Themes Part II

Monuments and museums

Archeological sites call for many of the same camera techniques as regular buildings, but there are some other things to consider. Some of the more remote, or extensive, sites offer possibilities for very evocative photography. The ruins of Chichen Itza, shown here, are perfect examples of this kind of monument. On a smaller scale, there are similarly atmospheric sites everywhere in the world; only the most accessible and famous, such as Stonehenge, the Pyramids, and the Parthenon, are under so much pressure from tourism that photography is restricted.

Nevertheless, access is usually the first consideration if you are planning to photograph an archeological site. There are nearly always some kinds of restriction placed on entry to protect delicate monuments. Check these carefully before going, as well as opening and closing times, if any. You may want to shoot at sunrise or sunset, but not all monuments are open to the public at these times. In addition, check to find out if there are extra fees for photography—this varies from place to place, but in general you are more likely to be charged if you appear to be a professional photographer; also tripods may be banned. Light-sensitive artifacts, such as polychrome murals, may be off-limits for photography.

Chichen Itza

The statue of Chacmool, an Aztec god, in its typical but unusual posture. Statues are now rarely found in situ because of the danger of theft, making situations like this valuable for archeological photography.

Ancient monuments more than most other buildings benefit from not having people in view, but with a large monument this is rare. The best opportunities are nearly always as soon as the site opens. Otherwise it is usually a matter of waiting for moments when other visitors are out of sight. For atmospheric shots, treat the site as you would a landscape, and try to plan the photography for interesting light—at the ends of the day, or possibly with storm clouds. Also look for wide-angle views that take in close details such as a fragment of sculpture, as well as the distance. In addition to these basic scenic shots, consider the more documentary shots, such as a record of a bas-relief and other carvings. Here again, the lighting is important: raking light across the surface is usually the clearest for carvings in low relief.

Musée Guimet

A stone Khmer statue at the museum in Paris founded with this large collection from Cambodia.

Most museums do not allow casual photography. The procedures for shooting involve written permission, increasingly difficult to obtain, payment (often high), and restriction of use. As museums normally own the copyright in the works they exhibit, there is no way around this. The answer, if it qualifies as such, is just to try, but be prepared to give up when stopped. Open-air museums tend to be rather more relaxed.

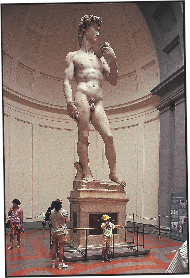

David

Sometimes, stepping back from a close view of an art object in display is worth it to show the setting and people. Michelangelo’s statue David is lit by daylight at the Accademia in Florence, Italy.

Landscapes and viewpoint

At some point on every trip to a fresh area of landscape, the need sets in to find the defining shot—the single scenic image that captures the sense of place. Landscape photographers do this all the time, and don’t usually limit themselves to one view that encapsulates everything. It depends on interpretation as well as opportunity, and may take a day or two of traveling around before you have an idea of what makes the scenery distinctive. Sandstone mesas and buttes punctuating the great arid distances of northern Arizona, the bocage landscape of northern France that is dense with hedgerows, the succession of alps and hillsides in parts of Switzerland—these and countless others are the themes of specific landscapes.

Emptiness

Rather than search for occasional strong features like an outcrop, I wanted here to convey the sense of emptiness in the northern Sudan desert. My only concession was a small shrub to emphasize the sense of loneliness.

Catching glimpses and building up a composite view as you travel is one thing; translating this into one image is quite another. One of the odd things that happen while traveling through any landscape, whether by car, boat, or train, is that the eye and mind “see” a view that is in fact made up of many fleeting impressions. It’s more akin to watching a movie, and when it stops—when the vehicle stops—the clear view of the scene usually resolves itself into a mess. Foreground obstructions in particular, suddenly appear, and often there is a frustrating lack of what the photographer has formed in his or her mind as the perfect view.

Horsehoe

A well-known view of the Colorado River near Page, Arizona, aptly named Horseshoe Bend. There is, in fact, little choice of viewpoint here, and it more or less dictates a very wide-angle lens.

And here lies the problem—but also the solution. Expecting a certain kind of image without obstruction courts disappointment, even while it can also spur you on to making more effort. Lookovers are not the only camera positions, but they are the easiest to visualize. Viewpoint certainly makes or breaks a scenic shot, but it is often more rewarding to think through the essence of the landscape. If a forest is too dense to allow an overall view, try to work with the denseness. Deserts, steppes, and plains are often unremittingly flat, but rather than look for a way out of this by finding an elevated viewpoint, why not stress the plain, simple horizontality with a dead-on, minimalist image?

Balinese ricefield

Clear light and an intense blue sky made this a shot to be sought after—with young rice just being planted, the water in the paddies would reflect the color of the sky. It took some time to find a clear overview from a little higher up the hill.

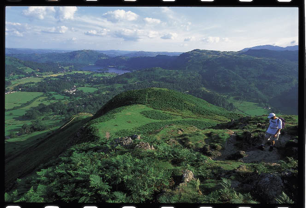

Lake District: This part of England’s Lake District, near the town of Grasmere, is known for its rolling green hills, and these needed a moderate elevation to show them off.

Keralan palms

In the local language, the name for the south Indian state of Kerala means “coconut palm,” which abound. An overview from a distance would be less typical and less effective than the view from a small boat crossing one of the many small canals in the backwaters.

Landscapes and light

If viewpoint is one key ingredient in capturing a successful landscape photograph, the other is certainly light. The quality of light varies endlessly with time of day, season, and weather. This is really all about timing, and having found the camera position that gives the essential view, you then need—or at least hope for—some special kind of daylight that will elevate the image from the documentary to the evocative. This, at any rate, is what most of us feel, even though the odds are, by definition, against us.

Rivermouth

Deciding when to shoot is critical if you want to give yourself the best opportunity to capture your subject in complimentary lighting; here the dusk light sets off this Malaysian scene beautifully.

Above all, traveling ensures that you will never have enough time in any one place, for whatever kind of photograph. As photographers we are conditioned to want a certain specialness from a picture—something that sets it apart from others that have been taken before—and in shooting landscapes this usually comes down to the lighting. As two pairs of photographs here amply demonstrate, in the right circumstance a shaft of sunlight can transform an image. There is just so much planning that you can usefully make, particularly when traveling on a schedule; weather report, time of day, and angle of the sun on key features. After that, it’s a matter of how much time you are prepared to spend waiting for one shot, the odds of the light changing significantly in that time, and luck. The Spider Rock shot on the following page was definitely luck; the stormy sky held no good promise, and with no more than 15 minutes left before sunset, the view from this overlook would have been wasted if the sun had not broken through for less than two minutes. I was preparing to write off the afternoon’s photography before this happened, but felt a duty to see it through, just in case.

Beyond all this is the matter of taste. The examples of lighting here are unashamedly picturesque, and you might prefer a more understated light. Choosing a certain viewpoint and composing the shot in a particular way means taking into account the distribution of light across the scene. Flat lighting, for example, is likely to suggest quite a different composition for one scenic location than would bright raking sunlight.

Passing clouds

The shot, of the Yorkshire market town of Richmond, was pre-determined as the job called for the first glimpse of it on a walk across England. The only variable was therefore the lighting, on a difficult day with strong winds and inconvenient clouds. The difference that a brief shaft of sun made is obvious.

Misty tree

Even allowing for differences in taste, there is little doubt that this striking tree silhouette is best served by lighting that helps it to stand out from its surroundings.

Country life

Despite the high visibility and impact of cities, most of the people on the planet still lead rural lives. For the traveler this may not be immediately obvious. Most journeys to other countries begin in a major city, often the capital, because it’s nearest the arrival airport. Cities are, in any case, the hubs for traveling outward, and the easiest place to arrange itineraries, buy provisions, rent cars, and organize travel documents. Nevertheless, in terms of normal life and the average human landscape, the countryside dominates. On the surface, a pattern of rice fields glistening on a lush Southeast Asian hillside may seem exotically different from the flat wheat plains dotted with grain elevators in the Midwest, but the concerns of the people who live there are essentially the same.

Life revolves around the seasons and the agricultural cycle. The busy times are planting and harvest; the communities are usually small; the weather determines the prosperity from one year to the next.

English village

A classic of its type, at least in terms of what people expect to see, is this view of a stone-built village in the Lake District of northern England. The viewpoint is down a steep approach road.

As you travel, keep this underlying continuity in mind. The specific activities you come across may be novel—repairing dry-stone walls on a Yorkshire moor, or bringing in baskets of harvested rice to a communal depot in upper Burma—and the dress and appearance of the people may add character to the pictures, but the general purpose of life is pretty much the same. Knowing this, it helps in planning your shooting to find out what crops are grown, what animals raised, and so what activities are happening at this particular season. After the harvest is in, country communities the world over have time to spare—and this is not only when things get repaired and painted, but also when festivals—even marriages—are most likely. Rural communities tend to be more conservative than those in cities, and customs more likely to be preserved.

Country life is also more distinctively regional than that of cities, where buildings, shops, and even the products for sale reflect globalization. The land and its potential can sometimes change sharply in several miles. With a sharp eye you can highlight these practical differences in your images.

Southern India

A south Indian duck farmer shoos his charges across a small canal in the Keralan backwaters in the early morning.

Dry-stone wall

A traditional technique in parts of the north of England, is the building of field walls without mortar, relying instead on carefully chosen stones.

Burmese rice market

Burmese women carrying sacks of rice from their own farms to the communal mill for weighing.

Forests

There are several kinds of forest and woodland, and the three most common of these are temperate deciduous, coniferous, and rainforest. Although many are under threat from logging and burning, they are still rich environments for nature photography (except for coniferous plantations).

Light levels tend to be low, particularly in rainforests, where the upper canopy of leaves effectively cuts off the ground from all light, and northern coniferous forests. Light levels may be too low for handheld photography and reasonable depth of field—as much as 12 ƒ-stops less than the sunlight above. A tripod is always useful in these conditions. One benefit of deep forest gloom is that all the light is diffused and so contrast is low, and this helps to simplify the tangle of vegetation. At the same time, this diffusion can give a green cast to the image—this may even benefit the image, but remember that you can color-correct with the white point balance, or later on the computer.

Temperate rainforest

Rainforest also exists, though rarely, in cooler climates, and one of the most extensive is the Hoh rainforest in Washington State on the northwestern coast. A clearing helps to open up the normally restricted view.

In less dense forests, and at the edges and along riverbanks, some sunlight penetrates. This tends to give a dappled effect, which might cause contrast problems. Look for subjects (flowers or animals) that are lit by patches of sunlight and expose for these. In fact, as a general rule, the woodland edges and glades have a greater variety of animal life. Large mammals are not common, but this lack is more than compensated for by the many different small habitats, with abundant plants, insects, and fungi. Close-up photography is particularly rewarding in woodland, but this in particular usually calls for a tripod.

Aspens in fall

Aspens turning yellow on a hillside in Colorado. The angle of the sunlight, coinciding with that of the slope, makes the most of the intensity of color.

Tropical rainforest

An aerial view of rapids and islands on the Upper Mazaruni River in Guyana. With dense tropical rainforest, an aerial perspective is often the only way to get a sense of the habitat in a single image

Tripod for low light

Forests generally have low light levels, and for static subjects such as plants, a tripod is essential. It helps if the design allows the angle of the legs to be adjusted.

In the detail

Closing in on the details of a scene has a number of advantages in photography. One is that it offers a refreshing change of scale to the images. Another is that it encourages graphic experiment—such as in composition, cropping, and the juxtaposition of colors. And more than this, close-ups play a key role in interpreting content—isolating a detail to focus attention. While these are universal to all kinds of shooting, travel photography stands to benefit more strongly than most. A trip of a week or two will probably result in a large number of images, and a proportion of close-ups will add a valuable change of graphic pace. Photographs of people and landscapes tend to conform to a relatively small range of compositions. There is nothing wrong with this, but close-up shooting allows a striking freedom of imagery, even to the point of offering a visual puzzle to the audience. Detail works in travel photography because it allows the observant eye to pick out the differences in material culture and in nature. For example, the way in which the sheaves of rice have been bundled, tied, and stacked by a Balinese roadside tells much about the islanders’ way of life and their own attention to detail even in the most mundane of tasks. And the celebration of diversity is, after all, the underpinning of travel photography.

Laotian temple

Glass mosaic set into the wall of a Buddhist chapel at the temple of Wat Xien Thong, Laos, Luang Phrabang, has a naïve charm.

Balinese rice

Sheaves of freshly cut rice neatly tied and stacked by the roadside in Bali, awaiting collection.

Kyoto doorway

A Japanese tradition is the noren curtain, hung in front of restaurants, shops, and teahouses. The contemporary designs, featuring symbols or calligraphy, are usually of a very high standard.

Ginseng shop

Shop signs are always worth looking for, particularly when they offer something out of the ordinary—here ginseng in an old-fashioned Chinese shop in Malacca.

The ordinary

Lou Klein, the Art Director at Time-Life whom I quoted at the very beginning, began one briefing for a book I was about to do on a European city by saying “I want to see what the milk bottles look like.” He was not being literal (although I did bring back a photograph of a bottle on a doorstep just in case). It was by way of encouraging me to shoot the ordinary, everyday things in another culture, to give an accumulated picture of daily life. By doing this it should be possible to convey something of the experience of being a part of another community—also its similarities to and differences from our own. Photographs of ordinary life and its details are potentially absorbing to anyone from another culture, because they can, at the same time, relate clearly to everyday reality anywhere, yet also highlight a way of doing things that has evolved separately.

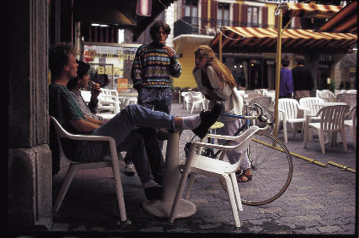

Street life

A group of friends outside a café in a small French Provençal town.

This is all about people going about doing unexceptional things just as you would on an unremarkable day—but in an unfamiliar environment. Just as the exotic can be made familiar through photography, so the ordinary can be made into something that calls for attention.

Balinese offerings

An island of Hindu tradition in a largely Muslim Indonesia, Bali continues to follow a largely rural way of life, despite the tourist industry. Offerings and ceremonies are the norm rather than the exception.

Brussels café

Cirio is one of Brussels’ traditional café-restaurants; little changed in a century, with a regular clientele. Early weekday mornings are always quiet.

A game of boules

On the waterfront at Cassis, a small French port near Marseilles, locals pass an afternoon playing the traditional game of boules.

The unexpected

One of the paradoxes of travel is that it can always be relied on to deliver the unexpected. This sounds contradictory, but on the basis of experience it’s true. Of course, the odds of coming across the undeniably strange corners of life are distinctly improved by traveling to, or at least wandering about in, the less obvious tourist destinations—and by doing this frequently. As far as most photographic opportunities on the road are concerned, time spent at a destination is subject to the law of diminishing creative returns. The excitement of a first sunset, then sunrise, at a Grand Canyon overlook is slightly diminished on the following day, and it doesn’t take long before you exhaust the obvious. But the unpredictable, slightly weird moments that stop you in your tracks behave differently. They keep on coming the more that you travel, albeit at a much lesser frequency than the staple of scenic views, markets, and monuments. Naturally, only you are the arbiter of what counts as odd and quirky on your travels. Personally, I count the odder moments among the most satisfying from a trip.

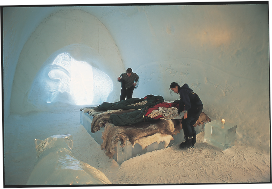

Ice hotel

A considered commercial enterprise certainly, but it is still remarkable that anyone would pay five-star prices to sleep on a block of ice in a hotel that melts every summer—the Ice Hotel in northern Sweden.

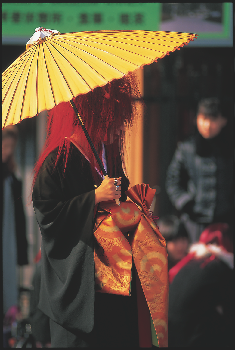

Japanese gothic

Since the 1960s, Harajuku in Tokyo has been a center during weekends for the weirdest in youth fashion. It goes through changes year by year, with this odd mixture of Geisha and Goth current.

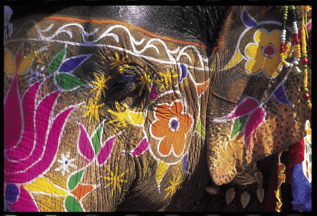

Customized paint job

For the Indian festival of Holi, the elephants of Jaipur, who live with their owners in the southeast quarter of the city, receive an elaborately designed coat of paint.

A helping hand

This enterprising coconut plantation owner in southern Thailand saved himself labor expenses by training local macaques to do the work of climbing the palms to collect the coconuts, and then help load them.

Reworking clichés

A standard mantra of travel photography is “avoid cliché,” as in “don’t waste your time taking another shot of the Eiffel Tower like everyone else/or of Mount Fuji with a bullet train racing by in front.” Well, yes and no. Images become clichés in a two-step process—first, the view is good, second many people take it. The word cliché comes from the French term for a photographic negative, from which identical prints can be churned out, so it’s fitting that photography in particular suffers from this.

However, the problem is often that there are natural viewpoints for many scenes that just happen to work very well, if not, most photographers would choose them without prior knowledge. There is one famous view of San Francisco from a grassy hill that takes in a row of Victorian gingerbread houses in the middle distance, with downtown beyond. It works, undeniably, and has been used endlessly. Interestingly, there is just one small viewpoint from which you can see everything clearly and neatly arranged, and there is no missing the spot—the grass has been worn away by the feet of countless photographers.

There are many other examples, such as Angkor Wat from the other side of the northwest pond (the only spot that gives a reflection). The disappointment is simply that someone else got there first. As new destinations come onto the travel circuit, views that are fresh because rarely seen quickly become stale through repetition.

When faced with a popular subject, such as the Taj Mahal or Machu Picchu, the first question to ask is whether you are deliberately looking for a less-good viewpoint for the sake of being different. If you want eventually to sell the image as stock photography, that might not be sensible. It might be better to keep the viewpoint and work some other variation, such as unusual lighting, or having someone or something different in the foreground. Indeed, foregrounds can be the savior of many views, because they make it possible to ring some changes by moving a little and perhaps by using a different focal length. The examples here are mini case histories—my on-the-spot solutions to very over-photographed locations. It is pointless to list the different compositional techniques and types of viewpoint, because such formulas are themselves clichéd. The only meaningful solution is to take time, explore, and be imaginative. And realize that any successful photographic treatment of a subject has the potential to become a cliché, simply by becoming popular.

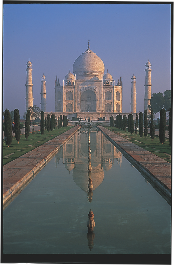

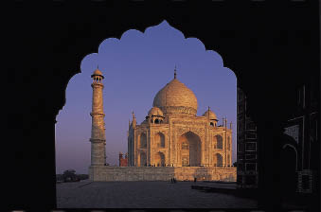

Taj Maha

So heavily photographed is the Taj Mahal in Agra, India, that you might despair of finding a fresh view. Indeed, there really is no angle that has not been used before, but the head-on symmetrical shot down the length of the reflecting pools is certainly the cliché. More interesting graphically is the view from one side and farther back, through an arch. Not surprisingly, however, of these two images it is the cliché that sells best as stock photography.

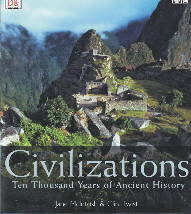

Machu Picchu

This ancient Inca site in the Peruvian Andes is another location with one obvious viewpoint, endlessly reproduced. It does, admittedly strike any first-time visitor as impressive, and there is no point in not trying your own version. Nevertheless, I also wanted a slightly more original view, and found it on the path down from the first position. Fortunately, one publisher also wanted a different view for a book jacket; this was the one chosen.