Mother insists

we must visit Poland

one more time

before we sail to America.

And by we she means

herself, me, and Ruth,

but not Father,

who must stay home and work,

and by work

I think by now

you know what I mean:

It’s all about getting those American visas.

Father says no.

It’s too dangerous to go to Poland.

Perhaps they won’t

let us back into Germany,

perhaps they will snatch us

off the train,

put us in a concentration camp.

Mother doesn’t care about perhaps.

She cares about Pabianice,

the little city where her parents live,

and Father’s mother,

and uncles and aunts and cousins.

She cares about not seeing them

ever again

once we go to America,

an ocean away,

for who can imagine traveling that far

more than once,

even after this Nazi craziness is over.

Father says no.

But Mother insists,

and that is that.

We travel by train,

on a trip we have taken before—

every summer we go to Poland,

every summer we stay

with my Kleinert grandparents,

Marcus and Salka,

and also with Grandma Salzberg.

My grandma Salzberg

lives in a simple house,

without even an indoor toilet,

but she makes Friday night Shabbos

like none other,

with chicken soup and fish and challah

and warmth.

I can walk from Grandma Salzberg

to my Kleinert grandparents,

an easy and shady walk,

pleasant except for the part

where I pass the chicken market.

The chickens wait

for the housewives to choose them.

A chicken that is chosen

gets killed, of course,

and goes to the chicken flicker,

who plucks its feathers

and singes off the ones he can’t pluck.

I hold my breath against the nasty burning smell

of the singeing that greets and follows me

on my walk.

And from this comes delicious soup!

My grandpa Marcus,

the dentist,

lets me sit in his laboratory

and see what it is like

to make people new teeth.

He talks about science,

such as the importance of good hygiene

and how we must always wash

the fruit we buy at the market

so we don’t get sick from germs.

At both houses,

the feather beds are like

sleeping on clouds,

and everywhere there is family.

There is my aunt Flora,

who is Mother’s sister

(and who is a dentist like Grandpa Marcus),

and my cousin Rita,

who is Aunt Flora’s daughter,

and Uncle Ludwig,

who is Aunt Flora’s husband,

(but who is not Rita’s father,

as he is Aunt Flora’s second husband),

and there is Aunt Henia,

who is Father’s sister

(and whose husband died,

so she lives with Grandma Salzberg),

and cousin Manja,

who is Aunt Henia’s daughter.

We have taken this trip many times before,

but never like this,

never with German police searching us—

our bags and our bodies—

on the train.

And we have stayed with our family before,

but never for (maybe) the last time,

which makes things different.

Hugs last longer.

Talk among the grown-ups

is more serious,

and yet some things are the same.…

Uncle Ludwig is still the best uncle

(not counting Uncle Max, now in America).

He takes me to his silk factory

and writes his name for me

in the shape of a swan.

Aunt Henia is still the funniest aunt,

who makes me laugh and laugh.

My cousin Rita still likes to walk

all over me when we are sharing the bed

at my Kleinert grandparents’ house;

and cousin Manja is still

sweet Manja.

On the train back to Hamburg,

I am tired, and sad,

but also happy,

because visiting Pabianice always makes me happy.

Then we are in the station in Hamburg,

and there is Father,

and he is happy,

because no one snatched us off the train,

no one put us in a concentration camp.

We are together again.

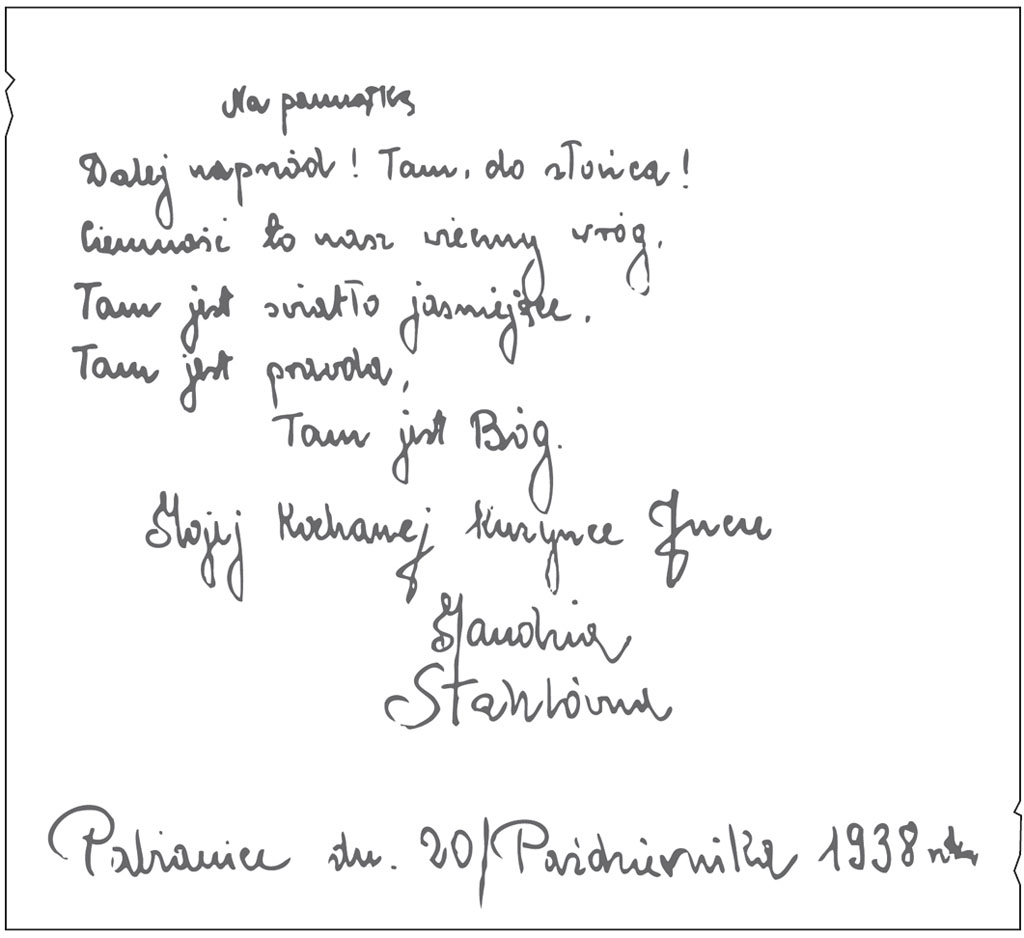

Forward! Over there, to the sun.

Darkness is our eternal enemy,

Over there is bright light.

Over there is truth.

Over there is God.

To my beloved cousin Jutta,

Manja Stahl

Pabianice, October 20, 1938

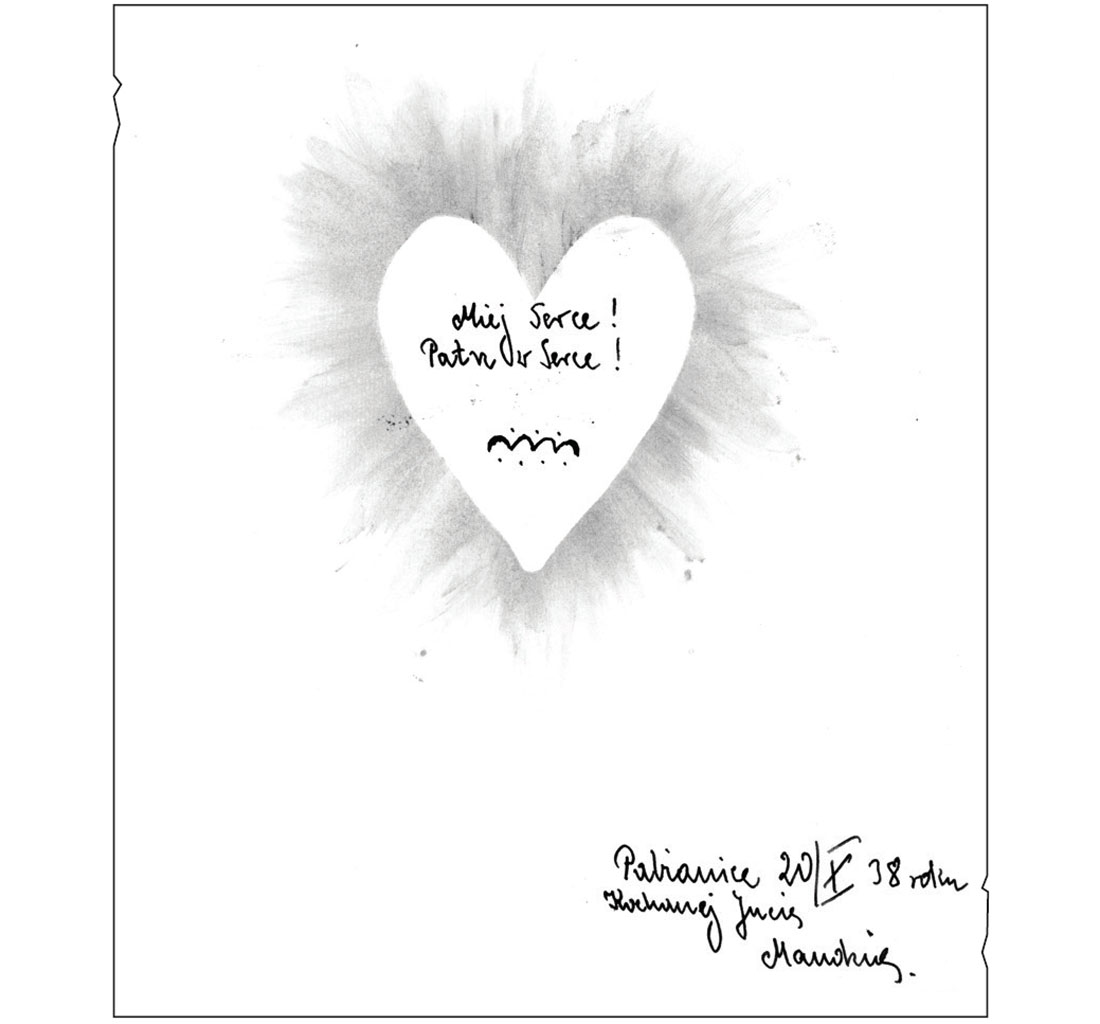

Have a heart!

Look into a heart!

Pabianice,

October 20, 1938

Manja