27

Mitral Valve

THAT SPRING OF 2001 I was inducted into the Academy of Arts and Letters up on 155th Street, nominated by John Updike and Edward Hoagland, a fine honor for Anoka High School and my teachers and a shock to me. Standing in front of the Artists and Lettrists was nice, but the people who should’ve been there, Mr. Buehler, Warren Feist, LaVona, didn’t get invited. They would’ve been astounded. As for me, a humorist needs to avoid distinguishment because comedy is not about triumph, it’s about shame and defeat. A humorist has a moment of passion in a VW with a tall dark beauty and to avoid the stick shift they get into the back seat, which is too tight for him to remove her pantyhose, and he bangs his head on the ceiling and she has a laughing fit and Erectile Disillusion occurs and of course he is disappointed but he also thinks, “This is good, I can write about this,” which I just now did.

The Academy had always been hospitable to humorists: Mark Twain was a charter member, George Ade got in, Finley Peter Dunne, the great Don Marquis, Art Buchwald, Peter DeVries, Calvin Trillin, Ian Frazier, and David Sedaris, so it was not like entering the Academy of Irish Setters or Veterinary Aromatherapists. The ceremony did not make me dizzy, I know who I am, a hardworking writer, one of thousands, a deadline man, a monologist who occasionally wanders onto the high plateau of novelisticism and the greenhouse of sonnetry. It was a shock to go in and stand between Philip Roth and Harold Bloom at the urinal. Of course, it would’ve been even more shocking to stand between Ann Beattie and Joan Didion.

Being admitted into an august Academy is exciting for one in the amusement business as I am. The citation about me used the word “hilarity,” which was kind of them and made me think of the young woman I saw in a vaudeville show in London, who played a very sexy “America” on the kazoo, fluttering and fiddling with her décolletage, and then very demurely dropped her drawers, pulled a second kazoo out of her bosom and stuck it up under her long skirt into a private place and proceeded to give us (we imagined, we dared to hope) a two-part rendition of “America,” the alto part from her nether region, a very accomplished orifice duet, all with the innocence of a 4-H’er performing at the county fair. It was musically flawless, it bent the borders of decency, and it made some of us laugh our heads off.

A lady performed on kazoo,

And then she played music on two,

One in her kisser

And one in her pisser,

My country, America, ’tis of you.

I envied the elegance of her joke, the kazoo up the wazoo, and didn’t want the induction into the Academy to tempt me to be distinguished and a couple weeks later, I did a beautiful vulgar parody of Paul Simon’s “Sounds of Silence” with gagging and retching and farting that moved millions of listeners with visceral intestinal distress. (Fred Newman did the sounds, I was only the writer and singer.)

Hello darkness, my old friend

I have gone to bed again

Because a virus came in to me

And I’m feeling tired and gloomy

And my head hurts and I’m achy and I’m hot

And full of snot

I hear the sound of sickness.

A modest start but it went on to thrill every thirteen-year-old boy in the audience:

I came home and went to bed

And felt a throbbing in my head

And I’m getting the idea

I will soon have diarrhea.

What Fred did at this point can’t be represented in print, but it was vivid and meaningful and made the room spin.

Why am I the one who’s fated

To be so awfully nauseated

And something like silent raindrops fell

And what a smell

I hear the sounds of sickness

It was the only time public radio presented a man at the brink of regurgitation. “Sounds of Sickness” as done by Mr. Newman was absolutely in the “America” kazoo duet class.

It was quite a year, 2001. My father died, I got Academicized, I entertained thousands of thirteen-year-old boys with a song about vomiting, I began to notice my own dizziness and shortness of breath onstage, and then I flew down to Nashville to speak at Chet Atkins’s funeral at the Ryman Auditorium, his designated eulogist. He died at 77, after a brain tumor and a stroke. He wrote me after the tumor that he was having to relearn the guitar and he sort of did—he played on the show after the stroke, though he could barely make chords. “I’m getting better,” he said, “but I’m no Chet Atkins.” We wheeled him out onstage, guitar in hand, to a big ovation, and we turned off his mike as Pat Donohue sat directly behind him and played Chet’s part so well that nobody noticed. I visited him in Nashville after that and reminisced about our touring days—the flight on the charter plane that ran into heavy weather over the Rockies, and Paul Yandell said, “I can see the headline, Chet Atkins and Garrison Keillor and Five Others Disappear in Storm, and I’ll be one of the Others”—Chet sat slumped down and never looked at me and didn’t say much. I’m sure he felt wretched and he didn’t want to be seen like that, old and sad, wrapped in an overcoat, holding a guitar on his lap, unable to play it. He wanted to be alone with Leona and his daughter, Merle. So I slipped quietly away. There was no consolation, only family. In the eulogy, I quoted from his letters. He was a natural writer. He wrote: “I am old and still don’t know anything about life or what will come after I am gone. I figure there will be eternity and nothing much else and I will probably wind up in Minnesota and it’ll be January. What I do know is that Leona has stayed with me through four percolators. We counted it up yesterday. She is mine and she is a winner.” I said, “Let us commend his spirit to the Everlasting, and may the angels bear him up, and eternal light shine upon him, and if he should wind up in Minnesota, we will do our best to take care of him until the rest of you come along.”

The season continued, shows in Norfolk, Seattle, Memphis, Tangle-wood, and Wolf Trap, I kept writing. Once again we take you to the hushed reading room of the Herndon County Library for the adventures of Ruth Harrison, Reference Librarian. A woman who loves classical literature but longs for illicit love. And then Roy Bradley, Boy Broadcaster. “Even hard words like sagacious and hermaphrymnotic flowed from his tongue like cream from a pitcher, thanks to his having grown up in the town of Piscacadawadaquoddymoggin.” I felt wheezy on stage and to avoid panting on the air, I parked myself onstage behind the piano next to the drummer. Jenny mentioned the wheeziness to our cousin, Dr. Dan Johnson, who directed me to the Mayo Clinic where Dr. Rodysill listened to my heart for a minute or so and gave me the lowdown: mitral valve prolapse, the very defect that kept me off the Anoka football team and turned me toward newspapering. The defect that killed off several Keillors, including two uncles my age. A surgeon was summoned, Dr. Thomas Orszulak, who looked like the tenor Jussi Björling, was from Pittsburgh, the son of immigrants, the first in his family to go to college, a Harley enthusiast and a fly fisherman who tied his own flies. It was Monday. He had an opening on Wednesday morning. I’d planned to fly to Europe, and instead I went up to the cardiac unit. It all felt very straightforward, tremendously competent people around me. “Open-heart surgery,” which was front-page news in my childhood, now a well-traveled road. I signed up for an early morning slot, July 25, 2001.

Tuesday afternoon, I drank a gallon of liquid laxative to empty my bowels, and a burly man came in to shave my groin. Father Nick came in and prayed with Jenny and me, and we took Communion. I slept well and took a shower at 5 a.m. and was anointed with antiseptic and given muscle relaxants and wheeled out on a gurney with my wife beside me, her hand on my shoulder, she kissed me twice and then into the chilly OR I went and was slid onto the glass operating table. A moment of pleasant chitchat with the anesthesiologist and then I was in a small boat in a deep fog, bumping up onto a sandy shore in the dark, surrounded by angelic beings with Minnesota accents, Erin and Erin and Cliff, who removed the tube from my mouth, a simple breathing tube but it felt like the tailpipe of my old Mercury, and they assured me that I was alive, and I’ve been grateful for that ever since. I was in the ICU and it was five hours later, and then Jenny was there to say hi and they wheeled me back to my room.

The first big test was urination: could I do it? The catheter was removed and—he shoots, he scores! I took a shower. I took a walk down the hall, holding a nurse’s arm. The surgeon’s assistant inspected the scar, the cardiologist took my blood pressure (Excellent! ), Dr. Rodysill came by to explain the sewing of the mitral valve, the angelic beings dropped in, Jenny returned and sat on the bed, holding my hand.

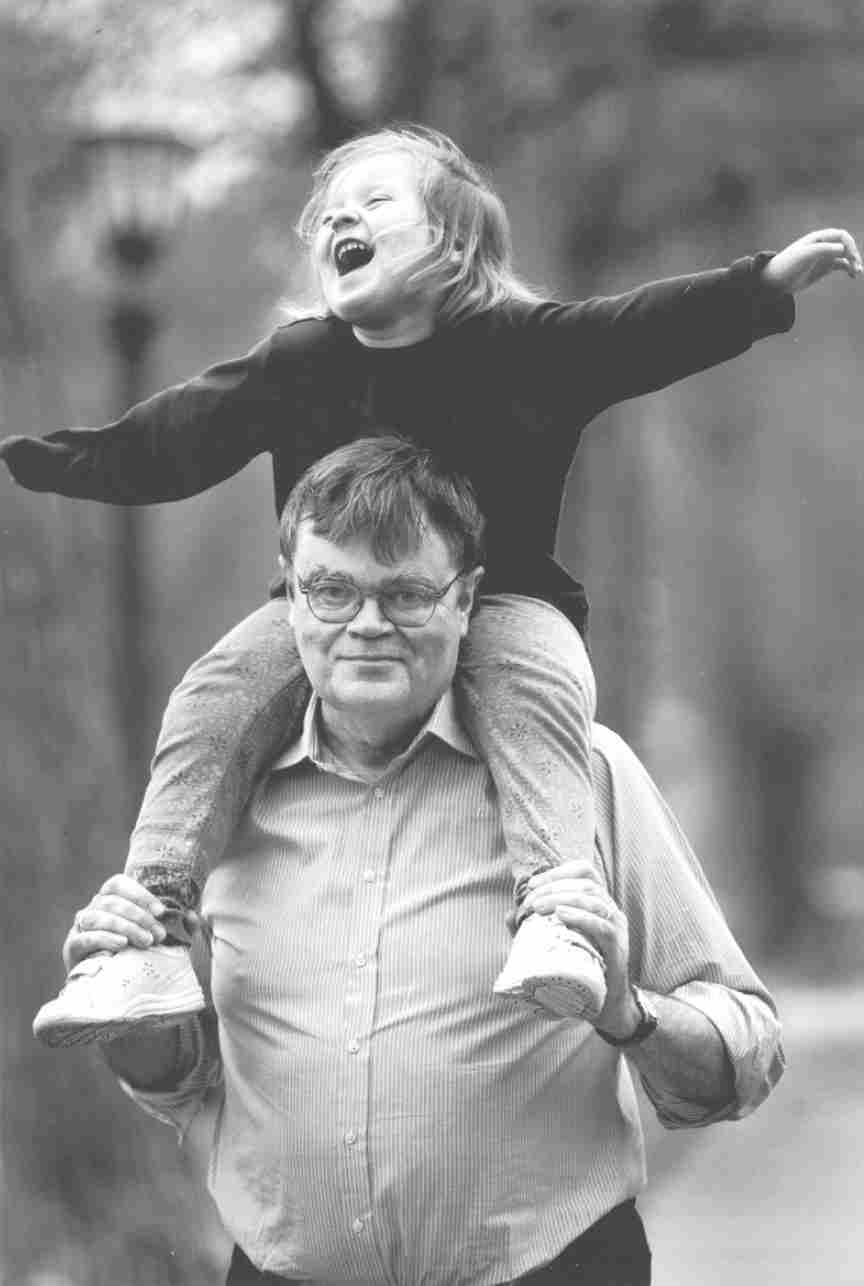

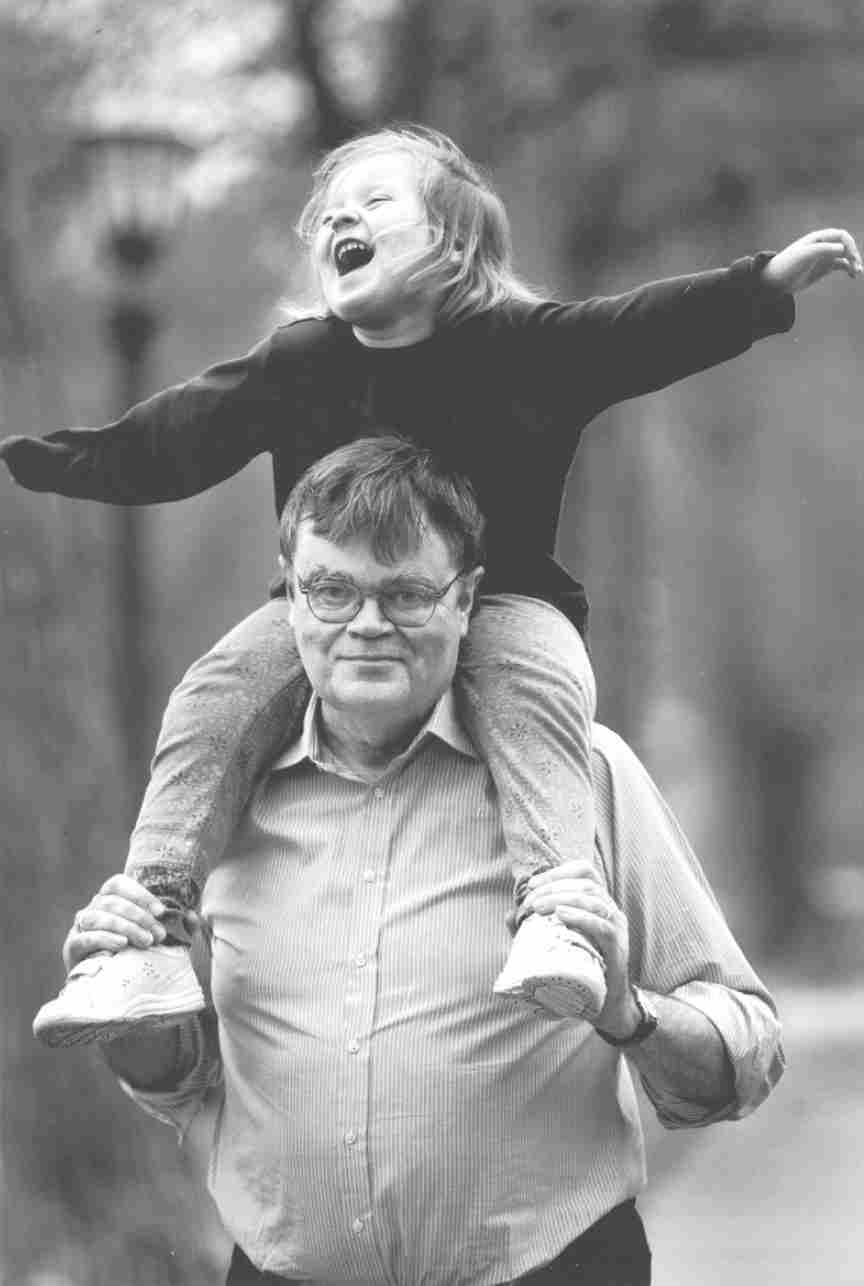

I was glad to be surrounded by brisk Minnesota women in blue uniforms who sized up the situation when they walked into the room and went right to work. “So how are we doing then?” they said. They made small talk to put the patient at ease. They cared and their caring was not generic, they’d been brought up to care. And when I was released and went home, every sense was heightened, every day beautiful, to rise early and smell coffee and pick up the Times and be alive. I lay on the chaise in the backyard feeling the luxury of ordinary life and did the crossword and watched my daughter as she wrote Daddy in green chalk on the driveway. One afternoon, I saw her swinging high into the air on the Hooleys’ rope swing, laughing on the backswing up into the branches of the apple tree and a gasp of delight in the moment of weightlessness, and then she put her feet down and skidded to a stop and toppled over in the grass, laughing. My girl.

She was delighted with her speech therapist, Amy, and her physical therapist, Kim, and her nanny, Katja, all of them working on her speech and agility deficits. She’d been diagnosed with verbal apraxia, which turned out to be only one aspect of the problem, and clearly, she wanted to be with people, she loved company, and wanted to take part in things. She sat with her Czech nanny Katja, and later Kaja, arms entwined, imitating how they crossed their legs and brushed back their hair, kissing their hands, praying to be in their club. Sometimes I’d say, “It’s been a quiet week in Lake Wobegon, baby,” and she recognized the line and laughed. Eventually she was diagnosed as having Angelman syndrome, a genetic slipup that can be catastrophic, but in her case, thanks to her mother’s determination and the help of dedicated therapists and the grace of God, she grew up articulate and humorous and good-hearted, and whatever her deficits may be, she makes up for with a sense of comedy.

Maia and GK, 2001.

Once we visited Prague with Kaja and sat near the Vltava, below the Castle, a stone’s throw from the tourist mob on the Charles Bridge, near the Church of St. Nicholas, a big whoop of High Baroque with cherubs like glazed doughnuts and a marble bishop throttling Satan, near Franz Kafka’s house on Celetná Street. He dreaded noise, footsteps, the gramophones of neighbors, his sisters’ canaries, the bonging of church bells, the jangling town hall clock—he felt like he was living in a bowling alley. Now the town square is packed with tourists videotaping the clock, which has apostles instead of cuckoos, and drinking beer and listening to jazz bands. Kafka’s problem was the lack of a daughter. He should’ve gotten his fiancée Felice pregnant and today the word Kafkaesque wouldn’t mean “nightmarish” or “weird,” it’d mean funny. “What do you name a guy with no feet? Neil.” “Very Kafkaesque.”

A month later, I was on the move. Lake Wobegon Summer 1956 came out, and I did the usual book tour, two cities a day, two readings in two theaters. The book did well enough, and Viking signed me to write three more. The tour took me to New York for a reading September 10 at a bookstore in Union Square. A good crowd for a Monday evening. I talked about parts I had omitted from the book I was promoting, then stood around and signed copies. It was almost midnight when the last dog was hung. Holly and Dina from Viking were still there and Anne (Dusty) Mortimer-Maddox, a friend from New Yorker days, and we four crossed the square to a seafood restaurant on the south side of 14th. The place was packed and the maître d’ led us to a table on a narrow balcony, and we camped there for two hours over martinis, oysters, scallops and linguini, some not-bad wine, and talked. Dusty and I gossiped about the old crowd at the magazine. She talked about the filthy barroom language that Pauline Kael liked to put in her movie reviews to get Shawn’s goat. Kael once referred to an actress as “a walking advertisement for cunnilingus” and Mr. Shawn wrote in the margin: Why does she do this? Why? It was a splendid fall night, festivity in the air and New York magnificence. We could see the lights of the World Trade towers downtown. Holly said that 1 a.m. in Manhattan made her feel as if she were twenty-four again and just arriving in the city. Dusty announced that she was seventy but felt thirty-seven. “Aging is the opportunity of a lifetime,” I said. We were all feeling oddly ecstatic, sitting up there above the canyons of lights, working people who’ve allowed themselves to stay up late on a warm September night, and seven hours later, two airliners crashed into the towers and fire and smoke billowed up and office workers leaped to their deaths and valiant firefighters hauled hose up the stairways and an hour later the buildings collapsed.

I was in my kitchen on 90th Street that morning, and heard a big plane flying low over the Hudson, and half an hour later a friend called and said, “Turn on your TV.” I didn’t have one so I went over to Docks, where a crowd was clustered in the bar, watching a news clip of people falling, arms outstretched, from high floors. It was too painful to watch. Men and women who walked these streets with us had, on a Tuesday morning, found themselves engulfed in horror and death. We read in the Times how many of them stifled their panic and looked out for the others on their floor and many of them, seeing that death was inescapable, called home on their cellphones to say, “I love you. Take care of the children. Have a good life.” They called in the midst of smoke and panic to give a benediction. Weeks later, the city released some of the 911 calls from the Trade Center, the woman on the 83rd floor, overwhelmed by smoke, crying, “I’m going to die, aren’t I? I’m going to die.” A man on the 105th floor, gasping for breath, who screamed, “Oh my God” as the building started to collapse. They were people whom we might have sat near in a theater or restaurant, who suddenly found themselves facing the abyss, and firemen ran into the building to save them and died in the collapse, and it was all on TV. And then the politicians came out of hiding to seize the day, and Mr. Giuliani put on his public face and Mr. Bush mounted the wreckage with bullhorn in hand and vowed vengeance. The cops and firemen who climbed the stairs represented New York at its most courageous and caring, and the self-aggrandizing Giuliani was New York at its money-grubbing worst. He went around giving speeches on leadership for a hundred grand a shot, getting standing ovations as a stand-in for the police and firemen who died because police helicopters who looked down at the inferno and saw that the buildings would collapse couldn’t get word to the fire chiefs on the ground who sent their men up the stairs to die. Giuliani had known about the radio problem for years and failed to get it fixed, and in the patriotic fervor post-9/11 escaped blame. Meanwhile, Bush, who had ignored earlier intelligence warning of terrorists flying planes into tall buildings, claimed Iraq had weapons it didn’t have and sent 4,000 American men and women to die in an evil mess with no clear purpose and no end. It was a wretched time in American history. Those lives were not given for their country, they were taken, stupidly and carelessly. Politicians sacrificed them.

Two nights later, my neighbors Ellie and Ira and I went down to the Village for dinner. Smoke in the air, trucks of debris roaring past, and yet New Yorkers were eating supper in outdoor cafés, resuming normal life as an act of resistance. You tried to blow us up: we’ll show you, we’ll go out to eat. It was an Italian restaurant, we talked for two hours, and not a word was said about the death and destruction. We talked about everything ordinary because we had no right to comment on the horror. We had read about the heroism of firemen who dashed into the burning towers, dragging hose up the stairways, who felt deep down the direness of the situation, a hundred-story tower with a huge gaping hole in the middle—dashing into the building went against basic human instinct. But there were people trapped above so up they went. Nobody cared to be the first to turn tail and head for safety. We thought about them in silence, eating our linguini in clam sauce. Heroism on such a scale demands you revise your views of your fellow man.

The next Friday evening, a spontaneous event: thousands of residents stood outside their apartment buildings, holding lit candles, singing about the spacious skies and the land of the pilgrims’ pride. I walked around the Upper West Side listening to it, a wholly other New York than anything I’d seen before. At LaGuardia, when I resumed the book tour, I met a young man who’d been on the 61st floor of the south tower, taking a training program. He said, “It was the worst day of my life, and the best.” He looked radiant. I didn’t ask how he escaped, and he didn’t say. I talked to Jenny back in Minnesota: musician friends of hers went to a church near Ground Zero to play music for salvage workers on their rest breaks. They went day after day to play Mozart and Haydn.

September 11 was a tragedy, and the tragedy was George W. Bush standing on the smoking ruins and promising revenge and promoting the fiction that war in Iraq and Afghanistan was to defend the country against terrorism. Congress, which once spent an entire year investigating a married man’s attempt to cover up an illicit act of oral sex, showed little curiosity about a war waged on false premises that killed hundreds of thousands and led our own people to commit war crimes and squandered hundreds of billions of dollars.

I loved the road, doing solo shows after 9/11. Ann Arbor, Tulsa, Fort Pierce, East Lansing, Santa Cruz. Five nights in five cities, then the Saturday broadcast. I worked on a new book on the plane, arrived in a town, got to the hotel, took a nap. Walked to the theater, walked in the stage door, said hello to the crew, paced for ten or fifteen minutes, then took my place behind the curtain and made my mind go blank. The stagehands relax by the rope rigging, an easy night for them, accustomed to loading in massive sets and flies, and tonight, it’s one microphone and one wooden stool. The house lights dim to half, the recorded announcement about turning off your cellphone, and the crowd waits, whispery— then I drift out into the spotlight, into the applause falling like warm rain. I stop and bow. And I sing:

Here I am, O Lord, and here is my prayer:

Please be there.

When I die like other folks,

Don’t want to find out you’re a hoax.

I would sure be pissed

If I should’ve been an atheist.

Lord, please exist.

And then segue into “My country, ’tis of thee,” and the audience sings, and “God Bless America,” and that takes care of September 11th, no need for comment, and I walk back and forth, talking, picking out faces in the crowd, talking about Lake Wobegon, about my classmate Julie who liked to wrestle with me in sixth grade, the Boy Scout winter camping trip when I left the tent to pee and my extreme modesty made me wander far into the woods and almost freeze to death. The Uncle Jack story, in which his old wooden rowboat springs a leak in the middle of the lake and I try to stop the leak with my bare foot and he cries out O Captain! my Captain! our fearful trip is done, the ship has weathered every rack, the prize we sought is won. And the story about the pontoon boat carrying the Lutheran pastors that capsized in the wake of the speedboat and the great dignity with which they toppled overboard. There are good laughers in the crowd, a cackler, a whooper, and a guy who sounds like an old truck engine turning over. People laughing at the stories and also at the laughter. At the end, the audience and I sing “Good Night, Ladies,” “Goodnight, Sweetheart,” “Happy Trails,” “Red River Valley,” and I bow and exit to applause and stand behind the curtain, counting to ten. In theaters of a couple thousand seats all full of people, the audience is excited by its own applause, so you don’t take it too personally. You count to ten and if you hear diminution, you walk away, but if it’s holding steady, you walk out for another bow. My friend, the conductor Dennis Russell Davies, showed me how to bow years ago, and I try to do it right: stop, hold out your hands to the crowd, smile a genuine smile, bend, look at your fly for a count of five, stand, smile, march off. After the encore bow, the applause fades quickly—the show was two hours long and the audience is older and aware of its bladders so I walk backstage, where the stagehands sit around a table, eating the last of their supper, an awkward moment since they have no idea who I am or what it was I did out on stage—they’re jazz guys, maybe C&W, but I always stop to say thank you, and then out the stage door I go and down the alley and cross the street and slip in the side door of the hotel and ride the elevator to the sixth floor and my room. Take off the suit and shirt and tie. Take my meds. Crawl into bed, feeling good—I gave good value to a couple thousand people and enjoyed doing it—and fall asleep. Up at 5. Make coffee. Three precious hours before I leave for the airport, the best time for work, so I go to it. There is always more to do. A writer’s job never ends. This is a good life, an easy life. I hope it never ends, knowing it will.