Chapter 1

JESUS

The Catholic Church has always claimed Jesus of Nazareth as its founder, and nearly everyone is familiar with the basic facts about this dynamic Jewish preacher and healer who was born around the turn of the first century A.D. (probably between 6 B.C. and A.D. 6) and was crucified by the Romans between A.D. 28 and 30. His early years were spent at Nazareth in Galilee with parents who were of lowly origin. At some point in his early manhood he felt a call to preach the coming of God’s kingdom and began to gather huge crowds from the villages and towns in the region northwest of the Lake of Galilee; they were spellbound by his marvelous sermons and extraordinary healings. Well versed in the written and oral traditions of his Jewish religion, he presupposed in his preaching the basic Jewish faith in one God, the Lord of history, God’s special covenant with the Jews, and the sacredness of the moral precepts of the Torah or Law, which his people regarded as the revealed will of God. The climax of his ministry came when he entered Jerusalem in triumph, only to be apprehended and crucified by the Romans as a political agitator.

His early life is wrapped in almost complete obscurity. Our only important sources for his life—the Gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John— tell us very little about this period; Mark and John pass over it altogether; Matthew and Luke each devote their first two chapters to an account of his infancy, but we can’t be sure how much of this is history. It is, in fact, difficult to fit these first chapters of Matthew and Luke into any definite literary category; many scholars regard them as a type of Jewish Midrash—a commentary on Scripture that often used imaginative invention of episodes in order to illustrate biblical themes.

One indication of their nonhistorical character is the important differences—if not outright contradictions—between Matthew and Luke’s accounts. Matthew, for instance, dates the birth of Jesus during Herod’s reign—that is, not later than 4 B.C. (the date of Herod’s death), while Luke dates it during the period when Quirinius was legate of Syria, which according to the historian Josephus was from A.D. 6 to 9. Moreover, the two evangelists disagree in the names they list in the genealogy they attribute to Jesus. The theological insight they intend to convey, however, is clear: Jesus, the son of David and Son of God, was the long-awaited Messiah who came to bring salvation to all—both Jews and Gentiles.

When we come to the so-called public life of Jesus, which begins with his baptism by John at the River Jordan, we must admit that we do not have the kind of biographical details that readers look for today, such as descriptions of his physical appearance and personal habits, some idea of his psychological development, or the influences that shaped his personality.

But there is no need for skepticism. More than a century of rigorous critical analysis of the New Testament has in no way disproven the constant belief of Christians that their Scriptures are based on the actual words and deeds of a unique historical personage.

The Gospels, as we’ve said, constitute—practically speaking—our only source of historical facts about Jesus, and they were written from forty to seventy years after his death. Their authors drew on an oral tradition that disseminated stories about the deeds and words of Jesus in the form of sermons and catechetical and liturgical material. Mark, we believe, was the first to cast this oral tradition in the form of a Gospel—a unique literary genre which he invented. His Gospel appeared shortly before the fall of Jerusalem, which occurred in the year 70. Some ten years later, Matthew and Luke each produced a Gospel by using Mark’s work plus a collection of the words of Jesus (often referred to by scholars as Q, for Quelle, German for “source”) and also some special material that each evangelist had at hand. Finally, at the turn of the century, the author known as John produced the fourth Gospel, which differs considerably from the other three in its portrait of Jesus.

The Gospels were not meant to be a historical or biographical account of Jesus. They were written to convert unbelievers to faith in Jesus as the Messiah of God, risen and living now in his church and coming again to judge all men. Their authors did not deliberately invent or falsify facts about Jesus, but they were not primarily concerned with historical accuracy. They readily included material drawn from the Christian communities’ experience of the risen Jesus. Words, for instance, were put in the mouth of Jesus and stories were told about him which, though not historical in the strict sense, nevertheless, in the minds of the evangelists, fittingly expressed the real meaning and intent of Jesus as faith had come to perceive him. For this reason, scholars have come to make a distinction between the Jesus of history and the Christ of faith.

To find the Jesus of history, we have to sift through the material presented in the Gospels and try to determine by internal evidence what Jesus actually did and said as distinguished from what represents later interpretation. As a general rule, scholars hold that whatever cannot be deduced or explained from the Judaism of Jesus’ time or from primitive Christianity should be ascribed to the Jesus of history. What this means specifically is that while historical criticism makes it impossible to reconstruct a biography of Jesus in the ordinary sense, it does permit us to recover a considerable amount of authentic Jesus material. In fact, by adhering to the historical critical method we can determine “the typical basic features and outlines of Jesus’ proclamation, behavior, and fate.”1

All attempts to trace the origin of Jesus’ call to his divine mission are hindered by the fragmentary nature of the records. But there is good reason to suppose that his baptism by John was decisive in this regard. At least all our accounts agree that at his baptism “the Spirit descended on him”—a biblical phrase denoting the call of someone to be God’s messenger.

The message that Jesus proclaimed was simple in formula yet inexhaustible: “The kingdom of God is at hand, repent!” Matthew puts the same words on the lips of John, but there is no doubt that he regarded John as only the herald of Jesus, through whose ministry God actually broke into human history in an absolutely unprecedented and definitive way.

Some scholars argue that Jesus announced this incursion of God into history as a purely future thing involving a cosmic catastrophe and the end of the world. However, there is now growing agreement that there is both a present and a future reference in Jesus’ teaching: The reign of God already at work in his ministry was moving toward a consummation in the future.2 Some of his parables—like the one about the prodigal son who was welcomed back with love by the father whose bounty he had wasted—emphasize the point that God with fantastic goodness and generosity was already extending mercy to sinners. And when Jesus ate and drank with publicans and harlots, the meaning he intended was clear: Salvation is offered now to all, a gift in no way dependent on one’s prior righteousness.

It is thus clear, as the Jewish scholar David Flusser says, that Jesus is the “only Jew known to us from ancient times” who proclaimed that the “new age of salvation had already begun.”3 On the other hand, there is a strong tension in Jesus’ proclamation between the present salvific action of God and its fulfillment in the future. God would intervene to establish something radically new; it would be a cataclysm bringing an end to all earthly hopes and schemes. So Jesus spoke in terms of extreme urgency about the need to repent and to be ready for the inbreaking of God into history.

Jesus not only preached the good news of the kingdom, he also gathered his followers into a fellowship. They often took their meals together, celebrating joyfully their new covenant with God while they anticipated the glorious banquet to come in the kingdom of heaven. He called them the light of the world, the city of God, the salt of the earth. They were a family whose common devotion to God’s will united them far more intensely than any bonds of flesh and blood.

In some ways all of this resembled other spiritual movements of his day. Another Jewish group—the Essenes, for instance—had, as the Dead Sea Scrolls show, the same sense of joy at the imminent advent of God’s kingdom. They too practiced renunciation of personal possessions and their leader too advocated celibacy. And from them Jesus may have derived his doctrine of not resisting evildoers. But they held to a sharp separation from the common herd, and many of them secluded themselves in monasteries near the Dead Sea. Jesus, on the other hand, opposed any form of exclusivism; it would have been at odds with his main doctrine of the boundless nature of God’s offer of grace. So he deliberately sought out the social outcasts and even showed them special signs of his favor.

The members of Jesus’ kingdom felt a most intimate relationship with God, whom they loved to call Father. And he taught them to live sincerely as God’s children. Though a tiny group, poor and despised, they had the greatest of conceivable treasures—the absolute assurance of salvation, a salvation not dependent on their own achievements but on the unlimited goodness of God. Nor must they worry about daily necessities; their heavenly Father’s providence, which reached even to the tiniest sparrow, would surely not desert them. Not that they would be spared any of the manifold forms of suffering and anguish that life brings to everyone. But there was no need for them to comprehend the unfathomable mystery of evil; enough to know that suffering when accepted brings one closer to God, while death itself is only the prelude to union with him.

Life in God’s kingdom inaugurated by Jesus found its purest expression in prayer, and Jesus stood before his followers as a constant example of prayer-fulness. As a pious Jew he observed the three liturgical hours of prayer daily and took part in the worship of synagogue and Temple. But, as in other matters touching the formal religion of the day, he challenged tradition and custom. He warned his followers against the spirit of routine and formalism so often characteristic of public prayer; he urged them to pray in secret as well, and he himself spent whole nights in prayer. Moreover, he gave them a distinctive prayer of their own, the Lord’s Prayer, whose brief petitions to the Father so perfectly express his own yearning for the ultimate fulfillment of the divine purpose in history.

Jesus did not make a radical break with the morality of the Torah. He still recognized the sacred law as the authentic voice of God, but he did not hesitate to modify it, as in his prohibition of divorce. The main thing he insisted on, however, was complete submission to the will of God in all things. It was all summed up in his command to love: God first and then all human beings without exception, foreigners as well as one’s own. This double commandment of love already existed in ancient Judaism, but Jesus radicalized it by removing all restrictions: One must love even one’s enemies. Moreover, Jesus emphasized the motive for loving: We were to love others out of gratitude for God’s love of us.

His encounter with the harlot in the house of Simon the Pharisee gave Jesus an occasion to drive home this point. The woman came in with an alabaster jar of ointment while Jesus was reclining, and she began to bathe his feet with her tears and wipe them with her hair, kissing them and anointing them with her ointment. When Simon reacted strongly at the sight of Jesus accepting such ministrations from a woman of the street, Jesus remonstrated with him. Whereas the woman had lavished signs of her love upon him, he said to Simon, “. . . you poured no water over my feet . . . You gave me no kiss . . . You did not anoint my head with oil . . .” And Jesus concluded that the woman was so loving because she was conscious of how much she herself needed forgiveness; “It is the man who is forgiven little who shows little love.” And he said to her, “Your sins are forgiven.”4

Accepting the rule of God meant radically changing one’s order of values. There must be no divided loyalty: Every form of attachment, whether to family, property, business, or whatever, must be relegated to second place in the heart of one who aspires to follow Jesus. And like the prophets, he warned them of the special danger of riches; money could so easily take the place of God in a man’s soul—for “no man can serve two masters.” Service of the kingdom might even mean the complete renunciation of all material goods; when Jesus sent out messengers to spread the good news he wanted them to go as poor men, and he recommended celibacy for the sake of the kingdom. In any case, every follower of Jesus must deny himself, for the kingdom could not be brought in without suffering.

Suffering and affliction, in fact, were to be seen in a totally new way. Not that they were desirable in themselves; but if one accepted the kingdom, then poverty, hunger, and bereavement were no longer the absolute evils they appeared to be, for they could not prevent one from enjoying the love of God and might even be of help in this regard, whereas the things men cherish most—riches, abundance of friends, comfort, and good times—were real evils if they hindered one from seeking the kingdom.

The originality of Jesus was found not so much in the novelty of his ideas (for most of them were already present in the traditions of his people) but in the way he brought them together, developed and harmonized them, and above all made them real in his own life with such unparalleled intensity.

Miracles and exorcisms play very prominent parts in the ministry of Jesus; to pass over them as a concession to “modern ideas” would be a serious omission. However, it is not easy to determine what actually happened, since an analysis of the tradition often shows that the brute historical fact was much reworked in the course of transmission. Moreover, parallels to the Gospel miracles have been found by scholars in contemporary pagan and rabbinic literature as well as in the Old Testament: storms quelled, water changed into wine, demons expelled, and so on.5 Nevertheless, the kernel of historical fact that they contain would seem to be that Jesus did exercise extraordinary powers of healing. And in an age when demons were held responsible for every form of evil afflicting man, he would inevitably be portrayed as a chaser of demons, as one victorious over all the forces that degrade man.

Christ Institutes the Eucharist. Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665). Louvre, Paris. © Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, New York.

The question of Jesus’ authority soon became a prime issue, for instead of appealing to traditional forms of authority, he invoked his own religious experience and urged his hearers to do the same. In the name of the primacy of love over law, he even attacked sacred Jewish traditions like the rigorous Sabbath observance and spoke slightingly of the Temple. His whole performance, in fact, constituted a tremendous challenge to the establishment, which it could hardly have left unanswered.

With a premonition of his approaching end, Jesus gathered his faithful for one last meal together—probably the night before the Jewish Passover— and offered them bread and wine, his body and blood, which would be sacrificed to establish the new covenant between God and humanity. Clearly his actions—the taking of bread and wine, the giving of thanks, the breaking of the bread, and the sharing of food and drink—were all well known and quite regular Jewish observances. But Jesus gave them an entirely new significance when he commanded them to be repeated as a memorial of his passion and as a pledge of his continuing presence with them and of his coming again.

According to the Gospels, that same night Jesus was arrested at the instigation of both Roman and Jewish officials, brought before a Jewish high court, the Sanhedrin, for a kind of grand-jury proceeding, and found guilty. The Gospels would have us believe that both political and religious motives were involved. In the eyes of the Jewish authorities, he appeared to be a messianic pretender who, like other would-be messiahs at the time, thought of the coming of God’s kingdom as necessitating a political revolution. Hence the Jewish leaders feared he might provoke a brutal repression by the Romans and bring ruin on the whole Jewish nation. The Sanhedrin also had purely religious reasons for wanting the death of Jesus: His claim to unique authority they regarded as blasphemy, and his words against the Temple and his criticism of the Jewish Law they considered sacrilege.

Then according to the Gospels, Pilate upon investigation found the political charge untenable, being perhaps most impressed by the unwillingness of Jesus’ followers to use force to defend him at the time of his capture. And so after interrogating him, he resolved to release him. But the Jewish leaders would not stand for this, and by threatening to report Pilate to Caesar, they forced him to have Jesus executed.

The question then occurs: Are the Gospel accounts of the arrest, trial, and execution of Jesus true to history? Many scholars today say no. They view the Gospel version of the tragedy as tendentious—reflecting the point of view that prevailed in the Church when they were written thirty to sixty years after the event. According to their theory, the authors of the Gospels aggravated the responsibility of the Jews for the death of Jesus and minimized Roman participation. Their intent would have been to allay any suspicions of the Romans that the Christian Church might be politically subversive by clearing the name of their founder of any such implication. So they falsely pictured Pilate as not taking the political charges against Jesus seriously and transferred the chief responsibility for Jesus’ death to the Jews.

Some scholars even go so far as to completely exonerate the Jewish authorities and reduce the whole affair to a political conflict between Jesus and the Romans. But while granting some measure of truth to this hypothesis, other scholars would not completely exonerate all the Jewish leaders. We have to suppose, they maintain, that a strong antipathy did exist between Jesus and some of the leaders—notably the temple priests—since it is a fact too deeply embedded in the tradition to be easily dismissed; and these leaders would surely have played some role in his death. In their eyes he might well have been viewed as a messianic pretender. While not constituting the whole Sanhedrin, his enemies would still have been a powerful group and would have interrogated him about his messianic pretensions and then handed him over to Pilate. For his part, Pilate would have had no qualms about quickly dispatching anyone who was in any way suspect of political subversion, even though he might not have been impressed by the seriousness of the accusation.

In any case, it all should have ended on Calvary. But something strange occurred, an experience that convinced Jesus’ followers that he was still alive and that radically changed their outlook.

What actually happened on that first Easter morning? We have a number of sources that attempt to describe the resurrection of Jesus: the Gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, and the epistles of St. Paul. But when we analyze them we find a considerable variety in the way they relate the event. Thus they do not agree as to where and to whom Jesus first appeared (in Matthew and John, for example, Jesus appears first to Mary Magdalene and her companions in Jerusalem, while according to Paul he appeared first to Peter; John and Luke place his first appearance to his disciples in Jerusalem, Matthew in Galilee). So it is very difficult to form a consistent historical sequence of events. This is in decided contrast with the Passion accounts, which fit all the details into a consistent intelligible sequence.

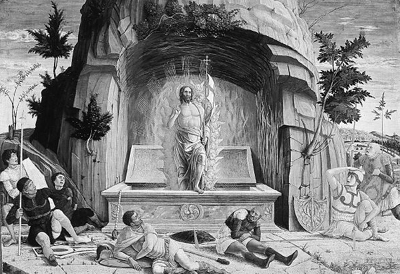

Resurrection of Christ. Andrea Mantegna (1431–1506). Musée des Beaux-Arts, Tours, France. © Scala/Art Resource, New York.

Basic, however, to all the accounts was an appearance of Jesus to his followers that inaugurated the Christian community but that each individual community related in a way that reflected its own mentality, local associations, and theological conceptions.

The methods of historical criticism now make it possible to go behind the divergencies and reconstruct the probable sequence of events. Joachim Jeremias offers the following:

Mary Magdalene went alone at dawn on Easter Day to the tomb to mourn there for Jesus. From a distance she could see that the stone sealing the tomb had been rolled back. Concluding immediately that someone had broken in to steal the body, she ran to give the alarm to Peter. He in turn raced to the tomb and found the linen burial cloths lying about and the tomb indeed empty. He rushed back to the disciples. Then the decisive event occurred: The risen Lord appeared to Peter.