Appreciating Light Part I

The quality of light brings so much to the character of a photograph, and much will depend on the location, the time of year, and the time of day. If your travels have taken you to a previously unvisited destination, and an “exotic” one at that, in all likelihood you will find the quality of light and the way it behaves during the course of a day very different from your experiences at home. While this may take a couple of days to adjust to, you’ll soon be appreciating the opportunities it affords you.

Exactly sunrise

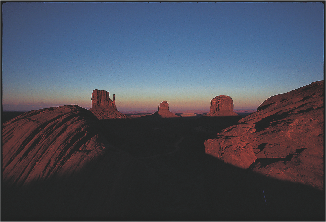

Sunrise photography depends on clear air for the full red effect, but the moment lasts just a few minutes. Sunrise is often most effective when used for a silhouette, as with the rock formations known as The Mittens in Monument Valley.

For general outdoor shooting, probably the most favored natural light for photographers is moderately low sunlight, as at midmorning and midafternoon. This is the lighting that dominates, for instance, travel brochures. Variations and extensions of this are when the sun is quite close to the horizon, although here the shooting window is much shorter, which means fewer images. The reason for the commercial popularity of bright-sun-but-not-too-high light is that this is tourist weather—the conditions in which most people like to travel for pleasure.

Some photographers, however, think that you can have too much of a good, or at least a predictable, thing. Certainly, given the constant demands of publishing and advertising to come up with striking, different new images, travel photographers are under pressure to find different light treatments. The aesthetics of “nice lighting” are, after all, quite fashionable. And fashions change.

In this section, we’ll look in detail not only at how light behaves and the effect it will have on your photographs during the course of a day—from sunrise to sunset—but also how this behavior and resulting impact on photography is governed by where your are in the world. In addition, it’s also important to understand of the significance of the direction of light in relation to the subject—whether the subject is lit from behind, from the side, or from the front—as this will drastically alter the quality of the image.

Climate and light

Natural light depends on weather, which depends in turn on the climate. Traveling makes you more conscious of this, partly because you are likely to be more exposed to outdoor conditions than usual, and partly because you are likely to be in a less familiar climate (this depends, of course, on how far you have traveled). World travel is now so much easier, cheaper, and more common than it was, say, twenty years ago, that more and more of us are experiencing very different climates on our trips. There are a dozen major climatic zones (including mountains as one) according to the standard classification, but of course there are rarely sharp divides between them. Microclimates also add variety.

Although I’m stressing the effect that climates have on light, there is also sometimes the more practical matter of accessibility. Climates that have extreme seasons may also make it difficult to get around, particularly in less–developed places. The wet season in a monsoonal country like Cambodia, for example, turns most of the roads to mud, and this drastically restricts the areas of the country you can visit. The summer in the Sudan brings the possibility of the haboob, a huge, sudden duststorm that can travel at speeds of 50 mph (80 km/h) with a front wall of up to 3,000 ft (900 m). These kinds of climatic detail call for very specific research; use the climate maps and descriptions that follow as an introduction and general guide, but for your exact destination do some in-depth research. Finally, there’s the issue of comfort. Shooting outdoors at 104˚F (40˚C) is no joke, and will slow most people down. Very low temperatures also take up time and energy—removing gloves, unzipping jackets, avoiding frostbite, and so on. Remember to factor this in.

Tropical light

Tropical wet

Monotonous and sultry, with no seasons and little variation in the heat and rainfall, both of which are high. Never cool, and while average temperatures are around 80˚F (26˚C), it feels hotter and more enervating because of the high humidity. Most of the rainfall is convectional, typically late in the afternoon as thunderstorms, with squalls. Often cloudy, but mornings start off bright.

Examples: The Amazon, Borneo, New Guinea.

Lighting issues: Sun intense when it appears. Probability of sunrises, and sunsets if there has been a late-afternoon thunderstorm to clear the air. Midday sun overhead and difficult for shooting. Rains heavy, but usually brief. Spectacular cloud formations from convectional rain.

Equipment issues: High heat and humidity are potentially damaging. Heavy rains demand very good protection.

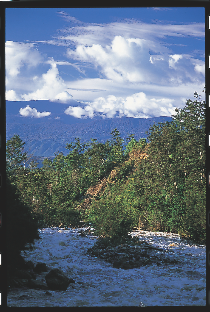

Irian Jaya

An equatorial climate is not all rain, even if hot and sticky. Early and late, as here in the Baliem Valley, the light can be rich and the cloud formations often piled high.

Surinam

A village ceremony in the interior of this South American country, typically overcast but much brighter than equivalent weather in a temperate climate.

Borneo

Midday sun on the equator is harsh, and in shaded locations like this, the contrast is so high that shadow details are inevitably lost.

Tropical monsoon

A variation on Tropical wet in that rainfall is concentrated in one definite season—the monsoon—which often breaks on one particular day. There are commonly three seasons: rainy (during which there are still some drier, sunny periods), followed by cool dry, which gradually changes into hot dry.

Examples: Indo-China, most of India.

Lighting issues: Seasonality makes the timing of a trip critical. The best sunshine is immediately following the monsoon, but skies can be unremittingly blue and therefore ultimately boring. The dry period before the monsoon can be hazy. How heavy and continuous the monsoon rains are depends on the region.

Equipment issues: For the rainy season, see opposite (Tropical wet). The end of the dry season can be very hot.

Thailand

The more familiar light is the clear, often cloudless skies of the dry monsoon in the cool season—crisp in the early morning and late afternoon, but with a certain monotony of blue sky.

Early morning

Shooting at the start of the day, when early-morning mist clings to the ground can add atmosphere to your photographs.

Light in dry climates

Savannah

Another tropical climate, with less overall rainfall than the previous two, and a long, distinctly dry season. These conditions result in large areas of grassland instead of forest. A rainy season is followed by a cool dry season, becoming hot dry.

Examples: East Africa, the Guiana Highlands.

Lighting issues: Dry season is light, bright, and clear, with particularly good visibility in upland areas like East Africa. Rainy season offers variable light, not as heavily overcast as in Tropical monsoon regions.

Equipment issues: Dust is the main problem in the dry season.

Guiana Highlands

The high savannah of southern Venezuela in May, which is the start of the hot season (although the height of the base plateau at around 4,900 ft (1,500 m) keeps the temperatures bearable). Generally clear skies, and dry.

South Africa

Rhino capture in the Pilanesberg National Park, near Sun City, South Africa. May in the southern hemisphere is winter, and at over 3,300 ft (1,000 m) this plateau area is crisp, cool, and dry. High UV-content gives shadows and distances a bluish cast.

Semi-arid steppe

A dry climate with low, irregular, and undependable rainfall. Drought years are interspersed with years of moderate rain, but are hard to predict. In the tropics, summer is hot and winter cool, but further north, as in the Asian steppes, the temperature range is greater, with hot summers and cold winters. Rainfall distribution by month varies from region to region, but is always unreliable.

Examples: Afghanistan, northern New Mexico.

Lighting issues: High percentage of clear skies, and in the driest season often no cloud for days at a time, giving solid blue skies.

Equipment issues: Needs protection against dust.

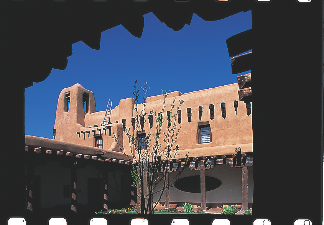

New Mexico

Dry conditions predominate in the southwest, as here in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Clear, bright days are predictable for much of the year, accounting for its long popularity with painters and photographers.

Desert

Rainfall is usually less than 10 in (250 mm), and in extreme places like the Atacama in northern Chile there may be no rain at all for years on end. Very reliable sunshine, and hence great temperature variation from day (very hot) to night (cool to cold). Duststorms possible, and in some desert areas these are seasonal and sometimes predictable. Coastal deserts experience fog, mist, and sometimes low cloud.

Examples: The Sahara, Namibia.

Lighting issues: Intense sun, blue skies. Early mornings and afternoons are key times for outside shooting.

Equipment issues: Extremes of heat and dust. Very sharp drop in temperature at night can cause condensation problems.

Death Valley

Below sea level at some points, Death Valley in California experiences an average of 2 in (50 mm) of rain a year and the highest mean temperatures in the US—and the highest record of 134°F (56.7°C). It has four areas of sand dune.

Mid-latitude light

Mediterranean

Probably the most comfortable, attractive climate for general photography. Rainfall is low and concentrated in the mild winter season, leaving the summers bright, sunny, and warm-to-hot. Some coastal locations, like San Francisco, have cool summers and significant fog in the mornings.

Examples: The Mediterranean coast, central California.

Lighting issues: High sunshine percentage and high reliability. Easy to schedule shooting in advance.

Equipment issues: No special problems.

New Orleans

Hot, steamy, but bright—early morning in the French Quarter of New Orleans on the Mississippi.

Humid subtropical

Cool winters, hot summers, with moderately high rainfall that is either throughout the year or concentrated in part of the summer. High summer humidity makes the height of this season uncomfortable and muggy. Liable to hurricanes and typhoons (same thing, different name) in late summer and early fall.

Examples: The US Gulf States, central and southern Japan.

Lighting issues: Variety of lighting conditions, low-to-moderate predictability.

Equipment issues: In summer, heat and humidity can be as high as in Tropical wet regions.

Aegean

A whitewashed Greek church against an intense blue sky on the island of Mykonos is archetypical of the Mediterranean ideal.

Marine

Summers cool to warm, winters never very cold. Rainfall is fairly high, but varies greatly from region to region, spread across the year but less in the summer. Unpredictability of everything is characteristic, and for photography this can be difficult. Weather is dominated by air coming in off the ocean, more often than not as depressions.

Examples: Western Europe, Vancouver, Washington State.

Lighting issues: Highly variable weather and difficult to predict. The light can change even several times in one day. Distance from equator causes a strong seasonal difference in the height of the sun and the length of the day.

Equipment issues: No special problems.

England

While the English weather is actually very varied, a blustery day like this, with a mixture of sunshine and showers, is widely considered typical.

England

The type of weather that draws the most complaints in marine climates like that of Western Europe is overcast, when depressions arriving from a long sea crossing can bring day after day of featureless, gray light.

Continental

Severe differences in temperature between the seasons, with warm-to-hot summers and cold winters—annual temperature ranges of around 50˚F (10˚C) are common. Precipitation across the year with a summer maximum; many snow-covered days in the winter.

Examples: The continental US and parts of central Europe.

Lighting issues: Length of daylight and height of the sun are similar to marine climates. Conditions moderately predictable.

Equipment issues: Severe winters can give subarctic conditions.

Arctic and mountain light

Subarctic

Huge area of the Earth’s surface but very small population. Long, bitterly cold winters, very short summers, brief spring and fall. Summer days are long, winter very short. Low precipitation concentrated in warmer months, but long-lasting snow cover in winter.

Examples: The Russian taiga, much of Canada and Alaska.

Lighting issues: Very long daylight hours in summer allows extended shooting, but very short days in winter are restrictive. The sun is never high, so clear weather very attractive. As with Arctic regions, possibility of aurora borealis.

Equipment issues: Cold and condensation are the main problems.

Arctic and Antarctic

Never warm and the winters are bitterly cold. The main feature for photography is continuous light in summer and continuous darkness in winter. Tundra is the part bordering the ice caps.

Examples: Greenland, Antarctica.

Lighting issues: By definition, winters are essentially one long night, although one special feature is the aurora borealis. Summer days move from one long sunrise to one slow sunset, with the sun’s path traveling around the horizon.

Equipment issues: Severe cold.

Lapland

The winter of northern Sweden is characterized by snow cover and Arctic conditions—sometimes as benign as this clear afternoon from a dogsled.

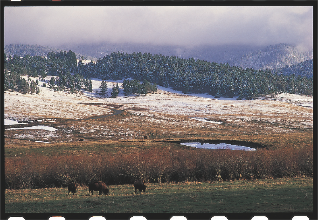

Mountain

Mountains intrude so much into the surrounding climates that they create their own general group of climates. It varies greatly, and in any one region is arranged vertically. As a rule of thumb, above about 5,000 ft (1,500 m), mountains create their own climates. It is difficult to generalize, but characteristics are low pressure, high UV, and intense sunlight, leading to high contrast in both light and temperature between sun and shade. Thin air gives a high temperature range from day to night, also. Precipitation is often higher than in the surrounding lowlands because the mountains cause air to rise and lose its capacity to hold moisture. Often this is on the windward side only, while the lee stays drier. There may be special mountain and valley winds.

Examples: The Rockies, the Himalayas.

Lighting issues: High altitude means strong UV and so blue distances and shadows. Thin air gives high contrast in sunlight, so expose for lit areas, not shadows. Weather often unpredictable, so light can change rapidly according to cloud cover.

Equipment issues: Physical protection against knocks is a priority, particularly when climbing is involved. High altitude means possibility of cold and condensation problems, especially at night.

Himalayas

At 16,400 ft (5,000 m), the visibility in fine weather is exceptionally good—the atmosphere is thinner than at sea-level, with 50% of the oxygen. The strong blues are due to the correspondingly high UV content.

Himalayas

Weather, light, and temperature shifts can be rapid and distinct at these altitudes (here, in western Tibet, at 19,700 ft/6,000 m). Clouds passing in front of the sun change the lighting more dramatically than at sea-level because of the greater difference between light and shade.

Mount Fuji

This image of Mount Fuji combines a number of “ideals,” including the season (snow-capped mountain), weather (clear, with good visibility), and light (just after sunrise).

Middle of the day

From late morning through to early afternoon (the exact times will vary depending on latitude and the time of the year) the sun is high in the sky. Many photographers regard this time of day as providing the least appealing light, and there are good reasons for this. However, it’s not necessarily time to put away your camera and wait for more photogenic lighting conditions.

When the sun is high in the sky, shadows are very short. With little or no discernible shadow, landscapes will not benefit from the modeling effect (which helps to emphasize undulating form) that is apparent when the sun is lower in the sky and any shadows cast are a great deal longer. Furthermore, if the sun is strong (and it will be at its strongest at this time of day), many scenes will have high contrast and a very wide dynamic range, making it difficult to capture detail in both highlight and shadow regions. This can often result in images that are difficult to “read,” with dark shadows and bright highlights obscuring important, “signposting” detail.

Photographing people when the sun is high in the sky also has its drawbacks. Your subject’s eyes will usually be cast in shadow (either by the subject’s own forehead and eyebrows), his or her nose may well appear ungainly, while the harsh light itself is not particularly flattering on certain skin colors.

Setting aside these technical drawbacks, high sun also has a reputation for producing bland, unexciting images. If you flick through a series of photographs, it’s likely that the ones that grab your attention most are those in which the light is dramatic or unusual. With its consistency in terms of light levels and quality, high sun is rarely striking.

What, then, does midday light have to recommend it? Well its greatest asset is that it can produce crisp, clear images, particularly when the air is clean. Shapes are clearly defined and colors are accurately and brightly rendered. And while horizontal subjects don’t benefit from any modeling effect, vertical surfaces, on the other hand, benefit from raking shadows, which help emphasize form and texture.

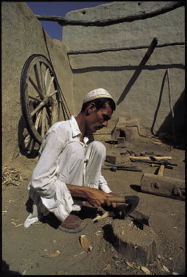

Holding the highlights

The contrast range in this shot of a Pathan craftsman was high at about 6 stops: the highlight reading, taken from his shoulder, was f/32; the shadow reading, taken from his neck, was f/4. However, his white clothes are such an important part of the image that they control the exposure setting; overexposure would be unacceptable. This exposure gives deep shadows, but the viewpoint was chosen so as to keep these small.

Vertical surfaces

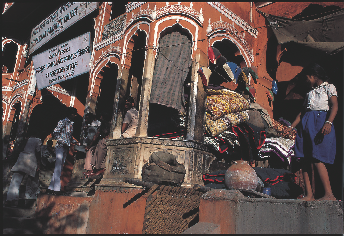

A high sun gives raking light on walls and other vertical surfaces, and, in the case of important texture such as the bas-relief here, can be extremely useful. The effects shift rapidly, however, so timing is critical. As the sun passes over a building, the light leaves one wall and passes to the opposite.

Graphic pattern

Bright, clear weather adds to the complexity of this street corner in Jaipur, India, by throwing extremely dense shadows. The stark, graphic effect produced is visually interesting in itself.

Morning and afternoon

The quality of light during the morning and afternoon, when the sun is lower in the sky, is favored by many photographers. The oblique angle of the sunlight, combined with the extra distance it has to travel through the atmosphere, is flattering for most subjects—shadows are less harsh and the softer, warmer light can introduce a pleasing glow to people’s skin, making it an ideal time for portraits. For landscapes and many architectural shots, the low angle introduces that all-important modeling effect which helps to define the scene.

At the same time, although less dramatic than the light at dawn and dusk, there is less chance of an orange color cast, and the light can be relied on to produce neutral results if accurate colors are important.

At these times of day the photographer is also able to experiment with the position of the camera in relation to the sun. Shooting into the sun, with the light behind, or to one side, are all possible, and will produce very different results, each of which is covered in more detail later on.

Finally, a low sun is less harsh than that at midday, resulting in scenes with less dynamic range, making it easier for the camera to capture detail in both highlights and shadows.

Shooting down

An overhead camera position can be a good option in morning or afternoon light. In this case, the contrast is usually much less because of the ground, or whatever surface the subject is resting on, but the texture remains strong. In addition, the long shadows make for interesting graphic compositions.

Wall details

Cross-lighting reveals texture at its strongest. Just as some vertical surfaces receive this at midday, others are at their best early and late in the day, as with this bronze fitting on a wooden wall. Here, the window of opportunity lasted only a few minutes before the shadows covered everything.

Horizontal light and shade

The visual play between highlights and shadows is an important component of photographs taken at these times of day. Shooting at right angles to the sun makes the most of this effect, and adds a linear, horizontal component to the image.

Using shadows

The shapes cast by shadows when the sun is fairly low can be put to good graphic use. In this morning shot of an old French abbey with a garden of lavender, the foreground shadow makes a solid base for the composition; the middle-ground shadows of trees suggest the unseen forest at right; and the shadow cast by the conical roof continues the lines of the hill beyond.

Sunrise and sunset

Images shot at sunrise or sunset can produce dramatic results, but it’s very important to do some homework, particularly if you have a specific location in mind. You may, for example, come across a breathtaking scene during the day which would be enhanced by capturing it at sunrise. Yet having taken the trouble to get up early in good time to catch the sunrise, you find that the sun is in the wrong position and all the wonderful detail that was apparent during the day is obscured by flat, dark shadows. Scout your locations in advance and work out in which direction the sun will rise. You may find that although the scene is not suitable for a dawn shot, it does lend itself to a sun set.

With the sun so low in the sky, you’ll find that the scene is actually darker than it appears, as our eyes are so good at adjusting to the available light. Always take a tripod and shutter release cable, or alternatively find something suitably sturdy on which to rest the camera. Although the sun may not be particularly strong, there is still likely to be a wide dynamic range throughout the scene, particularly if you’re shooting into the sun. Take a reading from the sky with the sun just out of view. Recompose and take the shot. Check the histogram and highlight warning screen to ensure there aren’t too many blown highlights and that dark areas of the image still retain detail. If necessary adjust the exposure and take another shot.

Warm, rich color

Exceptionally clear air keeps the sun bright, even when it is on the horizon and at its reddest, as in this shot of Monument Valley. The strongest colors appear with the sun behind you and the camera. You can avoid the problem of showing your own shadow by positioning yourself so that it falls in the distance, not on foreground features.

Silhouettes

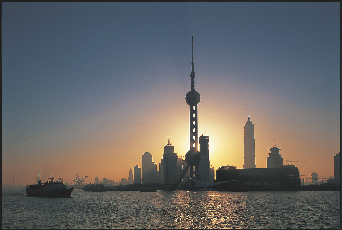

Shooting into the sun as it rises or sets creates obvious opportunities for silhouettes. These are easiest with a wide-angle lens, which makes the image of the sun small, and so easy to hide behind a feature such as this Shanghai tower.

Watch the white balance

Make sure that the camera’s white balance is set so that it does not compensate for the warm tones of a low sun, or the image will look strangely unsunset-like. This happened with an Auto setting (top), in contrast to a straightforward Direct Sun setting (bottom).

Twilight

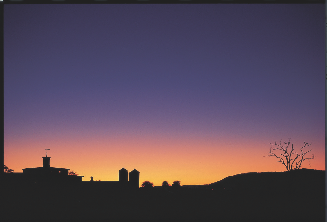

Twilight is the relatively short period of time that exists just before the sun has risen over the horizon or just after it has set. Exactly how long this lasts is down to your latitude, while how the sky appears will depend on the atmospheric conditions. If the sky is clear, you’ll be rewarded with a smooth gradation of color, starting with warm reds and oranges surrounding the sun, gradually fading to the cooler violets and blues, and eventually to black.

As with sunrise and sunset, it pays to get to your location early, which if you’re shooting at the beginning of the day may well mean arriving while it is still dark. So plan your trip in advance and assemble all of your equipment before going to bed! Exposures are likely to be relatively long, so you’ll need a tripod and remote shutter release.

With the sun actually out of view, you need to consider carefully your white balance setting. If you’re shooting Raw, which is recommended no matter what lighting conditions you’re working under, the white balance setting is less of an issue; if, however, you’re shooting JPEGs (perhaps with a view to printing directly) experiment with the setting until you get the result you’re happy with. The lower (or cooler) the setting, say around 2800K, will result in cooler, bluer images, which reinforce the tones commonly found at these times of day.

In terms of composition, remember that you’re going to be using exposures as long as perhaps 30 seconds. You can use this to your advantage. The movement of waves, for example, under long exposures takes on a smooth, cloudy appearance, while car lights can create attractive light trials.

Wide-angle or telephoto?

Experiment with both wide-angle and telephoto lenses, or both ends of the zoom range. Wide-angle views take in more of the height of the sky and capture a wide range of color. Telephoto shots, with a narrower angle of view, can only take in a small part of this; perhaps only a single color.

Shading of the sky

A clear sky at dusk or dawn acts like a smooth reflective surface for the sun as it lies below the horizon. The light shades smoothly upward from the horizon, and this effect is most obvious with a wide-angle lens, which takes in a greater span of sky. For example, while a 180 mm telephoto lens gives a limited angle of view of only 11 degrees, a 20 mm wide-angle lens gives an angle of view of 84 degrees.

Reflections at dusk

Shooting from almost at water level enhances the delicate tonal gradation before night falls over the Guiana Highlands of Venezuela. What makes this view attractive is that almost all the color has been drained from the scene.

Clouds at twilight

Added to the basic lighting condition, clouds are fairly unpredictable in their effect. If continuous, they usually destroy any sense of twilight, but if broken, they reflect light dramatically: high orange and red clouds create the classic “postcard” sunset. One of the things that becomes clear after a number of occasions is that clouds at this time of day often produce surprises. The upward angle of the sunlight from below the horizon is acute to the layers of clouds, so that small movements have obvious effects. On some occasions, the color of clouds after sunset simply fades; on others, it can suddenly spring to life again for a few moments—a good argument for not packing up as soon as the sun has set.

Blue intensity

When the sky is not red or orange at sunset or sunrise, an overall blue cast is typical, as in this winter scene.

Keep shooting

After the sun has set, even when you think you’ve captured the image that you had in mind from the outset, keep shooting if there’s any light at all left to shoot by—shooting in twilight is full of surprises and you never really know when the light has gone for good. You might think it’s all over only to discover a full moon rising, and a whole new set of possibilities opening up to you.