19

A Prairie Home Companion

I WAS CURIOUS ABOUT THE invisible radio audience who listened at 6 a.m. I wanted them to be friends, so one morning I announced tryouts for the Jack’s Auto Repair softball team and the next Saturday a big crowd showed up at a ballfield in south Minneapolis, and we chose up sides and played a dozen innings, drank a case of Grain Belt, and went home. But the idea took hold. A team of strangers spontaneously formed. John and Ann Reay took down names and phone numbers, and we held a practice and played against the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra team, their conductor Dennis Russell Davies pitching. We took the game seriously, regardless of ability. Lots of infield chatter, throwing the ball around the horn. Serious attitude. Remorse at your errors, no joking around until later. The Minnesota Orchestra sent over a team, the Walker Art Center, the Guthrie, serious play, a case of beer afterward. Friendships formed. When Prairie Home got big-time, touring, Sunday afternoon softball disappeared but some friendships remained. Russ Ringsak, an architect, a Harley and blues guy, wound up becoming a friend. He once built a long twisting snow slide on a hillside behind his house with banked curves designed for maximum thrills: you jumped on a plastic saucer and the slide threw you around for a couple minutes. He told a joke every time he met me. He got fed up with architecture and came to work for Prairie Home as our truck driver for the last twenty years or so, drove the big red Peterbilt cross-country and wrote up pages of notes on each broadcast city and, when he got sick and needed to retire, he played electric guitar and sang “Six Days on the Road” at our last broadcast at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. The loyalty of good people like Russ and Tom Keith and Kate Gustafson—I took it for granted at the time and now I’m astonished.

In the summer of 1973, thinking this was something a radio guy should do someday, I rode the train to Nashville with my friend Don McNeil from the softball team to see the Saturday night broadcast of The Grand Ole Opry at the Ryman Auditorium, which was completely sold out that night so we stood in the parking lot behind the hall and listened to it on WSM from the radios in nearby pickup trucks. There was a whole crowd of us out there. We got to see Loretta Lynn’s tour bus pull up in the alley and she herself step out and walk by in glittering white gown, long black hair, and the crowd parted for her, nobody asked for an autograph, a few people said quietly “Hey, Loretta,” and she smiled and picked up her skirts and went around back to the stage door. The Ryman wasn’t air-conditioned and the windows were wide open, and when we ducked down behind a low stone wall we could see the lower halves of performers on stage, Dolly Parton and Roy Acuff and Bashful Brother Oswald, and almost all of Stonewall Jackson. My hero Marty Robbins sat mugging at the piano and sang “Love Me,” grinning on the falsetto part in the chorus, and then jumped up and did “El Paso,” strumming a little Spanish guitar up on his shoulder. Listening to the music from car radios in the parking lot surrounded by reverent fans on a hot summer night, I felt happy, excited, even exalted. I thought, “I’d like to do that someday.”

The next spring I went back to Nashville and wrote a piece about the Opry for The New Yorker. Roger Angell handed me over to a fact editor, Bill Whitworth, knowing Bill is from Little Rock and knows country music, and Bill at the time was the trusted deputy of William Shawn, the editor, and so the assignment was made, though Mr. Shawn’s interest in country music was slight at best. On this daisy chain of connections my whole career hangs. If Roger had handed me to an editor from Connecticut, or if Whit-worth had fallen out of favor with Shawn, or if Shawn had mentioned the Opry to Lillian Ross and she said, “You’re out of your mind,” I’d be wearing a TSA badge and patting down men with suspicious pants at the airport.

I went to the Friday night show and skipped the Saturday night because Richard M. Nixon would be there, trying to slip the bonds of Watergate, and I didn’t care to write about him. I sat in the balcony of the Ryman and watched the sequined ladies with big hair, men in gaudy suits, commercials for chewing tobacco and pork sausage and self-rising Martha White flour and Goo Goo Clusters, Cousin Minnie Pearl (I’m just so proud to be here! ), the red-barn backdrop, the haze of cigarette smoke, the fans and their flash cameras, the announcer in his funeral suit, and I resolved to go home and start up a Saturday night show of my own. I wrote the piece, Bill Whitworth shepherded it into print between ads for Chanel No. 5 and Cartier diamonds and Cricketeer yacht wear, and I went up the stairs to Bill Kling’s office at KSJN to talk.

Kling kept meetings short. He had a low tolerance for the prefaces and digressions by which people show they have a liberal arts education. He was a true believer in radio, listened to it religiously, and in public radio, surrounded by malcontents, he got excited by good ideas. I proposed the show and he told me to go right ahead. Saturday at 5 p.m., between the Met Opera and the New York Philharmonic broadcasts. He called in Margaret Moos, who worked upstairs in publicity, and asked her to produce it. “Have fun,” he said. It was a ten-minute conversation. Saturday evening was a dead zone in radio, but I was in a sinking marriage and had nothing to lose.

A few years later, I invited Mr. Shawn to come to Minnesota and play piano on the show, and he wrote back: “Unfortunately, I don’t travel and in my opinion I don’t play well enough, so I must decline.” A perfect Shawn sentence, not one unnecessary word in it.

Twenty years later, when the Ryman Auditorium reopened after renovation, Prairie Home was the first show back in, a classic show with Chet and the Everlys, Robin and Linda Williams, Buddy Emmons, Vince Gill, and Mary Chapin Carpenter, and I just stood off to the side and waved them on, one after the other.

The name A Prairie Home Companion came from a Norwegian cemetery in Moorhead, opened in 1875 by a man named Oscar Elmer who planned to make his bundle and head back East, leaving this godforsaken treeless plain behind, but then his brother John died, apparently a suicide, and the tragedy made up Oscar’s mind to bury his brother in Moorhead and call the cemetery Our Prairie Home. And Oscar wound up staying. The story appealed to me—Norwegians establishing a graveyard as a sign of loyalty—so I took the name and stuck “Companion” on it as a dark joke. I felt about radio as Mr. Elmer felt about North Dakota. Radio was a temporary job until I could finish my novel about a small town in Minnesota, but then I lost the manuscript in the train station in Portland, left it in a briefcase in the men’s toilet, went back and it was gone. The story of Oscar and his cemetery spoke to me. Here we are. Life has its sorrows. Make something beautiful out of it.

I wanted an ecumenical show and Kling wanted a live broadcast, which eliminates the tedium of editing. I’d grown up with commercial radio so I invented sponsors, the Café Boeuf, the Fearmonger’s Shop (serving all your phobia needs), Guy’s Shoes, and Powdermilk Biscuits. (If your family’s tried ’em, you know you’ve satisfied ’em, they’re the real hot item, Powdermilk . . . Heavens, they’re tasty and expeditious.) I had musician friends who were game—Butch Thompson was a classmate at the U and I met Bill Hinkley and Judy Larson busking on the West Bank. And Robin and Linda Williams playing a college coffeehouse, singing to fifteen people with pinball machines dinging and cash register ringing. I knew Philip Brunelle, Vern Sutton, and Janis Hardy from the Center Opera Company. Vern and Janis had big voices and could improvise if I wrote a script about singing furniture, plus which they could do speaking roles. Vern did weaselish characters, con men, card sharps; Janis could sing precisely a quarter-tone sharp or flat and convulse the audience. One week she brought her dog Freckles and they did “Indian Love Call,” Freckles howling when Janis hit a certain note. Philip at the keyboard could sight-read or play by ear or both. The three of them could set any words to music in any style, on the spot, a pork chop recipe à la Chopin, a list of cocktails à la Philip Glass.

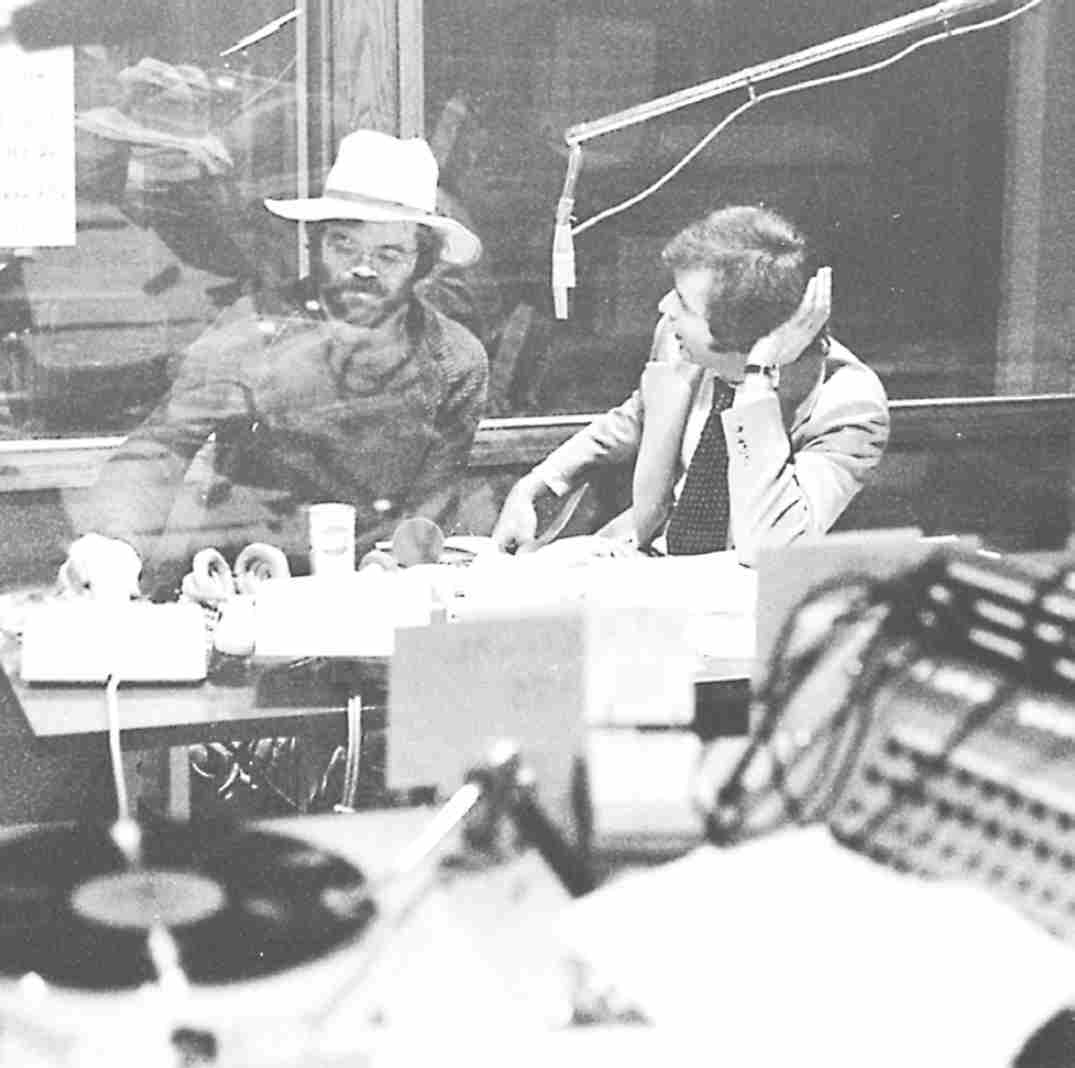

GK and Bill Kling, KSJN studio, 1975.

The music was sociable, old jazz, love duets, bluegrass, ballads, nothing that took itself too seriously. No Dylan. His “Half-wracked prejudice leaped forth, ‘rip down all hate,’ I screamed. Lies that life is black and white spoke from my skull I dreamed ” was like stuff I wrote in my sophomore year at the U. Why repeat it? Go for the visceral, skip the gaseous emanations of sensibility.

I was the writer with the idea, but the musicians were the ones who made it real, as I very well knew. Bill and Judy did “Barnyard Dance” (It was late last night in the pale moonlight, All the vegetables gave a spree. They put out a sign that said, ‘The dancing’s at nine’ And all the admission was free.). Soupy Schindler played jug, did a steam locomotive on his mouth harp. Vern Sutton sang “Curfew Must Not Ring Tonight” about Nellie hanging on to the clapper of the church bell as the hangman waited to hear it so he could execute her daddy. Butch played “How Long Blues.” And so we proceeded down the road, not knowing what a fine education it would turn out to be. It went on the air on July 6, 1974, admission $1, 50 cents for kids. Margaret Moos sold tickets and her sisters Martha and Becky ushered, and Margaret quickly became boss because she knew what to do and we didn’t. I was the doubter. I thought it might last the summer. I wore a white suit and a big white hat to make myself look authoritative, but I was in over my head, which you could see if you went to the show, which luckily not many people did. Attendance at the first show was thirty-six, half of whom left at intermission. On the radio, it sounded better than it was; on stage, there was a grim-faced man in a white suit struggling to have a good time. And the next week I got the first fan letter, from a listener in St. Cloud.

We enjoyed the show Saturday night and hope you were happy with it all because it seemed to work out real good. You might want to try that sort of thing again. I heard most of the show while getting my file cabinet organized, the appliance guarantees, unpaid bills, vacation brochures, and all such. I don’t really believe it will work, but it is good to purge oneself on occasion and feel you have done good. People need this sort of thing. After the show Romy and I went downtown for dinner.

Tell those people to have it quit raining.

Fred

It was a folk music show that went on week by week, live, unedited, four microphones, no rehearsal, no stage monitors, songs thrown together on the fly and mixed on an 8-channel mixer. I tried to sound friendly because that’s what Bob DeHaven of “Good Neighbor Time” sounded like, so I tried to chuckle as I introduced the acts and promoted Jack’s Auto Repair (All tracks lead to Jack’s) and the Chatterbox Café (Where the elite meet to eat), Ralph’s Pretty Good Grocery (If you can’t find it at Ralph’s, you can probably get along without it), the American Duct Tape Council (It’s almost all you need sometimes) and the Federated Organization of Associations (which became the Associated Federation of Organizations and then the Official Federated Organization of Associations), Bertha’s Kitty Boutique (For persons who care about cats), and the Catchup Advisory Board (These are the good times, strong and sure and steady. Life is flowing like catchup on spaghetti). Commercials freed us from the academic formality of public radio and let us talk about indigestion and sore feet, cat hair, bad breath, and the need for adhesives. Sponsors such as Bebopareebop Rhubarb Pie, Thompson Tooth Tinsel, the Coffee Advisory Board (Smells so lovely when you pour it, you will want to drink a quart . . . Keeps the Swedes and the Germans awake through the sermons).

Ray Marklund, an electrician for Northern Pacific railroad, was our lone stagehand (unpaid, at his own insistence; he said, “I don’t want to have to take orders from people who’ve got no idea what they’re doing”). He carried a toolbox and could solder wires and unlock doors, and once he unlocked a piano. He liked jazz more than bluegrass, but he stuck with us because he could see that we needed him. We played little theaters—one hundred or so capacity—and I learned that Minnesota audiences are thoughtful and cautious and don’t laugh unless people near them laugh. I learned to get their attention by speaking softly. I took no pay at the start because I felt unnecessary; the acts got $50 or $75 each—without them, there’d be no show. We finished our first year of shows, and I popped a cork in a real champagne bottle and it flew sixty feet to the back row and struck a four-year-old boy named Ben Ellingson, who cried out in surprise. I took the microphone up the aisle to apologize to him. (The family attended our twenty-fifth anniversary show; Ben was fine and had graduated from grad school.) For several summers, we played in a downtown park a block from the main fire station, across from the Church of St. Louis. Bells rang at 5 p.m. and now and then fire trucks came screaming past and we made ourselves ignore them. Once, an old drunk with a harmonica wandered in and tried to join the show and had to be restrained. Our audience, mostly Minnesota liberals, liked him because he looked like a Dust Bowl refugee, but he was a lousy harpist and a worse singer. Much to the liberals’ displeasure, we ushered him out. Some of them protested, but we were a radio show, not a treatment program, and the guy couldn’t play harmonica.

Our first engineer was a former Marine sergeant, Tom Keith, who mixed the sound until we added him to the cast doing sound effects, heart-rending loon calls, gunshots, talking dogs and hysterical chickens, and various varieties of flatulence. He did silly things with great dignity. I was a self-conscious English major and he made me a storyteller who could have a Chinese ICBM cross the Pacific heading for a Scout camp in Aspen where loons sing “Kumbaya,” but breeding dolphins east of Oahu emit high-pitched euphoric cries that confuse the rocket’s guidance system and it lands amid nougat storage tanks in a series of splats and splorts, and thousands of aspen release a cloud of aspen gases that are ignited by a Scoutmaster lighting an exploding cigar as a glockenspiel plays Bach. That sort of thing.

Mr. Ray Marklund, stagehand, seated at GK’s desk, 1984.

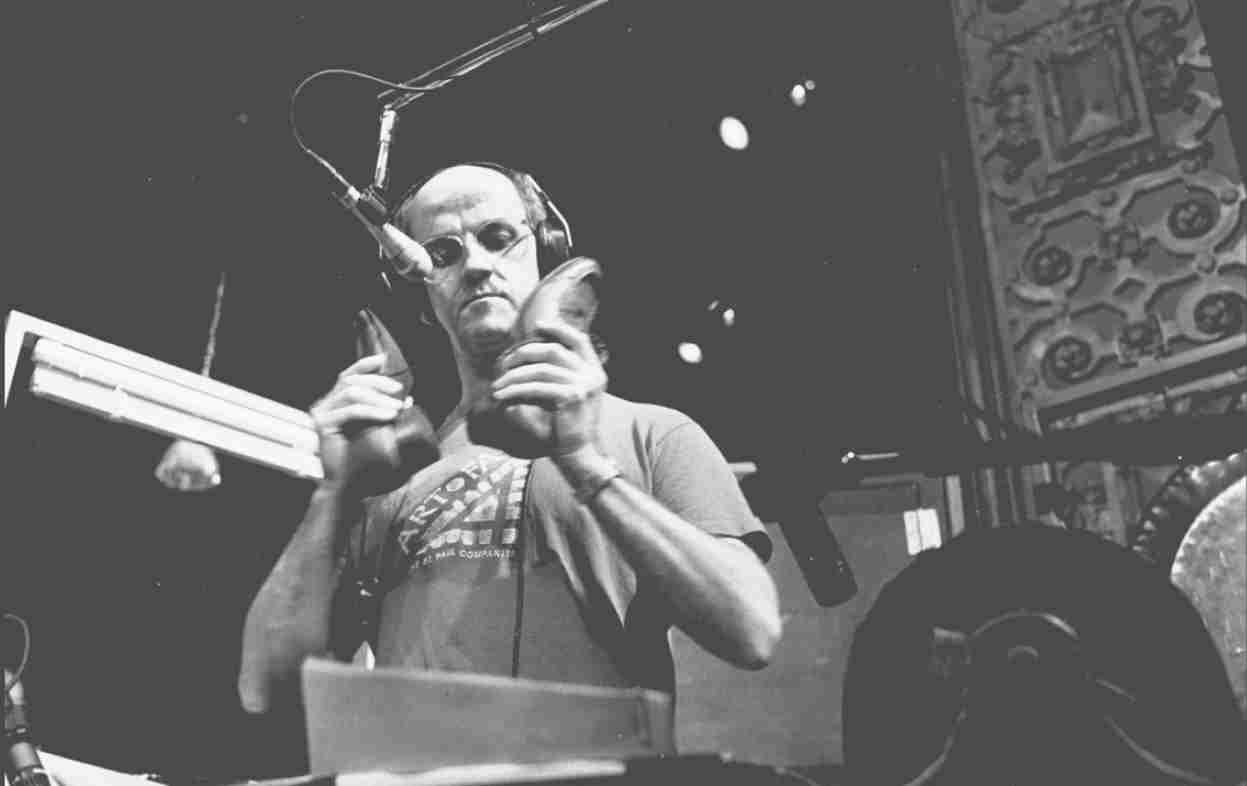

Tom Keith at the SFX table.

We rehearsed in my living room, Bill and Judy on the couch, Cal Hand playing dobro, Rudy Darling fiddling in the archway of the dining room, sometimes Mary at the piano, my little boy sitting enrapt in the middle of the floor, buoyant music in a sad household. I kept writing for The New Yorker, shipping the stories off, waiting for Roger’s response— his gentle rejection letters—didn’t seem entirely successful was as harsh as he got—and his acceptance letters: FRIENDLY NEIGHBOR is awfully good, and we are delighted to take it, of course. It grows gently but strongly as one goes along, and it’s like nothing else I have ever read. And Mr. Shawn wrote soon thereafter, saying, “This is the sort of deadpan humor one doesn’t see much of anymore. The more you write for us, the better.”

Lavish praise on a New Yorker letterhead and then a generous check and we were rich for a month or two, and then went back to oatmeal, hot dogs, and spaghetti. We lived in St. Anthony Park, a Lutheran neighborhood, and I could let my little boy wander out through the backyards and find his playmates and a few hours later a mom would call and ask if it was okay if he stayed for lunch. No need to hire child care, with Lutherans around. I sat at my Underwood with a faint O and off-kilter F and P and wrote the show.

I broke up with Mary in 1976. There was no anger, only silence, which we each misinterpreted as rejection. A simple language barrier, the inability to say what you feel. We had some good times in our little house with the gazebo on the hill where friends came for bratwurst and beer and played sweet old songs. She gave piano lessons to the children of friends. She took up guitar. We plotted the first broadcast of A Prairie Home Companion and she picked out “Hello, Love” as the theme song. We never made such a cheerful home as her parents had. I married for happiness of course and the mystery of love, and what I found was loneliness, which made me think there something wrong with me, and then I found someone who wanted to be with me, and so I left one mystery and walked into another. I packed up my clothes and papers. Our son said, “Couldn’t you and Mom take turns being right?” Mary said something about counseling. But we had had so little to say to each other for so long, each of us burdened with remorse; where does one start? I drove away with no words of farewell and we hardly ever spoke again.

The show hit the road in a Winnebago motor home for twelve shows in twelve towns in twelve days, in Minnesota, Iowa, Wisconsin, pitching a tent each night—the Powdermilk Biscuit Band and I, and did fifty live broadcasts that year, with a shifting cast of Bill and Judy, Dakota Dave Hull and Sean Blackburn, Rudy Darling, Peter Ostroushko, Robin and Linda, and Stevie Beck, the Queen of the Autoharp. Eventually we settled on a house band of Bob Douglas, Mary DuShane, Adam Granger, and Dick Rees, a classic mando/fiddle/guitar/bass string band that, thanks to my ignorance of music, enjoyed a lot of freedom, covering gospel, swing, and old-time fiddle tunes. They started out at $40 apiece per show and got up to $150, not bad for freelance folkies.

Bob knew dozens of gospel songs, like “Prayer Bells of Heaven (oh how sweetly they ring)” and “Anchored in Love” (The tempest is o’er, I’m safe evermore, what gladness what rapture is mine. The danger is past, I’m anchored at last. I’m anchored in love divine). Tom Keith mixed sound and drove. I sang bass on the gospel stuff, and now and then sang something of my own. Once a boy in the first row threw up as I sang, The old radio, the old radio that held a place of honor in our home of long ago. The folks are dead and gone and I am moving on, sitting all alone by our family radio. He had the flu, his mother explained later. I stood and talked to give the band a chance to retune, look at the chord chart, get a drink of water, use the toilet, so I said: I am from Minnesota, a state that ranks forty-seventh in the use of irony, a serious state where every year, nature makes serious attempts to kill us, and then it’s summer and time for giant carnivorous mosquitoes, who no bug repellent even discourages. A crucifix helps but you have to hit them really hard with it. Why do I tell you this? Because our sponsor, Powdermilk Biscuits, is the only baked product that gives shy persons the strength to get up and do what needs to be done. . . . Heavens, they’re tasty! And expeditious. And so on.

In Duluth, we played the train depot, using baggage carts for a stage. We played a Lutheran church in Sioux Falls, for which I wrote a Lutheran anthem:

Episcopalians are proud of their faith,

You ought to hear ’em talk.

Who they got? They got Henry the 8th

And we got J. S. Bach.

Henry the 8th’d marry a woman

And then her head would drop.

J. S. Bach had twenty-three kids

’Cause his organ had no stop.

I was raised to keep a lid on it,

Guard what you say or do.

A Mighty Fortress is our God

So he must be Lutheran too.

That night we got snowed in, slept on the floor of the Sunday School wing with the Good Shepherd looking down from the wall. We made it through on snow-drifted roads to Worthington and Mankato. When the audience had had enough songs about the lonesome whistle’s wail and When I’m dead, let your teardrops kiss the flowers on my grave, Tom Keith jumped up on stage with me and we did a story about dogs, engines with piston problems, a mammoth catapult, giant condors, demented elephants, stuttering butlers, exploding beer bottles, Alpine horns, fast trains—he was game for anything. I was merely the narrator, the enabler, winging it toward a big finish (a ship departing, seagulls, surf). People loved Tom. He had been a mere engineer and we made him a star. People asked for his autograph, so we had 8 x 10 glossies printed up.

Judy Larson, Bill Hinkley, GK, Bob Douglas, Rudy Darling—Worthington, MN, 1975.

We lived in close quarters on the road and had to endure Bob Douglas’s incessant practicing of Irish hornpipes and jigs on the mandolin and, to distract him, we worked up a Sons of the Pioneers number, “Blue Shadows on the Trail,” in five-part harmony with some tricky passing chords in it, and we got it almost to perfection so we sang it in Moor-head, or started to sing it, and hit a chord so awful we all collapsed in helpless laughter right around the line “a plaintive wail in the distance.” It wasn’t plaintive, it was putrid. Rudy fell on the floor and could not get up. The audience had never seen professional musicians fall apart physically like this before. To restore sobriety, we swung into On Jordan’s stormy banks I stand and cast a wishful eye to Canaan’s fair and happy land, where my possessions lie. A song about death always settled us down. We never ventured into “Blue Shadows” again. We knew that if we did, we’d see the plaintive wail approaching and we’d crash into it.

We traveled by motor home mostly, but once a small corporate jet was put at our service to fly up to do a tent show in Bayfield, Wisconsin. We did two shows and were driven to the airport for the flight home. The airport manager said, “Frank is on his way.” We asked who Frank was and he said, “He has to drive a truck ahead of the plane to scare the deer off the runway.” We boarded the plane and Frank raced down the runway and we followed, the plane took off, and Adam took a deep breath. I asked him what he was thinking. He said, “I was thinking I might be the answer to a trivia question: who was the guitarist on the plane that crashed and killed Garrison Keillor.”

I doubted the show would last but we drew capacity crowds and I was curious to know what the appeal might be, so I kept going. It sure wasn’t my personality. I was a tall sourpuss with a big beard and a white suit, looking like a Confederate general on trial for his life. But in 1976, the News from Lake Wobegon came along, and soon made the jump from one-page letter to fifteen-minute monologue—Well, it’s been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon—based on the four seasons, the school year, the national holidays, and the liturgical year—starting with a word about the weather, then the news of the Norwegian bachelor farmers, the Thanatopsis Society, the Sons of Knute lodge singing: Sons of Knute we are, sons of the prairie, with our heads held high in January, hauling our carcass around in big parkas, wearing boots the size of tree stumps. And with the arrival of Lake Wobegon, the show took on a clear identity.

I was out to play with the familiar, talking about a place where you could count on others in time of need as Mother had during the war. Religious and ethnic differences aside, it was tightly knit and had little tolerance for pretense. Satire was a sign of good health. Mutual benefit was fundamental, and industry and loyalty and a decent reverence for the natural world, while waste was abhorrent and cruelty not tolerated. Midwestern modesty prevailed. Children were brought up to be deferential and self-effacing and behave appropriately, which, it was assumed, you knew without being told. Nobody encouraged you to follow your dream. Spiritual longing was a private matter, as were grief and regret.

The town motto: Sumus quod sumus (We are what we are). Grace was the town librarian, Gary and Leroy the town constables, and Bud ran the snowplow. Dr. DeHaven was the physician, though he was seldom mentioned; he took a “Let’s wait and see what develops” approach to disease. A central figure was Father Emil of Our Lady of Perpetual Responsibility church, and to offset his sternness, I placed a nun in the church, Sister Arvonne, in honor of my friend Arvonne Fraser, a cheerful liberal and optimist despite personal tragedies, still canoeing, still smoking, into her late eighties. Her adversary, Father Emil, is strict and brusque: to the weeping girl who found out she was pregnant, he said, “If you didn’t want to go to Chicago, why’d you get on the train?” To the German Catholics I added, for dramatic interest, an equal number of Norwegian Lutherans led by Pastor Ingqvist. The Norwegians, ever status-conscious, vote Republican, and the Germans vote Democratic because the Norwegians don’t. The car dealers are Bunsen Ford and Krebsbach Chev, which means that Lutherans drive Fords and Catholics drive Chevies, and if you drive something else, people watch you very closely. Dorothy ran the café and Wally the Sidetrack Tap, and the Mercantile belonged to Cliff with his amazing comb-over, a piece of hair architecture. And it ended: And that’s the news from Lake Wobegon, where the women are strong, the men are good-looking, and all the children are above average. Like most of the best lines, it came out of nowhere. I woke up one morning and it was in my head.

I put Lake Wobegon in central Minnesota because my city audience knew the scenic parts of Minnesota, the North Shore, the Boundary Waters, the Mississippi Valley, and nothing about the midsection with all the hog and dairy farms. The town was founded by Father Pierre Plaisir who named it Lac Malheur for the pestilence of mosquitoes. It was later settled by Unitarian missionaries. The town was not on the map, having been left off by surveyors in the 1860s who had surveyed more of Minnesota than there was room for between the borders, so about fifty square miles had to be folded under. I said that Lake Wobegon took its name from the Ojibway word that means “the place where we waited all day for you in the rain,” and somehow people believed this and other historic details. I said that, in 1938, Babe Ruth appeared in an exhibition game with the Sorbitol All-Stars barnstorming team and hit a home run that cleared the center field fence and was never found. Near the ballpark stands the statue of the Unknown Norwegian with the stalk of quack grass growing out of his left ear, from a seed implanted there by the tornado of 1965, which no herbicide has been able to kill off. The Unknown was so famous in the 1890s that nobody bothered to put an inscription on the base, and now nobody can remember if he was a Swanberg or Swenson.

Because I assumed the show would end in a year or two, I didn’t keep orderly notes on the town; it was all in my head. The ball club was the Schroeders, then it became the Whippets. The town barber began as Jim, then became Bob. The town clerk was Viola Tors, though before she’d been a Tordahl. I had a hard time keeping the Tordoffs straight from the Tommerdahls, Thorvaldsons, Tollefsons, and Tolleruds, and sometimes characters migrated from one family to another. Val Tollefson was married to Charlotte and later turned up married to Florence. I had the same problem with Krebsbachs and Kreugers: Wally, the owner of the Sidetrack Tap, was sometimes a Krebsbach, other times a Kreuger. Carl Krebsbach is the town handyman, married to Marjie though once he was married to Betty. The Ingqvist family is complicated, sometimes appearing as Ingquist or Inkvist or Ingebretson, and the relationships are not clear. Roger Hedlund is married to Marilyn except for a while she was Cindy.

I made a crucial decision from the get-go that, instead of Cool, I was going for Sweet. I was clear on this. I was cool in college. Now that was over. One day, a security woman checking IDs at an airport lounge saw me coming and said, “Good morning, sunshine,” though she didn’t know me from Adam. She glanced at my driver’s license and said, “Have a good flight, darling.” This was in the South, of course. That woman’s “sunshine” shone on me for the rest of the day. On the flight that day, I sat next to a Black woman my age from Alabama, who was in a chatty mood. I said, “You’ve seen a lot of history in Alabama.” She said, “And it isn’t over yet.” We got to talking about Dr. King and his family, and she blurted out, “I just cannot forgive those children of his for never giving their mother a grandbaby. Four healthy children. I don’t know their sexual orientation, but you would think that one of them could’ve produced one baby for Mrs. King to hold. She died without ever getting those babies to hold in her arms. Do you have grandbabies?” I said, No. “I’ve got two,” she said, “and every time I look at them, that’s me.” She patted my hand. “I am going to pray for you to get grandchildren.” When the plane pulled up to the gate in Chicago, she touched my knee and said, “It was good talking with you, darling.”

In Minnesota, we don’t address each other as “darling.” I went to a big dinner of diehard liberals in Texas and was darlinged left and right and sweetied and even occasionally precioused, but if you were among Democrats in Minnesota, it feels like a meeting of insurance actuaries, a cold handshake and a thin smile and that’s all you get. We are wary of affectionate banter with strangers for fear we’ll end up with a truckload of aluminum siding or a set of encyclopedias. We’re burdened by the need to be cool. I decided early to do a Southern show up north. So I avoided the sardonic and ventured into sweetness. I wrote a song about the town.

Oh little town, I love the sound

Of water sprinklers in the evening,

The siren tune at 12 o’clock noon, or 12:04 if Bud is late.

And when you walk down Oak or Main,

Everybody knows your name,

They ask you how you are, you say, “Not bad, all right, I guess about the same.”

Wobegon, I remember O so well how peacefully among the woods and fields you lie—

My Wobegon, I close my eyes and I can see you just as clearly as in days gone by.

As the Sons of Knute say, “There’s no place like home when you’re not feeling well.” Or, as Clarence Bunsen says, “When you’re from here, you don’t notice it so much.”

The monologue took its place after intermission, and when I walked downstage and said, “It’s been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon,” the audience let out a soft sigh, as if an old uncle had returned. The key to the story was to maintain a modest tone, avoid smart and uppity language, stay in the background, as a Wobegonian would do. Every spring, a monologue about the sadness of leaving school behind. Every October, the glory of autumn days. In January, a long tale about heroic Minnesota winters, keeping warm by the exertion of wearing heavy clothing while shoveling the walk and throwing the snow up on the snowbank fifteen feet overhead, clothesline tied to our belts so that in case of avalanche, they could pull us out in time, watching for enormous icicles falling like daggers and also for coyotes who would take on a boy immobilized by heavy clothing.

Every week I felt their pleasure at the familiar. It was not an accurate story—for one thing, there was no profanity—I grew up among people for whom “Oh shoot” or “Fiddle” passed for curses, and so I don’t have an ear for it either. And death was rare. The hermit Jack died in his hunting shack in the woods, and a Norwegian bachelor farmer too, and my aunt Evelyn died in her sleep, but no main characters, and they tended not to get older either. Some of them remained in their late fifties for thirty years. There was genuine feeling and occasional tenderness among taciturn people, a man weeping for pride as his daughter makes a crucial jump shot in a game, old couples dancing at the Sweethearts Ball in an unmistakable embrace, the hush of Christmas Eve, the Catholics weeping as they sing “Stille Nacht” in their grandparents’ German. Myrtle and Florian Krebsbach drove toward Minneapolis to visit their son and fell into squabbling, and when he stopped at a truck stop for gas and bought a Snickers bar and came back to the car, he didn’t look in the back seat where she’d been napping and so he drove away, leaving her in the ladies’ john. Her anguish and his shame led to a joyful reunion, whereupon the battle resumed.

Lake Wobegon was a departure for me, I who once imitated Kafka and Lorca, and it led to sentimental songs that, ten years before, never would’ve occurred to me.

Look in every smiling face,

Keep the memory of this place,

And before we must depart,

Sing one chorus from the heart.

From this prairie, from this home,

We shall fly to realms unknown,

Carrying no souvenirs,

Just our memories and our tears.

We were amateurs, made no attempt to hide the fact. And we were proudly provincial. Chauvinism begins at home.

Minnesota is the best

University in the West.

Harvard University is pleased

To be called the Minnesota of the East.

Other songwriters sought the universal, and I embraced the ordinary. People came to the show and wrote greetings on slips of paper and passed them down front and I said hello to Jody in St. Joe and Benny in Nowthen and Will and Sonya in Minneapolis and I wished Rachel well on her graduation from St. Ben’s. And I wrote songs—not the best, but good enough.

M is for the falls of Minnehaha

I, of course, for Irving Avenue S.

N for Nicollet Mall and Nicollet Island

The second N is anybody’s guess.

E is for the street they call East Hennepin.

A is Aldrich Avenue Southwest.

Polis is a Greek word meaning city

And Minneapolis is the best.

It’s a bower of bliss on the Miss-issippi

And when all is said and done,

Now I see there’s one ZIP code for me,

And that is 5-5-4-0-1.

A small town was the lodestar. The show was never about peace and harmony, never about Daring to Be Me. It was always about loyalty. Be True to Your School.

We toured to the Fox River Valley and I wrote a song for Appleton. It was the Garden of Eden back when time begun. Eve took a bite of the apple for fun and said, let’s settle here in Appleton. A columnist the next week called it “shameless pandering,” but I thought it was funny. I was not out to deepen or broaden. I was a man at play.

I went dancing one night in East Lansing

We sowed wild grains across the Great Plains

Spent a wild youth in Duluth

Found euphoria and joy in Peoria, Illinois,

And my all in St. Paul—It’s you—that’s the truth.

In the early years, musicians doubled as actors and I walked around backstage, scripts in hand, and asked for volunteers. Some musicians were eager, others dreaded the thought. Bluegrass musicians preferred to stay in safe territory and not have to shout, “Allons, camarades!” and cross swords with a guy named Pierre who turned out to be a woman, but singers were always game, and so were bass players. Still, there was an awkward self-consciousness about it—and when I found out that George Muschamp and Molly Atwood, who lived across the street from me in St. Paul, were actors in the Children’s Theatre Company, I grabbed them and they were great and we never looked back.

I turned a New Yorker story of mine, “Lonesome Shorty,” into “The Lives of the Cowboys” about Dusty and Lefty and it went on for decades. Tom Keith did horse snorts and whinnies, the pouring of whiskey in the glass, the shuffling of cards, the slow tread of the big boots of the bully Big Messer as he approached, the cocking of his pistol, the slow leakage of gas from him despite his attempts to tighten his sphincter, the lighting of a match, the explosion that sends him crashing into the aspidistra, and all I had to do was write dialogue.

LEFTY: I got a confession to make, pardner. Whilst I was making that soup, I dropped a bar of soap in it by accident and by the time I fished it out, it was a fraction of its former size.

DUSTY: So that’s why you didn’t have any soup yourself.

LEFTY: I wasn’t hungry.

DUSTY: I wouldn’t’ve been either if I’d known there was soap in it.

LEFTY: Well, you ate two helpings of it.

DUSTY: Didn’t know it was soap soup.

LEFTY: You couldn’t taste it?

DUSTY: Tasted about as good as anything else you ever cooked.

LEFTY: Well, maybe I should make it more often then.

DUSTY: I guess you didn’t notice that there was more bourbon in the bottle last night than there was yesterday morning when it was practically empty.

LEFTY: What are you saying?

DUSTY: Take a wild guess.

LEFTY: Are you saying you pissed in the whiskey?

DUSTY: Nope. It’s horse piss. You drank three glasses of it, evidently you’ve forgotten what good whiskey tastes like.

LEFTY: Why in the world would you go and do a thing like that?

DUSTY: I’m trying to stop drinking.

LEFTY: So that’s why you didn’t have any.

DUSTY: It works!

Writing for The New Yorker was an uphill climb—shadows of Perelman and Frazier and Woody Allen on the wall—but with radio, the coast was clear: the greats were long gone—we had no competitors, nobody else did scripted comedy on radio. It was a walk in the park compared to my dad’s hard labors—working on the train, building our house, doing carpentry for others, raising a garden. I was the boss, so my work was never rejected except by me. Nobody said, “I’m sorry, but this is not you at your best.” Maybe it wasn’t, but we had a show to do and better and best don’t mean all that much when you’re the only café in town. Shut up and enjoy your pancakes.

I played the title role in Dr. Brad Triplett, Wildlife Urologist, performing a prostatectomy on a white-tailed deer and explaining to my adoring nurse Sharon that urine is how wild animals mark territory and so a urinary dysfunction also affects social standing and the ability to mate, which is why I gave up my lucrative practice in Winnetka to work the woods of northern Wisconsin—“Yes, the deer are overpopulated,” I said. “But a doctor can’t play God. We’re here to help, not to judge the worth of a life. A man has to follow his heart, and this is my mission. Urine is in my blood somehow.”

I wrote the sketch after a visit to Mayo and a consultation about my prostate. Real life fed the imagination, just like the Mississippi turned the wheels that ran the mills of Minneapolis. There was no agony involved, I just sat and wrote sketches, monologues, songs for the pleasure of it. E.g., the childish pleasure of rhyme:

Long distance information, give me South St. Paul,

Someone down at FedEx just gave me a call.

The wedding’s in an hour when she and I’ll be hitched.

It’s a package from my dentist, and it’s my lower bridge.

I bought her the big diamond and a fancy bridal wreath,

But I don’t think she’ll marry me if I don’t get my teeth.

I’ll be in the parking lot, so tell them, hurry please,

My car’s the one with tin cans and the windows smeared with cheese.

A simple story straight from me to you. So simple. Everyone else in public radio lived with the burden of high standards, shades of the BBC— the ambition to do investigative stories on the moisture of oysters farmed in Worcester. Not I. Parody was my beat, and my generation had a wealth of big shots to beat up on—Bob Dylan, for one.

May you grow up to be beautiful

And very rich and slim.

May God give you what you want

Though you don’t believe in Him.

May you stick your finger in the pie

And always find the plum

May you stay forever dumb.

And once, for a show at Bethel Bible College, we sang “Catch a Wave” (If you’re saved, you’ll be sitting on top of the world ). And a wedding sketch in which the bride sang (to the bridal march from Wagner’s Lohengrin: Why am I here? Who is this man? Why is he dressed up and holding my hand?) and the groom (Why does she cry? I wish she’d stop. I’m not bad looking and I have a job. I don’t smell bad. I am not gay. I’m in good shape and I floss twice a day.) and the minister (It’s not so bad. It could be worse. It’s better than coming to church in a hearse. Just say the words that must be said and then you can undress and go off to bed.).