Chapter 7

JEROME

The Western Church originally recognized four men as its doctors or teachers par excellence: Ambrose, Augustine, Jerome, and Gregory the Great. Each of them played a singular role in shaping the theology and spirituality of the Catholic Church. In this chapter we intend to focus on Jerome, whose long life spanned a good part of the fourth century and in many ways epitomizes the history of his times.

Jerome was born of wealthy Christian parents, probably in 331, in the town of Striden, in the Latin-speaking Roman province of Dalmatia, a part of modern Yugoslavia. While his early life is veiled in obscurity, we do know that he received an education that was superb for its time. He studied grammar at Rome under the celebrated Aelius Donatus, whose writings were used as textbooks throughout the Middle Ages. Under the great scholar’s tutelage for some four or five years Jerome made an intensive study of the Roman classics—Vergil, Cicero, Terence, Sallust, Horace, and others—nurturing in this way the literary talent that was to make him the greatest stylist of Christian antiquity. Further studies in rhetoric prolonged his stay at Rome for possibly another four or five years, a period during which he also began accumulating the books that were to make his library the most important private collection of the day.31 They were also years when he began to take his Christian faith more seriously; and in fact some time during this sojourn at Rome he sought the baptism which according to the custom of the day his parents had postponed. But his conversion to ascetical Christianity was still years away and there are indications that his ardent pursuit of learning was sometimes put aside for pursuits no less ardent but less ennobling, sexual adventures that were to cause him much remorse of conscience.

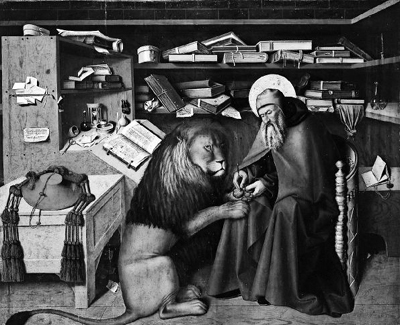

St. Jerome and the Lion. Colantonio (fl.1420–60). Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy. © Scala/Art Resource, New York.

Little is known about the next ten years or so of his life. It seems that at some point while traveling in Gaul he settled in Trier, a city often used as the western capital of the Empire during the fourth century. It was also one of the centers in the West of the new monastic movement that had just started to take hold there after firmly establishing itself in the East. While sojourning in Trier—possibly to find a career in government service—and influenced perhaps by this new movement, Jerome dedicated himself wholeheartedly to the Christian life and began a close study of the Bible and theology while practicing a high degree of prayer and detachment. He then returned to his native region to visit his family and friends, and he stopped at the city of Aquileia, which was also a center of the monastic movement. There he stayed with a priest friend, Chromatius, who had organized his household into a quasimonastic community. Jerome found this environment most congenial and was soon bubbling over with enthusiasm for the kind of ascetic life practiced by his friends. It was a happy period for Jerome but it was not to last. He was a man of explosive temperament with an uncontrollable, nasty tongue. A quarrel broke out and Jerome packed up his books and took off for the East, intending to visit Jerusalem. His long overland journey through Greece and Asia Minor was, however, arduous in the extreme and when he arrived at his friend Evagrius’ house in Antioch, he was broken in health and unable to continue on to Jerusalem.

It was at this point, it seems, while convalescing amid the comforts of Evagrius’ mansion, surrounded by his cherished books and intellectual companions, that Jerome made his momentous decision to fully embrace the ascetic life. In a dream he saw himself dragged before the Last Judgment seat and accused by the Judge of being a disciple of Cicero, not of Christ, and then flogged until his shoulders were black and blue. So affected was he by the vividness of the dream that he resolved to put aside the pagan classics for good and devote himself exclusively to the things of Christ.

Completely converted to the ascetic ideal, he took up his abode in the Syrian desert not far from Antioch. Many hermits already lived there seeking communion with God by practicing austerities of the most bizarre kind. They slept on the bare ground, loaded themselves with chains, ate only dates or raw herbs. Some, like the famous Simeon, even perched themselves permanently on the top of the pillars still standing amid the ruins of antiquity. In this sun-scorched barren retreat he spent several years praying, studying, barely keeping body and soul together while fending off the evil fantasies spawned by his sex-haunted imagination. “Although my only companions were scorpions and wild beasts, time and again I was mingling with the dances of girls.”32 To quell the flames of lust, he found a singular remedy: the study of Hebrew! With a convert from Judaism as his tutor, he began studying this difficult tongue. Jerome was the first Latin Christian to learn Hebrew and “indeed the first Christian of note at all apart from Origen (c. 185-c. 254).”33 His mastery of the tongue was far superior to Origen’s or any other Christian writer for centuries to come and it exerted a decisive influence on the shape of his future career.

While not much given to theological speculation, Jerome could not ignore the great controversy over the nature of the Godhead that was still agitating the Church. Theological differences with the monks in fact drove him from the desert back to Antioch, a city itself divided into a number of factions over the Arian issue. One of the factions was outright Arian, but even the orthodox were split between the followers of Paulinus who stuck to the formula mandated by the Council of Nicaea and the followers of Meletius who had adopted a theology which went beyond Nicaea in referring to the three members of the Trinity as the “three hypostases.” The conservative Jerome sided with Paulinus, who ordained him a priest.

The Emperor Valens’ death at Adrianople in 378 and the accession of the Nicene-minded co-emperors, Gratian in the West and Theodosius in the East, had great repercussions on the fortunes of the various parties. Under Theodosius’ leadership a church council was held at Constantinople in 381 (the Second Ecumenical Council) which saw the definitive triumph of Nicene orthodoxy. While marred by unseemly disorders, it officially reaffirmed the Nicene creed while also recognizing the “three hypostases” theology in terms acceptable to the West. At the same time the council endorsed the Meletian party at Antioch much to the dismay, no doubt, of Jerome who, though resident at Constantinople at the time of the council, makes no mention of it in his writings.

In the meantime, Jerome had embarked on a literary career by publishing a number of works that gained him considerable notice. One of these was his translation from the Greek, with many additions and supplements, of the Chronicle of Eusebius of Caesarea (d. 340). It was the most successful attempt at a history of the world up to that time and through Jerome’s endeavors it became one of the most popular books in the Middle Ages. Another project he undertook at this time—the translation of thirty-seven of Origen’s homilies—points to an intellectual interest that was to profoundly influence his intellectual and spiritual development. Jerome was fascinated with Origen’s writings for obvious reasons. As a biblical scholar, daring speculative theologian, and prolific polymath, Origen (d. c. 254) was the greatest mind produced by the Church before Constantine. Jerome’s enthusiasm for Origen at first knew no bounds and he often borrowed freely from the master’s writings. Later, when a strong anti-Origen movement surfaced in the Church, Jerome did a switch and played down his immense debt to the Alexandrian genius.

In 382 Jerome left Constantinople for Rome in the company of his bishop, Paulinus, and began one of the most important and most turbulent chapters in his life. It all started smoothly enough when the reigning Pope, Damasus (d. 384), took him into his service and made him a member of his intimate circle of advisers. This Pope, whose election in 382 was a rowdy affair marked by hand-to-hand fighting between rival factions, was himself a scholar of some distinction and a patron of learning. Damasus was much impressed by Jerome’s erudition and command of Hebrew and often consulted him on problems of scriptural interpretation. It was in fact at the Pope’s behest that Jerome began work on a project that was to constitute his most lasting achievement: a translation of the Bible from the original languages. Up to this point Christians had at their disposal a translation of the Bible called the Old Latin which in its Old Testament part was based not on the Hebrew original but on a Greek translation known as the Septuagint. This Old Latin version was in a great state of disorder with many variations that had crept into the text. The Pope did not want a completely new translation but only wanted Jerome to sort out the various readings and establish a standard version based on comparison with the original languages. It was a work that would take him more than twenty years to complete, and while in Rome he finished only the four gospels. Moreover, he soon abandoned the idea of simply revising the existing translation of the Old Testament. He decided to start fresh from the Hebrew original and produce an entirely new translation. This was a courageous undertaking, for his new rendering of many venerable readings of the Bible shocked the sensibilities of the faithful and he was roundly denounced throughout the Christian world. Even Augustine, as we shall see, found the new translation uncalled for. Jerome was pained but not surprised by the response and referred to his critics as “howling dogs who rage savagely against me.”34 But his translation slowly caught on and gradually achieved recognition as the standard, or “Vulgate,” Latin text of the Bible. Its influence on the religious imagination and literature of the West was immeasurable.

While in the employ of the Pope, Jerome struck up an acquaintance with a number of high-born Roman ladies of wealth who were practicing a rudimentary form of what would later be called convent life. Nuns as yet in the strict sense did not exist but these women were their forerunners; they lived in seclusion, vowed themselves to celibacy, and dedicated themselves to study and prayer. Firm now in the conviction that asceticism was the most perfect form of Christian life, and at the same time feeling deeply the need of female companionship, Jerome was delighted to make friends with these ladies who invited him to become their teacher and spiritual director. With two of them in particular, Paula and her daughter, Eustochium, he formed an extremely close and lasting friendship. To encourage them to persevere in their chosen way of life he composed some of his most eloquent treatises on the ascetic vocation. Jerome repeatedly exalts virginity in these treatises as the only appropriate state in life for the committed Christian; it was the original state willed by God before the Fall, while sexual intercourse and marriage should be regarded as an inferior choice, one of the unhappy consequences introduced by original sin. In one of his pamphlets, Against Jovinian, Jerome got so carried away and dwelt on the disagreeable aspects of marriage in such crude and excessive terms that even his friends were embarrassed and felt it necessary to remonstrate with him. Jerome’s response was characteristic:

In order to make my meaning quite clear, let me state that I should definitely like to see every man take a wife—the kind of man, that is, who perhaps is frightened of the dark and just cannot quite manage to lie down in his bed all alone.35

Many Roman Christians at the time were rather cool toward Jerome’s crusade for asceticism and virginity which they regarded as extremist. One of them was a layman, Helvidius, who in his published refutation of Jerome strove to prove that even Mary after the birth of Jesus lived a normal married life with Joseph. This attack on the perpetual virginity of the Mother of God aroused Jerome to an absolute fury which he unleashed in his reply, Against Helvidius. Though sprinkled with the gratuitous insults that came so readily to Jerome’s tongue, it was learned and persuasive enough to convince most of his contemporaries and demolish Helvidius. The perpetual virginity of Mary was henceforth to be an unassailable doctrine of Catholic Christianity. The pamphlet was also successful in converting many to Jerome’s view of consecrated celibacy as a superior state of life—a doctrine that would have tremendous influence on the development of Catholic spirituality and its sexual ethic.

As long as his patron Pope Damasus lived, Jerome could carry on his campaign for asceticism without too much hindrance. But with the death of the pontiff his situation radically changed. Many members of the Church at Rome were repelled by his extreme views; they regarded his type of asceticism as an Oriental intrusion. He also made many enemies by his frequent attacks on the conventional Christians who with the coming of Constantinian mass Christianity were now so numerous around him. Jerome found many targets for his satirical talent and indulged it to the full, showing no mercy as he lashed out at the worldly bishops living in luxury, the priests fawning on the rich, and the pseudo-virgins parading around in the company of young fops. With the elevation of Siricius (384–399) to the throne of the apostles, his enemies struck back. Some kind of formal charge was brought against him by the authorities, involving among other things his relations with Paula, it seems; and Jerome, while indignantly rejecting the accusation, found it necessary or expedient to leave the eternal city for good.

Paula and Eustochium followed him and after joining his company— probably at Antioch—they started out on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Helena, the mother of Constantine, at a great age made a pilgrimage to Palestine in 326 and with the help of her son carried out a program of restoring the places sacred to the memory of Jesus and ornamenting two of them, on the Mount of Olives and at Bethlehem, with imposing basilicas. Her action gave a great impetus to the practice of visiting the Holy Land and by Jerome’s time such pilgrimages were quite common. Jerome and his companions made an extensive tour of the holy places and the indefatigable scholar made a very detailed inventory of them, including a description of the Church of the Resurrection built by Constantine in Jerusalem over the cave associated with Jesus’ resurrection and the Church of the Nativity built by Helena over the cave which ancient tradition regarded as his birthplace.

The three pilgrims were enthralled by what they saw in the Holy Land and after a brief journey to visit the monks in the Egyptian desert decided to make their stay a permanent one. Fascinated above all by Bethlehem with its grotto of the Nativity, they decided to settle there in 386 and follow a monastic way of life. Jerome’s friends, Rufinus and Melania, had already established monasteries for Latin-speaking ascetics, separate ones for men and women, in Jerusalem on the Mount of Olives, and Jerome and Paula were eager to try out the same idea. Their two monasteries were eventually built and, thanks to the fame of their founders, soon attracted a number of recruits. As the basis for their rule of life they drew on their knowledge and experience of the Egyptian monks. Jerome freely adapted the type of monastic life inaugurated in Egypt by St. Pachomius, whose Rule he later translated. It prescribed an orderly routine of community life for the monks who, while living in individual cells, took their meals in common, engaged in manual labor to support themselves, and met for prayer at regular intervals throughout the day. Monasticism had by this time taken firm root in the East, but although publicized especially by the translation of St. Athanasius’ Life of St. Antony, it had not yet taken much hold in the West. The monastic communities of Jerome and Rufinus, which adapted Egyptian monasticism to the Latin temperament, were well advertised especially through the writings and letters of Jerome and much visited by pilgrims from the West and no doubt they contributed greatly to the spread of monasticism in the West during the fifth century.

The founding of the monasteries was a dream come true for Jerome, and in spite of all the problems and worries—financial ones especially—he continued to rule and guide his monks for thirty years until his death. While doing so he poured out a huge assortment of writings which were to establish his reputation as the most learned of all the scholars in the early Church. He completed his monumental translation of the Bible from the Hebrew original while turning out commentaries on Scripture which alone constituted an enormous output—embracing a good number of the books of the Old and New Testaments. In addition, he translated numerous theological works, compiled several encyclopedic type reference works, penned biographies of notable Christian ascetics, and composed an outline history of Christian literature, Famous Men, which became the standard text on the subject. He also kept up a lively correspondence with many of the leading figures of the day and his letters are a major source for the history of his times.

Controversy was the breath of life to Jerome, and even while committed to the supposedly peaceful life of a monk, he plunged into a number of violent quarrels that filled the whole Church with their noise. One of these involved him with his boyhood friend, Rufinus, ruler of the neighboring Latin monastery in Jerusalem. Some preliminary tensions between the two no doubt occurred when Jerome took a high and mighty attitude toward the more relaxed spirit prevalent in Rufinus’s and Melania’s monasteries and when Rufinus complained about Jerome’s audacity in putting out a totally new translation of the Bible. But the issue that led to a lasting break between the two monks was Origenism. Both were longtime admirers of the master; but when a strong anti-Origen movement surfaced in the Church, Jerome went over to the anti-Origen side and accused Rufinus and his bishop, John of Jerusalem, of conniving to spread Origen’s heresies. John in turn excommunicated Jerome and in 397 even tried to have him removed from his diocese by force. A truce was arranged for a time but the war broke out again when Rufinus, now resident in Rome, put out a translation of Origen’s chef d’oeuvre,First Principles, and covered it with a preface that recalled how Jerome himself had often lavished praise on Origen.

Jerome was appalled by the insinuation that he might in any way be sympathetic to Origen’s heterodoxies and he drove his pen furiously into action. The two former friends now blasted each other in pamphlets that sizzled with charge and countercharge. Rufinus finally called it quits and ceased referring to Jerome in his writings, but Jerome was not the type to let up. He continued to level abuse at Rufinus and even when he heard of the man’s death in 411 could not withhold a remark about the “Scorpion Rufinus . . . buried with his brother giants, Enceladus and Porphyrion—that multiple-headed Hydra has finally ceased hissing.”36

Jerome also played an unseemly role in the quarrel between the crafty patriarch of Alexandria, Theophilus (d. 412) and the saintly patriarch of Constantinople, John, later known as Chrysostom (“Golden-tongued”) (d. 407), who was renowned for his eloquence and mastery of Scripture. The unscrupulous Theophilus exploited Jerome’s anti-Origen feelings and secured his assistance in his maneuvers to humiliate Alexandria’s rival see of Constantinople by having its intransigent bishop deposed. John had already alienated a good segment of the populace, including the clergy, and the Empress Eudoxia by his outspoken denunciation of vice and was found guilty of Origenism and other charges at a farcical trial at the Synod of the Oak (403) presided over by Theophilus. John was sent into exile but was soon recalled. However, he soon fell afoul of Eudoxia again and his enemies secured his banishment to Pontus, where he was finally deliberately killed by enforced traveling on foot in wretched weather.

Jerome’s quarrelsomeness and touchiness is also apparent in his correspondence with Augustine, the great African theologian and, later, like Jerome, a doctor of the Church. It began when the younger scholar—eager to make friends with the erudite Hebraist—wrote to Jerome for some advice on theological matters. He also had the temerity to differ with some of Jerome’s biblical opinions and even worse to question the propriety of Jerome’s great project—the translation of the Bible from the Hebrew original. Like so many of his contemporaries, Augustine thought that the authority of the Old Latin version should not be challenged since it was based on the Greek Septuagint, which was generally considered a divinely inspired translation. Moreover, it was consecrated by such long usage in the life and prayer of the Church that Augustine felt that any attempt to change it would seriously disturb the faithful. Jerome was quite irritated by what he thought was the younger man’s brashness and accused him of trying to make a reputation for himself by challenging a well-known and established figure like himself. The two only slowly reached an understanding, in part because of confusion caused by mix-ups in the mail, with later letters arriving before earlier ones. But in the long run Augustine managed to disarm the irascible old Biblicist by masterful diplomacy and tact. He begged the older man’s forgiveness, paid tribute to his unrivaled scriptural expertise, and asked only to be allowed to sit at his feet and learn from him. Jerome was deeply touched and responded with profuse words of affection and esteem for Augustine.

An interesting glimpse into the evolving piety of the Church of Jerome’s day is provided by his pamphlet Against Vigilantius, in which he defends the increasingly popular custom of venerating relics of the martyrs and saints, of burning candles at their shrines, of seeking their intercession in prayer as well as the observance of vigils at the site of their burial. He nicknames his opponent “Dormitianus” (sleepyhead) and mingles serious scholarly arguments with scurrilous invective, which he hurls at his opponent’s head. The pamphlet was widely read and made an important contribution to the general acceptance of these practices by the Church.

The last controversy Jerome took up had to do with the campaign waged by Pelagius, a British theologian and monk in favor of his views on grace, free will, and original sin. Like his colleague Augustine, Jerome was deeply disturbed by Pelagius’ seeming denial of the crippling effects of original sin on our free will and by his denial of our need for divine help in avoiding sin and by his insistence that we could earn our salvation by our own efforts. Jerome and Augustine joined forces to combat Pelagius and their letters at this juncture show them now enjoying a warm friendship. The old monk of Bethlehem was now quite ready to defer to the brilliant bishop of Hippo, whose learning and orthodoxy he had come to fully respect and admire.

Jerome’s declining years were darkened by the terrible series of events that betokened the end of the Roman Empire. On all sides, hordes of barbarians broke through the defenses and spread havoc with fire and sword. Picts, Scots, and Saxons overran Britain; Franks, Burgundians, Alemanni, Huns, Visigoths, and Vandals ravaged Gaul; Suevi, Vandals, and Visigoths, Spain; Vandals, Africa; Ostrogoths, Italy. Then Alaric and his Ostrogoths took the capital itself and pillaged Rome for three days. Jerome was numb with horror at the news: “The lamp of the world is extinguished, and it is the whole world which has perished in the ruins of this one city.”37

Violence struck at Bethlehem too. In 416 Jerome was forced to flee for his life when his own monastery was seized by a band of ruffians—perhaps fanatical devotees of Pelagius—and burned to the ground. But his greatest sorrow was the death of the two people who meant the most to him. In 404 his dearest friend and coworker, Paula, died and left Jerome utterly prostrate with grief. And only a year before his own death in 420 Paula’s daughter Eustochium, whom Jerome also loved beyond measure, fell ill and died—a blow that completely shattered him. The circumstances of his own death a year later are unknown. We only know that he was buried close to the tombs of Paula and Eustochium in their beloved Church of the Nativity a few yards away from the spot held sacred to Christ’s birth.

In the memory of succeeding ages, Jerome’s stature continued to grow until he was finally recognized as a Doctor and Father of the Church in view of the enormous contribution made by his translation of the Bible and his commentaries, by his multifaceted theological and historical writings, by his great influence on the development of Catholic mariology and spirituality, and by the impetus he gave to Western monasticism. The dark side of his personality—his ferocious intolerance and bigotry, his nasty explosions of temper, his uncouth displays of vanity, his delight in putting down his enemies by fair means or foul—was somehow glossed over; and posterity even accorded him the title “saint”—rightly perhaps, for at least no one could deny the burning sincerity and steadfast devotion he manifested in carrying out his commitment to Christ.