Canada Is Larger than the U.S.

미국보다 캐나다가 더 넓어요

[Migukboda kaenadaga teo neolbeoyo.]

Special Adverbs

As we’ve discussed before, it’s often the little words in a language that are most important. Just think about how many times a day you use the words “the” and “a” in English conversation. Oops, and there’s another one too: “and”! That’s an essential one, isn’t it? Yes, it is, which is why we’re going to start out this chapter by covering this and similar words—known in English as conjunctions, or conjunctive adverbs.

Conjunctive adverbs

But what exactly are conjunctive adverbs? You know, it’s funny how sometimes native speakers don’t know much about the structure of their language. They just speak it! That’s one great thing about learning another language: you get to find out things about your own.

There are different kinds of conjunctive adverbs in English, but the simplest are little words like “and,” “but,” and “so” that connect two clauses or two complete sentences. For example, the conjunction “and” lets you turn this:

“I ate two pizzas for lunch. I’ll eat one more for dinner.”

into this:

“I ate two pizzas for lunch, and I’ll eat one more for dinner.”

Similarly, we have “but,” which combines these two:

“I usually eat two servings of spaghetti for breakfast. Today I only ate one.”

into a single sentence:

“I usually eat two servings of spaghetti for breakfast, but today I only ate one.”

And finally, “so” lets us take this:

“I only had ten candy bars today. Now I’m really hungry.”

and change it to this:

“I only had ten candy bars today, so now I’m really hungry.”

Hmm…these sentences are pretty strange, but for some reason I’m really hungry all of a sudden!

Anyway, my point is that in English these words can be inserted between two clauses or sentences to connect the ideas and form a new complete sentence. But in Korean it’s different. Now, I’m not saying Korean doesn’t have conjunctive adverbs—that would make for a pretty short chapter, wouldn’t it!? Actually, there do exist individual words for these conjunctions, but when you use them to connect two ideas, they’re expressed through…your favorite… conjugative endings.

Hey, come on, don’t roll your eyes! After all, you should be familiar with this idea, because we’ve already learned one example, the ending: ᅳ아서 / ᅳ어서 / ᅳ여서. And, as I’m sure you recall, this ending has two meanings: “and then” and “so/therefore.” Hmm…are you doubting that you’ve studied this before? I think you’re just in denial. Allow me to refresh your memory with the example sentences we used in chapters 16 and 20.

이 쪽으로 죽 가서 왼쪽으로 도세요. [I jjogeuro chuk kaseo oenjjogeuro toseyo.] Go straight this way and then turn left.

이 쪽으로 죽 가서 왼쪽으로 도세요. [I jjogeuro chuk kaseo oenjjogeuro toseyo.] Go straight this way and then turn left.

몸이 좋지 않아서 오늘 회사에 못 갔어요. [Momi chochi anaseo oneul hoesae mot kasseoyo.] I was sick so I couldn’t go to the office today.

몸이 좋지 않아서 오늘 회사에 못 갔어요. [Momi chochi anaseo oneul hoesae mot kasseoyo.] I was sick so I couldn’t go to the office today.

Okay, the conjunctive adverbs used here (“and then” and “so/therefore”) are expressed by conjugating the verb of the first clause with the ending ᅳ아서 / ᅳ어서 / ᅳ여서. Of course, it’s possible to divide each of these sentences into two clauses, in which case the adverbs would be rendered instead as full, independent words. This makes for a pretty simplistic way of speaking, but let’s check it out anyway.

For “and then,” you can say 그러고 나서, while “so/therefore” becomes 그래서, giving us:

이 쪽으로 죽 가세요. 그러고 나서 왼쪽으로 도세요. Go straight this way. And then turn left.

이 쪽으로 죽 가세요. 그러고 나서 왼쪽으로 도세요. Go straight this way. And then turn left.

몸이 좋지 않았어요. 그래서 오늘 회사에 못 갔어요. I was sick. So I couldn’t go to the office today.

몸이 좋지 않았어요. 그래서 오늘 회사에 못 갔어요. I was sick. So I couldn’t go to the office today.

Does that make sense? Obviously, it sounds smoother to use the conjugative ending, but either way works.

So let’s go on to look at two extremely common conjunctive adverbs: “and” and “but.” Conjugating verbs and adjectives to add these meanings is quite easy, because both endings follow pattern 1. The ending for “and” is -고, whereas the one for “but” is ᅳ지만. And then, the stand-alone conjunctions are 그리고 and 그렇지만, respectively. Here they are in context:

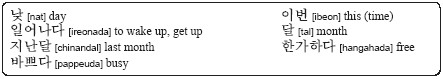

저는 낮에 자고, 밤에 일어나요. [Cheoneun naje chago, pame ireonayo.] I sleep during the day and wake up at night.

저는 낮에 자고, 밤에 일어나요. [Cheoneun naje chago, pame ireonayo.] I sleep during the day and wake up at night.

저는 낮에 자요. 그리고 밤에 일어나요. [Cheoneun naje chayo. Keurigo pame ireonayo.] I sleep during the day. And I wake up at night.

저는 낮에 자요. 그리고 밤에 일어나요. [Cheoneun naje chayo. Keurigo pame ireonayo.] I sleep during the day. And I wake up at night.

지난달은 바빴지만, 이번 달은 한가해요. [Chinandareun pappatjiman, ibeon tareun hangahaeyo.] I was busy last month, but I’m free this month.

지난달은 바빴지만, 이번 달은 한가해요. [Chinandareun pappatjiman, ibeon tareun hangahaeyo.] I was busy last month, but I’m free this month.

지난달은 바빴어요. 그렇지만 이번 달은 한가해요. [Chinandareun pappasseoyo. Keureochiman ibeon tareun hangahaeyo.] I was busy last month. But I’m free this month.

지난달은 바빴어요. 그렇지만 이번 달은 한가해요. [Chinandareun pappasseoyo. Keureochiman ibeon tareun hangahaeyo.] I was busy last month. But I’m free this month.

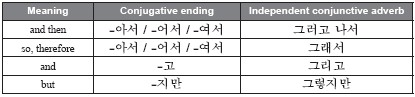

Let’s sum this all up with a handy table, shall we?

Maybe you’re wondering why all of the independent conjunctive adverb words begin with 그. This is because they’re all derived from the verb 그러다 (“to do so”), or the adjective 그렇다 (“like so”). So, literally, 그러고 나서 means “after doing so,” 그래서 means “because of doing so,” and 그렇지만 means “despite doing so.” Interesting, huh?

Frequency adverbs

There are tons of adverbs in Korean, just like there are in English. But I’m a nice guy, right? So of course I’m not going to introduce all of them in this book. Instead, we’re just looking at some of the most special. Keeping that in mind, let me usher in the second type: frequency adverbs.

Frequency adverbs are used to describe how often (or, um, frequently ^;^) an action takes place. Can you think of some examples of these? Sure you can! There’s “usually,” “sometimes,” “(not) at all,” “often,” “always”… And then, can you arrange them in order from the lowest to the highest frequency? I believe you can. Using this order, I’ll create some examples for you:

저는 이번 주에 전혀 씻지 않았어요. [Cheoneun ibeon chue cheonhyeo ssitji anasseoyo.] I didn’t wash myself this week at all.

저는 이번 주에 전혀 씻지 않았어요. [Cheoneun ibeon chue cheonhyeo ssitji anasseoyo.] I didn’t wash myself this week at all.

저 는 가끔 샤워 를 해 요. [Cheoneun kakkeum shyaweoreul haeyo.] I sometimes take a shower.

저 는 가끔 샤워 를 해 요. [Cheoneun kakkeum shyaweoreul haeyo.] I sometimes take a shower.

저는 보통 손을 안 씻고 밥을 먹어요. [Cheoneun potong soneul an ssitgo pabeul meogeoyo.] I usually eat without washing my hands.

저는 보통 손을 안 씻고 밥을 먹어요. [Cheoneun potong soneul an ssitgo pabeul meogeoyo.] I usually eat without washing my hands.

저는 이 닦는 일을 자주 잊어요. [Cheoneun i tangneun ireul chaju ijeoyo.] I often forget to brush my teeth.

저는 이 닦는 일을 자주 잊어요. [Cheoneun i tangneun ireul chaju ijeoyo.] I often forget to brush my teeth.

저는 머리에서 항상 냄새가 나요. [Cheoneun meorieseo hangsang naemsaega nayo.] My hair always smells.

저는 머리에서 항상 냄새가 나요. [Cheoneun meorieseo hangsang naemsaega nayo.] My hair always smells.

Stop! Please stop this! Oh, why? Please improve your hygiene, if not for your own health, then for mine! Phew. Sorry, I’m a little finicky when it comes to cleanliness. Anyway, you get the idea of frequency adverbs, right? Rather than belaboring the point, let’s move on to another important category: comparatives and superlatives.

More, Most

When I was little, I’d often hear this question: “Who do you like more, your mommy or your daddy?” This isn’t a very common question in the Western world, but in Korea children are asked this a lot. I always thought it was silly, because it was so easy to answer: “Whoever pays my allowance!” ᄏᄏ.

I doubt you’ll get asked this question in Korea, but there are others that follow the same principle. For example, maybe you’ll hear this:

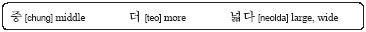

미국하고 캐나다 중에 어디가 더 넓어요 [Migukago kaenada chunge eodiga teo neolbeoyo?]

미국하고 캐나다 중에 어디가 더 넓어요 [Migukago kaenada chunge eodiga teo neolbeoyo?]

Between the U.S. and Canada, which is larger?

Hmm…let me see. Actually, I don’t know the answer to this one. But frankly, it’s not really that important to me. I’m a lot more interested in which is larger, my house or my neighbor’s. ^^ So instead of paying attention to the particular meaning of the question, let’s focus on the adverb 더, which has the meaning of “more.” In English, it can be quite confusing to know whether to make a comparative by saying “more” or adding the comparative suffix “-er” to the end of the word. I mean, think about “fun.” Is it “more fun,” or “funner,” I still don’t know! In Korean, though, you don’t have to worry about that. Just add 더 before any adjective…it even works for verbs, too!

And what about the element 중에 in the sentence? When two choices are being discussed, you put the word 중에 after them to mean “between” or “among.” (중 means “middle,” but its meaning changes with the particle -에.)

Okay…I’ve had a little time for some research, so I’ll ask again: which one is larger? No idea? Here’s the answer:

미국보다 캐나다가 더 넓어요. [Migukboda kaenadaga teo neolbeoyo.] Canada is larger than the U.S.

미국보다 캐나다가 더 넓어요. [Migukboda kaenadaga teo neolbeoyo.] Canada is larger than the U.S.

Interesting, huh? It’s tempting to say that the U.S. is bigger, but actually it’s Canada that has more land area by just a bit. But what’s that particle stuck on the end of the first noun? What could that mean? That’s right, it’s the equivalent of “than”! The particle -보다 goes on the end of the first object being compared, the one that corresponds to the “less” portion of the comparison. And then the word 더 goes directly before the verb or adjective. So remember, … 보다 …더. Got it?

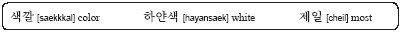

So now you know “more,” but what about “most”—the superlative? Just as before, you never have to worry about whether you need to include the separate word “most” or tack on “-est” to the end of the word. In Korean, all you need to do is put 제일 before the verb or adjective. So we can say:

어떤 색깔을 제일 좋아하세요 [Eotteon saekkkareul cheil choahaseyo?] What color do you like most?

어떤 색깔을 제일 좋아하세요 [Eotteon saekkkareul cheil choahaseyo?] What color do you like most?

저는 하얀색을 제일 좋아해요. [Cheoneun hayansaegeul cheil choahaeyo] I like white most.

저는 하얀색을 제일 좋아해요. [Cheoneun hayansaegeul cheil choahaeyo] I like white most.

Just like 더 is the equivalent of the comparative“more” in English, 게 일 is the superlative“most.” See how that works? Easy!

Well, we’ve spent a lot of time together now…22 chapters’ worth, right!? And I can honestly say that I like you more than any other language study partner. I’m having the most fun guiding you through the world of Korean!

Korean Style: He’s an owl.

An owl!? Is there a legend of some sort of owl man in Korea, like the American Batman or Spiderman? Well, anything’s possible. There certainly could be a man who was bitten by a strange owl and was given super powers. But not in this case!

If someone says 그 사람 정말로 올빼미예요, they’re saying that the person doesn’t sleep at night, but during the day instead.

몰빼미 means “owl,” and of course you know owls are nocturnal. There’s a similar expression in English, isn’t there? You can describe someone as a “night owl.” But it doesn’t stop there, because Koreans frequently use lots of other animal comparisons to describe people. Check out the list:

그 사람 정말로 몰빼미예요. [Keu saram cheongmalro olppaemiyeyo.] He/she’s a real owl. (He/she is awake at night and asleep during the day.)

그 여자는 여우예요. [Keu yeojaneun yeouyeyo.] She’s a fox. (She’s sly.) (Careful—this doesn’t refer to looks like it does in English!)

남자들은 다 늑대예요. [Namjadeureun ta neukdaeyeyo.] All men are wolves. (Men are no good.)

제 남편은 곰이에요. [Che nampyeoneun komieyo.] My husband is a bear. (My husband is slow-moving.) or, (My husband is insensitive.)

그렇게 많이 먹으면 돼지가 될 거예요.

[Keureoke mani meogeumyeon twaejiga toel keoyeyo.] If you eat so much, you’ll become a pig. (If you eat so much, you’ll get fat.) (Be careful! This can be quite offensive.)

그 사람은 물 서는 완전히 물개예요.

[Keu sarameun mul aneseoneun wanjeonhi mulgaeyeyo.]

He/she is a perfect seal in water. (He/she swims very well.)

Which animal are you?