Chapter 6

THE FINAL VICTORY OVER PAGANISM

At the dawn of the fourth century, Christianity was still the religion of only a minority of Roman citizens, but by the end of the century it was embraced by the majority, and Emperor Theodosius proclaimed it the official religion of the Empire in the year 380. The story of its irresistible progress constitutes one of the most dramatic chapters in the history of the early Church.

One development that pointed to its eventual triumph over paganism was the mass influx of peasants into the fold during the latter part of the third century. Until the third century, Christianity was almost exclusively urban in character and rooted in the middle and lower urban classes. The countryside had remained stubbornly pagan, conservatively attached to their local deities and superstitions and their old ways of life. There was also a language barrier, for the peasants clung to their ancient Coptic, Berber, Syriac, Thracian, or Celtic tongues. It was quite normal, therefore, for missionaries to bypass the rural areas and simply move from city to city.

It was only in the second half of the third century that Christianity began to make considerable inroads into the rural lands. In many of the great provinces of the Empire, the peasants deserted the temples of their ancestral gods and turned to Christ. In one North African township, dedication tablets tell the tale: The last one dedicated to Saturn-Baal Hammon is dated 272; all subsequent ones uncovered have proven to be Christian. By the year 300, North Africa was largely Christian. In Asia Minor the story was similar. The most famous of the missionaries there was Gregory the Wonderworker. His well-known remark that he found only seventeen Christians when he arrived in Neo-Cesarea in 243 and left only seventeen pagans when he was ready to die thirty years later is probably close to the truth, since it is in accord with the general history of the province. Numerous tombstones found in the countryside, dating between 248 and 279, are patently Christian in their wording and often pay homage to the deceased as “a soldier of Christ.” In Egypt and probably also in Syria, there was the same widespread turning to Christ by the peasants. Eusebius gives us an eyewitness account of the conversion of the Copts to Christianity when he was in Egypt in 311–12. Altars to Christ abounded, he reports, and the majority of the population were already Christian.

A big change in the complexion of the aristocracy also contributed greatly to the progress of Christianity. Like the peasants, but for different reasons, the aristocrats had remained pagan for the most part. Prejudices instilled in them by their education and their class made them hard to reach. Trained in a curriculum almost exclusively devoted to rhetoric, they learned to put a great premium on mere verbal elegance and so were snobbishly inclined to dismiss the holy books of the Christians as uncouth and barbarian. Moreover, as scions— supposedly—of the Gracchi and Scipios of the ancient Roman nobility, they were moved by a sense of pious family obligation in trying to maintain their religious traditions.

But this situation began to change in the fourth century. Circumstances fostered an upward social mobility, and numerous members of the middle classes were able to move into the equestrian or senatorial order; and many of these were already Christian or disposed to become Christian. This restructuring of the social order began with Diocletian’s reorganization, which enabled many members of the lower classes to take high administrative offices. This smoothed the way for Constantine’s pro-Christian policies, since it meant he was not hampered by an entrenched aristocracy in key offices who were hostile to religious innovation. He and his successors furthered this social mobility by greatly enlarging the senatorial order, particularly in the new Senate at Constantinople, where Constantine enrolled thousands of new members. Many of these came from the middle classes. Many were barristers of humble origins. Many of them were already Christian, while many of the others had no problem in converting to the new faith now favored by the imperial court. All of this had a profound impact on the religious situation; it meant that Constantine and his Christian successors were able to build up an aristocracy sympathetic to their religious policies.

In consequence, paganism in the East put up no serious political resistance to the pro-Christian policies of the fourth-century Emperors. The same was not true, however, of the West, where the senatorial order remained quite pagan, and as late as 380 stoutly resisted, though in vain, the Emperor’s command to remove the pagan statue of Victory from their chamber.

This pro-Christian imperial policy, as we have seen, began with Constantine, who favored the Christians and only tolerated paganism, hoping to see it die a natural death. His three sons, however, who succeeded him at his death in 337, took a more resolute stance. This was especially true of Constantius, who was left sole ruler in 350. He aimed at the total extirpation of paganism; he ordered the temples closed and imposed the death penalty for participating in sacrifices. Some pagans still managed to carry on their worship at the great shrines in Heliopolis, Rome, and Alexandria, but they were caught in a tight squeeze.

This growing dominance of the Christians was severely challenged, however, when the new Emperor, Julian, took office in 360. Upon assuming the imperial purple he marched into Constantinople, declared himself a pagan, and stated his intention of restoring the ancient religion. As a boy raised in the imperial household he was baptized Christian and forced to conform to his uncle’s religion; but the bookish and dreamy lad secretly dedicated himself to the ancient gods, and once securely in power he tore off his mask and showed his true colors. No doubt his negative view of Christianity was influenced by his dolorous experiences in the professedly Christian imperial household, where the death of his Uncle Constantine was attended by a bloodbath, with the massacre of cousins and relatives and where his own life hung in the balance for a long time.

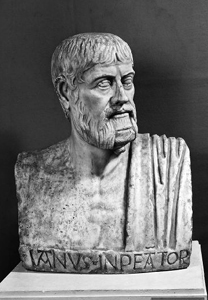

Bust of the Roman Emperor Julian the Apostate (361–70 C.E.). Musei Capitolini, Rome. © Giraudon/Art Resource, New York.

But his “apostasy” went much deeper than that. For Julian the religion of the gods was not merely a religion but also the very marrow of Romanitas— the highest level of cultural achievement possible to man and the source of Rome’s sublime morality. Christianity, on the other hand, was merely a recurrence of the age-old barbarism, a silly religion based on fables about an illiterate peasant whose teachings were weak, impractical, and socially subversive.

Accordingly, Julian moved quickly to reverse the religious policies of his predecessors: The privileges and immunities granted to the Christian priests were revoked; the labarum (a military banner decorated with the monogram of Christ) and other Christian emblems were abolished. A great effort was made to revitalize the pagan religion by conferring favors on its priests, importing Oriental cultic rites, and developing its theology along the lines of Neo-Platonism. Julian issued minute directions for sacrificial rites and ordered all the gods to be invoked—Saturn, Jupiter, Apollo, Mars, Pluto, Bacchus, and Venus, and even the Oriental deities, Mithras and Isis. He exhorted his devotees to live lives of austere morality and to outdo the Christians in works of charity.

But Julian’s anti-Christian reaction failed. His mechanical assemblage of outdated ideas and foreign importations could not be given the breath of life; it was no match for the simple but vital Christian message. It could not compete with a religion that freed man from rituals and statutory morality in order to serve and love his neighbor as himself in imitation of his divine master, Jesus Christ. After a brief reign Julian came to an inglorious end in 363 on the sands of Mesopotamia after being struck by a Persian arrow. His death marked the definitive triumph of Christianity in the Empire.

A clear indication of this was given when his own troops elected as his successor Jovian, a general conspicuous for his Christian faith; he immediately restored official status and privilege to the Christian Church. His reign was short (363–64), and the army then raised another Christian, Valentinian, to the throne, who ruled with his brother Valens. They spent most of their energies on the frontier trying to halt the barbarians, Valentinian facing the Franks and Saxons while fortifying the Rhine against the Alemanni, while Valens was on the Danube, against the Goths. It was Valens who brought the Empire to the brink of collapse by his defeat at Adrianople in 378, where the Goths slaughtered two thirds of the Roman army, including himself.

While the Empire continued on its downward path, the Church continued to gain in popular favor and official standing in spite of internal dissension. The Church gradually became the only true bastion of freedom within the totalitarian Roman state, where the collapse of the old civic institutions had deprived its citizens of their political rights and loaded them with heavy economic disabilities. In the Church, however, they still could have a sense of participation and of some control over their destiny. Here they found also not only spiritual liberty but material assistance as well.

One of the most potent reasons, in fact, for the appeal of the Church to the masses was its magnificent system of charity, which aroused the admiration even of Julian the Apostate. Eventually it broadened out to include a whole organism of institutions, including orphanages, hospitals, inns for travelers, foundling homes, and old-age homes—so much so that as the state became increasingly unable to cope with the immense burden of social distress brought about by the barbarian invasions of the fourth and fifth centuries, it relied more and more on the Church.

The bishop was even given public judicial authority in all matters concerning care of the poor and social welfare. He was supposed to eat daily with the poor, and he often did. Ambrose wanted no gold vessels on the altars when there were captives to be ransomed, while at a later period Gregory the Great felt personal guilt when a poor man was found dead of starvation in his city. The bishop, moreover, stood forth as the champion of the oppressed against the clumsy and insensitive imperial bureaucracy and gradually became the most important figure in the city. While clothed in an aura of supernatural prestige, he enjoyed at the same time a popular authority, since he was elected by the people.

The immense influence of the Church over the masses was recognized by Emperors Gratian and Theodosius, who finally established it as the basis of the whole social order. This is the intent of the epoch-making decree promulgated by Theodosius from Thessalonica on February 27, 380, which began: “We desire that all peoples who fall beneath the sway of our imperial clemency should profess the faith which we believe has been communicated by the Apostle Peter to the Romans and maintained in its traditional form to the present day. . . .”29 Paganism was declared illegal, while privileges were granted to the Catholic clergy; they were accorded immunity from trial except in ecclesiastical courts. Roman law was revised in harmony with Christian principles: The Sunday observance laws of Constantine were revived and enlarged, with the banning of public or private secular activities. The pagan calendar was revised and given a Christian character; Christmas and Easter were made legal holidays. Various forms of heresy were proscribed and the property of their adherents confiscated. Pagan rites and practices were outlawed and the pagan priesthood abolished.

Marble head of Emperor Theodosius I, the Great (379–95 C.E.). Louvre, Paris. © Erich Lessing/Art Resource, New York.

Gratian ordered the removal of the statue and altar of Victory from the Senate house in Rome in 382; his successor, Valentinian II, influenced by Ambrose and Pope Damasus, turned a deaf ear to the embassy of pagan senators who demanded its restoration. The co-Emperor of the East, Theodosius, gave memorable witness to his personal respect for the authority of the Church when after ordering a horrible massacre of the citizens of Thessalonica (390) he accepted the rebuke of Bishop Ambrose and did public penance at the door of the cathedral in Milan. (This one act did more than tons of theology to illustrate the authority of the Church over the state and lay the foundations of the papal monarchy over medieval Christendom.)

What explains the triumph of the Church? Besides the factors already alluded to, we would point out, first, the simple force of the Church’s incomparable organization with all its ramifications, from the wall of Hadrian to the Euphrates River. It had no rival in this regard. Then we must remember that in a time of extreme social decay, it provided a refuge for the oppressed and acted as an agent of social justice. And finally, in the words of one of the great historians of this period, “In its high ethical appeal, its banishment of the blood and sacrifice from worship, and adherence to a god at once transcendent and active in the universe Christianity presented in a coherent form ideas to which the pagan world was groping.”30