25

Friendship and Fame

THE DOTY HOUSE ON PORTLAND and the big white manse on Summit, the houses Maia grew up in, were a couple blocks from my pal Patricia Hampl, a St. Paulite born and bred, raised by the nuns, and she’d written genius memoirs about the neighborhood, A Romantic Education and The Florist’s Daughter, and owned it literarily. I was Protestant, a visitor. Back in college days I used to walk the streets that Fitzgerald had walked and look at the old Commodore Hotel where he had a few drinks and his parents’ row house where he finished writing This Side of Paradise and where he ran out into Summit Avenue and stopped cars to tell people that Scribner had accepted it for publication. Down the street was the Empire Builder James J. Hill’s enormous stone castle, looking like a Victorian train station or an insane asylum, take your pick. Mr. Hill built a railroad and is also known for having died from an infected hemorrhoid. Across the street, Archbishop Ireland’s cathedral designed by the French architect Masqueray, whom the archbishop worked to death building majestic edifices, fifteen of them. He died of a stroke at age 56 while riding a streetcar down Selby Avenue and was carried off and laid on the grass and died looking up at the cathedral dome. Downtown is Wabasha Street, named for the Mdewakanton Dakota chief who ceded all this land to white men in 1837, adopted Western dress, became Episcopalian, supported the government during the Dakota Uprising of 1862, did his best to knuckle under, and for his loyalty the government shipped him in iron shackles to Nebraska along with his people, where he died and was buried in a little grove of trees on the open prairie. Down the hill is Kellogg Boulevard, named for Frank B. Kellogg, a St. Paul lawyer and Calvin Coolidge’s Secretary of State, who negotiated a treaty, signed in Paris by all the major powers, men in morning coats and top hats, renouncing warfare as a means of settling disputes, which won him the Nobel Peace Prize, after which Kellogg retired to a big house on the hill and watched the world fall apart: Japan invaded Manchuria, Italy invaded Ethiopia, Russia invaded Finland, and Hitler invaded Poland. Kellogg would’ve contributed more to the world had he invented Grape-Nuts. He intended to be a savior and instead he became a boulevard.

Frank Kellogg drew up a pact

Outlawing war—that’s a fact.

It was quickly signed

By the deaf and the blind,

And the powerful promptly attacked.

And then there was Fitzgerald, who said, “Show me a hero and I’ll write you a tragedy.” He was thinking of himself, as he generally did. He didn’t like St. Paul, so he left in his twenties and never returned. He was a literary sensation at the age of 24, the Handsome Schoolboy of the Jazz Age, and wound up burned out at 44, an invalid in Hollywood, worrying about his daughter at Vassar, in debt to his agent, watching his old pal Hemingway coming out with For Whom the Bell Tolls as Fitzgerald wrote stories about a hack writer, based on himself, and a few days before Christmas, he jumped up from his chair and fell down dead from a coronary.

It’s a neighborhood of cautionary tales about the perils of prominence, nonetheless I persevered, since I was enjoying myself. Fame is a role and some people play it very well, such as George Plimpton, who crashed a party at my apartment in New York one night. I hadn’t invited him because I didn’t know him, he was too famous for me to know, but he wanted to be friends so he came around midnight and sat at the dining room table, jiggling a glass of Scotch and holding court, talking about Hemingway at the Café de Tournon and the bar at the Ritz and E. M. Forster whom he interviewed for the Paris Review and Ezra Pound. George invited me to lunch at the New York Racquet Club and showed me the tennis court modeled after the one Henry the Eighth played on, an actual courtyard with walls and a roof to play the ball off. He explained the arcane rules of court tennis and took me down to the library where we sat in leather chairs and he told about the book he’d found in which an Old Member had hidden his correspondence with his mistress, describing her breasts as “gleaming rosy-tipped orbs.” My Midwestern bias against clubbiness runs deep, but George was a real writer, his Paper Lion and Out of My League part of the literature of sports. And his great adventure was founding the Paris Review in Paris when he was 26 years old, living in a toolshed, sleeping on an army cot, dropping in at the Hôtel Plaza Athénée to write letters on hotel stationery to his parents assuring them that he was having a fine time and wasn’t ready to get a job on Wall Street yet. He remained 26 on into his seventies. He was a tireless encourager, and generosity, not cleanliness, is what is next to godliness. That night at my apartment, he left around 4 a.m. “I miss staying up all night,” he said. “That gray light in the morning. You think your time is up and then you get a second wind.” We stood out on Columbus Avenue, cabs passing by. He said, “I envy you getting to talk to all those people on the radio. People hear my voice and they get their backs up, they hear Harvard snob. I tell you, friendship is what it’s all about. It’s all it’s ever been about. All my deepest regrets are about people I missed my chance to get to know, and it’s always for the dumbest reasons.” And then a cab stopped and he got in, waved, and was gone.

Friendship is what it’s all about, all it’s ever been about. I think of my disapproving father whom I never knew and how happy he was with his sister Eleanor. He never was at ease with Mother’s family; with Eleanor, he was completely happy. I sat in the next room and listened to them, talking and laughing, he was someone I didn’t recognize at all. I was in the business of impersonating friendship on the radio, and one day I got a friendly letter from Maggie Forbes, my Latin teacher at the U, for whom I wrote clumsy translations of Horace, who wrote from Texas to say she loved the show, and I stared at her letter in happy disbelief. The woman had seen a dense dull side of me and now we were friends. My doorbell on Portland Avenue dinged one morning and there was Charles Faust, my old history teacher and now he wanted to be friends. Helen Story came to a party at my house and said she admired Pontoon and admired Love Me even more. She was on her way to the Stratford Festival, flying to New York and London, planning a trip to Machu Picchu, not a word about her years of servitude at Anoka High, only about her love of theater. LaVona Person asked me to speak at her retirement dinner; she was proud of having been my teacher—this thrilled me more than any prize could, that I’d won the regard of the woman who showed me that if I took off my glasses, the audience became a Renoir hillside.

I acquired a friendship with the writer Carol Bly, who wrote me weekly about her anger at oppressive Lutheranism and the need for boldness and honesty in all things artistic and the need for comedy that doesn’t jeer at people but facilitates self-confidence and psychological growth, and why, instead of teaching critical reading in English classes, they should require kids to memorize stories from age seven on up through college, so you can tell Moby-Dick to someone or Lord Jim or David Copperfield—she kept trying to enlist me in good causes to open all systems wide and let the sun shine in. When she read that I was going to speak at the dinner of the White House Correspondents Association and the Clintons would be there, Carol badgered me to not tell jokes but call the administration to battle.

I wrote a funny speech and went to the dinner and sat next to Mrs. Clinton, who was good to talk with. I’d just attended a Supreme Court session, and I talked about how inspiring it was to see them at work and suggested she visit sometime. She laughed and said, “I don’t think it’d be a good idea for me to show up in a courtroom where a member of my family might be a defendant.” It was the year before the impeachment of her husband. And then she turned and bestowed her attention on the old Republican bull sitting on the other side of her, Speaker Dennis Hastert, whom nobody was talking to. It was her duty to be civil to him, not to amuse me, and she focused on him and even made him chuckle a few times, no easy task.

Out of nowhere came a friendship with the jurist Harry Blackmun. It was his idea, not mine. I don’t aspire to be on a first-name basis with the US Supreme Court, but Harry grew up on Dayton’s Bluff in St. Paul, a blue-collar Republican, and he listened to the show regularly, or so he said. We wrote back and forth. I met him years later at the Court and we took a walk around the block, he in a blue cardigan frayed at the sleeves, an old blue raincoat, and, coming back, he stopped to listen to the picketers on the Court plaza, protesting the decision he wrote in Roe v. Wade that struck down state restrictions of abortion. They paid no attention to me or the slight bespectacled gray-haired man next to me. He said, “Maybe they take you for my security,” but it was his own humility that shielded him. “They still write me a lot of letters,” he said, “and I try to read them.” Then he walked up the steps under the Equal Justice Under Law inscription and went in to his office where he kept, in a frame, a chunk of his apartment wall with a bullet hole in it where some anonymous sniper had fired at him and missed. He was still miffed at the insurance company that did not fully compensate him for the upholstered chair that the bullet had passed through.

I sang at his funeral a few years later. His daughter Nancy had asked for the two songs he’d sung to his girls when they were little and he came home late from a long day at work and found them already in bed, the “Whiffenpoof Song” and “Toora-loora-loora,” so I did those at the church. It was a big Methodist church, downtown Washington, and his colleagues were there in their black robes, sequestered in a library with two glass walls, to protect them from fawning. I’d seen them in session, on a high dais in their magnificent Cass Gilbert courtroom, like the Nine Grand Masters of the Ancient Order of Woodmen, hearing candidates for apprenticeship, and now they trooped into the sanctuary and sat in the front pew. When the minister nodded to me, I walked up front and said that at the family’s request we were going to sing the lullabies Harry sang to his girls when they were little and launched into “Toora-loora-loora,” and the congregation joined in but not one of the Justices. Not even the liberals would so much as move their lips. (Had they taken a vote on this? Had they examined the text and found a loora that was inconsistent? Or lurid?) President and Mrs. Clinton sang, and so did Al Gore and numerous senators, Bill singing with a big grin:

We will serenade our Louie while heart and voice shall last

Then we’ll pass and be forgotten with the rest.

Maybe it was the “We are little black sheep who have gone astray, Baa-baa-baa” that made the Justices uneasy, fearing it would undermine their authority, but they sat mute, unmoved, resolute bad behavior in a crowd of singers. I thought about it all the way back to the train station. A hardworking jurist loved his little girls and wanted to have a few sweet minutes with them at the end of a long day. He’d stayed late at the office doing his duty, untangling the deliberate obfuscations of highly paid attorneys, and now he allowed himself to sing Toora-loora-loora toora-loora-li to his little Whiffenpoofs in recognition of his true purpose in life. Bill Clinton got that and sang, and the judiciary declined. A court that cannot comprehend a father’s love is weak on fundamentals, I say. Lord have mercy.

One night in New York, a guy in an NY baseball cap sidled up to me on 86th Street where I was waiting for the light to change and he said, “The writing on the show has been really good lately.” It was a very famous comedian, I forget his name but I knew it at the time and so did everyone else in America. This is a beauty of fame, the ability to bestow a blessing. I once sat in the NBC Green Room waiting to go on the Letter-man show and suddenly Al Franken was there, leaning down, to give me good advice. He said, “Just remember: this isn’t a conversation, it’s a performance, you can’t go out there and just sit back and get comfortable.” Of course, that’s exactly what I went out and did. Dave said, “So what’ve you been up to lately?” cueing me for a routine, which I hadn’t worked up, and I said, “Oh, not much. How about you?” I died a slow death. But Al had given me his blessing. He’s from Minnesota, some of his best friends are Protestants, he knows our problem: we do not want to be seen trying too hard to look good. We prefer to be casually offhandedly humorous, not determinedly funny.

I went to the 1996 Grammys in New York, expecting to win one for my recording of Huckleberry Finn, and I saw heavy security at the Garden and heard police helicopters and realized that Hillary Clinton was in attendance and the fix was in. The First Lady had not come all this way just to watch me accept the Spoken Word trophy. Mark Twain had lost to her warmed-over Unitarian sermonette on interdependence, It Takes a Village. So I turned around and got back on the C train and she got the prize and rode to the airport in a motorcade that tied up traffic for a couple hours. Huck Finn was a better piece of work but I’d already won a Grammy in 1987 for Lake Wobegon Days, which I listened to a few days later and decided was a phoned-in job. So you win with a piece of crap, you lose with a masterpiece. Anyway the subway is a better place for a writer than a motorcade, and when you’re wearing a tuxedo, as I was, you’re a person of interest. Your fellow passengers take long looks at you and see no instrument case so you must be a waiter but why is a waiter on the uptown train at 8 p.m., was he fired? But he’s so unperturbed. And then they get it: he quit, he was insulted and walked off the job. And you stand up at your stop and there is silent applause in the air. I felt admirable. A waiter who refuses to accept insult is the equal of a Grammy nominee. I’d been nominated sixteen times and so what? The real prize was the line in the dark from the famous guy in the NY cap.

The radio show was on cable TV for a while and I was camera-shy like my grandma—in every snapshot of her she looks irked, and so did I on TV. Self-deprecation is the Midwestern default mode. On the screen I look like somebody’s brother-in-law looking for his car keys. The TV director didn’t dare direct me but Jenny told me a dozen times: Do not turn your back on the audience. Do not try to be inconspicuous. It doesn’t look good. But I kept turning my back. In the act of concentration, talking or singing, I’d wheel around, stare at the floor, wander down to Dworsky at the piano, stare into the wings, the host of the show trying to avoid drawing attention to himself, which was absurd.

I was slightly famous in a transitory off-center way, but I saw the real thing back in 1989 when I had a small part in a 100th birthday salute to Irving Berlin at Carnegie Hall. He wasn’t there, but everyone else was. It was the Show Biz Hall of Fame, but the statues were living, breathing people. I shook hands backstage with Tony Bennett, Rosemary Clooney, Marilyn Horne, Shirley MacLaine, Willie Nelson, and Ray Charles, who reached for my hand before I could get up the nerve to reach for his. Tommy Tune walked over in tap shoes before his big number, “Puttin’ on the Ritz.” Walter Cronkite was there and a rather low-key Bob Hope. Isaac Stern. Joe Williams. One household name after another and also me. I got to see Leonard Bernstein walk up to Frank Sinatra and say hello, two men whose like will never be seen again. Bernstein wore a boa and was all bonhomie. Sinatra seemed uneasy. Bernstein said, “Love your stuff.” Sinatra sang “Always” on the show and muffed a few notes and the stage manager had to walk out onstage and say, “Mr. Sinatra, one camera was out of position, the director would like you to do it again.” Mr. Sinatra said, “Of course.” It was very comfortable. They were all phenomenally famous and very good at playing themselves. I was the walk-on. I got to stand on stage and recite “What’ll I Do?” as a poem, all eighty-eight words. From memory. It was good enough. But I could not bring myself to walk up to the gods and make small talk. Frank Sinatra— my one chance to say hello to Frank Sinatra and admire the toupee and the tan, and in the interest of being cool, I stood off to the side with my hands in my pockets and looked at the wall above his head, pretending to be unamazed.

The people at the Berlin tribute were world-famous. I was famous in downtown St Paul. I walked up Wabasha Street to Candyland for buttered popcorn one day and was stopped by a grizzled old guy who said, “You’re Garrison Keillor, aren’t you? I haven’t read your books, but I saw your picture in the paper. How about a few bucks for an old bum down on his luck?” And I reached into my pocket and pulled out a twenty. I handed it over. “You wouldn’t happen to have another one of those, would you? It’d sure help me out.” I gave him another. I felt that I was buying good luck. I wished him well and he walked away.

To me, fame was like having a bright pink convertible parked in your driveway that isn’t yours but people think it is. I enjoyed the silliness of it. One fall, the Minnesota North Stars invited me to drop the first puck and open their hockey season. I asked John Mariucci, a Stars exec, why I was chosen, and he put his hand on the back of my neck and squeezed it. “We’ve had our eye on you,” he said in his Lucky Luciano voice. “We’ve seen you drop quite a few things over the years, and we like your style. You have a good release.” So I went shuffle-sliding out to mid-ice, the two opposing centers posed, I dropped the puck, they feinted toward it, we shook hands, I shuffled off. A moment of public meaninglessness, but a pleasure still, and I got to keep the puck and stay for the whole game.

I used my platform to honor my heroes. I had the power to do it so I did. Roger Miller came on the show, Wynton Marsalis, the jazz violinist Svend Asmussen, Victor Borge, Jim Jordan who played “Fibber McGee,” the great Paula Poundstone.

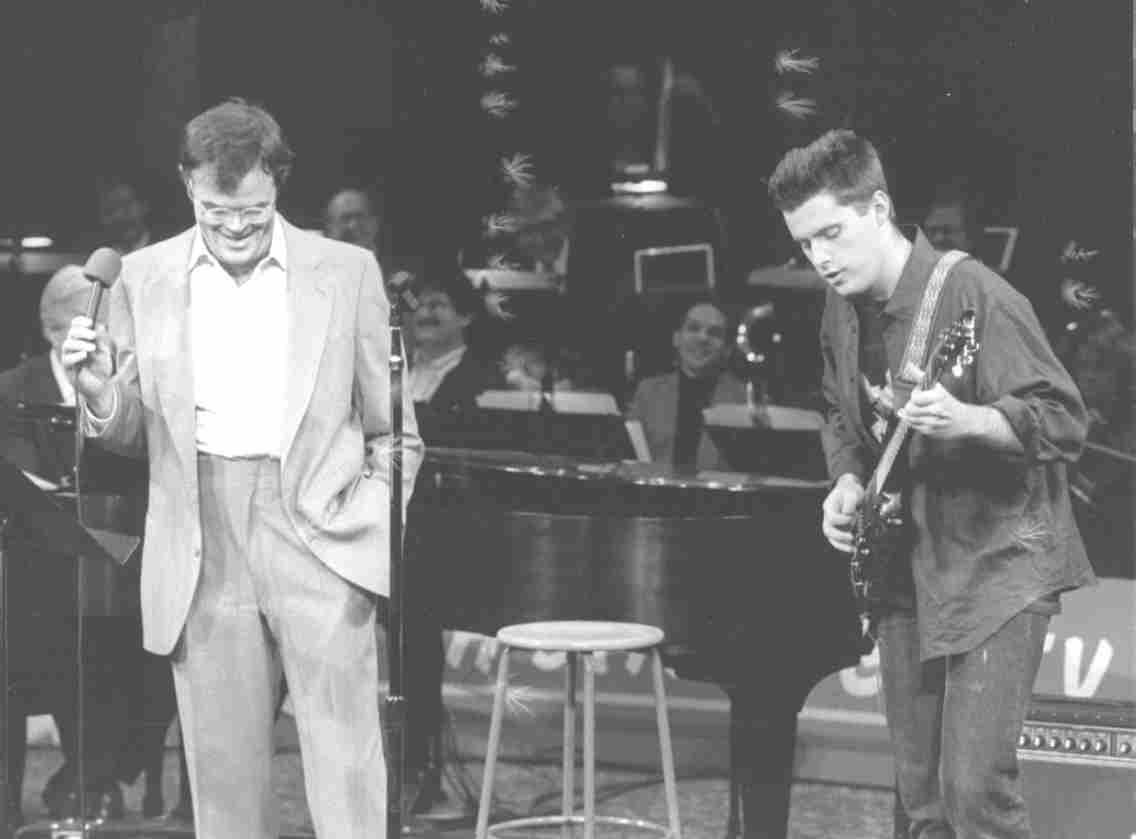

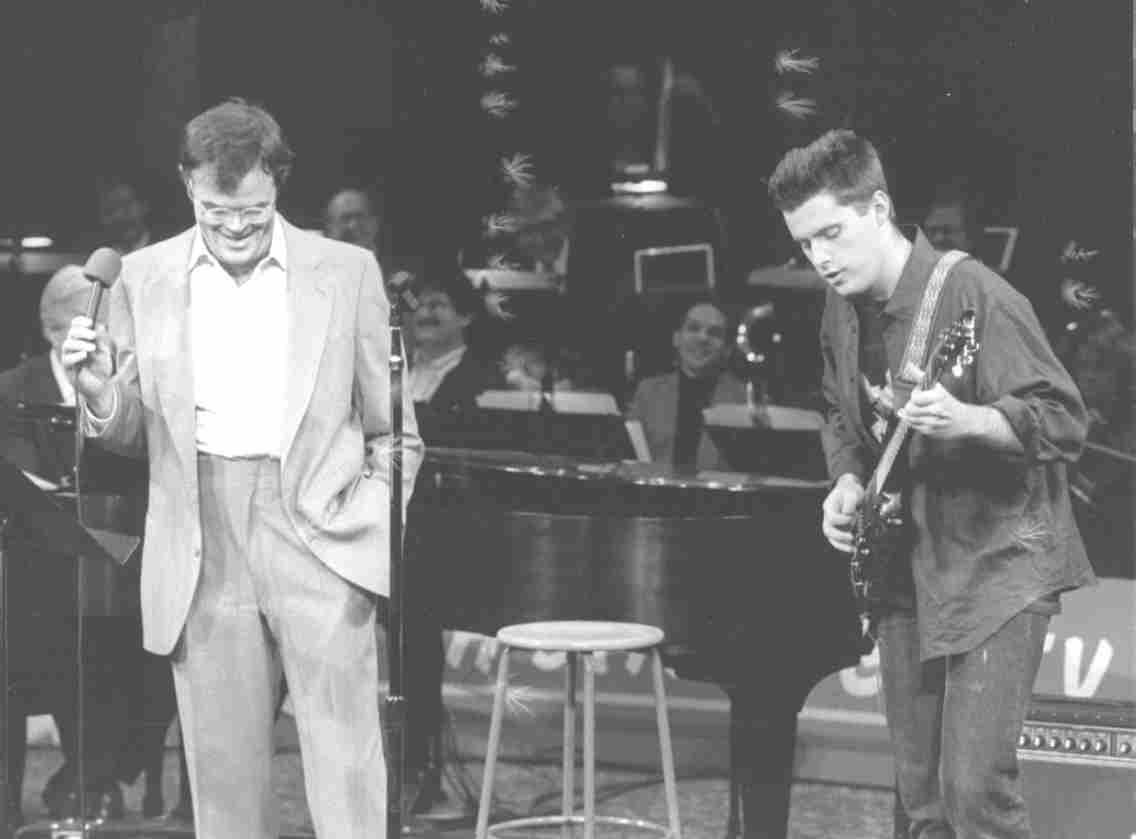

I did an eighteen-city tour one summer with Chet Atkins and his band, and in every show I recited James Wright’s poems “An Offering for Mr. Bluehart” and “A Blessing” (Just off the highway to Rochester, Minnesota, twilight bounds softly forth in the grass, and the eyes of those two Indian ponies darken with kindness) as my son Jason played a guitar underscore. James was a courageous man who wrote transcendent verse in the face of serious trouble and could be wildly funny at the same time. I was inspired one day to talk to the state Department of Transportation about putting James’s “A Blessing” on a plaque at a highway rest stop near Rochester— and an engineer named Kermit McRae got it done. It’s a great poem and the DOT can be justly proud of it—for years, “A Blessing” appeared in the State Fair crop art exhibit, the words spelled out in seeds glued to a sheet of plywood, a singular honor for a contemporary poet—and now it was written on stone. Celebrity is capable of good deeds. People asked me to do benefits, so I did, though the celeb aspect of it—my name in big letters on the poster associated with historic restoration or a cure for MS or a good woman’s run for Congress—felt unseemly and piggish. But how could I say no to a benefit in Rochester for a residence for transplant patients run by two Franciscan nuns? I sat with a ten-year-old girl named Chris, who had undergone months of chemo and now was waiting for a bone marrow transplant to try to cure a kidney tumor, a long shot, I was told. The will to live was palpable in that place. She wore a face mask. She sat next to me and leaned against me and we talked. She was a skater and she wrote poetry. So I wrote her:

GK and Jason Keillor, 1986.

My friend the ten-year-old Chris

Is a poet who writes about bliss

And as she waits

For a poem, she skates

And each LINE is a STRIDE just like THIS.

I was happy to meet her. What was hard was the much-too-extravagant gratitude of the sponsors. I wanted to tell them: “I’m not really a good person. I’m incredibly selfish. I drink very expensive whiskey and I fly first class. If only you knew.”

We honored Studs Terkel on his 86th birthday. I put him in a Guy Noir script, playing a gangster just as he’d done fifty years before on Ma Perkins and The Romance of Helen Trent. He wore a blue blazer, red checked shirt, red sweater, red socks, gray slacks, gray Hush Puppies. The audience sang, in honor of the old lefty, to the tune of the Battle Hymn:

It’s time for working people to rise up and defeat

The brokers and the bankers and the media elite

And all the educated bums in paneled office suites

And throw them in the street.

Let’s reverse the social order—oh wouldn’t it be cool?

Down with management and let the secretaries rule.

Let the cleaning ladies sit around the swimming pool,

Send the bosses back to school.

And a bathing beauty wheeled out a cake with eighty-six candles, the frosting melting from the heat. She wore a tiny top, her left breast bursting out of it, and when she adjusted herself for modesty’s sake, she almost popped out. The old man blushed. He reached over to assist her, then thought better of it.

I put together a committee to celebrate F. Scott’s centenary in St. Paul in 1996. Somebody else would’ve done it if I hadn’t, but I did a good job along with Page Cowles and Paul Verret and Patricia Hampl’s help.

Carol Bly considered FSF a “racist alcoholic social climber who stole his wife’s writing,” and she argued for a Thorstein Veblen celebration honoring the Wisconsin author of The Theory of the Leisure Class, a favorite of hers, published in 1899—I said we could hold a Veblen festival around my dining room table. Fitzgerald still had a large readership because he still sounded contemporary and he created a great narrator, Nick Carraway. The writers who pitied Scott and wrote his eulogies—Glenway Wescott, John Dos Passos, John Peale Bishop—all of them unread today except by a few graduate students, and Dorothy Parker, who looked down at his body in the coffin and said, “The poor son of a bitch”—Dorothy Parker is more quoted than read. The centenary was lovely, the University of Minnesota Marching Band and Fitzgerald’s granddaughters and great-grandchildren in an open car and Gene McCarthy and J. F. Powers in another, an Irish piper and a Bookmobile, the parade wending to the old World Theater, where Scott and Zelda’s descendants took buckets of Mississippi River water and threw it at the building and it was christened the Fitzgerald Theater. His old secretary Frances Kroll Ring was there, eighty, hearty and rambunctious, her memories of him vivid. He’d hired her via a Los Angeles employment agency when she was 22 and she typed up his last work and intervened with his friends and dealt with Zelda and daughter Scotty and disposed of the empty bottles, and then he arose from his chair, clutched his heart, and died, 44, a famous American failure, and she defended him as a conscientious gentleman and man of letters working hard in the face of addiction and financial distress. She was a peach. It was amazing to be in the same room with her, his last and best heroine.

The statue committee decided not to put Fitzgerald on a pedestal, so he stands on the ground, coat over his arm, as if waiting for his ride to come. He was 5'9" in real life, which seems shrimpy today, so the sculptor gave him two more inches. There was a reading of The Great Gatsby at the Fitzgerald Theater, a packed house, the entire novel, with one intermission. The book reads well, a tribute to the author who survived the small mean anecdotes told about him. Survival: who can explain it? Fitzgerald survives.