Chapter 4

The Rising Generation

Why Rising?

We begin this section on the who of family wealth with the rising generation. We do so purposefully. Most advisers and family members focus their attention on parents or grandparents. Explicitly or not they follow the supposed Golden Rule: whoever has the gold rules. That’s usually the senior generation, the generation that has already risen to the height of family authority.

As an aside, if you are an adviser, ask yourself three questions: (1) Who is paying my fees? (2) Who do I consider my client? (3) Who is advocating for the growth and well-being of the rising generation? If the answers to those first two questions are, “the senior generation,” and the third, “no one,” then the family you are serving is heading for grief. If the answer to that third question is “someone other than me,” then they likely won’t be your clients for long.

If you are a member of the rising generation in a family, you know that you are the family’s future. You hold the keys to the family’s true wealth.

That’s why we use the term rising. More often, people refer to the “next” generation in families with wealth or a family business. We recommend that you eliminate the term next from your vocabulary, at least as it refers to generations. “Next” puts the emphasis on what came first and, again, that’s parents or the wealth creators; they are the important ones; everyone else is just next.

In contrast, we believe that each generation has its promise. Each generation has its ability to rise. This capacity is most evident when members of the rising generation are young adults or people in their 20s or 30s. But “rising” also does not need to be limited to age or demography (e.g., millennials or Gen Xers). Many times, especially within families with wealth, people in their 40s, 50s, or 60s who never had a chance to fully establish their own identities are taking hold of the opportunity to rise.

We are now going to focus on rising in early adulthood; we will return at the end of the chapter to rising in the middle passage of life.

The Effects of the Black Hole

Rising and growing is a part of human life, whether you live amid great financial capital or not. But, as we just mentioned, sometimes the presence of great financial capital can impede the natural tendency to rise.

We capture the source of this danger in an image we call the “Black Hole.” If you come from a family of significant wealth, think for a moment about your history. Is there someone who looms large, as the creator of the family’s good fortune? Do you as a family tell admiring stories about this person’s trials and triumphs? Do his or her values and views dominate family decisions? Do his or her decisions about trusts or partnerships still shape family members’ choices about how they live their lives?

If so, your family is not unusual. The larger-than-life founder is a fixture in most families with significant wealth. Such a founder and his or her dream can serve as a sun to the entire family, shining upon its members, making possible good things, and giving the family a sense of belonging and importance.

At the same time, it is precisely this amazing founder and his or her dream that we call the Black Hole. For next to this person’s accomplishments and dreams, everyone else in the family, for generations, can seem to shrink to insignificance.

The fundamental question that faces any member of the rising generation, then, is, “How can I escape the gravity of the Black Hole and establish my own sense of identify and pursue my own dreams?”

To begin to think through that question, it is important to be clear about yourself and about the effects that the Black Hole may already have on you. Here are some characteristics that we often see crop up in families with significant wealth. As you read through them, do any of them describe you or members of your family?

- The Dutiful Steward: stewardship and tradition are good things. But sometimes they seem to take the place of everything else. If you are only a steward, what are you? Whose dream are you stewarding? What about your own dreams?

- The Meteor: How many times have we met members of the rising generation who tell us that they found out about the staggering size of their families’ wealth when they mistakenly got financial statements in the mail! The effect of such disclosures can be like a meteor crashing into the recipient’s atmosphere. The member of the rising generation can be knocked totally off course, wondering who he or she is and what path in life is worth pursuing. The effect of the meteor is even more powerful if the Black Hole has silenced all discussions of family wealth before then.

- Froggy: the proverbial frog placed in a pot of hot water jumps right out, while one in a slowly heated pot gets cooked. Are you being slowly cooked by the attractions—nice houses, great vacations, lots of toys—of the Black Hole? Do you want to jump but worry about how cold it might be outside?

- The Parallel Universe: We have known parents who, in a mistaken attempt perhaps to free themselves from the Black Hole’s gravity, purposefully brought their children up shopping at Goodwill or Salvation Army, even though they had millions of dollars in financial assets. When, inevitably, those members of the rising generation found out, they felt betrayed, as though their childhood had been lived in a parallel universe. They were left wondering, perhaps permanently, “What’s real?”

- The Anxious Heir: “Compared to the founder, how can I ever measure up?” That’s a worry many members of the rising generation nurse in their hearts. It can lead to feeling always unsure about your own ability to make good decisions, trust others, and manage your own life.

- Mr. Reputable: A common variant of this anxiety takes the form of worrying about the family’s reputation and severely limiting your own choices—of where to live, what to do, which friends to have—with a view toward “keeping up the good name.”

- The Grand Giver: Some members of the rising generation seek to blast out of the orbit of the Black Hole by openly repudiating their family’s wealth, perhaps by giving it all away philanthropically. Such giving may do some good in the world, but it can lead to deep regrets and broken family relationships.

The Challenge

The solution to the problem posed by the Black Hole is psychological, captured in the word “individuation.” This means establishing your own sense of identity as an individual with skills, knowledge, character, and purpose. It means separating your identity from the identities of the founder, your parents, teachers, and other important influencers on your life.

Individuation takes place within the context of development. To provide an outline of human development, we have summarized the psychoanalyst Erik Erikson’s account of its main stages. Each stage is characterized by a dilemma and activities appropriate to addressing that dilemma:

-

Infant

Trust vs. Mistrust

Needs maximum comfort with minimal uncertainty to trust herself, others, and the environment.

-

Toddler

Autonomy vs. Shame and Doubt

Works to master physical environment while maintaining self-esteem.

-

Preschooler

Initiative vs. Guilt

Begins to initiate, not imitate, activities; develops conscience and sexual identity.

-

School-Age Child

Industry vs. Inferiority

Tries to develop a sense of self-worth by refining skills.

-

Adolescent

Identity vs. Role Confusion

Tries integrating many roles (child, sibling, student, athlete, worker) into a self-image under role model and peer pressure.

-

Young Adult

Intimacy vs. Isolation

Learns to make personal commitment to another as spouse or partner.

-

Middle-Age Adult

Generativity vs. Stagnation

Seeks satisfaction through productivity in career, family, and civic interests.

-

Older Adult

Integrity vs. Despair

Reviews life accomplishments, deals with loss and preparation for death.

Before going on, ask yourself these questions:

- What stage of adult development are you in right now?

- What stage of development are your significant family members in?

- What special challenges are you experiencing in your present stage of development?

- What did you do that was most helpful in making life transitions in the past?

- You could better enjoy your present stage of life if you would continue . . . ?

- You could better enjoy your present stage of life if you would stop . . . ?

- You could better enjoy your present stage of life if you would start . . . ?

Individuation is an activity that transcends several of the stages of life, especially from childhood through middle age. Very importantly, individuation does not mean individualism—losing all connection to where you came from and other members of your family. It means maintaining a mature connection with others. It involves a balance of separateness and connectedness, or independence and interdependence. That’s a balance that each one of us must find, with wealth or without wealth. It is a basic human challenge.

To that basic human challenge add the special factor or special need of family wealth. Family financial capital has a way of emphasizing connectedness. If you have successful parents, it can be hard to get out from under their shadow. If your family is famous, it can be hard to establish your own name. If you grow up surrounded by trusts and businesses and the like, you may find it tough to make your own choices about important topics in your life.

In truth, at different points in your life, the founding dream may appropriately loom larger, at other points smaller. It is never possible—or even desirable—for either part, your dream or your family’s connectedness, to vanish completely.

Many members of the rising generation tell us that their parents worry that they will become entitled. But the real cause of entitlement is the failure of the rising generation to individuate. The core of entitlement is failing to see yourself as a capable, independent person. The antidote to entitlement is individuation.

Meeting the Challenge

Rising is a life’s work. Here are two suggestions on how to continue or begin the process:

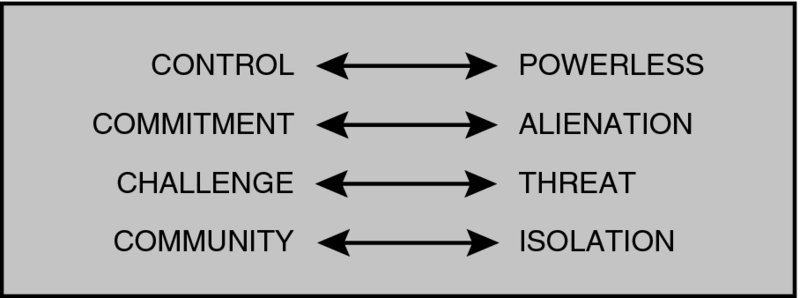

- Ask yourself, “In which situations have I felt truly in control, positively committed, gladly challenged, and in community with others?” These “Four Cs” indicate a place of self-centeredness and self-efficacy. Recognizing where you feel the Four Cs can help you seek out similar situations in the present and future (see Figure 4.1). (For more on the Four Cs see the Conclusion.)

- Next, think about what activities you are good at. What do you esteem about yourself? Where have you enjoyed the greatest success? You decide what success means. Once you’ve identified these activities, look behind them: what strengths have allowed you to enjoy this success?

Figure 4.1 The Four Cs

These are questions aimed at self-knowledge. But self-knowledge does not come only, or for all people, from reflection. It can also come from action. It is important to test your self-understanding in practice.

The areas that we have found most important in that testing are work, relationships, and communication (especially with other family members, including parents). If there are any red flags that our experience has taught us to look out for in families with significant wealth, they are when children grow up without any true sense of work (done by themselves or their parents), without lasting and trusting relationships, and without open and honest communication in the family.

In the pages that follow you will find specific chapters devoted to the subjects of work, friendships, and communication. Here we will summarize a few points about each especially relevant to the rising generation.

When it comes to work, look for activities that challenge you and test your abilities, that require your dedication, and that also meet the true needs of others. That work may be for pay; it may be volunteer. It may be part- or full-time. The key is that in having to dedicate ourselves at least in part to others’ needs, we learn a great deal about our own strengths.

If you are growing up in the context of an operating business controlled by your family, there may be a strong incentive for you to work in that business. This can be a wonderful experience, but we recommend that you pursue it only after you have had significant experience, say, three to five years, testing yourself and growing through work someplace else. You will make contacts and learn skills and knowledge perhaps unavailable at home, making you even more valuable to the family enterprise. Further, you (and your family) will never feel bedeviled by the question of whether you could make it on your own outside the proverbial nest.

As for relationships, we recommend that members of the rising generation (or indeed any generation) cultivate relationships with people who:

- Affirm your strengths

- Share your dreams

- Are positive and forward-focused

- Challenge you to be the best you can be

Think about your own close friendships or other relationships. Can you see elements of these characteristics in your friends or partners? One of the main concerns voiced by members of the rising generation within families with wealth is that they fear that prospective friends or partners will see them only for their money. This is a valid concern. The response to this challenge is not to hide your money, much less to flaunt it, but to go beyond the money in evaluating your prospective friends. If they do the four things listed above, you will find ways together to deal with the money.

Finally, when it comes to communication within your family about wealth, here are a few points to consider:

- Accept that talking about family wealth is hard, but don’t wait for your parents or grandparents to bring it up. They may not know how to.

- Think about what you would like to learn and why. Try to make your questions as specific as possible. For example, “What are your expectations for how I will use any financial inheritance I may receive?” “What are your hopes for me regarding work and income, saving and spending?” “Do you expect me to join the family business or continue certain other traditions as part of my receiving this financial capital?”

- Think about who your parents or grandparents are, and how best to approach them. One-on-one? In the context of a family meeting? With a written note first to give them a chance to think?

Again, work, relationships, and communication are three areas in which we have seen members of the rising generation truly discover their strengths, weaknesses, and areas for growth. It is from such activities and self-reflection that something truly fundamental arises: clarity about your dreams. We have heard many parents tell us, “I don’t know what my children’s dreams are.” We have heard many members of the rising generation say, “I haven’t found my dreams!” Sometimes this emphasis on dreams can seem like a burden. One might feel like a failure if one’s dreams aren’t crystal clear. Our experience is that dreams become clear only with time, with effort, and as the result of a process of growth and exploration. They are almost never clear at the beginning of that process.

To offer you encouragement and inspiration in pursuing your dreams, here are lines from two poems, both of which speak to the journey of that great explorer Odysseus, himself a larger-than-life leader. The first comes from the Greek poet C.P. Cavafy’s poem Ithaca:

When you set off on the road to Ithaca

pray that the road be long,

full of adventures, full of knowledge.

Ithaca is the place we all want to get to, the object of our aspirations and hopes. Most people focus on the destination and want to get there already. But the rising is the journey.

The second comes from the Russian-born poet Joseph Brodsky’s poem Odysseus to Telemachus, which imagines Odysseus speaking to his son, Telemachus, who himself faced the challenge of rising in the shadow of such a great father:

Grow up, then, my Telemachus, grow strong …

Your dreams, my Telemachus, are blameless.

Your dreams, too, are blameless.

Rising in the Middle Passage

As we mentioned when we defined the term “rising,” it is not only young adults in their 20s and 30s who are rising. Every generation can rise. In the context of great financial wealth, we often see rising delayed until members are in the middle passage of life, in their 30s, 40s, or even 50s. Rising at this point includes everything we have discussed already, plus some special considerations.

One of those considerations, to return to Erikson’s stages of development, is that the challenge involves not only individuation but also facing the dilemma of stagnation versus generativity. Life can become routine. It can feel as though the past and regrets outweigh the future and hope. The antidote to such stagnation is generativity: a sense of giving back, distilling what you have learned and experienced, and using it for the benefit of others (your children, nieces and nephews, or other members of your community). Generativity is often key to the rising of family members in the middle passage.

To do so, it can help to seek the support and insights of others in your shoes. These may be other family members, such as siblings or cousins. They may be members of other families with significant wealth, who you can meet through membership organizations, philanthropic boards, or the like. The middle passage can be isolating for anyone, especially if surrounded by large financial capital. Use your networks to break down that isolation and practice active ownership that we discussed in Chapter 2. Taking active ownership may involve making your voice heard in the management of your financial capital and directing it to investments that suit your values. It may also involve taking a more active hand in bringing your larger family together to communicate, learn, and make decisions. Active ownership of your life may entail even larger steps, such as leaving a career or a relationship that feels stifling. Whatever the case may be, the middle passage is a time when it is crucial to ask whether you are leading your life or a life that you think others want for you.

Setting Off

Before closing this chapter, let’s return to the journey of rising generally.

With this journey in mind, here is a list of questions to reflect upon. If you have a coach or mentor, they are also great questions to get that individual’s reflections on, based on that person’s knowledge of you. If you are coaching a member of the rising generation, perhaps a child or niece or nephew, asking them to reflect on such questions can form the basis of meaningful conversations:

- Am I free or am I dependent?

- Have I found meaningful work?

- Am I a good friend?

- Can I feel compassion for myself?

- Can I express gratitude?

- Can I experience joy and humor?

- Have I taken part in larger civil society? In giving to others?

- In which areas do I want to grow further?

This list of questions can feel daunting. If it does, then take on a few at a time, perhaps covering the whole list over the course of six months or a year. The idea behind them is to be intentional about your rising.