32

An Easy Descent into Oblivion

THE SHOW BUSINESS HAS ITS moments—like standing eye-to-eye with Heather Masse and singing “Under African Skies” and feeling her voice take hold of my own, or seeing an audience fall apart as Tim Russell does Donald J. Trump singing “I Feel Pretty”—but there’s also a lot of time spent sitting and waiting. You arrive early in case there are problems, and sound check is done at 2:30 and you sit in a dressing room waiting for a 5 p.m. show, try not to think about it, and soon it’s 3. I didn’t socialize backstage. I liked to sit still and become nobody, in keeping with LaVona Person’s advice when I was fourteen: “It’s not about you. It’s about the material.” When I walk out onstage, I’ll be astonished by the applause, and then the material will spring to mind. Meanwhile, I sit in a room and empty my mind and odd things drift through it. My vacant chair at our family’s dinner table as I stand outside looking through the window. Hitchhiking late at night on the West River Road, a car approaches, slows down for a look, and resumes speed. The feeling when the hockey team scores and we all jump up to sing “Minnesota, hats off to thee, to your colors true we shall ever be.” And the prospect of retirement and decrepitude and not doing this anymore.

A Prairie Home Companion was wending its way toward the exit. We did a show in Baltimore at an open pavilion in the Inner Harbor, near where Francis Scott Key wrote the words, and a couple thousand people sang the national anthem in the key of A, with gusto, the sopranos floating up high over “O’er the land of the free.” When the British attacked Fort McHenry in 1814, they were quite justified, American pirates hav ing operated out of Baltimore harbor to prey on British cargo ships. The bombardment was their tit for our tat. Mr. Key wrote his lines in a fever of righteousness hardly supported by the facts. But it’s a great rouser, and we all stand and feel good when the rockets go up and the bombs burst, and what would life be without mythology? Rather flat.

We were ten shows from the end, then nine, then five, an easy descent into oblivion, but in each of the cities a few reporters came backstage to ask, How does it feel? And What do you see when you look back? It felt good, of course. I loved the show. When I looked back, I remembered the Hopeful Gospel Quartet and the Red Clay Ramblers singing Carter Family songs and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott the Brooklyn cowboy and Allen Ginsberg proclaiming Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” like the prophet Isaiah of New Jersey—the mezzo Marilyn Horne singing her favorite tenor aria, “Celeste Aida,” in the tenor key, an astonishing gender switch—Chet Atkins and Leo Kottke playing “Living in the Country” aboard an elevator rising slowly to stage level at Radio City Music Hall, the wave of applause that almost drowned out the tune, and the tune riding through the wave— Chet singing “I Still Can’t Say Goodbye” to his dad and the show at St. Olaf College where the audience sang Children of the heavenly Father safely in His bosom gather, nesting bird nor star in heaven such a refuge e’er was given in pure four-part harmony, impromptu, which listeners thought was a choir, but it wasn’t, it was just eight-hundred Lutherans. I made fun of Lutherans, for their lumbering earnestness, their obsessive moderation, their fear of giving offense, and I never felt so exalted as when I stood in the midst of a roomful of them (or Mennonites) and we all sang together.

And I remember Jearlyn and Jevetta Steele belting out “Natural Woman” as they boogied big-time at the microphone and the duo of Gillian Welch and Dave Rawlings and the sisterly harmonies of the DiGiallonardos with Rob Fisher bouncing at the piano with the Coffee Club Orchestra, and Soupy Schindler playing power jug and Peter Ostroushko’s mandolin études and how astonishing it was, in the midst of our gumbo of comedy and mumbo-jumbo to hear haunting voices like Aoife’s and Geoff Muldaur’s and Helen Schneyer’s. And then there was Fred Newman impersonating a man on a 50-below morning trying to start a car that only wants to die and praying through clenched teeth and hearing angel wings and ocean surf and tropical birds and the swing of a golf club and the ohhhh of an admiring crowd. Everything Fred did was masterful. I revised “Somewhere Over the Rainbow” for him:

Somewhere there’s an old cabin

By a lake

Where I awoke to the bacon

Coffee and pancakes

Somewhere north of the Cities

Neath the moon

There I lie in the night and hear the distant loon (LOON CALLS).

Fred was the Birgit Nilsson of loon-calling, the state bird of Minnesota, and he made it into a work of art, filled with tender longing and bravery and the knowledge of mortality. His loon was luminous. He also did ominous ad hominem hums that were memorable and momentous.

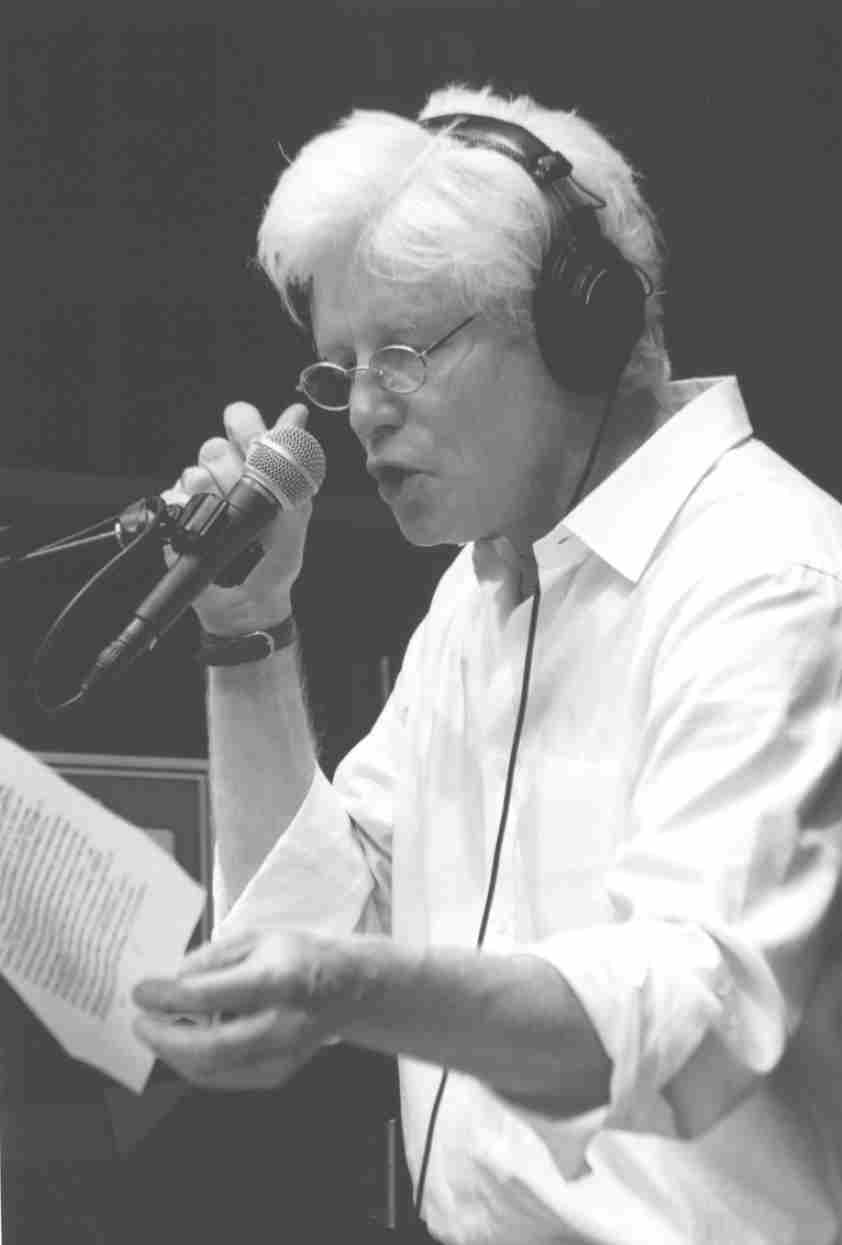

Fred Newman calling a loon.

That last run of shows was a beauty, the mixed pleasure and regret of the audience. For years I’d been so busy writing the show that I didn’t see the big picture until the show was coming to an end: People listened, some of them from childhood into middle age. The show became a part of their lives like an oddball uncle who likes to natter and tell jokes. I set out to carry on the sort of show I loved as a kid, which was now a museum piece or close to it, and it moved me that the show was loved by people too young to remember the original. In years to come, younger people would put a hand on my shoulder and say, “Love your work,” women would say, “I used to spend my Saturday nights with you.” The show was not brilliant or revolutionary, but it had the genuine affection of its audience.

The last show was at Hollywood Bowl, July 1, 2016, with Heather and Aoife and Sara Watkins and Sarah Jarosz and Christine DiGiallonardo as duet partners, and the duets were about enduring love and the Lake Wobegon monologue was about the dead—last monologue, so I get to talk about what’s on my mind—Father Emil who died of a heart attack while on a tour of the Gettysburg battlefield and was distressed to fall behind Confederate lines, and Jack of Jack’s Auto Repair whose ashes were put in his wife Loretta’s coffin though she had made it clear she didn’t want them there, being as tidy as she was, and my classmate Arlen who went through the ice on his snow machine, trying to impress Barb whom he was crazy about. She waved to him and he waved back and down he went. She married his twin brother, Arnie, which seemed to prolong the grieving process, sleeping with a man who looked exactly like your lost love, but he gained weight and his hair got thin and he turned out to be a good husband, which she eventually realized, and he adored her and Arlen was dead, and that made all the difference. Not a great monologue, which was fine, to let the audience down gently.

There was a half-hour encore of audience singing at the end—“I Saw Her Standing There” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” “Can’t Help Falling in Love with You,” and “Auld Lang Syne,” and a dozen others—and I bowed and took a wrong turn from the stage and wandered through the trees out into the crowd heading for the parking lots and was trapped there for an hour being manhandled by fans, a life-size male toy in their hands. I grew up an awkward misfit, no hugging or horsing around, but in the scrum of those fans I was extensively pawed over, an inert object with no will of my own. People grabbed an arm, put a head on my shoulder, crouched between my legs, planted themselves flat against me as cameras clicked and hummed. Someone stuck a hand behind my head to make my ears stick out, covered my eyes, I was hugged, squeezed, clutched, patted, rumpled, fist-bumped, high-fived, groped—radio had been an intellectual exercise, and now I was a physical object, to be embraced, fondled, clasped, latched onto, poked, embraced, climbed on, and heartily harassed. I was a prime rib at a piranha picnic. It was like the winning team pileup on the football field. The mob grew, people gathered around to get a hand on me, whole families, children climbed into my arms and stuck their fingers in my hair. A dignified lady almost my age grabbed a buttock and gave it a good feel. I was not a distinguished broadcaster, I was a beloved dotty uncle, exactly what I had wanted to be without knowing it. No need for a Peabody or DuPont. No need for MPR to throw a big party. (They didn’t offer, so I didn’t need to decline.) That crowd was all the confirmation a man could want, the pushing and pummeling of loving strangers. It was a transforming experience. I accepted that I was loved.

I was in a taxi in New York a year later and heard my voice on the cabdriver’s radio talking about a baseball game in Lake Wobegon. The cabdriver was a big man, African, wearing a dramatic black-checked head wrap. I said, “I’m going to LaGuardia, Terminal D, please,” and he turned around and said, “Your voice is familiar.” I laughed. On the radio, I was telling about an exhibition game the Lake Wobegon Whippets had played in 1942 against the Showboats and their one-armed pitcher, Duke, and a catcher, Mark, who was legally blind, and a border collie named Spike playing second base. It was wartime and the good ballplayers were in the Army.

The cabdriver eyeballed me in the rearview mirror. The man on the radio was talking about the dog coming up to bat with the blind man on third. The dog held the bat between his teeth and his job was to get a base on balls, his strike zone being about fifteen inches, shoulder to knees. The driver said, “You’re the man on the radio.” I nodded yes. He said, “I’m from Ethiopia. I learned my English from that show.” He showed me a bag of tape cassettes, labeled “Minnesota.” He’d recorded them off the air. The dog fouled off two bunt attempts, and we pulled up to Terminal D. I gave the man a copy of my book of sonnets and he had me sign it to his wife, Sarah. I said, “It’s an honor to meet you,” and we shook hands. I gave him fifty bucks for a tip, and when I got into the terminal, I wished I’d given him more. I’d done the show for my own amusement, and it amazed me to find out I’d also been teaching English as a second language. My mother wanted me to be a teacher, and now I’d helped a man from Ethiopia learn English.

Usually on a flight home to Minnesota, the plane crosses the St. Croix and banks to the north and comes in low over farms and the Minnesota River, but coming home after the show in LA, the plane took a big loop around the metro area and made a tour of the geography of my youth, a dreamy celestial view of the town of Anoka where the Rum meets the Mississippi and where Mr. Andersen handed me a copy of The New Yorker as he said, “I thought this might interest you,” and Mr. Buehler, worried about me and the power saw, dispatched me to LaVona Person’s speech class where I recite an unrhyming limerick and get a big laugh, and Dr. Mork, who brought me into the world, decided to spare me from football and Mr. Feist gave me a desk in the front window of the Anoka Herald, the flatbed press rumbling down below. And then down the West River Road and Benson School, where Mrs. Shaver asked me to read aloud to her while she corrected papers, and over north Minneapolis where I biked past the factories and packing plant to go ruminate in the great sandstone library, long since demolished, but the great grassy Mall of the University is majestic below and the Union where I did a private daily newscast, and we descended over the blocks of little bungalows where Mother grew up, a glimpse of the Meeting Hall and 38th Street where I tried to buy a cheeseburger with stolen money, and then the wheels lowered and we sailed in over Don and Elsie’s house and the old Met Stadium and onto the runway.

I came back from LA for the reunion of the Class of 1960. People asked, “What you been up to then?” and I said, “Not much.” My classmates Marvin Buchholz and Wayne Swanson were still farming, Bob Bell looking young and fit, and so did Rich Peterson, having taught phys ed all these years. His parents ran Cully’s Cafe out back of the Herald office where I worked, and I’d come in to eat a hot beef sandwich while reading galley proof. I hung out with Billy Pedersen, now retired as head of the state hospital in St. Peter. Carol Hutchinson was a librarian, Vicky Rubis a schoolteacher, Mary Ellen Krause had kept our hometown’s enormous Halloween parade going all these years. Liz Johnson, still a list-maker, organized the thing, and I stood and talked to Don Carter and Wayne West, whom I’d barely known in high school, and now, by the simple fact of being 75, we were pals. Earl Krause had become a noted oceanographer who had traveled most of the watery world and every continent. Some friends were missing, ambushed by old age. I thought about Corinne, gone at 43, still a mystery. If she’d only survived that dark April night on Cayuga Lake, she’d be here with us, laughing.

The secret is not a serene disposition,

Or spiritual strength

Or a strong core, regular exercise, or a good physician:

The secret of longevity is length.

Don’t put rocks in your pockets.

Every day take a long walk, it’s

Just that simple. By and by,

Someday you’ll be as old as I.

When the show ended, I started to truly appreciate it, which you can’t do when you’re in the thick of things, beating up on yourself to be better than you are, and then in the small stillness that follows, you start to comprehend the miracle of the past forty years that a small staff and an enormous cast had created. Over time, the show had bonded in fellowship with a diverse constituency of college profs and prison inmates, Republican moms, African cabdrivers, small-town teachers, renegade Baptists, loony libertarians, soybean farmers, and countless etceteras, and one by one they show up in my life with smartphones to take a picture, and I stand beside them and put an arm around their shoulders and I think, “How in the world did this ever happen?” A woman tells me her story: In the hospital, her premature baby, 2 lb. 2 oz., with chronic pneumonia, crying under an oxygen mask, and she put a boom box by him and played the tape of my story about Bruno the Fishing Dog and the baby stopped crying; he listened and relaxed and he survived and is now a junior in college. By way of radio I became a friend of people who, as an old evangelical and literary gent, I’d likely have scorned mercilessly in real life. Scorn came easily to me. I am biased against tattooed people, grabby people, people who put oregano in everything, blowhards, emotional drunks, and scornful people like myself. (Also bolo ties, wind chimes, and mood music, but those vanished long ago.) But now a young woman gives me a long look and says, “I grew up listening to you.” She went to MIT, majored in chemistry, writes scholarly articles about sanitation, raises her three kids, has a good life. (Also a spiderweb tattoo on her neck.) And then she pulls out a phone and I put my head next to hers, and she snaps our portrait. A miracle to be an intimate pal of a complete stranger.

Once a year or so, someone says, “I was at that show in Rochester where you leaped up into the ceiling.” It was at a community college, a makeshift stage—plywood sheets on steel legs—which was moved back under a concrete overhang to make room for more folding chairs. The lights dimmed, I ran and leaped onto the stage and crashed my head into concrete and landed on my hands and knees, jumped up and said, “Happy to be here.” I am bonded to those people by singularity, the only time a performer leaped up into the ceiling. Houdini did other things but never that.

But for every great leap into the ceiling, there are a dozen mistakes. A busy life is full of them. Whenever I go to Carnegie Hall, I remember the show I did there where I sang the New Orleans funeral march, “Just a Little While to Stay Here” and went parading into the house, waving a red umbrella, expecting the audience to sing along and they were embarrassed for me and averted their eyes. They wanted me to be funny, not do a charade of Mardi Gras in the French Quarter. I think about that night with sharp pain. “Forget about it,” you say, I wish I could.

I’ve written some dull, pretentious material—like this sentence here— and that’s why I never sit and read old work. I recently came across a folder from 1976, pages of single-spaced typing, that begins: I am leaving this dark rattan Orlon Saran wrap wingtip apartment and this wickerbasket demitasse wingback risotto kitty litter life and mindless warp of numerals flashing twelve o’clock to go bopbopbop at the wheel of a big old fishtail car screaming west out of this catatonic cocktail freak show scene of Modigliani women with American Express eyes and collagen hearts and pituitaries like shotgun shells and it goes on and on.

I regret that at the end of the last broadcast, July 1, 2016, I did not bring the Prairie Home staff out on stage at the Hollywood Bowl for a bow, the loyal veterans who’d kept the show running all those years, Deb and Kay and Theresa, Jennifer, Tony, Todd, Jason, Olivia, David and Noah and Tom and Alan, Janis, Ben, Ella, Kathryn, Albert, Sam, Thomas, and their leader Kate, and acknowledge them so they could hear the crowd roar. Why did this not occur to me to cue the staff for a bow? So simple. I forgot to do it, the man in the suit.

And most of all I grieve for the death the next spring of my grandson Frederick, seventeen, a funny boy of bottomless curiosity whose mind soaked up reams of information about cars, bugs, animals, India and China, the human environment, and unlike any Keillor I’ve known, he loved to talk, talk, talk. He had a compassion for all other creatures. He landed his first fish and then tried to revive it. A roomful of people in shock gathered for the memorial. I sat behind his brother, Charlie, and his mother, Tiffany, and his grandmother Julie. All I felt was a great heaviness, no tears, just shock. It simply wasn’t possible to imagine Freddy absent from the world. I stood up with Bob and Adam and we sang “Calling My Children Home” and sat down. We all lose our parents, but losing a child is simply not supposed to happen. The brain goes numb, God’s way of offering mercy. If we were fully cognizant, it would be unbearable.

Frederick, 6, and his cat Loretta.