2

Who Commits Fraud and Why: The Profile and Psychology of the Fraudster

According to a 2012 FBI Pittsburgh Division press release, Patricia K. Smith, 57 at the time and the former controller at Baierl Acura, plead guilty in federal court. The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette alleges that Ms. Smith fraudulently transferred $10.3 million from Baierl Acura’s accounts to her own, using the money to finance a spree of frivolity and generosity. Ms. Smith was a one-time trusted employee who worked at the car dealership beginning in 1993, serving as the financial controller and working at the dealership for 11 years before embarking on her bad acts.

According to these sources, from late 2004 through mid-2011, Ms. Smith padded her $53,000-a-year salary with upward of $25,000 a week that she embezzled. What did she do with this extra money: She spent “$43,000 for a hotel in Paris, France, $1.8 million billed to her American Express account for private jet fare … $62,500 for six club-level Super Bowl tickets, and it goes on and on and on.” Apparently a religious woman, she splurged on “The Vatican Package,” ($5,000) which included Mass in Papal Audience with VIP seating, airfare for four, VIP tour of the Vatican Museum with a private tour guide, and a private tour of the Sistine Chapel with family before it is open to the public.

Ms. Smith told U.S. District Judge Gustave Diamond at her sentencing hearing that she spent the money on friends and family, saying “I wanted to earn their love, and I wanted to see what happiness really looked like.”1

What causes a seemingly “good person” (at least before the revelation of their crimes) to commit bad acts? In this chapter, we examine “who commits fraud” and offer some insight into “why.”

The authors examine this topic across several modules. Those modules, along with the learning objectives, include the following:

- Module 1 examines criminology, the study of crime and criminals, and its interface with fraud, financial crimes, and forensic accounting issues. The objective is for the reader to be able to describe occupational fraud and abuse as well as the role of civil litigation in forensic accounting and fraud examination issues.

- Module 2 develops a profile of the garden variety fraudster using one of the most recognized tools in the antifraud community, the fraud triangle. The goal in this module is for the reader to apply the elements of the fraud triangle: nonshareable pressure, perceived opportunity, and rationalization to specific cases.

- Module 3 takes a look at some of the early efforts to fine-tune and improve the fraud triangle, adding the roles of personal integrity, capability, gender, and the influence of the organization. The goal here is for the reader to be able to describe the reasoning behind perpetrator decisions to commit bad acts.

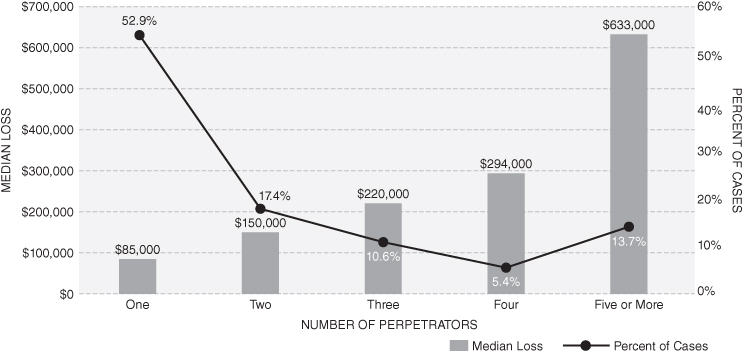

- Module 4 reviews more recent findings from research that considers fraudsters whose profile is inconsistent with the fraud triangle: M.I.C.E., predatory (repeat) fraudsters, and collusive groups. The take-away from this module will be the ability to adjust the assessment of case issues, given the possibility of repeater offenders or collusive fraud teams. When complexity increases, particularly the ability to conceal bad acts, frauds become more difficult to detect and investigate.

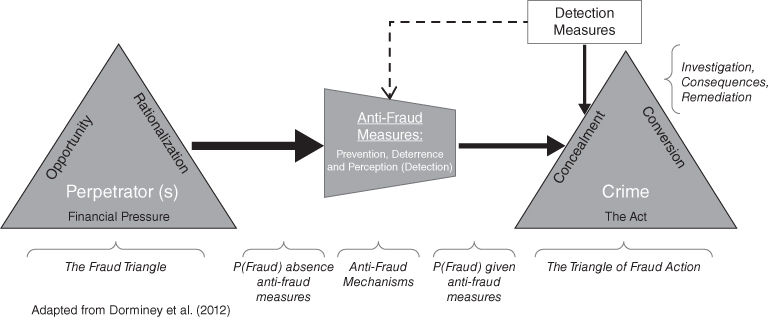

- Module 5 offers a cautionary tale for practicing forensic accountants and fraud examiners related to courtroom testimony grounded in the fraud triangle. It offers a meta-model for moving from a focus on the perpetrator to an investigation grounded in evidence by using the triangle of fraud action (the “elements of fraud”). The important goal here is for the reader to recognize that while the fraud triangle and its improvements across time help us understand who commits fraud and why, when we conduct fraud and forensic examinations, gathering persuasive evidence is the key to success.

Module 1: Criminology, Fraud, and Forensic Accounting

Bethany holds the position of office manager at a small commercial real-estate company. Jackson Stetson, the owner, conducts numerous entertainment events each month to interact with, and locate, new clients. In addition, Mr. Stetson prides himself on his support of charitable organizations. In his capacity as a leader, organizer, and board member of several high-profile charities, Jackson has additional charity events each month.

Bethany is a trusted assistant to Mr. Stetson, runs many aspects of the company and organizes and hosts many of the social events for Mr. Stetson. Bethany has been with the company for many years and has a company credit card to pay for social events and incidentals associated with these events. The company pays the monthly credit card balance; and Bethany is supposed to save receipts and match those receipts to her company credit cards before seeking Mr. Stetson’s approval for company payment.

Initially, Bethany lost a few receipts, and Mr. Stetson waived the requirement that she provide all receipts. As the business grew, Bethany’s schedule became “crazy,” and she had less time for administrative responsibilities. Mr. Stetson was so happy with her work on his social events that he was willing to overlook her lack of attention to administrative details. The problem was that, over time, Bethany started to charge personal expenses on the company-paid credit card. Not only was the company paying Bethany’s salary, they also paid her grocery bills and household expenses at retailers where she shopped for social event incidentals. Over a twenty-four-month period, Bethany was able to double her $80,000 annual take-home pay, and the additional income was tax-free! Eventually, Bethany was caught, convicted, and received a bill from the Internal Revenue Service for back taxes, interest, and penalties.

Criminology

Criminology is the sociological study of crime and criminals. Understanding the nature, dynamics, and scope of fraud and financial crimes is an important aspect of an entry-level professional’s knowledge base. Fraudsters often look exactly like us, and many are first-time offenders. As such, to understand the causes of white-collar crime, we focus on perpetrators of fraud.2

Before talking about crime, it is prudent to consider why the vast majority of people do not commit crime. A number of theories have been put forth but essentially, people obey laws for the following reasons:

- Fear of punishment

- Desire for rewards

- To act in a just and moral manner according to society’s standards

Most civilized societies are dependent upon people doing the right thing. Despite rewards, punishment, and deterrence, the resources required to fully enforce all laws against every violation would be prohibitively expensive. Prevention is impossible, and even deterrence is costly to implement and does not guarantee an adequate level of compliance. The bottom line is that, in general, a person’s normative values of right and wrong dictate their behavior and determine compliance or noncompliance with the law.3 In other words, in most cases, people choose to follow the law because it is the right thing to do. Further, people usually follow laws with which they agree. For example, if the speed limit on a highway is 50 miles per hour, it is likely that some drivers will exceed that limit unless they understand and agree with the reason for it.

Occupational Fraud and Abuse

Occupational fraud and abuse is defined as “the use of one’s occupation for personal enrichment through the deliberate misuse or misapplication of the employing organization’s resources or assets.”4 By the breadth of this definition, occupational fraud and abuse involves a wide variety of conduct by executives, employees, managers, and principals of organizations, ranging from sophisticated investment swindles to petty theft. Common violations include asset misappropriation, fraudulent statements, corruption, pilferage, petty theft, false overtime, using company property for personal benefit, fictitious payroll, and sick time abuses, to name just a few.

Four common elements to these schemes were first identified by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners in its 1996 Report to the Nation on Occupational Fraud and Abuse (Section 3, p. 3), which stated: “The key is that the activity (1) is clandestine, (2) violates the employee’s fiduciary duties to the organization, (3) is committed for the purpose of direct or indirect financial benefit to the employee, and (4) costs the employing organization assets, revenues, or reserves.”

Employee in the context of this definition is any person who receives regular and periodic compensation from an organization for his or her labor. The employee moniker is not restricted to the rank and file, but specifically includes corporate executives, company presidents, top and middle managers, and other workers.

White-Collar Crime

The term white-collar crime was a designation coined by Edwin H. Sutherland in 1939, when he provided the following definition: crime in the upper, white-collar class, which is composed of respectable, or at least respected, business and professional men. White-collar crime is often used interchangeably with occupational fraud and economic crime. While white-collar crime is consistent with the notion of trust violator and is typically associated with an abuse of power, one difficulty with relying on white-collar crime as a moniker for financial and economic crimes is that many criminal acts such as murder, drug trafficking, burglary, and theft are motivated by money. Furthermore, the definition, though broad, leaves out the possibility of the perpetrator being an organization where the victim is often the government and society (e.g., tax evasion and fixed contract bidding). Nevertheless, the term white-collar crime captures the essence of the type of perpetrator that one finds at the heart of occupational fraud and abuse.

Organizational Crime

Organizational crime occurs when entities, companies, corporations, not-for-profits, nonprofits, and government bodies, otherwise legitimate and law-abiding organizations, are involved in a criminal offense. In addition, individual organizations can be trust violators when the illegal activities of the organization are reviewed and approved by persons with high standing in an organization, such as board members, executives, and managers. Federal law allows organizations to be prosecuted in a manner similar to individuals.5 For example, although professional services firm Arthur Andersen’s 2002 conviction of obstruction of justice associated with the Enron fraud was later overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court, the conviction, a felony offense, prevented it from auditing public companies. Corporate violations may include administrative breaches, such as noncompliance with agency, regulatory, and court requirements; environmental infringements; fraud and financial crimes, such as financial reporting fraud, bribery, and illegal kickbacks; labor abuses; manufacturing infractions related to public safety and health; and unfair trade practices.

Organizational crime is more of a problem internationally and often consists of unfair pricing, unfair business practices, violation of the FCPA (Foreign Corrupt Practices Act), and tax evasion. Organizations are governed by a complex set of interactions among boards of directors, audit committees, executives, and managers. In addition, the actions of external stakeholders such as auditors and regulators impact the governance of organizations. As such, it is often difficult to distinguish between those individuals with responsibility for compliance with particular laws and regulations and those infractions committed by the organization. In addition, when considerable financial harm has been inflicted on society as a result of corporate wrongdoing, the organization is often an attractive target because of its deep pockets with which to pay fines and restitution.

It is more common for corporations to become embroiled in legal battles that wind up in civil court. Such litigation runs the gamut of forensic litigation advisory services offered by forensic accountants, including damage claims made by plaintiffs and defendants; workplace issues such as lost wages, disability, and wrongful death; assets and business valuations; costs and lost profits associated with construction delays or business interruptions; insurance claims; fraud; antitrust actions; intellectual property infringement; environmental issues; tax claims; or other disputes. If you open any 10-K or annual report, you will likely find mention of pending lawsuits in the notes to the financial statements. Furthermore, these filings include only those lawsuits deemed to be “material” as defined by accounting standards. Most corporations are involved in numerous lawsuits considered to be below the auditor’s materiality threshold.

Organized Crime

These crimes are often complex, involving many individuals, organizations, and shell companies, and often cross jurisdictional borders. In this context, fraud examiners and financial forensic professionals often think of terrorist financing, the mob, international hacking, cyber-crime, and drug trafficking. Some of the crimes typically associated with organized crime include money laundering, mail and wire fraud, conspiracy, and racketeering.

Money laundering addresses the means by which organized criminals take money from illegal sources and process it so that it appears “as if” it came from legitimate business sources.

Mail and wire fraud involves schemes that use the postal service or interstate wires, such as telephone calls, email, or other electronic communications, to execute the fraud. The crimes of mail and wire fraud are often used by prosecutors to charge bad actors when other criminal charges are difficult to prove.

Criminal conspiracy occurs when two or more people intend to commit an illegal act and take some steps toward its implementation. A charge of conspiracy is often used as a means of prosecuting individuals involved in illegal organized activity. For example, if Alan, Bob, and Chad plan to rob a bank, and then research the bank’s security system, and purchase a gun to implement their plan, they could be charged with criminal conspiracy to commit robbery, even if they don’t go through with their plan.

RICO (Racketeering Influence and Corrupt Organizations Act) addresses organizations involved in criminal activity. For example, portions of the RICO Act

- outlaw investing illegal funds in another business;

- outlaw acquisition of a business through illegal acts;

- outlaw the conduct of business affairs with funds derived from illegal acts.

Torts, Breach of Duty, and Civil Litigation

Black’s Law Dictionary defines “tort” as “a private or civil wrong or injury, other than breach of contract, for which the law will provide a remedy in the form of an action for damages.” When a tort is committed, the party who was injured is entitled to collect compensation for damages from the wrongdoer for that private wrong.6 The tort of contract interference or tortuous interference with contracts occurs when parties are not allowed the freedom to contract without interference from third parties. While the elements of tortuous interference are complex, a basic definition is that the law affords a remedy when someone intentionally persuades another to break a contract already in existence with a third party.7

Another tort—negligence—applies when the conduct of one party did not live up to minimal standards of care. Each person has a duty to act in a reasonable and prudent manner. When individuals or entities fail to live up to this standard, they are considered “negligent.” The legal standard for negligence has five elements8:

- Duty—a duty to act exists between the parties

- Breach—a determination that the defendant failed to use ordinary or reasonable care in the exercise of that duty

- Cause in Fact—an actual connection between the defendant’s breach of duty and the plaintiff’s harm can be established

- Proximate Cause—the defendant must have been the proximate cause or contributed to the injury to the plaintiff

- Damages—the plaintiff must establish that damages resulted from the defendant’s breach of duty. In order to win an award for damages, the injured party must generally prove two points:

- The other party was liable for all or part of the damages claimed

- The injured party suffered damages as the result of the actions, or lack thereof, of the offending party

Furthermore, the amount of damages must be proven with a reasonable degree of certainty as to the amount claimed, and that the defendant could reasonably foresee the likelihood of damages if they failed to meet their obligations. The focus on monetary damages often creates professional opportunities for forensic accountants to work for plaintiffs or defendants. Generally speaking, the threshold is fairly low for a person or organization to sue another in civil court for a tort, breach of contract, or negligence. While judges have the ability to issue summary judgments and dismiss frivolous lawsuits, most judges are more inclined to let the parties negotiate a settlement or let a jury decide the case based on the merits of the arguments and evidence put forth by the plaintiff and the defense. A critical aspect of civil litigation for the forensic accountant and fraud examiner is the understanding that both sides (plaintiff and defendant) are expected to tell their “story.” The professional’s role is to examine those competing and conflicting stories to see which one, or which elements of each side’s story, is consistent with the story being told by the other relevant evidence. It also requires a thorough examination of monetary damage claims, in light of the evidence, particularly how those damage amount(s) relate to the various stories presented by the opposing sides in civil litigation.

Module 2: Who Commits Fraud and Why: The Fraud Triangle

Fraudsters, by their very nature, are trust violators. Perpetrators, generally, have achieved a position of trust within an organization and have chosen to violate that trust. According to the ACFE, owners and executives are involved in only about one quarter of all occupational frauds but, when involved, steal significantly larger amounts than lower-level employees. Managers are the second most frequent perpetrators. Finally, line employees are the principal perpetrators in the majority of occupational fraud schemes, yielding average losses to the company of less than $100,000. Research suggests that although males are most frequently the perpetrators, women are the principal perpetrators in approximately 30%–35% of all cases. Fraudsters are found in all age categories and educational achievement levels, but victim losses rise with both the age and education of the principal perpetrator. In the majority of cases, a perpetrator acts alone; however, when fraudsters collude, the losses to the victim organization increase more than fourfold. The following profile summarizes the characteristics of the typical fraud perpetrator.

| Fraud perpetrator profile | |

| Male9 | Well educated |

| Middle aged to retired | Accountant, upper management, or executive |

| With the company for five or more years | Acts alone |

| Never charged or convicted of a criminal offense | |

Regardless of whether fraud perpetrators are male or female, the fraudster’s profile tends to look like those of average persons. Perhaps the most interesting of all the characteristics listed is that fraudsters typically do not have a criminal background.10 Furthermore, it is not uncommon for a fraud perpetrator to be a respected member of the community, attend church services, and have a family.

Interestingly, in over 90 percent of the fraud cases examined by the ACFE, the perpetrator had been with the victim organization for more than one year. Dr. W. Steve Albrecht, a pioneer researcher, notes: “Just because someone has been honest for 10 years doesn’t mean that they will always be honest.” Not surprisingly, the longer the tenure, the larger the average loss. In less than 15% of fraud cases examined did the perpetrator have any prior criminal history. In fact, the typical fraudster is not a pathological criminal, but rather, a seemingly “good person” who has achieved a position of trust. So the critical question remains: what causes good people to make bad choices?

Edwin H. Sutherland

Much of the early literature regarding who commits fraud and why is based upon the works of Edwin H. Sutherland (1883–1950), a criminologist. For those new to the antifraud profession, Sutherland is to the world of white-collar crime, what Freud is to psychology. Indeed, it was Sutherland who coined the term white-collar crime in 1939. He intended the definition to mean criminal acts of corporations and individuals acting in their professional capacity. Since that time, however, the term has come to mean almost any financial or economic crime, from the mailroom to the boardroom.

Sutherland was particularly interested in fraud committed by the elite upper-world business executive, either against shareholders or the public. As Gilbert Geis noted, Sutherland said, “General Motors does not have an inferiority complex, United States Steel does not suffer from an unresolved Oedipus problem, and the DuPonts do not desire to return to the womb. The assumption that an offender may have such pathological distortions of the intellect or the emotions seems to me absurd, and if it is absurd regarding the crimes of businessmen, it is equally absurd regarding the crimes of persons in the economic lower classes.”11

Many criminologists believe that Sutherland’s most important contribution to criminal literature was elsewhere. Later in his career, he developed the theory of differential association, which is now the most widely accepted theory of criminal behavior in the twentieth century. Until Sutherland’s landmark work in the 1930s, most criminologists and sociologists held the view that crime was genetically based, that criminals beget criminal offspring. Sutherland was able to explain crime’s environmental considerations through the theory of differential association. The theory’s basic tenet is that crime is learned, much like we learn math, English, or guitar playing.12

Sutherland believed this learning of criminal behavior occurred with other persons in a process of communication. Therefore, he reasoned, criminality cannot occur without the assistance of other people. Sutherland further theorized that the learning of criminal activity usually occurred within intimate personal groups. This explains, in his view, how a dysfunctional parent is more likely to produce dysfunctional offspring. Sutherland believed that the learning process involved two specific areas: the techniques to commit the crime; and the attitudes, drives, rationalizations, and motives of the criminal mind. You can see how Sutherland’s differential association theory fits with occupational offenders. Organizations that have dishonest employees will eventually infect a portion of honest ones. It also goes the other way: honest employees will eventually have an influence on some of those who are dishonest.

Donald R. Cressey and the Fraud Triangle

One of Sutherland’s brightest students during the 1940s was Donald R. Cressey (1919–1987). Although much of Sutherland’s research concentrated on upper-world criminality, Cressey took his own studies in a different direction. Working on his Ph.D. in criminology, he decided his dissertation would concentrate on embezzlers. To serve as a basis for his research, Cressey interviewed about 200 incarcerated inmates at prisons in the Midwest.

Cressey’s Hypothesis

Embezzlers, whom he called “trust violators,” intrigued Cressey. He was especially interested in the circumstances that led them to be overcome by temptation. For that reason, he excluded from his research those employees who took their jobs for the purpose of stealing—a relatively minor number of offenders at that time. Upon completion of his interviews, he developed what still remains as the classic model for the occupational offender. His research was published in Other People’s Money: A Study in the Social Psychology of Embezzlement.

Cressey’s final hypothesis read as follows:

Trusted persons become trust violators when they conceive of themselves as having a financial problem that is nonshareable, are aware this problem can be secretly resolved by violation of the position of financial trust, and are able to apply to their own conduct in that situation verbalizations which enable them to adjust their conceptions of themselves as trusted persons with their conceptions of themselves as users of the entrusted funds or property.13

In a 1991 article penned by Dr. Steve Albrecht, he organized Cressey’s three conditions into a tool that has become known as the “fraud triangle” (Figure 2-1).14 One leg of the triangle represents perceived pressure. The second leg is perceived opportunity, and the final leg denotes rationalization.

FIGURE 2-1 Fraud triangle

Nonshareable Financial Pressures

The role of perceived nonshareable financial pressures is important. Cressey reported that when the trust violators were asked to explain why they refrained from violation of other positions of trust they might have held at previous times, or why they had not violated the subject position at an earlier time, those who had an opinion expressed the equivalent of one or more of the following quotations: (a) “There was no need for it like there was this time.” (b) “The idea never entered my head.” (c) “I thought it was dishonest then, but this time it did not seem dishonest at first.”15 “In all cases of trust violation encountered, the violator considered that a financial problem which confronted him could not be shared with persons who, from a more objective point of view, probably could have aided in the solution of the problem.”16

What is considered nonshareable is, of course, wholly in the eyes of the potential occupational offender, as Cressey noted:

Thus a man could lose considerable money at the racetrack daily, but the loss, even if it construed a problem for the individual, might not constitute a nonshareable problem for him. Another man might define the problem as one that must be kept secret and private. Similarly, a failing bank or business might be considered by one person as presenting problems which must be shared with business associates and members of the community, while another person might conceive these problems as nonshareable.17

In addition to being nonshareable, the problem that drives the fraudster is described as “financial” because these are the types of problems that can generally be solved by the theft of cash or other assets. A person with large gambling debts, for instance, would need cash to pay those debts. Cressey noted, however, that there are some nonfinancial problems that could be solved by misappropriating funds through a violation of trust. For example, a person who embezzles in order to get revenge on her employer for perceived “unfair” treatment uses financial means to solve what is essentially a nonfinancial problem.18

Through his research, Cressey also found that the nonshareable problems encountered by the people he interviewed arose from situations that could be divided into six basic categories:

- Violation of ascribed obligations

- Problems resulting from personal failure

- Business reversals

- Physical isolation

- Status gaining

- Employer–employee relations

All these situations dealt in some way with status-seeking or status-maintaining activities by the subjects.19 In other words, the nonshareable problems threatened the status of the subjects, or threatened to prevent them from achieving a higher status than the one they occupied at the time of their violation.

Violations of Ascribed Obligations

Violation of ascribed obligations has historically proved to be a strong motivator of financial crimes. Cressey explains in this way:

Financial problems incurred through nonfinancial violations of positions of trust often are considered as nonshareable by trusted persons since they represent a threat to the status which holding the position entails. Most individuals in positions of financial trust, and most employers of such individuals, consider that incumbency in such a position necessarily implies that, in addition to being honest, they should behave in certain ways and should refrain from participation in some other kinds of behavior.20

In other words, the mere fact that a person has a trusted position carries with it the implied duty to act in a manner becoming his status. Persons in trusted positions may feel they are expected to avoid conduct such as gambling, drinking, drug use, or other activities that are considered seamy and undignified.

When these persons then fall into debt or incur large financial obligations as a result of conduct that is “beneath” them, they feel unable to share the problem with their peers because this would require admitting that they have engaged in the dishonorable conduct that lies at the heart of their financial difficulties. Basically, by admitting that they had lost money through some disreputable act, they would be admitting—at least in their own minds—that they are unworthy to hold their trusted positions.

Problems Resulting from Personal Failure

Problems resulting from personal failures, Cressey writes, are those that the trusted person feels he caused through bad judgment and therefore feels personally responsible for. Cressey cites one case in which an attorney lost his life’s savings in a secret business venture. The business had been set up to compete with some of the attorney’s clients, and though he thought his clients probably would have offered him help if they had known what dire straits he was in, he could not bring himself to tell them that he had secretly tried to compete with them. He also was unable to tell his wife that he’d squandered their savings. Instead, he sought to alleviate the problem by embezzling funds to cover his losses.21

While some pressing financial problems may be considered as having resulted from “economic conditions,” “fate,” or some other impersonal force, others are considered to have been created by the misguided or poorly planned activities of the individual trusted person. Because he fears a loss of status, the individual is afraid to admit to anyone who could alleviate the situation the fact that he has a problem which is a consequence of his “own bad judgment” or “own fault” or “own stupidity.”22 In short, pride goeth before the fall.23 If the potential offender has a choice between covering his poor investment choices through a violation of trust and admitting that he is an unsophisticated investor, it is easy to see how some prideful people’s judgment could be clouded.

Business Reversals

Business reversals were the third type of situation Cressey identified as leading to the perception of nonshareable financial problems. This category differs from the class of “personal failures” described above because here the trust violators tend to see their problems as arising from conditions beyond their control: inflation, high interest rates, economic downturns, etc. In other words, these problems are not caused by the subject’s own failings, but instead by outside forces.

Cressey quoted the remarks of one businessman who borrowed money from a bank using fictitious collateral:

Case 36. There are very few people who are able to walk away from a failing business. When the bridge is falling, almost everyone will run for a piece of timber. In business there is this eternal optimism that things will get better tomorrow. We get to working on the business, keeping it going, and we get almost mesmerized by it … Most of us don’t know when to quit, when to say, ‘This one has me licked. Here’s one for the opposition.’24

It is interesting to note that even in situations where the problem is perceived to be out of the trusted person’s control, the issue of status still plays a big role in that person’s decision to keep the problem a secret. The subject of Case 36 continued, “If I’d have walked away and let them all say, ‘Well, he wasn’t a success as a manager, he was a failure,’ and took a job as a bookkeeper, or gone on the farm, I would have been all right. But I didn’t want to do that.”25 The desire to maintain the appearance of success was a common theme in the cases involving business reversals.

Physical Isolation

The fourth category Cressey identified consisted of problems resulting from physical isolation. In these situations, the trusted person simply has no one to turn to. It’s not that he is afraid to share his problem; it’s that he has no one to share the problem with. He is in a situation where he does not have access to trusted friends or associates who would otherwise be able to help him. Cressey cited the subject of Case 106 in his study, a man who found himself in financial trouble after his wife had died. In her absence, he had no one to go to for help and he wound up trying to solve his problem through an embezzlement scheme.26

Status Gaining

The fifth category involves problems relating to status gaining, which is a sort of extreme example of “keeping up with the Joneses” syndrome. In the categories that have been discussed previously, the offenders were generally concerned with maintaining their status (i.e., not admitting to failure, keeping up appearance of trustworthiness), but here the offenders are motivated by a desire to improve their status. The motive for this type of conduct is often referred to as “living beyond one’s means” or “lavish spending,” but Cressey felt that these explanations did not get to the heart of the matter. The question was: what made the desire to improve one’s status nonshareable? He noted,

The structuring of status ambitions as being nonshareable is not uncommon in our culture, and it again must be emphasized that the structuring of a situation as nonshareable is not alone the cause of trust violation. More specifically, in this type of case a problem appears when the individual realizes that he does not have the financial means necessary for continued association with persons on a desired status level, and this problem becomes nonshareable when he feels that he can neither renounce his aspirations for membership in the desired group nor obtain prestige symbols necessary to such membership.27

In other words, it is not the desire for a better lifestyle that creates the nonshareable problem (we all want a better lifestyle), rather it is the inability to obtain the finer things through legitimate means, and at the same time, an unwillingness to settle for a lower status that creates the motivation for trust violation.

Employer–Employee Relations

Finally, Cressey described problems resulting from employer–employee relationships. The most common, he stated, was an employed person who resents his status within the organization in which he is trusted and at the same time feels he has no choice but to continue working for the organization. The resentment can come from perceived economic inequities, such as pay, or from the feeling of being overworked or underappreciated. Cressey said this problem becomes nonshareable when the individual believes that making suggestions to alleviate his perceived maltreatment will possibly threaten his status in the organization.28 There is also a strong motivator for the perceived employee to want to “get even” when he feels ill-treated.

The Importance of Solving the Problem in Secret

Given that Cressey’s study was done in the early 1950s, the workforce was obviously different from today. But the employee faced with an immediate, nonshareable financial need hasn’t changed much over the years. That employee is still placed in the position of having to find a way to relieve the pressure that bears down upon him. Simply stealing money, however, is not enough; Cressey found it was crucial that the employee be able to resolve the financial problem in secret. As we have seen, the nonshareable financial problems identified by Cressey all dealt in some way with questions of status; the trust violators were afraid of losing the approval of those around them and so were unable to tell others about the financial problems they encountered. If they could not share the fact that they were under financial pressure, it follows that they would not be able to share the fact that they were resorting to illegal means to relieve that pressure. To do so would be to admit the problems existed in the first place.

The interesting thing to note is that it is not the embezzlement itself that creates the need for secrecy in the perpetrator’s mind; it is the circumstances that led to the embezzlement (e.g., a violation of ascribed obligation, a business reversal). Cressey pointed out,

In all cases [in the study] there was a distinct feeling that, because of activity prior to the defalcation, the approval of groups important to the trusted person had been lost, or a distinct feeling that present group approval would be lost if certain activity were revealed [the nonshareable financial problem], with the result that the trusted person was effectively isolated from persons who could assist him in solving problems arising from that activity29 (emphasis added).

Perceived Pressure

Many people inside any organizational structure have at least some access to cash, checks, or other assets. However, according to Cressey’s hypothesis, it is a perceived pressure that causes individuals to seriously consider availing themselves of the opportunity presented by, for example, an internal control weakness. In today’s terms, fraud pressures can arise from financial problems, such as living beyond one’s means, greed, high debt, poor credit, family medical bills, investment losses, or children’s educational expenses. Pressures may also arise from vices, such as gambling, drugs, or an extramarital affair.

Financial statement fraud is often attributed to pressures, such as meeting analysts’ expectations, deadlines, and cutoffs, or qualifying for bonuses. Finally, pressure may be the mere challenge of getting away with it or keeping up with family and friends. The word perceived is carefully chosen here. Individuals react differently to certain stimuli, and pressures that have no impact on one person’s choices may dramatically affect another’s. It is important that the fraud examiner or forensic accountant investigating a case recognize this facet of human nature.

Even in civil litigation, pressure can cause one organization to violate the terms and conditions of a contract. For example, a company may not be able to complete a construction project on time. As such, they may take “shortcuts” in violation of contract terms due to the pressure of an impending deadline. In other cases, an organization is attempting to raise investment capital; so, company leadership might “juice” (increase) the valuation for which they claim the business is worth.

Unanticipated pressures from a variety of sources may sometimes cause a person to act in inappropriate ways. It is also inherent upon the professional to realize that the majority of persons facing these same pressures do not commit fraud or financial crimes, but rather find some alternative, nonnefarious means of relieving the pressure.

Perceived Opportunity

According to the fraud triangle model, the presence of a nonshareable financial problem by itself will not lead an employee to commit fraud. The key to understanding Cressey’s theory is to remember that all three elements must be present for a trust violation to occur. The nonshareable financial problem creates the motive for the crime to be committed, but the employee must also perceive that he has an opportunity to commit the crime without being caught. This perceived opportunity constitutes the second element.

In Cressey’s view, there were two components of the perceived opportunity to commit a trust violation: general information and technical skill. General information is simply the knowledge that the employee’s position of trust could be violated. This knowledge might come from hearing of other embezzlements, from seeing dishonest behavior by other employees, or just from generally being aware of the fact that the employee is in a position where he could take advantage of his employer’s faith in him. Technical skill refers to the abilities needed to commit the violation. These are usually the same abilities that the employee needs to have to obtain and keep his position in the first place. Cressey noted that most embezzlers adhere to their occupational routines (and their job skills) in order to perpetrate their crimes.30

In essence, the perpetrator’s job will tend to define the type of fraud he has the opportunity to commit. “Accountants use checks which they have been entrusted to dispose of, sales clerks withhold receipts, bankers manipulate seldom-used accounts or withhold deposits, real estate fraudsters use deposits entrusted to them, and so on.”31 Obviously, the general information and technical skill that Cressey identified are not unique to occupational offenders; most, if not all, employees have these same characteristics. But because trusted persons possess this information and skill, when they face a nonshareable financial problem they see it as something that they have the power to correct. They apply their understanding of the possibility for trust violation to the specific crises they are faced with.

Cressey observed, “It is the next step which is significant to violation: the application of the general information to the specific situation, and conjointly, the perception of the fact that in addition to having general possibilities for violation, a specific position of trust can be used for the specific purpose of solving a nonshareable problem.”32

Whether the issue pertains to managers overriding internal controls related to financial statement fraud or a breakdown in the internal control environment that allows the accounts receivable clerk to abscond with the cash and checks of a business, the perpetrators need the opportunity to commit and conceal their fraud. Furthermore, when it comes to fraud prevention and deterrence, most accountants and antifraud professionals tend to direct significant efforts toward minimizing opportunity through the internal control environment. However, internal controls are just one element of opportunity. Other integral ways to reduce opportunity include providing adequate training and supervision of personnel; effective monitoring of company management by auditors, audit committees, and boards of directors; proactive antifraud programs; a strong ethical culture; anonymous hotlines; and whistleblower protections.

Fraud deterrence begins in the employee’s mind. Employees who perceive that they will be caught are less likely to engage in fraudulent conduct. The logic is hard to dispute. Exactly how much deterrent effect this concept provides depends on a number of factors, both internal and external. But internal controls can have a deterrent effect only when the employee perceives that such a control exists in both design and operation, and the controls are likely to uncover the potential fraud. This is referred to as the “perception of detection,” and it is a critical aspect of antifraud efforts. Alternatively stated, “hidden” controls have little deterrent effect. Conversely, controls that are not even in place—but are perceived to be—may have deterrent value.

According to the 2016 ACFE Report to the Nations (see Figure 2-2), the general implementation rates of antifraud controls have remained notably consistent throughout their studies, although the ACFE has seen a slight uptick in the prevalence of each control over the last six years. The most notable changes have been in the implementation rates of hotlines and fraud training for employees, which have increased approximately 9% and 8%, respectively, since 2010. On the other end of the spectrum, the percentage of organizations that undergo external audits of their financial statements has remained relatively flat, with less than a 1% increase over the same period.

| Control | 2010 Implementation rate | 2016 Implementation rate | Change from 2010–2016 |

| Hotline | 51.2% | 60.1% | 8.9% |

| Fraud Training for Employees | 44.0% | 51.6% | 7.6% |

| Anti-fraud Policy | 42.8% | 49.6% | 6.8% |

| Code of Conduct | 74.8% | 81.1% | 6.3% |

| Management Review | 58.8% | 64.7% | 5.9% |

| Surprise Audits | 32.3% | 37.8% | 5.6% |

| Fraud Training for Managers/Executives | 46.2% | 51.3% | 5.2% |

| Independent Audit Committee | 58.4% | 62.5% | 4.1% |

| Management Certification of Financial Statements | 67.9% | 71.9% | 4.0% |

| Rewards for Whistleblowers | 8.6% | 12.1% | 3.5% |

| Job Rotation/Mandatory Vacation | 16.6% | 19.4% | 2.8% |

| External Audit of Internal Controls over Financial Reporting | 65.4% | 67.6% | 2.2% |

| Employee Support Programs | 54.6% | 56.1% | 1.5% |

| External Audit of Financial Statements | 80.9% | 81.7% | 0.8% |

FIGURE 2-2 Trends in the implementation of antifraud control

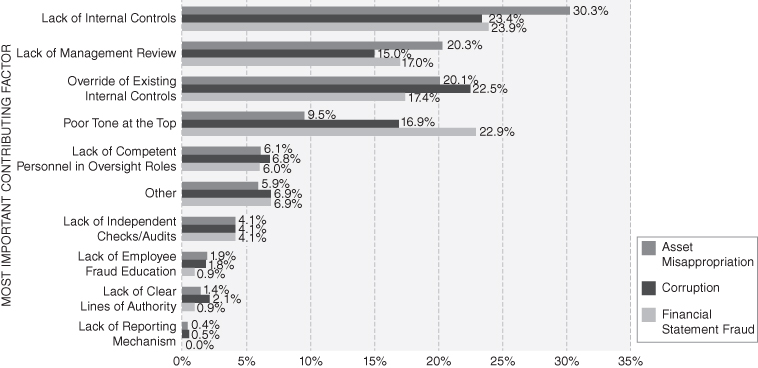

In Figure 2-3, the ACFE examined the impact of internal control weaknesses by the type of fraud scheme perpetrated: asset misappropriation, corruption, and financial statement fraud. The findings suggest that organizations that lacked internal controls were more susceptible to asset misappropriation schemes, while corruption schemes, more often, involved an override of existing controls. Further, poor “tone at the top” was much more likely to contribute to financial statement fraud than either of the other two categories of occupational fraud.

FIGURE 2-3 Internal control weaknesses that contributed to fraud

Rationalizations

The third and final factor in the fraud triangle is rationalization. According to the fraud triangle hypothesis, the characteristic that puts fraudsters over the top is rationalization. How do perpetrators sleep at night or look at themselves in the mirror? The typical fraud perpetrator has no criminal history and has been with the victim company for some length of time. Because they generally are not habitual criminals and are in a position of trust, they must develop a rationalization for their actions to feel justified in their misdeed. Rationalizations may include an employee/manager’s feeling of job dissatisfaction, lack of recognition for a job well done, low compensation, an attitude of “they owe me,” “I’m only borrowing the money,” “nobody is getting hurt,” “they would understand if they knew my situation,” “it’s for a good purpose,” or “everyone else is doing it.”

Cressey pointed out that rationalization is not an ex post facto means of justifying a theft that has already occurred. Significantly, rationalization is a necessary component of the crime before it takes place; in fact, it is a part of the motivation for the crime.33 Because the embezzler does not view himself as a criminal, he must justify his misdeeds before he ever commits them. Rationalization is necessary so that the perpetrator can make his illegal behavior acceptable to him and maintain his concept of himself as a trusted person.34 After the criminal act has taken place, the rationalization will often be abandoned. This reflects the nature of us all: the first time we do something contrary to our morals, it bothers us. As we repeat the act, it becomes easier. One hallmark of occupational fraud and abuse offenders is that once the line is crossed, the illegal acts become more or less continuous. So an occupational fraudster might begin stealing with the thought that “I’ll pay the money back,” but after the initial theft is successful, he will usually continue to steal past the point where there is any realistic possibility of repaying the stolen funds.

Cressey found that the embezzlers he studied, generally, rationalized their crimes by viewing them (1) as essentially noncriminal, (2) as justified, or (3) as part of a general irresponsibility for which they were not completely accountable.35 He also found that the rationalizations used by trust violators tended to be linked to their positions and to the manner in which they committed their violations. He examined this by dividing the subjects of his study into three categories: independent businessmen, long-term violators, and absconders. He discovered that each group had its own type of rationalization.

Independent Businessmen

The independent businessmen in Cressey’s study were persons who were in business for themselves and who converted deposits that had been entrusted to them.36 Perpetrators in this category tended to use one of two common excuses: (1) they were “borrowing” the money they converted or (2) the funds entrusted to them were really theirs—you can’t steal from yourself. Cressey found the “borrowing” rationalization was the most frequently used. These perpetrators also tended to espouse the idea that “everyone” in business misdirects deposits in some way, which therefore made their own misconduct less wrong than stealing.37 Also, the independent businessmen almost universally felt their illegal actions were predicated by an “unusual situation,” which Cressey perceived to be in reality a nonshareable financial problem.

Long-Term Violators

Cressey defined long-term violators as individuals who converted their employer’s funds, or funds belonging to their employer’s clients, by taking relatively small amounts over a period of time.38 Similar to independent businessmen, the long-term violators also generally preferred the “borrowing” rationalization. Other rationalizations of long-term violators were noted, too, but they almost always were used in connection with the “borrowing” theme: (1) they were embezzling to keep their families from shame, disgrace, or poverty; (2) theirs was a case of “necessity”; their employers were cheating them financially; or (3) their employers were dishonest toward others and deserved to be fleeced. Some even pointed out that it was more difficult to return the funds than to steal them in the first place and claimed they did not pay back their “borrowings” because they feared that would lead to detection of their thefts. A few in the study actually kept track of their thefts but most only did so at first. Later, as the embezzlements escalated, it is assumed that the offender would rather not know the extent of his “borrowings.”

All of the long-term violators in the study expressed a feeling that they would like to eventually “clean the slate” and repay their debt. This feeling usually arose even before the perpetrators perceived that they might be caught. Cressey pointed out that at this point, whatever fear the perpetrators felt in relation to their crimes was related to losing their social position by the exposure of their nonshareable problem, not the exposure of the theft itself or the possibility of punishment or imprisonment. This is because their rationalization still prevented them from perceiving their misconduct as criminal. “The trust violator cannot fear the treatment usually accorded criminals until he comes to look upon himself as a criminal.”39

Eventually, most of the long-term violators finally realized they were “in too deep.” It is at this point that the embezzler faces a crisis. While maintaining the borrowing rationalization (or other rationalizations, for that matter), the trust violator is able to maintain his self-image as a law-abiding citizen; but when the level of theft escalates to a certain point, the perpetrator is confronted with the idea that he is behaving in a criminal manner. This is contrary to his personal values and the values of the social groups to which he belongs. This conflict creates a great deal of anxiety for the perpetrator. A number of offenders described themselves as extremely nervous and upset, tense, and unhappy.40

Without the rationalization that they are borrowing, long-term offenders in the study found it difficult to reconcile converting money, at the same time seeing themselves as honest and trustworthy. In this situation, they have two options: (1) they can readopt the attitudes of the (law-abiding) social group that they identified with before the thefts began or (2) they can adopt the attitudes of the new category of persons (criminals) with whom they now identify.41 From his study, Cressey was able to cite examples of each type of behavior. Those who sought to readopt the attitudes of their law-abiding social groups “may report their behavior to the police or to their employer, quit taking funds or resolve to quit taking funds, speculate or gamble wildly in order to regain the amounts taken, or ‘leave the field’ by absconding or committing suicide.”42 On the other hand, those who adopt the attitudes of the group of criminals to which they now belong “may become reckless in their defalcations, taking larger amounts than formerly with fewer attempts to avoid detection and with no notion of repayment.”43

Absconders

The third group of offenders Cressey discussed was absconders—people who take the money and run. Cressey found that the nonshareable problems for absconders usually resulted from physical isolation. He observed that these people “usually are unmarried or separated from their spouses, live in hotels or rooming houses, have few primary group associations of any sort, and own little property. Only one of the absconders interviewed had held a higher status position of trust, such as an accountant, business executive, or bookkeeper.”44 Cressey also found that the absconders tended to have lower occupational and socioeconomic status than the members of the other two categories.

Because absconders tended to lack strong social ties, Cressey found that almost any financial problem could be defined as nonshareable for these persons, and also that rationalizations were easily adopted because the persons only had to sever a minimum of social ties when they absconded.45 The absconders rationalized their conduct by noting that their attempts to live honest lives had been futile (hence their low status). They also adopted an attitude of not caring what happened to themselves and a belief that they could not help themselves because they were predisposed to criminal behavior. The latter two rationalizations, which were adopted by absconders in Cressey’s study, allowed them to remove almost all personal accountability from their conduct.46

In the 1950s, when Cressey gathered this data, embezzlers were considered persons of higher socioeconomic status who took funds over a limited period of time because of some personal problem such as drinking or gambling, while “thieves” were considered persons of lower status who took whatever funds were at hand. Cressey noted,

Since most absconders identify with the lower status group, they look upon themselves as belonging to a special class of thieves rather than trust violators. Just as long-term violators and independent businessmen do not at first consider the possibility of absconding with the funds, absconders do not consider the possibility of taking relatively small amounts of money over a period of time.47

The theory of rationalization, however, has its skeptics. Although it is difficult to know for certain the thought process of a perpetrator, we can consider the following example. Let’s say that the speed limit is sixty-five miles per hour, but I put my cruise control on seventy or seventy-five to keep up with the other lawbreakers. Do I consciously think to myself, “I’m breaking the law, so what is my excuse, my rationalization, if I am stopped for speeding by a police officer?” Most people don’t think about that until the flashing lights appear in their rearview mirror. Is the thought process of a white-collar criminal really different from that of anyone else?

Conjuncture of Events

One of the most fundamental observations of the Cressey study was that it took all three elements—perceived nonshareable financial problem, perceived opportunity, and the ability to rationalize—for the trust violation to occur. If any of the three elements were missing, trust violation did not occur.

[a] trust violation takes place when the position of trust is viewed by the trusted person according to culturally provided knowledge about and rationalizations for using the entrusted funds for solving a non- shareable problem, and that the absence of any of these events will preclude violation. The three events make up the conditions under which trust violation occurs and the term “cause” may be applied to their conjecture since trust violation is dependent on that conjuncture. Whenever the conjuncture of events occurs, trust violation results, and if the conjuncture does not take place there is no trust violation.48

Cressey’s Conclusion

Cressey’s classic fraud triangle helps explain the nature of many—but not all—occupational offenders. For example, although academicians have tested his model, it has still not fully found its way into practice in terms of developing fraud prevention programs. Our sense tells us that one model—even Cressey’s—will not fit all situations. Plus, the study is nearly half a century old. There has been considerable social change in the interim. And now, many antifraud professionals believe there is a new breed of occupational offender—those who simply lack a conscience sufficient to overcome temptation. Even Cressey saw the trend later in his life.

After doing this landmark study in embezzlement, Cressey went on to a distinguished academic career, eventually authoring 13 books and nearly 300 articles on criminology. He rose to the position of Professor Emeritus in Criminology at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Joe Wells, Founder and Chairman of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners Remembers Donald Cressey

It was my honor to know Cressey personally. Indeed, he and I collaborated extensively before he died in 1987, and his influence on my own antifraud theories has been significant. Our families are acquainted; we stayed in each other’s homes; we traveled together; he was my friend. In a way, we made the odd couple—he, the academic, and me, the businessman; he, the theoretical, and me, the practical.

I met him as the result of an assignment in about 1983. A Fortune 500 company hired me on an investigative and consulting matter. They had a rather messy case of a high-level vice president who was put in charge of a large construction project for a new company plant. The $75 million budget for which he was responsible proved to be too much of a temptation. Construction companies wined and dined the vice president, eventually providing him with tempting and illegal bait: drugs and women. He bit.

From there, the vice president succumbed to full kickbacks. By the time the dust settled, he had secretly pocketed about $3.5 million. After completing the internal investigation for the company, assembling the documentation and interviews, I worked with prosecutors at the company’s request to put the perpetrator in prison. Then the company came to me with a very simple question: “Why did he do it?” As a former FBI Agent with hundreds of fraud cases under my belt, I must admit I had not thought much about the motives of occupational offenders. To me, they committed these crimes because they were crooks. But the company—certainly progressive on the antifraud front at the time—wanted me to invest the resources to find out why and how employees go bad, so they could possibly do something to prevent it. This quest took me to the vast libraries of The University of Texas at Austin, which led me to Cressey’s early research. After reading his book, I realized that Cressey had described the embezzlers I had encountered to a “T.” I wanted to meet him.

Finding Cressey was easy enough. I made two phone calls and found that he was still alive, well, and teaching in Santa Barbara. He was in the telephone book, and I called him. Immediately, he agreed to meet me the next time I came to California. That began what became a very close relationship between us that lasted until his untimely death in 1987. It was he who recognized the real value of combining the theorist with the practitioner. Cressey used to proclaim that he learned as much from me as I from him. But then, in addition to his brilliance, he was one of the most gracious people I have ever met. Although we were only together professionally for four years, we covered a lot of ground. Cressey was convinced there was a need for an organization devoted exclusively to fraud detection and deterrence. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners, started about a year after his death, is in existence in large measure because of Cressey’s vision. Moreover, although Cressey didn’t know it at the time, he created the concept of what eventually became the certified fraud examiner. Cressey theorized that it was time for a new type of corporate cop—one trained in detecting and deterring the crime of fraud. Cressey pointed out that the traditional policeman was ill equipped to deal with sophisticated financial crimes, as were traditional accountants. A hybrid professional was needed; someone trained not only in accounting, but also in investigation methods, someone as comfortable interviewing a suspect as reading a balance sheet. Thus, the certified fraud examiner was born.

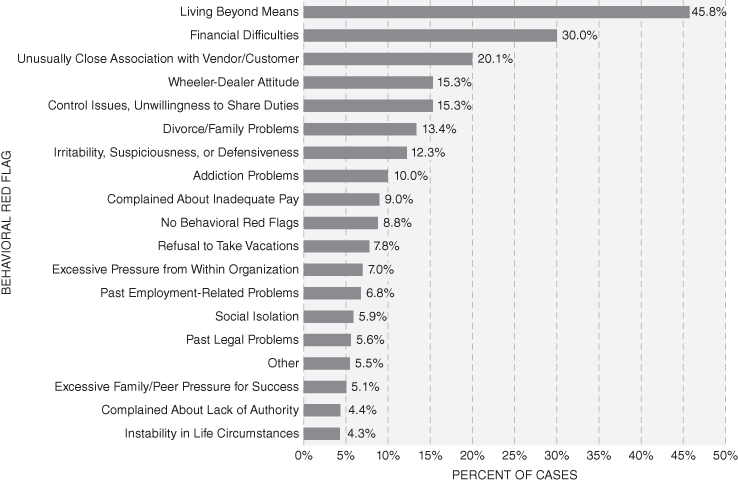

In Figure 2-4 from the ACFE’s 2016 Report to the Nations, survey respondents provided their observations with regard to which, if any, warning signs had been displayed by the perpetrator before the fraud was detected. These warning signs are consistent with various attributes of the fraud triangle: pressure, opportunity, and rationalization. In more than 91% of cases, at least one behavioral red flag was observed prior to detection, and in 57% of cases two or more red flags were seen. As Figure 2-4 illustrates, the six most common behavioral red flags are as follows: (1) living beyond means; (2) financial difficulties; (3) unusually close association with a vendor or customer; (4) a “wheeler-dealer” attitude involving shrewd or unscrupulous behavior; (5) excessive control issues or unwillingness to share duties; and (6) recent divorce or family problems. Approximately 79% of the perpetrators in the ACFE study displayed at least one of these six red flags during their schemes. What is even more notable is how consistent the distribution of red flags has been over time. The six most common red flags shown in Figure 2-4 have also been the six most common red flags in every report since 2008, when the ACFE first began tracking this data.

FIGURE 2-4 Behavioral red flags displayed by perpetrators

Module 3: The Role of Personal Integrity, Capability, Gender, and the Influence of the Organization

According to the Intelligencer/Wheeling News Register, law enforcement officials believe Shelly Lough took in excess of $1 million from Bethany College in an effort to keep another woman, Rachelle Weese, quiet about an alleged affair.

According to William J. Ihlenfeld II, U.S. attorney for the Northern District of West Virginia, the charge alleges Weese used violence or fear to extort money from Lough, who is the former manager of the cashier’s office at Bethany College. Over a 16-month period, Lough stole the money while she cashed payroll and personal checks from staff and students and altered records to hide the thefts.

The criminal complaint against Weese alleges that she threatened to reveal to Lough’s husband that Lough was in a relationship outside her marriage if she did not pay money. Although the exact amount Weese was paid in the alleged extortion attempt is not known, Ihlenfeld said the FBI has accounted for various sums adding up to a “substantial” amount. So far, the agency has identified from business records and other means some of Weese’s assets, including paying $35,000 cash for a new SUV and some “very expensive” jewelry totaling more than $25,000. A search warrant executed at Weese’s home also turned up $262,000 in cash.

Lough received probation and an order of restitution, while Jason Kirkland Weese, 31 at the time, who along with his wife Rachelle extorted more than $1 million will serve 63 months in prison for his role in the crime. Rachelle Weese’s sentence is not available.49

The challenge to the fraud triangle is that while it explains many garden variety frauds, oftentimes, the fraudster’s decision-making process, the facts and circumstances surrounding the bad act are complex. In this module, we offer research findings that supplement the early works of Sutherland and Cressey.

The Fraud Scale

Another pioneer researcher in occupational fraud and abuse—and another person instrumental in the creation of the certified fraud examiner program—was Dr. Steve Albrecht. Unlike Cressey, Albrecht was educated as an accountant. Albrecht agreed with Cressey’s vision—traditional accountants, he said, were poorly equipped to deal with complex financial crimes.

Albrecht’s research contributions in fraud have been enormous. In the early 1980s, he and two of his colleagues, Keith Howe and Marshall Romney, conducted an analysis of 212 frauds, leading to their book entitled Deterring Fraud: The Internal Auditor’s Perspective.50 The participants in the survey were internal auditors of companies that had been victims of fraud.

Albrecht and his colleagues believed that, taken as a group, occupational fraud perpetrators are hard to profile and that fraud is difficult to predict. His research included an effort to assemble a complete list of pressure, opportunity, and integrity variables, resulting in a list of fifty possible red flags or indicators of occupational fraud and abuse. These variables fell into two principal categories: perpetrator characteristics and organizational environment. Table 2-1 shows the complete list of occupational fraud red flags that Albrecht identified.51

TABLE 2-1 Occupational Fraud Red Flags

| Personal characteristics | Organizational environment |

|

|

The researchers gave participants both sets of twenty-five motivating factors and asked which factors were present in the frauds they had dealt with. Participants were asked to rank these factors on a seven-point scale indicating the degree to which each factor existed in their specific frauds. The ten most highly ranked factors from the list of personal characteristics, based on this study, are as follows52:

- Living beyond their means

- An overwhelming desire for personal gain

- High personal debts

- A close association with customers

- Feeling pay was not commensurate with responsibility

- A wheeler-dealer attitude

- Strong challenge to beat the system

- Excessive gambling habits

- Undue family or peer pressure

- No recognition for job performance

As you can see from the list, these motivators are very similar to the nonshareable financial problems and rationalizations Cressey identified.

The ten most highly ranked factors from the list dealing with organizational environment are as follows53:

- Placing too much trust in key employees

- Lack of proper procedures for authorization of transactions

- Inadequate disclosures of personal investments and incomes

- No separation of authorization of transactions from the custody of related assets

- Lack of independent checks on performance

- Inadequate attention to details

- No separation of custody of assets from the accounting for those assets

- No separation of duties between accounting function

- Lack of clear lines of authority and responsibility

- Department that is not frequently reviewed by internal auditors

Readers are likely to notice that Dr. Albrecht explicitly introduced the role of the organization into the actions of the fraudsters. This role was inherent in Cressey’s efforts but Albrecht brought these issues to the forefront.

Most of the factors on this list affect employees’ opportunity to commit fraud without being caught. Opportunity, as you will recall, was the second factor identified in Cressey’s fraud triangle. In many ways, the study by Albrecht et al. supported Cressey’s model. Like Cressey’s study, the Albrecht study suggests that there are three factors involved in occupational frauds:

… it appears that three elements must be present for a fraud to be committed: a situational pressure (nonshareable financial pressure), a perceived opportunity to commit and conceal the dishonest act (a way to secretly resolve the dishonest act or the lack of deterrence by management), and some way to rationalize (verbalize) the act as either being inconsistent with one’s personal level of integrity or justifiable.54

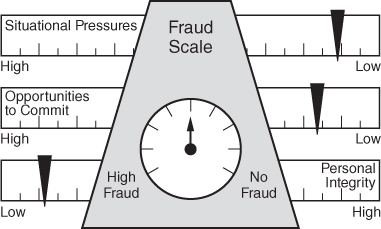

Armed with these research findings, Albrecht substituted personal integrity for rationalization and developed the “Fraud Scale” (Figure 2-5), which included the components of situational pressures, perceived opportunities, and personal integrity.55 When situational pressures and perceived opportunities are high and personal integrity is low, occupational fraud is much more likely to occur than when the opposite is true.56

FIGURE 2-5 The fraud scale

Albrecht described situational pressures as “the immediate problems individuals experience within their environments, the most overwhelming of which are probably high personal debts or financial losses.”57 Opportunities to commit fraud, Albrecht says, may be created by individuals or by deficient or missing internal controls. Personal integrity “refers to the personal code of ethical behavior each person adopts. While this factor appears to be a straightforward determination of whether the person is honest or dishonest, moral development research indicates that the issue is more complex.”58

In addition to its findings on motivating factors of occupational fraud, the Albrecht study also disclosed several interesting relationships between the perpetrators and the frauds they committed. For example, perpetrators of large frauds used the proceeds to purchase new homes and expensive automobiles, recreation property, and expensive vacations; support extramarital relationships; and make speculative investments. Those committing small frauds did not.59

There were other observations: perpetrators who were interested primarily in “beating the system” committed larger frauds. However, perpetrators who believed their pay was not adequate committed primarily small frauds. Lack of segregation of responsibilities, placing undeserved trust in key employees, imposing unrealistic goals, and operating on a crisis basis were all pressures or weaknesses associated with large frauds. College graduates were less likely to spend the proceeds of their loot to take extravagant vacations, purchase recreational property, support extramarital relationships, and buy expensive automobiles. Finally, those with lower salaries were more likely to have a prior criminal record.60

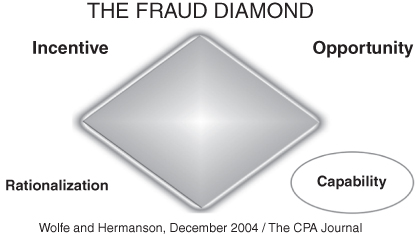

Capability and Arrogance

In a 2004 CPA Journal article, Wolfe and Hermanson61 argue that the fraud triangle could be enhanced to improve both fraud prevention and detection by considering a fourth element, capability. The authors altered the fraud triangle by presenting a four-sided fraud diamond (Figure 2-6). The fourth side adds an individual’s capability, which is tied to an individual’s personal traits and abilities. The authors suggest that capability plays an important role in whether fraud may actually occur.

FIGURE 2-6 The fraud diamond

Source: Wolfe and Hermanson, December 2004/The CPA Journal.

Examining evidence associated with multibillion-dollar fraud, Wolfe and Hermanson suggest that many of these large-dollar frauds would not have occurred without the perpetrator(s) having the right capabilities. As described by the authors, opportunity opens the door to fraud, incentive and rationalization draw the fraudster closer to the door, but the fraudster must have the capability to recognize the opportunity to walk through that door to commit the fraudulent act and conceal it.

Essential traits thought necessary for committing fraud, especially for large sums over long periods of time, include a combination of intelligence, position, ego, and the ability to deal well with stress. The person’s position or function within the organization may furnish the ability to create or exploit an opportunity for fraud. Additionally, the potential perpetrator must have sufficient knowledge to understand and exploit internal control weaknesses and to use position, function, or authorized access to his or her advantage. The largest frauds are committed by intelligent, experienced, and creative people with a solid grasp of company controls and vulnerabilities. This knowledge is used to leverage the person’s responsibility over, or authorized access to, personnel, systems, or assets. This type of person has a strong ego and great confidence that he will not be detected, or he believes that he could easily talk himself out of trouble, if caught.

Further, as noted by Pavlo and Weinburg, committing and managing a fraud over a long period of time can be extremely stressful.62 Therefore, in addition to being knowledgeable and confident, a successful fraudster also deals well with the stress of committing and concealing the fraud.

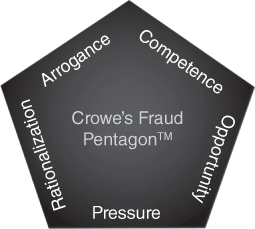

In 2010, Jonathan Marks argued for examination of the role of arrogance in fraud. Arrogance, or lack of conscience, is an attitude of superiority and entitlement or greed on the part of a person who believes that corporate policies and procedures simply do not apply to him. This person, perhaps fueled by today’s compensation structures, has disregard for the consequences bestowed upon his victims. Competence and arrogance play a major role in determining whether an employee today has what it takes to perpetrate a fraud (Figure 2-7).

FIGURE 2-7 Crowe’s Fraud Pentagon™

The Role of the Organization

Ramamoorti, Morrison, Koletar, and Pope in their 2013 book, A.B.C.’s of Behavioral Forensics: Applying Psychology to Financial fraud Prevention and Detection, offer three levels of the fraud paradigm: bad apples (i.e., individuals such as employees) can collude into bad bushels (i.e., groups of employees), which may cause the whole crop (i.e., organization) to be ruined.63 While providing insight into fraud acts, these authors are not the first to suggest that the organization plays a role in fraud.

In 1983, Richard C. Hollinger and John P. Clark published federally funded research involving surveys of nearly 10,000 American workers. In their book, Theft by Employees, the two researchers reached a different conclusion from Cressey. They found that employees steal primarily as a result of workplace conditions. They also concluded that the true costs of employee theft are vastly understated: “In sum, when we take into consideration the incalculable social costs … the grand total paid for theft in the workplace is no doubt grossly underestimated by the available financial estimates.”64 Following is a summary of the Hollinger and Clark research with respect to production deviance.65

Employee Deviance

Employee theft is at one extreme of employee deviance, which can be defined as conduct detrimental to the organization and to the employee. At the other extreme is counterproductive employee behavior, such as goldbricking and abuse of sick leave. Hollinger and Clark defined two basic categories of employee deviant behavior: (1) acts by employees against property and (2) violations of the norms regulating acceptable levels of production. The former includes misuse and theft of company property, such as cash or inventory. The latter involves acts of employee deviance that affect productivity. See Table 2-2 for a summary.

TABLE 2-2 Combined Phase I and Phase II Production-Deviance Items and Percentage of Reported Involvement, by Sector

Adapted from Richard C. Hollinger and John P. Clark, Theft by Employees. Lexington: Lexington Books, 1983, p. 45.

| Involvement | |||||

| Items | Almost daily | About once a week | Four to twelve times a year | One to three times a year | Total |

| Retail Sector (N = 3, 567) | |||||

| Take a long lunch or break without approval | 6.9 | 13.3 | 15.5 | 20.3 | 56 |

| Come to work late or leave early | 0.9 | 3.4 | 10.8 | 17.2 | 32.3 |

| Use sick leave when not sick | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3.5 | 13.4 | 17.1 |

| Do slow or sloppy work | 0.3 | 1.5 | 4.1 | 9.8 | 15.7 |

| Work under the influence of alcohol or drugs | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.6 | 4.6 | 7.5 |

| Total involved in production deviance | 65.4 | ||||

| Hospital Sector (N = 4, 111) | |||||

| Take a long lunch or break without approval | 8.5 | 13.5 | 17.4 | 17.8 | 57.2 |

| Come to work late or leave early | 1 | 3.5 | 9.6 | 14.9 | 29 |

| Use sick leave when not sick | 0 | 0.2 | 5.7 | 26.9 | 32.8 |

| Do slow or sloppy work | 0.2 | 0.8 | 4.1 | 5.9 | 11 |

| Work under the influence of alcohol or drugs | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 3.2 |

| Total involved in production deviance | 69.2 | ||||

| Manufacturing Sector (N = 1, 497) | |||||

| Take a long lunch or break without approval | 18 | 23.5 | 22 | 8.5 | 72 |

| Come to work late or leave early | 1.9 | 9 | 19.4 | 13.8 | 44.1 |

| Use sick leave when not sick | 0 | 0.2 | 9.6 | 28.6 | 38.4 |

| Do slow or sloppy work | 0.5 | 1.3 | 5.7 | 5 | 12.5 |

| Work under the influence of alcohol or drugs | 1.1 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 7.3 | 12.8 |

| Total involved in production deviance | 82.2 | ||||

Job Satisfaction and Deviance