Joanne Grant’s film Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker, few people outside of the civil rights movement in the South knew about Baker’s long career as a civil rights activist, but since then a number of leadership programs and grassroots organizations, such as the Children’s Defense Fund’s Ella Baker Child Policy Training Institute and the Bay Area’s Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, have been named in her honor. Nevertheless, she is probably less well known than many other civil rights workers, because she was a woman surrounded by southern men, primarily ministers, who generally perceived women as supporters rather than as leaders in the movement, and because of her own firm belief in group-centered rather than individual-centered leadership.

SHARON HARLEY

University of Maryland

Ellen Cantarow and Susan Gushee O’Malley, Moving the Mountain: Women Working for Social Change (1980); Clay-borne Carson, In Struggle: sncc and the Black Awakening of the 1960s (1981); Joanne Grant, Ella Baker: Freedom Bound (1999); Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (2003).

Bethune, Mary McLeod

(1875–1955) EDUCATOR.

On 10 July 1875, future educator, federal government official, and club woman Mary McLeod Bethune was born near Mayesville, S.C., one of 17 children born to former slaves and farmworkers Samuel and Patsy (McIntosh) McLeod. In 1882 Bethune left behind many of her farm chores to attend the newly opened Presbyterian mission school for blacks near Mayesville. With the help of a scholarship, she left South Carolina in 1888 and continued her education at Scotia Seminary (later Barber-Scotia College) in Concord, N.C., completing the high school program in 1892 and the Normal and Scientific Course two years later. Hoping to become a missionary in Africa, she studied at the Moody Bible Institute in Chicago, but in 1895 the Presbyterian Mission Board turned down her application for a missionary post.

A disappointed Mary McLeod returned to her native South Carolina and began her first teaching job at Miss Emma Wilson’s Mission School, where she had once been a student. Shortly thereafter, the Presbyterian Board appointed her to a teaching position at Haines Normal and Industrial Institute, later transferring her to Kindell Institute in Sumter, S.C.

Following her marriage to Albertus Bethune in May 1898, she and her husband moved to Savannah, Ga., where their only child, Albert McLeod Bethune, was born in 1899. Later that year, the family moved to Palatka, Fla., where she established a Presbyterian missionary school. Five years later, after separating from her husband, Bethune realized her lifelong ambition to build a school for black girls in the South and with her son moved to Daytona Beach, Fla., where in October 1904 the Daytona Literary and Industrial School for Training Negro Girls opened with Bethune as its president. Like most black educators in the post-Reconstruction South, Bethune emphasized industrial skills and Christian values and appealed to both the neighboring black community and white philanthropists for financial support. As a consequence of Bethune’s unwavering dedication, business acumen, and intellectual ability, the Daytona Institute grew from a small elementary school to include a high school and a teacher training program. In 1923 Bethune’s school merged with Cookman Institute, a Jacksonville, Fla., college for men, and became the Daytona-Cookman Collegiate Institute. Six years later, the school’s name was changed to Bethune-Cookman College, in recognition of the important role that Mary McLeod Bethune had played in the school’s growth and development.

As an educator in the South, Bethune had concerns that extended beyond campus life. In the absence of a municipally supported medical facility for blacks, the Daytona Institute, under Bethune’s guidance, maintained a hospital for blacks from 1911 to 1927. During much of this same period she also operated the Tomoka Mission Schools, for the children of black families working in the Florida turpentine camps. Ignoring threats made by members of the Ku Klux Klan, Bethune organized a black voter registration drive in Florida, decades before the voter registration drives of the 1960s. As a delegate to the first meeting of the Southern Conference for Human Welfare, Bethune voiced her opposition to degrading southern racial customs.

Bethune joined and held official positions in a number of organizations, but she is best known among club women and the public at large for her monumental work with the National Council of Negro Women, which she founded at age 60 in 1935, serving as its president until 1949. Dedicated to meeting the myriad needs of blacks in all walks of life, the council grew under Bethune’s leadership to become the largest federation of black women’s clubs in the United States. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., and with chapters throughout the country and abroad, this association published the Aframerican Woman’s Journal, established health and job clinics throughout the South, and educated a number of black youths from poor families in the South.

In 1935 President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed Bethune as one of his special advisers on racial affairs, and four years later she served as the director of black affairs for the National Youth Administration. In May 1955, at the age of 79, one of the South’s most well-known women died. The unveiling of a statue of Bethune in a federal park located in the nation’s capital in 1974 and the opening of the Mary McLeod Bethune Museum and Archives for Black Women’s History in Washington, D.C., in 1979 are lasting testaments to Bethune’s intelligence and determination.

SHARON HARLEY

University of Maryland

James J. Flynn, Negroes of Achievement in Modern America (1970); Rackham Holt, Mary McLeod Bethune: A Biography (1964); Barbara Sicherman and Carol Hurd Green, eds., Notable American Women: The Modern Period: A Biographical Dictionary (1980); Emma Sterne, Mary McLeod Bethune (1957).

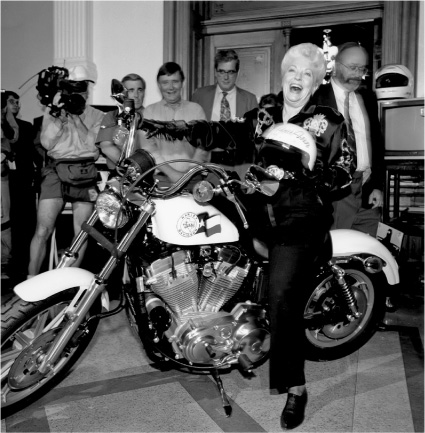

Boggs, Lindy

(b. 1916) POLITICIAN.

Marie Corinne Morrison Claiborne (“Lindy”) was born 13 March 1916 at Brunswick Plantation, near New Roads, in Pointe Coupee Parish, La. She graduated from St. Joseph’s Academy at New Roads in 1931 and earned her B.A. degree from Sophie Newcomb College of Tulane University in 1935, after which she became a teacher. She married Thomas Hale Boggs Sr., and, after his presumed death in an airplane that disappeared, she was selected in a special election in 1973 to succeed him as Democratic U.S. representative from the Second District in New Orleans. Boggs was elected, with 82 percent of the vote, to a full term in 1974 and served nine terms. Boggs had 30 years of behind-the-scenes political activism before her election, working with her husband to raise money, run campaigns, and manage his Washington office.

While in Congress, Boggs served on the House Appropriations Committee and the Select Committee on Children, Youth, and Families, and she chaired the Joint Committee on Bicentennial Arrangements and the Commission on the Bicentenary of the U.S. House of Representatives. Boggs promoted legislation on civil rights, children and families, and equal pay for women. She was one of the founders of the Women’s Congressional Caucus and was the first woman to chair the Democratic National Convention. President Bill Clinton appointed her the U.S. Ambassador to the Vatican, where she served from 1997 to 2001. In 2006 Boggs received the Congressional Distinguished Service Award. Her political and family life is documented in Lindy Boggs: Steel and Velvet, a 2007 film by Louisiana Public Broadcasting and Blackberry Films.

CHARLES REAGAN WILSON

University of Mississippi

Lindy Boggs, with Katherine Hatch, Washington through a Purple Veil: Memoirs of a Southern Woman (1994); Thomas H. Ferrell and Judith Haydel, Louisiana History (Fall 1994).

Brown, Charlotte Hawkins

(1883–1961) ACTIVIST AND EDUCATOR.

Regarded as the “First Lady of Social Graces,” Charlotte Hawkins Brown spent more than 50 years guiding the education and social habits of southern black youth at her Palmer Memorial Institute in North Carolina. The descendant of slaves, Brown was born Lottie Hawkins on 11 June 1883 in Henderson, N.C. Lottie’s grandmother, Rebecca Hawkins, descended from English navigator Sir John D. Hawkins. At an early age, Brown saw the importance of education and cultural aspirations as embodied in her mother and grandmother. Lottie’s 18-member family moved to Cambridge, Mass., in 1888 for better social, economic, and educational opportunities. At Cambridge, the young Brown attended the Allston Grammar School and cultivated a friendship with Alice and Edith Longfellow, children of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, who lived in her neighborhood near Harvard University. Demonstrating early proclivities for leadership, Brown, at age 12, organized her church’s Sunday school kindergarten department. At Cambridge English High School, moreover, she proved herself an excellent scholar and artist, rendering several crayon portraits of classmates. Considering “Lottie” too ordinary, she changed her name to Charlotte Eugenia Hawkins upon graduation. Observing Brown in 1900 reading Virgil while babysitting two infants, Alice Freeman Palmer, humanitarian and president of Wellesley College, became her benefactor.

Influenced by educator and power broker Booker T. Washington, Brown sought to teach blacks in the South. To further this goal, she enrolled, with the help of Palmer, in the State Normal School at Salem, Mass., in the fall of 1900. Having been approached by a field secretary of the American Missionary Association, a white-led group that administered and financed southern black schools, Brown eagerly accepted an invitation to teach in her native state. Barely 18 years old, Brown emerged from a Southern Railway train in the fall of 1900, where she was confronted with the unfamiliar terrain of Guilford County, N.C. Suspending her junior college education at State Normal School, she began her first teaching job at Bethany Institute in Sedalia—a small, dilapidated, rural school for African Americans. Securing money from northern friends and donations from the Sedalia community, Brown soon raised funds to erect a campus with more than 200 acres and two new buildings. Alice Freeman Palmer Institute, named in honor of her benefactor, opened on 10 October 1902. It was later renamed the Alice Freeman Palmer Memorial Institute upon Palmer’s death.

Distinguished among its contemporaries, Brown’s private finishing school for rural African Americans provided college preparatory classes for upper-level high school students. Such instruction fitted the school’s dual ambitions: to undo common assumptions of African American inferiority and to provide an expansive education beyond vocational studies. At Palmer, classes included art, math, literature, and Romance languages.

In addition to academic training, Brown outlined an exacting program of etiquette, involving lessons in character and appearance, for black boys and girls. Brown expected her students to abide by a strict code of Victorian moral conduct. She worked to smooth “the rough edges of social behavior” by producing graduates who were educationally sound, religiously sincere, and “culturally secure.” This cultural regime, in part, took the form of small discussion groups for boys and girls, the boys led by an adult male counselor and the girls by an adult female counselor, in which students received individual attention in matters of etiquette. In one boys’ session, discussion centered on the best manner in which to obtain “culture,” along with clean minds and bodies. Students also participated in “wholesome” fitness activities designed to nurture habits of self-reliance, self-control, and fair play. Palmer girls played basketball and volleyball. The young men’s sports repertoire was more expansive and included basketball, football, baseball, and track and field.

Perhaps Brown’s most noted contribution to her student’s cultural education was her etiquette manual, The Correct Thing to Do, to Say, to Wear. In it, she succinctly defined good manners for boys and girls, at home and outside of the home. Proper introductions, boy-girl relationships, and dress were also addressed. Palmer’s curriculum and Brown’s writings mirrored her race philosophy, which sought a holistic education for black youth based on the uplift of the individual. Charlotte Hawkins Brown and fellow black educators Mary McLeod Bethune and Nannie Helen Burroughs became collectively known as the “Three B’s of Education,” stressing liberal arts and cultural training for race uplift. The school’s political and cultural legacy largely hinges on Palmer’s credo, “Educate the individual to live in the greater world.” Brown’s shepherding of Palmer, which survived a major fire in 1917, ended in 1952. She died in 1961 and is buried on the Palmer campus, now a state historic site.

ANGELA HORNSBY-GUTTING

University of Mississippi

Charlotte Hawkins Brown, The Correct Thing to Do, to Say, to Wear (1941); Colonel Hawkins Jr., in The Heritage of Blacks in North Carolina, vol. 1, ed. Philip N. Henry and Carol M. Speas (1990); Tera Hunter, Southern Exposure (September/October 1983); Marsha Vick, in Notable Black American Women, ed. Jessie Carney Smith (1992); Charles Wadelington, Tar Heel Junior Historian (1995); Charles W. Wadelington and Richard F. Knapp, Charlotte Hawkins Brown and Palmer Memorial Institute: What One Young African American Woman Could Do (1999).

Burroughs, Nannie Helen

(1879–1961) EDUCATOR AND SOCIAL ACTIVIST.

As a church and organization leader, school founder and educator, women’s advocate and race champion, Nannie Helen Burroughs was a pragmatic warrior and outspoken public intellectual who defied conventional female confinements of her era. Through her newspaper commentary, speeches, and writings, she inserted herself into the male-centered discourse on race advancement. Her work paralleled that of better-known black women predecessors and contemporaries, including Annie Julia Cooper, Mary Church Terrell, and Mary McLeod Bethune, and her accomplishments and zeal for race uplift were equally impressive. She brought into the public sphere a deep concern for black workers who lacked “social or economic pull” and a belief in self-help that caused people to compare her to Booker T. Washington. Burroughs, however, was more like W. E. B. Du Bois in her belief that blacks must demand their full rights, including woman suffrage, and must keep agitating for justice. “Hound dogs are kicked, not bull dogs,” she wrote.

Burroughs’s unique contribution to black female empowerment was in her understanding that black women needed both “respectability”—sometimes oversimplified by scholars as a middle-class notion—and economic self-sufficiency. In her view, one was not possible without the other. Her school, the National Training School for Women and Girls in Washington, D.C., was the realization of her dream of providing a practical education that would make black women economically self-sufficient and beyond spiritual and moral reproach. It was founded in 1909 with the help of the Women’s Auxiliary of the National Baptist Convention, where Burroughs was the long-serving corresponding secretary. Graduates were expected to become community-minded wage earners who would counter the prevailing negative stereotypes of the black race—particularly of its women. Burroughs’s grand vision was reflected in the fact that in naming the school she left out “Baptist,” although she was supported by that denomination, and included “National” to signify the school’s nonsectarianism and her own independence. Women wrote to Burroughs from across the nation seeking admission for themselves or their daughters and expressing delight in the prospect of living in such a protective enclave and reaping its many benefits.

Burroughs believed that women were the linchpins of race progress, and the curriculum stressed Christian-inspired precepts about the dignity of all work. By training black women to be skilled workers and “professionalizing” their work, including domestic work, she sought to raise women’s self-esteem, race pride, and wages. Her school offered a mandatory black history course, courses in music, public speaking, secretarial skills, the Bible, and hygiene, plus nontraditional courses in shoe repair and printing. Using student labor, successful commercial ventures such as the Sunlight Laundry were launched. The school’s creed—the three B’s, “the Bible, the Bath, and Broom, clean life, clean body, clean house”—was infused into every aspect of school life. So was Burroughs’s defiant certitude about black female education, captured in the famous declaration that became the school’s motto: “We specialize in the wholly impossible.”

In establishing the National Training School for Women and Girls (renamed the National Trade and Professional School for Women and Girls in 1939), Burroughs challenged the male leadership of the National Baptist Convention, which was wary of women leaders, and Booker T. Washington, who opposed locating black schools outside of the South for fear of losing support from white northerners. Burroughs realized the importance of having a black female presence in the nation’s capital and used that visibility to attract a national and international student body. In addition to her long tenure as founder and principal of the National Training School for Women and Girls, Burroughs helped to organize the National Association of Wage Earners in 1921 to support better wages and living conditions for domestic workers.

Following her death in 1961, the school was renamed in her honor, and it continues as a kindergarten through sixth grade Christian day school on that same Washington, D.C., hillside from which Burroughs looked out into the world and sought to change it.

AUDREY THOMAS MCCLUSKEY

Indiana University

Sharon Harley, Journal of Negro History (Winter/Autumn 1996); Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (1993); Audrey Thomas McCluskey, Signs (Winter 1997); Nannie Helen Burroughs Papers, Library of Congress Manuscript Division; Victoria W. Wolcott, Journal of Women’s History (Spring 1997).

Carter, Rosalynn

(b. 1927) FORMER FIRST LADY OF THE UNITED STATES.

Like First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, Rosalynn Smith Carter played a major role in national affairs during her tenure in the White House. Since then, she has acted as a partner in many of former president Jimmy Carter’s political and business endeavors, and she has strongly promoted mental health and women’s rights issues. Her autobiography, First Lady from Plains (1984), has been warmly received by political analysts and literary critics.

Born in Plains, Ga., on 18 August 1927, Rosalynn Smith enjoyed a relatively carefree childhood until her father died of leukemia when she was 13. The following years were lean ones for her family—her mother, Allie Smith, was forced to make ends meet by taking in sewing and selling extra eggs and butter from the family’s farm. Rosalynn helped her mother by working part time after school in a beauty salon. After her graduation from Plains High School as valedictorian of her class, Rosalynn Smith entered Georgia Southwestern College, a two-year college in Americus, Ga. In 1944, while visiting her best friend, Ruth Carter, Rosalynn spied and admired a picture of Ruth’s brother Jimmy, a U.S. Naval Academy student. The couple married two years later. Ambitious and intelligent, she viewed her husband’s naval career as her ticket out of Plains. Jimmy Carter’s career took the young couple as far as Hawaii before his father died in 1953, when he resigned his commission to return to Plains to take over the family peanut business. Although she opposed his decision to return to Plains, Rosalynn Carter soon plunged into keeping books for the business, raising her family, and, eventually, taking accounting courses.

Politics has been the lifeblood of the Carter family. Rosalynn Carter’s first taste of public life occurred in the early 1960s during her husband’s stint on the local school board. His liberal political stances often brought threats to her family and the peanut business from area residents. In Jimmy Carter’s 1962 bid for the Georgia state Senate, Rosalynn Carter handled all of his campaign correspondence. By 1970, when Carter was elected governor of Georgia, she had gained experience and, thereby, a reputation as a “steel magnolia”—a warm, gracious woman who was also politically astute. Eager to move beyond the boundaries of the governor’s mansion, she worked with the Georgia Governor’s Commission to Improve Service for the Mentally and Emotionally Handicapped, as a volunteer at the Georgia Regional Hospital in Atlanta, and as honorary chairman of the Georgia Special Olympics, and over the next four years she helped establish 134 day-care centers for the mentally retarded.

From 1973 to 1976 Rosalynn Carter campaigned independently in 96 cities and 36 states in Governor Carter’s bid for the presidency. Once the Carters reached the White House, the new first lady took an active interest in national policy making, attending cabinet meetings, holding weekly working lunches with President Carter, heading a diplomatic mission to South America, and attending the Camp David Mideast Peace Summit. She continued to pursue mental health reform on a national level while serving on the President’s Commission on Mental Health and on the Board of Directors of the National Association of Mental Health. Her support of the Equal Rights Amendment won her a merit award from NOW.

Rosalynn Carter, first lady of the United States, 1977–81 (Carter Presidential Library, Atlanta)

Rosalynn Carter again took to the campaign trail in President Carter’s reelection drive of 1980. His defeat was particularly devastating for her, and after two decades of public service she initially found it difficult to adjust to private life. After her return to Plains, she renewed her focus on mental health and women’s rights. Numerous speaking engagements and promotions of her autobiography, First Lady from Plains, and of Everything to Gain: Making the Most of the Rest of Your Life, written with her husband, allowed Rosalynn Carter to talk publicly and candidly about her life as first lady and to raise social and political issues of concern to her. In 1982 the Carters founded the Carter Center, a not-for-profit, nongovernmental organization whose mission it is to “wage peace, fight disease, and build hope” worldwide. She has worked to promote the mental health and well-being of individuals, families, and caregivers through the Rosalynn Carter Institute for Caregiving at Georgia Southwestern State University, an institute founded in her honor on the campus of her alma mater in Americus, Ga., and she continues to contribute her time and efforts to Habitat for Humanity, a network of volunteers who build homes for the needy, and Project Interconnections, a public/private nonprofit partnership to provide housing for homeless people who are mentally ill. Rosalynn Carter has received countless honors for her work. In August 1999 President Clinton awarded Rosalynn and Jimmy Carter the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honor, and in 2001 Rosalynn was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame.

ELIZABETH MCGEHEE

Washington Post

Carl Sferrazza Anthony, in American First Ladies: Their Lives and Legacy, ed. Lewis L. Gould (2001); Patricia A. Avery, U.S. News and World Report (25 June 1984); Rosalynn Carter, First Lady from Plains (1984); Phil Gailey, New York Times Book Review (15 April 1984); Who’s Who in America (1980–81).

Chesnut, Mary Boykin

(1823–1886) DIARIST AND AUTHOR. Mary Boykin Miller Chesnut was born 31 March 1823 in Stateboro, S.C., the eldest child of Mary Boykin and Stephen Decatur Miller, who had served as U.S. congressman and senator and in 1826 was elected governor of South Carolina, as a proponent of nullification. Educated first at home and then in Camden schools, Mary Miller was sent at age 13 to a French boarding school in Charleston, where she remained for two years, broken by a six-month stay on her father’s cotton plantation in frontier Mississippi. In 1838 Miller died and Mary returned to Camden. On 23 April 1840 she married James Chesnut Jr. (1815–85), the only surviving son of one of South Carolina’s largest landowners.

Chesnut spent most of the next 20 years in Camden and at Mulberry, her husband’s family plantation. When James Chesnut was elected to the Senate in 1858, his wife accompanied him to Washington, where they began friendships with many politicians who would become the leading figures of the Confederacy, among them Varina and Jefferson Davis. Following Lincoln’s election, James Chesnut returned to South Carolina to participate in the drafting of an ordinance of secession and subsequently served in the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States of America. He served as aide to Gen. P. G. T. Beauregard and President Jefferson Davis, and he achieved the rank of general. During the war, Mary accompanied her husband to Charleston, Montgomery, Columbia, and Richmond, her drawing room always serving as a salon for the Confederate elite. From February 1861 to July 1865 she recorded her experiences in a series of diaries, which became the principal source materials for her famous portrait of the Confederacy.

Following the war, the Chesnuts returned to Camden and worked unsuccessfully to extricate themselves from heavy debts. After a first abortive attempt in the 1870s to smooth the diaries into publishable form, Mary Chesnut tried her hand at fiction. She completed but never published three novels and then in the early 1880s expanded and extensively revised her diaries into the book now known as Mary Chesnut’s Civil War (first published in truncated and poorly edited versions in 1905 and 1949 as A Diary from Dixie).

Although unfinished at the time of her death on 22 November 1886, Mary Chesnut’s Civil War is generally acknowledged today as the finest literary work of the Confederacy. Spiced by the author’s sharp intelligence, irreverent wit, and keen sense of irony and metaphorical vision, it uses a diary format to evoke a full, accurate picture of the South in civil war. Chesnut’s book, valued as a rich historical source, owes much of its fascination to its juxtaposition of the loves and griefs of individuals against vast social upheaval and much of its power to the contrasts and continuities drawn between the antebellum world and a war-torn country.

ELISABETH MUHLENFELD

Sweet Briar College

Mary A. DeCredico, Mary Boykin Chesnut: A Confederate Woman’s Life (1996); Elisabeth Muhlenfeld, Mary Boykin Chesnut: A Biography (1981); C. Vann Woodward, ed., Mary Chesnut’s Civil War (1981); C. Vann Woodward and Elisabeth Muhlenfeld, eds., The Private Mary Chesnut: The Unpublished Civil War Diaries (1985).

Conroy, Pat

(b. 1945) WRITER.

Pat Conroy has spent his career crafting personal trauma and abuse into rich, romantic, and often painfully autobiographical fiction. Along the way, he has become famous nearly as much for his contentious battles and reconciliations with his alma mater and his father as for his artistic and phenomenal commercial accomplishments.