21

Coast to Coast

IN MAY 1980, THE SHOW went coast-to-coast, uplinked live by satellite. Bill Kling had pushed for that and I was the defeatist—the show was local—but he said, “You’ll never know unless you try, and if you don’t try, you will someday wish you had.” So he pushed us out of our comfortable nest and he was right. New York turned out to be a hot spot for the show, along with Seattle, San Francisco, and Washington, DC, and big names were glad to come on the radio, the Everly Brothers, Renée Fleming, James Taylor, Marilyn Horne, Taj Mahal, Yo-Yo Ma, John Sebastian, just as Kling said they would. I grew up, as Minnesotans do, with a keen sense of inferiority, and Kling was a skier and said, “If you stay on the beginners’ slope, you’ll never get better.”

He’d campaigned for the national satellite system but public TV was in the driver’s seat, radio being considered an antique, like the Victrola. Public TV was riding high on the basis of BBC costume dramas and a puppet show called Sesame Street and a soft-spoken guy in a cardigan sweater named Mister Rogers. Parents could park their kids in front of the PBS screen and they’d never see violence except for sword duels. A retired Navy admiral was in charge of the satellite project, no mention of radio, until Bill Kling stepped in. He formed a consortium of radio stations that demanded thirteen regional uplinks rather than the one uplink that NPR wanted for itself in Washington. The admiral, after vigorously denying the need for radio, gave him a twenty-four-hour deadline to name the thirteen uplink sites, knowing that in public radio, due to the Eeyore tendency to form task forces to consider worst possible scenarios, decisions take years, not hours, but Mr. Kling promptly delivered the list of thirteen, one in St. Paul, and that put us in business. Mr. Kling was an entrepreneur who believed in the power of a good idea to win out over cliques and claques, inertia and neurosis, and he prevailed.

The show went up on the satellite May 3, 1980. Same show, staff of four plus the stage crew, now available to listeners in New York, LA, and all stops in between. I wrote the show. Same drill. Friday rehearsal. Extensive rewrites. Sound check on Saturday: once through each script, more rewrites, and then I jiggered the order of the show and typed it up and passed it around.

Tom Keith (and, later, Fred Newman) was the key to the kingdom of comic surrealism, which had never been my ambition but the audience loved it, a bloodhound reciting “To be or not to be, that is the question,” Bach played by a duck pecking a glockenspiel, that sort of thing. Writing prose fiction, I never came up to the high plateau of Thurber or Perelman or Charles Portis, but writing the show was child’s play. NPR was high-church solemnity, and we were the kids who saw the butt crack of the man knelt in prayer. The beauty of nonsense became clear: in our jittery times, with the winds of correctness blowing through public radio, playing to a crowd that was somewhat leftist and feministic and sensitive to stereotyping or biases or unfair generalizations, nonetheless the crowd liked to be teased and toyed with, as once, for Father’s Day, a poem with the lines:

Sperm beneath their shiny domes

Contain important chromosomes

And their tails can kick just like a leg.

O nothing could be fina

Than to swim up a vagina

In search of a rendezvous with an egg.

The laughter at the word “vagina” was gender-balanced, as many trebles as baritones, and so was the laughter at my limerick about the girl from St. Olaf, an Ole, who spread herself with guacamole and two theologians put on their Trojans and had her completely and wholly. The pun, “wholly” was not lost.

I’d loved limericks since the eighth grade, and now I had a reason to write more of them.

There was an old man of Nantucket

Who died. He just kicked the bucket.

And when he was dead

We found that instead

Of Nantucket he came from Barnstable.

The crowd got excited at “Nantucket” though they knew they shouldn’t, it was bad, and then “Barnstable” came along as pure innocence.

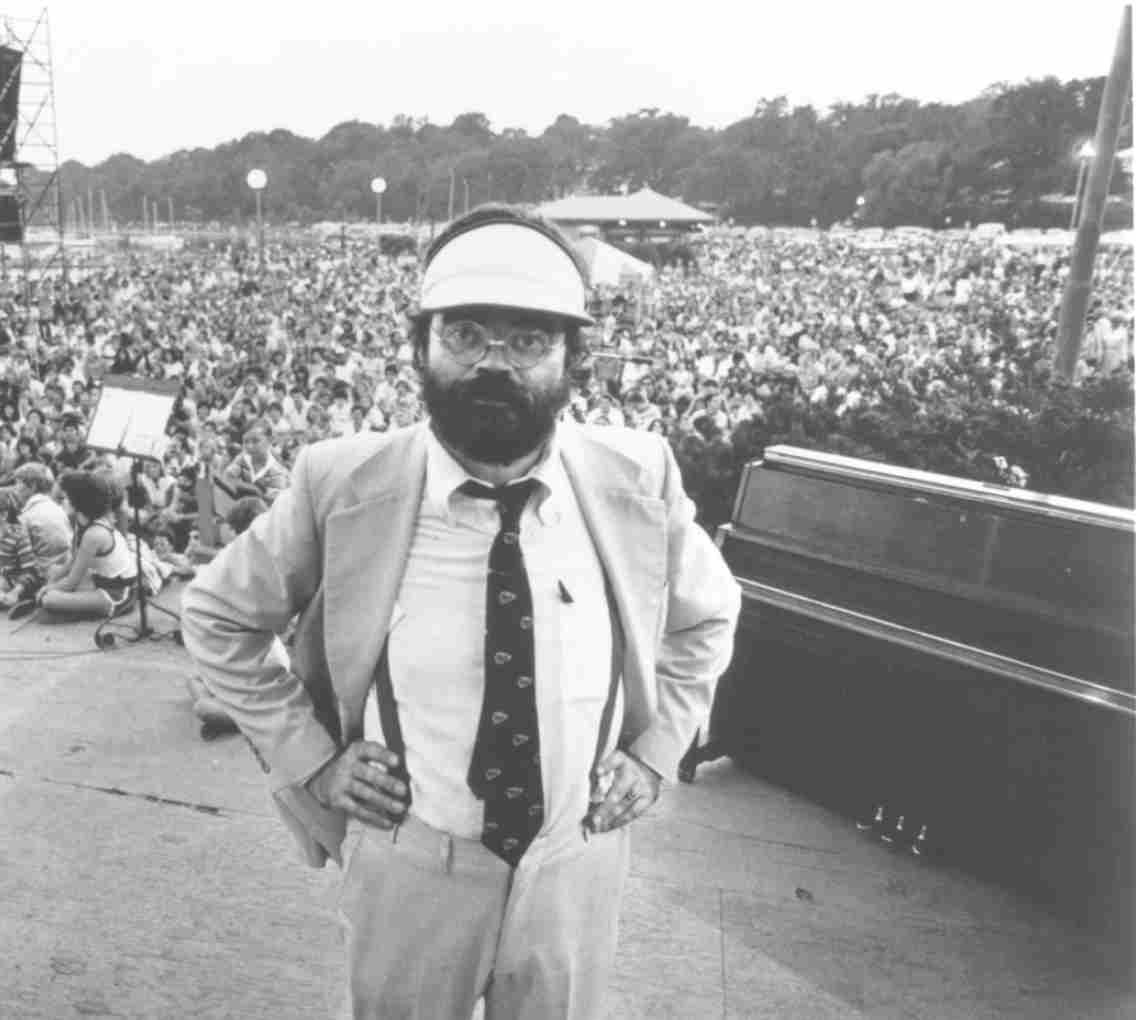

GK at Lake Harriet Band Shell show, August 4, 1979. A huge crowd, thanks to free admission and good weather. A first indication of Prairie Home’s appeal, and that is puzzlement on his face.

I was happy to tread the boards of low comedy on the air, just as Chaucer and Shakespeare had, but what I loved most about the show were the great singers who sat in a dressing room sipping tea and then came out on stage and sang from their heels and made the room levitate, singers like Hazel Dickens, Dave Van Ronk, Cathal McConnell, Aoife O’Donovan, Joel Grey, Renée Fleming, Jearlyn Steele, Soupy Schindler, Odetta. Each one singular, indelible, nobody else like them—between Hazel’s haunted, evangelical voice and Joel’s Yiddish patter song learned from his dad, Mickey Katz, and Jearlyn’s soul and Renée’s soul and Soupy’s R&B honk, each one carrying the full force of distinguished ancestry, a whole world on their shoulders. I loved them all. Soupy was master of the harmonica and the jug, sang in a blues growl, whooped and cried, and whatever he did, the audience wanted more, so I had to step on his applause. Soupy had the raw passionate voice I wished for myself: there was nothing soupy about it, it was all muscle, all heart. He’d grown up singing in synagogue in north Minneapolis, the son of Fanny and Julius, two Holocaust survivors, and he took up blues during a hitch in the Air Force, won everyone’s heart with his big personality. A Jew singing Black music, one oppressed people adopting another to make something beautiful out of pain. Soupy was funnier than I was and he could have taken over the show but for one thing: Soupy laughed hard at his own jokes. I never laughed at mine. In radio, cool trumps hot. Soupy’s spirit was strong, but he couldn’t earn a living in music and he worked as a men’s clothing salesman, drove cab, became a public schoolteacher, a fine one, and one day he dropped dead of a heart attack at 57. A great man in a difficult life.

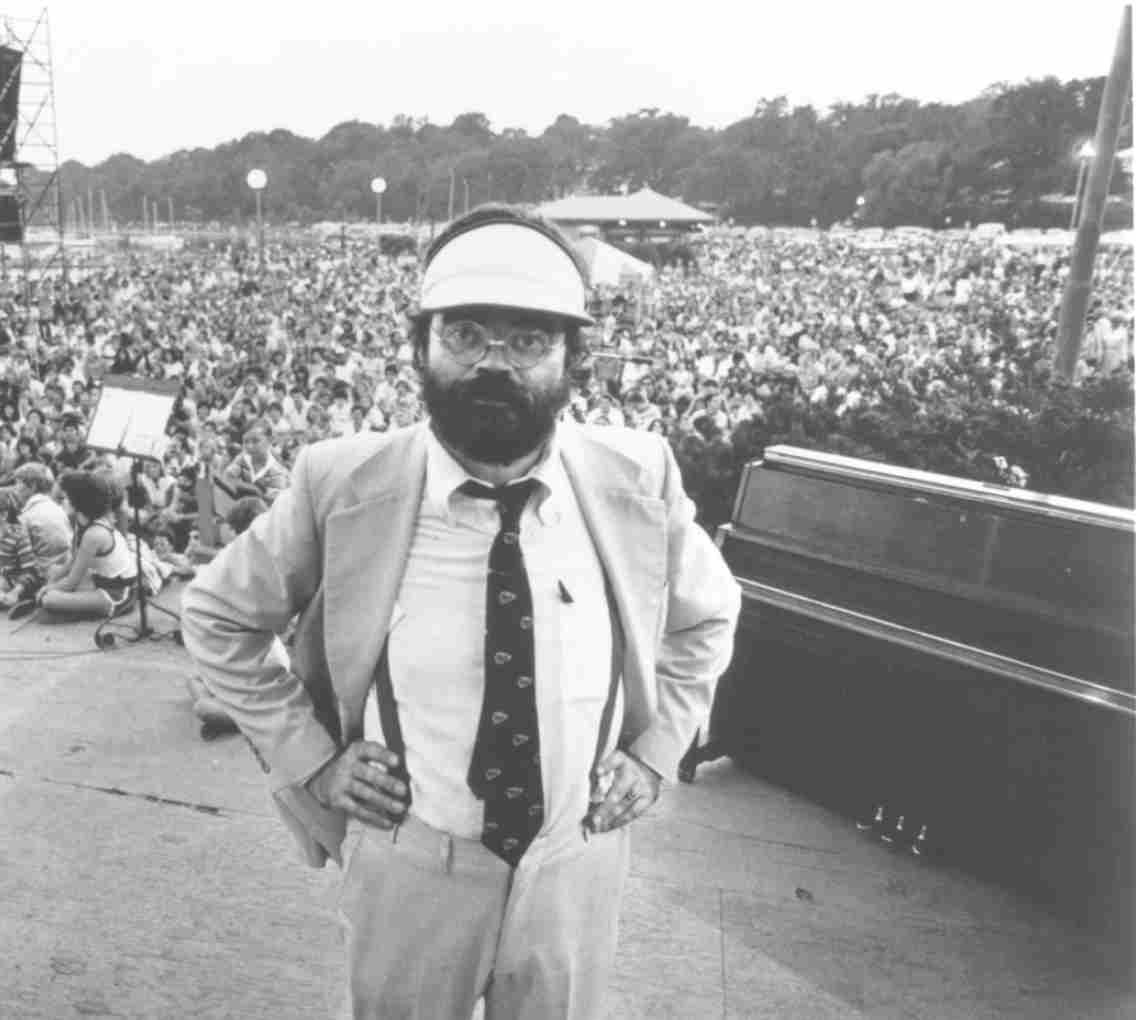

Soupy.

I was so engrossed in writing the show, I couldn’t see what a beautiful thing it was, a loose variety show with gallant musicians playing hot numbers interspersed with the comedy of loon calls and glass breakage and French double-talk, and a slow sweet story in the middle—a homely miracle but I couldn’t tell, I was too busy. We did good shows, the band shell at Lake Harriet and a ballfield on Nicollet Island, the Guthrie Theater, and in 1978 we rented the World Theater, an old rundown picture house whose owner, Bob Dworsky, was weighing a developer’s offer to tear it down and put up a McDonald’s. The World was a second-run theater, where if you had an afternoon to kill, you could sit in the dark and see the double feature for a couple bucks. Bob had four kids, a singer, a violinist, a drummer, and a pianist (Rich, who in due course, became our musical director), and in honor of his kids, Bob rented the place to us for $80/show. A gang of volunteers came in to scrape gum off the seats, and a crew of feminists whited out the “Ladies Toilet” sign in the lobby and painted “Women” over it. Our home. We renamed it the Fitzgerald in 1994.

In 1982, I boxed up a batch of stories (“Jack Schmidt, Arts Administrator,” “After a Fall,” “Don: The True Story of a Young Person,” “U.S. Still on Top, Says Rest of World”) to make my first book, Happy to Be Here, and thanks to the radio show it sold pretty well. I cut off my beard, an immense one that made me look like a man eating a sweater, and I did a publicity tour and as the book crept up the best-seller list, my accommodations upgraded from Holiday Inns to hotels with heated towel racks and rosemary-scented soap. At the end of the book tour, in Utah, I was put up in a private lodge at Sundance with high windows and views of snowy peaks and tall pines, where, alone on a chill March afternoon, I took off my clothes and went out to the hot tub and the door closed behind me and clicked. A solid click. It was locked. I had no key. Naked men often don’t. (Where would you put it?)

I sat in the tub, hoping a cleaning lady might drop in, or St. Jude, or a Saint Bernard, and when nobody did, I wrapped myself in a blue plastic tarp I took off the woodpile and trudged barefoot down the gravel road and knocked on the door of another lodge to ask for help. I learned that a naked man wrapped in blue plastic does not win friends easily. I knocked on the doors of five lodges with lights on and cars in the driveway and nobody showed their faces though I did see curtains move slightly. I waved in an urgent way to three men driving by in a pickup and their heads swiveled left and they drove on. The blue plastic was cold. My feet hurt from the sharp rocks. I considered dropping the tarp and being arrested for public indecency and getting warm in the back seat of a squad car. At the sixth house, a woman came to the door and opened it a crack. She agreed to call the resort office. She didn’t invite me in, so I walked back to the hot tub and was rescued an hour later by a security man, and that was the parable of the naked author in the blue plastic. Moral: A best-selling author is somebody and a naked best-selling author is nobody. You may be a big success, but be sure to put on pants.

GK at his Selectric in a rental apartment on Lincoln Avenue, St. Paul, 1981. A pack of smokes by the typewriter, old radio scripts on the floor. On the table behind, he’s assembling his collection, HAPPY TO BE HERE. Bachelor décor, a beer sign.

An old poet friend wrote to me: “My advice: work as little as you can for as much money as they’ll pay. Get the rent money and depend on your pen for the rest. Be a writer, not a comedian. The show is okay short-term but you have better things to do.” But he was wrong: I had found a vocation. My good intentions had found a road and a car to drive down it. The show was my education. Had The New Yorker hired me, I might’ve spent six years living in a basement in Brooklyn and trying to be E. B. White. Instead, I’d found an old abandoned house—the radio variety show—and put a new roof on it and moved in with my friends and made a house party every Saturday and learned to step up to the microphone and talk to the people. I learned to write compact sketches that delivered jokes, do a meandering monologue about minor issues, and as a reward for good service I got to sing a duet now and then, but mostly I talked. After Jearlyn and Jevetta Steele came juking onstage to do “R-E-S-P-E-C-T,” my story about Clarence and Arlene Bunsen’s miserable Florida vacation fit very nicely, like after the high-wire act it’s nice to bring out the man who juggles cats. It was not hard labor. Any third-grade teacher worked harder than I. Once a week, two hours at 5 p.m. Central, a lazy man’s dream.

With the proceeds from Happy to Be Here, I went to Murray’s and ordered the Silver Butter Knife Steak, and then I bought a big frame house on the corner of Goodrich and Dale in St. Paul, a hospitable house with four bedrooms, a fenced-in backyard, a commodious screened porch in front. Guests moved in when they played the show and stayed, sometimes for a week—Jean Redpath was a perfect houseguest and could remain for two or three weeks, no problem. Cereal and fruit were set out in the morning, the coffee was on. Help yourself to the refrigerator. She stayed in her room and wrote letters and read, and every day she sang for a half hour or so, songs in Scottish Gaelic that maybe she wouldn’t have sung to an American audience but my God they were magnificent—her voice came down the back stairway and I listened. In the evening, we met for a meal and I never told her how I admired her singing for fear she might prefer privacy.

Robin and Linda Williams were regular houseguests and Kate MacKenzie came over one day and we formed the Hopeful Gospel Quartet. We sat in the garden behind the board fence and sang, Come thou fount of every blessing, tune my heart to sing thy praise, and Sheep, sheep, don’t you know the road—yes, Lord, I know the road and when Jean Red-path heard us in the yard, she came down to join us, her Scots soprano filling out, You’re drifting too far from the shore and He may not come when you want Him but He’s right on time. I sang bass. Finally I was a member of a band, a big jump in status from hostship. Gospel music was unknown on public radio, except in a documentary about the civil rights movement or an Aaron Copland arrangement, but I’d grown up with it and loved the sonorities: the descending bass part on “Now the Day Is Over,” singing, Shadows of the evening steal across the sky. We sang “Softly and Tenderly Jesus Is Calling” and sensed that, for most of our audience, songs of repentance were not what they’d come to hear, but what the hell, a little guilt never hurt anybody. And our “Calling My Children Home” actually made people cry, especially parents of teenagers: I’m lonesome for my precious children, they live so far away. Oh may they hear my calling— calling—and come back home someday. We did a couple of national tours and even played Carnegie Hall, and we sang my dad’s favorite poem, Twilight and evening bell, and after that the dark! And may there be no sadness of farewell when I embark. Helen Schneyer was another houseguest who joined us in singing, she of the flowing white dresses and pounds of turquoise jewelry on fingers and wrists and hair and neck, singing spirituals and ballads about mining disasters in her rich baritone, playing gospel stride piano. Hazel Dickens sat in the living room and sang “West Virginia”—In the dead of the night, in the still and the quiet I slip away like a bird in flight. Back to those hills, the place that I call home.—her voice, rough and tender, a country voice of someone who’s handled horses and beheaded chickens. I loved the powerful singing of mature women, and it was satisfying to find out that others loved it too. Our producer, Margaret Moos, took a big chance and booked the enormous Orpheum in downtown Minneapolis for a Big Lady weekend––Jean and Helen and Lisa Neustadt—and sold out three shows. When the three of them sang, “Dwelling in Beulah Land” or “Palms of Victory,” it was Baptist revival time, the crowd standing to shout the choruses, led by two Jewish ladies and an agnostic Scot. Truly God works in mysterious ways His wonders to perform.

The Hopeful Gospel Quartet, Robin, Linda, Kate, GK.

I loved my house on Goodrich and wish I had held on to it. Minnie Pearl came up from Nashville with her husband, Henry Cannon, and did her act on the show (Brother went in and applied for a job and the man said, “We can start you at thirty dollars a week and in five years you can be earning five hundred.” And Brother, he says, “I’ll be back in five years.” ) and she sat on that front porch with a bunch of us and reminisced about her friend Hank Williams, the saddest man she ever knew, drunk, dosed with morphine, dead at 29 in the back seat of a car heading for Canton, Ohio, and she recalled when Red Foley sang “Old Shep” and then introduced his guitarist Mr. Chester Atkins, who played “Maggie,” and afterward Minnie walked up and kissed him and said, “You’re a wonderful musician, you’re just what we’ve been needing around here.” Her face shone as she told stories. She was a shining presence. Comedy was only part of it: she loved people with her whole heart, and that was the heart of her act—she was the happiest person on stage that you ever saw in your life, and she told those jokes so well you almost forgot how old they were, and nobody ever looked at you with so much joy as Minnie did, except maybe your grandma if you were lucky.

Miss Jean Redpath.

Chet Atkins walked into the picture around 1983, and that pretty much brought the Amateur Hour Era to an end. After the friends and neighbors have heard Chet Atkins, they’re no longer content to hear “Go Tell Aunt Rhody” strummed on a dulcimer, the bar has been raised.

Chet called Margaret Moos and said he was a fan of the show and would be happy to come up north and play on it sometime. He was the most famous guitarist in the world, a soft-spoken, stoop-shouldered gentleman in a pale green sport coat and tan pants who walked into the theater one Friday afternoon and set his guitar case down and shook my hand. He said he admired the show. He had no entourage, just him and his wife, Leona, and his sideman, Paul Yandell. We sat backstage and talked. He was a real storyteller. He grew up dirt poor in a broken family in east Tennessee, suffering from asthma, painfully shy, and he made himself a banjo with strings pulled from a screen door. Got a Sears Silvertone guitar and played it morning and night, trying to sound like Les Paul and Merle Travis and Django Reinhardt, whom he heard on the radio. He knew that if you could play guitar as they did, you would join a natural aristocracy of artists in which white or Black, Southern or Northern, shy or charming were accepted equally. Anybody with an ounce of taste would respect you for it, and to hell with the others.

Mr. Chester Atkins, (CGP) Certified Guitar Player.

Every time Chet came on the show, he’d sit backstage and jam with Paul and whoever wanted to join in, Johnny Gimble, Bill Hinkley, Howard Levy with a harmonica, Peter Ostroushko, and the tunes would flow along from old-time to swing, one tune emerging into another, “Just as I Am” into “Stardust,” Stephen Foster, George Harrison, “Seeing Nellie Home,” “Banks of the Ohio,” and maybe Recuerdos de la Alhambra, Boudleaux Bryant, “Freight Train,” one sparkling stream, it was all music to him. He held his guitar like a father holds a child, he was happy, the genuine article. He loved jamming backstage, where he wasn’t obligated to be Chet Atkins and could be a man in a crowd of friends. He had made his way in the country music business though his real love was jazz, and when he sat backstage with the others, a sweet equality prevailed in which strangers were old friends—the music made it so. I envied that and asked Chet once if I should learn to play guitar and he said, “The world does not need another mediocre guitarist. Stick with the monologue. Nobody else does what you do.” So I did.

Chet gave me good advice: “Never read anything anybody writes about you. No matter what they write, you won’t learn anything from it, and you’ll probably read something that’ll be a stone in your shoe for months to come.” I could see the reasoning, which was the same as what LaVona Person told me in the eighth grade: It’s not about you. It’s about the material. Don’t make it be about you.

My front porch looked across Goodrich at the house Scott and Zelda lived in when he wrote “Winter Dreams,” after they returned briefly to St. Paul in 1921 for the birth of their daughter. His parents’ row house, where he wrote This Side of Paradise when he was 24 and broke, is a few blocks away on Summit, and Mrs. Porterfield’s boardinghouse porch where he sat with his friends and talked about the great life he would live. He was a romantic. His parents, Mollie and Edward, had lost two little girls to influenza the year before he was born, and so the boy’s feet were not allowed to touch the ground. He grew up believing the world would smile on him. He had little fondness for St. Paul: his city was New York, and he and Zelda left town after a few months and never returned.

I started to get a whiff of success now and then myself. I’d walk to the drugstore on Grand and someone’d stop me and say they liked the story about the Gospel Birds or the one about the truck stop. They didn’t gush, they just mentioned it like you’d say, “I like your shirt.”

Success felt precarious. Around the corner on Lincoln Avenue was the little walk-up apartment where I’d lived before, a daily reminder of what might befall me if I should take up bad habits and go fallow. I worked hard to avoid that. I sat in the garden by the high board fence, drank my coffee, smoked, scribbled on a yellow legal pad, writing epic verse for the shows––“Cat, You Better Come Home” and “The Old Man Who Loved Cheese.” And “Casey at the Bat” from the perspective of the opposing fans overjoyed at his downfall:

Ten thousand people booed him when he stepped into the box, And they made a vulgar sound when he bent to fix his socks. He knocked the dirt from off his spikes, reached down and eased his pants— “What’s the matter? Did ya lose ’em?” cried a lady in the stands.

I’d given up my 6 a.m. daily show, but I arose in the dark and went to work, writing, a pack of Pall Malls nearby, and in February 1982, tired of worrying about it, I quit smoking. I was a three-pack-a-day man and Butch Thompson and I made a compact that we’d phone the other before lighting another cigarette, and that slight social pressure, the reluctance to admit defeat, did the trick. Smoking and writing were inextricably linked, and I spent about three days in the public library and other No Smoking zones and ate buckets of popcorn, and then I was done with it, the inextricable was extricated, a long-running comfort gone, no regrets, a knapsack of rocks lifted from my shoulder. It simply needed to be done.

The show was doing well, though I was oblivious. One day, the station’s music director, Michael Barone, walked up to me at a staff lunch and thanked me for bringing so much money into the operation. And I was surprised to learn that PHC was in the black. Way in. I did not think to ask for a raise, but Bill Kling gave me one anyway. Around 1982, the show had taken a mercantile turn—Powdermilk Biscuit posters, LPs, the four-cassette “butter box” of Lake Wobegon monologues sold enough units to start a new catalog company.

And then another phenomenon, very charming and also bewildering: I noticed women taking an interest in me. Normally this should happen around the age of fifteen, not in your forties, but the road life and the warmth of audiences loosened me up, the beard came off, maybe I switched to a deodorant with aloe and rosemary in it, and I started to encounter women who made it clear they enjoyed my company and wished to spend some time in it. This was an astonishment. I was tall, not bad looking, sort of professorial but not overbearing, and they made their feelings clear, standing close, speaking low, placing a hand on the small of my back, laughing at what I said, maybe their forehead to my shoulder—women have ways to indicate interest. The first time was at a party after a Valentine’s Day show. A woman took me in hand and danced me around, though I’m not a dancer. None of the girls at Anoka High School had done this, so I was grateful. We stood outside in the yard and kissed with some conviction and she asked if I’d like to continue the evening at her apartment. I said, “I’m a little drunk,” and she said, “We’ll just make the best love we can.” So we did.

I met a woman at a party who asked me to sing Everly Brothers songs with her and we did “Devoted to You” and “All I Have to Do Is Dream”—she sang lead, I sang harmony, and our voices fit well together and later so did we. It was a beautiful romance and she wanted to marry, but I was afraid of disappointing her and then I was unfaithful to her with another romance and we parted, sweetly, and I was happy when she found a good husband. They were Lutherans and made love at least once a week, as Luther recommended, which I was glad to know. A man wants his old lover to be loved well.

There was an old classmate who flirted with me and we became lovers and then gracefully eased back into friendship where we were content to remain. This struck me as so civilized, friendship turning passionate and then returning to kindness and attentiveness. It was a series of pleasant fantasies, to not go looking for love but see love come looking for me. I had gone into radio for purer, finer reasons, but I did not mind being suddenly attractive to women. I’d been the nerd holed up in the library scribbling in a notebook: women glanced at me and kept walking. Radio made me appealing somehow.

One day I flew out to Santa Barbara to do a show and afterward went around the corner to a café. I’d found a note in the dressing room when I arrived:

Mr. Keillor,

I am coming to your reading tonight because I find your stories ridiculously delightful and if you feel like having company afterward, I will be in the café on the corner. I’ve never done this before, I swear to God, but it would rock my world to meet you.

Cheers,

Marty (Martha)

She was 21, tall, lean, a grad student. We ate chicken quesadillas and had a beer and afterward we sat in my rental car in the parking lot and I asked, “What do you want from life?” She said, “Adventure.” She asked what I wanted and I said, “Impetuosity. Courage.” “To do what?” she said. “To kiss you.”

She smiled and looked away. “I’d play hard to get but I’m leaving on a peace mission to Bolivia in two weeks.” And we kissed. She said, “Where can we go to be alone?” I drove us to my hotel. I turned on the gas fireplace. We sat on the couch, kissing. We went into the bedroom. I pulled the sheet up over us. It was all so easy. We made love and lay together for a while. She said, “Either I am going to go home now or I am going to stay the night.” I said nothing. She arose and got dressed. I kissed her goodbye.

It was stunning a woman had gone out of her way to seduce me—and not a crazy woman but a smart one, off on a mission to South America.

She wrote to me a week later:

Our evening together was wonderful and for me very much an indulging of fantasy and part of me wishes there would be more but I’ve talked to a trusted friend about this and she says, “Leave it at one night. Don’t be fascinated by celebrity. Too complicated.” So that is the way it shall be. But I love you and want all the best for you. Marty

I didn’t think of myself as “celebrity”—I’m from Anoka, Minnesota. But she had come upstairs with me because she liked my show and I enjoyed being seduced. I am not a strong man, my ego is made of butterscotch pudding, to think that admiration of my writing makes a woman want to take her clothes off strikes me as irresistible. She found a good husband and they started a family and every five years or so she drops me a line. I am an episode in her wild youth. When she is old, if she thinks of me, she’ll shake her head and laugh.

After Happy to Be Here, I sat in my big house and worked on a Lake Wobegon book. No plot, no crisis to resolve, a set of merged stories arranged by seasons for a semblance of structure. With some history of Lake Wobegon, the early Unitarian missionaries who sought to convert the Dakotah through interpretive dance, the immigrants who settled here because the land reminded them of home, forgetting they had left home because the land was so poor. As I worked, I thought about the draft board order I’d ignored sixteen years before, imagined the FBI at the door, the book rejected, the show canceled, a rented room over Gray’s Drug in Dinkytown, a job in a parking lot, sitting in Al’s Breakfast, a sad old man of forty. “I used to be on the radio on Saturday night,” I’d say to Crazy Phil, and he says, “I know, I was your biggest fan.”

No such luck. My editor at Viking, Kathryn Court, came out for a week and then another week to work on the book I was patching together, trying to make a novel out of a set of stories. She was crisp and British and set up shop on the dining room table and we glued pages and paragraphs together into chapters and hung them on the walls in long yellow banners. Somehow, she believed that Lake Wobegon Days might be a big seller so I kept rewriting it, revising the rewrite, editing the re-rewritten, repairing the edits. If so many people were going to read it, I wanted my book to be good enough. My girlfriend at the time resented this intrusion and sniped at it and said it was a big mistake. She’d never lived with a writer who was engrossed in making a book. I forgot to watch TV and never went out at night. I wrote some for The New Yorker, wrote the show, worked on the book. I could feel it coming along.

I shipped the manuscript off to New York and the girlfriend and I broke up in the spring. She said that I couldn’t get along without her. There was only one way to find out. As it turned out, I could.

Work, not domesticity, was what kept me on an even keel. I woke up in the morning and worked. Sometimes I woke up in the middle of the night and got out of bed and wrote things down. Work was therapeutic: I talked to a shrink once because I felt depressed, and she was very nice, but I needed to write myself out of depression, which made me feel good and sometimes produced good work that maybe even earned money, so why pay her?

The girlfriend disappeared in May 1985. Lake Wobegon Days came out in August, and the Times Book Review printed a front-page review of it by Veronica Geng, ranking it alongside Thurber and Lardner, setting my (small) marble bust on the shelf alongside the masters. I should’ve written her a thank-you note and did not lest I be thought a greenhorn, and the book shot up to No. 1 on the Times list and stuck there. It was hard to look my writer friends in the eye that year. A journeyman novel sold by the carload, while masters and innovators went scarcely noticed. If you’d written a novel about someone like me, a Brethren Boy, suddenly become Mr. Wonderful, it’d be turned down and sent back, Sorry, better luck next time.

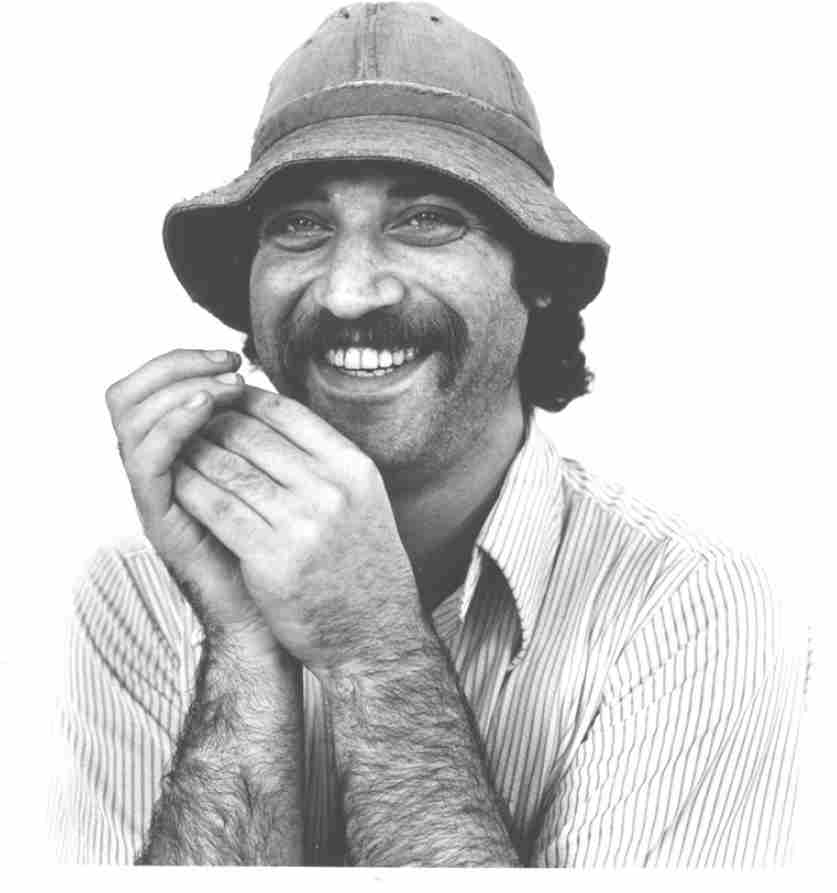

A published author, feeling good about himself. One book out, another on the way, the beard is gone, he’s quit smoking, and for the first time in his life, certain women seem to take an interest in him. But still a nerd at heart, and still wearing the work boots he wore in college.

For years, I had looked down on best-selling books and then one of them was mine and it turned me upside down on a roller coaster of confusion. In hindsight, I see I should’ve stayed home, locked the doors, turned off the phone, stuck to business, and not strayed from the sensible and self-sufficient, but looking back, I see that that would’ve made for a much less interesting memoir.